ABSTRACT

The social and economic impacts of COVID-19 have been devastating for many, and collectively young people generally fared worse than older adults, with the impact amongst young people also being highly uneven. Most studies on this topic focus on Global North contexts, with experiences in the Global South being less well understood. Focusing on young people in Nepal and Indonesia who were especially exposed to the fallout from the pandemic (in part due to their occupations), this paper analyzes over 1400 weekly diary entries from 100 respondents written across four months in the first half of 2021. Participants recall increasingly precarious individual and family situations due to pandemic-related livelihood upheavals and insufficient access to social protection. Amongst diverse ‘coping strategies’, many turned to debt to smooth fluctuating incomes – leading to both financial and social obligations and forcing sometimes life-altering decisions such as leaving education and moving into risky work. Spiralling indebtedness may have consequences for livelihoods across young people’s life-courses; with futures mortgaged to survive precarity at the peak of the Delta wave of COVID-19. Looking ahead, policy makers should reconfigure disaster responses and social protection with a youth-lens to ensure a robust, fair and sustainable recovery from future crises, mitigating inter-generational scarring effects.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had devastating impacts on many young people’s (aged 15–29) lives and livelihoods. Contagious and sometimes deadly, the coronavirus spread quickly, leading to the announcement of a global pandemic in March 2020. In response many governments implemented various forms of lockdown, curfew and social distancing (WHO Citation2023). Measures to mitigate contagion dealt blows to both the supply- and the demand-sides of the labour market, with young people over-represented in the sectors hit hardest by the pandemic especially hospitality, tourism and garment/textile manufacturing (Lee, Schmidt-Klau, and Verick Citation2020; OECD Citation2021; Verick, Schmidt-Klau, and Lee Citation2022). Firms, particularly small- and medium-sized enterprises laid off large proportions of their workforce (OECD Citation2021), with younger workers commonly ‘last in, first out’ (ADB and ILO Citation2020). Schools and training institutions closed their doors and shifted online, often by government directive, putting learning out of reach for some and forcing constrained learning/earning choices for many (Li and Lalani Citation2020; MacDonald et al. Citation2023).

Pandemic-induced stresses on young people’s livelihoods have been broken down into three main dimensions: (1) layoffs due to economic downturn and recurrent societal lockdowns; (2) disruptions to education and training; and (3) complications in the transitions from school into the workforce (ILO Citation2020). The effects of COVID-19 have varied both geographically and between sub-groups of young people. According to projections by the International Labour Organisation (ILO), regional gross domestic product (GDP) in the Asia Pacific Region was 6% lower in 2022 than pre-pandemic predictions (ILO Citation2022c), and stagnation continued into 2023. Within the region, young people’s employment losses were especially severe, with youth employment declines of 8.9% compared to 2.3% among adult workers (ILO Citation2022c). The Asia Pacific region held half of the global increase in the number of young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) in 2020, with the highest rates in South Asia (30.9%) and South-East Asia (18.3%) (ILO Citation2022b; Citation2022c). In Indonesia alone this equated to 555,600 more young people not in or seeking work or formal qualification between 2019 and 2020 (ILO Citation2022b).

Based on previous environmental and economic disasters, it is expected that these effects will have potentially life-altering consequences. Past shocks, such as the 2008–2009 Global Financial Crisis, for instance, had both short- and longer-term repercussions for young people’s lives and livelihoods in ways that marked individual life-courses and shaped household finances for years (Junankar Citation2015; Verick, Schmidt-Klau, and Lee Citation2022). Almost all low- and middle-income countries have experienced more severe declines in economic growth since 2020 than during the ‘global’ financial crisis (Verick, Schmidt-Klau, and Lee Citation2022). In many trade-exposed Global South contexts, the magnitude and prolonged nature of the economic and social upheaval brought by COVID-19 mean that recovery is projected to be highly sectoral and socially unequal. Young people – especially marginalised young people – are likely to fall further behind (ILO Citation2022a). The pandemic has in this sense compounded the already precarious economic position of youth, relative to older workers.

Despite the complex impacts of the pandemic on the lives and livelihoods of young people, there is a little qualitative literature examining how the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19 have affected young people’s coping strategies and social roles in developing country contexts. This study builds on existing scholarship on COVID-19 disruptions to employment and income by focusing on young’s people’s use of debt to enable household survival during the peak of the pandemic and the potentially lasting consequences indebtedness may have for life-courses and futures. The overarching research question is how were young people in Nepal and Indonesia impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, and how did they respond?

The paper proceeds with a review of relevant literature on young people, life transitions and the impact of shocks upon the livelihoods and social roles of young people, especially focusing on the financial and social obligations created by debt. We then examine how concepts of vulnerability, resilience and structural disempowerment can help make sense of individual and community-level agency amid shocks and crises such as COVID-19. The diary methods used in this project are then described, followed by a discussion of how income disruptions among respondents, combined with insufficient social protection, led to accrual of financial and social debts that may shape their life-courses for years to come. We conclude by emphasising the on-going need for governments and other stakeholders to ensure inclusive policies and programmes which bolster the resilience of young people and their households to future crises.

Literature: young people and debt

Youthhood is a dynamic and fluid development stage in the lifecycle of ‘being’ and ‘becoming’ (Barford Citation2023; Sanderson Citation2019). Alongside shifts in personal independence, sexual health, and civic responsibility, transitioning into the labour market is a major feature of youth, where personal characteristics interact with wider societal structures to produce varied, highly contextualised and unequal opportunities and outcomes for young people (Huijsmans, Ansell, and Froerer Citation2021; Närvänen and Näsman Citation2004). Beyond increased competition within saturated labour markets, age-specific obstacles to finding work include lower access to social, financial and physical capital (Raju and Rajbhandary Citation2018). Young women encounter additional barriers, including greater household responsibilities, lower wages and an expectation to avoid work thought of as ‘male’. In South Asia, rather than moving from school to (paid) work, many women undergo a school to wife transition (where being a wife involves work) (Brockie, O’Higgins, and Elsheikhi, Citationforthcoming; Huijsmans Citation2016).

COVID-19 disrupted already challenging pathways into work for youth (Huijsmans Citation2016; O’Higgins Citation2017). Even prior to the pandemic, most young people globally worked informally, with precarious incomes and lacking social or legal protection (Barford, Coombe, and Proefke Citation2020; Sumberg et al. Citation2021). Indonesia and Nepal both report low wages and high levels of youth worker informality (over 46% in Indonesia and over 90% in Nepal pre-COVID-19), resulting in many young people entering the pandemic on low incomes, with minimal savings and neither social protection nor health insurance (CBSN Citation2019, 29; Maryati and Muslin Citation2023, 93). As young people transition to adulthood, structural economic factors and environmental change heighten vulnerability, often extending or compromising young people’s life transitions (Barford et al. Citation2021; Berzin Citation2010).

The socio-economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic broadly maps onto pre-existing patterns of inequality and disadvantage. Some young people’s experiences were aggravated by intersecting social constraints based on gender, LGBTQI+Footnote1 status and physical or mental disabilities (Halimatussadiah, Agriva, and Nuryakin Citation2014; ILO and ADB Citation2020; Pattinasarany Citation2019). Female disadvantage is often further entrenched during times of crisis, which can deepen the unequal distribution of household work and increase domestic violence (Upadhyay and Karki Citation2021). LGBTQI+ populations experience many forms of discrimination, harassment and inequality, which can influence ‘poor mental health, violence, and suicide’ as well as a greater tendency to experience food insecurity, homelessness and poverty (Salerno et al. Citation2020). In Nepal, little is known about these groups as it relates to their well-being, social inclusion or social protection during COVID-19. People with disabilities also face barriers across the life course, with research in Indonesia indicating how a lack of classroom adaptations and a fierce job market create specific barriers for young people with disabilities (Lessy, Kailani, and Jahidin Citation2021). In recognition of the uneven impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, which largely relate to pre-existing discrimination and disadvantage, this study intentionally engages young people who were especially exposed to the social and economic consequences of this pandemic.

Relating to the impacts of the pandemic on more vulnerable young people, the generational consequences of inadequate social assistance and political marginalisation are significant, in the sense that systemic policy, regulatory, and fiscal decisions predispose societies and economies to crises that disproportionately impact specific demographics, especially the young (Barford and Gray Citation2022; MacDonald et al. Citation2023; Verick, Schmidt-Klau, and Lee Citation2022). Vulnerability, the ‘state or condition of being weak or poorly defended’ (Arora et al. Citation2015), often stems from constrained resources and livelihood opportunities, such as minimal state support and exploitative work (Huijsmans, Ansell, and Froerer Citation2021). When available, government social protection can buffer people from the worst impacts of shocks and bolster resilience (Arora et al. Citation2015). Discussions of self-reliance and resilience, however, often implicitly responsibilise people and compel them to ‘pull themselves up’ from poverty while avoiding discussion of systemic exploitation (MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2013). Here we use vulnerability and resilience less as predominantly individualised concepts often associated with responsibility and blame for one’s own circumstances; but instead recognising the role of structural factors, including social, economic and political systems, in shaping capacity and agency (van Breda Citation2018). Understanding resilience as a multilevel process sets young people's agency within a wider context. This context includes access to social protection, which influences the risk of prolonged precarity.

In conditions of underemployment, minimal social protection and constrained fiscal space, all compounded by crisis, personal debt often becomes an alternative yet perverse ‘safety net’ (Guérin, d'Espallier, and Venkatasubramanian Citation2013). Perverse in the sense that while often smoothing consumption and income, indebtedness can become a root cause of new vulnerabilities including dispossession and poverty (Ramprasad Citation2019; Wickramasinghe and Fernando Citation2017). While financial solutions like interest-free loans are often promoted as a pathway to crisis recovery, debt and financialisation become a form of ‘cruel optimism’ in the absence of adequate state social safety nets (Berlant Citation2011). Indebtedness is relevant to this research, as many households in Indonesia and Nepal took on new loans during the COVID-19 pandemic. In Nepal, one bank’s loans rose seven-fold from mid-2020 to early 2021 (Upadhyay and Karki Citation2021). Meanwhile, loans to Nepali female entrepreneurs increased by over 936% in the year up to mid-June 2021 (Upadhyay and Karki Citation2021). In Indonesia, households borrowing for daily necessities doubled from 2020 to 2022 (UNICEF et al. Citation2022). This issue is ongoing: in Nepal, recent protests draw attention to predatory loan sharks charging interest rates of up to 60% a year (Timilsena Citation2022).

The recognition of debt as a pathway to dispossession is not new. Credit has historically been used as a ‘development tool’ in the Global South, both through sovereign flows of wealth indebting poorer countries to richer ones (Akram and Hamid Citation2022), and individual debt marketed as a solution for the economically poor (Shakya and Rankin Citation2008). Financial institutions in state, non-profit and private sectors aim to make credit more accessible to the poor by promoting small loans with adjustments such as lower collateral criteria (Berlant Citation2011; Huang Citation2020; Karim Citation2011). Though access to capital can jumpstart entrepreneurial activity, individuals receiving small loans nevertheless operate within unequal social and political contexts, and often struggle to conform to the strict requirements of financial institutions (Field et al. Citation2013; Shakya and Rankin Citation2008). Further, borrowers may not be financially literate and often face other constraints in accessing finance (Shankland, Hyson, and Barford Citation2022; Upadhyay and Karki Citation2021). Rather than empowering recipients, research in Bangladesh and Nepal has shown how waves of debt – characterised by predatory interest rates, physical violence to force repayment, and distortions of social capital – often result in further indebtedness and dispossession amongst low-income groups. The result is often enormous repayment burdens which distort life courses and erode community ties (Karim Citation2011).

From the vantage of formal credit, financial institutions in Indonesia and Nepal temporarily suspended or relaxed debt repayment at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, ostensibly with the aim of benefitting the businesses and households which were worst impacted. Interventions included offering subsidised interest rates, extending loan repayment periods or loosening foreclosure benchmarks (Reuters Citation2021; Upadhyay and Karki Citation2021). Yet given the high prevalence of informality, both in employment and lending practices, the impact of temporary pandemic debt moratoria on household financial health were partial and limited. Little is known about how young people specifically navigated vulnerability and resilience, including their thinking, feeling and decision-making amid (often-constrained) choices. Drawing upon diaries written by 100 young people in Indonesia and Nepal during the Delta wave of COVID-19, we explore the availability of social protection and the role of personal debt for young people during this crisis as a prism into livelihood adaptations during the peak of this pandemic.

Methods: diary research during a pandemic

At a time when mobility was restricted by lockdowns, and when face-to-face data collection became legally, ethically and medically strained, we turned to solicited diaries to gain insight into young people’s lives, experiences, and feelings (Meth Citation2003; Mueller et al. Citation2023). This qualitative, real-time approach allowed for a temporal record of events as they were experienced, complementing and extending quantitative studies which delineate the magnitude of certain COVID-19 impacts including missed education, unemployment, morbidity and mortality. Diaries allow us to glimpse and compare young people’s experiences and perspectives on the short and longer-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. A detailed account of our methods can be found in Mueller et al. Citation2023.

Diary entries (n = 1418) were collected between March and July of 2021, coinciding with the Delta wave of COVID-19. The participants were 100 economically disadvantaged people aged 18–28, living in Indonesia and Nepal,Footnote2 grouped into five clusters (): (1) young mothers, who are often carers so faced additional work (Nichols et al. Citation2020); (2) tourism workers out of work due to travel restrictions (Rai Citation2020); (3) waste pickers on low incomes and whose work requires mobility (Barford Citation2020); (4) health care workers whose workload and contagion risks increased during this pandemic (Szabo et al. Citation2020); and (5) chronically vulnerable populations – people living with disabilities who face additional barriers, in Indonesia (Halimatussadiah, Agriva, and Nuryakin Citation2014) and LGBTQI+ people who face identity-based discrimination, in Nepal (Salerno et al. Citation2020, ). Nepal and Indonesia were selected due to our regional focus on Asia and our in-country networks.

Table 1. Summary of research participants.

Diary prompts were structured into seven themes: events and activities of the past week; impacts of COVID-19 on livelihood; sources of hope and well-being; challenges; coping with difficulty; responses of others; and cluster-specific themes. Led by a team of academics and NGO researchers, the project engaged five local rapporteurs (or researchers) in each country, relying on their leadership from research conception to data collection, analysis and dissemination (Proefke and Barford Citation2023). National coordinators and local rapporteurs recruited and managed the research participants, leveraging local knowledge and networks. Rapporteurs also convened three discussion groups with each cluster during the data collection period, enabling researchers to ask follow-up questions in response to the diary entries.

Rapporteurs were the first to analyse diary entries. Rapporteurs also translated the diaries into English, with pseudonyms to protect participants’ identities. The technical team subsequently collated the rapporteurs’ codes, performed a second round of coding on Atlas.ti, and embarked upon cross-cluster, cross-country analyses. While using grounded theory to code young people’s experiences of the pandemic, we acknowledge that pre-existing ideas and the diary prompts influenced the data. This research followed the safeguarding policy of the implementing NGOs, Rutgers Indonesia and Restless Development, which covers fairness, risk, integrity, respect and safeguarding.

Findings: fractured livelihoods, indebted youth

The diaries show how the COVID-19 pandemic’s impacts on health, social interaction and economic conditions variously affected all groups of young people. For tourism workers and waste pickers, labour demand suddenly plummeted, and lockdowns prevented the mobility upon which their work relies. Meanwhile, young mothers’ and health professionals’ work increased, with rising demand for unpaid care and growing medical caseloads, in addition to new home-schooling routines (). This section summarises the youth livelihood disruptions catalysed by COVID-19 in Nepal and Indonesia, focusing on employment and school-to-work transitions. It then identifies the significant gaps in access to formal support schemes experienced by many respondents. This leads us to examine the often-constrained choices of young people seeking to sustain themselves and their families. In doing so, we identify a range of adaptation strategies undertaken by young people. Taking on debt was a frequent response to the gaps created by falling incomes and rising food prices. In what follows we explore the use of debt by young people whose families lost work, while facing rising costs and scarcity of food and fuel, in addition to the COVID-19 health emergency.

Table 2. Young clusters and COVID-19 labour disruptions.

Disrupted incomes

Young people experienced significant livelihood disruptions and many lost work during the pandemic period. sets out the main disruptions to livelihoods faced by the five clusters of diarists. Informal workers saw their work and income ebb and flow with successive waves of COVID-19 and related restrictions. For most participants, this occurred against a backdrop of minimal social protection, limited savings and few formal entitlements. For participants without other income sources and minimal financial buffers, any period without work had consequences for them and their families. Informal workers often had to make trade-offs, for instance between paying for food or rent, or whether to work – risking contracting COVID-19 – or stay home without income. Meanwhile, participants who were formally employed experienced shifts in demand, with working hours spiking for health workers, and flat lining for tourism workers. Most formal sector workers were cushioned, financially by savings or family, and legally by their employee entitlements.

Given young people’s contributions to household incomes in Indonesia and Nepal, disruptions to young people’s earnings translated into wider household impacts. Many respondents recounted their struggles to perform their family responsibilities, such as covering siblings’ school fees, paying debts and doing household chores. These effects were highly gendered, with young female respondents performing most of the care and domestic work, which reduced their availability for paid work, especially as social distancing rules undermined the shared childcare arrangements which could have lessened this time commitment.

Patchy social protection

Few young diarists reported access to formal social protection during COVID-19, many were forced to turn to credit. Of the 100 participants, 52 mentioned receiving state support at some point during the diary writing period. Given that respondents were recruited from vulnerable populations from households likely to be living in poverty,Footnote3 this indicates low coverage amongst some of the subgroups most exposed to the socio-economic impacts of COVID-19. Most assistance received was short-term, such as one-off food aid, rather than sustained support over several months ().The number of diarists receiving social protection directly, on an individualised basis, rather than indirectly via their household, was lower still. Examples of support include the Nepali local government Unconditional Food Support and the Indonesian Family Hope Programme which provides cash transfers and food assistance to families. Both typically offered one-off support, and the Indonesian Family Hope Programme was targeted towards older adults. Exclusion from state social protection was most pronounced amongst young people with little knowledge of or connection to government initiatives, as highlighted below:

None in our family works as a civil servant. My husband and I are entrepreneurs; thus, we do not get any social protection from the government. (Young Mother, Urban Female, Age 28, Indonesia [10 April 2021])

The impossible thing that I might hope for right now is cash assistance. I hope someone will understand our distress cry. (Tourism Worker, Urban Other Gender, Age 22, Indonesia [16 April 2021])

Table 3. Formal support programmes.

Coping strategies

Faced with these constraints, many young diarists described diverse livelihood adaptations. These included starting small home-based businesses including selling vegetables, engaging in digital or online work including gaming and investment. Some respondents, especially LGBTIQ+ diarists and less commonly trekkers and tourism workers, also turned to sex work. Young mothers described using social media to learn new potentially profitable skills such as sewing, or breaking traditional taboos such as working on religious holidays.

Creating an alternative income stream was particularly important for informal workers, many of whom experienced a ‘stop-start’ state of work during early to mid 2021, depending on prevailing levels of pandemic restrictions and social and economic freedoms. This is demonstrated through the story of a young Nepali mother. Pre-pandemic, Radha worked informally, cleaning 5–7 houses per week. Like many young Nepali men, her husband had worked abroad but this ceased during the pandemic. Radha’s caring responsibilities then increased while her work was disrupted during COVID-19. Her child suffered illnesses, home-schooling began, there was a death in the family, and food and fuel were scarce. Radha’s cleaning work varied weekly, in line with her employers’ willingness to have her in their domestic space given the contagiousness of COVID-19. Radha started growing vegetables for family consumption and sale. Her diary entries demonstrate the precarious nature of informal work, and the tendency for people to diversify to other livelihood activities. She describes how ‘there was scarcity of food for children due to lack of money’ (27 March 2021). By the final week of diary writing, 10 July 2021, Radha was cleaning again, but her income remained exposed to the fluctuating pandemic and associated movement restrictions.

Reduced incomes and the absence of adequate and ongoing social support during the pandemic also led respondents to turn to their own networks for additional support. Many young people described how their household relied on informal reciprocity with neighbours. The most commonly mentioned coping strategy was taking on new debts to bridge gaps. We now turn to this in detail.

New debts

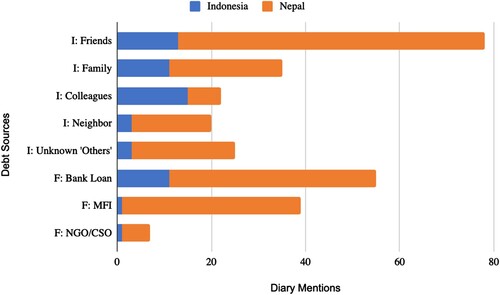

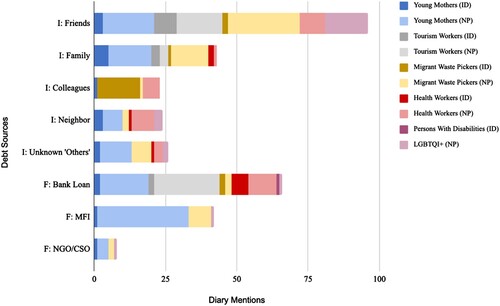

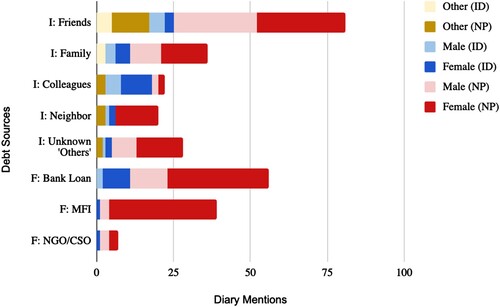

The absence of social protection stands in stark contrast to the apparent availability of formal and informal credit. Young people wrote repeatedly that financial security was a pressing priority, due to the immediate costs of food, rent and clothing for themselves and their families. Insufficient state social protection, combined with disrupted earnings, working-hour losses and the cost of meeting basic needs, led many to rely on formal and informal debt to sustain them during the pandemic. show the formal and informal debt diarists took on and were continuing to pay off during the Delta wave of COVID-19. While not a representative or generalisable sample, it is nevertheless instructive to examine patterns of debt by country, work, gender and to whom respondents are indebted. Overall, informal borrowing was an especially important source of support for young people, far more than from banks, microfinance institutions (MFIs), non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or civil society organisations (CSOs).

Figure 1. Sources of formal and informal credit by country.

Note: F = formal, I = informal. Nepal participants borrowed more than Indonesia participants; overall informal borrowing was used more than formal.

Figure 2. Sources of formal and informal debt, by sub-group.

Note: F = formal, I = informal. The LGBTQI+ cluster borrowed the least in Nepal and PwD the least in Indonesia; Young Mothers in Nepal borrowed the most.

Figure 3. Sources of formal and informal debt, by gender.

Note: F = formal, I = informal. Across genders, borrowing from friends was most common, followed by bank loans. Non-binary participants took no formal loans; women borrowed more than men.

Informal loans were primarily taken from friends, followed by family, colleagues and neighbours, and then others. The reasons for taking on new debt were overwhelmingly related to meeting daily needs, including rent, food and cooking fuel. This finding reflects research on household income across Asia in the wake of the pandemic which found that more than a third (38%) of respondents to national surveys had borrowed from family and friends during the COVID-19 pandemic, and most (80%) had reduced their food intake (Morgan and Trinh Citation2021, 17; Sitko et al. Citation2022). Diary respondents in Nepal and Indonesia emphasised the burden of borrowing, especially from close social relations.

… if lockdown hadn’t happened, we wouldn’t have to take the loan and would have been able to make more savings. But still many problems are there due to lockdown. To fulfil family expenses and with the economic crisis due to lockdown we were compelled to take a loan. Now it’s difficult to manage everything. (Young Mother, Rural Female, Age 21, Nepal [10 April 2021])

Sometimes I borrow money from the boss or take on debt for food when I don’t have any money. (Migrant Waste Picker, Urban Female, Age 20, Indonesia [16 April 2021])

I paid Rs.12,000 in rent to my landlord on the 10th of the month, the day I received my salary. I also spent Rs.19,000 to pay back the loan I took from local people to construct a house in my village. The remaining Rs.3,000 was spent on food shops while Rs 2,000 was saved for buying rice and gas. (Migrant Waste Picker, Urban Male, Age 27, Nepal [3 April 2021])

Finding credit, navigating debt

Young people’s diaries shed light on understandings of the financial risks and opportunities afforded by debt and borrowing – what may be termed their ‘financial literacy’. Many participants described how the burden of indebtedness caused them hardship. In Nepal, especially in rural areas, participants described a juggle to ‘pay interest’. Few respondents shared details of the interest rates they paid or financial calculations about repayment, perhaps suggesting a reluctance or sense of shame to share the details of their financial situation with the rapporteurs to whom they submitted their diaries. Only one diarist specifically mentioned the rate of interest they paid on a loan: an urban young mother from Nepal with some secondary education. She wrote: ‘I have taken Rs.100,000 [US$862 in 2021] as a loan on 36% interest which has been difficult to pay back due to lockdown’ (29 May 2021, Young Mother, Nepal). None of the diarists discussed inflation in relation to their borrowing, indicating that spikes in the price of food and basic household costs during the pandemic were more important determinants of their borrowing behaviour than of how inflation eroded the real value of the amount they owed.

Diarists described diversifying their indebtedness, for better or for worse, through three behaviours: borrowing from multiple sources, investing, and participating in cooperative loans. Although borrowing from multiple sources spreads debt across market and interpersonal loans, in this study the motivation for taking on multiple loans was typically to repay an earlier loan. Thus multi-borrowing highlighted the compounding problem of debt for respondents, which was more common in Nepal than in Indonesia. Diary entries show that for double borrowing, the first loan was often from a bank; with subsequent borrowing from family, friend networks and colleagues to make repayments to the formal financial institutions whose terms of repayment tended to be more rigid relative to the flexibility of more intimate family and social relations who tended to charge higher rates.

I was unable to pay the interest of the bank loan this time so I took out a loan from a friend. (Trekking Guide, Rural Female, Age 24, Nepal [10 July 2021])

So this week my relative borrowed money from me, to pay instalments to the bank. (Healthcare Worker, Rural Male, Age 28, Indonesia [21 May 2021])

I also had to pay the interests on the loan last week which I had to solve by asking everyone for help. (Migrant Waste Picker, Rural Male, Age 28, Nepal [3 April 2021])

… I have a problem with a member of my family who used to have a cooperative. With this jobless situation, now every month I have to pay [her] debt. [She] used my name to borrow money from the bank and now what happened, I have to take responsibility for everything. [She] is so crazy. How could I find money to pay off that debt? (Tourism Worker, Rural Female, Age 25, Indonesia [23 April 2021])

… actually I feel ashamed to have to borrow money from my neighbour, because the money that I got from the government was used up to buy milk and pay my debt to my brother/sister-in-law. (Young Mother, Rural Female, Age 28, Indonesia [16 April 2021])

Discussion: agency, precarity and post-pandemic life-courses

In addition to the disruptions to schooling and education brought on by pandemic restrictions, early transitions into the labour market are formative for young people’s future employment prospects. Being inactive or in unstable work is likely to increase the risk of disrupted career pathways in later transitions (Nilsen and Reiso Citation2014; Stuth and Jahn Citation2020). Disrupted livelihoods and the inadequacy of safety nets during the peak of COVID-19 drove many young participants and their households to make livelihood adaptations. In some cases these boosted their capacity to make ends meet in the short-term but also came at the cost of borrowing against their future lives and livelihoods.

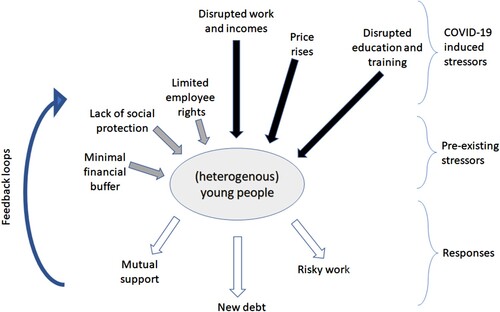

Certain 'adaptation' choices during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic did indeed translate into permanent losses of possibilities or resources, including through exposure to violence or disease. Many who dropped out of schooling or training during COVID-19 to make payments on old and new debts may indeed face constrained earnings across their life-course as a result of being less qualified. The effects on young people could have broader impacts on the structure of labour markets, distorting socio-economic development for years to come (O’Higgins Citation2017, v; O'Higgins et al. Citation2023). As depicted in , the outcomes for young people are shaped by a web of stressors, actors, institutions and resources that often pre-existed COVID-19, including poor employment rights and limited formal social protection.

Figure 4. Model of the stressors and responses of young people. Many stressors acting upon young people preceded COVID-19, pre-disposing them to pandemic shocks. Black arrows denote COVID-19-induced stressors. This model refers to the main observations from this study. Stressors and responses interact, sometimes compounding one another.

Income reductions experienced by diarists during the pandemic layered onto older forms of structural disadvantage. Reduced or unpredictable earnings, especially for those in informal and precarious work, added to economic and mental pressures. Coupled with patchy state support, income disruptions led some young people to take out new loans, while also adopting new income generating activities. Though many development paradigms present debt as a way for poor people to ‘enterprise themselves out of poverty’ (Schittway Citation2011), formal and informal debt can lead to oppressive and even violent outcomes (Huang Citation2020, 146; Karim Citation2011). The growth of debt and borrowing during the pandemic sparks concern about the capacity of underprotected and over indebted groups to recover, raising questions about the longer-term consequences across the life-course for young people and their households that accrue significant (formal and informal) debts.

Despite young people’s exclusion from government social initiatives before and during the pandemic (ILO and ADB Citation2020, 13–15), and the difficult trade-offs between finding work and incurring new debt, diarists attempted to take action to protect themselves. Some adopted dubious coping strategies which generated income but increased personal risk to themselves, for example breaching mobility restrictions or taking on risky work that carried a high chance of COVID-19 exposure. These decisions were constrained by scarce resources, sometimes resulting in riskier coping strategies. Other responses included safer livelihood activities, such as growing vegetables to sell despite limited local market demand. The improvisation and shifting of roles exhibited by young people enabled individual and family survival, albeit with concurrently growing debt.

Young people’s adaptations to adversity should not be used to justify further state social withdrawal (after MacKinnon and Derickson Citation2013). Indeed, partial and inadequate social safety nets contribute to spiralling personal debt among young respondents. Income precarity and debt accrual clearly alter young people’s choices – regarding education, training and work – in ways which impact how households and societies emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic. This is because past, current and future choices are shaped by debt obligations accrued during the pandemic. While many conceptualisations of youth concern the increased independence of young people in their families (Närvänen and Näsman Citation2004), the diary data highlight the extent to which many young people became livelihood lynchpins for their households and communities. Thus, as others have suggested, experiences during the pandemic could result in shifting conceptions of social and chronological age characteristics amongst the generation of young people who navigated the pandemic by managing complex webs of social relations, interdependencies and obligations (Punch Citation2015).

Conclusion

This research adds to a growing scholarship on how young people are impacted by COVID-19 (e.g. Porter et al. Citation2022), and contributes to understanding the damaging-but-necessary ‘coping’ strategies young people in Global South contexts adopted during COVID-19 (Subramanian Citation2021). Much scholarship on COVID-19 and young people focuses on high income countries; this paper responds to this geographical imbalance with an analysis of the diaries of 100 participants aged 18–28 from Indonesia and Nepal. Further, this granular qualitative study complements existing statistical descriptions of the constrained choices and experiences of young people in both contexts. Respondents’ diaries offer rich, personal insights into the unfolding experiences of young people at a time of immense disruption and upheaval. In particular, COVID-19 impacted youth people by increasing social isolation, halting education and reducing work; resulting in new care and financial burdens which have proved durable in spite of COVID-19 becoming less lethal and somewhat less prevalent.

Our diary research has shed light on areas for urgent youth-focused interventions in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous crises and recessions have had pronounced scarring effects on young people’s future lives due to shocks as they start to build their adult lives (Junankar Citation2015). Our research emphasises how a mortgaging of future lives and livelihoods during the peak of the pandemic compels the need for systemic action to promote youth empowerment by improving social safety nets and addressing spiralling household indebtedness coming out of COVID-19. Specifically, young people’s access to social protection should be reviewed to ensure coverage proportionate to needs and responsibilities.

Many research participants, in Nepal and Indonesia, played significant if not primary roles as earners in their household but received little social assistance during the Delta wave of COVID-19. Examining of weekly diaries found that disadvantaged young people took on new debts to survive this pandemic. In light of this, a ‘youth lens’ on social protection is necessary that takes seriously how structural and acute crises of livelihood can be mitigated in ways that enable young people to juggle their aspirations and obligations without being forced into decisions and coping strategies that constrain their future choices. We are not necessarily proposing youth-only social protection measures. Rather, we argue for expanding the scope of existing schemes such as targeted direct cash transfer programmes for low earners to include young people given their household responsibilities (Bastagli et al. Citation2019; Razavi et al. Citation2020, 58), as a step towards universal social protection (ILO Citation2021). These interventions would be most effective alongside policies which tackle predatory financialisation, including creating reasonable caps on interest rates and establishing regulations forgiving obviously exploitative or unsustainable loans as a way to enable household-level and society-wide recovery. Expanding financial literacy programmes may also equip young people struggling with multiple borrowing.

Finally, this study highlights how deep engagement with the lives and livelihoods of young people opens up new ways of seeing and conceptualising the barriers to stable, decent livelihoods – especially in low and medium-income contexts. Urgent policy interventions are clearly needed to strengthen social safety nets and reduce household indebtedness coming out of the pandemic. If societies are to emerge robust, fair and sustainable from COVID-19, and other crises, then the young people whose lives have been defined by pandemic, economic upheaval and climate crisis must no longer be forced to mortgage their futures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and intersex +.

2 The Poverty Probability Index (PPI) cut-offs: 48 for Indonesia, 59 for Nepal. Our working definition of youth is aged 15–29 and diarists fell within this range. Data collection ran 23 March 2021 to 10 July 2021 in Nepal; 6 April 2021 to 2 July 2021 in Indonesia.

3 Most respondents probably lived on <$2.50/day (Indonesia 80%, Nepal 58%).

References

- Akram, N., and A. Hamid. 2022. “Public Debt, Income Inequality and Macroeconomic Policies: Evidence from South Asian Countries.” Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences 36 (1): 99–108. http://pjss.bzu.edu.pk/index.php/pjss/article/view/396.

- Arora, S. K., D. Shah, S. Chaturvedi, and P. Gupta. 2015. “Defining and Measuring Vulnerability in Young People.” Indian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive & Social Medicine 40 (3): 193–197.

- Barford, A. 2020. “Informal Work in a Circular Economy: Waste Collection, Insecurity and COVID 19.” In Proceedings of the IS4CE2020 Conference. https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.56175.

- Barford, A. 2023. “Youth Futures Under Construction.” Journal of the British Academy 11 (s3): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/011s3.003.

- Barford, A., R. Coombe, and R. Proefke. 2020. “Youth Experiences of the Decent Work Deficit.” Geography 105 (2): 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167487.2020.12094090.

- Barford, A., and M. Gray. 2022. “The Tattered State: Falling Through the Social Safety Net.” Geoforum 137:115–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2022.09.020.

- Barford, A., A. Mugeere, R. Proefke, and B. Stocking. 2021. Young People and Climate Change, 1–17. The British Academy. https://doi.org/10.5871/bacop26/9780856726606.001.

- Bastagli, F., J. Hagen-Zanker, L. Harman, V. Barca, G. Sturge, and T. Schmidt. 2019. “The Impact of Cash Transfers.” Journal of Social Policy 48 (3): 569–594. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279418000715.

- Berlant, L. 2011. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Berzin, S. C. 2010. “Vulnerability in the Transition to Adulthood.” Children and Youth Services Review 32 (4): 487–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.11.001.

- Brockie, K., N. O’Higgins, and A. Elsheikhi. Forthcoming. NEET Isn’t Working? Characteristics of Young People not in Employment, Education or Training in South Asia. ILO Working Paper Series.

- CBSN. 2019. Report on the Nepal Labour Force Survey 2017/2018. National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics. https://nepalindata.com/media/resources/items/20/bNLFS-III_Final-Report.pdf.

- Field, E., R. Pande, J. Papp, and N. Rigol. 2013. “Does the Classic Microfinance Model Discourage Entrepreneurship among the Poor? Experimental Evidence from India.” American Economic Review 103 (6): 2196–2226. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2196.

- Guérin, I., B. d'Espallier, and G. Venkatasubramanian. 2013. “Debt in Rural South India: Fragmentation, Social Regulation and Discrimination.” The Journal of Development Studies 49 (9): 1155–1171. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2012.720365.

- Halimatussadiah, A., M. Agriva, and C. Nuryakin. 2014. Persons with Disabilities (PWD) and Labor Force in Indonesia. LPEM-FEIU. https://www.lpem.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/WP-LPEM_03_Alin.pdf.

- Huang, J. Q. 2020. To be an Entrepreneur. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Huijsmans, R. 2016. Generationing Development: A Relational Approach to Children, Youth and Development. London: Springer.

- Huijsmans, R., N. Ansell, and P. Froerer. 2021. “Introduction: Development, Young People, and the Social Production of Aspirations.” The European Journal of Development Research 33 (1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41287-020-00337-1.

- ILO. 2020. Preventing Exclusion from the Labour Market: Tackling the COVID-19 Youth Employment Crisis. Geneva: ILO.

- ILO. 2021. World Social Protection Report 2020-22, 1–315. Geneva: International Labour Organization. wcms_817572.pdf (ilo.org).

- ILO. 2022a. Sectoral Impact, Responses and Recommendations. Accessed June 19, 2022. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/coronavirus/sectoral/lang–en/index.htm.

- ILO. 2022b. Youth not in Employment, Education or Training in Asia and the Pacific: Trends and Policy Considerations. International Labour Organisation. ISBN:9789220379165. https://www.ilo.org/asia/publications/WCMS_860568/lang–en/index.htm.

- ILO. 2022c. Asia–Pacific Employment and Social Outlook 2022. Rethinking Sectoral Strategies for a Human-Centred Future of Work. ISBN: 9789220381472. https://doi.org/10.54394/EQNI6264.

- ILO and ADB. 2020. Tackling the COVID-19 Youth Employment Crisis in Asia and the Pacific. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—asia/—ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_753369.pdf.

- Junankar, P. 2015. “The Impact of the Global Financial Crisis on Youth Unemployment.” Economic and Labour Relations Review 26 (2): 191–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304615580536.

- Karim, L. 2011. Microfinance and Its Discontents. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lee, S., D. Schmidt-Klau, and S. Verick. 2020. “The Labour Market Impacts of the COVID-19: A Global Perspective.” The Indian Journal of Labour Economics 63 (S1): 11–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41027-020-00249-y.

- Lessy, Z., N. Kailani, and A. Jahidin. 2021. “Barriers to Employment as Experienced by Disabled University Graduates in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.” Asian Social Work and Policy Review 15 (2): 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1111/aswp.12226.

- Li, C., and F. Lalani. 2020. “The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed Education Forever.” World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/.

- MacDonald, R., H. King, E. Murphy, and W. Gill. 2023. “The COVID-19 Pandemic and Youth in Recent, Historical Perspective: More Pressure, More Precarity.” Journal of Youth Studies 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2022.2163884.

- MacKinnon, D., and K. D. Derickson. 2013. “From Resilience to Resourcefulness.” Progress in Human Geography 37 (2): 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512454775.

- Maryati, S., and I. Muslin. 2023. “The Characteristics of Young Employment in Indonesia: The Challenges of the Demographic Bonus Era.” International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Innovation 12 (1): 90–97. https://doi.org/10.35629/7722-12019097.

- Meth, P. 2003. “Entries and Omissions: Using Solicited Diaries in Geographical Research.” Area 35 (2): 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4762.00263.

- Morgan, P. J., and L. Q. Trinh. 2021. “Impacts of COVID-19 on Households in ASEAN Countries and Their Implications for Human Capital Development.” In ADBI Working Paper 1226, 1–30. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute. https://www.adb.org/publications/impactscovid-19-households-asean-countries.

- Mueller, G., A. Barford, H. Osborne, K. Pradhan, R. Proefke, S. Shrestha, and A. M. Pratiwi. 2023. “Disaster Diaries: Qualitative Research at a Distance.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 22. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221147163.

- Närvänen, A.-L., and E. Näsman. 2004. “Childhood as Generation or Life Phase?” Young 12 (1): 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308804039637.

- Nichols, C. E., F. Jalali, S. S. Ali, D. Gupta, S. Shrestha, and H. Fischer. 2020. “The Gendered Impacts of COVID-19 Amid Agrarian Distress.” Politics & Gender 16 (4): 1142–1149. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X20000483.

- Nilsen, Ø., and K. Reiso. 2014. “Scarring Effects of Early-Career Unemployment.” Nordic Economic Policy Review 1:13–46.

- OECD. 2021. Designing Active Labour Market Policies for the Recovery. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref = 1100_1100299-wthqhe00pu&title = Designing-active-labour-market-policies-for-the-recovery.

- O’Higgins, N. 2017. Rising to the Youth Employment Challenge. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- O’higgins, N., A. Barford, A. Coutts, A. Elsheikhi, L. Caro, and K. Brockie. 2023. “How NEET are Developing and Emerging Economies? What Do We Know and What Can be Done About It?” In Global Employment Policy Review 2023: Macroeconomic Policies for Recovery and Structural Transformation, 53–81. Geneva: International Labour Office. wcms_882222.pdf (ilo.org).

- Pattinasarany, I. R. I. 2019. “Not in Employment, Education or Training (NEET) Among the Youth in Indonesia.” MASYARAKAT: JurnalSosiologi 24 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.7454/mjs.v24i1.10308.

- Porter, C., A. Annina Hittmeyer, M. Favara, D. Scott, and A. Sánchez. 2022. “The Evolution of Young People’s Mental Health During COVID-19 and the Role of Food Insecurity.” Public Health in Practice 3:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhip.2022.100232.

- Proefke, R., and A. Barford. 2023. “Creating Spaces for Co-Research.” Journal of the British Academy 11 (s3): 19–42. https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/011s3.019.

- Punch, S. 2015. “Youth Transitions and Migration.” Journal of Youth Studies 18 (2): 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2014.944118.

- Rai, S. 2020. “Lives of Tourism Workforce in Nepal and the Pandemic.” International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change 14 (6): 182–195.

- Raju, D., and J. Rajbhandary. 2018. Youth Employment in Nepal. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1276-7.

- Ramprasad, V. 2019. “Debt and Vulnerability: Indebtedness, Institutions and Smallholder Agriculture in South India.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (6): 1286–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2018.1460597.

- Razavi, S., C. Behrendt, M. Bierbaum, I. Orton, and L. Tessier. 2020. “Reinvigorating the Social Contract and Strengthening Social Cohesion.” International Social Security Review 73 (3): 55–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/issr.12245.

- Reuters. 2021. “Pandemic-Hit Indonesian Borrowers to Gain Extension of Credit Relief Rules Until 2023.” https://www.reuters.com/article/indonesia-banks-idUKL1N2Q5033.

- Salerno, J. P., J. Devadas, M. Pease, B. Nketia, and J. N. Fish. 2020. “Sexual and Gender Minority Stress Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Public Health Reports 135 (6): 721–727. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354920954511.

- Sanderson, E. 2019. “Youth Transitions to Employment: Longitudinal Evidence from Marginalised Young People in England.” Journal of Youth Studies 23 (10): 1310–1329. 10.1080/13676261.2019.1671581.

- Schwittay, A. F. 2011. “The Financial Inclusion Assemblage: Subjects, Technics and Rationalities.” Critique of Anthropology 31 (4): 381–401.

- Shakya, Y. B., and K. N. Rankin. 2008. “The Politics of Subversion in Development Practice: An Exploration of Microfinance in Nepal and Vietnam.” The Journal of Development Studies 44 (8): 1214–1235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380802242461.

- Shankland, S., K. Hyson, and A. Barford. 2022. Lifting Youth Participation Through Financial Inclusion, 1–76. Business Fights Poverty and Murray Edwards College.

- Sitko, N., M. Knowles, F. Viberti, and D. Bordi. 2022. Assessing the Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Livelihoods of Rural People. Rome: FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb7672en.

- Stuth, S., and K. Jahn. 2020. “Young, Successful, Precarious?” Journal of Youth Studies 23 (6): 702–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1636945.

- Subramanian, R. R. 2021. Youth-Led Action Research on the Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Marginalised Youth. Asia South Pacific Association for Basic and Adult Education. https://vital.voced.edu.au/vital/access/services/Download/ngv:91071/SOURCE2.

- Sumberg, J., L. Fox, J. Flynn, P. Mader, and M. Oosterom. 2021. “Africa’s “Youth Employment” Crisis is Actually a “Missing Jobs” Crisis.” Development Policy Review 39 (4): 621–643. http://doi.org/10.1111/dpr.v39.4.

- Szabo, S., A. Nove, Z. Matthews, A. Bajracharya, I. Dhillon, D. R. Singh, A. Saares, and J. Campbell. 2020. “Health Workforce Demography: A Framework to Improve Understanding of the Health Workforce and Support Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.” Human Resources for Health 18 (1): 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-0445-6.

- Timilsena, P. C. 2022. “Bitten by Loan Sharks, Seeking Cure in Capital.” Kathmandu Post, August 20. https://kathmandupost.com/visual-stories/2022/08/20/bitten-by-loan-sharks-seeking-cure-in-capital.

- UNICEF, UNDP, Prospera, and SMERU. 2022. The Social and Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Households in Indonesia: A Second Round of Surveys in 2022, Jakarta, Indonesia. https://www.unicef.org/indonesia/media/15441/file/The%20social%20and%20economic%20impact%20of%20COVID-19%20on%20households%20in%20Indonesia%20.pdf.

- Upadhyay, A., and S. Karki. 2021. “Covid, Women, and Debt in Nepal.” The Asia Foundation, September 1. https://asiafoundation.org/2021/09/01/covid-women-and-debt-in-nepal/.

- van Breda, A. D. 2018. “A Critical Review of Resilience Theory and Its Relevance for Social Work.” Social Work 54 (1): 1–18.

- Verick, S., D. Schmidt-Klau, and S. Lee. 2022. “Is This Time Really Different? How the Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis on Labour Markets Contrasts with That of the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–09.” International Labour Review 161 (1): 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/ilr.12230.

- WHO. 2023. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic. Geneva: World Health Organisation. Accessed April 1, 2023. https://www.who.int/europe/emergencies/situations/covid-19.

- Wickramasinghe, V., and D. Fernando. 2017. “Use of Microcredit for Household Income and Consumption Smoothing by Low Income Communities.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 41 (6): 647–658. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12378.