ABSTRACT

Education and work are two essential parts of young people’s lives. Currently, the relationship between education and work in the youth policy field is predominantly discussed from the perspective of a narrow economic discourse of education to work transitions. This is despite the fact that this narrow paradigm of examining youth transition from school to work which was prevalent in the 1980s and early 1990s has been consistently problematised and re-worked in the past few decades. Drawing on longitudinal data collected from a cohort of Australian young adults reporting their self-assessment of and their reflections on the connection between their study and work, this paper provides new empirical evidence in support of some of the arguments that have emerged within the field of youth studies regarding transition. Grounded in a broader conceptualisation of transition and informed by theories of youth citizenship, this paper highlights the complexities involved in young people’s navigation of education and work, and proposes the metaphor of a double helix which considers education and work as two interconnected venues through which recognition and meaning are achieved by young people in a postmodern society.

Introduction

The relationship between education and work in young people’s lives is often understood through a ‘master metaphor’ of transition that positions education as necessary preparation for work (Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014). This approach has tended to dominate the identification and measurement of young people’s transition over time. While the metaphor of transition has been central to the intersection between youth studies and youth policy in many Western countries, focussing attention on associations between educational qualifications and the labour market (Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014), it has been consistently problematised and re-worked in the past three decades as a metaphor for understanding young people’s lives within the sociology of youth (Brozsely and Nixon Citation2022; Furlong and Cartmel Citation2007; Hall, Coffey, and Lashua Citation2009). Raffe (Citation2003) summarised the three limitations of this metaphor as: (1) its linearity, which ignores the complexity of young people’s engagement with education and work and the diverse directions of youth transitions in changed social contexts; (2) its economism which focuses on young people’s engagement with the labour market and paid employment while ignoring changes in their engagement with other aspects or spheres of their lives, such as family, relationships, and lifestyles; and (3) its individualism which holds young people solely responsible for the way their lives unfold while ignoring the impacts of social structures and inequality in shaping their trajectories.

These criticisms have been extended and reiterated in more recent studies. Studies of youth policies and young people’s experiences of school-to-work transition highlight the disintegrating nexus between education and work in the current restructured youth labour market (Chesters Citation2020a; Lundahl and Olofsson Citation2014) and the impact of other structural factors such as gender (Wyn et al. Citation2017) and place (Hall, Coffey, and Lashua Citation2009) in shaping young people’s education and work experiences. These critics seem to suggest that the concept of transition is losing its utility in understanding young people’s transitional experiences in a post-modern society.

According to MacDonald et al. (Citation2001), however, these critics’ arguments are based on ‘a narrow and largely outdated picture of the nature of transition studies’ (3), an impression made by the boom in policy-oriented quantitative research in the 1980s which primarily focused on counting and profiling the steps in young people’s pathways from school to work (Roberts Citation2019). In defence of studies of youth transition, MacDonald et al. (Citation2001) highlighted the value and utility of a broad concept of transition in generating ‘sensitive and sophisticated accounts of youth experiences’ in the context of various socio-economic forces that structure their youth phase.

While studies of youth transition have clearly moved on from a ‘rather primitive model of transition’, as MacDonald et al. (Citation2001) described it, the narrow understanding of young people’s transition from education to work as pathways from school to employment has remained a powerful discourse in shaping youth policies to this day (Norton Citation2020). With its focus on the passage of young people living through the portals of education and employment, this discourse reinforces the notion of young people’s relationships with ‘new environments of education and work [being] shaped by neoliberal discourses and policies’ (Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014, 904) without acknowledging that a pathway is an outcome of interactions among relationships, associations, and dynamic patterns of action and coordination (Hayes Citation2012). The (reified) notion of pathway, while alluding to a relationship between education and work, nonetheless positions that relationship as sequential and pre-existing, rather than as simultaneous, relational, and invented by young people.

To disrupt this deep-rooted assumption, alternative metaphors have been proposed by researchers. Examples of these metaphors include ‘yo-yo’ transitions which capture the nonlinearity of young people’s trajectories toward markers of adulthood (Biggart and Walther Citation2006), ‘pinball youth’ which highlights the flexibility in young people’s transitions from education to work (Cuzzocrea Citation2020), and ‘car sharing’ (Magaraggia and Benasso Citation2019) which underlines collective and proactive dimensions of young people’s strategies in negotiating opportunities within contextual constraints. Although these metaphors contributed effective tools to convey the meaning of youth transition in a changed social context in accessible form, they tend to focus on describing what young people’s transition looks like from outside. A metaphor that can help us understand young people’s transition experience from their own perspective is lacking.

For this reason, this paper proposes an alternative metaphor to understand young people’s engagement with education and work in their transition phase. Drawing on mixed-method longitudinal data collected from a group of Australian young people in the Life Patterns program over eight years, this paper provides new empirical evidence about the general patterns reflected in young people’s self-assessments of the relationship between their education and work. It also offers new evidence of the complexities of navigating post-school education and work from their own perspectives. Given this, I argue that instead of seeing one as the means of achieving the other, education and work in youth transition can be more usefully treated as two interconnected forms of social engagement through which young people explore their relationships with society and create meaning for their lives within their social contexts. In light of this empirical evidence, I propose a double helix model as an alternative metaphor to consider the relationship between education and work. An unfolding double helix reflects the constant efforts young people sustain to simultaneously navigate education and work in their lives, building their reflexive self-projects towards meaningful lives.

In the following sections I review the theoretical resources that have informed the research for this paper. I then explain the collection and analysis of the mixed-method data that I draw on to examine young people’s engagement with education and work after leaving school. This is followed by the general patterns of education-to-work transition identified from the quantitative data of participants, and the themes generated from their qualitative reflections on the relationship between their education and work. The empirical data demonstrates the limitations of the ‘primitive model of transition’ (MacDonald et al. Citation2001), a model still prevalent in youth policy field, in understanding the value of and relationship between education and work in young people’s lives. It also informs a double helix representation of education and work as an alternative to consider young people’s engagement with education and work.

Theoretical resources

This research is informed by three theoretical resources. The first is the broad concept of transition (MacDonald et al. Citation2001) within the sociology of youth which has moved on from the narrow focus of youth transition studies on counting and profiling steps in young people’s transition from school to work (Roberts Citation2019); it has progressed to a consideration of multiple interconnected transitions negotiated by young people in a new life course terrain structured by changing socio-economic forces (Hall, Coffey, and Lashua Citation2009; MacDonald et al. Citation2001; Citation2005). This approach has informed ‘sensitive and sophisticated’ understandings of young people’s transition experiences, and showcases the radically altered nature of pathways to adulthood which are unpredictable, insecure, contingent, and self-managed (Harris Citation2015; MacDonald et al. Citation2001). Unlike the deterministic account of trajectories from school to work which preoccupied studies of youth transition in the 1980s, research informed by the broad concept of transition acknowledges young people’s active agency in creating their own biographies within structured conditions rather than treating them as passive victims of structural factors and policies (MacDonald et al. Citation2001; Citation2005).

The second theoretical resource that informs my analysis is the theory of youth citizenship which acknowledges young people as equal citizens who are actively engaged in various forms of social activities (Lister Citation2007). It is through their participatory activities and practices that young people make sense of their relationship with the society, forge their identities, and achieve recognition and meaning in their lives (Fu Citation2021a; Harris Citation2015). These activities and practices are intentionally and voluntarily created by young people in response to their understanding of the social order which recognises their capacity for adaptation and change. As such, it goes beyond the dichotomy of agency and structure to provide a holistic and processual concept that can draw together different frames of analysis in the sociology of youth. Informed by this theory, education and work can be seen as two major forms of social engagement through which young people learn about society and create recognition and meaning in their lives. This view of education and work allows us to step beyond the metaphor of transition which carries undertones that view education as the means and work as its end.

Finally, I use metaphor as a heuristic tool for my theoretical exploration. Metaphor is effective in opening up new thinking spaces for enquiry and articulation beyond existing languages and storylines (St. Pierre Citation1997). The new context a metaphor brings can extend the meaning of the original word, enabling us to see the in-apparent or un-thought aspects of social relationships (Brown Citation1976). The use of metaphor can also scaffold new ways of thinking. The embodied techniques of metaphor allow rich means and possibilities to convey the complexity of a subject (Cahill Citation2022). In this paper I use metaphor to scaffold my thinking of alternative ways to consider the meaning of education and work in youth transition, and employ it as a tool for conveying the complexities of young people’s engagement with education and work through which they create meaning in a changing socio-economic context.

Method

The data analysed in this paper was extracted from the Life Patterns research program, a mixed-method longitudinal research project about Australian young people. This research was approved by the university ethics committee. The cohort of participants in the annual survey was aged 17–18 when finishing high school in 2005, corresponding to the popular notion of generation Y. In order to consider education and work in young people’s lives from a broad perspective of ‘how young people make sense of their experience and actively shape their lives’ (Furlong et al. Citation2011, 360), I use quantitative data to examine the general patterns reflected in young people’s self-assessments of the relationship between their education and work, and qualitative data to unpack the complexities of their experiences of navigating this relationship.

From 2012 to 2019, a quantitative question referring to a set of statements about young people’s study and work was asked annually in each survey. Some examples of the statements include: ‘I am in a job in my field of study’, and ‘I have been looking but have not yet been able to find a job in my field of study’. Participants were asked in each survey to state whether they agreed or disagreed with the statements. This was always followed by an open question asking participants how the statements in the previous question related to their own situations.

For purposes of analysis, participants’ responses to the quantitative question were merged. 339 participants who completed all the eight surveys between 2012 and 2019 were identified. Among these, 71% were female. By 2012, 80% of these participants had completed a post-school course or degree, while 68% held a university degree. By 2019, those who had completed a post-school course or degree had increased to 96%, with 81% holding a university. As can be seen from their level of education, this group of participants is not a representative sample of all young Australians; however, the well-qualified feature of this group is pertinent in understanding the relationship between education and work. Further, their successful engagement with post-secondary education and their challenges and struggles in the labour market serve as points of reflection when considering the kinds of challenges those without post-secondary education face in the employment realm (this latter point is beyond the scope of this paper, however).

On the employment side, those who were working full-time and part-time accounted for 54% and 25% of the 339 participants respectively in 2012, changing to 66% full-time and 19% part-time in 2019; 8% were on parental leave. As for the nature of their working contracts, 51% percent held a permanent contract in 2012, while 21% had a sessional or casual contract. Eight years later, in 2020, this had changed to 71% holding a permanent contract and 11% a limited-term contract, with 5% on a renewable contract and 6% on a casual contract. The quantitative data was aggregated and a descriptive analysis conducted to explore the general patterns of study-to-work relationships from participants’ perspectives.

All the text comments given by participants in each annual survey were collated from the qualitative data collected in response to the open question about the links between their education and work. below shows the year and age of participants at each survey, and the number of comments participants gave to the open-ended question. The length of comments varied from a few words to over 300 words.

Table 1. Text comments collected over the period of 2012–2019.

A thematic analysis was employed to generate themes from these text comments about participants’ experience of their engagement with education and work. I then drew on the patterns and themes identified from empirical data to discuss how the value of education and work, and the relationship between them, can be better understood.

Patterns in the connection between education and work

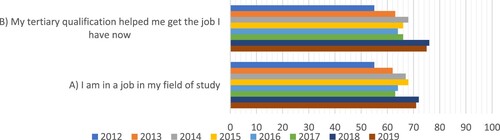

Participants’ responses to statement A (I am in a job in my field of study) and B (My tertiary qualification helped me get the job I have now) () indicate that at the age of 24 (2012) over 50% of the 339 participants agreed that they were in a job in their field of study, also believing that their tertiary qualification helped them get that job. This figure rose in 2013 and 2014, fluctuated between 2015 and 2017, and then rose to over 70 percent in 2018 and 2019. It demonstrates a connection between education and work for most participants (at least after the adjustment period between 2014 and 2018), but it is by no means a linear or straightforward one; rather, the connection involved an extended process of adjustment between education and work domains through retraining or re-engaging with formal education.

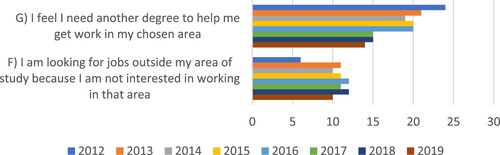

In terms of the capacity of participants to get work in their area of study (), those who felt they needed another degree to achieve this (G) decreased from 24 to 14%. This decrease aligns with the annual survey in 2019 which indicated that 50% of those who agreed they needed another qualification to help them get work in 2012 had completed a post-graduate degree or above by 2019. At the same time, participants who were looking for jobs outside their area of study because they were not interested in working in that area (F) remained relatively stable (around 10%).

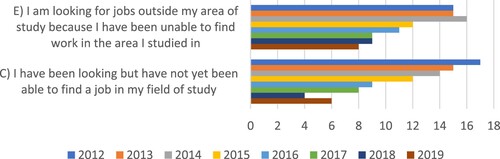

Similar patterns were found among those who agreed with the statements that ‘I have been looking but have not yet been able to find a job in my field of study’ (C) and ‘I am looking for jobs outside my area of study because I have been unable to find work in the area I studied in’ (E) (). This reflects the impact of the structure and composition of the labour market on the employment outcomes of young people with different qualifications and professional skills. These patterns also suggest that after a period of adjustment while engaging with the labour market and accessing further study more participants had managed to find a job in their area of study.

The figures above provide a picture of the general pattern of association between participants’ study and work over eight years. At age 24, six years after leaving school, although 80% of them have completed a post-school course or degree, only slightly more than half of the 339 participants had secured jobs in their area of study. It took another seven years, until 2019, for this to increase to over 70%. The percentage of those who completed a post-school course or degree increased to 96% by 2019, with 81% holding a university degree and 34% having completed a master’s degree. This indicates the lengthy process required to obtain a relatively secure job through continuous engagement with both the labour market and further study. It aligns closely with the concept of new adulthood which is characterised by the extended time span of adulthood in which lines between youth and adulthood are blurred (Wyn and Dwyer Citation2000), and a clear pathway from education to a secure job is absent (Chesters Citation2020b).

While noting the general patterns reflected in young people’s self-assessment of the relationship between their study and work, it is also important to understand the dynamics and complexities of individual perspectives and experiences in connection with that relationship. In what follows I present four key themes emerging from analysis of participants’ comments about their engagement with education and work.

The ‘usefulness’ of education for work

Although studies have shown the disintegration of the education/work nexus in young people’s lives in recent decades (Brozsely and Nixon Citation2022; Chesters Citation2020a), educational qualifications nonetheless remain one of the strongest contributors to young people’s labour market outcomes (Chesters and Wyn Citation2019; Järvinen and Vanttaja Citation2001). Aside from a few rare cases in which participants claimed no link between their education and employment, the majority of participants analysed for this article believed that their education was related to or had contributed to the work they were doing; however, the nature of this contribution varies with some found their study prepared them well for the job in their area of study, others thought their degrees only helped them get a foot in the door or an edge over their competition for a job. One participant commented that.

My tertiary education put me in a better position for my current job as a chef and soon to be business owner, however, it was not directly associated with my qualification. (aged 31, chef and business owner, trade certificate)

In my new role, I certainly utilise the skills I learnt during my degree, including writing and communication with people. (aged 31, senior project officer, university degree)

I took much from my social sciences/environment degree, and it is likely that I will apply skills and knowledge from this study throughout my work and life. I am not working in the field of my highest educational qualifications, but I am happy with this outcome. (aged 31, chef, university degree)

Untold stories about ‘successful’ transition

Although the diagram above shows that most of the participants managed to find jobs in their field of study after an extended period of adjustment, this does not mean they had reached a clear work destination. The comments given by participants reveal an ongoing process of negotiating in which the flows of influence between education and work are mutual. Participants who agreed that they were working in their field of study, the group normally referred to as having transitioned successfully, expressed highly heterogeneous views on this success. For those who were enjoying their job (the most successful in transition terms), further study or training remained an important item on their agenda. Many of them talked about the urge to continue studying for career progression or simply to keep their jobs:

University degree only guarantees you a job as a junior doctor. I will require further degrees/qualifications to become a specialist which I am currently undertaking. (aged 28, doctor, Bachelor of Medicine)

I’m studying the trade side of engineering as I work in it and will try to progress into the design side by getting into a company through the back door trade side. (aged 28, fitter-welder, university degree in Mechanical Engineering)

Since qualifying for my trade, I am much less enthusiastic about working in it for many reasons including the health impact on lifestyle & ethical values, … Over the next two years I will seek further study and a change of occupation. (aged 24, boilermaker, trade certificate)

I am currently working as a lawyer. I am thinking about working as a non-lawyer and I believe I would need to complete further study to move into a new field. (aged 27, lawyer, Bachelor of Law)

you learn about different areas of work when you start working, so exploring alternatives is a priority to get broader experience. (aged 27, analyst, master’s degree)

I currently have a couple of part-time jobs in the field that I studied; however, once I complete my degree, I would like a full-time job in a similar field. I would love a job in the music industry (which is the field I have studied), however, jobs are limited & competitive, so I also work a couple of unpaid volunteer jobs to gain experience & network. (aged 24, music teacher, completed university degree and studying for a master’s degree)

Navigating engagement with education and work in after-school life

Contemporary youth studies research has highlighted the seemingly unlimited choices presented to young people, positioning them as being responsible for making the right decisions in education and work (Wyn and Woodman Citation2006). Such choices represent a significant source of pressure for their after-school life (Cahill Citationforthcoming). Young adults’ reflections on their experiences of navigating education and work related in the text comments in the surveys illustrate some of these pressures. The first is a strong sense of uncertainty in terms of their decisions about education and work, as one participant commented:

I don't feel confident in my choice of career. It is interesting but I keep second guessing on whether it is something I want to do for the rest of my working career. I am afraid that I may regret this career choice in the future, like I missed out on my dreams, but I am not sure what they are! (aged 25, insurance broker, Bachelor of Business)

I still haven't figured out where I want to go. Multiple career tests and seeing a career counsellor hasn't helped. I never knew what I wanted to do when leaving high school. I studied something for the sake of it, found a job in that field because it was the right thing to do – you know you study, you get a job and you’re set. At least that's what my parents did. But I definitely don't see myself working in my field for the next 30 years. I feel like I should just make a decision and go with it, but then there is the fear I'll make the wrong one and just end up back to right where I am now. (human resource coordinator, Bachelor of Business)

The second feature of the navigation of post-school life amongst participants is their concurrent engagement with study and work. This kind of non-sequential engagement with education and work has possibly been apparent since the early 1970s and was well documented in the literature (Price et al. Citation2011; Wyn and Dwyer Citation2000). In some more complicated cases, young people are juggling the working opportunities enabled by their multiple qualifications and study. One participant shared her experience:

I'm working in two completely separate jobs and I have three tertiary qualifications (degree in graphic design, Adv Dip Myotherapy, & I'm currently completing my Masters of Occupational Therapy Practice). My first job is directly dependent on my Adv Dip while my second is working for the OT department at Monash, a direct result of being a current master’s student and having a design degree. I'm re-qualifying partly because I realised I wanted to be in a more stable, profitable, and less physically taxing job but mostly because I realised I wanted a different health care role to the one I have and to get that role I need this master’s. (aged 27, Master of Occupational Therapy Practices, Full-time student)

I successfully completed a trade (Cert. III commercial cookery) but after several years working as a chef I have decided to pursue other careers. I am now using my chef qualification and skills to earn money and support myself while attending university full-time. (aged 24, chef, Certificate III)

I found it difficult to get work in environmental science on its own but was able to find work after learning web development. I am now working for an energy efficiency company as a web developer which is the best of both worlds for me:) (aged 29, web developer, university degree in environmental science)

This year I have found that my car accident has affected who I am and what I want from my life. I have had to learn a lot about myself, my values and what makes me who I am. I have definitely found that my opinions on what is important have certainly changed. (aged 26, engineer, Bachelor of Engineering)

The value of education and work: more than ‘transition’ implies

In reflecting on their engagement with study and work, participants’ comments highlight the intrinsic value of education and work beyond the economic discourse. While some engaged in study with the purpose of pursuing a career in relevant area, others studied believing ‘any learning would help with any career’, still others studying purely for enjoy learning in new areas. Participants’ comments about work highlight their continuing efforts to weave two things into their work: an income for financial independence and the experience of doing meaningful work for self-actualisation and benefiting others (Bailey et al. Citation2019). This is reflected in the comments below:

I need a salary and the mental stimulation from working, and I hope to meet some interesting people, but am otherwise not looking forward to the daily grind of employment for the next 30 + years of my life. (aged 25, research assistant, Bachelor of Arts)

I value career satisfaction and being happy over working in a field that costs me too much personally even if the financial reward is lower. (aged 29, administration and training, Certificate IV in Leadership and Management, Certificate IV in Aeroskills)

I feel like I should want to have a career rather than a convenient job. I'd like my children to be proud of what I do though I’m sure they'd be proud that I contribute to the family. (aged 31, ground handler at airport, post-graduate diploma)

Rethinking the education and work relationship: a double helix model

In parallel with the economic changes in major western societies in the 1980s, such as liberalisation of the economy and emphasis on service and knowledge industries, studies of youth transitions tend to focus on ‘the changing structural situation of young people and the steps they took from school-to-work’ (MacDonald et al. Citation2001, 2), framing the relationship between education and work as primarily an economic ‘pathway’ to financial reward. This approach prioritises the demands of the existing labour market over young people’s need for self-actualisation and civic engagement, both affording social benefit and meaning in life. In this sense, the transition metaphor has obscured the significance of young people’s exploration and grasping of the vast range of possibilities offered by work, citizenship, and life. In view of this, and of the many other deficiencies in the metaphor of transition outlined in the literature, I propose a new metaphor in the form of a double helix () to help account for the nature of young people’s engagement with education and work in current society.

The double helix model, borrowed from genomics, reflects the complexities apparent in participants’ experiences with education and work. The two linked strands that wind around each other stand for the enduring relationship between education and work; they represent the two major forms of social engagement through which young people understand themselves and their relationship to society in their desire to create meaningful lives. The connections between these strands represent the constant negotiation and mutually informing relationship between these two dimensions of life. By placing education and work as two independent strands in young people’s lives, this model emphasises their intrinsic value in young people’s pursuit of meaning. The intertwined nature of these strands denotes their mutually inclusive relationship, with work often encompassing valuable learning or educational opportunities and experience, and education involving young people’s work of engaging with the social institution of school (Dworkin and Dewey Citation1959) as they endeavour to serve the public good (UNESCO Citation2022).

The fact that this model is borrowed from genomics also highlights the significance of creative inquiry and meaningful work as ‘fundamental parts of our human nature’ which should not be supressed or limited by arbitrary coercive institutions (Chomsky and Foucault Citation2015). The arbitrary institution in this paper can be understood as the education-to-work transition discourse, a form of ‘spontaneous sociology’ based uncritically on ‘everyday thinking’ (Wyn et al. Citation2017, 493). This model depicts young people’s engagement with education and work as continuously unfolding rather than reflecting pathways or trajectories marked by steps, significant milestones, or changes. In this way, it concurs with the call to recognise continuity in youth transformations as a ‘mundane register' through which (young) people make and tell their (changing) lives, worlds and places (Hall, Coffey, and Lashua Citation2009, 548).

In genomics, the gene works in a mutually constitutive relationship with both the organism and the environment (Lewontin Citation2001), the environment influencing the gene and its expression while also being influenced by that expression. This is reflected in the double-helix model which understands the education-work relationship as the unique code underpinning the formative process of each individual life within its broader social context. Like a genetic code, the uniqueness of this double helix resonates with the ‘de-standardised’ patterns of transition (Biggart, Stauber, and Walther Citation2001). In the meantime, the contextualised feature of this double-helix model gives expression to the relational approach suggested by other scholars (Brozsely and Nixon Citation2022; Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014) in understanding how young people navigate the opportunities of education and work in the context of different spheres and priorities in their lives. In recognition particularly of the holistic capacity and dynamic, relational character of the concept of belonging (Harris, Cuervo, and Wyn Citation2021), the double helix creates a metaphor that can illuminate that concept. The model also acknowledges both the historical and the temporary dimensions of young people’s life courses which are ‘sensitive to their deep resonance within socio-historical times and places’ (Wood Citation2017, 1183). By accommodating this relational approach, the model reflects the ever-changing but enduring character of young people’s creating of their lives while addressing the limitations of linearity, economism, and individualism implied by the transition metaphor. It acknowledges the multiple directions and purposes of young people’s engagement with education and work which are shaped by, but also contribute to shaping, the opportunity structures in which they live.

In positioning education and work as two independent but closely related forms of social engagement through which young people derive meaning for their lives, this model addresses the limitations of the reductionist approach of transition in examining the meaning of education and work in young people’s lives in today’s society. Education as social participation is more about supporting young people’s exploration and formation of identities and subjectivities (Biesta Citation2015) than about acquiring job-ready qualifications and improving employability. In this sense, education should shift ‘from being primarily a tool for economic advancement toward a wider societal role contributing to capacities to navigate complexity and to contribute to a sustainable society’ (Wyn Citation2014, 11). This is especially the case when large parts of young people’s education and learning these days are embedded in their everyday engagement with different individuals, institutions, and communities beyond formal educational settings (Ito et al. Citation2013). Similarly, work as social participation is more about ‘creative, ecological, reproductive work done in freedom than pure labour for surviving’ (Standing Citation2013). Research has shown that a large part of young people’s work from which they derive meaning is conducted in places such as their homes, in friendship groups, in subculture collectives, and in digital spaces (Vromen Citation2017; Wyn, Lantz, and Harris Citation2012). Work in this broader sense is an avenue through which human beings express their creativity and capacity, and skilfully enact their imaginations. It is how they engage with the world around them as free beings rather than merely functioning as a form of labour power fuelling production processes designed and controlled by others (Marx, K. as cited in Iskander Citation2021).

Through a comprehensive appreciation of young people’s engagement with education and work within specific social contexts, the double-helix model subscribes to the notion of inclusive citizenship in its highlighting of young people’s socially constructive participation (Smith et al. Citation2005). By acknowledging the multiple citizenships and subjectivities young people express and practise in their education and work, it also aligns with Harris’ (Citation2015) argument for using the concept of citizenship to integrate the traditions of youth transitions and youth cultural studies; she maintains that citizenship, being constantly constructed through young people’s current activities, can help to develop understanding about how young people ‘achieve recognition, coherence, meaning’ through various forms of participatory action in late modernity (84). It also accommodates the temporally, spatially, and relationality-sensitive approach proposed by Wood (Citation2017) in thinking about citizenship and transitions of young people by acknowledging the continuity and temporality/contingency in their engagement with education and work and in the identities and subjectivities formed and enacted in this process.

Conclusion

This paper contributes to the critical inquiry of the past few decades into the transition metaphor as a tool for understanding the meaning of education and work in young people’s lives. Drawing on the longitudinal data collected from a cohort of young Australian adults over eight years, it demonstrates the limitations of the reductionist approach of this metaphor in understanding the value of education and work and in framing the relationship between the two; it acknowledges the complexities involved in young people’s navigation of their engagement with education and work as they seek to create economically independent and meaningful lives, while recognising their intrinsic value in achieving these purposes.

In view of these limitations and complexities, this paper proposes a double helix model of education and work as a new metaphor to make visible the new features and complexities of young people’s engagement with education and work in late modern societies. By positioning education and work as two independent but intertwined forms of social engagement, it acknowledges the continuous labour of young people in exploring their relationships with society, finding their identities, and generating meaning through education and work. More importantly, it seeks to break the dominant economic frame for understanding the role of education and work in youth transitions, highlighting the social and citizenship perspectives of education and work which play a critical role in achieving a meaningful life. Borrowing from the field of genomics, this metaphor also describes a continuous formation of a life in dialogue with its broader context; it acknowledges the significance of the historical and social contexts in shaping the ways in which young people’s study and work decisions are made at specific places and times, and the possibilities of these broader social contexts being re-shaped by young people’s engagement with education and work.

Although the neoliberal economic system may be the main force maintaining the transition metaphor as the dominant policy discourse in framing the relationship between education and work over the years, the lack of a tangible metaphor to inform new ways of thinking about education and work may also be responsible for the endurance of this extensively critiqued metaphor in the youth policy field. I hope the double helix model of education and work can be an alternative thinking tool for researchers and policymakers in understanding young people’s lives in changed social conditions, and in making space for discussion of education and work in terms of happy and meaningful lives rather than merely in terms of employment and economic growth. As the concern for people’s wellbeing has seen a transition from Gross Domestic Product to Gross National Happiness as a measure of a country’s success (Centre for Policy Development Citation2022), it is timely to have this discussion on our research and policy agenda.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Johanna Wyn, Hernan Cuervo, and the peer reviewers for their support, feedback, and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bailey, C., R. Yeoman, A. Madden, M. Thompson, and G. Kerridge. 2019. “A Review of the Empirical Literature on Meaningful Work: Progress and Research Agenda.” Human Resource Development Review 18 (1): 83–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484318804653.

- Biesta, G. J. 2015. Good Education in an age of Measurement: Ethics, Politics, Democracy. New York: Routledge.

- Biggart, A., B. Stauber, and A. Walther. 2001. “Avoiding Misleading Trajectories: Transition Dilemmas of Young Adults in Europe.” Journal of Youth Studies 4 (1): 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260120028574.

- Biggart, A., and A. Walther. 2006. “Coping with yo-yo Transitions: Young Adults’ Struggle for Support, between Family and State in Comparative Perspective.” In A New Youth? Young People, Generations and Family Life, edited by E. Ruspini and C. Leccardi, 41–62. London: Routledge.

- Borland, J., and M. Coelli. 2016. “Labour Market Inequality in Australia.” Economic Record 92 (299): 517–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4932.12285.

- Brown, R. H. 1976. “Social Theory as Metaphor On the Logic of Discovery for the Sciences of Conduct.” Theory and Society 3 (2): 169–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00161676.

- Brozsely, B., and D. Nixon. 2022. “Pinball Transitions: Exploring the School-to-work Transitions of ‘the Missing Middle’.” Journal of Youth Studies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.2058357.

- Cahill, H. 2022. “Using Metaphors to Cross the Divide between Feminist Theory and Pedagogical Design.” Gender and Education 34 (1): 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2020.1723496.

- Cahill, H. Forthcoming. “Resilience in Transitional Times.” In Handbook of Transitions into Adulthood in the 21st Century, edited by C. Leccardi and J. Chesters. London: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Centre for Policy Development. 2022. Redefining Progress: Global Lessons for an Australian Approach to Wellbeing. Centre for Policy Development. https://cpd.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/CPD-Redefining-Progress-FINAL.pdf.

- Chesters, J. 2020a. “The Disintegrating Education-work Nexus.” In Youth and the New Adulthood: Generations of Change, edited by J. Wyn, H. Cahill, D. Woodman, H. Cuervo, C. Leccardi, and J. Chesters, 47–65. Singapore: Springer.

- Chesters, J. 2020b. “Preparing for Successful Transitions between Education and Employment in the Twenty-First Century.” Journal of Applied Youth Studies 3 (2): 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43151-020-00002-8.

- Chesters, J., and J. Wyn. 2019. “Chasing Rainbows: How Many Educational Qualifications do Young People Need to Acquire Meaningful, Ongoing Work?” Journal of Sociology 55 (4): 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783319888285.

- Chomsky, N., and M. Foucault. 2015. The Chomsky-Foucault Debate: On Human Nature. The New Press.

- Cuervo, H.. 2022. “The Problem of “Normalization” in Educational Justice.” In Educational Justice: Challenges For Ideas, Institutions, and Practices in Chilean Education. Vol. 257, edited by Camila Dávila, 257–266. Santiago de Chile: Ediciones Universidad Alberto Hurtado.

- Cuervo, H., and J. Wyn. 2014. “Reflections on the Use of Spatial and Relational Metaphors in Youth Studies.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (7): Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.878796.

- Cuzzocrea, V. 2020. “A Place for Mobility in Metaphors of Youth Transitions.” Journal of Youth Studies 23 (1): Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1703918.

- Dworkin, M., and J. Dewey. 1959. Dewey on Education: Selections with an Introduction and Notes by Martin S. Dworkin. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Fu, J. 2021a. Digital Citizenship in China: Everyday Online Practices of Chinese Young People, Vol. 12. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-5532-6.

- Fu, J. 2021b. “Angry Youth or Realistic Idealist? The Formation of Subjectivity in Online Political Participation of Young Adults in Urban China.” Journal of Sociology 57 (2): 412–428. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783320925143.

- Furlong, A., and F. Cartmel. 2007. Young People and Social Change. 2nd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Furlong, A., Woodman D., and Wyn J.. 2011. “Changing times, changing perspectives: Reconciling ‘transition’ and ‘cultural’ perspectives on youth and young adulthood.” Journal of Sociology 47 (4): 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783311420787.

- Hall, T., A. Coffey, and B. Lashua. 2009. “Steps and Stages: Rethinking Transitions in Youth and Place.” Journal of Youth Studies 12 (5): Article 5. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260903081665.

- Harris, A. 2015. “Transitions, Cultures, and Citizenship: Interrogating and Integrating Youth Studies in New Times.” In Youth Cultures, Transitions, and Generations, edited by Dan Woodman and Andy Bennett, 84–98. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Harris, A., H. Cuervo, and J. Wyn. 2021. Thinking about Belonging in Youth Studies. Switzerland: Palgrave.

- Hayes, D. 2012. “Re-engaging Marginalised Young People in Learning: The Contribution of Informal Learning and Community-based Collaborations.” Journal of Education Policy 27 (5): 641–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2012.710018.

- Iskander, N. 2021. Does Skill Make Us Human? Migrant workers in 21st-century Qatar and beyond. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Ito, M., K. Gutiérrez, S. Livingstone, B. Penuel, J. Rhodes, K. Salen, Juliet Schor, S.-G. Julian, and S. C. Watkins. 2013. Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design. Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

- Järvinen, T., and M. Vanttaja. 2001. “Young People, Education and Work: Trends and Changes in Finland in the 1990s.” Journal of Youth Studies 4 (2): 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260120056988.

- King, A. 2011. “Minding the gap? Young People’s Accounts of Taking a Gap Year as a Form of Identity Work in Higher Education.” Journal of Youth Studies 14 (3): 341–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2010.522563.

- Lewontin, R. C. 2001. The Triple Helix: Gene, Organism, and Environment. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Lister, R. 2007. “Inclusive Citizenship: Realizing the Potential.” Citizenship Studies 11 (1): 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621020601099856.

- Lundahl, L., and J. Olofsson. 2014. “Guarded Transitions? Youth Trajectories and School-to-work Transition Policies in Sweden.” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 19 (Sup 1): Article sup1. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2013.852593.

- MacDonald, R., P. Mason, T. Shildrick, C. Webster, L. Johnston, and L. Ridley. 2001. “Snakes & Ladders: In Defence of Studies of Youth Transition.” Sociological Research Online 5 (4): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.552.

- MacDonald, R., T. Shildrick, C. Webster, and D. Simpson. 2005. “Growing Up in Poor Neighbourhoods: The Significance of Class and Place in the Extended Transitions of ‘Socially Excluded’ Young Adults.” Sociology 39 (5): 873–891. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038505058370.

- Magaraggia, S., and S. Benasso. 2019. “In Transition … Where to? Rethinking Life Stages and Intergenerational Relations of Italian Youth.” Societies 9 (1): Article 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc9010001.

- Norton, A. 2020. 3 Flaws in Job-Ready Graduates Package Will add to the Turmoil in Australian Higher Education. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/3-flaws-in-job-ready-graduates-package-will-add-to-the-turmoil-in-australian-higher-education-147740.

- Pais, J. M., and A. Pohl. 2003. “Of Roofs and Knives. The Dilemmas of Recognising Informal Learning.” In Young People and Contradictions of Inclusion, edited by Andreu Blasco, Wallace McNeish, and Andreas Walther, 223–241. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Price, R., P. McDonald, B. Pini, and P. B. Pini. 2011. Young People and Work. Taylor & Francis Group. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=797527.

- Raffe, D. 2003. “Pathways Linking Education and Work: A Review of Concepts, Research, and Policy Debates.” Journal of Youth Studies 6 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1367626032000068136.

- Rizvi, F. 2012. “Mobilities and the Transnationalization of Youth Cultures.” In Keywords in Youth Studies: Tracing Affects, Movements, Knowledges, edited by N. Lesko and S. Talburt, 191–202. New York: Routledge.

- Roberts, K. 2019. “Structure and Agency: The New Youth Research Agenda.” In Youth, Citizenship and Social Change in a European Context, edited by John Bynner, Lynne Chisholm, and Andy Furlong, 56–66. London: Routledge.

- Smith, N., R. Lister, S. Middleton, and L. Cox. 2005. “Young People as Real Citizens: Towards an Inclusionary Understanding of Citizenship.” Journal of Youth Studies 8 (4): 425–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260500431743.

- Standing, G. 2013. A Precariat Charter: From Denizens to Citizens. London: Bloomsbury.

- St. Pierre, E. A. 1997. “An Introduction to Figurations-a Poststructural Practice of Inquiry.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 10 (3): 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/095183997237115.

- UNESCO. 2022. Reimagining our Futures Together: A new Social Contract for Education. UNESCO.

- Vromen, A. 2017. “Digital Citizenship and Political Engagement.” In Digital Citizenship and Political Engagement: The Challenge from Online Campaigning and Advocacy Organisations, edited by Ariadne Vromen, 9–49. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wood, B. E. 2017. “Youth Studies, Citizenship and Transitions: Towards a New Research Agenda.” Journal of Youth Studies 20 (9): 1176–1190. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2017.1316363

- Wyn, J.. 2014. “Conceptualizing Transitions to Adulthood.” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education (No. 143, Fall 2014): 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20100

- Wyn, J., H. Cuervo, J. Crofts, and D. Woodman. 2017. “Gendered Transitions from Education to Work: The Mysterious Relationship between the Fields of Education and Work.” Journal of Sociology 53 (2): Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783317700736.

- Wyn, J., and P. Dwyer. 2000. “New Patterns of Youth Transition in Education.” International Social Science Journal 52 (164): 147–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2451.00247.

- Wyn, J., S. Lantz, and A. Harris. 2012. “Beyond the ‘Transitions’ Metaphor: Family Relations and Young People in Late Modernity.” Journal of Sociology 48 (1): 3–22.

- Wyn, J., and D. Woodman. 2006. “Generation, Youth and Social Change in Australia.” Journal of Youth Studies 9 (5): 495–514. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260600805713.