ABSTRACT

Providing employment to nationals in an economy where more than two-thirds of the population comprise foreigners has been a struggle for the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Of the various tactics used by the GCC countries to nationalize their workforce, the quota system policy has been the most popular one. This study examines the integrative scholarly research on the quota system that has been reported to date and proposes a framework for discerning the role of the quota system in implementing the nationalization strategy as a tool, a facilitator, an inhibitor, and an assessor for nationalization. We conclude with several recommendations that policy makers and organizations can adopt to improve the efficacy of the quota system.

Introduction

Over the past few years, as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries have acquired financial resources and experienced phenomenal economic development, the growth of the proportion of locals in these countries has gained momentum along with improvements and stability in their lifestyles. In spite of the availability of this growing local human resource, the locals in GCC countries have been experiencing high levels of unemployment (The World Bank Citation2020). In response to these rising levels of unemployment, the GCC governments made drastic policy changes and implemented nationalization or localization strategies that aimed to ensure the availability of employment opportunities for their citizens. Unemployment becomes of national concern to any country, given that it signifies a waste of national resources which otherwise would have contributed to economic growth (Harry Citation2007). Furthermore, continued absence from effective employment can also accrue a pool of troublemakers and increase the crime rate. Hence, nationalization in the GCC region seems basically to be motivated by high unemployment and an increasing birth rate (Rees, Mamman, and Aysha Bin Citation2007; Elbanna Citation2021). Resultantly, GCC governments implemented nationalization strategies in order to provide employment opportunities to locals by focusing on the need to invest in the training of locals, incentivize them to partake in professional and managerial work, and engage women in vocational jobs (General Secretariat for Development Planning Citation2008, Citation2011). Nationalization strategies have been customized to each GCC country in a way that it clearly elicits their goal to hire locals. For instance, nationalization strategy in Qatar has been labelled as Qatarization, while the same strategy was rolled out under the term of Saudization in Saudi Arabia.

To meet the GCC governments’ ambitious targets, several policies were implemented, of which the most popular and widely used was the quota system (Swailes, Al Said, and Fahdi Saleh Citation2012). In general, quotas are identified as government interventions and are implemented as percentages or numbers to enable representation of a select minority group (Mensi-Klarbach and Seierstad Citation2020). Quotas have been implemented globally to provide more opportunities to the under-represented and disadvantaged minority groups (Howard and Prakash Citation2012). Primarily, quotas have been popularly used to enhance representation of females and disabled persons in the society. Gender quotas have been prominently studied in the literature with regard to securing more women representation in politics (Beauregard and Sheppard Citation2021), corporate boards (Bertrand et al. Citation2019; Bhattacharya, Khadka, and Mani Citation2022; Kirsch, Sondergeld, and Wrohlich Citation2022; Mensi-Klarbach and Seierstad Citation2020), and public administration (Hassan and O’Mealia Citation2020). In GCC, the quota system required that a set number of nationals as indicated by the government were hired by the organization on whom the said quota was imposed (Al-Mejren and Erumban Citation2021).

With the primary motivation behind nationalization policies being to increase the number of employed nationals, GCC governments have unanimously made use of quota system mandates in various ways and forms to enforce their nationalization strategies (Fahad and Nair Citation2019). For example, the Saudization strategy enlists quantitative goals, such as hiring an additional 300,000 Saudis and ensuring that by the year 2030, at least 60% of physicians will be Saudis so as to reduce dependence on foreign labour in the health industry (Fahad and Nair Citation2019). Hence, quota system seemed an attractive tool with which the GCC governments could meet their nationalization targets in the short term. However, critics have pointed out the inefficiencies resulting from such regulatory pressures, which, for example, may lead to the employment of underqualified and inexperienced nationals in the workforce (Randeree Citation2012), along with several concerns over its limited long-term success (Elbanna et al. Citation2021).

The excessive dependence among GCC governments on quota system has motivated us to seek answers to the following question: What can we learn from the quota system practices now in place? We further break down this research question into themes to attain a microscopic view of certain aspects of quota system, namely, the uses and challenges of a quota system and how to improve its efficacy. This lets us better understand current practices of quota system, provide a platform for future scholarly studies and inform practitioners of the choices they might make in contributing to the national strategy of nationalization.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. We begin by discussing the term ‘nationalization’ before outlining the methodology and analysis technique used in the study. Next, we discuss the uses and challenges of a quota system, identify ways to improve its efficacy, and finally outline some conclusions.

Understanding nationalization

Nationalization or localization has been identified in different studies as having different goals. Some scholars have treated nationalization strategy merely in numerical terms, where the hiring of locals is promoted over the hiring of expats (Abaker, Al-Titi Omar Ahmad, and Al-Nasr Natheer Citation2019). The quantification of nationalization strategies has led to studies using the term ‘quota system’ synonymously with ‘localization’ (Claude, Martorell, and Tanner Citation2009). At the other end of the spectrum, nationalization strategy has been conceptualized as a strategy that aims to develop local talent to allow for the effective replacement of foreign employees (Ahmed and Khan Citation2014). In both of these conceptualizations, the key seems to be the replacement of expats. While expats may be perceived as a threat to locals, since the groups compete with each other for similar skilled jobs and may make the economy vulnerable, the influx of expats also allows for cheap labour that leads to improved economic competitiveness and growth (Claude, Martorell, and Tanner Citation2009; Alsamara Citation2022). Ramady (Citation2013) points out, as a matter of fact, that most of the jobs taken by expats are perceived by locals to be ‘demeaning’, which further questions the focus on replacing expats as a part of the nationalization strategy. The replacement of expats by locals makes sense so long as these workers are easily substitutable, since the presence of expats can, in fact, lead to more job opportunities for locals. Hence, in economies like the GCC countries that function on the premise of a workforce comprising at least 90% foreigners, the sudden removal or replacement of such employees can be difficult and challenging (Al-Waqfi and Forstenlechner Citation2014).

Thus, the core of a nationalization strategy must be seen as two-fold: 1) providing jobs to locals, and 2) investing and providing support for skills development among locals (Forstenlechner and Mellahi Citation2011). In this regard, Barnett, Malcolm, and Toledo (Citation2015, 298) posit that the current target of nationalization to boost employment needs to be replaced by increasing productivity and efficiency, since it aligns with the country’s national goal of creating a knowledge-based economy; ‘for a country to make progress, people need [to] not just … have a job, but … do a job’. Policy makers and organizations, however, need to take note that, while the first objective of providing jobs to locals may be easier to achieve, it merely provides short-term solutions to a much greater problem: combating local unemployment.

Methodology

Given the relatively small amount of research on the topic of nationalization in the Gulf region, we carried out a broad search of the literature that studied not only quota systems but also nationalization. To this end, we aimed to conduct an integrative literature review by studying the field of quota system based on empirical, conceptual, and theoretical research considering the five characteristics of rigorous literature reviews proposed by Callahan (Citation2014, 272), namely, ‘concise, clear, critical, convincing, and contributive’. In so doing, we carried out a literature search using a variety of keywords considering alternatives and synonyms (Wang Citation2019), including nationalization or localization; workforce nationalization or workforce localization, GCC or Gulf Cooperation Countries; quota system, along with country-specific keywords for nationalization, namely, Qatarization for Qatar, Kuwaitization for Kuwait, Omanization for Oman, Saudization for Saudi Arabia, Emiratization for UAE, and Bahrainization for Bahrain.

Following related reviews on management research in Arab countries in general (Elbanna et al., Citation2020), and workforce nationalization in the GCC countries in particular (Elbanna Citation2021), we searched the literature in five databases, namely, ProQuest, EBSCO, ScienceDirect, JSTOR, and Emerald for the period of 2001–2021 since most research on workforce nationalization in the GCC countries has been published in the last two decades. In expanding our literature search across these various databases, we attempted to avoid presence of any publication bias (Wang Citation2019). Our search was limited to articles written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals. This resulted in the accumulation of 62 research papers. We narrowed this down to 46 relevant studies by reviewing the abstracts and the focus of each study to check their relevance to quota system. These 46 studies were empirical, conceptual, and theoretical in nature. With one exception only (Looney, Citation1991) our literature review before 2001 did not result in any relevant papers.

We made use of a narrative synthesis approach to unravel the various themes that could be attained from reviewing the short-listed 46 research studies. Among the various established tools and techniques that are available for carrying out a narrative synthesis, a thematic analysis technique was chosen given its inductive nature which align with our research paper’s aim to explore the research on prevalent quota system practices in the GCC region, (Popay et al. Citation2006). As such, we then developed a table to list and code all 46 research papers in accordance with their research purpose, research topic and its relation to quota system, country under examination, nature and type of research study, constructs under empirical examination along with sample composition (if any), research questions or hypotheses, research methods, data analysis, and findings (see , Appendix). Following this tabulation, we then categorized the research papers on the basis of two recurrent themes, namely uses and challenges of quota system. We further analysed the studies along with additional quota literature outside the GCC and drew from it to build our findings on how the efficacy of quota system in GCC can be improved. The following sections illustrate our understanding of quota system through these themes that emerged from the 46 studies.

Quota system

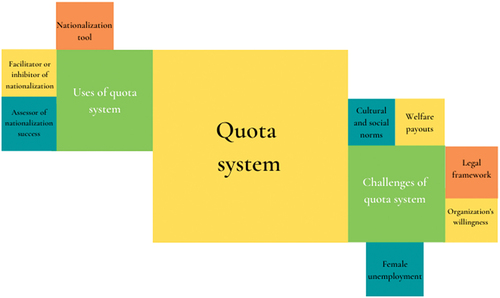

In this section, and as shown in , we aim to paint quota system comprehensively by addressing the various components of our proposed framework, namely, the uses and challenges of quota system, which are discussed in the following subsections.

The uses of quota system

Quotas, by far and large, have been perceived as attractive tools for governments wishing to easily secure opportunities and resources for minorities and as such are subject to institutional drivers (Thompson and Wissink Citation2016; Williams, Ramudu, and Fish Citation2011). Particularly, in the GCC region, quotas have served to facilitate the implementation of nationalization strategies (Jabeen, Mohd Nishat, and Katsioloudes Citation2018). A quota system has made it easier to achieve the first objective of a GCC country’s nationalization strategy; it has been heavily used to enhance local employment through the reservation of certain occupations and trades for locals and the allocation of specific percentages of locals to be employed in certain industries. In this regard, the GCC countries have imposed higher quotas for public sector where the government is able to regulate employment of locals with more ease in comparison to the private sector (Behery Citation2011; Forstenlechner Citation2008). For instance, the government of Qatar required the oil and gas sector predominated by the state-owned organization, Qatar Energy, to achieve a 50% Qatarization rate in contrast to imposing a 20% quota for the private and quasi-private sector (Al-Mejren and Erumban Citation2021). Quotas, however, fail to meet the second objective of nationalization strategy of nurturing and growing local talent to reap long-term benefits and attain higher rates of employment in the foreseeable future. In the following subsections, we take a closer look at the various ways in which quota system has been used in the GCC countries: as a tool to implement nationalization, as a facilitator or an inhibitor of nationalization, and as a measure of successful nationalization.

Tool for implementing nationalization

Quota system was instigated in the GCC countries solely for the purpose of reaching the goals specified in their respective nationalization strategies, thereby making the quota system an effective tool for nationalization. It is interesting to note that most of the industries in the GCC region on which a quota system was imposed were either of national importance or possessed favourable working conditions (such as shorter working hours and less demanding skills requirements making them attractive to locals) (Thompson and Wissink Citation2016). For instance, the banking and airline industries in Oman were chosen to bear the imposition of quotas, given their closeness to national security (Swailes, Al Said, and Fahdi Saleh Citation2012). Organizations in Oman were required to attain 90% nationalization and reserve certain positions – like HR managers, secretarial staff, security officers, and public relations officers – for Omanis (Glaister, Al Amri, and Spicer Citation2019). Similarly, in Qatar, a 100% quota target was imposed for non-specialist jobs in the government sector, followed by a quota of 50% locals in the oil and gas sector and 20% of the workforce in the private sector (Williams, Ramudu, and Fish Citation2011; Gupta, Cullinan, and Filocca Citation2021). A similar approach was followed in Saudi Arabia, which required a general quota of 30% locals working in private organizations and specific percentages for certain industries (Williams, Ramudu, and Fish Citation2011; Ashok, Al Sherbini, and Al Mulla Citation2021). United Arab Emirates (UAE), following similar targets, provided around 20,000 jobs for nationals in 2019 in strategic industries that included banking, civil aviation, and others (Emirates News Agency Citation2019).

Across the GCC countries, the quota system has been taken up as a straitjacket approach using the concept of ‘one size fits all’. The region saw imposition of general quotas such as allocating 25% of available jobs to locals in Saudi Arabia and requiring a 5% annual increase in employed nationals in Bahrain’s private sector (Al-Mejren and Erumban Citation2021). However, recent changes have been made whereby different sectors in the GCC region have been given different quota targets to facilitate a smoother inflow of locals. For instance, Saudi Arabia has implemented a nation-wide quota system under the label of ‘Nitaqat’, which divides organizations into categories based on the number of locals required to meet the quotas imposed on them (Williams, Ramudu, and Fish Citation2011). Nitaqat is believed to be a more realistic version of the previous generic quotas, where quotas are estimated according to the nature of an industry and the size of a firm in order to satisfy the rising concerns from the private sector about the availability of qualified locals (Williams, Ramudu, and Fish Citation2011; Peck Citation2017). Thus, quotas have been used collectively across the GCC region to easily provide jobs to locals given its transparency in delivering numbers. However, we illustrate below the extent to which quotas actually did facilitate or limit the overall goals in nationalization.

Facilitator or inhibitor of nationalization

The overarching goal of a nationalization strategy relates to improving local employment; this has meant that not enough thought has been given to enhancing the productivity of local employees. As a result, quota system, the standard tool in the GCC to implement nationalization, also suffers from similar drawbacks where the resultant metric merely assesses the number of employed nationals and not the development of a competitive local labour force (Toledo Citation2013; Elbanna Citation2021). Additionally, quota system that required a partnership condition seems to not work towards a government’s nationalization strategy because the government’s generous payments to its citizens in return for their loyalty and for not inciting political reforms has developed a patron state with a patrimonial structure (Thompson and Wissink Citation2016).

At the outset, though quota system was developed to benefit nationals, it has managed to do quite the opposite. From an organizational perspective, the ‘ceremonial adoption’ of quotas means that organizations are meeting quota targets merely to ascertain their legitimacy and maintain their business (Sidani and Al Ariss Citation2014). Further, quotas have now become a numbers game in which private sector organizations merely hire locals to comply with the rules (Swailes, Al Said, and Fahdi Saleh Citation2012). Such compliance is also driven by the incentives offered by GCC governments to the private sector. Governments incentivize organizations by making large-scale bids conditional on nationalization or requiring organizations to pay the difference in wages between the nationals employed in the public sector and those in the private sector (Forstenlechner and Rutledge Citation2010). Other financial incentives include lower funds or financial guarantees for companies that meet their quota requirements and lower fees for issuing work permits (Aljanahi Citation2017). Hence, in their efforts to secure government contracts and enjoy these benefits, organizations have responded by hiring nationals for more visible positions (Forstenlechner and Mellahi Citation2011; Elbanna Citation2021).

At the same time, in order to comply with government’s quota mandates, organizations also try to accommodate the hiring of more locals by lowering the job requirements (Marchon and Toledo Citation2014). Such window-dressing has led to the development and persistence of beliefs regarding inappropriate work attitudes and inefficient work abilities of locals in comparison to expats (Alserhan Citation2013; Said, Abdelzaher, and Ramadan Citation2020). Conspicuously, quotas are perceived by profit-making private organizations as an expensive investment that leads them to resort to other options such as outsourcing services or reducing capital so as to qualify for lower quota categories (Barnett, Malcolm, and Toledo Citation2015). Further, the rapid implementation of quotas such as that of Nitaqat in Saudi Arabia, where sanctions were imposed on organizations within 8 months, did not allow organizations enough time to adjust their staffing levels, thereby producing a higher negative impact than longer phase-ins would have caused (Peck Citation2017).

As wisely noted by Moideenkutty, Murthy, and Al-Lamky (Citation2016, 8), it indeed seems to be the case that ‘[national]ization policies that aim to merely meet the quotas may not pay off’. While some countries like UAE ensured that its nationalization strategy included facets such as training and development, the associated high costs of engaging in such activities have motivated organizations to resort to mechanical compliance with quota system as the better option with reduced costs (Rees, Mamman, and Aysha Bin Citation2007). In this situation, these private organizations were required by the UAE government to pay a levy that would contribute to the training and hiring of locals. Private organizations under such government coercion have also been found to engage in malpractices such as adding locals to the employee payroll merely to fulfil quota requirements and to escape the cost of hiring natives as full-time employees (Parcero and Christopher Ryan Citation2017).

Assessor of nationalization success

The Nitaqat quota system in Saudi Arabia assesses the numbers of male and female locals employed, the number of locals employed in managerial or higher roles, the duration of each local employee’s service, and the proportion of locals employed as senior well-paid managers (Abaker, Al-Titi Omar Ahmad, and Al-Nasr Natheer Citation2019). This quantitative enquiry, however, should not be used as a sole performance indicator to assess the success of nationalization policies. It needs to be combined with other quantitative metrics such as 1) the promotion prospects of nationals, and 2) the training and support given to nationals (Forstenlechner et al. Citation2012). GCC countries have gone through a learning curve to realize that, in addition to providing jobs, their nationalization strategies need to be supplemented with the objective of enhancing the quality of education given to locals. While some countries like UAE have responded to these changes in the nationalization strategy and moved beyond imposing quotas to incorporate skill development and career enhancement, the assessment of nationalization success is still mostly based on measuring the number of nationals being employed under the quotas (Al-Mejren and Erumban Citation2021, 89). Hence, given the multifaceted goals of nationalization, using a quota system as the only measure of success may not be sufficient; it leads to a misalignment between the nationalization goals and the measures of success for this system. For example, a study by Forstenlechner (Citation2008) produced anecdotal evidence that nationalization was attained through ensuring proper training, implementing reward structures, exposing locals to other cultures, and by having organizations determined and committed to investing in the development of local talent. Thus, using a quota system to measure the effectiveness of nationalization strategies in use may not be the most apt measure because it diverts the focus from quality, effectiveness, efficiency, work satisfaction, and professional skills.

Challenges of the quota system

Despite the prevalence of quota system for over a decade, it has still not managed to sufficiently increase the number of nationals employed in the private sector (Ingo, Lettice, and Özbilgin Citation2012; Said, Abdelzaher, and Ramadan Citation2020). This has led us to question the barriers and challenges associated with the use of quota system in the GCC countries, as discussed in the following sub-sections. Scholars have offered various reasons for the lack of efficacy of quotas, namely, their rejection by organizations due to high economic costs, failure to adhere to them when the local workforce does not meet the job requirements, and the ability of organizations to evade them (Al-Dosary, Masiur Rahman, and Adedoyin Aina Citation2006; Al-Waqfi and Forstenlechner Citation2014).

Cultural and social norms

The workforce culture and policies in place have made it difficult for organizations to meet the ambitious quota targets set by the GCC governments. In addition, the local culture and attitudes of young people clash with the quota system enforced across GCC countries. Locals prefer jobs that are culturally suitable and closer to or in the public sector with a lower preference for jobs requiring manual, specialized, technical, or administrative skills (Peck Citation2017; Mellahi Citation2007). Similarly, the quotas placed on specific positions or industries have instilled a sense of social acceptability or preference among locals towards these particular positions (Forstenlechner and Rutledge Citation2010). With this being the case, locals opt for luxury employment, where they take negligible part in productive employment and as a result, their development of talent and skills is stunted (Al-Mejren and Erumban Citation2021). Locals, particularly in the UAE, have been posited to possess a ‘mudir’ or manager mentality, where the only acceptable jobs are those that provide respect, status, and authority (Thompson and Wissink Citation2016). There is also a unique societal context in the GCC pertaining to the preference for certain jobs and industries for women as well: women prefer the public sector over the private sector due to its higher benefits like generous retirement packages, shorter working hours and the perception of communal values (Marmenout and Lirio Citation2014).

The high wages and increased benefits demanded by some locals have developed a widespread belief among private organizations that hiring nationals is more expensive than hiring foreigners (Harry Citation2007). Further, locals are also regarded as being less disciplined and lacking the proper work attitude such as being punctual to work and working hard (Mellahi Citation2007; Elbanna Citation2021). These stereotypes have led to the belief among potential employers that hiring locals will adversely affect organizational performance (Ingo, Lettice, and Özbilgin Citation2012). Additionally, since private organizations treat quotas as a burden, their strategies in response to this perception are to make use of ghost workers or hire unqualified and low skilled nationals (Al-Waqfi and Forstenlechner Citation2010). Moreover, in Saudi Arabia, employers were found to perceive that the graduates from specific schools lacked real-world skills; as a result, they shied away from hiring local graduates (Al-Dosary, Masiur Rahman, and Adedoyin Aina Citation2006). Similarly, nationals hired through the quota system were labelled ‘quota guys’, repressing local employees’ inclination to work hard (Ingo, Lettice, and Özbilgin Citation2012). Similar labels like ‘quota woman’ were also used in Germany to assert the lower skills or qualifications of the hired woman in compliance to the government enforced gender quota (Schmitt Citation2015). As such, females were stigmatized for being the expected beneficiaries of such quotas, where in the absence of these quotas females were perceived to not hold the necessary skills needed for the job (Beauregard and Sheppard Citation2021). In GCC, such activities in organizations have added to the negative stereotypes of under-skilled locals representing an inherent bias against locals, while the cultivation of preferences among locals for particular types of job have put the successful implementation of quota system beyond attainment.

Welfare payouts

Generous welfare benefits or ‘rents’ offered by governments to locals as a part of their ‘cradle to grave welfare system’ have created a vicious cycle where nationals have developed negative attitudes to work and, as a result, prefer to stay out of a large area of the job market (Williams, Ramudu, and Fish Citation2011; Thompson and Wissink Citation2016). In short, these generous welfare programmes have reduced the incentives for locals to work hard. In Qatar, one of the most extreme welfare states, locals would rather be unemployed than pursue employment in the private sector given its accompanying low status and low pay (Williams, Ramudu, and Fish Citation2011; Parcero and Christopher Ryan Citation2017). In accordance with this view, nearly 85.7% of unemployed Qataris and 58% of unemployed Kuwaitis were unwilling to work in the private sector (Planning and Statistics Authority Citation2020b; Central Statistical Bureau Citation2016). Resultantly, locals in the GCC region were primarily employed in the public sectors such that in UAE, nearly 40% of employees were Emirati, whereas this statistic was much higher at 79% in Qatar and at 86.6% in Kuwait (Federal Competitiveness and Statistics Centre Citation2019; Planning and Statistics Authority Citation2020a).

On the contrary, a significantly higher number of nationals were found to be employed in the private sector in neighbouring GCC countries of Bahrain and Oman. While this finding was uniform to both Bahraini males and females such that the overall number of male and female Bahrainis working in the private sector in 2020 (10,4775 Bahrainis) was twice as that of the public sector (47,993 Bahrainis), however, the Omani labour market had a different story to tell (LMRA Citation2021b). The Omani labour market also showed promising results with respect to twice the number of Omani males employed in the private sector in 2020 (18,7391 Omanis) in comparison to the public sector (93,390 Omanis). However, the number of Omani females working in the private sector (67,363 Omanis) still fell short of those employed in the public sector (82,461 Omanis) (NCSI Citation2022).

Thus, as citizens deem such government payouts, in the form of guaranteed public jobs funded by oil revenues, as rightful and find a basis for them in their tribal backgrounds, governments continue to find it difficult to improve local employment in the private sector (Biygautane, Gerber, and Hodge Citation2017). The GCC governments have also tried increasing the national wages paid out of GDP and have maximized budget allocations to the public sector in order to increase the size of their ministries and offer more public sector employment opportunities to locals (Harry Citation2007). Not surprisingly, the public sector is now saturated with locals and no longer able to provide benefits to all nationals. Hence, overt reliance on quota system harms the economies since governments hire locals for non-existent jobs and employment becomes a social welfare system.

Legal framework

The current inclusion of quota system has been discussed mostly in terms of the legal framework that has led to quota system being perceived as solely comprising quantitative targets. Additionally, governments have added to this perception by providing preferential considerations and incentives to organizations that meet their individual quota targets (Moideenkutty, Murthy, and Al-Lamky Citation2016). These regulatory pressures resulted in mixed outcomes where few organizations took steps to ensure that local talent was hired, while others resorted to hiring ‘ghost workers’ to meet the competitive quota targets, thereby providing local employment reflected only in statistical terms (Moideenkutty, Murthy, and Al-Lamky Citation2016; Forstenlechner Citation2008). Hence, organizations paid lip service to the rules and employed the minimum number of required locals, indicating that such adherence to the quota system has come due to the fear of penalties and has no basis in morality.

Organizations that managed to reach the ambitious quota targets, however, did so at the cost of their profits or survival (Elbanna Citation2021). Such negative outcomes of organizations exiting the industry due to the imposition of quota system have also forced governments to modify these quotas and not impose them rigorously. The UAE government, for example, imposed low fines, which organizations preferred to the costs of hiring and training locals (Forstenlechner and Rutledge Citation2010). Similar lax behaviour was also seen in earlier regulatory phases in Saudi Arabia regarding the percentage of Saudis that had to be employed in the private sector although this behaviour has recently changed (Dosary and Adel Citation2004). Further, scepticism over negative consequences might follow non-compliance and may further reduce adherence to the imposed quotas (Ingo, Lettice, and Özbilgin Citation2012). Thus, it comes as no surprise that quota system did not yield tangible results since it was not enforced appropriately.

Additionally, some governments have also imposed quotas on work permits for foreign labour to enable organizations to meet the quota targets for hiring locals (Dosary and Adel Citation2004; Pech Citation2009). For instance, Saudi Arabia imposed a general cap of 20% on hiring foreign labour, with additional specific quotas of 10% on the work permits available to each country that exports labour to Saudi Arabia (Bosbait and Wilson Citation2005). However, such direct interventions on the part of the government restricts the labour market’s attempts to meet its own needs and destroys its equilibrium. This was witnessed in Saudi Arabia, where such governmental interventions led to the rise of visa trafficking: organizations used illegal means by Saudi sponsors to acquire extra work visas (Mellahi Citation2007). In addition to placing limits on the numbers of hired foreigners and setting minimum quotas on the hiring of locals, the GCC governments have also raised the cost of hiring expats (Alzahmi and Imroz Citation2012). As a result, GCC governments may have to deal with great challenges such as the imminent brain drain of foreign workers in order to prevent the consequential negative impact on productivity.

The legal framework that has mandated quotas to increase the hiring of nationals in the private sector has also created a dual HRM model that applies one policy for nationals and another for foreigners (Mellahi Citation2007; Thompson and Wissink Citation2016). Thus, the prevalent labour market in the GCC region has been stratified into two non-competing segments of locals and expats. High levels of difference exist in the treatment of locals and foreigners due to government policies resulting in private organizations having more control over foreign employees than local ones. Even when they possess a low skill set, locals are accustomed to expecting a well-paid job because governments multiply jobs in the public sector and hire candidates irrespective of their academic qualifications (Biygautane, Gerber, and Hodge Citation2017; Claude, Martorell, and Tanner Citation2009). Consequently, local employees demand high wages for doing what expats do more cheaply, particularly since locals who want to work in the competitive private sector are required to acquire higher skills.

Unsurprisingly, countries like Kuwait find stark contrast in the wage distribution amongst nationals and expats, where nearly 56.3% and 96.2% of expats in public and private sectors earned less than KWD 600 per month (US$ 1,955). On the other hand, 20.6% Kuwaitis earned nearly twice the amount of wages with an average of KWD 1,100 to 1,199 per month (US$ 3,585 to US$ 3,908) in the government sector, while 16.6% Kuwaitis earned more than KWD 2,000 (US$ 6,519) in the private sector (Central Statistical Bureau Citation2016). Similar differences are also observed in Bahrain, where the wage gap between nationals and expatriates was around BHD 339 (US$ 901), while the wage difference for Bahrainis in the public and private sector was around BHD 105 (US$ 279) (LMRA Citation2021a). Consequently, requiring such a further increase in educational qualifications widens the wage gap between nationals and locals and reduces the motivation of nationals to consider the private sector (Forstenlechner and Rutledge Citation2010; Elbanna Citation2021). Hence, government-imposed employment quotas have led to the development of a price-differential wage since private employers are forced to hire less well-qualified locals at higher wages; thereby causing a ‘catch-22’ situation such that nationalization has damaged its own progress by creating the challenge of a local-migrant wage differential (Alfarhan and Al-Busaidi Citation2018).

Organizations’ unwillingness

Imposing a quota system on foreign companies has made them nervous to the extent that they have embraced various methods of eluding the need to hire locals (Ingo, Lettice, and Özbilgin Citation2012). Interestingly, private organizations have used wasta (personal connections) to overcome government-imposed quotas (Harry Citation2007). When the government reserved certain positions for locals, organizations reclassified existing job titles so as to retain the current expats and not bear the extra cost of hiring and training locals (Forstenlechner et al. Citation2012). Such instances of quota avoidance by organizations are not new and have already been experienced in Norway, where organizations have even changed their ownership structure and legal status to avoid falling under the quota policy (Bertrand et al. Citation2019; Seierstad et al. Citation2021). In such contexts, organizations perceive human resources as a cost rather than a valuable asset that can be invested in. This resistance may be attributed to the way that organizations have perceived the quota system mandates: as a form of indirect taxation (Forstenlechner et al. Citation2012).

Quotas, when forced on organizations, can drive them out of business and indeed reduce employment opportunities for locals. Additionally, quota system is not helpful in boosting the employment of locals in the private sector due to the high wages that locals insist on and the mismatch in their skills. This leads to a huge gap in a local employee’s psychological contract; organizations mindful of their budget restrictions are unwilling to hire locals, pay them high wages and train them (Al-Waqfi and Forstenlechner Citation2014; Ahmed and Khan Citation2014). When a private firm does hire locals, it experiences high turnover because locals leave due to the low remuneration packages they are offered compared to their prospects in the public sector (Swailes, Al Said, and Fahdi Saleh Citation2012; Ingo, Lettice, and Özbilgin Citation2012). The UAE banking sector, for example, faced such retention problems, finding that only 40% of the locals they hired remained in their jobs (Forstenlechner Citation2008). Hence, the high turnover rate of locals has also played a part in making private organizations reluctant to hire nationals who are prone to leaving as soon as vacancies arise in the public sector.

Further, as organizations are faced with quotas, their production costs increase in the presence of less elastic demand and an inability to replace inputs (both expats and locals) (Marchon and Toledo Citation2014). Evidence of this was found in jewellery stores, cab services, and vegetable markets that had quotas reserved for Saudis (Bosbait and Wilson Citation2005). In addition, as argued by Biygautane, Gerber, and Hodge (Citation2017), unwillingness to hire locals is noticed at times from policy makers who may have local business interests and at the end of the day support the hiring of foreign labour in preference to expensive locals.

Women unemployment

Quotas have been placed in order to compel organizations to offer more job opportunities to local women. Saudi Arabia’s Nitaqat system and the quota system in Bahrain consider the hiring of one local woman equivalent to hiring two locals (Tlaiss and Al Waqfi Citation2020; Rutledge et al. Citation2011). While such government impositions have increased the employment of local women, it has also inadvertently led to employers engaging in window dressing activities to meet the quota requirements (Rutledge et al. Citation2011). Moreover, in spite of the availability of educated women, the quota system was not able to deliver higher employment rates for women owing to existing social and cultural norms. Under these norms, women do not prefer working in a mixed environment or with inflexible work hours (Claude, Martorell, and Tanner Citation2009; Elbanna Citation2021).

Further, the patriarchal culture in Arab countries, in general, and the GCC region, in particular, has been a hurdle in fostering women’s employment (Tlaiss and Al Waqfi Citation2020). The participation of local women in the labour market is dictated by ‘aib’ (shame), which is prevalent as a cultural norm and requires the labour market to create more jobs that are culturally deemed fit for local women (Harry Citation2007). In addition, it has been discovered that women pursue higher education and tend to stay longer in schools because of these barriers and the restricted availability of fields of employment (Al-Dosary, Masiur Rahman, and Adedoyin Aina Citation2006). These varied reasons underlying local women’s unwillingness to take up jobs available through the quota system makes it difficult to implement this system as a stand-alone strategy that would lead to nationalization in practice.

Improving the efficacy of the quota system in the GCC region

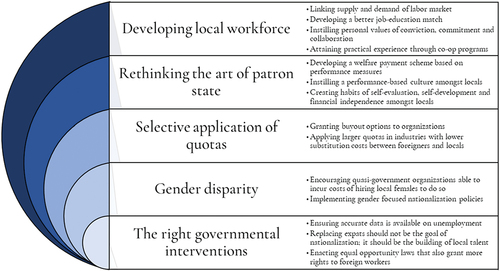

The quota system in this region does not bridge the gap between what organizations desire in local employees and what skills locals have to offer. Hence, the GCC countries need to allow for the inclusion of supplementary strategies that focus on the legal and institutional framework alongside the quota system in order to facilitate local employment. In this section, we look at some strategies that could be adopted to improve the effectiveness of the quota system as depicted in below.

Developing local workforce

The sociocultural and national aspects of using and developing the local workforce need to be outlined. Skills development, effective regulatory and institutional tools, social and economic reforms, and women employment need to accompany the process (Al-Waqfi and Forstenlechner Citation2014; Al-Dosary, Masiur Rahman, and Adedoyin Aina Citation2006; Moideenkutty, Murthy, and Al-Lamky Citation2016). Further, these initiatives need to be provided with time-specific incentives consonant with the market forces to ensure their effective implementation.

The effectiveness of workforce development needs to be recognized through ensuring a proper linkage of labour market supply with demand and building employee resilience (Alzahmi and Imroz Citation2012). Hence, there is a need for market-driven and fine-tuned education, where the education provided in schools is in alignment with the skills needed at work. This can be attained by sharing data across ministries and consulting with the private sector to plan educational reforms. In ensuring that locals have a better job/education match, the GCC countries can improve local workers’ productivity by tying their wages to performance and not welfare. So far, higher education has been ‘a by-product of spending’ rather than the pursuit of personal interests accompanied by a well-thought-out plan. Additionally, the education system in the GCC region has focused on creating a national identity instead of a productive workforce (Harry Citation2007). This has led to an unbalanced emphasis on certain subjects like education and business, while other fields such as technical education remained neglected (Rutledge et al. Citation2011; Elbanna Citation2021).

Moreover, in order to ensure that nationalization strategies are effectively implemented, locals need to receive proper training and career planning to instil a sense of job security, particularly in the private sector. It is important to note that training should be given in terms of individual values and not merely work skills; locals need to have values that are in alignment with those of their employers to ensue ‘conviction, commitment and collaboration’ (Pech Citation2009). Further, it should be possible to require nationals to accrue significant experience in private organizations and demonstrate quality skills before they seek employment in the public sector. This strategy would allow locals to attain the first-hand experience of probing into the workings of the private sector and overcome their doubts about its high competitiveness and unattractiveness. Once they have developed such local talent, the GCC governments can impose restrictions on organizations that hire expats alone when qualified nationals are also available (Al-Waqfi and Forstenlechner Citation2014).

Rethinking the art of patron state

Quota on its own does not create new jobs; rather the programme needs to focus on the active labour market, since the creation and availability of jobs for locals is affected by paying them higher wages, their lower productivity, and availability of a skilled local workforce (Barnett, Malcolm, and Toledo Citation2015; Al-Waqfi and Forstenlechner Citation2010). Hence, the GCC governments need to find alternative ways of distributing their hydrocarbon wealth to enhance local talent in non-distortive ways. They should provide more benefits to the sectors that bring in more production and growth and not restrict themselves to providing public jobs through a quota system that reduces competition. In order to restrict the incidence of today’s negative outcomes, the GCC governments need to create a welfare payment scheme that is established around assessments of locals’ performance (Toledo Citation2013). In so doing, the private sector may also begin to clearly see the benefits of hiring locals and inculcate a more agreeable hiring behaviour of locals by the private sector. Hence, nationalization needs to be market-based, as opposed to being a national decree.

Since the effective implementation of HRM policies can occur only by combining legal and normative approaches, the GCC governments must try to reduce the negative perceptions amongst nationals in the private sector and refine the existing local culture that currently focuses more on prestige than performance (Parcero and Christopher Ryan Citation2017; Mellahi Citation2007). Remedying these social and cultural factors will indeed take time and, hence, needs to be supplemented with the above suggestions for developing co-operative programmes that are socially acceptable. Using economic diversification as a tool, governments can diversify the list of jobs that are socially acceptable to nationals and expand their employers of choice to expand beyond the public sector (Forstenlechner and Rutledge Citation2010).

Currently, the governments in GCC countries have a social contract with their citizens whereby the latter pay political obedience in return for public sector jobs with high job security, low taxes, and free social services (Swailes, Al Said, and Fahdi Saleh Citation2012). However, this relationship needs to be converted to one of social exchange, whereby private sector employers can employ and train locals, who in return will deliver work above and beyond the stipulated level (Moideenkutty, Murthy, and Al-Lamky Citation2016). This could also be facilitated by allowing locals to develop habits of self-evaluation for self-development purposes as a part of training programmes. In addition, the concept of financial independence needs to be ingrained in the mindset of locals to strengthen their motivation for seeking employment.

Selective application of quotas

In considering the high costs associated with the quota system, one needs to weigh the suitability of quotas to a specific industry. Organizations, instead of hiring locals, could be given a buyout option to pay taxes which could then be used by the government for enhancing local workers’ skills (Barnett, Malcolm, and Toledo Citation2015). According to Toledo (Citation2013), quotas are easier to implement in imperfectly competitive markets since organizations in such markets can, in the short run, cover up the costs of implementing a quota system by monopoly rents. Quotas will also deliver more positive outcomes in sectors where it is easy to substitute a local workforce for a foreign one, which would reduce the costs of production. While a quota system states what needs to be achieved as the final outcome, it fails to provide the participating organizations with information on how to attain it. This is where policy makers and scholars can contribute by providing helpful information on what actual practices organizations can engage in to meet the government’s quotas without hampering the organization’s efficiency and profits.

Gender disparity

Hiring local women sometimes comes with additional fixed costs due to the cultural forces at play. These may include having different entrances and work spaces for women only (Peck Citation2017). The added costs of hiring local women can be taken up by quasi-governmental organizations in GCC who have sufficient resources to cater to local women’s employment needs (Rutledge et al. Citation2011). Local women in GCC are considered a ‘valuable human resource’ with untapped talent possessing high levels of education, yet seemingly have a lower representation in the workforce due to cultural and structural barriers (Rutledge et al. Citation2011; Elbanna et al. Citation2021). Interestingly, organizations in GCC countries have no specific laws pertaining to gender discrimination (Tlaiss and Al Waqfi Citation2020). Moreover, the core of nationalization policies are also not gender focused although there is a growing pool of local women university graduates whose high educational attainment is not being transferred to the workplace (Rutledge et al. Citation2011; Marmenout and Lirio Citation2014). This may motivate the otherwise hesitant private organizations to focus on hiring local women in order to meet multiple government mandates of hiring locals and hiring local women. Thus, there is a need for policy implications that improve the representation of local women and allow their seamless integration in the professional realm particularly in leadership positions.

The right governmental interventions

Overall, in the absence of skilled locals, governments have restricted their nationalization policies to specific areas of national interest such as the military or public sector (Elbanna et al. Citation2021). However, this can be altered because nationalization does not merely focus on increasing the number of employed nationals, but also includes enhancing the skills of nationals and developing local talent, something that is not achieved by the current quota system. Governments need to ensure that reliable and accurate data on local unemployment is collected to assist in effective problem solving in view of different types of unemployment – voluntary or involuntary – as each may need specific solutions rather than implementation of a standard quota system. Furthermore, in promoting the replacement of expats by locals as one of the goals of nationalization, the GCC governments have made it difficult for private organizations in competitive markets to perceive nationalization as a profitable investment. As employer’s resistance to nationalization strategies grows concerningly, it needs to be tackled as soon as possible. Thus, this particular goal of nationalization strategies needs to be revised to focus on building local talent rather than replacing expats.

GCC governments need to consider including an overall goal of removing employment discrimination of any form that can assist them in combating current issues of not just local unemployment but also control for the unintended spillover negative consequences of quota system such as negative stereotypes towards locals and window-dressing employment practices of organizations, to name a few. Such governmental practices alongside implementation of a quota system were observed to deliver promising results globally. Sweden, in comparison to fellow OECD countries that imposed employment quotas for its disabled population, was able to garner higher employment for the disabled minorities due to the establishment of societal principles of equal opportunity for all along with provision of various incentives for organizations hiring disabled persons (Yoshihiko Citation2019). Similarly, social norms were found to be a major contributor of promoting employment of disabled minorities in Japan and supported the organizations in satisfying the government-imposed quota targets without having to pay any levies for incompliance (Mori and Sakamoto Citation2018). While some governments like Austria and Germany exclusively made use of quota system to develop more employment opportunities for disabled persons, however, other governments such as South Korea and United States also passed anti-discriminatory laws with the essential goal of eliminating employment discrimination (Nazarov, Kang, and von Schrader Citation2015). In short, quota system can fulfill its intended purpose when coupled with a code of good practice (Seierstad et al. Citation2021). Thus, governments in GCC can consider enactment of employment laws that favour the population, at large and also work in securing employment for the minority population of locals. In this regard, GCC governments need to grant more mobility to foreign workers and thus, widen the scope for creating more job opportunities for both expats and locals that provide a long-term solution to the problem of unemployment (Toledo Citation2013).

Conclusion

Quotas are a radical approach driven by outcomes such that it has developed a climate of excessive focus on measuring the success of the nationalization strategy using quantitative measures, while giving little attention to qualitative measures such as attitudes to nationalization (Rees, Mamman, and Aysha Bin Citation2007; Mensi-Klarbach and Seierstad Citation2020). In this research study, we attempted to portray a comprehensive understanding of the quota practices in place in the GCC region through gathering insights on the underlying uses and challenges of quota system and informing researchers and practitioners alike on various ways in which quota system can be made more effective. It is interesting to note that in its strive to provide more opportunities to the under-represented communities, quotas may have also inadvertently resulted in discriminating against the qualified candidates who are not a part of the minority group (Schmitt Citation2015). Thus, while quotas can serve as an effective tool to provide more opportunities to the minority group; however, in the absence of eligible minority candidates, quotas may have instilled negative stereotypes (Bertrand et al. Citation2019). Resultantly, forcible hiring of ineligible or subpar candidates would lead to the goal of nationalization not being accomplished through quota system. As a result, we need to realize that nationalization is more than meeting quotas and look beyond numbers, disregarding the fact that organizations in GCC, both private and public, are nowadays assessed and incentivized according to their ability to meet these quotas. A quota system is merely one of many ways in which GCC countries can improve the employment of locals; other ways include the alignment of education with market needs, economic diversification from hydrocarbons, and developing a knowledge-based economy (Parcero and Christopher Ryan Citation2017). Even on a global scale, quota system on its own has not been regarded as an effective tool to dissolve the disparities amongst minority representation in a country’s workforce composition (Maida and Weber Citation2022).

Theoretical implications

In examining the literature on quota system in the GCC region, we contribute to the extant research on quotas and provide a comprehensive view of the under-examined region. This study also contributes to workforce diversity literature, where governments have made use of quotas to inculcate a more diverse workforce that provides equal opportunities to the minority groups of women, disabled persons, or in the case of this research study, nationals (Harrison and Klein Citation2007). Through making use of a narrative synthesis approach, we were able to shed light on certain themes of quota system, namely, its uses and challenges and propose a framework that directs attention to various parties such as the government, organizations, policy makers, and individuals. However, given the subjective and storytelling nature of our analysis approach, the analysis process is not highly rigorous (Popay et al. Citation2006). Accordingly, future scholars can advance our research by carrying out more statistically supported reviews such as a meta-analysis. Scholars can also empirically examine the potential of measuring nationalization success using a more representative measure that goes beyond the quantitative nature of the quota system. Our findings also portray the inter-relation of different factors in development of human resources such as education, culture, attitudes of locals, organization’s willingness, and more. Through empirically examining the impact of these various factors on the implementation of quota system, future research can further inform HRD research in the GCC region. In focusing on human capacity development in the Gulf region, this paper provides a focused albeit comprehensive overview on governmental practices towards harnessing local human resources and converting them into real economic development. Additionally, in carrying out an integrative literature review on quota system, this study adds to the developing stream of unique reviews in human resource development literature (Callahan Citation2014).

Practical implications

Our study was able to deliver various practical takeaway points for human resource development strategies for the Gulf region. Amongst other strategies, we find that in addition to ensuring that locals’ skills match the market needs through developing an improved education system, an attitudinal change amongst locals is also urgently needed and so is organizations’ willingness to hire locals. The governments in question can play a lead role in regulating the economy and exercising their country’s cultural and social norms to its advantage through mandating the training of locals, linking the structure of welfare payments to performance assessments, promoting a performance-based work culture, reducing the gaps between foreigners and nationals in matters of wages and employees’ rights, and normalizing the role of working women in a range of disciplines. These suggestions for local Gulf human resource development require much time and effort from many parties: policy makers, organizations, media, and individuals. However, we expect that with their combined efforts, the GCC countries can develop knowledge-based economies that nurture local talent. It is worth noting that although GCC countries are demographically and culturally similar, there is ‘no one way to localize’ and hence, future researchers and policy makers need to understand the national-level circumstances that shape each country and inhibit successful implementation of quota system policies. Researchers need also to explore how the new flexible working practices associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, such as flexible hours and remote work, influence women’s quota system.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abaker, M.-O.-S.-M., K. Al-Titi Omar Ahmad, and S. Al-Nasr Natheer. 2019. “Organizational Policies and Diversity Management in Saudi Arabia.” Employee Relations: The International Journal 41 (3): 454–474. doi:10.1108/ER-05-2017-0104.

- Ahmed, A.-A., and S. A. Khan. 2014. “Workforce Localization in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Issues and Challenges.” Human Resource Development International 17 (2): 243–253. doi:10.1080/13678868.2013.836783.

- Al-Dosary, A. S., and S. Masiur Rahman. 2005. “Saudization (Localization) – a Critical Review.” Human Resource Development International 8 (4): 495–502. doi:10.1080/13678860500289534.

- Al-Dosary, A. S., S. Masiur Rahman, and Y. Adedoyin Aina. 2006. “A Communicative Planning Approach to Combat Graduate Unemployment in Saudi Arabia.” Human Resource Development International 9 (3): 397–414. doi:10.1080/13678860600893581.

- Al-Mejren, A. A., and A. A. Erumban. 2021. Gcc Job Nationalization Policies: A Trade-Off Between Productivity and Employment. edited by C. Keating: The Conference Board.

- Al-Waqfi, M., and I. Forstenlechner. 2010. “Stereotyping of Citizens in an Expatriate-Dominated Labour Market: Implications for Workforce Localisation Policy.” Employee Relations 32 (4): 364–381. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01425451011051596.

- Al-Waqfi, M. A., and I. Forstenlechner. 2014. “Barriers to Emiratization: The Role of Policy Design and Institutional Environment in Determining the Effectiveness of Emiratization.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25 (2): 167. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.826913.

- Alfarhan, U. F., and S. Al-Busaidi. 2018. “A “Catch-22”: Self-Inflicted Failure of Gcc Nationalization Policies.” International Journal of Manpower 39 (4): 637–655. doi:10.1108/IJM-07-2017-0174.

- Aljanahi, M. H. 2017. “Challenges to the Emiratisation Process: Content Analysis.” Human Resource Development International 20 (1): 9–17. doi:10.1080/13678868.2016.1218661.

- Alsamara, M. 2022. “Do Labor Remittance Outflows Retard Economic Growth in Qatar? Evidence from Nonlinear Cointegration.” The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance 83: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.qref.2021.11.002.

- Alserhan, B. A. 2013. “Branding Employment Related Public Policies: Evidence from a Non-Western Context.” Employee Relations 35 (4): 423–440. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2012-0065.

- Alzahmi, R. A., and S. M. Imroz. 2012. “A Look at Factors Influencing the Uae Workforce Education and Development System.” Journal of Global Intelligence & Policy 5 (8): 69–90.

- Ashok, R., R. Al Sherbini, and Y. Al Mulla. 2021. “Jobs in the Gulf: Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Oman Seek Workforce of Nationals.” Gulf News. https://gulfnews.com/special-reports/jobs-in-the-gulf-saudi-arabia-kuwait-oman-seek-workforce-of-nationals-1.76925766.

- Barnett, A. H., M. Malcolm, and H. Toledo. 2015. “Shooting the Goose That Lays the Golden Egg: The Case of UAE Employment Policy.” Journal of Economic Studies 42 (2): 285–302. doi:10.1108/JES-10-2013-0159.

- Beauregard, K., and J. Sheppard. 2021. “Antiwomen but Proquota: Disaggregating Sexism and Support for Gender Quota Policies.” Political Psychology 42 (2): 219–237. doi:10.1111/pops.12696.

- Behery, M. 2011. “High Involvement Work Practices That Really Count: Perspectives from the UAE.” International Journal of Commerce and Management 21 (1): 21–45. doi:10.1108/10569211111111685.

- Bertrand, M., S. E. Black, S. Jensen, and A. Lleras-Muney. 2019. “Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Board Quotas on Female Labour Market Outcomes in Norway.” The Review of Economic Studies 86 (1): 191–239. doi:10.1093/restud/rdy032.

- Bhattacharya, B., I. Khadka, and D. Mani. 2022. “Shaking Up (And Keeping Intact) the Old Boys’ Network: The Impact of the Mandatory Gender Quota on the Board of Directors in India.” Journal of Business Ethics 177 (4): 763–778. doi:10.1007/s10551-022-05099-w.

- Biygautane, M., P. Gerber, and G. Hodge. 2017. “The Evolution of Administrative Systems in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar: The Challenge of Implementing Market Based Reforms.” Digest of Middle East Studies 26 (1): 97–126. doi:10.1111/dome.12093.

- Bosbait, M., and R. Wilson. 2005. “Education, School to Work Transitions and Unemployment in Saudi Arabia.” Middle Eastern Studies 41 (4): 533–545. doi:10.1080/00263200500119258.

- Callahan, J. L. 2014. “Writing Literature Reviews: A Reprise and Update.” Human Resource Development Review 13 (3): 271–275. doi:10.1177/1534484314536705.

- Central Statistical Bureau. 2016. Labor Force Survey 2015.

- Claude, B., F. Martorell, and J. C. Tanner. 2009. “Qatar’s Labor Markets at a Crucial Crossroad.” The Middle East Journal 63 (3): 421–442. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3751/63.3.14.

- Dosary, A., and S. Adel 2004. “Hrd or Manpower Policy? Options for Government Intervention in the Local Labor Market That Depends Upon a Foreign Labor Force: The Saudi Arabian Perspective.” Human Resource Development International 7 (1): 123–135. doi:10.1080/1367886022000041967.

- Elbanna, S. 2021. “Policy and Practical Implications for Workforce Nationalization in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries.” Personnel Review 51 (4): 1248–1261. doi:10.1108/PR-11-2020-0835.

- Elbanna, S., L. Hsieh, and J. Child. 2020. “Contextualizing Internationalization Decision-Making Research in Smes: Towards an Integration of Existing Studies.” European Management Review 17 (2): 573–591. doi:10.1111/emre.12395.

- Elbanna, S., S. Obeidat, H. Younis, and T. Elsharnouby. 2021. An Evidence-Based Review on Nationalization of Human Resources in the GCC Countries. Administrative Sciences Association of Canada.

- Emirates News Agency. 2019. “Sheikh Mohammed’s 10 Steps for Emiratisation; Here’s How It Affects Expats.” Khaleej Times. https://www.khaleejtimes.com/news/government/sheikh-mohammeds-10-steps-for-emiratisation-heres-how-it-affects-expats-.

- Fahad, A., and K. S. Nair. 2019. “Building the Health Workforce: Saudi Arabia’s Challenges in Achieving Vision 2030.” The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 34 (4): e1405–e1416. doi:10.1002/hpm.2861.

- Federal Competitiveness and Statistics Centre. 2019. Percentage distribution of Employed Persons (15 years and over) by Nationality, Gender and Sector.

- Forstenlechner, I. 2008. “Workforce Nationalization in the UAE: Image versus Integration.” Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues 1 (2): 82–91. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17537980810890275.

- Forstenlechner, I., M. T. Madi, H. M. Selim, and E. J. Rutledge. 2012. “Emiratisation: Determining the Factors That Influence the Recruitment Decisions of Employers in the UAE.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 23 (2): 406–421. doi:10.1080/09585192.2011.561243.

- Forstenlechner, I., and K. Mellahi. 2011. “Gaining Legitimacy Through Hiring Local Workforce at a Premium: The Case of Mnes in the United Arab Emirates.” Journal of World Business 46 (4): 455–461. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2010.10.006.

- Forstenlechner, I., and E. Rutledge. 2010. “Unemployment in the Gulf: Time to Update the “Social Contract.” Middle East Policy 17 (2): 38–51.

- General Secretariat for Development Planning. 2008. Qatar National Vison 2030. Doha.

- General Secretariat for Development Planning. 2011. Qatar National Development Strategy: 2011 2016. Edited by Planning and Statistics Authority. Doha. https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/qnv1/Documents/QNV2030_English_v2.pdf.

- Glaister, A. J., R. Al Amri, and D. P. Spicer. 2019. “Talent Management: Managerial Sense Making in the Wake of Omanization.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1–19. doi:10.1080/09585192.2018.1496128.

- Gupta, Z. S., T. Cullinan, and G. Filocca. 2021. “Expat Exodus Adds to Gulf Region’s Economic Diversification Challenges.” S&P. https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/210215-expat-exodus-adds-to-gulf-region-s-economic-diversification-challenges-11800970.

- Harrison, D., and K. Klein. 2007. “What’s the Difference? Diversity Constructs as Separation, Variety, or Disparity in Organizations.” Academy of Management Review 32. doi:10.5465/AMR.2007.26586096.

- Harry, W. 2007. “Employment Creation and Localization: The Crucial Human Resource Issues for the GCC.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 18 (1): 132–146. doi:10.1080/09585190601068508.

- Hassan, M., and T. O’Mealia. 2020. “Representative Bureaucracy, Role Congruence, and Kenya’s Gender Quota.” Governance 33 (4): 809–827. doi:10.1111/gove.12480.

- Howard, L., and N. Prakash. 2012. “Do Employment Quotas Explain the Occupational Choices of Disadvantaged Minorities in India?” International Review of Applied Economics 26 (4): 489–513. doi:10.1080/02692171.2011.619969.

- Ingo, F., F. Lettice, and M. F. Özbilgin. 2012. “Questioning Quotas: Applying a Relational Framework for Diversity Management Practices in the United Arab Emirates.” Human Resource Management Journal 22 (3): 299. doi:10.1111/j.1748-8583.2011.00174.x.

- Jabeen, F., F. Mohd Nishat, and M. Katsioloudes. 2018. “Localisation in an Emerging Gulf Economy.” Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 37 (2): 151–166. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EDI-02-2017-0045.

- Karam, A., P. Jayashree, and V. Lindsay. 2015. “A Study of Factors Affecting Employability of Emirati Nationals in the Uae Private Sector.” Journal of Management & World Business Research 12 (1): 31–47.

- Kirsch, A., V. Sondergeld, and K. Wrohlich. 2022. “While Gender Quotas for Top Positions in the Private Sector Differ Across EU Countries, They are Effective Overall.” Diw Weekly Report 12 (3/4): 32–39.

- LMRA. 2021a. Bahrain Labour Market Indicators. Labour Market Regulatory Authority.

- LMRA. 2021b. Bahrain Labour Market Indicators. edited by Labour Market Regulatory Authority. http://blmi.lmra.bh/2021/03/mi_data.xml

- Looney, R. E. 1991. “Patterns of Human Resource Development in Saudi Arabia.” Middle Eastern Studies 27 (4): 668–678.

- Maida, A., and A. Weber. 2022. “Female Leadership and Gender Gap Within Firms: Evidence from an Italian Board Reform.” Ilr Review 75 (2): 488–515. doi:10.1177/0019793920961995.

- Marchon, C., and H. Toledo. 2014. “Re-Thinking Employment Quotas in the UAE.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25 (16): 2253. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.872167.

- Marmenout, K., and P. Lirio. 2014. “Local Female Talent Retention in the Gulf: Emirati Women Bending with the Wind.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 25 (2): 144–166. doi:10.1080/09585192.2013.826916.

- Mellahi, K. 2007. “The Effect of Regulations on HRM: Private Sector Firms in Saudi Arabia.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 18 (1): 85–99. doi:10.1080/09585190601068359.

- Mensi-Klarbach, H., and C. Seierstad. 2020. “Gender Quotas on Corporate Boards: Similarities and Differences in Quota Scenarios.” European Management Review 17 (3): 615–631. doi:10.1111/emre.12374.

- Moideenkutty, U., Y. S. R. Murthy, and A. Al-Lamky. 2016. “Localization HRM Practices and Financial Performance: Evidence from the Sultanate of Oman.” Review of International Business and Strategy 26 (3): 431–442. doi:10.1108/RIBS-12-2014-0123.

- Mori, Y., and N. Sakamoto. 2018. “Economic Consequences of Employment Quota System for Disabled People: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design in Japan.” Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 48: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jjie.2017.02.001.

- Nazarov, Z., D. Kang, and S. von Schrader. 2015. “Employment Quota System and Labour Market Outcomes of Individuals with Disabilities: Empirical Evidence from South Korea.” Fiscal Studies 36 (1): 99–126. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5890.2015.12047.x.

- NCSI. 2022. Labour Market. edited by. National Center for Statistics and Information. https://data.gov.om/byvmwhe/labour-market?accesskey=jbqyjkb

- Parcero, O. J., and J. Christopher Ryan. 2017. “Becoming a Knowledge Economy: The Case of Qatar, UAE, and 17 Benchmark Countries.” Journal of the Knowledge Economy 8 (4): 1146–1173. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13132-016-0355-y.

- Pech, R. 2009. “Emiratization: Aligning Education with Future Needs in the United Arab Emirates.” Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues 2 (1): 57–65. doi:10.1108/17537980910938488.

- Peck, J. R. 2017. “Can Hiring Quotas Work? The Effect of the Nitaqat Program on the Saudi Private Sector.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 9 (2): 316–347.

- Planning and Statistics Authority. 2020a. Chapter 2. Labour Force. https://www.psa.gov.qa/en/statistics/Statistical%20Releases/General/StatisticalAbstract/2020/2_Labour_Force_2020_AE.pdf

- Planning and Statistics Authority. 2020b. Labor Force Sample Survey. The second quarter(April – June 2020). Qatar.

- Popay, J., H. M. Roberts, A. J. Sowden, M. Petticrew, L. Arai, M. Rodgers, and N. Britten. 2006. ”Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews.” A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version 1. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf

- Ramady, M. 2013. “Gulf Unemployment and Government Policies: Prospects for the Saudi Labour Quota or Nitaqat System.” International Journal of Economics and Business Research 5 (4): 476–498. doi:10.1504/IJEBR.2013.054266.

- Randeree, K. 2012. “Workforce Nationalization in the Gulf Cooperation Council States.” doi:10.2139/ssrn.2825910.

- Raven, J. 2011. “Emiratizing the Education Sector in the UAE: Contextualization and Challenges.” Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues 4 (2): 134–141. doi:10.1108/17537981111143864.

- Rees, C. J., A. Mamman, and B. Aysha Bin. 2007. “Emiratization as a Strategic HRM Change Initiative: Case Study Evidence from a UAE Petroleum Company.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 18 (1): 33. doi:10.1080/09585190601068268.

- Rutledge, E., F. Al Shamsi, Y. Bassioni, and H. Al Sheikh. 2011. “Women, Labour Market Nationalization Policies and Human Resource Development in the Arab Gulf States.” Human Resource Development International 14 (2): 183–198. doi:10.1080/13678868.2011.558314.

- Said, E., D. M. Abdelzaher, and N. Ramadan. 2020. “Management Research in the Arab World: What is Now and What is Next?” Journal of International Management 26 (2). doi:10.1016/j.intman.2020.100734.

- Schmitt, N. 2015. “Towards a Gender Quota.” Diw Economic Bulletin 5 (40): 527–536.

- Seierstad, C., G. Healy, E. Sønju Le Bruyn Goldeng, and H. Fjellvær. 2021. “A “Quota Silo” or Positive Equality Reach? The Equality Impact of Gender Quotas on Corporate Boards in Norway.” Human Resource Management Journal 31 (1): 165–186. doi:10.1111/1748-8583.12288.

- Sidani, Y., and A. Al Ariss. 2014. “Institutional and Corporate Drivers of Global Talent Management: Evidence from the Arab Gulf Region.” Journal of World Business 49 (2): 215–224. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2013.11.005.

- Swailes, S., L. G. Al Said, and A. Fahdi Saleh 2012. “Localisation Policy in Oman: A Psychological Contracting Interpretation.” The International Journal of Public Sector Management 25 (5): 357–372. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09513551211252387.

- Thompson, P., and H. Wissink. 2016. “Political Economy and Citizen Empowerment: Strategies and Challenges of Emiratisation in the United Arab Emirates.” Acta Commercii 16 (1). doi:10.4102/ac.v16i1.391.

- Tlaiss, H. A., and M. Al Waqfi. 2020. “Human Resource Managers Advancing the Careers of Women in Saudi Arabia: Caught Between a Rock and a Hard Place.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1–36. doi:10.1080/09585192.2020.1783342.

- Toledo, H. 2013. “The Political Economy of Emiratization in the UAE.” Journal of Economic Studies 40 (1): 39–53. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/01443581311283493.

- Wang, J. 2019. “Demystifying Literature Reviews: What I Have Learned from an Expert?” Human Resource Development Review 18 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1177/1534484319828857.

- Williams, J., B. Ramudu, and A. Fish. 2011. “Localization of Human Resources in the State of Qatar.” Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues 4 (3): 193–206. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17537981111159966.

- The World Bank. 2020. World Development Indicators.

- Yaghi, A., and I. Yaghi. 2013. “Human Resource Diversity in the United Arab Emirates: Empirical Study.” Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues 6 (1): 15–30. doi:10.1108/17537981311314682.

- Yoshihiko, F. 2019. “Employment of Persons with Disabilities in Sweden.” Global Business & Economics Anthology 1: 54–63.