ABSTRACT

The context for this paper is a shift in the way citizens engage in democratic processes which has received increasing attention in the literature. Building on previously conducted research, this paper contributes to the conceptualisation of citizenship activities in terms of young people below the voting age from rural communities. Based on reviewing current research, seven emerging contexts that can assist with exploring young people’s citizenship activities are proposed, namely unofficial, individual, glocal, sporadic, online, issues-based, and justice-oriented. These contexts were translated into a framework which is introduced and explored in this paper. To explore this framework, focus groups (n = 26) and a qualitative questionnaire (n = 106) were conducted with young people aged 13–16 from a secondary school in Germany. The proposed framework extends previous conceptualisations of emerging citizenship contexts by looking beyond citizen types and taxonomies to explore the spaces, modes, goals, and the frequency of participants’ citizenship activities. Results indicate that the proposed framework was useful in exploring multiple emerging citizenship contexts. Focus group and questionnaire participants were particularly engaged in glocal, unofficial, sporadic, and issues-based contexts and to a lower degree in individual, online, and justice-oriented contexts. A key challenge is achieving conceptual clarity around the seven contexts.

Introduction

The literature points towards a shift in citizens’ participation and an expansion of citizens’ participation repertoire (Flinders, Wood, and Corbett Citation2020; Norris Citation2004). This shift is, for example, attributed to societal processes such as globalisation, global migration, digitalisation, and individualisation, a shift from a materialist to a postmaterialist society, and anti-politics, a trend which causes the citizenry to distrust traditional political processes (Flinders, Wood, and Corbett Citation2020; Inglehart and Catterberg Citation2002). The expansion of citizens’ participation repertoire, referred to as emerging citizenship contexts in this paper, has received increasing attention in recent years, in terms of citizens in general (Bang Citation2005; Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012; Theocharis and van Deth Citation2018) and younger citizens (Amnå and Ekman Citation2014; Gaiser et al. Citation2016; Pickard Citation2019).

Building on previously conducted research, this paper contributes to the conceptualisation of young people’s emerging citizenship contexts, through proposing a new framework and exploring it with original empirical data. The focus of this paper is on young people below the voting age, who are particularly prone to participating in emerging citizenship contexts (Gaiser et al. Citation2016; Inglehart and Catterberg Citation2002). This might be explained by their exclusion from some traditional venues for participation such as voting, party membership and some community leadership roles, and their access to and uptake of unique and emerging participation online, unofficially, at schools, in youth community organisations and through youth leadership roles. Young people’s exclusion from these traditional venues and their participation in emerging citizenship contexts is an important issue to study because traditional participation still exercises high influence on political decisions in many democratic systems which could marginalise young people in political processes (Bennett Citation2008; Sloam Citation2014). This is particularly problematic because young people are increasingly affected by substantial issues such as the Covid pandemic, climate change and migration without access to the full repertoire of political processes available to adults.

This paper contributes in two ways. Firstly, it extends previously developed frameworks explaining young people’s participation in emerging citizenship contexts. It offers a different approach than citizen typologies (Amnå and Ekman Citation2014; Bang Citation2005; Bennett Citation2008; Westheimer and Kahne Citation2004) by focusing on citizenship activities rather than types of citizens. I argue that citizens, and particularly young people who are in a developmental phase due to the transition from childhood to adulthood, might not be described with one citizen type but rather explore different citizenship activities. Moreover, this research extends taxonomies (Ekman and Amnå Citation2012; Miranda, Castillo, and Sandoval-Hernandez Citation2020; Theocharis and van Deth Citation2018) by looking beyond the type of activities at their modes, spaces, goals, and frequency, to understand their nature in more detail. Secondly, this research extends empirical data on young people’s emerging citizenship contexts by focusing on young people below the voting age in their unique spaces including school, community clubs and peer groups, which is, apart from a few studies (see for example Dunlop et al. Citation2021; Miranda, Castillo, and Sandoval-Hernandez Citation2020; Weller Citation2009) still an under researched field. Furthermore, this research extends empirical data on young people in rural communities which is a unique space for participation and is less researched particularly in relation to young people’s activism, than urban communities (Simonson et al. Citation2022). According to the literature, community service such as the voluntary fire brigade and volunteering within community clubs are important pillars of many rural communities in Germany and thus have a higher uptake there (Gensicke Citation2014; Kleiner and Klärner Citation2019). Justice-oriented causes such as protests, conversely, are taken up less in rural communities because they predominantly happen in urban spaces and are difficult to access, particularly for rural youth without access to a car (Gensicke Citation2014; Kleiner and Klärner Citation2019).

As follows, findings from previously conducted research on young people’s emerging citizenship contexts are outlined. It should be acknowledged that the way citizens participate in democratic systems is complex and the contributions summarised here, are to be perceived as emerging developments rather than lived realities for all citizens alike. Differences in the way the suggested emerging citizenship contexts are relevant to individual citizens, may be related to factors including geographic location and socio-economic background (Henn, Sloam, and Nunes Citation2021; Gaventa and Martorano Citation2016; Kleiner and Klärner Citation2019).

Emerging citizenship contexts proposed in the literature

The literature points to a diversification of citizenship activities in democratic societies in relation to young people, outlined as follows in terms of seven emerging citizenship contexts. The summary focuses on the spaces, modes, goals, and frequencies of citizenship activities. The literature, firstly, points to a move from national citizenship to global citizenship, driven by challenges affecting more than one nation, such as migration or climate change as well as through the ‘immediacy of the media coverage [encouraging] citizens to feel implicated in some way in the lives of those whose story is being told’ (Osler and Starkey Citation2005, 7). This concept is referred to as cosmopolitan citizenship (Osler and Starkey Citation2005) or glocal citizenship which is an adaption of the concept, suggesting that citizens are interested in global issues but participate on a local level (Bang Citation2005; Terren and Soler-I-Martí Citation2021).

Secondly, research suggests increased online participation in loose, digitally enabled social movements, described for example, as connective action (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012). The authors suggest that this type of online participation enables citizens to directly participate in issues of personal relevance without having to adjust their ideals to be part of a collective purpose. Accessing political information is a particularly important aspect of young people’s online citizenship activities (Albert et al. Citation2019).

Thirdly, young people increasingly participate in unofficial citizenship contexts operating outside of established institutionalised politics (Bennett Citation2008; Li and Marsh Citation2008; Pickard Citation2019). This shift is, for example, evident in Pickard’s concept of do-it-ourselves politics, defined as ‘entrepreneurial political participation that operates outside traditional political institutions through political initiatives and lifestyle choices, in relation to ethical, moral, social and environmental themes with young citizens being at the forefront of such actions’ (Citation2019, 390). An increased uptake of unofficial citizenship activities by young people is also discussed by Bennett (Citation2008) who suggests a shift towards actualising citizens who prefer to engage in personally defined activities including selective consumerism and global activism. This shift towards unofficial citizenship activities is connected to young people’s disengagement from official citizenship activities which is termed passive anti-politics by Flinders, Wood, and Corbett (Citation2020) resulting from distrust in politicians and political parties.

Fourthly, literature suggests a move towards more individual citizenship activities. This is described, on the one hand, as participation by individuals through lifestyle activities such as selective consumerism (Stolle, Hooghe, and Micheletti Citation2005) as opposed to participation within organised groups such as during protests. On the other hand, it is described as participation in loose social networks where individuals can express their concerns directly without formally joining a campaign with centralised leadership and are able to drop in and out (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012). Kyroglou and Henn (Citation2021), in addition, suggest there is a collective dimension to individual citizenship activities as they often address collective issues such as climate change.

Fifthly, young people increasingly participate in issues-based citizenship activities (McMahon et al. Citation2018; Norris Citation2004; Pickard Citation2019). This shift is, for example, discussed by Bennett, with his concept of actualising citizens, who ‘are more inclined to become interested in personally meaningful, lifestyle-related political issues rather than party or ideological programs’ (Citation2008, 20). Similarly, Norris suggests that young people in Europe ‘are more likely than their parents and grandparents to engage in cause-oriented political action’ (Citation2004, 16) which the author indicates may be part of a generational shift.

Sixthly, literature points to an increase in justice-oriented citizenship activities that initiate or demand systematic change individually or as part of a collective (Westheimer and Kahne Citation2004). Justice-oriented citizenship activities are also referred to as activist citizenship activities in the literature, which is a term I decided not to use in this article because of its frequent usage in English-speaking literature and negative stereotypes associated with it (Kennelly Citation2011). An increase in justice-oriented citizenship activities, carried out by young people, is particularly reported in terms of (re)claiming urban spaces and in relation to environmental issues (Lam-Knott Citation2020; McMahon et al. Citation2018; Pickard Citation2019).

Finally, literature indicates an increase in citizenship activities that are sporadic as opposed to activities happening at regular intervals (Amnå and Ekman Citation2014; Bang Citation2005; Li and Marsh Citation2008). Concepts put forward by the literature to support sporadic participation, include Amnå and Ekman’s (Citation2014) standby citizens and Bang’s (Citation2005) everyday makers who get engaged part time and when issues arise. Both types of citizens were frequent among samples of young people in Sweden and Britain (Amnå and Ekman Citation2014; Li and Marsh Citation2008). As follows, the approach for defining and identifying citizenship activities in empirical data is detailed, followed by a summary of the proposed framework. Then the methods for data collection and analysis are outlined, followed by a summary of the results and a discussion.

Defining citizenship activities

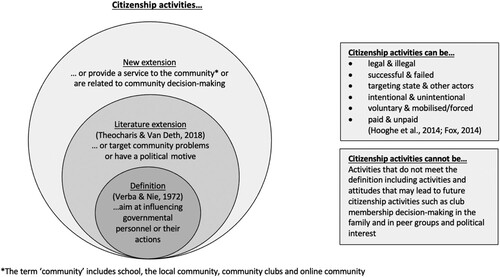

In line with research criticising narrow conceptions of citizenship activities, which are imposed on participants in many empirical studies (Fox Citation2014; O’Toole, Marsh, and Jones Citation2003; Pickard Citation2019), I decided to use a broad definition of citizenship activities. While narrow definitions of citizenship activities often exclusively focus on electoral participation, wider definitions also look at unofficial citizenship activities such as community volunteering. Looking beyond electoral participation is particularly important when exploring young people’s citizenship activities because they are often excluded from electoral participation such as German general elections which are only accessible for young people aged 18 and over. Citizenship activities, as proposed in this paper, aim at influencing governmental personnel or their actions, target community problems, have a political motive, provide a service to the community, or are related to community decision-making (Theocharis and van Deth Citation2018; Verba and Nie Citation1972). I developed this definition for research with young people from rural communities and in school contexts by including spaces relevant to young people in rural communities such as school participation, community service and participation in community clubs (Kleiner and Klärner Citation2019; Müthing, Razakowski, and Gottschling Citation2018). I developed this definition iteratively through reviewing literature and refining the definition through analysing empirical data, reported in the results section of this paper. The proposed definition of citizenship activities is displayed in .

As evident in the Venn diagram in , the proposed definition of citizenship activities is built on a seminal definition by Verba and Nie (Citation1972) including an extension by Theocharis and van Deth (Citation2018). I extended these definitions further by adding ‘provide a service to the community’ and ‘community decision-making’. While the former is to some extent already included in Theocharis and van Deth’s (Citation2018) extension, I argue that there must be a focus on community events that do not directly address community problems. This includes citizenship activities such as volunteering for a community youth event which does not fit the community-problem definition. The latter extension, on community decision-making, includes citizenship activities such as deciding on community club equipment. As evident in , community includes the school, the local community, community clubs and online communities. This wide definition of community is important if research is done with young people below the age of 18 because they are excluded from many official community spaces such as having a seat in the local council and have access to unique spaces such as schools.

I decided to allow a wide range of characteristics in the definition of citizenship activities (see top-right grey box in ). The reason for including these six characteristics is, firstly, that people’s motivations behind engaging in citizenship activities and the outcomes of citizenship activities are often multifaceted. It, thus, is impossible to determine whether participants’ answers represent all or one of multiple reasons for engaging in a citizenship activity, whether they truthfully reflect their decision-making behind an activity or whether they are able to verbalise them at all (Hooghe, Hosch-Dayican, and van Deth Citation2014). Secondly, some of the six characteristics, such as mobilised and targeting other actors, frequently appeared in my empirical data. Thus, excluding them, could have led to an underrepresentation of participants’ citizenship activities.

I decided to exclude some activities and attitudes from the proposed definition of citizenship activities (see bottom-right grey box in ), such as being a member in a community club, because they did not fit my definition of citizenship activities. It should be acknowledged that participants often described these activities as an entry way into citizenship activities. Participants who were in a community club, for example, described being asked by their coach to train younger club members. While I mainly used the Venn diagram to make decisions on what is a citizenship activity in this research, the grey boxes helped to communicate the wide range of characteristics that citizenship activities in this research can have, thus, achieving conceptual transparency. As follows, the proposed framework to explore young people’s emerging citizenship contexts, is introduced.

Exploring emerging citizenship contexts – developing a framework

I developed a framework, displayed in , to identify emerging citizenship contexts, contrast them from traditional citizenship contexts, and identify them in empirical data sets. The framework was developed by creating an initial model based on the literature, which was then developed into a framework through analysing focus group and questionnaire responses, reported in the results section of this article. The framework consists of seven emerging and seven traditional citizenship contexts. Each context is to be seen on either end of a continuum, displayed using double arrows, from traditional to emerging contexts. Given there is enough information, a citizenship activity can be characterised by each of the seven continua depending on its newness or traditionality. The contexts were selected based on reviewing current theories and empirical research on young people’s emerging citizenship contexts, as outlined in the introduction of this article. The literature search focused on post 2010, Germany, Europe, and other Western democracies because of the vast amount of available literature. I assumed that recent literature would provide references to previously conducted research and key contributions from other regions, which were also reviewed where appropriate. All initial emerging and traditional contexts were retained after analysing data. However, I changed some context names to better reflect what they include such as unofficial which was previously called private, and justice-oriented which was previously called activist. In addition, I added a detailed operationalisation of each context to allow for consistent and transparent data analysis. Operationalisations helped to draw a line between emerging and traditional contexts, so I could make decisions on which emerging or traditional contexts characterised each citizenship activity. Operationalisations are displayed in , below each context.

Table 1. Proposed framework of emerging and traditional citizenship contexts.

The following premises underpin the framework. Firstly, a citizenship activity may be described with only emerging, only traditional, or some emerging and some traditional contexts. A citizenship activity cannot, however, be described with an emerging and traditional context from the same continua. It is acknowledged that the lines between the contexts are blurred, meaning an activity might be, for example, online and offline at the same time. To make the framework specific and practically applicable, I decided to not permit overlap within one continuum. Secondly, the framework was developed for use with qualitative data sets as detailed information on each citizenship activity is required to make decisions about assigning different contexts. When collecting data to use with this framework, detailed information on the spaces and modes, goals, and frequency of citizenship activities are needed. Finally, to achieve consistency, decisions on assigning contexts to citizenship activities should be recorded and guide future decisions.

The proposed framework is a model aiming to gain in-depth understanding of a range of emerging citizenship contexts rather than represents the lived realities of all citizens alike. Furthermore, some contexts, labelled as ‘emerging’ in the framework may have existed for a long time, such as justice-oriented activities, and some traditional contexts may characterise current citizenship activities such as the Fridays for Future protests being collective. Thus, when applying the framework with empirical data, the goal is not to judge whether a citizenship activity is mainly emerging or traditional but rather to identify and further examine emerging citizenship contexts. For more information on how I applied the framework, refer to the next section on methods.

Methods

The empirical data shared in this paper, are from a wider research project using a mixed methods case study approach to examine Year 8–10 students’ citizenship activities in Germany. Two data collection methods were selected for this paper, namely focus groups and a qualitative questionnaire. Both methods allowed the collection of in-depth qualitative data and using them together allowed the combination of their unique strengths. Focus groups allowed follow-up questions and participants to discuss as a group, sparking-off each other’s comments. The questionnaire allowed collecting data from more participants as well as collecting detailed background information. All data were collected at AnderbergFootnote1 middle school, a rural secondary school in the German county of Baden-Wuerttemberg. As follows, data collection and analysis methods, the research context, participants and ethical considerations are described. Focus group and questionnaire questions are attached in the supplementary material.

Focus groups

Between June and December 2020, one face to face and seven online focus groups, with 26 students (15 female and 11 male) were conducted at Anderberg middle school. At the time of the focus groups, participants attended Year 8–10 and were aged 13–16.Footnote2 I used staggered recruitment for focus group participants to include participants from different years, form classesFootnote3 and genders. According to the literature, age and gender can influence the uptake of citizenship activities and I, thus, aimed to avoid overrepresentation of participants with one of these factors (Albert et al. Citation2019; Jugert et al. Citation2011). Additionally, I decided to include participants from a range of form classes to gain insights into how students are included in citizenship activities in different form classes. Focus group conversations were designed with a four-step process of questioning. Firstly, I asked participants an open question about their citizenship activities, followed by a group discussion with follow-up questions about the activities. Secondly, I asked participants about specific citizenship contexts which were based on the proposed emerging and traditional citizenship contexts. Contexts at school included school decisions, form class decisions, extracurriculars, activism, and volunteering. Contexts beyond school included community, private contexts, political parties, art and music, and activism. Thirdly, I asked participants to complete a poll in which they chose from a list of citizenship activities. Finally, there was a follow-up discussion about the activities in the poll and participants’ experiences with these activities. Only qualitative focus group data are reported in this paper.

Questionnaire

An online questionnaire was conducted in May 2021 with 115 participants from the same school. A total of 106 valid responses were used in the analysis. I recruited roughly the same number of questionnaire participants from Year 8, 9 and 10 from a total of eight form classes I distributed the questionnaires as an in-class activity or as a homework task. Since participation was voluntary, students could choose between a worksheet and the questionnaire. Conducting the questionnaire during class time and as a homework task, encouraged participation since students were not asked to offer their free time. A total of 21 questionnaire participants also participated in focus group conversations. Due to the overlap between participants and the gap in participant numbers, focus group and questionnaire results are presented individually when focusing on frequency in the results section. The questionnaire sample overrepresents participants from rural villages (61%), with medium to high perceived socio-economic backgrounds (78%), and low perceived political interest (72%) (see ). Participants predominantly live in villages and small towns in successful rural regions, characterised by high incomes, high tax revenues, low percentages of early school leavers, good broadband coverage, and lacking access to public transportation (Sixtus et al. Citation2019). Perceived socio-economic status was measured by asking participants to place their families on a ladder with 10 being the people who are best off, and 1, the people who are the worst off.

Table 2. Profile of questionnaire participants.

In the questionnaire I used a four-step question process. Firstly, I asked participants to answer a Likert scale question on whether they participated in citizenship activities almost always, often, seldom, or never, at and beyond school during the past 2 years. Secondly, those participants answering with almost always, often, or seldom were asked to describe the citizenship activities they participated in. Thirdly, participants completed a Likert scale question with a range of citizenship activities at and beyond school. Finally, participants described their experience of participating in citizenship activities. Only data from qualitative responses are reported in this paper.

Data analysis

All focus group data were transcribed and, together with qualitative questionnaire data, uploaded to NVivo and analysed in the following way. Firstly, I coded all data related to citizenship activities. During this step, I used the proposed definition of citizenship activities (see ) to decide which activities to include in the analysis. To create transparency and consistency across participants and data collection instruments, I recorded evidence of the coding and decision-making process.

Secondly, I assigned a code to all citizenship activities in form of the seven emerging and seven traditional citizenship contexts, using the definitions from the proposed framework and an Excel table (see ).

Table 3. Coding excerpt from focus group data.

To assign emerging and traditional citizenship contexts, I looked at each code and related participant comments and assigned either the number 1 if they were characterised by this context or the number 0 if they were not characterised by this context. After the initial coding process, I adjusted the numbers to represent the frequency of each code. Some codes included participant statements that lacked information which meant they could not be assigned all contexts. I used the data from assigning contexts to compare the frequency of participants’ uptake of the seven emerging and traditional contexts. Comparing the frequency of uptake of each citizenship context, based on qualitative data, can be considered problematic. This is because questionnaire and focus group data do not necessarily provide information on each participant’s uptake of the seven contexts but rather on the citizenship contexts that participants talked about. However, by using different data collection instruments, different question types and follow-up questions, I assumed that participants at least shared the most relevant of their citizenship contexts.

Finally, after assigning the emerging and traditional contexts to the codes, I examined each of the seven contexts. I did this by conducting thematic analysis on all participant comments for each context in NVivo, using some strategies outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2022), including active and critical reading, note-taking, comprehensive coding, and creating patterns through categorising and connecting codes using mind maps. The themes, reported in this article, focus on further explaining the seven emerging citizenship contexts, particularly in relation to their spaces, modes, frequencies, and goals.

Ethical considerations, translation, and reliability

As follows ethical considerations, the process of translation and the reliability of this research will be discussed. All participants, as well as legal guardians of participants below the age of eighteen, gave informed consent to participate. Consent was also gained from school leadership and form teachers to allow me to contact their students. Ethical approval was granted by the University’s Education Ethics Committee.

All data were collected in German because this is my native language and the native language of most participants. I analysed all participant data in German and assigned English codes on NVivo. I decided to create English codes because the main research outputs will be in English. Creating codes in English and the translation process involved in this, helped me to further understand participants’ comments because I considered the meaning of individual words and expressions through translation. For the participant quotes included in this article, I removed filler words, pauses, repetitions and hesitation sounds, indicated through ellipses, to achieve readability. Each translated quote included in this article, was discussed (and modified if necessary) with a German speaking, native British teacher to add reliability to translated quotes.

Research exploring ambiguous concepts such as citizenship contexts requires careful consideration to make results reliable (Kennelly Citation2011; Sveningsson Citation2016). To increase conceptual reliability, I defined key concept, made them transparent (see and ), and highlighted issues with using key concepts throughout the discussion section. Furthermore, I used accessible language during focus groups and the questionnaire. Instead of using ambiguous terms like ‘justice-oriented’ for example, I asked participants whether they changed something they were unhappy with. Furthermore, I provided definitions of key concepts to participants during focus groups and the questionnaire and used follow-up questions (see supplementary material).

Participants’ uptake of citizenship activities was influenced by social distancing measures and school lockdowns, caused by the Covid pandemic. To examine and make these differences transparent, I asked questionnaire participants about their citizenship activities in the past two years to also include participation before the pandemic. In the results section, citizenship activities that participants did before and during the pandemic are reported. I also asked participants whether and how the pandemic affected their citizenship activities. Results suggest that the pandemic affected participants differently with differences in terms of individual participants and citizenship activities. Less than half of the participants reported a decrease in their citizenship activities at school (17%) and beyond school (40%) during the pandemic. A few participants suggested that they engaged in more citizenship activities because more issues came up (6%), they were more interested in politics (5%), and they increased their online participation due to social distancing requirements (4%) during the pandemic. More than a quarter of questionnaire participants suggested that the pandemic has not affected their citizenship activities at school (26%) and beyond school (32%).

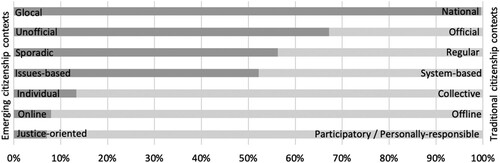

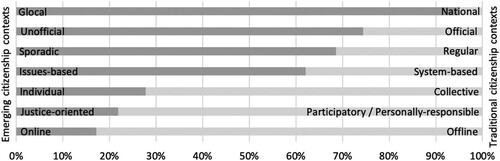

Results – participants’ engagement in emerging and traditional citizenship contexts

In this section, I summarise results on participants’ engagement in the proposed emerging citizenship contexts. This is followed by a discussion of the results, relating them to existing literature, in the next section. and show the relative number of questionnaire and focus group participants who were involved in each of the proposed emerging and traditional contexts. The data are based on assigning the seven emerging and traditional contexts to all citizenship activities discussed in focus groups and the questionnaire.

Results show that participants’ citizenship activities were characterised by all proposed emerging contexts but to varying degrees. While there was more participation in glocal, unofficial, sporadic and issues-based contexts, participants engaged less in individual, online and justice-oriented contexts. As follows, participants’ engagement in glocal, unofficial, sporadic, and issues-based contexts will be summarised by reporting themes. I decided to focus on the four emerging contexts that were most meaningful to the participants in this study. Results from participants' engagement in individual, justice-oriented and online citizenship contexts, instead, will be summarised and related to the literature in the discussion section. The themes reported in this section focus on the description of emerging citizenship contexts, particularly regarding their modes, spaces, frequencies, and goals. Some themes are summarised in tables along with participant comments while others are reported in-text. As described in the methods section of this paper, I developed the themes through in-depth thematic analysis of focus group and questionnaire data while percentages reflect participants' uptake of the citizenship contexts.

Glocal citizenship contexts

The glocal context includes all citizenship activities that address local or global issues and/or are carried out at a local or global level. There was a high percentage of glocal citizenship contexts in the questionnaire (99%) and focus groups (84%). Participants discussed the glocal citizenship context through a combination of issues and citizenship activities at their school, their local communities, and their global communities, as illustrated in .

Table 4. Excerpts from data on glocal citizenship contexts.

Findings suggest that there were overlaps between school, local community, and global means to address issues. This is evident in the example of buying a fair-trade product which could be a local activity since it happens in the local supermarket. It could also be considered global, however, since fair-trade is a global label and impacts people who live around the world. Thus, results suggest that glocal is a particularly useful label for citizenship contexts that are increasingly intertwined.

Unofficial citizenship context

Citizenship activities labelled unofficial are not directly supported, driven, or invited by the state. Findings indicate that more participants discussed unofficial contexts in the qualitative questionnaire (67%) and focus groups (75%) than official contexts. Furthermore, a total of 42% of questionnaire and 31% focus group participants were exclusively engaged in unofficial citizenship contexts, as opposed to collective or a combination of unofficial and collective citizenship contexts. Findings suggest that participants were engaged in unofficial citizenship contexts in a wide range of spaces including their form classes, extracurriculars, community clubs, churches, social media, and familiar spaces such as the supermarket, as illustrated in .

Table 5. Data excerpts on unofficial citizenship spaces.

As evident in Lotta’s comment in , unofficial citizenship contexts were sometimes described as a combination of engaging in hobbies, and learning skills, with service such as offering up one’s time to raise money at a charity concert. Participants’ citizenship activities labelled unofficial, included helping at school and in the community, accessing and discussing political information, engaging in justice-oriented causes, and making unofficial decisions such as choosing equipment for their sports club. Participants’ citizenship activities labelled official, instead, included decision-making in the student council, participation in service organisations and formal community decision-making.

Sporadic citizenship contexts

Citizenship activities labelled sporadic happen at irregular intervals. Findings indicate a high percentage of sporadic citizenship contexts in the questionnaire (56%) and focus groups (69%). Participants discussed sporadic contexts as participating in citizenship activities sometimes, once a year, once and for a while (see ).

Table 6. Excerpts from data on sporadic contexts.

Confirmation, mentioned by Constantin, is a Christian celebration to become an official member of a church community. In participants’ villages, all confirmands (young people aged 14, who decide to take part in the confirmation) undergo several weeks of group training before they attend the confirmation ceremony. This usually involves participating in citizenship activities in the community such as helping the elderly, raising money, and leading church children’s groups. The confirmation period is an example for sporadic participation.

Participants described sporadic engagement in online spaces, where participation was almost exclusively done sporadically. Participants also engaged sporadically in school volunteering and school events while engagement in school extracurriculars and the student council was more likely described as regular. In terms of the community, participants engaged in sporadic community volunteering and decision-making while citizenship activities in community clubs were rather described as regular. Participants also described sporadic engagement in familiar spaces such as the supermarket, their families and peer groups. Furthermore, sporadic engagement was linked with issues-based participation. This is illustrated by Martin’s (Y9) comment, suggesting that his participation ended when the issue was resolved: ‘...We had a teacher with whom the class had a problem. As the class representative, I spoke to the teacher and also our form teacher and now it's better.’ There were only few citizenship activities carried out always, including consumer choices such as being vegan.

Issues-based citizenship contexts

Citizenship activities labelled issues-based focus on issues or events as opposed to membership in organisations. Many participants in my research took part in issues-based contexts with a total of 52% of questionnaire and 62% of focus group citizenship activities labelled issues-based. Participants were interested in a heterogenous range of issues including the environment, human and animal rights, children and elderly, community and school resources, school issues and political and social topics (see ). System-based citizenship contexts, conversely, were related to being a member in extracurricular and community clubs or having a service role, such as being a student first aid officer.

Table 7. Excerpts from questionnaire and focus group data on issues-based context.

As previously mentioned, issues-based contexts were related to sporadic engagement with participation ending when issues were perceived to be resolved. Many issues-based contexts focussed on glocal issues, thus, suggesting overlap between glocal and issues-based contexts.

Discussion

As follows, key findings in relation to the seven emerging citizenship contexts are discussed and related to the literature. Firstly, most of participants’ citizenship activities were labelled glocal. This result aligns with Osler and Starkey's (Citation2005) concept of the cosmopolitan citizen who is interested in issues affecting more than one nation and engages in a range of local and global contexts to address these issues. A key aspect of my participants’ engagement with global issues focussed on citizenship activities at school which I believe constitutes an extension of the cosmopolitan citizen in terms of school-aged young people. An example for addressing a global issue at school, is my participants’ engagement in the yearly Pink Day at their school which raises awareness for LGBTQ+ rights.

Secondly, results suggest high participation in unofficial citizenship contexts. This is consistent with literature arguing that young people are disengaged from official political processes including party politics and instead engage in unofficial citizenship contexts (Bang Citation2005; Bennett Citation2008; Norris Citation2004; Pickard Citation2019). My data particularly supports the presence of Pickard’s (Citation2019) doing-it-ourselves (DIO) activities. Examples of DIO activities in my data are buying fair-trade products and raising awareness for issues. As opposed to Pickard’s (Citation2019) suggestion of young people being at the forefront of DIO activities, my participants were rather involved as participants than initiators. Further concepts from the literature, namely Bennett's (Citation2008) actualising citizens and Bang’s (Citation2005) everyday makers, who prefer to engage in personally defined activities, were evident in my data. However, most participants in this study could not be classified into a citizen type. Instead, more than half of participants engaged equally in official and unofficial citizenship contexts. Furthermore, exclusive participation in unofficial contexts might not be in the best interest of citizens as citizenship activities labelled official, such as being in the formal student assembly or having a seat in the local youth council, currently still exercise high influence on political decision-making in many democratic systems as opposed to unofficial participation (Bennett Citation2008; Sloam Citation2014).

Thirdly, participants’ citizenship activities were characterised by being sporadic and issues-based. This aligns with Bang’s (Citation2005) everyday makers, Amnå and Ekman’s (Citation2014) standby citizens, and Bennett’s (Citation2008) actualising citizens who were commonly identified among samples of young people from Sweden, the UK and Australia (Amnå and Ekman Citation2014; Bennett Citation2008; Li and Marsh Citation2008). While these typologies suggest that sporadic and issues-based engagement is a characteristic of a type of citizen, my findings indicate that participants engaged in regular and sporadic or issues-based and system-based citizenship contexts. Whether an activity was taken up sporadically or addressed an issue, was more related to the space in which it took place than the participants themselves. Participants’ sporadic participation predominantly took place online, as part of events, through school and community volunteering, and activities within the family or peer group. Regular engagement instead, was related to taking up service roles and formal decision-making processes at school. The importance of issues-based participation in my data, confirms Norris’ (Citation2004) argument that cause-based political engagement is a significant aspect of young people’s political participation. My results also suggest that participants constitute a heterogenous group with an interest in a wide range of issues including global, local, and school concerns. Interestingly, even though participants expressed interest in a wide range of issues, most participants suggested they were hardly or not at all interested in politics (71%). One reason for this might be a narrow conception of what is included in the concept of politics by participants (O’Toole et al. Citation2003; Sveningsson Citation2016).

Fourthly, in line with Bennett and Segerberg’s (Citation2012) concept of connective action and Stolle, Hooghe, and Micheletti's (Citation2005) research on selective consumerism, I identified some (online) participation as part of loose networks and individual action such as raising awareness against online sexism and buying fair-trade products. My findings also support literature on collective and cosmopolitan aspects of individual lifestyle choices (Kyroglou and Henn Citation2021). Even though lifestyle choices were carried out individually, they predominantly addressed collective and cosmopolitan issues such as environmental issues or animal cruelty. The low uptake of online citizenship contexts by participants in this study challenges literature on the significance of online citizenship contexts to young people (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012; Bessant, Farthing, and Watts Citation2016). Instead, my findings suggest that the significance of online contexts depends on individual citizenship activities. Participants in my study particularly discussed accessing political information and online justice-oriented citizenship activities , particularly raising awareness on social media. This finding is in line with literature suggesting the internet plays an important role in young people’s access to political and social issues (Albert et al. Citation2019). The occurrence of individual and online citizenship contexts may be limited in this study due to the focus on schools. Findings indicate that apart from a few, most citizenship activities at school were labelled offline and collective. In addition, the rural context of my study might have decreased individual participation because of the importance of community clubs to my participants which form a key aspect of rural communities and predominantly foster collective participation (Gensicke Citation2014). In terms of online participation, it should be acknowledged that some participants were unsure about the concept of online citizenship activities and might, thus, have omitted some activities because they did not define them as citizenship.

Finally, empirical data indicates low participation in justice-oriented citizenship contexts. This is in line with literature looking at a wide range of contexts of young people’s engagement as citizens (Westheimer and Kahne Citation2004; Wood et al. Citation2018). There is also a growing number of research reporting high uptake of justice-oriented citizenship contexts among young people. These studies, however, often focus on specific young people such as urban populations (Lam-Knott Citation2020; McMahon et al. Citation2018) or specific issues such as environmental protests (Pickard Citation2019). Three factors related to my sample, may have further reduced the presence of the justice-oriented context in this research, namely location, socio-economic background, and conceptual clarity. Firstly, participants in this study live in rural villages which can restrict access to justice-oriented causes. Protests, for example, predominantly happened in urban areas and were difficult to access for participants (Gensicke Citation2014). In addition, some justice-oriented citizenship contexts were regarded less appropriate in rural areas because they are less common such as political graffiti. Secondly, my sample is unique in terms of participants’ high perceived socioeconomic backgrounds. While some research suggests that young people with higher socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to participate in justice-oriented citizenship contexts (Henn, Sloam, and Nunes Citation2021), my findings suggest that participants’ satisfaction with their resources at home and at their school did not create the need to affect change (Gaventa and Martorano Citation2016). Finally, results suggest that participants were unsure about the concept of ‘justice-oriented’ which may have further reduced the presence of justice-oriented citizenship contexts in this research.

Conclusion

In this paper, I proposed a framework that conceptualises seven emerging citizenship contexts and set out to identify and examine them with original empirical data. This framework offered a novel approach to explore young people’s participation by describing overlapping emerging contexts characterising citizenship activities. I suggest that this is more illustrative of young people’s heterogenous experiences than using citizen typologies which did not reflect my participants’ experiences who were often engaged in multiple overlapping emerging and traditional citizenship contexts. The proposed framework worked best with rich qualitative data, collected through focus groups, which allowed for follow-up questions on the modes, spaces, frequencies, and goals of participants’ citizenship activities. Results suggest that clarifying the seven contexts was a challenge of the proposed framework which I addressed by creating detailed operationalisations and carefully selecting words to reflect each context to be as unambiguous for other researchers reading or using the framework. In focus groups and the questionnaire, I also took care to use accessible and unambiguous language for participants.

Future research using the proposed framework, could place even more emphasis on negotiating a shared understanding of the seven contexts during data collection, particularly in terms of online and justice-oriented citizenship contexts. The proposed framework could be used in future work with a representative data set to comment on trends regarding the uptake of the seven contexts, representing a larger number of young people. Future studies using the proposed framework, could also compare participants from different backgrounds, particularly in terms of location and socio-economic background which were, according to the results of this study, connected to the uptake of emerging citizenship contexts.

In terms of the seven emerging contexts, results suggest that glocal, unofficial, sporadic, and issues-based contexts were particularly relevant to participants while the importance of online, individual, and justice-oriented citizenship contexts could be reassessed by future studies, particularly with young people from rural communities and with high socio-economic backgrounds. Results also suggest that many participants were exclusively engaged in unofficial citizenship contexts at school and in their communities which could lead to a marginalisation of their voices as many impactful political decisions are currently still done in official spaces such as in the student council or through elected community leaders. Citizenship education and related school subjects could be spaces where young people are supported to reflect on their power in political decisions within unofficial and official citizenship contexts and gain skills to engage in both official and unofficial contexts to amplify their voices. I argue that, in addition to young people gaining participatory skills, it is crucial that genuine participatory opportunities are created in official citizenship contexts that are welcoming young people’s participation.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (127.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article

Notes

1 Pseudonyms were chosen for participants, the school and villages to protect participants’ identity.

2 Except for two participants who were 17 and 19 years old.

3 At Anderberg middle school, students are grouped in form classes (Klassen) of 20–30 students. With this group students attend most of their subjects. They also have a form teacher assigned to their form class who teaches them in most subjects and oversees their pastoral care.

4 The contexts personally-responsible, participatory and justice-oriented are based on Westheimer and Kahne’s (Citation2004) three types of citizens. In the proposed framework, however, I used them to describe citizenship contexts that characterise citizenship activities rather than types of citizens.

References

- Albert, M., K. Hurrelmann, G. Quenzel, and P. Kantar. 2019. Jugend 2019. Eine Generation meldet sich zu Wort. 18. Shell Jugendstudie [Young people in 2019. A generation speaks up. 18th Shell Youth Study].

- Amnå, E., and J. Ekman. 2014. “Standby Citizens: Diverse Faces of Political Passivity.” European Political Science Review 6 (2): 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1017/S175577391300009X.

- Bang, H. 2005. “Among Everyday Makers and Expert Citizens.” In Remaking Governance: Peoples, Politics and the Public Sphere, edited by J. Newman, 159–178. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Bennett, W. L. 2008. “Changing Citizenship in the Digital Age.” In Civic Life Online: Learning How Digital Media Can Engage Youth, edited by W. L. Bennett, 1–24. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Bennett, W. L., and A. Segerberg. 2012. “The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics.” Information Communication and Society 15 (5): 739–768. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2012.670661.

- Bessant, J., R. Farthing, and R. Watts. 2016. “Co-designing a Civics Curriculum: Young People, Democratic Deficit and Political Renewal in the EU.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 48 (2): 271–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2015.1018329.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2022. Thematic Analysis. A Practical Guide. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Dunlop, L., L. Atkinson, J. E. Stubbs, and M. Turkenburg-Van Diepen. 2021. “The Role of Schools and Teachers in Nurturing and Responding to Climate Crisis Activism.” Children’s Geographies 19 (3): 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2020.1828827.

- Ekman, J., and E. Amnå. 2012. “Political Participation and Civic Engagement: Towards a New Typology.” Human Affairs 22 (3): 283–300. https://doi.org/10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1.

- Flinders, M., M. Wood, and J. Corbett. 2020. “Anti-politics and Democratic Innovations.” In Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance, edited by S. Elstub, and O. Escobar, 148–160. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Fox, S. 2014. “Is it Time to Update the Definition of Political Participation?” Parliamentary Affairs 67 (2): 495–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gss094.

- Gaiser, W., W. Krüger, J. de Rijke, and F. Wächter. 2016. “Jugend und politische Partizipation in Deutschland und Europa [Youth and political participation in Germany and Europe].” In Politische Beteiligung junger Menschen. Grundlagen-Perspektiven-Fallstudien, edited by J. Tremmel, and M. Rutsche, 13–38. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Gaventa, J., and B. Martorano. 2016. “Inequality, Power and Participation – Revisiting the Links.” IDS Bulletin 47 (5): 11–29. https://doi.org/10.19088/1968-2016.164.

- Gensicke, T. 2014. Bürgerschaftliches Engagement in den ländlichen Räumen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland - Strukturen, Chancen und Probleme. [Civic engagement in rural areas in Germany – structures, opportunities and problems.] TNS Infratest Sozialforschung.

- Henn, M., J. Sloam, and A. Nunes. 2021. “Young Cosmopolitans and Environmental Politics: How Postmaterialist Values Inform and Shape Youth Engagement in Environmental Politics.” Journal of Youth Studies 25 (6). https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.1994131.

- Hooghe, M., B. Hosch-Dayican, and J. W. van Deth. 2014. “Conceptualizing Political Participation.” Acta Politica 49: 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.7.

- Inglehart, R., and G. Catterberg. 2002. “Trends in Political Action: The Developmental Trend and the Post-Honeymoon Decline.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 43 (3–5): 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/002071520204300305.

- Jugert, P., P. Noack, K. Diener, and A. Benbow. 2011. “Politische Partizipation und soziales Engagement unter jungen Deutschen, Türken und Spätaussiedlern.” [Political Participation and Social Engagement of young Germans, Turks and German Resettlers]. Politische Psychologie 1 (1): 36–53.

- Kennelly, J. 2011. Citizen Youth. Culture, Activism, and Agency in a Neoliberal Era. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kleiner, T.-M., and A. Klärner. 2019. Bürgerschaftliches Engagement in ländlichen Räumen. Politische Hoffnungen, empirische Befunde und Forschungsbedarf [Voluntary work in rural communities. Political hopes, empirical findings and research needs]. Thünen Working Paper 129.https://literatur.thuenen.de/digbib_extern/dn061365.pdf

- Kyroglou, G., and M. Henn. 2021. “Young Political Consumers Between the Individual and the Collective: Evidence from the UK and Greece.” Journal of Youth Studies 25 (6): 833–853. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.2012139.

- Lam-Knott, S. 2020. “Reclaiming Urban Narratives: Spatial Politics and Storytelling Amongst Hong Kong Youths.” Space and Polity 24 (1): 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2019.1670052.

- Li, Y., and D. Marsh. 2008. “New Forms of Political Participation: Searching for Expert Citizens and Everyday Makers.” British Journal of Political Science 38 (2): 247–272. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000136.

- McMahon, G., B. Percy-Smith, N. Thomas, Z. Bečević, S. Liljeholm Hansson, and T. Forkby. 2018. Young People’s Participation: Learning from Action Research in Eight European Cities.Working paper D5.3. PARTISPACE.

- Miranda, D., J. C. Castillo, and A. Sandoval-Hernandez. 2020. “Young Citizens Participation: Empirical Testing of a Conceptual Model.” Youth and Society 52 (2): 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X17741024.

- Müthing, K., J. Razakowski, and M. Gottschling. 2018. LBS-Kinderbarometer Deutschland 2018. Stimmungen, Trends und Meinungen von Kindern aus Deutschland [LBS-Children Barometer Germany 2018. Spirit, trends and opinions of children from Germany].

- Norris, P. 2004. “Young People & Political Activism: From the Politics of Loyalties to the Politics of Choice?” Paper for the Conference “Civic Engagement in the 21st Century: Toward a Scholarly and Practical Agenda” at the University of Southern California, October 1–2, January 2004.

- Osler, A., and H. Starkey. 2005. Changing Citizenship: Democracy and Inclusion in Education. Maidenhead and New York: Open University Press.

- O’Toole, T., D. Marsh, and S. Jones. 2003. “Political Literacy Cuts Both Ways: The Politics of Non-participation among Young People.” The Political Quarterly 74 (3): 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.00544.

- Pickard, S. 2019. Politics, Protest and Young People: Political Participation and Dissent in the 21st Century Britain. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Simonson, J., N. Kelle, C. Kausmann, and C. Tesch-Römer. 2022. Freiwilliges Engagement in Deutschland - Der Deutsche Freiwilligensurvey 2019. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Sixtus, F., M. Sulpina, S. Sütterlin, J. Amberger, and R. Klingholz. 2019. Teilhabeatlas Deutschland. Ungleichwertige Lebensverhältnisse und wie die Menschen sie wahrnehmen [Participation atlas of Germany. Inequitable living conditions and how people perceive them]. Berlin Institut für Bevölkerung und Entwicklung & Wüstenrot Stiftung. https://www.berlin-institut.org/fileadmin/Redaktion/Publikationen/PDF/BI_TeilhabeatlasDeutschland_2019.pdf.

- Sloam, J. 2014. “New Voice, Less Equal: The Civic and Political Engagement of Young People in the United States and Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (5): 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012453441.

- Stolle, D., M. Hooghe, and M. Micheletti. 2005. “Politics in the Supermarket: Political Consumerism as a Form of Political Participation.” International Political Science Review 26 (3): 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512105053784.

- Sveningsson, M. 2016. ““I Wouldn’t Have What It Takes”: Young Swedes’ Understandings of Political Participation.” Young 24 (2): 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308815603305.

- Terren, L., and R. Soler-I-Martí. 2021. ““Glocal” and Transversal Engagement in Youth Social Movements: A Twitter-Based Case Study of Fridays for Future-Barcelona.” Frontiers in Political Science 3: 635822. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.635822.

- Theocharis, Y., and J. W. van Deth. 2018. “The Continuous Expansion of Citizen Participation: A New Taxonomy.” European Political Science Review 10 (1): 139–163. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755773916000230.

- Verba, S., and N. H. Nie. 1972. Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Weller, S. 2009. “Exploring the Spatiality of Participation: Teenagers’ Experiences in an English Secondary School.” Youth & Policy 101: 15–32.

- Westheimer, J., and J. Kahne. 2004. “What Kind of Citizen? The Politics of Educating for Democracy.” American Educational Research Journal 41 (2): 237–269. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041002237.

- Wood, B. E., R. Taylor, R. Atkins, and M. Johnston. 2018. “Pedagogies for Active Citizenship: Learning Through Affective and Cognitive Domains for Deeper Democratic Engagement.” Teaching and Teacher Education 75: 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.07.007.