ABSTRACT

For a long time, youth have been seen as a driving factor for conflicts or as victims of conflicts. While some literature and research on youth in conflict tend to be overly negative and focus on the danger posed by youth, we argue that these descriptions do not reflect reality: youth are crucial to sustainable peacebuilding and must, therefore, be included in conflict transformation processes. We demonstrate that while youth continue to experience difficulties in overtaking meaningful roles as actors of change in peacebuilding, there is an improvement in the acceptance of their agency. The article explores the case of Sierra Leone where the perception of youth can be seen as a massive change from immediately after the war to today. The article explores different roles that youth can have during and after a conflict, investigates positive impacts youth can have, describes what peace means for young people and how they would describe a desirable future, and finally speaks about how youth respond and interact with international ideas of peace and sustainability.

1. Introduction

The potential of youth as drivers of conflict transformation in post-conflict societies is the subject of a growing research agenda. Research portrays youth as important peace actors that hold significant power and collective agency in peacebuilding (Berents and McEvoy-Levy Citation2015; McEvoy-Levy Citation2012; Schwartz Citation2010). This paper builds upon this and sheds light on the debate of youth as drivers for peace. With empirical data from Sierra Leone, it investigates the changing role and perception of youth, their motivation to be peacebuilders, and their hopes and dreams. The paper argues that youth agency in peacebuilding is more and more accepted, yet youth face challenges in their work. This paper thus contributes to (1) the changing roles and perceptions of youth in regard to peacebuilding, their wishes as well as challenges, (2) the field of everyday peace where locals thrive to contribute to the peacebuilding process in their country (Mac Ginty and Firchow Citation2016), and (3) the relationship of youth and youth-led-organizations with civil society organizations (CSOs ) ().

In this paper, we define ‘young people’ or ‘youth’ as a socially constructed cohort (Özerdem and Podder Citation2015) that changes with their societal background. Youth are neither dependent children, nor fully independent and socially responsible adults (Waal Citation2002) Hence, ‘youth-hood’ describes the developmental phase between childhood and adulthood. Due to differing definitions of youth among institutions and organizations in terms of age-rangesFootnote1, we follow the Sierra Leonean government that set 35 as the maximum age for youth with the additional note that ‘[it] does not exclude any young Sierra Leonean liable to Youth related needs, concerns and influences’ (Government of Sierra Leone Citation2003).

The young population of the African continent and its large number of peacebuilding programs (UN Citation2019) make this continent vital for research on youth in peacebuilding. In contrast to previous research (Richards Citation1996),youth are now understood not as inherently violent but as subjects to structural violence, bad governance, marginalization, and exclusion, forcing them into violent structures. It is acknowledged that ‘any viable solution for peace and stability in the African continent needs to take into account the needs, power, and potential of the youth’ (Kasherwa Citation2020, 124). This highlights the need for research with youth activists in peace work to get insights into their perceptions and experiences reflecting both their youth identity as well as their professionalism in the field of peacebuilding.

For this research, the case of Sierra Leonean youth and youth organizations in peacebuilding is the most suitable because the perception of youth has significantly changed over time. From being seen as one of the conflict drivers in the war (Richards Citation2005), to youth activists in the post-conflict phase (Fanthorpe and Maconachie Citation2010), who play an active role in peace processes and contribute to their communities building a stable future (Bolten Citation2019).

To explore this case, this paper firstly introduces the various perspectives on youthand those working in youth organizations, secondly presents the method of data collection, and thirdly examines the general conceptualization of youth in Sierra Leone describing what peace and sustainability mean for youth and how they define a desirable future. The paper closes with the analyzes of responses and interactions with CSOs and presents ideas of peace and sustainability.

2. Young people and peacebuilding

Although young people make up most of the world’s population and their exclusion can hinder long-term peacebuilding, they have largely been ignored and marginalized in peace research (Pruitt Citation2013). In recent years, more research has focused on youth in peace processes, where youth are seen as a positive driver (Simpson Citation2018). Overall, three different perspectives on youth in conflict and post-conflict situations can be identified: (1) young people as victims, (2) young people as conflict actors, and (3) young people as productive forces in peacebuilding. It should be noted that these perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Young people can fall under different categories, depending on a self-definition or a definition by others. Also changes over time are possible.

The first generalizing perspective is young people as victims. Youth are described as passive, innocent victims who need protection (Park Citation2006). Violent conflicts impact youth physically and psychologically and destroy their social systems, economic, and educational structures (Berents and Mollica Citation2020) with devastating effects on their developmental phase (Smith and Smith Ellison Citation2021). Illiteracy, poverty, and high rates of unemployment can lead to the marginalization of youth and exclusion from social, economic, and political life, which will disadvantage them in the future (Del Felice and Wisler Citation2007). Within this perspective falls the notion that youth as child soldiers are both victims and perpetrators (Cohn and Goodwin-Gill Citation2003), when being hired or forced into armed groups to fight or work in ancillary roles (Haer Citation2019).

The second perspective is youth as violent actors. It is argued that young people who grew up in a violent setting are likely to use violence themselves (Haer Citation2019) or use violent means to make themselves heard (Ezemenaka Citation2021). Here, a common interpretation is that large youth cohorts make countries more vulnerable to political violence since they do not see alternative options to fighting (Jimenez and Murthi Citation2006). This argument has been criticized over time but is still used as a baseline for other explanations, such as an underlying ‘youth crisis’ where youth rebel against the current system (Richards Citation1996). There are two different understandings of the youth crisis: ‘(i) a societal crisis impacting on youth, resulting in a feeling of ‘uneasiness’ in the face of societal changes and constraints; or (ii) a crisis originating from youth and impacting on society at large’ (UNDP Citation2006, 21). The first is observed in youth migrating to larger cities, which is identified as a pull factor for joining gangs leading to gangsterism, and violence (Amambia et al. Citation2018; Distler Citation2019). Another pull factor for youth violence was found on the internet, which is perceived to facilitate radicalization through propaganda (Kurtenbach Citation2018).

The third perspective is youth as peacebuilders. It has become increasingly important and challenges traditional notions of youth (Berents and McEvoy-Levy Citation2015; Berents and Mollica Citation2020). Research highlights the agency of young people (Peace and Security Council of the African Union Citation2020) and their ability to react to insecurity and contribute to peacebuilding (Simpson Citation2018). The latter received increasing attention within the international community, leading to the United Nations (UN) Security Council Resolution 2250 (UN Citation2015). However, studies show that the agenda and especially participatory work often lack a meaningful implementation (McEvoy-Levy Citation2011).

One observation that appears in all perspectives is the use of ‘youth’ as a political label that forces young people into a social position with however adversary effects (Christensen and Utas Citation2008). This label is (miss)used to politicize, for example for campaigns by stakeholders in their communities or by politicians for election violence and protests (Bolten Citation2019). On the other hand, it can also strengthen the youth in their role as activists.

2.1 Civil society organizations and young people in peacebuilding

The growing importance of youth actors can also be observed in the work of CSOs. Since the early 2000s, more CSOs have focused on supporting young people in times of transition (Ackermann et al. Citation2003) and youth-based programs have become a priority for donors (Nagel and Staeheli Citation2015). This led to international CSOs becoming one of the three main funding sources for locally-led youth organizations, and topics and ideas promoted by international CSOs are now mainstreamed in local youth organizations.

As studies have shown, youth-led organizations rely heavily on volunteers who make up around 97% of their staff (UNOY and Search for Common Ground Citation2017). Youth’s motivations are ‘valuable experience, self-esteem, awareness, voice, social status, and larger and more diversified social networks’ (UN Volunteers Citation2017, 3), as well as the search for leadership opportunities, recognition by stakeholders, working against harmful factors (Kasherwa Citation2020), the chanceto engage with issues affecting their home (Yea Citation2018), gain of personal reputation (Murata and Nishimura Citation2016) and achievement of career goals (Hajjaj and Mandysova Citation2017). However, young people in youth-led organizations face several challenges including a lack of funding, insufficient support from other organizations (Kasherwa Citation2020), and structural challenges in the form of threats by security agents, governments, and others (Njoku Citation2020). Yet, young people remain actively involved as they understand their work as an important counter space (Yea Citation2018), and an emancipation process in which ‘young people have to overcome dominant social norms that exclude them from participating in public space’ (Tainturier Citation2016, 20–21). This becomes evident in the case of Sierra Leone which will be introduced in the next paragraph.

2.2 The case of Sierra Leone

Although Sierra Leone is considered a post-conflict country after the UN intervention in 2002, the civil war still plays an important role. The causes of the war in Sierra Leone have been manifold, ranging from political instability to resource conflicts, spillover effects as well as demographic issues and inequality. Looking at the demographics there are different viewpoints regarding the roles of young people in the war. The first is the underlying ‘crisis of youth’ (Richards Citation1996). Before the war, young people faced various economic and social challenges, including a lack of education and other opportunities due to the elite system in the country. Through neo-patrimonial practices and armed rebellion, youth sought to fight for their causes. This was seen as ‘a plea for attention from those who felt they had been forgotten’ (Keen Citation2003, 78). The second viewpoint is the desire of young people to gain power, to change the political system resulting in Pan-Africanism ideas and a ‘rebellious youth culture’ dating back to the 1970s (Abdullah Citation2004). With rising tensions in the country, this anti-establishment culture led to violent clashes, and eventually resulted in youth participation in war activities and the creation of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) (Rashid Citation2004). When the Sierra Leonean civil war erupted in March 1991 caused by the insurgency of the RUF, the rebel group gained popularity, especially among young people (Richards Citation2005), leading to the recruitment of approximately 70,000 youth and children (Lansana Citation2005). The third viewpoint on youth involvement is, that they were never in powerful positions in the RUF and therefore had been wrongly accused of their negative implications. After the war, both notions – the continuation of their difficult situation as well as being used by elders for their own socio-political interests are observed (Fanthorpe and Maconachie Citation2019; Tom Citation2014).

All three viewpoints on the role of young people remain relevant anchors for how young people are seen today. The promises of reconstruction and rehabilitation in the aftermath of the war were not completely fulfilled, and not all causes of the conflict were eliminated. Especially, the situation for youth remains challenging. Youth still lack skills and education, do not find jobs, and struggle to make a living (Interview Peacebuilding Network). Despite the completion of the resolution attempt of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) as well as the strong and successful involvement of local and religious leaders in the peace process, mistrust, and latent tensions continue. Because of this, especially older people see young people as a risk factor for stability in the country – a stereotype among others that young people try to dismantle. The commitment of young people to overcome these demonstrates that these generalizing viewpoints need to be challenged and that youth make important contributions to a peaceful country.

3. Methodology

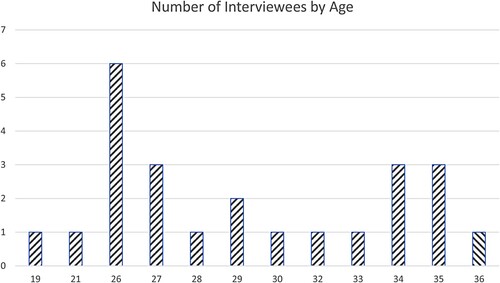

To investigate how youth in Sierra Leone try to overcome these stereotypes through their commitment to youth organizations, we interviewed a total of 29 young people (21 males and 8 females) between 19 and 36 years of age with a median of 27.5 years of age. Although one interviewee exceeds the maximum age of 35 in our definition, we includ the findings of this interview in the results since the experience of the interview corresponds with the addendum of the Sierra Leonean’s definition of youth. Interviewees were chosen because of their multilayered identities as young people and agents for young people through the work of youth CSOs. Based on their experiences as youth, they have an intrinsic motivation to work for youth organizations to foster the agency of young people and counter stereotypes. While it could be argued that the intertwined identities make it difficult to distinguish when interviewees spoke for or as young people, we believe the identities and experiences align and inform each other and cannot be separated. Hence, interviewees speak as young people with experiences of young people, as well as actors of change working for youth CSOs.

Our first interview partners were selected through an online search of organization websites, newspaper articles, and Facebook pages. The selection criteria were that organizations identify as youth organizations and work on youth-related topics. From there, further interviewees were generatedfollowing the snowball sampling method (Parker, Scott, and Geddes Citation2019). We were able to interview volunteers and employees of 22 different organizationsFootnote2 with an average of 8.5 years of working experience with their current organization. Interervieweeshad different roles and responsibilities, ranging from volunteers to directors, and experiences in the fields of education, training, and skills development as well as advocacy and awareness raising, on topics of gender inequality, gender-based violence, violence against students as well as policy development. Due to their association with youth CSOs and to protect the identity of our interviewees, their statements and thoughts are quoted under the respective CSO they work for.

We used qualitative, semi-standardized, guided, online interviews to ensure a structured interview providing relevant information for our research. The questionnaires were developed based on a literature review on youth involved in peacebuilding, perceptions about youth, and the work of CSOs. As the internet is increasingly embedded in the work of researchers and CSO activists, we decided to use video conference tools to conduct our interviews. Limitations were that not everyone had access to a stable network and a safe, quiet space. Therefore, we ensured that interview partners could use the office space of a CSO to speak freely and to eliminate expenses. Technical difficulties sometimes forced us to turn off the cameras to stabilize the connection, which hindered an interpretation of nonverbal communication. Similarly, online interviews limited personnel interaction with interview partners before and after the interview. Although they create a certain distance and cannot substitute interaction in the field (Jackson Citation2021), they still provide good insights into the work of the organizations and interviewees (Ruppel Citation2020).

All interviews were transcribed and then coded with maxQDA a tool for computer-based qualitative and mixed method analyzes based on the inductive category development. Our analysis yielded 25 categories, falling under the six main categories Information about Organization, Cooperation, Personal, Challenges, Opportunities, and Peace. The most salient topics were the interviewees ‘motivation’, their organizational ‘aims’, ‘peacebuilding without youth’ and the ‘situation in the country’.

Considering the research ethics, we ensured that interviewees were not threatened by their participation by conducting a do-no-harm analysis (Anderson Citation1999) and reflecting on the potential factors of re-traumatization (Cronin-Furman and Lake Citation2018), the particularly sensitive handling of research data corresponding considerations on publication strategies (Fujii Citation2009), and the influence and position of power of the researcher (Goodhand Citation2000). In concrete terms, this means that all research participants were informed about the research interest, consent, and data protection. We offered participants opportunities to be involved in the research process after data collection through the interpretation and writing process by sharing drafts of the article for feedback. At the end of the interviews, interviewees could ask questions. This change of roles gave us the chance to reflect on Western definitions, concepts, and perspectives. By using this inclusive research process and following a co-constructive approach (Wilkinson Citation1998), we wanted to understand and construct different meanings and include more collective knowledge (Flinders, Wood, and Cunningham Citation2016).

4. Results and discussion: Young people and CSOs peacebuilding in Sierra Leone

Overall, our analysis provided us with interesting insights into the various perceptions of youth activism in Sierra Leone. It showed that, while youth continue to experience difficulties in overtaking meaningful roles as actors of change in peacebuilding, there is an improvement in the acceptance of their agency. They still feel disadvantaged through political and societal structures, but also when working for CSOs. Yet, there is a change in the perception of youth as inherently violent toward youth as drivers of peace. Youth activists and youth CSOs demonstrate the relevance and power to contribute to sustainable peace and development through their work for and with CSOs on the communal, national, and international levels. This helped them to become versatile and inventive actors to mitigate challenges and difficulties. The following paragraphs will elaborate on the conceptualization and understanding of young people in Sierra Leone, their desire for peace and sustainability, and their interactions with CSOs.

4.1 Conceptualization and understanding of young people in Sierra Leone

The situation of young people in Sierra Leone remains challenging. In particular, the lack of opportunities and support from the government were often named as risks for youth and the country during our interviews. ‘[W]e have the energy in young people that some fall into trouble and problems because of the lack of opportunities and become part of conflicts’ (Interview WAYN). Youth suffer from the consequences of war: ex-child soldiers face reintegration difficulties (Shepler Citation2005), feel disadvantaged by the government and limited in their potential (Interview Education for All).

One of the roots of this problem are the hierarchical social structures with a clear division of power and authority between youth and elders (Tom Citation2014). Youth have often little power in community decision-making structures, as ‘old people have been projecting their own experiences and goals onto the young people’ (Interview PAN). Chiefs and elders hamper youth from gaining a social status and have control over them, which leads to a high level of frustration (Interview GYNP). One interviewee expressed this stating that ‘it can be challenging to convince people to work with us. You feel that we are a post-war country and people are very harsh in the work and actions they are doing. So, people do not want to talk to you, and it takes long to get through them’ (Interview YACAN). Another interviewee said that ‘[We as] young people have a unique knowledge about ourselves, our communities. Elder people cannot speak on our behalf. We know better what we need. [They] often say that we are young too, but our youth is different, the time and era is different. We should be actively involved, not passively’ (Interview YACAN).

Despite the ongoing understanding of youth as potentially violent actors, the perception of youth has changed. Programs advocate and encourage people to provide space for marginalized groups like youth and women, so they can become meaningful members of communities (Tom Citation2014). Intergenerational dialogue and the integration of marginalized groups help to shape youth agency and dismantle existing tensions between generations. This is reflected in the TRC report, which encouraged politicians and the civil society to integrate youth into political processes. The realization of some of the TRC’s recommendations eventually helped youth to gain a positive image as reliable actors (Mitton Citation2009). Although the government, CSOs, and international organizations promote sensitization programs to solve intergenerational disputes, not all youth see the results of the work of the TRC and the government efforts. One interviewee remarked that ‘young people realize that the government will not help them, but they need to help themselves’ (Interview National Youth Commission).

Changing the narrative of ‘violent youth’ to ‘youth as peacebuilders’ is challenging and requires the commitment of the whole society. One interview stated that ‘the greater development of a child has a greater impact on the world and that the young people need support, so they can grow up in a system and be ambassadors and role models. But they cannot do it by themselves, they need assistance’ (Interview WAYN). Over time, and due to active engagement of youth in various spheres, it was acknowledged that youth are not inherently violent, but that social, political, and economic conditions facilitated the recruitment of youth during the civil war (Mitton Citation2013). Youth do not just become violent but that circumstances like structural violence, bad governance, marginalization, and exclusion of young people coerce them (Interview CPNC).

4.2 Young people and their desire for peace and sustainability

The global study of the UN on the ‘missing peace’ has shown that youth have created a strong image of their desired peace: youth acknowledge that peace and sustainability require an end to the underlying causes of violence, such as corruption, social injustice, and inequality, which will foster the feeling of belonging, stability, dignity, the absence of fear, and the overall idea of freedom (Simpson Citation2018). Freedom was also one of the key elements mentioned by our interviewees. ‘[P]eace means that I will live a life free from fear, free from intimidation, free from discrimination, free from war, free from instability, free from prejudice, free from poverty’ (Interview YACAN). Peace is however identified as a social process that requires a high level of participation from all parts of society (ibid.). Without the inclusion of youth in peace processes problems like the lack of education and job opportunities could either remain or increase (Interview GYNP). Therefore, in countries like Sierra Leone, where ‘youth are the biggest part of the population, [they] need to be included in every process in order to push themselves and the country forward’ (Interview Jem’s Argo Business).

The strong desire for peace is reflected in the interviewees’ wishes for a sustainable and peaceful future, the wishes for their peers and family, and the wishes for their country. Youth wish for better education systems, to promote the role of youth in the country, so ‘they can maintain peace in the country’ (Interview SAVE-SL). When education is based on values like peace, critical thinking, and non-violent conflict resolution, it fosters personal development and the sustainable development of the country and eventually provides better job opportunities, stability, and security (Interview YACAN). Another wish is gender equality and the end of gender-based violence. Our interviewees highlighted that both issues are a major challenge in the country and that they want to see a future where everyone is equal. On a political level, youth aspire greater opportunities and participation in electoral processes and policymaking provided by their governments and other political institutions, including more opportunities to take leadership roles (Interview Young Peacebuilders Initiative).

These desires come along with challenges on three different levels: (1) the political level, (2) the societal/communal level, and (3) the individual level. On the political level, youth organizations experience problems of financial support or the politicization of their work. Although the Sierra Leonean government gave promises to support youth, our interview partners criticized political institutions for not responding quickly and effectively to organizational requests (Interview LAMSL). Another criticism is that there is not enough space for youth in politics and the government prefers organizations that align with their political agenda. The work of youth is often used for political purposes (Christensen and Utas Citation2008). Organizations are labeled as political opposition and their work is delegitimized (Interview GYNP). However, ‘there are also politicians who support [their] work and appreciate what [they] do’ (Interview Young Peacebuilders Initiative).

On the societal/community level, the social hierarchies within the Sierra Leonean society are a major challenge for youth seeking to take responsibility. According to our interviewees, this happens when youth are working on topics like human rights, youth development, sexual and reproductive health, gender-based violence, patriarchal structures, cultural differences, and safe-spaces. There appears to be a lack of interest, or resistance within communities since these ideas are perceived to undermine religious and cultural traditions and hierarchies. Interviewees reported physical violence and threats because of their work. Authorities in the communities are afraid of their influence. They ‘see [youth] as eye-openers to young people, and […] that the young people realize the hardship and the misuses by them’ (Interview PAN). Yet, traditional authorities and communities too, see the benefits of the work of youth organization. One interviewee stated, ‘[p]eople are seeing the need of peace, peace that is driven by people on desire’ (Interview Defender Peacebuilding Network). Consistent engagement in the communities and trust building as well as transparency and accountability show the positive impact of youth, which then leads to a supportive environment in communities. One interviewee explained that ‘you need to be patient with your work and not push too hard, as this will not lead anywhere’ (Interview G-Net). Therefore, organizations use inclusive approaches, where traditional and religious authorities, parents and teachers can participate equally (Interview PPASL).

On an individual level, youth face problems such as a lack of support from their families or organizations in continuing their education or furthering their career. The biggest challenges are finances and funding. Youth-led organizations rely heavily on volunteers (Simpson Citation2018), but often lack funding to pay their expenses. This means that youth are not able to support their families, wherefore they are pressured to stop volunteering and earn money instead (Interview CYPA-SL). Others feel bad asking family and friends for funding for their work, stating that ‘[w]hen you want to host an event and you ask family or friends for support, and they don’t give that support, it kind of feels very bad’ (Interview Future Leaders Initiative). Other volunteers reported that they invest their own resources and, thus, need to have side businesses, which require a lot of time and effort. This has led to a high fluctuance between youth organizations and other job sectors that look for the skills youth acquire during their volunteering and can afford to pay higher salaries (World Bank Citation2006).

4.3 Young people and their interactions with CSOs

Civil society organizations from the Global North are crucial for supporting the vision of youth in peacebuilding. They refer to the potential of young people, wanting to educate, empower, and work with them (Simpson Citation2018). This is also shown in our data. Most CSOs cooperate with international CSOs, with however mixed opinions. On the one hand, there are collegial relationships and partnerships with internationals, which is beneficial for learning experiences and high reputations in the communities, as ‘they really understand what is happening in Sierra Leone’ (Interview CPCS). On the other hand, international CSOs or CSOs from neighboring countries ‘[do not always] have good intervention mechanisms and just interrupt the existing system. For example, religion and culture play a huge role in mediation between parties […] and this is difficult for external actors’ (Interview GYNP). In this regard, it was mentioned that the international CSOs come with their own agendas and determine the conditions of the cooperation. It was questioned by some if this is then based on equal partnership: ‘certain organizations tell you that they deal with different partners and all are equal, but they are not. They do not trust local organizations, for example, with choosing topics or finances, and how can this then be a partnership’ (anonymous Interview). Another interviewee confirmed that, stating that ‘before donors bring their resources, they already have a plan what they want to do’ (Interview Jem’s Agro Business). This is problematic, as it does not empower the youth as local actors but can give them a feeling of being compromised. This is not uniqueto youth organizations, but a common phenomenon between local and international CSOs (Ruppel Citation2023). CSOs from the Global North that work with youth base their work on ideas or programmatic assumptions that are usually part of a larger peace agenda or a component of a program to reach target groups as broadly as possible (Kwon Citation2019).

Another issue is the high donor dependency of CSOs in Sierra Leone (Cubitt Citation2012). The lack of (financial) resources was pointed out in every interview and often defined as the number one challenge forcing CSOs to work in a very broad thematic field to address as many donors as possible (BadasiSesay Citation2012). Interviewees demanded that the government and international CSOs provide more funding to youth organizations, as they do not have other access points for it. ‘[Donors] bring funding and can make your organization grow. They can give you projects and programs to implement, so they keep your organization running’ (Interview YACAN). This corresponds with the barrier that youth lack the knowledge, network connections, or the status of a non-governmental organization sometimes required to apply for international funding. To mitigate these, many CSOs have joined national or international networks to have better and easier access to funding, training, and expertise. This has become a key strength of the sector (Kanyako Citation2011) and brings ideas together. ‘[Local CSOs] also have partners, […] so we learn from each other. I get to meet other managers and talk to them, discuss topics and exchange ideas’ (Interview CYPA-SL). While this sort of networking appears crucial, it was pointed out that such cooperation can get difficult when there is too much competition for funds or cooperation with external donors (Interview WAYN).

Some of the internal challenges of youth CSOs mentioned during our interviews are related to staff. In 2014, 15,472 people were employed by national or international CSOs, of which only 11.9% were international staff (Statistics Sierra Leone Citation2014). Staff recruitment mostly happens ad hoc and informally. This includes hiring staff with little professional expertise as most CSOs cannot afford to hire high-caliber staff or employ staff beyond the end of projects (USAID Citation2019). Other studies describe the opportunity to work in one of the CSOs as a very good chance to gain professional experience (Bolten Citation2014). As shown above, our interviewees reported that they work in the CSO sector mostly because of intrinsic motivation and for personal growth, yet ‘sometimes people only want to volunteer or work because they expect to get paid’ (Interview YACAN). A fact that can often lead to frustration and drop-outs as payment is not always provided. Some interviewees pointed out that it would be helpful to get funding to pay the project staff and not only the projects itself, so qualified young people would have a chance to stay in the organizations and sustain themselves. This corresponds with the general need of youth to find stable jobs and income in the economy of Sierra Leone (Enria Citation2015).

Youth-led CSOs also face challenges on an individual level. There have been repeated complaints that CSOs are corrupt, do not handle money well, or do not spend it in a targeted manner (Pemunta Citation2021). One interviewee mentioned that sometimes, they do not have any other choice as this is what the political situation in the country is demanding (anonymous interview). Others pointed out that this is also part of Sierra Leone’s society and not a problem inherent to CSOs. ‘For a lot of people, corruption is an integral part of the society, so it is difficult to change them’ (Interview WAYN). These accusations are certainly partly tenable but are also the result of misunderstandings between the CSOs and the local population, where communities, family, and friends assume that the funding for CSOs is much higher than it is. ‘Often they need money as a short-term benefit and expect this from us, there is the stereotypes that we have money’ (Interview YACAN).

Furthermore, CSOs in Sierra Leone experience a shrinking space (EU Citation2017): ‘Most young people [are] afraid to get out to raise their voices’ (Interview PPASL). CSOs that speak out against the government are labeled as part of the opposition (Interview YACAN), which hinders the work of the organizations. This problem of being seen as the opposition has to do with the general political dynamics as well as the history of the country. CSOs in Sierra Leone are restricted in their freedom rights (Freedom House Citation2020), and can no longer carry their work out freely. Some youths are even afraid to speak up because of the political situation in the country: ‘there are certain issues you want to talk about, and another person sees them as highly political, so we cannot speak really freely’ (Interview PPASL). The issue of shrinking spaces threatens the ability of youth to create everyday peace and thus realize bottom-up peacebuilding and raise voices of marginalized groups (Mac Ginty and Firchow Citation2016). Despite these challenges with the government, interviewees pointed out that there are also positive sides of working together with government agencies. Sometimes they provide funding, which is perceived as a form of advocacy. Others again see their own work as a support toward the government’ goals: ‘we all know that the government is working on this topic, but the government has so many parties, so we remind our government to work on education’ (Interview Education for All). Again, however, the collaborative work with the government must be aligned with the government’s political goals and viewpoints.

5. Conclusion

This paper presented the various perceptions on and by youth and their social commitment in Sierra Leone in form volunteering or working for local CSOs. We gave insights into different views on youth in conflicts and investigated the positive impacts of youth in peacebuilding. Our interviewees told us about their motivations and desires for a peaceful Sierra Leone, the work they do toward it, but also about their personal, cultural/social, and political challenges, and their experiences and opinions on cooperation with local and international CSOs. With their motivation and engagement, young people in Sierra Leone play an important role in everyday peace, as they locally thrive to contribute to the peacebuilding process in their country. Most interviewees we spoke with have the strong believe, that working toward peace in their own communities will lead to a more peaceful country on the long run, that will than build more and opportunities for a better future for them and the next generations. What might sound idealistic is already bearing fruits. Our interviews reported changes and shared success stories. Nevertheless, we discovered that although the Sierra Leonean war has been over for almost 20 years and the image of youth as mere violent actors has altered, youth still face many challenges and dilemmas in finding space to contribute meaningfully to a sustainable development. Youth employment and educational opportunities remain a challenge, and hierarchical structures in politics and within the society limit the space for socially committed youth. Many feel excluded and disadvantaged, yet they have proven resilient actors that use organizations to counter stereotypes and repressive structures. Being used by politicians for their own purposes, being marginalized and excluded does not undermine the youth’s peacebuilding work per se, but encourages youth to engage in CSOs (Pherali Citation2016). Our interview partners demonstrated a high level of motivation for a peaceful Sierra Leone, and to aim for more integration into social and political processes, where they can develop and flourish to become self-reliant and accepted members of society.

Due to their wide range of experiences, knowledge, and identities, young people receive increasing attention. On the one hand, this is demonstrated on a societal level, where interviewees reported positive developments and changes in the minds and behaviors of people and where youth receive more acceptance in their work. On the other hand, the importance of young people is visible in the work of international donors and the civil society mainly from the Global North. CSOs from the Global North refer to the potential of youth and focus programs increasingly on the education and empowerment of youth in post-conflict settings. However, many youths and their CSO still face structural challenges, like the lack of funding or shrinking spaces. Cooperation with other CSOs has likewise proven challenging when there is a high competition between local organizations or when international CSOs try to implement their own agendas without adequate consultation and cooperation with local organizations. This lack of funding as well as the glimpse of a funding opportunity from international CSOs often leaves young people and locally-led youth CSOs feeling dependent and sometimes compromised by the necessity to work with partners from the Global North. Our interviewees mentioned that they wish to work on other topics or with other methods but are bind to certain topics for example due to availability of funding. There is a high awareness of this dependencies as well as inherent power imbalances of the work between local and international CSOs (Ruppel Citation2021), yet our interviewees did not see a clear way out.

Our case study demonstrated that there is a strong desire of young people to change their image of being passive or violent and to become recognized and accepted members of their families, communities, and the political realm. Their social commitment is important not only for the future of youth in the country, but also for the future of politics and work of international organizations. Our interview partners want to actively contribute to the development of a peaceful nation and want to be driving forces of peace. Harvesting their skills and interests is, thus, crucial to fostering an empowered and encouraged youth and, thus, sustaining the peace in Sierra Leone. Therefore, on a macro level it will become important, that local actors do take youth seriously and at the same time, that international organizations are addressing power imbalances and dependencies together with the young people. With this paper, we contribute and add to previous research on youth agency by shedding light on their role in an everyday peace in Sierra Leone. Future research should consider the opportunity to further investigate the engagement of youth and their impact on their social environment and on the topic of overcoming power imbalances within cooperation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The UN Resolution 2250 defines youth of an age between 18 and 29 (UN Citation2015), the African Union between the ages of 14 and 35 (AU Citation2006), and the World Programme of Action for Youth between the ages 15 and 24 (UN Citation2010).

2 These are Children and Youth for Peace Agency Sierra Leone (CYPA-SL), Commission for Peace and National Cohesion (CPNC), Compassion for Peace and Child Survival (CPCS), Life for African Mothers Sierra Leone (LFAM-SL), Defenders Peacebuilding Network, Education for All (EFA), Future Leaders Initiative (FLI), Gender and Youth Network (GYN), Global Youth Network for Peace (GYNP), National Youth Commission (NAYCOM), Patriotic Advocacy Network (PAN), Planned Parenthood Association Sierra Leone (PPASL), Students Against Violence Everywhere Sierra Leone (SAVE-SL), Society for Learning and Yearning for Equal Opportunity (SLYEO), West African Youth Network (WAYN),Youth and Child Advocacy Network (YACAN), Youth Action for Self-Development Sierra Leone (YASDSL), Young Peacebuilders Initiative (YPI). Additionally, we spoke with some organizations to get some previous background information, but they are not part of this study, as they served as a preliminary discussion. These are: Advocacy Initiative for Development Sierra Leone (AID SL), Society for Learning and Yearning for Equal Opportunity (SLYEO), Network Movement for Youth and Children’s Welfare (NMYCW), Youth Action for Self-Development Sierra Leone (YASDSL), and Young Welfare and Development Organization (YWDO).

References

- Abdullah, I. 2004. “Bush Path To Destruction: The Origin and Character of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF/SL).” In Between Democracy and Terror: The Sierra Leone Civil War, edited by I. Abdullah, 41–65. Dakar: CODESRIA.

- Ackermann, L., T. Feeny, J. Hart, and J. Newman. 2003. Understanding and Evaluating Children’s Participation: A Review of Contemporary Literature. London: Plan International.

- Amambia, S., F. Bivens, M. Hamisi, I. Lancaster, O. Ogada, G. Okumu, N. Songora, and R. Zaid. 2018. Participatory Action Research for Advancing Youth-Led Peacebuilding in Kenya. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

- Anderson, M. 1999. Do No Harm: How Aid Can Support Peace - or War. Boulder/London: Lynne Rienner.

- AU. 2006. “African Youth Policy.” https://au.int/sites/default/files/treaties/7789-treaty-0033_-_african_youth_charter_e.pdf.

- BadasiSesay, A. 2012. Civil Society Organisations’ Cluster Engagement in Sierra Leone: The Rationale and Progress to Date. Freetown: UNIPSIL.

- Berents, H., and S. McEvoy-Levy. 2015. “Theorising Youth and Everyday Peace(Building).” Peacebuilding 3 (2): 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/21647259.2015.1052627.

- Berents, H., and C. Mollica. 2020. “Youth and Peacebuilding.” In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Peace and Conflict Studies, edited by O. Richmond, and G. Visoka, 1–16. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bolten, C. 2014. “Social Networks, Resources, and International NGOs in Postwar Sierra Leone.” African Conflict and Peacebuilding Review 4 (1): 33–59. https://doi.org/10.2979/africonfpeacrevi.4.1.33.

- Bolten, C. 2019. Serious Youth in Sierra Leone: An Ethnography of Performance and Global Connection. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Christensen, M., and M. Utas. 2008. “Mercenaries of Democracy: The ‘Politricks’ of Remobilized Combatants in the 2007 General Elections, Sierra Leone.”.” African Affairs 107/429 (5): 515–539. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adn057.

- Cohn, I., and G. Goodwin-Gill. 2003. Child Soldiers. The Role of Children in Armed Conflict. Oxford: Clarendon-Press.

- Cronin-Furman, K., and M. Lake. 2018. “Ethics Abroad: Fieldwork in Fragile and Violent Contexts.” American Political Science Association 51 (3): 607–614.

- Cubitt, C. 2012. Local and Global Dynamics of Peacebuilding. Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sierra Leone. London: Routledge.

- Del Felice, C., and A. Wisler. 2007. “The Unexplored Power and Potential of Youth as Peace-Builders.” Journal of Peace Conflict & Development 11: 1–29.

- Distler, W. 2019. “Dangerised Youth: The Politics of Security and Development in Timor-Leste.” Third World Quarterly 40 (4): 727–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1401924.

- Enria, Luisa. 2015. “Love and Betrayal.” The Political Economy of Youth Violence in Post-War Sierra Leone.”Journal of Modern African Studies 53 (4): 637–660.

- EU. 2017. “EU Roadmap for Engagement with Civil Society in Liberia.” https://europa.eu/capacity4dev/file/86370/download?token=N3BWRgMK.

- Ezemenaka, Kingsley Emeka. 2021. “Youth Violence and Human Security in Nigeria.” Social Sciences 10 (267): 1–17.

- Fanthorpe, R., and R. Maconachie. 2010. “Beyond the “Crisis of Youth”. Mining, Farming and Civil Society in Post-War Sierra Leone.” African Affairs 109 (435): 251–272. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adq004.

- Flinders, M., M. Wood, and M. Cunningham. 2016. “The Politics of co-Production: Risks, Limits and Pollution.” Evidence & Policy 12 (2): 261–279. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426415X14412037949967.

- Freedom House. 2020. “Freedom in the World 2020.” Sierra Leone: https://freedomhouse.org/country/sierra-leone/freedom-world/2020.

- Fujii, L. 2009. Killing Neighbors. Webs of Violence in Rwanda. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Goodhand, J. 2000. “Research in Conflict Zones – Ethics and Accountability.” Forced Migration Review 8: 12–15.

- Government of Sierra Leone. 2003. “Sierra Leone National Youth Policy.” https://www.youthpolicy.org/national/Sierra_Leone_2003_National_Youth_Policy.pdf.

- Haer, R. 2019. “Children and Armed Conflict: Looking at the Future and Learning from the Past.” Third World Quarterly 40 (1): 74–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2018.1552131.

- Hajjaj, O., and I. Mandysova. 2017. Soft Skills Importance in NGOs’ Positions. Koper: University of Primorska Press.

- Jackson, P. 2021. “Interview Locations.” In The Companion to Peace and Conflict Fieldwork, edited by R. Mac Ginty, R. Brett, and B. Vogel, 101–114. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jimenez, E., and M. Murthi. 2006. “Investing in the Youth Bulge.” Finance and Development 43 (3): 40–43.

- Kanyako, V. 2011. “The Check Is Not in the Mail: How Local Civil-Society Organizations Cope with Funding Volatility in Postconflict Sierra Leone.” Africa Today 28 (2): 2–16.

- Kasherwa, A. 2020. “The Role of Youth Organizations in Peacebuilding in the African Great Lakes Region: A Rough Transition from Local and non-Governmental to the National and Governmental Peacebuilding Efforts in Burundi and Eastern DRC.” Journal of Peace Education 17 (2): 123–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2019.1688139.

- Keen, D. 2003. “Greedy Elites, Dwindling Resources, Alienated Youths. The Anatomy of Protracted Violence in Sierra Leone.” InternationalePolitik und Gesellschaft 6 (2): 67–94.

- Kurtenbach, S. 2018. Changing the Status Quo - Youths as Actors for Peace. Hamburg: German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Leibniz-InstitutfürGlobale und RegionaleStudien.

- Kwon, S. A. 2019. “The Politics of Global Youth Participation.” Journal of Youth Studies 22 (7): 926–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2018.1559282.

- Lansana, G. 2005. A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and the Destruction of Sierra Leone. London: Hurst.

- Mac Ginty, R., and P. Firchow. 2016. “Top-down and Bottom-up Narratives of Peace and Conflict.” SAGE Publications 36 (3): 308–323.

- McEvoy-Levy, S. 2011. “Children, Youth and Peacebuilding.” In Critical Issues in Peace and Conflict Studies. Theory, Practice, and Pedagogy, edited by T. Matyók, J. Senehi, and S. Byrne, 159–176. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- McEvoy-Levy, S. 2012. “Youth Spaces in Haunted Places: Placemaking for Peacebuilding in Theory and Practice.” International Journal of Peace Studies 17 (2): 1–32.

- Mitton, K. 2009. “Reconstructing Trust in Sierra Leone.” The Round Table 98 (403): 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/00358530903018046.

- Mitton, K. 2013. “Where is the War? Explaining Peace in Sierra Leone.” International Peacekeeping 20 (3): 321–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/13533312.2013.838391.

- Murata, A., and N. Nishimura. 2016. Youth Employment and NGOs: Evidence from Bangladesh. Tokyo: JICA Research Institute.

- Nagel, C., and L. Staeheli. 2015. “International Donors, NGOs, and the Geopolitics of Youth Citizenship in Contemporary Lebanon.” Geopolitics 20 (2): 223–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.922958.

- Njoku, E. 2020. “Investigating the Intersections Between Counter-Terrorism and NGOs in Nigeria: Development Practice in Conflict-Affected Areas.” Development in Practice 30 (4): 501–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/09614524.2020.1714546.

- Özerdem, A., and S. Podder. 2015. Youth in Conflict and Peacebuilding. Mobilization, Reintegration and Reconciliation. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Park, A. 2006. “‘Other Inhumane Acts’: Forced Marriage, Girl Soldiers and the Special Court for Sierra Leone.” Social & Legal Studies 15 (3): 315–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663906066611.

- Parker, C., S. Scott, and A. Geddes. 2019. Snowball Sampling. Gloucestershire: SAGE Research Methods Foundations.

- Peace and Security Council fo the African Union. 2020. “A Study on the Roles and Contributions of Youth to Peace and Security in Africa.” http://afripol.peaceau.org/uploads/a-study-on-the-roles-and-contributions-of-youth-to-peace-and-security-in-africa-17-sept-2020.pdf.

- Pemunta, N. 2021. “Neoliberal Peace and the Development Deficit in Post-Conflict Sierra Leone.” International Journal of Development Issues 11 (3): 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1108/14468951211262242.

- Pherali, T. 2016. “Education: Cultural Reproduction, Revolution and Peacebuilding in Conflict-Affected Societies.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Disciplinary and Regional Approaches to Peace, edited by O. Richmond, S. Pogodda, and J. Ramović, 193–205. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pruitt, L. 2013. Youth Peacebuilding. Music, Gender, and Change. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Rashid, I. 2004. “Student Radicals, Lumpen Youth, and the Origins of Revolutionary Groups in Sierra Leone, 1977-1996.” In Between Democracy and Terror: The Sierra Leone Civil War, edited by I. Abdullah, 66–89. Dakar: CODESRIA.

- Richards, P. 1996. Fighting for the Rain Forest: War, Youth and Resources in Sierra Leone (African Issues). Portsmouth: Heinemann.

- Richards, P. 2005. “To Fight or to Farm? Agrarian Dimensions of the Mano River Conflicts (Liberia and Sierra Leone).” African Affairs 104 (417): 571–590. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adi068.

- Ruppel, S. 2020. “When Your Lab is the World but the World is Closed Down - Social Science Research in Times of Covid-19.”. Accessed March 30, 2022. https://elephantinthelab.org/when-your-lab-is-the-world-but-the-world-is-closed-down/.

- Ruppel, S. 2021. “Power Imbalances and Peace Building: A Participatory Approach Between Local and International Actors.” Africa Amani Journal 8: 1–29.

- Ruppel, S. 2023. LokalverankerteZivileKonfliktbearbeitungzwischenPartnerschaft und Machtungleichgewicht. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Schwartz, S. 2010. Youth and Post-Conflict Reconstruction. Agents of Change. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

- Shepler, S. 2005. “The Rites of the Child: Global Discourses of Youth and Reintegrating Child Soldiers in Sierra Leone.” Journal of Human Rights 4 (2): 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14754830590952143.

- Simpson, G. 2018. The Missing Peace: Independent Progress Study on Youth, Peace and Security. New York: United Nations Population Fund.

- Smith, A., and C. Smith Ellison. 2021. Youth, Education, and Peacebuilding. Coleraine: UNESCO Centre, University of Ulster.

- Statistics Sierra, Leone. 2014. “Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) Survey for National Accounts Compilation.” https://www.statistics.sl/images/StatisticsSL/Documents/Publications/2013/2013_ngo_survey_for_national_accounts_compilation.pdf.

- Tainturier, P. 2016. Youth Inclusion Through Civic Engagement in NGOs After the Tunisian Revolution. Rom: Power2Youth.

- Tom, P. 2014. “Youth-traditional Authorities’ Relations in Post-war Sierra Leone.” Children's Geographies 12 (3): 327–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2014.922679.

- UN. 2010. “World Programme of Action for Youth.” https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unyin/documents/wpay2010.pdf.

- UN. 2015. “S/RES/2250.” https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/413/06/PDF/N1541306.pdf.

- UN. 2019. World Population Prospects 2019. Highlights. New York: United Nations.

- UNDP. 2006. Youth and Violent Conflict. Society and Development in Crisis? New York: United Nations Development Programme.

- UNOY and Search for Common Ground. 2017. Mapping a Sector: Bridging the Evidence Gap on Youth-Driven Peacebuilding. The Hague: United Network of Young Peacebuilders.

- UN. Volunteers. 2017. “The Role of Youth Volunteerism in Sustaining Peace and Security.” https://www.youth4peace.info/system/files/2018-04/13.%20TP_Role%20of%20Youth%20Volunteerism%20in%20Sustaing%20Peace_UNV.pdf.

- USAID. 2019. Civil Society Organization Sustainability Index. For Sub-Saharan Africa. Washington DC: United States Agency for International Development.

- Waal, A. 2002. “Realising Child Rights in Africa: Children, Young People and Leadership.” In Young Africa: Realising the Rights of Children and Youth, edited by A. Waal, 1–28. Trenton: Africa World Press.

- Wilkinson, S. 1998. “Focus Groups in Feminist Research: Power, Interaction, and the Co-Construction of Meaning.” Women's Studies International Forum 21 (1): 111–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-5395(97)00080-0.

- World Bank. 2006. Economics and Governance of Nongovernmental Organizations in Bangladesh. Dhaka: The World Bank Office.

- Yea, S. 2018. “Helping From Home: Singaporean Youth Volunteers with Migrant-Rights and Human-Trafficking NGOs in Singapore.” The Geographical Journal 184 (2): 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12221.