ABSTRACT

In India, the past two decades have been crucial for the growing popularity of Electronic Dance Music (EDM). This is largely due to the burgeoning presence and significance of EDM festivals as a performative site of a contemporary Indian youth culture. A salient feature capturing the zeitgeist of twenty-first century, urban, modern Indian youth is EDM’s gradual permeation into the cultural fabric of India through crucial collaborations with cultural industries like Bollywood. It is a truism that the legacy of Goa Trance remains a dominant point of reference in the global imagination of the Indian EDM scene. This article, however, argues that the contemporary mode of Indian Electronic Dance Music Culture (EDMC) has largely developed independently of this legacy. The main proponent of contemporary EDMC in urban India has been the multiple greenfield EDM festivals held annually all over the country. This article draws on fieldwork data collected between 2016-2018 at Indian EDM festival sites. Using this empirical data, the article examines the ‘performance’ of Indian EDMC and considers whether it is viable to speak in terms of an Indian way of raving, as a variation of other ‘local’ ways of performing EDMC that may exist elsewhere in the world.

Introduction

In India, the past two decades have seen the growing popularity of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) and the significance of EDM festivals as a performative site of a contemporary urban Indian youth culture. This becomes evident from national online news articles describing how the music is ‘young India’s poison of choice’ (Kappal Citation2016) with EDM festivals having allegedly induced an ‘electric fever’ (Samarth Citation2015) over the country as EDM beats fuse with the soundscape of Bollywood (Bhat Citation2014), India’s biggest commercial film industry. India has also seen the rise of local EDM artists such as Nucleya, Dualist Inquiry, Sanaya Ardeshir (Sandunes) OX7GEN, and Ritviz who have garnered significant media and music industry attention in the country (Arora Citation2017). EDM and the consequent Electronic Dance Music Culture (EDMC) in India thus becomes a complex, nuanced site of contemporary youth culture enactment.

This article draws on fieldwork data collected between 2016 and 2018 at two Indian EDM festival festivals, Sunburn and Enchanted Valley Carnival (EVC), and post-festival interviews with participants recruited on-site. Using this empirical data, the article examines the ‘performance’ of Indian EDMC and considers whether it is viable to speak in terms of an Indian way of raving, as a variation of other ‘local’ ways of performing Electronic Dance Music Culture (EDMC) that exist elsewhere in the world. In examining questions around an Indian way of raving, the article focuses on critical aspects of Indian EDMC, including who participates in these spaces and where such spaces take form. Our purpose here is to empirically elucidate a basic understanding of Indian EDMC and in doing so argue that one must not try and read Indian EDMC merely as a global youth culture shaping the local spaces and sites of Indian EDM festivals. Instead, it is argued, one must investigate how the local shapes those elements of a global youth culture and music that have transcended their western origins. While research on other musical genres, notably rap and metal, has focused on the importance of local narratives in shaping the trans-local evolution of music genres and their associated cultural scenes (Bennett Citation2000; Harris Citation2000), to date there has been little investigation of this in relation to EDM.

EDM in a global context

Although EDM is typically understood as having emerged during the 1980s, its roots are in the early electronic music experiments of artists including Kraftwerk, Girorgio Moroder and Brian Eno during the 1970s (Barr Citation2013). Such music transgressed the guitar-based styles of much 1970s popular music, something further consolidated by disco in the late 1970s (Lawrence Citation2003) and synth-pop in the early 1980s (Albiez Citation2011). Early styles of EDM included techno, a style influenced by early European electronic music that emerged from Chicago dance clubs and house, the latter evolving from clubs on the Spanish island of Ibiza where local DJs began experimenting with a style of music referred to as balearic beat (also known as balearic house) (Melechi Citation1993). Foreign DJs who performed in these clubs introduced balearic beat into clubs in their home countries, notably in the UK where the city of Manchester quickly became a hub for a house, techno and other styles, such as dubstep, featured at organised dance party events referred to as raves (Haslam Citation2000). In an early study of EDM’s global reach, Laing (Citation1997) highlighted the burgeoning trans-local network of EDM DJs and clubbers. In this context, the Indian province of Goa became particularly important, hosting a series of EDM gatherings that drew on Goa’s hippie counter-cultural past while at the same time fashioning a distinctive brand of EDM parties and festivals that highlighted EDM’s growing status as a trans-locally connected scene. During this global evolution, EDM also adapted to other local environments, creating as it did specific localised enactments of EDMC such as the Australian ‘bush doof’, so called because of the locating of EDM parties featuring repetitive beats (given the onomatopoeic name ‘doof’) in natural ‘bush’ settings (Luckman Citation2003).

Identity and community in EDM

If EDM has had a significant impact on the music and youth cultural landscapes of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, it has been equally impactful on ways of theorising the cultural significance of music and its influence on notions of identity and community. During the early 1990s, Redhead (Citation1993) argued that EDM gatherings indicated a withering of subcultural segmentation of youth as clubbers from an apparently diverse array of backgrounds were united on the dance floor. Melechi (Citation1993) invoked the postmodern turn to conceptualise raving as a form of hedonistic escapism, whereby individuals could loose themselves in the experience of the rave and thus achieve a temporary escape from the expectations and routines placed on them in their regular everyday lives. This interpretation of EDM as a place of temporal gatherings where new identities could be fashioned and bonds formed was developed by Bennett (Citation1999) and Malbon (Citation1999) through their application of Maffesoli’s (Citation1996) concept of neo-tribes to EDMC. For Maffesoli, the combined effects of risk and individualisation in contemporary society have led individuals to seek out new forms of social attachment that centre around temporal bonds achieved, for example, through attending sporting events and participating in shopping and other consumption rituals, such as restaurant and café culture. Bennett and Malbon’s respective studies extended neo-tribes to EDM, emphasising the temporal, yet intense, nature of the collective participation in EDM events. The ethnographic data collected by Bennett and Malbon supported to some degree earlier interpretations of EDM as providing a means of escape for participants, but rather than reducing this to an individual endeavour, Bennett and Malbon considered the neo-tribal bonds that emerged within the EDM scene as allowing for collective forms of transgression and escape. As in the case of Redhead’s interpretation of EDM, Bennett and Malbon also considered it to be an inherently post-subcultural (Muggleton Citation2000) manifestation of youth identity. St. John maps similar trends in EDM through applying the idea of communitas to EDM gatherings, arguing that this denotes a desire for ‘social warmth howsoever temporary, perceived to have been lost or forgotten in the contemporary world of separation, privatisation and isolation’ (Citation2009, 38–39).

Similar traits can be seen in the appeal of EDM participation in India, albeit with its own localised rituals and collectively shared understandings of escape and transgression. To explore this, we apply the concept of rasa. Deeply rooted in ancient traditions of the subcontinent of India, Rasa, was presented in Natyasastra, a treatise of drama, penned by an ancient Sanskrit author Bharata in 500 BCE. The ancient Indian dramaturgical treatise Natyasastra laid out an art reception theory of Rasa that spoke to the emotional audience responses to sensory inputs like dance, drama and music performances (Pollock Citation2016). The artist emotes through their performance whilst being in the state of bhava (emotion) and allowing the audience to transcend to the state of anubhava (experience) which then results in the co-creation the rasa. Rasa thus, talks of a collective transformative experience generated through an exchange between performer and spectator (Rangacharya Citation2014). It is in this way, we argue, that the rasa theory has shared linkages with ideas of liminality and communitas within the manifestation of EDMC performances while illustrating the localised sensibilities of Indian EDMC. The rasa theory, thus, makes for an effective cultural code to understand how the spaces of play like the Indian EDM festival sites shape the contemporary urban youth cultures around their choice of music for purposes of belongingness, identity and community building.

Methodology

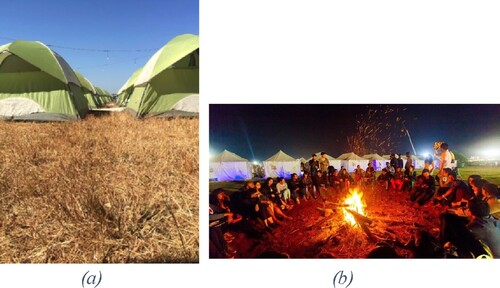

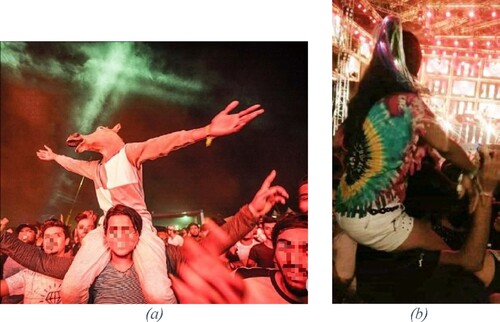

Our methodology comprised participant observation, on-site interactions with festival-goers, and in-depth, semi-structured interviews with 35 respondents. Data gathered during participant observation included field notes, artefacts (wrist bands, leaflets, brochures and so on), and/or visual in-situ data (videos and photographs). During field visits, participants were also recruited for post-festival interviews. These took place in the cities of Ahmedabad, Mumbai, Pune, and Bangalore, at cafés, restaurants, pubs and house parties. The festivals chosen as fieldwork sites were the Sunburn Festival and the Enchanted Valley Carnival (EVC). Sunburn and EVC, along with NH7 Weekender, VH1 Supersonic, and Magnetic Fields are known as the biggest festivals in India based on their footfall and their contribution to the media and entertainment industrial sector according to annual statistical reports produced by KPMG India (2020). Sunburn and EVC were also selected because these festivals, unlike their counterparts, have on-site accommodation for festival-goers (see ), allowing for a deeper ethnographic immersion and more nuanced participant observation. Since its inception in 2007, Sunburn (owned by Percept Limited) has taken place at Vagator Beach in Goa. However, in 2016 and 2017 the event temporarily shifted to the suburbs of Pune, a city near Mumbai, in Maharashtra, due to payment clearanceFootnote1 issues with the local Goa government. EVC (owned by Twisted Entertainment) has been held in Aambey Valley near Pune since 2013 on a barren hill top which has since been christened the Enchanted Village. Each festival has its own unique brand image and brand positioning. While Sunburn claims to be the face of modern Indian EDMC, citing reports on its official website that compare it with international festivals like Tomorrowland (Percept Media Citation2018) and emphasising the featured music artist line up, EVC posits itself as a camping adventure in the hills interposed with its EDM festival identity (EVC India Citationn.d.).

According to Indian youth policy (2019, 2), youth is defined as those between the ages of 15–34 (currently 27.5% of India’s population) (Government of India Citation2019; Ministry of youth affairs and sports Citation2014). Although we apply this State endorsed definition of Indian youth, our participant sample of EDM fans represents a narrower subset of Indian youth. These individuals tend to be urban, English-educated, English-speaking, wealthy and inasmuch ‘privileged’ young Indians. They are young adults who were born and remain in a major Indian metropolitan city or moved there to pursue a professional career. These are also individuals who belong to the generation born during or after the 1991 Indian economic liberalisation. To understand this type of Indian youth culture and its choice in popular music, one has to critically read the recent socio-economic and cultural history of India.

Modern India’s recent socio-cultural and economic trajectory points at two crucial junctures. First, India’s independence in 1947 and its transcendence as a post-colonial nation. Second, the 1991 economic reforms resulting in the transition of the broadcasting media from being State-controlled/owned to operating in an open-market system (Dasgupta, Chakravarti, and Sinha Citation2012). This was set in motion by the satellite revolution (Juluri Citation2003), which had inextricable linkages to globalisation (Dasgupta, Chakravarti, and Sinha Citation2012) and eventually paved the way for electronic media (Chakravarty Citation2019). The satellite era and its multi-channel televised environment helped shape the modern Indian television audience, introducing it to global music cultures via platforms like MTV, Channel [V] and VH1 (Juluri Citation2002). Music television has been a pivotal part of the cultural experience of urban youth who grew up in the post-liberalised Indian society, and eventually came to be described as the ‘MTV generation’ (Zuberi Citation2002). As observed during this study, and also claimed by newspaper articles (Kappal Citation2016) and media reports (FICCI-KPMG Citation2020), the age group and the socio-economic background of EDM festival attendees make it evident how the same 1990s MTV generation and their successors now populate and shape contemporary, commercial EDM scenes in India.

Is there an ‘Indian’ way of raving?

It is a truism that the legacy of Goa Trance remains a dominant point of reference in the global imagination when envisaging the Indian EDM scene. Equally true, however, is that the historical roots of Goa Trance can be credited to a limited group of individuals who were largely made up of non-local bodies. Those who occupied this scene were either ex-patriates of the Portuguese colonial past, and/or tourists arriving from countries including the UK, Germany, Israel, USA, and France. These groups of tourists began to form their own EDMC scenes informed by their transposed hippie culture with the help of artists such as DJ Laurent, Fred Disko, Goa Gill in Goa (St John Citation2012). The Goa trance scene is often romanticised as a marker of how music cultures transcend and travel beyond borders along with young travellers, while its more negative effects are overlooked. Indeed, Saldanha (Citation2002) discusses the inconveniences caused by Goa raves to local villagers due to noise and pollution. However, Saldanha also points out that local villagers have continued to be accommodating of the hippie tourists because their livelihoods were greatly dependent on these raves. For instance, a recurrent visual characteristic of the Goa Trance rave was the presence of women from local villages selling chai (Indian tea), cigarettes, finger food and souvenirs. Another problematic dimension of the hippie tourist influx in Goa, up until the 1990s, was the visible distinctions between different groups of tourists: the locals and the foreigners, wherein the two groups never intermingled, thus assigning a form of racial exclusivity to the Goa Trance rave scenes.

While both Goa Trance and Goa as a physical location have had an influential role on the EDM festivals discussed in this article, it also clear that the contemporary mode of Indian EDMC has largely developed independently of this legacy. It thus becomes important to understand the evolution of the domestic Indian EDM scene in a non-western context, especially when reading it as a site of localised youth cultural performances. There have been key distinctions in the construction and imaging of Goa as a site for its international and domestic tourists. Since its integration within the Indian State in 1961, Goa has undergone perpetual typification that favours certain socio-cultural essentialisations. These narratives of an epitomised Goa, however, differ depending on the intended recipient. On the one hand, the 1990s Goa Psytrance scene thrived on exploring notions of existential orientalism and exoticisation of a space while the scene was occupied with the corporeal presence of white neo-Hippie bodies. On the other hand, aggressively endorsed state-tourism and a rise of globalised, urban Indian middle-class youth created a more domestic imagination of Goa. This was fuelled by mainstream Indian media and Bollywood filmsFootnote2 since the early 2000s wherein Goa was posited as a rite of passage into adulthood for young Indian college-graduates. Due to the presence of international tourists in Goa, it developed in a way that was more accommodating to Western notions of modernity. This allowed Goa to offer to domestic tourists the possibility to facilitate an experience of escaping and transcending Indian traditions and social norms into a performative western modernity. While the dominant representations of the Goa dance music tourist were based on romanticised notions of spirituality laced with Trance music, the local narratives were shaped by ideas of western modernity and hedonistic rites of passage. By the mid-2000s, it became lucrative for local cultural industries in India to capitalise on the imaging of Goa and Percept Media’s Sunburn Festival was established on the beaches of Goa. The late 2000s EDMC however began to transcend Goa, as India witnessed the formation of more domestically patronised EDM festivals across the subcontinent. These festivals, shaped by the presence of local artists and audiences while simultaneously being inspired by the Goa scene, began to articulate their own unique locally informed EDMC identity.

Indian EDMC in its contemporary modality is thus predominantly populated by local bodies while being shaped by trans-local sensibilities. The evolution of the Goa Trance Hippie scene coincided with India’s process of economic liberalisation and a wave of globalisation that largely impacted urban India. By the mid-2000s, this resulted in the coming together of the Goa psytrance scene and the Indian youth who had grown up in the post-liberalised Indian urban scapes. When these individuals discovered and began to populate the Goa scenes, Goa started to re-evolve through the presence and influence of the situated modern Indian youth. Thus, a scene previously given meaning to by the echoes of a global rave culture, began to be re-imagined in a local sense with local sensibilities. The resultant hybrid culture has a liminal essence, being neither an absolute aftermath of the early Goa Trance days nor a direct organic local production of Indian Electronica. This form of hybridity shares a homologous empathy with the section of Indian youth that participates in EDMC performances. Given how the same groups of young adults have been the early adopters of the MTV culture during the 1990s, it becomes apparent how there exists the constant theme of a bi-cultural identity within this group. They face a constant push and pull between what is perceived as Indian and that which is the connotation of being ‘western’ (Saldanha Citation2002). This underpins the creation of a new form of socio-cultural ‘hybridity’, a social category representative of transnationalism (Bhabha Citation1994). From within this schism arises a set of everyday cultural negotiations for scene participants, reifying post-liberal, bi-cultural identities. Scene members thus seek a sense of belonginess and a site of enactment for their fractured and forged identities via EDMC performances.

When asked to describe what attending an EDM festival meant to him, one our respondents neatly articulated the chief elements of the EDM cultural experience:

I can’t really pin-point and tell you that one thing which makes attending EDM festivals worth it, but I can tell you it is a lot of fun to be able to let yourself loose. To be in a crowd that is not judging you. To come together for the love of the same kind of music and to know whatever is happening is for the moment only [ephemeral] is great. It might seem like just another party, one that lasts three days. But the vibes you get here will make the three days mean way more than the rest of the 362 working days of the year and the memories you make here are for life!. (Rizul)

In the subsequent sections of this article, we discuss key themes emerging from our ethnographic data that point to the existence of an Indian way of raving. We begin by deciphering what the cultural negotiations of scene members are, and how they perform these ruptures. This assists in interpreting how a contradictory value system leads to an urgent need for coalescing with others who feel the same on the grounds of an artefact of shared interest, which in this case is a genre of music and the practice of indulging in late-modern dance cultures. Additionally, we identify patterns illustrating how Indian EDMC marks its points of departure from its deeply associated image of being a monolithic spiritual, mystic, Hindu-esque experience, having a religious homology like its predecessor Goa Trance, and demonstrate qualities unique to local cultural sensibilities.

‘Between and betwixt’: understanding the everyday cultural negotiations of Indian EDM fans

Indian EDM fans adopt multiple means to address the quotidian dichotomies that cause urban Indian youth’s identity to be fraught with cultural tensions. Given how EDMC forms the ‘other’ part of their bi-cultural identity which is in constant negotiation with their every-day primary cultural identities, one way of them acting upon this is reflected in their varied use of social networking sites. India is the second-largest country for social media use (Kaka et al. Citation2019), and the respondents of this study constitute India’s ‘digital’ generation, having grown up during an era of rapid digitisation in the country. English educated and with middle class backgrounds, many own smart-phones and are active on multiple social networking sites.

I don’t post everything everywhere, you know? When I go to an EDM festival, you will see a lot of snap-stories. Facebook will just show I am ‘attending’ an event. (Aleeya)

I do not generally post a lot of my party pictures on Facebook because I have my parents and relatives in my friend list. (Dhvani)

Snapchat for EDM parties! Simply because not all the people I know are on my Snapchat. Everyone I know, professional and personal are on my Facebook. I do not feel like sharing so much with them. (Paridhi)

My family is very religious! They will flip out if they see me with beer in my hand and girls by my side. I am more scared of my family seeing such posts than my office colleagues. (Henil)

I don’t want my family or anyone who even lives in my neighbourhood to know I drink, smoke and go to festivals with my boyfriend. It doesn’t matter how old you are, you are always scared of the older generation finding out you do these things. It’s India! Everything happening in such parties/events are considered cultural taboos!. (Trisha)

An a-religious communitas

Several existing EDM studies focus on religious homology within the act of raving, along with displaced religious experience in trance-scenes (Gauthier Citation2004) and techno-shamanism (Hutson Citation1999) that point to direct and/or indirect regio-spiritual connections to certain aspects of EDMC (St John Citation2006). This becomes important vis-à-vis Goa Trance and the Goa scene (St John Citation2012), given how the genre has been documented as displaying strong influences of Hindu iconographies and spirituality (Sylvan Citation2013). As a means of comparing the existing interpretations of the Goa scene with the scene, context and setting of our own research, during our fieldwork research participants were invited to comment on the existing dominant predicative of spiritual efficacies of EDM festivals (Davis Citation2004; St John Citation2014). As the following accounts indicate, for many of our respondents there was a general feeling that EDM offered an alternative to spirituality, with spirituality being considered to be closely associated with religion and traditional ways of life in India:

We have a vast array of religious identities in India. Add to that cricket which becomes a form of non-traditional religion. So when I think of EDM I can’t really think of it in terms of the existing religious understanding in the country. (Mia)

It is very simple. We come here to find something outside our already known surroundings. When we already have garba and holiFootnote3 and other traditional and religious dance festivals why would we want the same experience from EDM festivals? (Henil)

I see no religious or spiritual aspects in EDM festival experiences. Maybe that is because, the way religion is in India is that it is extremely regulated and bounded by rules. [An] EDM festival on the other hand is a land of freedom. We come here to feel free. (Mohit)

Well, pure trance on the beaches of Goa could still be kind of spiritual. But mainstream EDM festivals like EVC and all? Nah, no way, dude. This is a party scene and as an Indian [I] do not think of such parties and religious sentiments to be on the same platform. (Aleeya)

Figure 2. (a) and (b): Photos depicting the usage of the Indian National Flag by respondents at the festival sites.

As a Muslim, I am happy this [is] not like any religious gathering. It is even better than house/office parties because there I give my identity away by just introducing myself. Here, I don’t know the name of the person I am standing next to and they do not know my name. (Rizul)

Religious festivals are fun and also community-driven, yes. But, they are not open for people from [all] religions and that is how EDM festivals are different. Less serious and less rules, you know? (Aleeya)

You think I can eat meat at a religious event? Or wear my fish-net stockings at a religious celebration? No! Here, I can! (Mia)

In order to read the global EDMC phenomenon contextualised within the Indian ethos, we borrow from Ramanujan’s (Citation1989) cultural analysis presented in his study ‘Is there an Indian Way of Thinking? An Informal Essay’. Ramanujan suggests that cultures, much like language, can be distinguished broadly on the basis of being either context-free or context-specific. He uses the rules of grammatology wherein the articulation of a thought can either be contextual or universal (Ahiri Citation2009). Within the grammatical principles of conceptualising language, there are two basic rules: context-free and context-specific. An example of this rule would be how the transformation of a singular form of a word in the English language to its plural state is not universal and depends instead on its characteristics and context (Ramanujan Citation1989). Spoken languages are mostly context-specific while computer languages are context-free (Phullum and Gazdar Citation1982). Ramanujan’s essay aims at decoding the distinguishing factors within the Indian society by using a linguistic trope (Ahiri Citation2009). He analyses Indian society as ‘context-specific’ for its affect-based traits of setting social conventions wherein each cultural performance is predicated on a given context. As opposed to western context-free societies wherein a universal moral code may apply, in a context-specific culture like India, ethical values will change according to the given context. This context is often times informed by traditional religious doctrines and principles that operate across caste/class/ethnic/creed/gender lines. This has an effect on the way the social actor functions, behaves and thinks within cultures (Ramanujan Citation1989).

Ramanujan develops his argument through describing how there are perpetual counter cultural movements that resist the hegemonic social structure. The modernisation project in India, coupled with globalisation, has resulted in the formation of a specific sub-section within the Indian youth, who tend to borrow from the Western lifestyles and feel driven to adopt context-free ideas of sociations. In the late modern age, a context-sensitive society like India thus develops marginalised spaces of alternative cultural performances aimed at building a context-free collective (Ramanujan Citation1989). Raving or EDMC practices, in spite of having gained the mainstream status as a pop-music text, are out of step with the idealised dominant culture in India. In each situated performance, EDMC offers to its subjects an apt site to transcend from one current status (context-free or context-specific) to the other. Again, this is exemplified by some of the observations made by our respondents during our field visits:

It is so annoying to live in a society where others tell you who you are and what categories you belong to based on your career, education and surname. Here I have made so many new friends and I have not asked their surnames till I wanted to add them on Facebook. (Neel)

The simple idea that other women are dressed like you and it is taken as something normal makes me very happy. Out there, on any regular day if I wear my hot pants and tank top people comment, eve-tease [cat-calling] and I get scolded by my relatives. (Trisha)

I like the atmosphere of acceptance at an EDM festival. You are so busy with the music and dancing and chilling that you don’t pay attention to petty differences. Like who is of which religion, who is from a small town or who supports what political party. (Ashfaaq)

There is a sense of sameness. Same rules for all. Same food for all. Same music for all. No one tells you what you can or cannot wear, eat or do because, say, you are a woman. Makes you feel like all are equal, you know. (Aleeya)

Decoding Indian EDMC

As local cultures interact in a globalised context, musics blend together allowing for the local to shape the sounds that have travelled via global flows and been appropriated in local settings. In India, embedded consumerist patterns of the cultural industry mark out EDM as a desirable form of popular culture with the country’s biggest film industry, Bollywood, incorporating the sonic elements of EDM in its music.

Of course, Bollywood makes it possible for EDM to sell. What do you know of rock and roll? Hardly much. Because Bollywood probably saw no money in it. (Paras)

I like EDM in Bollywood, I think Bollywood is redeeming itself by adding such global beats to it. (Mia)

EDM is popular, and Bollywood needs to be relevant. Obviously Bollywood will have EDM songs now. (Henil)

I am happy that more and more people listen to EDM now because of Bollywood. (Jit)

Doctrines of Indian aesthetics have been theorised in The Natyasastra (Nāṭya Śāstra), a Sanskrit treatise credited to the ancient sage Bharata Muni. A significant contribution of this ancient body of work concerns the Rasa theory, centred around the concept of rasa (Rangacharya Citation2014) which is the manifestation of the core emotion (bhava) within the text, this leading to cumulative and collective experience (anubhava) of said manifestation of the emotion within the audience. The Rasa theory asserts that an artistic performance is expected to evoke a rasa (emotive reaction) among the audience. Evocation, however, is not the primary goal. The main purpose is to collectively experience the core emotion of the performative act (Kumar Citation1994). The original text lists eight rasas- Rati (love), Hasya (comedy), soka (melancholy), krodha (wrath), utsaha (gusto), bhaya (fear), jugupsa (repugnance) and vismaya (wonder), these informing the interlocutor elements of a drama and musical text (Rangacharya Citation2014).

Since this form of cultural stimuli-response is deeply embedded within Indian society from ancient Indian communes to modern Independent India, it follows that the principles of rasa theory will be identifiable in contemporary cultural forms such as Bollywood. The rasa theory being haptic allows for Bollywood’s cinematic cipher to be based on affective realism, enacted through its music, musical performances and dance (Rosso Citation2020). The audience, having continuously been exposed to this apparatus also organically shapes its response to musical texts according to this culturally coded guideline. Since electronica moves beyond lyrics, embracing a polyrhythmic essence informed largely by vibrations felt by the bodies at the dance floor, in many ways it speaks to rasa aesthetics of the culturally-informed Indian mind.

Given the a-lyrical quality of the genre, it also becomes easy to bring the sound under the Bollywood project. Mainstream Bollywood films often aim at telling extravagant stories covering all the eight major rasas, and EDM sounds seemed to neatly fit the definition of utsaha (gusto), thus becoming the new sound of party and celebrations within Bollywood projects. As noted by newspaper articles (Press Trust of India Citation2016) Bollywood’s ‘dance songs’ have in the last decade seen a shift in its musical aesthetics and have comfortably adopted and adapted to EDM sounds. When asked where EDM meets Bollywood, respondents had this to say:

You know those dance or club songs where everyone is having a great time in the films! That is where EDM is more common. (Mia)

These songs are called party numbers, no? With things like beat drops and the dub-step like sounds? That is what we dance to at house parties!. (Aleeya)

Party songs in movies are mostly EDM these days. With, you know, the singers dropping beats and repeating lines like party abhi baki hai [the party is yet to be over] and beat pe booty. They are silly but I love dancing to them!. (Paras)

Conclusion

This article has explored how Indian EDMC members form an alternative latent community based on shared choice of popular music consumption and shared social need to culturally perform this choice through acts that reinstate feelings of connectivity, collective sentiment and solidarity without differentiating through other every-day categories of class, caste, religion, ethnicity, sex, and gender. The functionality of this membership can be categorised in three distinct modes, as per the analysis of the ethnographic field visits and the in-depth interviews conducted with the participants of the study. First, there exists a dichotomy in the formation of their identity. In order to be able to negotiate with these cultural tensions informing their identity construction, they look forward to coalescing with others through shared experiences. Second, in order to be able to transcend the communitas beyond the liminality of the festal chronotope, they often use social networking sites to maintain their collective bonds. Activities within online communities are concealed, from families and work colleagues etc., through selective online posting behaviour. In this manner, the cultural dichotomy permeates to the digital disembodied self of the EDMC member. Third, a local sensibility has shaped the current contemporary EDMC in India, which has become even more apparent in the last decade. The last decade has been marked by pivotal shifts exemplified by Sunburn’s burgeoning popularity, Bollywood’s socio-economic strategy toward bringing EDM sonic qualities under its fusion project, and the exponential rise of digital users with India’s telecom providers offering lucrative internet subsidies.

By showing how the local corporeality interprets and shapes a trans-local scene to give it its cultural meaning, this article presents an alternative to the existing narratives of embedded features of religio-spiritual elements of post Goa-Trance Indian dance music. Through the Rasa theory analysis presented in this study, we endeavour to illustrate how Indian EDMC members are culturally informed to respond to the localised EDM phenomenon. This, however, is not the same as the previously and otherwise vastly available readings of latent needs to seek spiritual experiences at rave and/or rave-like sites. This also drives home the point of how Indian dance music, given meaning to by local bodies, is neither limited to nor is an absolute homage to the earlier Goa trance scenes. Contemporary Indian EDMC and its members have their unique cultural characteristics and cultural motivations which indicate an Indian way of raving as opposed to the Goa scene which was more akin to a way of raving in India.

Most of the exiting scholarship on the global-local interconnectedness of youth cultures and popular music are marked by their limited access to the global south. The existing understanding is hence formed based on a restricted focus on cultural and contextual youth cultures of the global north. This article expands the range of such work by focussing on urban youth culture in a global south context. The ethnographic observations presented in our study reveal the marked shifts in the patterns of meaning making, identity and belongingness of urban, globalised Indian youth centred consumption practices of popular music cultures like EDMC. As such, the discussions in this article further elucidate how global popular cultural practices are locally interpreted by local youth through the constant re-shaping and re-imagining of their meanings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The Sunburn organisers ran into issues of clearance of monetary dues with local law enforcement and the State Level Permission Committee chaired by State Tourism Minister in Goa opted to not allow the EDM festival to be organised in 2016 and 2017 (Bennett, Coleman and Co. Ltd., Citation2016).

2 The Bollywood film Dil chahta hai (What the Heart Wants) (2001) which was one of the highest grossing films of its time, marked the beginning of a new phenomenon of positing Goa as the site that enables a rite of passage like experience for the young, urban Indian youth. This theme was revisited using extended tropes in other films like Honeymoon Travels Pvt Ltd (2007) and Dear Zindagi (Dear Life) (2016).

3 Holi is a Hindu festival celebrating spring and Garba is a traditional dance that forms the main element of the 9-day Hindu festival of Navratri.

References

- Ahiri, M. 2009. “Indian Way of Thinking in U.R. Ananthmurty’s Samskara: A Rite for a Dead Man.” 2, 4.

- Albiez, S. 2011. “Europe Non-Stop: West Germany, Britain and the Rise of Synthpop 1975–1981.” In Kraftwerk—Music Non-Stop, edited by S. Albiez, and D. Pattie, 139–162. New York, London: Continuum.

- Arora, G. 2017, August 27. “EDM Will Thrive in India, Says DJ Nucleya.” Deccan Chronicles. https://www.deccanchronicle.com/lifestyle/viral-and-trending/270817/edm-will-thrive-in-india-says-dj-nucleya.html.

- Bakhtin, M. M. 1965. Rabelais and His World (H. Iswolsky, Trans.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Barr, T. 2013. Kraftwerk: From Düsseldorf to the Future with Love. London: Ebury Publishing.

- Bennett, A. 1999. “Subcultures or neo-Tribes? Rethinking the Relationship Between Youth, Style and Musical Taste.” Sociology 33 (3): 599–617. doi:10.1177/S0038038599000371.

- Bennett, A. 2000. Popular Music and Youth Culture: Music, Identity and Place. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bennett, Coleman & Co. Ltd. 2016, November 9. “No More Sunburn in Goa? Organisers to Shift Event to Mumbai or Delhi.” Economic Times. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/magazines/panache/no-more-sunburn-in-goa-organisers-to-shift-event-to-mumbai-or-delhi/articleshow/54270417.cms.

- Bhabha, H. K. 1994. The Location of Culture. London and New York: Routledge.

- Bhat, S. 2014. “Electronic Dance Music Comes of age in India.” Forbes. http://www.forbesindia.com/article/recliner/electronic-dance-music-comes-of-age-in-india/36919/1.

- Bose, M. 2006. Bollywood: A History. London: Tempus Publishing Limited.

- Chakravarty, D. 2019. “Popular Musics of India: An Ethnomusicological Review.” Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies 6 (3): 111–122. doi:10.29333/ejecs/267.

- Dasgupta, S., S. Chakravarti, and D. Sinha. 2012. In Media, Gender, and Popular Culture in India Tracking Change and Continuity. New Delhi: SAGE Publications India Ltd.

- Davis, E. 2004. “Hedonic Tantra: Golden Goa’s Trance Transmission.” In Rave Culture and Religion, edited by G. St John, 254–270. London and New York: Routledge.

- EVC India. n.d. “Our Story [Official Website].” https://www.evc.co.in/our-story.

- FICCI-KPMG. 2020. “FICCI Frames: The Era of Consumer A.R.T: Acquisition, Retention, Transaction (Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report, p. 309).” KMPG India. home.kpmg/in.

- Gauthier, F. 2004. “Rapturous Ruptures: The ‘Instituant’ Religious Experience of Rave.” In Rave Culture and Religion, edited by G. St John, 81–100. London and New York: Routledge.

- Government of India. 2019. “National Youth Policy 2014. (p. 2).” Ministry of youth affairs and sport. https://journalsofindia.com/national-youth-policy-2014/.

- Harris, K. 2000. “‘Roots’?: The Relationship Between the Global and the Local Within the Extreme Metal Scene.” Popular Music 19 (1): 13–30. doi:10.1017/S0261143000000052.

- Haslam, D. 2000. Manchester: England the Story of the Pop Cult City. London: Fourth Estate Limited.

- Hutson, S. R. 1999. “Technoshamanism: Spiritual Healing in the Rave Subculture.” Popular Music and Society 23 (3): 53–77. doi:10.1080/03007769908591745.

- Juluri, V. 2002. “Music Television and the Invention of Youth Culture in India.” Television & New Media 3 (4): 367–386. doi:10.1177/152747602237283.

- Juluri, V. 2003. Becoming a Global Audience: Longing and Belonging in Indian Music Television (Vol. 2). New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Kaka, N., A. Madgavkar, A. Kshirsagar, R. Gupta, J. Manyika, K. Bahl, and S. Gupta. 2019. Digital India: Technology to Transform a Connected Nation, 144. New York: McKinsey Global Institute. www.mckinsey.com/mgi

- Kappal, B. 2016, September 16. “How EDM Became Young India’s poison of Choice.” The Hindu: Business Lines. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/blink/watch/how-edm-became-young-indias-poison-of-choice/article21687362.ece.

- Kumar, K. J. 1994. Mass Communication in India. 4th ed. Mumbai: Jaico Publications.

- Laing, D. 1997. “Rock Anxieties and new Music Networks.” In Back to Reality: Social Experience and Cultural Studies, edited by A. McRobbie, 116–132. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Lawrence, T. 2003. Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-1979. Durham and London: Duke University Press Books.

- Luckman, S. 2003. “Going Bush and Finding One’s “Tribe”: Raving, Escape and the Bush Doof.” Continuum 17 (3): 315–330. doi:10.1080/10304310302729.

- Lull, J. 1995. Media, Communication, Culture a Global Approach. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Maffesoli, M. 1996. The Time of the Tribes: The Decline of Individualism in Mass Society. Thousand Oaks, California, USA: Sage.

- Malbon, B. 1999. Clubbing Dancing, Ecstasy and Vitality. London: Routledge.

- Melechi, A. 1993. “The Ecstasy of Disappearance.” In Rave Off: Politics and Deviance in Contemporary Youth Culture, edited by S. Redhead, 29–40. Avebury: Aldershot.

- Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports. 2014. National Youth Policy of India, 88. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Muggleton, D. 2000. Inside Subculture: The Postmodern Meaning of Style. Oxford: Berg.

- Percept Media. 2018. “Sunburn Festival.” Sunburn. https://sunburn.in/about/.

- Phullum, G. K., and G. Gazdar. 1982. “Natural Languages and Context-Free Languages.” Linguistics and Philosophy 44 (4): 471–504. doi:10.1007/BF00360802.

- Pollock, S., ed. 2016. A Rasa Reader: Classical Indian Aesthetics (S. Pollock, Trans.). New York: Columbia University Press.

- Press Trust of India. 2016. “Bollywood Music Turns Groovier in 2016 with EDM Beats.” India Today. https://www.indiatoday.in/pti-feed/story/bollywood-music-turns-groovier-in-2016-with-edm-beats-667035-2016-12-21.

- Ramanujan, A. K. 1989. “Is There an Indian Way of Thinking? An Informal Essay.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 23 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1177/006996689023001004.

- Rangacharya, A. 2014. The Natyashastra. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers.

- Redhead, S. 1993. “The End of the End-of-the-Century Party.” In Rave off: Politics and Deviance in Contemporary Youth Culture, edited by S. Redhead. Avebury: Aldershot.

- Rosso, F. 2020. “The Communicative Dimension of Dance in Bollywood Movies of the Last Two Decades.” In Spiritual and Corporeal Selves in India: Approaches in a Global World, edited by C. E. de Tapia, and A. Moreno-Álvarez, 138–150. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Saldanha, A. 2002. “Music, Space, Identity: Geographies of Youth Culture in Bangalore.” Cultural Studies 16 (3): 337–350. doi:10.1080/09502380210128289.

- Samarth, G. 2015, August 5. “Electric Fever: Indian EDM Set to Go Global.” Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/music/electric-fever-indian-edm-set-to-go-global/story-6ED3I2ZXX2fEHuMcjtY3CI.html.

- Smith, S. J. 1997. “Beyond Geography’s Visible Worlds: A Cultural Politics of Music.” Progress in Human Geography 21 (4): 502–529. doi:10.1191/030913297675594415.

- St John, G. 2006. “Electronic Dance Music Culture and Religion: An Overview.” Culture and Religion 7 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1080/01438300600625259.

- St John, G. 2009. “Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival.” Dancecult 1 (1): 35–64. doi:10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03.

- St John, G. 2012. “Seasoned Exodus: The Exile Mosaic of Psyculture.” Dancecult 4 (1): 4–37. doi:10.12801/1947-5403.2012.04.01.01.

- St John, G. 2014. “Goatrance Travelers Psychedelic Trance and Its Seasoned Progeny.” In The Globalization of Musics in Transit, edited by S. Krüger, and R. Trandafoiu, 160–184. London and New York: Routledge.

- Sylvan, R. 2013. Trance Formation: The Spiritual and Religious Dimensions of Global Rave Culture. 1st ed. London and New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315024509.

- Turner, V. W. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Zuberi, N. 2002. “India Song: Popular Music Genres Since Economic Liberalization.” In Popular Music Studies, edited by D. Hesmondhalgh, and K. Negus, 238–250. London: Oxford University Press.