ABSTRACT

The aim of this study is to further develop our understanding of transfer of training by introducing an additional post training transfer intervention of implementation intentions. This enhances the substantial developments made by goal setting theory but concentrates on goal achievement rather than simply goal setting. Whilst goal intentions specify what a person wants to achieve, implementation intention specifies the behaviour to be performed and the situational context it is to be performed in. This is a qualitative study based on a management development program being delivered in one UK Higher Education Institute. Data was collected from reflective learning journals and semi structured interviews with 15 participants. Findings indicate that the use of an implementation intention statement encouraged transfer in 67% of the participants. This is a higher figure than any other study not using implementation intentions, has previously recorded. This study therefore advances scholarship in the field of Human Resource Development (HRD) and especially transfer of training. It also provides practical utility for organisations looking to gain a return from their investment in HRD.

Introduction

The Higher Education (HE) sector is experiencing external challenges such as a review of tuition fees, Brexit, pension changes, and moving to blended learning which has been accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. One Higher Education Institute (HEI) in the North of England is addressing these challenges through a management development programme, delivered in partnership with the Chartered Management Institute (CMI). If successful, it will become the only organization in Europe to have its whole management body recognized as Chartered Managers.

It is accepted there is a positive relationship between managers’ skill levels and their contribution to company, national and global success (CIPD Citation2021; Rekalde, Landeta, and Albizu Citation2015). Organizations reserve one-third of training for activities relating to supervisory or management skills, however there is limited evidence concerning the effectiveness of such activity (Brown, Warren, and Khattar Citation2016; Soderhjelm et al. Citation[2020] 2021). A challenge for HRD researchers and practitioners is demonstrating the value proposition, especially in competitive, complex, and constantly changing business contexts (Hirudayaraj and Matić Citation2021) which the organization in this study currently operates in. For management development to be effective, transfer of training, defined as ‘the extent to which, what is learned in training is applied on the job and enhances job related performance’ (Laker and Powell Citation2011, 1) must take place. This is not something that only affects management development programmes though. Internationally, organizations spend billions of dollars on training and development annually with the expectation of improved performance (Kim, Park, and Kang Citation2019; Na-Nan and Sanamthong Citation2020). Despite this, the impact on performance varies considerably.

The purpose of this study is to consider the impact of the management development programme on performance. It will investigate whether a post-training transfer intervention will encourage managers to change their behaviour and incorporate new strategic tools, introduced during the programme, into their work roles. Whilst relapse prevention and goal setting theory are the dominant post-training interventions (Rahyuda, Syed, and Soltani Citation2014), goal setting theory has provided more empirical data. However, it has still not fully accounted for goal completion.

The uniqueness of this study is to incorporate implementation intentions as a post-training transfer intervention to build on the success of goal setting theory. Whilst goal intentions specify what a person wants to achieve, implementation intentions specify the required behaviour and identify the situational context in which it is to be performed (Sheeran, Webb, and Gollwitzer Citation2005). Implementation intentions specify when, where and how goal directed responses should be initiated. The specific research question is,

R1:

How does using an implementation intention turn goal directed behaviour into action and foster transfer of new knowledge and skill to the manager’s job role?

With such an ambitious programme it is imperative that the status of Chartered Manager does not obscure the performance of the managers after taking part in the programme. Ensuring that managers transfer the skills and knowledge gained as well as receiving the accreditation is therefore important from an academic and a practical perspective.

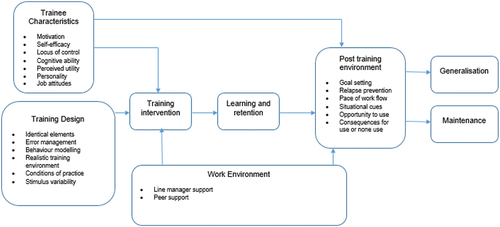

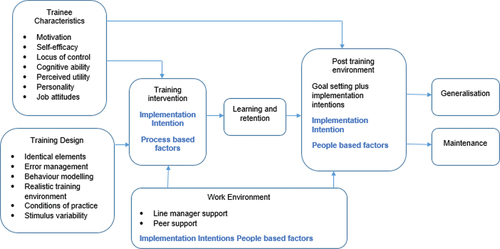

The paper makes two contributions to the HRD literature and community of practice regarding transfer of training. First, a conceptual model () is proposed which highlights what is currently known about the landscape from a theoretical perspective. It should be stressed this is not a systematic literature review but a heuristic representation of the incremental developments in the field. highlights the theoretical contribution of the paper by demonstrating how the current landscape can be developed to incorporate implementation intentions as an alternative post-training transfer intervention. Only one study (Friedman and Ronen Citation2015) has specifically considered implementation intentions with transfer of training. No other study has therefore created this platform for researchers to further develop an understanding of the transfer of training.

The second contribution is to provide empirical evidence with regard to operationalizing this conceptual model. Relapse prevention is an accepted post-training transfer intervention but is criticized for the lack of empirical evidence (Burke Citation1997; Gaudine and Saks Citation2004; Rahyuda, Syed, and Soltani Citation2014). For implementation intentions to gain currency, it is vital that data underpin the success. Hopefully, the findings from this paper will generate intrigue and curiosity in other researchers to develop this empirical base further. Providing a different theoretical but evidence-based concept will offer practitioners the confidence that HRD interventions supported by implementation intentions can improve performance and justify their HRD activity.

The paper first reviews the history to date of studies into transfer of training. A critical evaluation of implementation intentions to understand the potential to enhance transfer of training follows this. Next, the methodology section explains the research design, study participants, data collection, and data analysis. The findings and discussion will consider the initial impact of using implementation intentions before identifying practical implications and a future research agenda.

Transfer of training input factors

Interest in transfer of training increased in the 1980s (Bell et al. Citation2017) and heralded one of the first major reviews, by Baldwin and Ford (Citation1988). This identified three key factors which affected transfer: training inputs, training outputs and conditions of transfer. Training input refers to trainee characteristics, training design and workplace environment with Hart, Steinheider, and Hoffmeister (Citation2019) suggesting all three must function collaboratively. Training outputs refer to learning and retention of material and conditions of transfer refer to short-term generalization or long-term maintenance.

Initially, empirical investigation of trainee characteristics was limited (Baldwin and Ford Citation1988; Cheng and Ho Citation2001). Further study has, however, identified numerous characteristics such as locus of control (Cheng and Ho Citation2001); personality, (Burke and Hutchins Citation2007); cognitive ability (Huang et al. Citation2015; Keith, Richter, and Naumann Citation2010), perceived utility, (Chiaburu and Lindsay Citation2008; Chung, Gully, and Lovelace Citation2017; Grossman and Salas Citation2011); job attitudes and motivation (Renta et al. Citation2014). Self-efficacy and motivation are pre-eminent characteristics which affect transfer.

Self-efficacy relates to the trainees’ confidence in their capabilities to learn the content of the training and their confidence and capability to transfer what they have learned, (Weisweiler et al. Citation2013). Trainees with higher self-efficacy often have more confidence in their ability to perform a given task (Na-Nan and Sanamthong Citation2020) whilst those with low self-efficacy are more likely to lessen their effort especially under increased pressure (Grossman and Salas Citation2011; Quinones Citation1995). High self-efficacy should not always mean transfer is guaranteed though. Vancouver and Kendall (Citation2006) found high self-efficacy could cause individuals to feel they are fully equipped for future challenges so reduce their effort. Training motivation is the intensity and persistence of efforts that trainees apply in learning orientated improvement activities, before, during and after training (Ali, Tufail, and Kiran Citation2022; Tannenbaum and Yukl (Citation1992). Gegenfurtner (Citation2020) identified autonomous motivation, governed by the self and controlled motivation which is regulated by external rewards or sanctions. Twase et al. (Citation[2021] 2022 identify a person’s response to behavioural interventions such as training as a conscious outcome of intrinsic and extrinsic motivating factors held regarding the behaviour. Other studies (Brinkerhoff and Montesino Citation1995; Chauhan et al. Citation2016; Facteau et al. Citation1995) indicate that pre- and post-training conversations can increase motivation, which positively affects transfer. Measures of transfer motivation have received critique, however, for mostly being assessed on a one-dimensional construct (Sahoo and Mishra Citation2019).

Training design initially concentrated on learning principles such as identical elements, teaching of general principles and stimulus variability. Newer concepts have since been identified. Behaviour modelling suggests that people can learn vicariously through observing the experiences of others (Murthy et al. Citation2008). Positive and negative behaviour modelling have been identified as most effective rather than use of only one (Taylor, Russ-Eft, and Chan Citation2005). Error management allows trainees to make errors, before being given error management instructions which teach them how to cope with the situation (Ran and Huang Citation2019). Attention also focussed on the conditions of practice such as whether the objectives are clearly communicated and understood and whether participants have been involved with designing the intervention (Martin Citation2010). A realistic training environment is now considered to be important where aspects of training should mirror the environment in which trained skills and competencies will be applied (Grossman and Salas Citation2011). The greater understanding of trainee characteristics and design principles have been accompanied by a greater understanding of the role played by the work environment.

Three sources of work support have been identified as organizational, supervisory and peer (Hughes et al. Citation2020). These can further be categorized into work system factors and people factors (Lim and Johnson Citation2002). Work system factors are pace of workflow, cues to prompt trainees and consequences for using training on the job, (Burke and Hutchins Citation2007; Cheng and Ho Citation2001; Martin Citation2010). Employees with extensive opportunities to practice and apply new knowledge and skills will outperform those who do not have these opportunities (Wei, Amy, and Gamble Citation2016). Work system factors sit at the organizational level and the cultural understanding of HRD interventions.

People related factors consider line manager and peer support and these have received more attention than work system factors. Line manager support is considered one of the most powerful tools for enhancing transfer (Burke and Hutchins Citation2007; Islam and Ahmed Citation2018; Kim, Park, and Kang Citation2019; Nijman et al. Citation2006). Managers can offer support through discussing what has been learned in training, offering recognition, participating in training themselves, providing encouragement and coaching, and modelling trained behaviours (Burke and Hutchins Citation2007; Grossman and Salas Citation2011; Lancaster, Di Milia, and Cameron Citation2013). Evidence also suggests that the absence of support has a negative effect on employees and leaves them feeling frustrated (Clarke Citation2002; Greenan Citation2016). Peer support enhances transfer by improving employee’s feelings of self-efficacy and providing them with coaching and feedback (Martin Citation2010).

Continuous study has therefore advanced the knowledge of how input factors affect transfer of training. Studies have also unearthed what might affect transfer after the training intervention has been delivered in what is known as the post-training environment.

Post training environment

Two dominant post-training transfer interventions are relapse prevention and goal setting theory (Rahyuda, Syed, and Soltani Citation2014). Relapse prevention was introduced to the literature by Robert Marx in 1982 (Burke and Baldwin Citation1999; Gaudine and Saks Citation2004). Marx identified seven steps to what has become known as the full or complete RP model (see Burke and Baldwin Citation1999 for a breakdown of these steps). Researchers using some of the seven steps are considered to use a modified RP model (Burke and Baldwin Citation1999; Rahyuda, Syed, and Soltani Citation2014). Limited success has been found for both full and modified RP models.

Goal setting theory has developed a more empirical base. People who set and commit to specific and difficult goals outperform those who set vague goals (Brown, McCracken, and Hillier Citation2013) because specific and difficult goals give focus and direct attention to activities relevant to attaining the goal (Seijts and Latham Citation2012). Brown and McCracken (Citation2010) uncovered four types of goals: learning goals, outcome/performance goals, distal goals, and proximal goals. Learning goals are used by individuals striving to understand something new or increase their level of competence (Button, Mathieu, and Zajac Citation1996; Narayan and Steele-Johnson Citation2007). Outcome or performance goals are associated with individuals striving to demonstrate their competence via task performance (Button, Mathieu, and Zajac Citation1996; Narayan and Steele-Johnson Citation2007) and are more associated with transfer of training (Chiaburu and Tekleab Citation2005). Distal goals are long-term goals, whereas proximal goals are more short-term or sub goals (Seijts and Latham Citation2001). Studies (Brown Citation2005; Weldon and Yun Citation2000) indicate that proximal plus distal goals lead to greater performance than distal goals alone. They allow people to evaluate their ongoing goal directed behaviour and refocus their efforts if needed (Brown Citation2005; Seijts and Latham Citation2001; Weldon and Yun Citation2000). This creates a sense of immediacy, provides a clear mark of progress, and leads to a sense of mastery whilst allowing the distal goal to be recalibrated if needed (Weldon and Yun Citation2000).

Mediators to goal achievement have been identified such as viewing the goal as important, task complexity, situational constraints, feedback, and commitment to the goal (Bipp and Kleingeld Citation2011; Ilies and Judge Citation2005; Locke and Latham Citation2006). Hollenbeck and Klein (Citation1987) identified several situational factors which could impact goal commitment such as publicness (are significant others are aware of the goal); volition (the extent to which an individual is free to engage in behaviour) and explicitness (as opposed to vague goals being set). All goal setting is more effective when people participate than when goals are assigned to them (Li and Butler Citation2004; London, Mone, and Scott Citation2004).

The paper has so far presented a heuristic overview of studies since Baldwin and Ford’s (Citation1988) seminal framework. Today, this framework is only a skeleton of what is known. provides a contemporary framework which takes account of the pre and post-training environment. Generalization which refers to the extent to which knowledge and skills are applied to different settings in the workplace and maintenance, which refers to the timescale in which transfer persists (Brown Citation2005) are still as relevant as in the original framework.

The current study aims to develop by addressing the transfer of training from a new perspective which is to use implementation intentions as the means to turn goal setting into goal achievement. The following section will outline what implementation intentions are and review findings of studies to date.

Implementation intentions

The origins of implementation intentions are in psychology and medicine and based on the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen Citation2002). According to the TPB the determinant of behaviour is intention. Three considerations guide human actions; behavioural beliefs (concerned with the consequences of behaviour); normative beliefs (concerned with the normative expectations of others) and control beliefs (concerned with the presence of factors that may facilitate or impede performance). Together, they lead to the formation of a behavioural intention which creates a mental link between a selected cue or situation and a goal directed response. The goal directed response is performed as soon as the specified situation is encountered (Achtziger, Gollwitzer, and Sheeran Citation2008).

Success for implementation intentions has been identified by people taking vitamin C tablets (Sheeran and Orbell Citation1999), initiating functional activities after orthopaedic surgery (Orbell and Sheeran Citation2000), attendance at further treatment following drug and alcohol detoxification (Kelly et al. Citation2016) and reducing binge drinking (Norman, Webb, and Millings Citation2019). Each of these studies indicated greater levels of goal achievement when accompanied by an implementation intention.

Studies outside of medicine also indicate higher goal achievement when accompanied by an implementation intention. One study (Gollwitzer and Brandstätter Citation1997) asked students to answer a questionnaire about their personal goals and indicate whether they had formed implementation intentions as well. Results found that difficult goals with an implementation intention were completed in 62% of cases, whereas those without an implementation intention were only completed in 22% of cases. Four separate studies formed the basis of one further investigation by Brandstätter, Lengfelder, and Gollwitzer (Citation2001), two with medical patients and two with students. All four studies indicated that forming implementation intentions had a beneficial effect on the initiation of goal directed behaviour.

A study in a telecom firm in the Netherlands (Holland, Aarts, and Langendam Citation2006) saw implementation intentions help them accomplish a higher profile recycling culture. Results of this study found that conscious planning through implementation intentions broke old habitual behaviour and created new habits. Those in the control group with implementation intentions began to use central recycling bins more than their own wastebaskets. Planning where, when, and how to recycle led to more people doing it.

The success lies in understanding that achievement of goals requires action and implementation intentions commit a person to goal-directed action once the critical situation is encountered. The situational cue must remain constant, it is the behaviour which changes to affect improved performance (Holland, Aarts, and Langendam Citation2006).

Whilst examples have been provided of implementation intentions affecting goal directed behaviour in a variety of settings, very few studies have considered implementation intentions and transfer of training to the workplace. Friedman and Ronen (Citation2015) studied 65 trainees on two different training programmes. One of these programmes focussed on sales supervisors who formed implementation intentions after sales training. Performance on this study was measured four weeks after the end of the training. Mystery shoppers assessed supervisors on a behavioural anchored rating scale. Those who formed implementation intentions provided the trained response on average seven times out of ten whereas those who did not form implementation intentions provided the trained response on average four times out of ten. Gegenfurtner and Testers (Citation2022) tested TPB on non-traditional students’ intentions to transfer knowledge from a university course to their workplace. This study found that transfer attitudes were most strongly associated with transfer intentions.

Greenan, Reynolds, and Turner (Citation2017) note that implementation intentions must take account of both process-based and people-based factors. Process based factors consider the training intervention itself. Training objectives, goals and implementation intentions must be considered at the intervention design stage. Trainees should understand the implementation intention and required behaviour change before the end of the training. Participants must have clear plans specifying when, where, and how the goals are to be achieved to ensure their effective implementation. People-based factors consider key stakeholders involved in pre- and post-training activities, most notably the trainer and line manager. A supportive work environment akin to that already discussed is therefore still a requirement for the implementation intention to be successful.

Whilst provides the heuristic picture to date, introduces the potential new development which is one of the contributions of this paper. It provides a theoretical framework for researchers to base future study on by incorporating the process and person-related factors linked to implementation intentions. The visual representation helps to envisage what the theory will look like in practice and has guided the current study.

Before presenting the findings, the research methodology will be considered.

Methodology

Research philosophy

Two fundamental categories of existence (Bueno, Busch, and Shalkowski Citation2015). The ontology-first approach seeks to identify things the way they are. Reality is external to individual consciousness (Palagolla Citation2016) and facts seem to be ontologically indispensable as truth makers (Lowe Citation1998). The representation-first approach studies the features of reality and their associated limitations. It acknowledges the things researchers observe are socially constructed (Palagolla Citation2016) and individual perceptions create reality.

Most studies into transfer of training are quantitative (Brown, McCracken, and O’kane Citation2011; Yang et al. Citation2020) so follow the ontology-first approach and this may provide a narrow focus. This current study is a qualitative inductive one, so adopts the representation-first philosophy. As such it addresses calls for more qualitative research in Human Resource Development. Gubbins et al. (Citation2018) notes there is considerable scope for improvement in research methodologies in the HRD field and Anderson (Citation2017) identifies an increasing call within HRD for in-depth qualitative research to enhance the evidence base associated with the field. Qualitative methods have been used to study transfer of training (Brown, McCracken, and O’kane Citation2011; Johnson, Blackman, and Buick Citation2018; Lancaster, Di Milia, and Cameron Citation2013), although not overwhelmingly. This paper seeks to further establish this method as an acceptable mode of study. As an inductive study, no hypotheses are presented but themes will be identified which researchers could develop in other studies.

Research design

Case study research is defined as ‘the intensive (qualitative or quantitative) analysis of a single unit or small number of units (the cases), where the researcher’s goal is to understand a larger class of similar units (a population of cases), (Seawright and Gerrin Citation2008, 296). It is born out of the desire to understand complex social phenomena (Yin Citation2014) and allows investigation of the ‘hows’ and ‘whys’ of a phenomenon within a real-life context. It is a valid research method which produces knowledge relevant to both theory and practice (Schiele and Krummaker Citation2011). As this study only used participants from one organization it constitutes a case study but is an appropriate method given the research question asks ‘How does using an implementation intention turn goal directed behaviour into action and foster transfer of new knowledge and skill to the manager’s job role?

Case study research is often accused of lacking rigour as it has not followed systematic procedures (Yin Citation2014). The procedures followed in this study have been systematic whilst working with text rather than numbers. Similarly, it has limits with regard to generalizability and is subject to the researcher’s bias (Flyvbjerg Citation2006; Schiele and Krummaker Citation2011). Bias has been avoided as far as possible through adapting to participant responses, which will be explained in the data collection section. Transfer of training is a worldwide phenomenon with studies taking place in USA (Martin Citation2010), Canada (Brown, Warren, and Khattar Citation2016), Greece (Diamantidis and Chatzoglou Citation2014), Portugal (Curado, Lopes Henriques, and Ribeiro Citation2015), Australia (Johnson, Blackman, and Buick Citation2018) and Malaysia (Zumrah and Boyle Citation2015) to give some examples. Whilst not generalizing from the results, the potential impact of this case study could be to encourage academics in this global network to extend their research and develop the empirical evidence this paper seeks to initiate. Whilst this would satisfy a theoretical contribution, practical utility will be gained through those research organizations benefitting from greater impact of their HRD interventions on performance. The study therefore has relevance and implications for HRD researchers and practitioners.

Organisational agreement

Agreement for the study to be conducted was gained from the Vice Chancellor of the HEI and the Head of People Development whose team delivered the programme. The process-based considerations of were considered as the programme launch was attended to explain what implementation intentions are and how they are being considered in this programme. Action learning sets took place at the start of the programme. All of these were attended to explain what the specific implementation intention statement was. The first part of the programme considered the University strategy map, so the implementation intention statement was,

When I discuss the strategy map with my team, I will consider the strategic tools discussed on the program.

Research participants

Appropriateness and adequacy determine sampling methods for qualitative research (O’reilly and Parker Citation2013). Everyone on the current cohort was a manager so a sample of these would be appropriate to address the research question. No exclusion criteria applied as manager was the key variable. There were 115 people in total on this cohort, with management responsibility for either academics or support function staff. Each manager was contacted by email to see if they would participate in the study. An information sheet and participant consent form were attached to the email. Sixteen people returned a completed consent form which provided a representative sample across all schools and services. Of these, nine were female and seven were male but there was an equal split of eight academic managers and eight support function managers. This differentiation has allowed for comparison between these groups to provide the organization with more nuanced information.

Smaller sample sizes are accepted in qualitative studies. Lim and Johnson (Citation2002) involved 10 HRD practitioners, Martin (Citation2010) used 12 managers, Clarke (Citation2002) involved 14 trainees, Soderhjelm et al. Citation([2020] 2021 interviewed 12 leaders and Griggs et al. (Citation2018) interviewed 18 HR professionals. A sample of 16 managers therefore meets the test of adequacy (O’reilly and Parker Citation2013) through comparison to previous studies focusing on management development or transfer of training.

Data collection

There were two phases of data collection with the first utilizing reflective learning journals (RLJ). Participants were encouraged to reflect on the implementation intention statement once the situational cue (discussing the strategy map) arose. Goal-directed behaviour was using new strategic tools which they had been introduced to, so addressing the situation in a different way. Given there is no way of predicting when the situational cue would arise there could be numerous RLJ’s on the same day or none for a week.

Semi-structured interviews formed the second phase of data collection. Of the 16 participants who agreed to complete an RLJ, 15 agreed to be interviewed. Eleven interviews took place over an initial two-month period. As the number of interviews increased, new themes began to emerge which were followed up in subsequent interviews. Whilst this moving of the goalposts may be considered poor practice by quantitative researchers, it is considered good qualitative practice (Ziebland and McPherson Citation2006). This ability to move with the data helped to reduce potential bias as the direction of the conversation and by inference each participant guided subsequent conversations.

A further three interviews took place one month later which allowed for the possibility that new patterns may emerge as respondents who had not yet been interviewed had more time to reflect. Responses from these interviews fitted into the same themes. One further interview was conducted another month later but again the same responses were being offered. Analytic memos were written after each interview which helped make sense of the information provided and identify the emerging patterns (Lawrence and Tar Citation2013).

Each interview was pre-arranged and took place in a quiet setting such as the respondents’ office, consistent with DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree (Citation2006). All interviews were recorded using an iPad app and saved on ‘Google Drive’ which can only be accessed with a secure password, so privacy of data was maintained. The questions were pre-determined but open ended which allowed for other questions to emerge from the dialogue, again consistent with DiCicco-Bloom and Crabtree (Citation2006).

Data analysis

All interviews and analytic memos were self-transcribed then imported into an NVivo software package for storage, coding, and analysis. Coding both the transcript and analytic memo has allayed some of the concerns of Li (Citation2022) who notes that researchers only analyse participant responses while failing to account for how they contributed to the production of the data. Analysing both the transcript and analytic memo has therefore increased the robustness of the data. Thematic analysis was used as it provides a flexible approach and can be modified to examine the perspectives of different participants (Braun and Clarke Citation2006; Nowell et al. Citation2017). It was useful in this study as the sample could be separated dependent on managerial focus which was either academic (tutors) or support staff (HR, wellbeing, estates, admin, IT).

Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six steps to conducting thematic analysis were followed to analyse the data. Step 1, familiarization with data was through transcription of interviews and analytical memos. Step 2, generation of initial coding was developed using template analysis which is widely used in organizational and management research (Brooks et al. Citation2015; McDowall and Saunders Citation2010; Robson and Mavin Citation2014) so is appropriate for this study. Step 3, searching for themes arose out of the first phase coding. Individual nodes in NVivo were grouped together into preliminary themes. Step 4, reviewing themes to see if they work. The theme became the parent with the initial nodes now existing as child nodes so there was a trail as to how the theme had developed. This is represented in below. Step 5, defining and naming the themes was completed with reference to the theoretical background of transfer of training and implementation intentions cross-referenced with the research question. Step 6 is the writing of the paper. Whilst these six steps provide a respected and structured way to code data and generate themes, additional coding validity was sought at step 2.

Table 1. Child nodes and their description within the theme ‘situational awareness’.

Table 2. Child nodes and their description within the theme ‘productive reflection’.

Table 3. Child nodes and their description within the theme ‘transfer of training’.

Coding validity

A word frequency query can be used as a form of semi-automated coding (Bazeley and Jackson Citation2013). This query was used as a retro fitting tool in this study. All transcripts were combined into one document on which the query was run. The specific query asked for the top fifty words with length of five letters or more and to include synonyms. Five words or more helped to eliminate short connective words such as the, and/or is. The search gave confidence that the words generated were visible within the identified codes and themes so providing credibility, dependability and confirmability identified by Nowell et al. (Citation2017) as being paramount to trustworthiness in qualitative research. The structured six-step process and validation of the first-phase codes allowed for three main themes to emerge which will be discussed in the next section.

Findings

The data collection methods will be considered separately. Direct quotes provide contextual understanding and support the interpretation of the participant’s voice. indicate how first-phase child nodes have been aggregated into the main themes following Braun and Clarke’s second and third steps.

Reflective learning journals

The intention of the reflective learning journal (RLJ) was that respondents would reflect immediately when the situational cue arose. They could identify whether they had used prior habitual behaviour or new behaviour based on the material they had been introduced to during the management development programme. Despite several requests after the assignment submission date only one person provided a half completed RLJ which offers no meaningful data on which to base any conclusions. Eight people sent an email by way of apology or just to say they had not kept any journals. The biggest barriers to not completing any RLJs were time and pressure. PT003 comments represent the majority; Although it is a poor excuse work pressure and inability to put time away to enter learning journals is the reason, I didn’t manage to produce any of these.

These results are disappointing but semi-structured interviews delved deeper into whether reflection in any form could support the use of implementation intentions. It may be the timing of the reflection which is critical.

Semi structured interviews

Thematic analysis of the interview transcripts identified three themes as follows.

Theme one: situational awareness

The situational context was how the participants’ team or department implemented the university strategy map. The situational cue was discussing the strategy map with the team or department. The required behaviour was to use strategic models and tools from the development program. provides a breakdown of the codes which generated this theme.

Most participants discussed completing the assignment where they referred to the tools from the programme such as SWOT or cultural web. This indicates the situational context and cue were a focal point and addressing these through the work-based assignment was a deliberate act. Integrating the situational cue into the work-based assignment has forced participants to look closely at the strategy map within their context. RESN responded; I’m fully aware of the strategy map, we’ve all got copies of it which is given when we started and we’ve all got them pinned up on our desk and you do look at them because it’s there but did I really understand it, probably not so I guess the programme for us has really made us look at it and I think now that we understand it a lot more.

Comments such as this ratify the strength of the situational cue but the important consideration with regard to transfer of training is whether new behaviour has been used. RESA indicates that some of the new tools provided on the development programme have been utilized; the way I sort of worked at it was in terms of the assignment I’d do some of the work and I’d get my team involved and we’d use some of the tools and then I’d spend snippets of time doing the assignment. RESI also confirmed these tools have been applied to their situational context; also a good understanding of the current strategy when you went through it piece by piece and I think the actual assignment kind of got you to do that bit more and the models were quite interesting to kind of use those a bit more effectively than you would kind of generally from just looking at the strategy.

A clear situational cue therefore appears to be a focal point to trigger newly trained skills and behaviour. A group query run through NVivo () allows this association to be visualized and emphasizes the link between the situational cue and positive transfer of training.

Figure 3. Group query, situational cue, situational context, increased knowledge of the strategy map, assignment completion and positive transfer.

Whilst contains a lot of information, it shows many positive associations between the situational cue (strategy alignment) and increased knowledge of the strategy map in general, along with completing the work-based assignment. This incorporates use of strategic tools, indicating positive transfer.

Theme two: productive reflection

Immediate reflection on the situational cue and subsequent behaviour has not happened. Semi structured interviews delved deeper into whether productive reflection on the situational cue at a later stage could reinforce it. provides a breakdown of the codes which generated this theme.

Whilst immediate and self-directed reflection has not happened, subsequent planned reflection may be possible. This reflection needs to be compulsory and prompted though for it to take place. RESK noted; if we knew there was a session where perhaps we were going to have a discussion about, ok reflecting on what’s been done and what we’ve learned and how have we used anything, those things you’d probably be more likely to do it because you knew that you were going to have to talk about it. RESI noted; I think it’s kind of, I think in my mind if I think it’s compulsory or it’s something that needs to be done, I’d have it at a higher kind of level.

This summative reflection may be verbal or written but helps the employee to consider the situation that occurred and whether they used newly trained knowledge or skill to address it. Written reflection might function as a greater prompt especially if the situational cue is written to support any discussion. Reflection on past behaviour can lead to altered behaviour in future instances. RESG notes; it was after, when I realized, I’d tackled the situation in a different way than I would have previously done, I wanted to reflect on why that might have been, so I used it in that way.

Another group query () emphasizes the link between planned summative reflection and positive transfer of training.

Theme three: transfer of training

Transfer of training is evident if participants referred to the strategic tools introduced in the development programme when addressing the situational cue of discussing the strategy map. provides a breakdown of the codes which generated this theme.

In total, ten of the fifteen participants indicated they used the strategic tools from the development programme in their work role, so demonstrating positive transfer. RESA noted; it’s highlighted a number of tools that I wouldn’t have used before and it’s probably something I would use again. RESI commented; I think we used quite a lot of the bulk, kind of main ones that were there and that kind of linked to the assignment that was focussed on like the PESTLE and SWOT analysis.

Findings so far indicate generalization (Brown Citation2005) has happened. Maintenance considers whether the new behaviour change occurs over time and the study has found evidence that longer term considerations are present. RESA explained, so we had a team meeting each month and then what we did is we used that time to actually go through the cultural web. RESE observed, basically it’s going to be used to develop the plan for the service it will be used for consultation, and I’ll be able to use that material for instance when people ask me questions.

Negative transfer relates to no changes in behaviour because no learning has taken place or learning has taken place but not been applied (Grossman and Salas Citation2011). Negative transfer was evident in the sample. RESM stated, I didn’t particularly understand how the strategic analysis tools helped me within this project. I used it but couldn’t really adapt it to my working life and found it of no significance since. RESB noted, What I do, it’s in a sense more operational than strategic. Reasons for not adopting the new strategic tools may be lack of motivation or low self-efficacy. It might also be due to the already identified barrier of lack of opportunity to use new behaviour. RESB might not have been in the right role to make strategic decisions. More comments were attributed to positive transfer than negative transfer which suggests the implementation intention statement of When I discuss the strategy map with my team, I will consider the strategic tools discussed on the programme, has had some impact.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate whether a post-training transfer intervention of an implementation intention statement would encourage managers to change their behaviour and incorporate new strategic tools into their work roles. Theme three, which identified whether positive transfer of training occurred suggests it has done this. Results indicate 67% of respondents had used some of the strategic tools from the management development programme in their work role. Previous studies measuring the impact of performance varied widely. Some suggest as little as 10% is successful in improving performance (Cheng and Ho Citation2001; Grossman and Salas Citation2011; Velada et al. Citation2007; Wexley and Baldwin Citation1986). Brinkerhoff and Montesino (Citation1995) refer to no more than 20%. Banerjee, Gupta, and Bates (Citation2016), Bhatti et al. (Citation2013) and Chauhan et al. (Citation2016) all refer to the same source (Wexley and Latham Citation2002) which identified 40% transferring immediately, 25% after 6 months and 15% after 12 months. Nikandrou, Brinia, and Bereri (Citation2009) and Zumrah and Boyle (Citation2015) both refer to a study by Saks and Belcourt (Citation2006) where they identified 62% transferring initially, 44% after 6 months and 34% after 12 months. That 67% identified positive transfer in this study is therefore encouraging and commensurate with the 70% identified in the Friedman and Ronen (Citation2015) study. These two studies which looked at the use of implementation intention have therefore given grounds for optimism that other researchers could develop further.

Accepting therefore that the implementation intention statement has led to positive transfer, the research question asks how does it turn goal directed behaviour into action? The answer lies in the strong situational cue which creates awareness for when the newly trained behaviour should be used. The first unit on the management development programme lasted for three months with an assignment submitted at the end. This deadline forced participants to constantly consider the situational cue for this three-month period and adopt new material into their work practice to be able to write about it. Building this situational cue into the management development programme, in keeping with the recommendations by Greenan, Reynolds, and Turner (Citation2017), has therefore provided context for when new behaviour should be displayed and led to transfer of training.

Giving greater context to the situation has given the learning input more meaning and allowed learners to tie the required behaviour change to the moment when it should be performed. Participants in this study have testified to the effectiveness of this but the assignment has also helped to keep this situation alive. RESI notes they developed a good understanding of the current strategy when you went through it piece by piece and I think the actual assignment kind of got you to do that bit more. Not every HRD intervention will have an associated assignment, but this could be substituted with visual cues in the workplace to strengthen the situational awareness. This worked well for Holland, Aarts, and Langendam (Citation2006) who placed eye catching personal recycling boxes on employees’ desks to remind them that wastepaper and cups did not go in the general waste. This led to greater behaviour change over time. There is precedence, therefore, that creating a strong situational awareness, along with constant verbal and visual cues encourages application of new knowledge and skill to the job role and fosters behaviour change. This supports the findings of previous studies regarding work system factors (Lim and Johnson Citation2002) which consider pace of workflow, cues to prompt trainees about what they have learned and consequences for using training on the job, (Burke and Hutchins Citation2007; Cheng and Ho Citation2001; Martin Citation2010). The organization must therefore take some responsibility for enhancing transfer and not leave it to the employee alone.

The study has also determined there still needs to be support for employees to transfer new knowledge and skills. Setting an implementation intention statement and creating the situational cue are not sufficient on their own. Findings from the reflective learning journal (RLJ) were disappointing and support the notions that work is busy and reflection can be complex and confusing (Gray Citation2007; Walsh Citation2009). It seems that performance matters more than reflection on this performance (Nesbit Citation2012). Theme two identified an unexpected finding but one which aligns with the notion of verbal and visual cues. Semi-structured interviews indicated that reflection was a useful tool in supporting transfer, but subsequent summative reflection would more likely occur than immediate reflection when a situational cue arose. It might therefore be the timing of using the RLJ which is the barrier, not the willingness to use it.

RLJ’s have been used to study transfer to better effect by Brown, McCracken, and O’kane (Citation2011). Guidance around what to reflect on was offered to participants in their study as was the case in this study. Whilst completion of the RLJ in their study was voluntary, it was required to receive a Certification of Completion. Completion of the RLJ in this study was also voluntary but there were no consequences for non-completion. Building completion of RLJ’s into the programme and a requirement to submit these prior to the achievement of each unit may therefore overcome the reluctance to reflect on the situational cue as it arose.

Whilst immediate reflection on the situational cue proved to be difficult, the possibility of subsequent reflection is possible. Self-directed reflection also proved to be difficult but supported reflection initiated by a third party such as a line manager can function as a catalyst to revisit the situational cue. This realization supports the findings from previous studies about motivation to transfer. Gegenfurtner (Citation2020) identified autonomous and controlled motivation and Twase et al. Citation([2021] 2022 highlighted a person’s response to behavioural interventions such as training as a conscious outcome of intrinsic and extrinsic motivating factors.

The controlled and extrinsically supported reflection is congruent with previous studies which focussed on the work environment and line manager support which is identified as one of the most powerful tools for enhancing transfer (Burke and Hutchins Citation2007; Nijman et al. Citation2006). Some of the supportive behaviours displayed by line managers are discussing new learning and providing encouragement (Grossman and Salas Citation2011). Demonstrating these behaviours will allow the line manager to discuss the implementation intention statement. In this way productive reflection will be key to keeping the situational cue in the mind of the employee and regular and constant reflection can support maintenance.

Reasons given for not reflecting immediately were time and/or work pressure but participants acknowledged that if they knew they had to discuss something it would take a higher priority. Building reflection into the performance management process and post-training discussions could be a way to negate these barriers. This would function as a verbal cue to focus attention on the new behaviour required. This study therefore highlights that incorporating the implementation intention statement as a discursive topic can help to target the post-training support more effectively.

Implementation intentions alone cannot therefore promote positive transfer. They can with cooperation from two organizational actors though. Firstly, organization practices need to create the situational cue and allow employees the opportunity to practice and apply new skill and knowledge when this cue arises. This is important for improved performance (Wei, Amy, and Gamble Citation2016). Secondly, line manager support is vital. Whilst immediate reflection on the situational cue might not happen, summative planned reflection encouraging the employee to think about the behaviour displayed to address the situational cue is necessary. The implementation intention statement provides a specific discussion point to identify whether positive or negative transfer has occurred.

Practical implications

The paper has identified where current research on transfer of training lies and has discussed the opportunities that implementation intentions could offer with regard to future development. It serves as an invitation to researchers to pursue this further, but this cannot be accomplished without support from members of the community of practice, i.e. line managers and HRD practitioners. Successful involvement of these two groups is dependent on two factors.

Firstly, supported reflection by the line manager has been identified as key to focusing on the situational cue and the behaviour used to address this. This would naturally fit in the performance management process as frequent evaluations and interactions will ensure that both the line manager and the employee are aware of each other’s goals (Rubin and Edwards Citation2020). However, the role of performance management has been questioned. Maley (Citation2014) argues that one reason for the failure of performance management is the degree of emphasis on short-term financial goals and neglect of broader and longer-term human, social and environmental goals. Performance management also receives criticism for being something that managers ‘do’ to employees (Pulakos et al. Citation2015). A study by Cornerstone (Citation2020) identified that amongst the most cited obstacles to performance management happening were limited coaching skills and the inability of managers to build actionable performance goals. The first practical implication therefore is that further line manager training is required with regard to supporting employees post training but specifically in setting goals and action plans to achieve them. Organizational performance management processes may also need to be reviewed to allow for time to hold regular reflective conversations.

The second implication relates to those who deliver HRD interventions. Previous studies (Brinkerhoff and Montesino Citation1995; Burke and Hutchins Citation2007; Martin Citation2010) advocate a partnership approach to HRD which is welcome but all parties in the partnership require the same understanding. With the implementation intention being introduced at the start of the intervention (Greenan, Reynolds, and Turner Citation2017), those responsible for delivering it must have input into the implementation intention statement and must design the intervention with this in mind. The unique practical contribution of this paper is to begin to collect empirical data to swell the body of evidence in support of implementation intentions. To do this, training and development will be needed for those who are expected to design and deliver HRD solutions on which research is conducted.

Limitations and future research agenda

Despite the context-specific nature of this case study, it has provided insight into the potential that implementation intentions could have for enabling transfer of training. Considering this, the following directions for future research are proposed.

First, the findings of this study are aimed at one specific organization and industry, so generalizability is not sought. Future research should, however, look to replicate this study in different organizations and industries on a global basis to build up a stronger base level of support.

Second, the study was based on a management development programme and one specific aspect which focussed on the softer skill of communication. Keith and Frese (Citation2008) have highlighted the differences between technical skills, social skills and management skills and the need to test their theory in each of these to gain a deeper understanding. By focussing on other soft skills and harder more technical skills, future research could uncover the extent to which implementation intentions could support transfer from a variety of HRD interventions.

Finally, transfer of training has largely been studied by quantitative methods (Brown, McCracken, and O’kane Citation2011; Yang et al. Citation2020). This study aimed to broaden the use and acceptance of qualitative data when studying transfer of training and build on the small number of previous studies such as Brown, McCracken, and O’kane (Citation2011); Johnson, Blackman, and Buick (Citation2018); Lancaster, Di Milia, and Cameron (Citation2013). This qualitative study proved pivotal in uncovering reasons why immediate reflection on the situational cue did not take place and unearthed the possibility that supported reflection could work in conjunction with the implementation intention. More qualitative research should therefore be pursued to continue this ability to unearth hidden possibilities.

Conclusion

This study introduced an underexplored post-training transfer intervention which enabled 67% of the sample population to transfer training to their job role. This is a higher rate of transfer than has been recorded in previous studies considering transfer alone or transfer with post-training interventions. Whilst more research is required, it provides encouraging results for organizations who want to create performance improvement through HRD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Achtziger, A., P. M. Gollwitzer, and P. Sheeran. 2008. “Implementation Intentions and Shielding Goal Striving from Unwanted Thoughts and Feelings.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 34 (3): 381–393. doi:10.1177/0146167207311201.

- Ajzen, I. 2002. “Residual Effects of Past on Later Behaviour: Habituation and Reasoned Action Perspectives.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 6 (2): 107–122. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0602_02.

- Ali, S., M. Tufail, and S. Kiran. 2022. “Trainee’s Motivation to Transfer Has Moderating Effect on the Relationship of Trainees Learning and Trainee’s Behaviour in Social Enterprises of Pakistan.” Global Regional Review VII (II): 164–176. doi:10.31703/grr.2022(VII-II).16.

- Anderson, V. 2017. “Criteria for Evaluating Qualitative Research.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 28 (2): 125–133. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21282.

- Baldwin, T. T., and J. K. Ford. 1988. “Transfer of Training: A Review and Directions for Future Research.” Personnel Psychology 41 (1): 63–105. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1988.tb00632.x.

- Banerjee, P., R. Gupta, and R. Bates. 2016. “Influence of Organisational Learning Culture on Knowledge Worker’s Motivation to Transfer Training: Testing Moderating Effects of Learning Climate.” Current Psychology 36 (3): 606. doi:10.1007/s12144-016-9449-8.

- Bazeley, P., and K. Jackson. 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Bell, B. S., S. I. Tannenbaum, K. J. Ford, R. A. Noe, and K. Kraiger. 2017. “100 Years of Training and Development Research: What We Know and Where We Should Go.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 102 (3): 305–323. doi:10.1037/apl0000142.

- Bhatti, M. A., M. Battour, V. Pandiyan Kaliani Sundram, and A. Aini Othman. 2013. “Transfer of Training: Does It Truly Happen? An Examination of Support, Instrumentality, Retention and Learner Readiness on the Transfer Motivation and Transfer of Training.” European Journal of Training and Development 37 (3): 273–297. doi:10.1108/03090591311312741.

- Bipp, T., and P. A. M. Kleingeld. 2011. “Goal Setting in Practice: The Effects of Personality and Perceptions of the Goal-Setting Process on Job Satisfaction and Goal Commitment.” Personnel Review 40 (3): 306–323. doi:10.1108/00483481111118630.

- Brandstätter, V., A. Lengfelder, and P. M. Gollwitzer. 2001. “Implementation Intentions and Efficient Action Initiation.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 81 (5): 946–960. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.5.946.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Brinkerhoff, R. O., and M. U. Montesino. 1995. “Partnerships for Training Transfer: Lessons from a Corporate Study.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 6 (3): 263–274. doi:10.1002/hrdq.3920060305.

- Brooks, J., S. McCluskey, E. Turley, and N. King. 2015. “The Utility of Template Analysis in Qualitative Psychology Research.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 12 (2): 202–222. doi:10.1080/14780887.2014.955224.

- Brown, T. C. 2005. “Effectiveness of Distal and Proximal Goals as Transfer-Of-Training Interventions: A Field Experiment.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 16 (3): 369–387. doi:10.1002/hrdq.1144.

- Brown, T. C., and M. McCracken. 2010. “Which Goals Should Participants Set to Enhance the Transfer of Learning from Management Development Programmes?” Journal of General Management 35 (4): 27–44. doi:10.1177/030630701003500402.

- Brown, T. C., M. McCracken, and T.L. Hillier. 2013. “Using Evidence-Based Practices to Enhance Transfer of Training: Assessing the Effectiveness of Goal Setting and Behavioural Observation Scales.” Human Resource Development International 16 (4): 374–389. doi:10.1080/13678868.2013.812291.

- Brown, T., M. McCracken, and P. O’kane. 2011. “‘Don’t Forget to Write’: How Reflective Learning Journals Can Help to Facilitate, Assess and Evaluate Training Transfer.” Human Resource Development International 14 (4): 465–481. doi:10.1080/13678868.2011.601595.

- Brown, T. C., A. M. Warren, and V. Khattar. 2016. “The Effects of Different Behavioral Goals on Transfer from a Management Development Program: BEHAVIORAL GOALS and TRANSFER.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 27 (3): 349–372. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21257.

- Bueno, O., J. Busch, and S. A. Shalkowski. 2015. “The No-Category Ontology.” The Monist 98 (3): 233–245. doi:10.1093/monist/onv014.

- Burke, L. A. 1997. “Improving Positive Transfer: A Test of Relapse Prevention Training on Transfer Outcomes.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 8 (2): 115–128. doi:10.1002/hrdq.3920080204.

- Burke, L. A., and T. T. Baldwin. 1999. “Workforce Training Transfer: A Study of the Effect of Relapse Prevention Training and Transfer Climate.” Human Resource Management 38 (3): 227–241. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-050X(199923)38:3<227:AID-HRM5>3.0.CO;2-M.

- Burke, L. A., and H. M. Hutchins. 2007. “Training Transfer: An Integrative Literature Review.” Human Resource Development Review 6 (3): 263–296. doi:10.1177/1534484307303035.

- Button, S. B., J. E. Mathieu, and D. M. Zajac. 1996. “Goal Orientation in Organizational Research: A Conceptual and Empirical Foundation.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 67 (1): 26–48. doi:10.1006/obhd.1996.0063.

- Chauhan, R., P. Ghosh, A. Rai, and D. Shukla. 2016. “The Impact of Support at the Workplace on Transfer of Training: A Study of an Indian Manufacturing Unit: Impact of Support at Work on Training Transfer.” International Journal of Training and Development 20 (3): 200–213. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12083.

- Cheng, E. W. L., and D. C. K. Ho. 2001. “A Review of Transfer of Training Studies in the Past Decade.” Personnel Review 30 (1): 102–118. doi:10.1108/00483480110380163.

- Chiaburu, D. S., and D. R. Lindsay. 2008. “Can Do or Will Do: The Importance of Self-Efficacy and Instrumentality for Training Transfer.” Human Resource Development International 11 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1080/13678860801933004.

- Chiaburu, D. S., and A. G. Tekleab. 2005. “Individual and Contextual Influences on Multiple Dimensions of Training Effectiveness.” Journal of European Industrial Training 29 (8): 604–626. doi:10.1108/03090590510627085.

- Chung, Y., S. M. Gully, and K. J. Lovelace. 2017. “Predicting Readiness for Diversity Training: The Influence of Perceived Ethnic Discrimination and Dyadic Dissimilarity.” Journal of Personnel Psychology 16 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1027/1866-5888/a000170.

- CIPD. 2021. Management Development [factsheet]. England: CIPD.

- Clarke, N. 2002. “Job/Work Environment Factors Influencing Training Transfer Within a Human Service Agency: Some Indicative Support for Baldwin and Ford’s Transfer Climate Construct.” International Journal of Training and Development 6 (3): 146–162. doi:10.1111/1468-2419.00156.

- Cornerstone. 2020. 2020 Cornerstone Performance Management Survey. https://go.cornerstoneondemand.com/rs/076-PDR-714/images/CSOD-2020-Performance-Management-Survey-Whitepaper-USA.pdf

- Curado, C., P. Lopes Henriques, and S. Ribeiro. 2015. “Voluntary or Mandatory Enrolment in Training and the Motivation to Transfer Training.” International Journal of Training and Development 19 (2): 98–109. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12050.

- Diamantidis, A. D., and P. D. Chatzoglou. 2014. “Employee Post-Training Behaviour and Performance: Evaluating the Results of the Training Process: Employee Post-Training Behaviour and Performance.” International Journal of Training and Development 18 (3): 149–170. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12034.

- DiCicco-Bloom, B., and B. F. Crabtree. 2006. “The Qualitative Research Interview.” Medical Education 40 (4): 314–321. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x.

- Facteau, J. D., G. H. Dobbins, J. E. A. Russell, R. T. Ladd, and J. D. Kudisch. 1995. “The Influence of General Perceptions of the Training Environment on Pretraining Motivation and Perceived Training Transfer.” Journal of Management 21 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1177/014920639502100101.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative inquiry 12 (2): 219–245. doi:10.1177/1077800405284363.

- Friedman, S., and S. Ronen. 2015. “The Effect of Implementation Intentions on Transfer of Training: Effect of Implementation Intentions on Training Transfer.” European Journal of Social Psychology 45 (4): 409–416. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2114.

- Gaudine, A. P., and A. M. Saks. 2004. “A Longitudinal Quasi-Experiment on the Effects of Post Training Transfer Interventions.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 15 (1): 57–76. doi:10.1002/hrdq.1087.

- Gegenfurtner, A. 2020. “Testing the Gender Similarities Hypothesis: Differences in Subjective Task Value and Motivation to Transfer Training.” Human Resource Development International 23 (3): 309–320. doi:10.1080/13678868.2018.1449547.

- Gegenfurtner, A., and L. Testers. 2022. “Transfer of Training Among Non-Traditional Students in Higher Education: Testing the Theory of Planned Behavior.” Frontiers in Education (Lausanne) 7.

- Gollwitzer, P. M., and V. Brandstätter. 1997. “Implementation Intentions and Effective Goal Pursuit.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 73 (1): 186–199. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.1.186.

- Gray, D. E. 2007. “Facilitating Management Learning: Developing Critical Reflection Through Reflective Tools.” Management Learning 38 (5): 495–517. doi:10.1177/1350507607083204.

- Greenan, P. 2016. “Personal Development Plans: Insights from a Case Based Approach.” Journal of Workplace Learning 28 (5): 322–334. doi:10.1108/JWL-09-2015-0068.

- Greenan, P., M. Reynolds, and P. Turner. 2017. “Training Transfer: The Case for ‘Implementation Intentions’.” International Journal of Human Resource Development Policy, Practice and Research 2 (2): 49–56. doi:10.22324/ijhrdppr.2.115.

- Griggs, V., R. Holden, A. Lawless, and J. Rae. 2018. “From Reflective Learning to Reflective Practice: Assessing Transfer.” Studies in Higher Education (Dorchester-on-Thames) 43 (7): 1172–1183. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1232382.

- Grossman, R., and E. Salas. 2011. “The Transfer of Training: What Really Matters.” International Journal of Training and Development 15 (2): 103–120. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2419.2011.00373.x.

- Gubbins, C., B. Harney, L. van der Werff, and D. M. Rousseau. 2018. “Enhancing the Trustworthiness and Credibility of Human Resource Development: Evidence-based Management to the Rescue?” Human Resource Development Quarterly 29 (3): 193–202. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21313.

- Hart, S. L., B. Steinheider, and V. E. Hoffmeister. 2019. “Team-based Learning and Training Transfer: A Case Study of Training for the Implementation of Enterprise Resources Planning Software.” International Journal of Training and Development 23 (2): 135–152. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12150.

- Hirudayaraj, M., and J. Matić. 2021. “Leveraging Human Resource Development Practice to Enhance Organizational Creativity: A Multilevel Conceptual Model.” Human Resource Development Review 20 (2): 172–206. doi:10.1177/1534484321992476.

- Holland, R. W., H. Aarts, and D. Langendam. 2006. “Breaking and Creating Habits on the Working Floor: A Field-Experiment on the Power of Implementation Intentions.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 42 (6): 776–783. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2005.11.006.

- Hollenbeck, J. R., and H. J. Klein. 1987. “Goal Commitment and the Goal-Setting Process: Problems, Prospects, and Proposals for Future Research.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 72 (2): 212–220. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.72.2.212.

- Huang, J. L., B. D. Blume, J. Kevin Ford, and T. T. Baldwin. 2015. “A Tale of Two Transfers: Disentangling Maximum and Typical Transfer and Their Respective Predictors.” Journal of Business and Psychology 30 (4): 709–732. doi:10.1007/s10869-014-9394-1.

- Hughes, A. M., S. Zajac, A. L. Woods, and E. Salas. 2020. “The Role of Work Environment in Training Sustainment: A Meta-Analysis.” Human Factors 62 (1): 166–183. doi:10.1177/0018720819845988.

- Ilies, R., and T. A. Judge. 2005. “Goal Regulation Across Time: The Effects of Feedback and Affect.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (3): 453–467. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.453.

- Islam, T., and I. Ahmed. 2018. “Mechanism Between Perceived Organizational Support and Transfer of Training: Explanatory Role of Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction.” Management Research Review 41 (3): 296–313. doi:10.1108/MRR-02-2017-0052.

- Johnson, S. J., D. A. Blackman, and F. Buick. 2018. “The 70: 20: 10 Framework and the Transfer of Learning.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 29 (4): 383–402. doi:10.1002/hrdq.21330.

- Keith, N., and M. Frese. 2008. “Effectiveness of Error Management Training: A Meta-Analysis.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 93 (1): 59–69. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.59.

- Keith, N., T. Richter, and J. Naumann. 2010. “Active/Exploratory Training Promotes Transfer Even in Learners with Low Motivation and Cognitive Ability.” Applied Psychology 59 (1): 97–123. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00417.x.

- Kelly, P. J., J. Leung, F. P. Deane, and G. C. B. Lyons. 2016. “Predicting Client Attendance at Further Treatment Following Drug and Alcohol Detoxification: Theory of Planned Behaviour and Implementation Intentions.” Drug and Alcohol Review 35 (6): 678–685. doi:10.1111/dar.12332.

- Kim, E.J., S. Park, and H.S.(. Kang. 2019. “Support, Training Readiness and Learning Motivation in Determining Intention to Transfer.” European Journal of Training and Development 43 (3/4): 306–321. doi:10.1108/EJTD-08-2018-0075.

- Laker, D. R., and J. L. Powell. 2011. “The Differences Between Hard and Soft Skills and Their Relative Impact on Training Transfer.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 22 (1): 111–122. doi:10.1002/hrdq.20063.

- Lancaster, S., L. Di Milia, and R. Cameron. 2013. “Supervisor Behaviours That Facilitate Training Transfer.” Journal of Workplace Learning 25 (1): 6–22. doi:10.1108/13665621311288458.

- Lawrence, J., and U. Tar. 2013. “The Use of Grounded Theory Technique as a Practical Tool for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis.” Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 11 (1): 29.

- Li, B. 2022. “Thinking Differently with Data in Human Resource Development.” Human Resource Development Review (in press) 22 (1): 15–35. doi:10.1177/15344843221135670.

- Li, A., and A. B. Butler. 2004. “The Effects of Participation in Goal Setting and Goal Rationales on Goal Commitment: An Exploration of Justice Mediators.” Journal of Business and Psychology 19 (1): 37–51.

- Lim, D. H., and S. D. Johnson. 2002. “Trainee Perceptions of Factors That Influence Learning Transfer.” International Journal of Training and Development 6 (1): 36–48. doi:10.1111/1468-2419.00148.

- Locke, E. A., and G. P. Latham. 2006. “New Directions in Goal-Setting Theory.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 15 (5): 265–268. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00449.x.

- London, M., E. M. Mone, and J. C. Scott. 2004. “Performance Management and Assessment: Methods for Improved Rater Accuracy and Employee Goal Setting.” Human Resource Management 43 (4): 319–336. doi:10.1002/hrm.20027.

- Lowe, E. J. 1998. The Possibility of Metaphysics: Substance, Identity, and Time. New York, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Maley, J. 2014. “Sustainability: The Missing Element in Performance Management.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration 6 (3): 190–205. doi:10.1108/APJBA-03-2014-0040.

- Martin, H. J. 2010. “Workplace Climate and Peer Support as Determinants of Training Transfer.” Human Resource Development Quarterly 21 (1): 87–104. doi:10.1002/hrdq.20038.

- McDowall, A., and M. N. K. Saunders. 2010. “UK Managers’ Conceptions of Employee Training and Development.” Journal of European Industrial Training 34 (7): 609–630. doi:10.1108/03090591011070752.

- Murthy, N. N., G. N. Challagalla, L. H. Vincent, and T. A. Shervani. 2008. “The Impact of Simulation Training on Call Center Agent Performance: A Field-Based Investigation.” Management science 54 (2): 384–399. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1070.0818.

- Na-Nan, K., and E. Sanamthong. 2020. “Self-Efficacy and Employee Job Performance: Mediating Effects of Perceived Workplace Support, Motivation to Transfer and Transfer of Training.” International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 37 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1108/IJQRM-01-2019-0013.

- Narayan, A., and D. Steele-Johnson. 2007. “Relationships Between Prior Experience of Training, Gender, Goal Orientation and Training Attitudes.” International Journal of Training and Development 11 (3): 166–180. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2419.2007.00279.x.

- Nesbit, P. L. 2012. “The Role of Self-Reflection, Emotional Management of Feedback, and Self-Regulation Processes in Self-Directed Leadership Development.” Human Resource Development Review 11 (2): 203–226. doi:10.1177/1534484312439196.

- Nijman, D.J. -J.M., W. J. Nijhof, A. A. M. (. Wognum, and B. P. Veldkamp. 2006. “Exploring Differential Effects of Supervisor Support on Transfer of Training.” Journal of European Industrial Training 30 (7): 529–549. doi:10.1108/03090590610704394.

- Nikandrou, I., V. Brinia, and E. Bereri. 2009. “Trainee Perceptions of Training Transfer: An Empirical Analysis.” Journal of European Industrial Training 33 (3): 255–270. doi:10.1108/03090590910950604.

- Norman, P., T. L. Webb, and A. Millings. 2019. “Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Implementation Intentions to Reduce Binge Drinking in New University Students.” Psychology & Health 34 (4): 478–496. doi:10.1080/08870446.2018.1544369.

- Nowell, L. S., J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1177/1609406917733847.

- Orbell, S., and P. Sheeran. 2000. “Motivational and Volitional Processes in Action Initiation: A Field Study of the Role of Implementation Intentions.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 30 (4): 780–797. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02823.x.

- O’reilly, M., and N. Parker. 2013. “‘Unsatisfactory Saturation’: A Critical Exploration of the Notion of Saturated Sample Sizes in Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Research 13 (2): 190–197. doi:10.1177/1468794112446106.

- Palagolla, N. 2016. “Exploring the Linkage Between Philosophical Assumptions and Methodological Adaptations in HRM Research.” Journal of Strategic Human Resource Management 5 (1). doi:10.21863/jshrm/2016.5.1.020.

- Pulakos, E. D., R. M. Mueller Hanson, S. Arad, and N. Moye. 2015. “Performance Management Can Be Fixed: An On-The-Job Experiential Learning Approach for Complex Behavior Change.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 8 (1): 51–76. doi:10.1017/iop.2014.2.

- Quinones, M. A. 1995. “Pretraining Context Effects: Training Assignment as Feedback.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 80 (2): 226–238. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.80.2.226.

- Rahyuda, A., J. Syed, and E. Soltani. 2014. “The Role of Relapse Prevention and Goal Setting in Training Transfer Enhancement.” Human Resource Development Review 13 (4): 413–436. doi:10.1177/1534484314533337.

- Ran, S., and J. L. Huang. 2019. “Enhancing Adaptive Transfer of Cross-Cultural Training: Lessons Learned from the Broader Training Literature.” Human Resource Management Review 29 (2): 239–252. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.08.004.

- Rekalde, I., J. Landeta, and E. Albizu. 2015. “Determining Factors in the Effectiveness of Executive Coaching as a Management Development Tool.” Management Decision 53 (8): 1677–1697. doi:10.1108/MD-12-2014-0666.

- Renta, D., A. Inés, J. Miguel Jiménez-González, M. Fandos-Garrido, and Á. Pío González-Soto. 2014. “Transfer of Learning: Motivation, Training Design and Learning-Conducive Work Effects.” European Journal of Training and Development 38 (8): 728–744. doi:10.1108/EJTD-03-2014-0026.

- Robson, F., and S. Mavin. 2014. “Evaluating Training and Development in UK Universities: Staff Perceptions.” European Journal of Training and Development 38 (6): 553–569. doi:10.1108/EJTD-04-2013-0039.

- Rubin, E. V., and A. Edwards. 2020. “The Performance of Performance Appraisal Systems: Understanding the Linkage Between Appraisal Structure and Appraisal Discrimination Complaints.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 31 (15): 1938–1957. doi:10.1080/09585192.2018.1424015.

- Sahoo, M., and S. Mishra. 2019. “Effects of Trainee Characteristics, Training Attitudes and Training Need Analysis on Motivation to Transfer Training.” Management Research Review 42 (2): 215–238. doi:10.1108/MRR-02-2018-0089.

- Saks, A. M., and M. Belcourt. 2006. “An Investigation of Training Activities and Transfer of Training in Organizations.” Human Resource Management 45 (4): 629–648. doi:10.1002/hrm.20135.

- Schiele, H., and S. Krummaker. 2011. “Consortium Benchmarking: Collaborative Academic–Practitioner Case Study Research.” Journal of Business Research 64 (10): 1137–1145. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.11.007.

- Seawright, J., and J. Gerring. 2008. “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options.” Political Research Quarterly 61 (2): 294–308.

- Seijts, G. H., and G. P. Latham. 2001. “The Effect of Distal Learning, Outcome, and Proximal Goals on a Moderately Complex Task.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 22 (3): 291–307. doi:10.1002/job.70.

- Seijts, G. H., and G. P. Latham. 2012. “Knowing When to Set Learning versus Performance Goals.” Organizational Dynamics 41 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.orgdyn.2011.12.001.

- Sheeran, P., and S. Orbell. 1999. “Implementation Intentions and Repeated Behaviour: Augmenting the Predictive Validity of the Theory of Planned Behaviour.” European Journal of Social Psychology 29 (2–3): 349–369. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199903/05)29:2/3<349:AID-EJSP931>3.0.CO;2-Y.

- Sheeran, P., T. L. Webb, and P. M. Gollwitzer. 2005. “The Interplay Between Goal Intentions and Implementation Intentions.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 31 (1): 87–98. doi:10.1177/0146167204271308.

- Soderhjelm, T. M., T. Nordling, C. Sandahl, G. Larsson, and K. Palm. [2020] 2021. “Transfer and Maintenance of Knowledge from Leadership Development.” Journal of Workplace Learning 33 (4): 273–286. doi:10.1108/JWL-05-2020-0079.

- Tannenbaum, S. I., and G. Yukl. 1992. “Training and Development in Work Organizations.” Annual Review of Psychology 43 (1): 399–441. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.43.020192.002151.

- Taylor, P. J., D. F. Russ-Eft, and D. W. L. Chan. 2005. “A Meta-Analytic Review of Behavior Modeling Training.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (4): 692–709. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.692.