ABSTRACT

This article analyses the conditions for the development of caravan tourism in Western Australia. It describes caravan tourism within tourism in general, presents its development in Australia, and investigates the relationship between the distribution of tourism assets and the location of campsites. The article analyses the data on the distribution of natural and anthropogenic values and campsite bases. The point bonitation method was used, the most and least attractive areas of the state were indicated and, using the Pearson correlation ratio, it was shown that there is a significant relationship between the attractiveness of tourist areas and the distribution of camping fields in Western Australia.

Introduction

Caravan tourism is one type of tourism, combining both leisure and sightseeing aspirations and the experience of freedom (Kearns et al., Citation2017). According to Rice et al. (Citation2019) camping is an emerging tourism sector. However, it is rarely the subject of scientific research (Rice et al., Citation2019; Triantafillidou & Siomkos, Citation2013). Caldicott et al. (Citation2014) show that the phenomenon of this type of tourism is connected with lifestyle choices and the visibility of freedom camping. Moreover, camping is a common recreational activity in natural protected areas (Dixon, Citation2017). However, it is possible for it to be developed in such a way as to reduce human impact on the environment (Marion et al., Citation2016). Brooker and Joppe carried out a review of camping research and suggested a direction for future studies (Citation2014). The lifestyle possibilities connected with camping activities and their motivations were explained by Sirakaya and Woodside (Citation2005) and the satisfaction tourists derived from camping by Dunn Ross and Iso-Ahola (Citation1991) and Yoon and Uysal (Citation2005).

According to the definition formed by Prideaux and McClymont (Citation2006), caravanning is a subset of tourism where the main form of accommodation used during a trip is a camping vehicle. Simeoni and Cassia (Citation2019) have shown that recreational vehicle manufacturers play an active role in the co-creation of tourism experiences. The motivations for drive tourism were examined by Hardy and Gretzel (Citation2011). Australia is a leader in caravan tourism and is a place where this specific type of leisure activity is very popular. The number of caravan journeys undertaken in Australia exceeds 12 million annually (Caravan Industry Association of Australia, Citation2018). Even the experience of Chinese tourists, who use their recreational vehicles when travelling in Australia, was recently analysed (Wu & Pearce, Citation2014). Innovation typology for the Australian outdoor hospitality parks sector was shown by Brooker et al. (Citation2012). This country is also famous for its winery landscapes (Myga-Piątek & Rahmonov, Citation2018). In Australia camping was promoted as a healthy recreation (Metusela & Waitt, Citation2012). Western Australia was selected for analysis, as it remains one of the lesser-known areas of Australia. Due to its unique natural environment and the presence of numerous anthropogenic values resulting from thousands of years of Aboriginal culture and from its colonial past, the area is one of the more attractive parts of the Australian continent. The significant geographical location of tourist attractions in Western Australia makes caravanning one of the most convenient ways to travel around the state. The aim of this article is to indicate the most attractive features of caravan tourism areas in Western Australia and to obtain an answer to the question: Is there a connection between tourist attractions and camping base locations in Western Australia? Three additional questions were also considered:

Are the largest number of campsites located in the areas that hold the highest level of attractiveness for tourists?

Is the location of a camping base determined more by natural values or by anthropogenic values?

Which of the natural values has the greatest impact on the distribution of the camping base?

The main aim of the study was to explain the spatial distribution of the camping base in Australia and whether the campsites are located closer to the more attractive areas.

The article presents the following research hypotheses: In Western Australia there is a high correlation between the attractiveness of tourist areas and the location of campsites. The largest number of campsites are to be found in the most attractive tourist areas in Western Australia. The distribution of the camping base in Western Australia is determined to a greater extent by natural values than by anthropogenic values. Among the natural values, climatic conditions and distance from the shoreline have the greatest impact on the distribution of the campsite base in Western Australia. The assessment of the tourism attractiveness of the state was based on the division of the region into a network of 300 basic fields. The time range studied is the second decade of the twenty-first century. The analysis uses the latest available data, from 2018, on the distribution and size of the camping base, as well as data on tourist attractions from the second decade of the twenty-first century. Although the point bonitation method is sometimes criticized for being prone to subjectivity, due to the lack of a uniform system for selecting assessment criteria, the freedom to set a scale of values and the difficulty in comparing several authors’ results (Jakiel, Citation2015; Parzych, Citation2013). The following are usually analysed when using the point bonitation method for the assessment of natural tourism attractiveness: the forest cover, access to the coastline, the presence of national parks and other nature reserves, climate conditions and differentiation of landforms (Kowalczyk, Citation2000; Piraszewska, Citation2004; Tertelis, Citation2012).

To analyse the strength of the relationship between tourism values and the location of the camping base in Western Australia the Pearson correlation coefficient was used (Norcliffe, Citation1986).

The concept of caravan tourism

The biggest growth in caravan tourism in Australia took place after World War II. In 2018 the number of foreign arrivals to Australia was 9.24 million, which was an increase of 4.8% compared to 2017. From 2014 to 2018 the number of foreign arrivals was stable increasing by 33.5% (www.unwto.org). The first important concept used in this article is caravanning (caravan tourism). This concept is understood in the Australian context, where caravanning tourism is defined as the practice of spending free time in a camping vehicle (Brooker, Citation2011). Many research papers have considered the development of American and Australian caravan tourism (Brooker & Joppe, Citation2014).

According to Brooker and Joppe (Citation2014) ‘camping is a form of accommodation as well as a more holistic activity’. According to Caldicott et al. (Citation2014) a recreational vehicle (RV) is defined as ‘any motorized or towable caravan used as a mode of accommodation’. Moreover, the term ‘caravan’, interchangeable with RV, includes pop-tops, campervans, camper-trailers, tent-trailers, motorhomes, slide-ons and fifth wheelers.

Among the most important concepts used in the article are the descriptions of tourism attractiveness and tourism values. A tourist attraction is the occurrence of a certain characteristic that attracts tourists to certain areas thanks to the natural landscape, climate, historical monuments, as well as various interesting spatial development objects (Kowalczyk, Citation2000). On the other hand, tourism assets are ‘all elements of the natural and non-natural environment that are of interest to tourists and determine the tourism attractiveness of a given place, town, area’ (Kowalczyk, Citation2000, p. 88). There are natural values, meaning ‘a set of elements of natural origin’ and non-natural values (anthropogenic, cultural) constituting ‘products of human activity’ (Gołembski, Citation2002, p. 66). The notion of tourism values is related to the concept of communication accessibility by means of transport to the destination for the journey undertaken (Kowalczyk, Citation2000; as cited in Warszyńska & Jackowski, Citation1978).

Active tourism requires participants to be in a specific psychophysical condition but the participants’ ability to use specialized tourist equipment is not so important. However, natural values, communing with the natural environment and open space are key (Mokras-Grabowska, Citation2015, Tomik Citation2015). One of the forms of active tourism is drive tourism (car and motorbike). According to the definition proposed by Prideaux and Carson (Citation2011), the term drive tourism is used to describe travel by any form of mechanically powered, passenger-carrying road transport, with the exclusion of coaches and bicycles. A somewhat more detailed approach is presented by Hardy (Citation2006) in her paper, Drive tourism: A methodological discussion with a view to further understanding the drive tourism market in British Columbia, Canada (Citation2006), who describes drive tourism as a type of tourism where people take leisure trips in their own or hired vehicles. It is a type of tourism in which the vehicle is used as the basic form of transport, and tents, campsites, hotels, guest houses or other accommodation facilities constitute a basic place of accommodation. In addition to the traditional division of motor tourism into two main types of car and motorcycle tourism, more detailed divisions can be distinguished within it. Prideaux and Carson (Citation2011) write about a wide range of road-based travel including day trips and overnight travel in a family car or a rental car, travel in four-wheel-drive vehicles (4WD), caravanning, travel in recreational vehicles (RVs) and motorhomes, and touring by motorcycle.

Although motor tourism is an important component of the tourism industry, researchers do not show much interest in undertaking research on the role of the car in shaping tourism demand and increasing the availability of tourism resources which, as noted by Prideaux and Carson (Citation2011), is surprising. Even 80 years ago, the idea of spontaneously spending free time using your own vehicle was unattainable for most people (Hardy, Citation2006). According to Prideaux (Citation2002) the main elements of motor tourism are: the road network and all activities related to its development and maintenance; and accommodation, including hotels, motels and guest houses.

Caravan tourism as a form of active tourism

A special form of motor tourism is caravan tourism (often referred to as recreational vehicle (RV) tourism in English literature). It is characterized by the fact that the food and accommodation basis for tourists is their own tent, caravan or motorhome. The campsite base is an integral part of caravan tourism and is the basic resting place where a participant of caravan tourism is hosted. A well-developed camping infrastructure creates favourable conditions for the development of caravan tourism; hence, in the literature on the subject, caravan tourism is often discussed together with the issue of camping tourism, referred to as a subgenus of caravan tourism (Caldicott & Scherrer, Citation2013; Prideaux & McClymont, Citation2006; Sala, Citation2015).

Caravan tourism is also associated with the need to master the ability to use tourist equipment (undoubtedly a camping vehicle) and various camping techniques (Łobożewicz & Bieńczyk, Citation2001). In addition to the knowledge of traffic rules and regulations, those travelling by car with a caravan or motorhome must demonstrate their ability to drive in conditions other than the environment in which they usually move. As noted by Prideaux and Carson (Citation2011), the most obvious example here may be a situation in which drivers should adjust to the right- or left-hand side of the road in the case of foreign trips. In addition to the vehicle, the basic equipment for all those who undertake caravan tourism is also a tent, sleeping equipment, and household equipment, enabling the preparation of meals (Merski & Warecka, Citation2009).

In research in the field of motor tourism Trimble (Citation1999) shows that there is a clear desire among tourists to undertake this kind of trip, because it fulfils needs that cannot be met by other forms of tourism (Olsen, Citation2002). Travelling by car gives the tourist the opportunity to freely choose a place and date of travel and to visit areas outside the main tourist routes (Łobożewicz & Bieńczyk, Citation2001). The above separation from the tourism mainstream is manifest in the kind of activities undertaken by motorized tourists who are focused on having ‘real experiences’, combining both active and passive forms of spending their free time. This view is shared by Darley et al. (Citation2017), who write about the ‘pursuit of freedom’ as one of the main motivating factors for travelling in a camping vehicle.

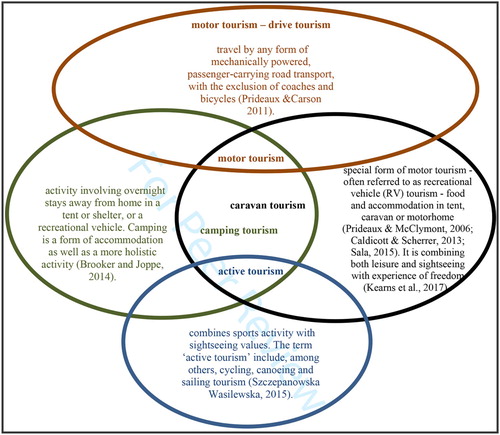

The social aspect of caravan tourism is also important. The specific attraction of the campsite and the possibility of spending free time with family and friends in an attractive location are indicated as the main motives for participation in caravan tourism and camping (American Camper Report, Citation2017). As McClymont et al. (Citation2011) note, the experience of caravanning combined with staying in the characteristic, community atmosphere of camping fields, provides a wide range of opportunities to meet, socialize and develop friendships, which is rare in other forms of tourism. Caravanning is considered a means of travelling for people who have common ties and interests. It is therefore common for tourists undertaking caravan tourism to see themselves not as individual travellers, but as part of a community (Patterson et al., Citation2015). Caravanning meets the requirements of modern, active recreation, being in direct contact with the natural environment and, at the same time, providing the opportunity to move around. The main definitions used in the article were presented by .

Figure 1. The definitions used in the article. Source: authors’ own elaboration on the basis: (Brooker & Joppe, Citation2014; Caldicott & Scherrer, Citation2013; Kearns et al., Citation2017; Prideaux & Carson, Citation2011; Prideaux & McClymont, Citation2006; Sala, Citation2015; Szczepanowska & Wasilewska, Citation2015).

The development of caravan tourism in Australia

Caravan tourism is one of the directions of tourism development which has an established position in some highly developed countries – in the United States and western Europe. The attractiveness of this tourism segment is particularly evident in Australia, where travelling with a caravan or camper has become one of the most common ways of rest. Despite the huge popularity of caravan tourism in Australia, it does not arouse much interest among authors; hence the subject literature in this area is quite limited. As emphasized by Prideaux and McClymont (Citation2006), it is surprising that so little research has been done to better understand it considering the size of the caravan industry in Australia. Caravanning is one of the oldest forms of travel known to man and existed long before the invention of a mechanical engine. The beginnings of the development of caravans go back to the era, in which the main pulling forces were horses. In the second half of the nineteenth century, merchants and hawkers used caravans to travel by land along trade routes. The term ‘caravan’ then referred to a convoy of covered carts, travelling in groups to provide greater security (Patterson et al., Citation2015). After World War I, along with the development of motoring, horse-drawn carts were replaced with mechanized vehicles, and the commercial production of caravans and motorhomes began, being gradually equipped with such elements as: running water, toilets, gas cylinders and heating systems. In the 1930s, caravanning became a particularly popular form of recreation in the United States, where the number of camping vehicles produced reached about 400,000 units (Patterson et al., Citation2015). In Australia, the roots of caravan tourism go back to the nineteenth century when the first houses were built on wheels, harnessed to horses or oxen, and were used by settlers, gold seekers and shepherds. The first campers in the form known today began to appear in the 1920s. Between World War I and World War II, caravan tourism in Australia was not well organized – it concerned a small group of enthusiasts, and the production of commercial campers was rare. By the 1950s, the caravan’s design had become widespread. As Beilharz and Supski (Citation2017) wrote in the 1930s, the construction of caravans by individuals was more popular because those produced commercially exceeded the financial capacity of the majority of the population. It was a period when many publications appeared in Australia containing detailed plans and instructions on the construction of caravans.

One of the pioneers of the commercial production of caravans in Australia was RJ Rankin – an entrepreneur from Sydney, who constructed his first motorhome in 1928 (Beilharz & Supski, Citation2017). It was a lightweight trailer that could be towed by a car. Rankin’s camping trailer proved to be a great success; hence, in 1929 commercial production started. By 1934, Rankin’s workshop had a fleet of 25 caravans.

The real rise of caravan tourism and the industry associated with the production of motorhomes in Australia followed World War II. With the post-war development of motoring, ownership of cars became more and more common, and the massification of tourist traffic meant that holiday trips were also within the reach of the working class. The car became a symbol of freedom, giving the impulse for the further development of caravanning, which quickly gained more and more recognition, becoming the main form of leisure for Australians (Caldicott, Citation2011). Due to innovations introduced, the equipment in vehicles changed significantly, differing from the modest, handmade caravans of the 1940s. Their special construction, providing space and equipment for storing food and a separate sanitary part with a toilet, wash basin and shower, made caravans more and more like houses on wheels. An especially important improvement that made caravanning more accessible to many Australians was the folding caravan, patented in 1952 (Beilharz & Supski, Citation2017).

By 1953, there were 60 establishments in Australia involved in the production of motorhomes and caravans. Four companies were particularly intensive – Viscount and Millard in New South Wales, Franklin in Victoria and Chesney in Queensland. In the 1960s, at a time when the caravanning industry in Australia was going through a second wave of prosperity these four accounted for over 80% of total van production in Australia; hence, in the caravanning industry, they were often referred to as the ‘big four’ (Caldicott, Citation2011). The 1970s is the most successful period in the history of the production of camping vehicles in Australia.

The gradual revival of caravan tourism in Australia took place in the mid-1990s. Thanks to the reaction of the caravanning industry to changing consumer preferences and the emergence of more fuel-efficient vehicles, the development of four-wheel drive vehicles, more aerodynamic production, easier to tow trailers, and the improved standard of the national road network that enabled the car to reach the majority of the continent, there was an increase in demand related to caravanning. In 2010, the level of production of caravans and motorhomes had amounted to 23,000 units (Caldicott & Scherrer, Citation2013).

Many categories of camping fields developed in response to the different demands from various social groups in Australia. Despite the lack of an official division of Australian campsites into types you can find many types of campsites in the literature on the subject, distinguished based on the location and purpose of the tourists visiting them (Tourism Research Australia, 2007; Caldicott, Citation2011). The most frequently cited categories include:

transitory parks (transit parks) or night parks (overnight parks) – located next to main roads, and mainly intended for short-term stays;

city parks – located near major population centres, to meet the needs of both short- and long-term tourists;

resort parks – mainly used for long-term tourists and vacationers;

nature parks – located near attractive nature areas.

Many campsites combine different functions, falling into two or more categories. As a result of marketing strategies designed to improve the image of camping fields and attract the attention of a wider audience, there is also a variety of terminology concerning the names of camping fields in the literature. Terms such as ‘outdoor hospitality park’, ‘holiday home park’ or ‘holiday village’ suggest that camping is something more than a low-budget holiday. Modern equipment in camping sites means that during the stay visitors do not have to leave the campsite in order to partake in various forms of activity (Brooker, Citation2011). At the beginning of the twenty-first century, there were over 1,800 campsites in Australia, which were the second largest accommodation base for short-term travel except for motels (Hayllar et al., Citation2006). Camping parks in Australia are usually small companies run by private operators (less often local authorities), varying in size, complexity and the level of services provided.

Most campsites in Australia are located outside large urban centres, being the main form of accommodation in regional areas. Modern campsites offer many attractive facilities, such as refuelling, internet access and car washing; and are located near hiking, cycling and car routes, tennis courts and golf courses (Foley & Hayllar, Citation2007). Despite the large interest in caravan tourism in Australia, the number of campsites has been declining for several years (Caldicott, Citation2011; Prideaux & McClymont, Citation2006). This phenomenon is particularly noticeable in coastal areas where, as a result of developing holiday resorts, camping grounds are gradually being replaced by emerging hotels ().

Table 1. The number of nights spent by caravanning tourists in camping sites and the number of registered motorhomes in Australia in 2011–2017.

Assessment of tourism attractiveness of Western Australia in terms of caravan tourism

As noted by Caravan Industry Association Western Australia, there is no better way to discover the untouched corners of Australia’s largest state than to set out and explore it in its own way (Caravan Industry Association Western Australia, Citation2018 – www.caravanindustry.com.au). From the point of view of caravan tourism, Western Australia is a very interesting area, its potential deriving from both the richness of the natural environment and numerous elements of material culture. Travelling by car, or by car and caravan or tent, is one of the best ways to move off the beaten path and discover the true beauty of the state, and favourable climatic conditions make it a convenient place to relax throughout the year. Western Australia is the largest state of Australia, located in the western part of the continent close to the Indian Ocean. Due to its large area and considerable distances, the region is predisposed primarily for tourists using their own means of transport – motorized tourism (including caravan tourism). Choosing this kind of tourism is also due to the landscape of Western Australia, which is not very diverse. It is an area of lowland character – the vast majority of its areas are located lower than 450 metres above sea level.

The majority of the state is located in the physico-geographical region of the Western Australian Plateau, which is one of the three main regions of Australia’s physical geography. The Western Australian Plateau is an area of the plain, varied by small mountain ranges. Its north-western part is occupied by the Pilbara region with the Hamersley Mountains, in which the highest peak of Western Australia is located (Mount Meharry with a height of 1,250 metres above sea level). A large part of the highlands is made up of deserts and semi-deserts, stretching over thousands of kilometres, with a hot, dry climate (Great Sandy Desert, Great Victoria Desert, Gibson Desert). The most northern part of Western Australia is the Kimberley Upland. It is under the influence of the summer monsoon; hence, it is considered the most tropical part of the state due to the high rainfall occurring here from December to February. The region is drained by periodic (creeks) and episodic (including Fitzroy, Drysdale, Ord) rivers. Rapid streams contribute to erosion processes, the effect of which are numerous surface forms: gorges, canyons, ravines. The highest elevation of the Kimberley Upland is Mount Ord (936 m above sea level) in the King Leopold mountain range. The south-western part of the state (i.e. Swanland) is of a different nature. The area extending from Geraldton to Esperance has a slightly undulating terrain with a much milder climate. The largest forest areas in Western Australia are close to the only permanent rivers (including the Swan and Blackwood). Perth, the capital of Western Australia, is also in this area. The southern end of the state is occupied by the Nullarbor Lowland, in an area where intensive karst processes operate. Numerous forms of underground karst can be observed in caves located here.

Among the many natural values of Western Australia, protected areas are particularly worth noting. Being the largest of the Australian states, the natural environment is unique and protected in over 1,800 areas (including 128 national parks). There are 252.500 km2 under protection, which is about 10% of the surface area.

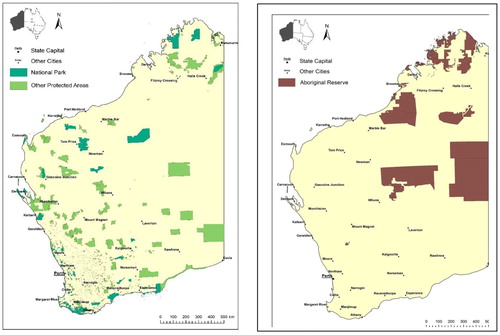

Most protected areas are located in the south-western part of the state (however, they are much smaller in area than protected areas in the north, north-west or central parts). The oldest Western Australian national park is John Forrest, created in 1898, and the occurrence of protected areas is one of the most important factors affecting the number of caravan tourists travelling through Western Australia. They are a convenient place to rest, to go for walks and to get to know the nearby nature spots. Western Australia is one of the most unique environments in the world. About 10,000 plant species are located here, one third of which are endemic (mainly various eucalyptus varieties). An especially attractive time of the year for a trip through Western Australia is spring (Smith, Citation2000). The isolation of the Australian continent from other land areas has also meant that the animal species living here are different than on other continents. Western Australia is home to over 150 species of mammals. Marsupials are common here, the main representative of which is the kangaroo. In the Western Australian national parks, you can also find koalas, wallabies and wombats and various species of squirrels. Bird fauna (the most famous of which are ostrich emus and various species of parrots) and reptiles are also abundant ().

Figure 2. Protected areas and Aboriginal reserves in Western Australia. Source: authors’ own elaboration on the basis of Department of the Environment and Energy (www.environment.gov.au/fed/catalog/main/home.page).

This area of Western Australia is also attractive in terms of anthropogenic values, the wealth of which consists of the legacy of Aboriginal culture and the European colonial past. Aborigines were the first civilization that appeared on the Australian continent. Hunting tools that have been found, traces of fire and rock paintings show that they may have inhabited areas of today’s Australia up to 50,000 years ago. Western Australia is inhabited by approximately 76,000 people of Aboriginal origin, which is a 3% of population of this area). There are seven main groups of tribes (Kalumburu, Djarindjin-Lombadina, Yungngora, Jigalong, Wilun, Papulankutja) (CitationAustralian Government, Indigenous Affairs, www.indigenous.gov.au).

Traces of the Aboriginal cultural heritage in the form of, above all, rock paintings can be found in the areas of Aboriginal reserves. There are 17 isolated areas of Aboriginal life in Western Australia, occupying a total area of over 340,000 km2. It is worth noting that the term ‘reserve’ in Australia has a more conventional meaning. Due to the fact that Aboriginal reserves do not permit any civilizational human activity, they play a similar role with regard to nature as national parks.

The high colonial status of Western Australia is also evidenced by the colonial history of the state dating back to the eighteenth century as is presented in over 160 museums and art galleries. A specific type of tourist attraction in Western Australia, especially popular from the point of view of motorized tourists, are ‘Big Things’ – large installations located on the main roads in Australian towns.

Criteria for assessing the tourism attractiveness of Western Australia

The point bonitation method was used to assess the variability of tourism attractiveness of Western Australia. It is a method that involves assigning the selected features (occurring within the examined spatial units, the so-called basic fields) a specific number of points on the basis of a previously chosen value scale. Despite the fact that the point bonitation method is criticized for its subjectivity due to the lack of a uniform system of selection of evaluation criteria, freedom in determining the scale of values as well as difficulty in comparing the results of research of several authors, it is widely used in tourism geography and other tourism sciences (Jakiel, Citation2015; Parzych, Citation2013). The authors’ analysis of the attractiveness of the area for tourists was based on primary basic fields. The authors covered the studied area with a grid, resulting in 300 basic fields being analysed, each 100 kilometres by 100 kilometres, covering a total area of 10,000 km2. In the case of fields that did not fit entirely within the boundaries of the study area, the assessment covered their entire area. Islands and basic fields where the land area was less than 5% of the total area of the field were excluded from the study. Each of the basic fields was assigned a point value based on the calculations carried out.

All fields were evaluated based on 21 elements describing natural values (11 elements), anthropogenic values (8 elements) and transport accessibility (2 elements). Due to the subject of the work, the elements describing the attractiveness of Western Australia were sought to be selected in a way that would take into account their relevance from the point of view of caravan tourism. As far as the availability of data allowed, the selection of features was based not only on the authors’ own observations, but also on activities identified as being undertaken by caravan tourists. Among the natural values examined were climatic elements (average annual air temperature, annual rainfall); hydrographic elements in the form of surface permanent water reservoirs, forest areas, protected areas (national parks, other protected areas, UNESCO natural sites); geological and geomorphological elements (caves, waterfalls, geological heritage objects); and distance from the shoreline. The assessment of the attractiveness of basic fields in terms of anthropogenic values was carried out on the basis of such elements as: campsites, other camping sites, museums and art galleries, historical facilities, tourist information points,Footnote1 ‘Big Things’ facilities, cultural UNESCO sites and Aboriginal reserves. The third group of elements referred to communication accessibility. It was assessed on the basis of elements of the communication infrastructure including the network of roads and airports. The values and communication accessibility were inventoried mainly on the basis of Australian and world spatial information systems (NationalMap, WorldClim – Global Climate Data, DIVA – GIS – Free Spatial Data) and spatial data provided by websites of Australian governmental institutions.

Each element was assigned the appropriate point scale, on the basis of which a specific number of points was assigned to the individual primary fields. Points elements were assessed depending on their number in a given basic field, while points for surface elements were awarded on the basis of the percentage of space they occupied in the basic field. Assuming that the landscape is the most attractive when there is a contrast of its elements and based on previous works using the bonitation point method (including Czubaszek et al., Citation2016; Dudek, Citation2012; Jakiel, Citation2015). The criterion for the assessment of water reservoirs and forests was the length of the shoreline. In the case of point elements and surface elements, the Jenks method was used to determine the class intervals of the scoring. This method was based on the so-called natural limits of division, giving the best results for data distributed unevenly (Malinowski et al., Citation2009). A different method was used for climatic elements and elements measured by the length, where equal values of intervals were used. It was assumed that the higher the value of the examined feature in a given unit, the greater its attractiveness, hence each subsequent interval differed from the previous by one point. In the absence of an element, the granted point value was zero. The exception to the above assumptions were climatic elements and distance from the shoreline, where no value was given zero. Due to the high subjectivity of the assessment of climatic elements, the highest number of points was decided to allocate to central values, and the smallest extreme values. Also in the case of camping fields, in order to emphasize their exceptional importance as an essential component of anthropogenic potential from the perspective of caravanning tourism, additional points were awarded in the assessment (the value of subsequent intervals differed by two points).Footnote2

On the basis of selected criteria validation maps were made for each of the elements of attractiveness assessment. The assessment of the tourist attractiveness of individual primary fields was obtained by adding in each field the number of points awarded to the items being assessed. The maximum number of points for natural values could amount to 40, for anthropogenic values 31, and for the communication accessibility nine. Depending on the sum of the points obtained, individual fields were assigned to appropriate intervals determining the degree of their attractiveness. As in the case of the assessment of individual elements, the set of final values was determined using the method of natural compartments, dividing them into five classes. The final result of the research is a map presenting the total assessment of the tourist attractiveness of the studied area ().

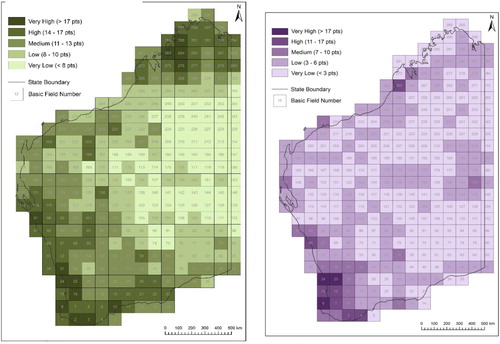

Figure 3. Assessment of the attractiveness of natural (green) and anthropogenic (purple) features of Western Australia. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

The map showing the valorization of elements of the natural environment presents the diverse attractiveness of Western Australia in terms of natural values. On the basis of the results obtained, two main areas of the state are distinguished by the highest mark. The first of these is part of the state of the Kimberley Upland, located in the northern part. This area had very high or high attractiveness, and makes up about 36% of the administrative area of Kimberley and 7% of the area under study. The overall high attractiveness of the area is due to the fact that it is one of the least transformed parts of Australia. Despite unfavourable climatic conditions (average annual temperature reaches 30 ⁰C; annual rainfall is over 900 mm), the wild and natural aspects of the area captivate tourists. Significant parts of the area are protected – there are ten national parks and over 30 nature reserves with unique natural values and landscapes. One of the most famous – Purnululu National Park – is located here, protecting the unique landscape that resembles the natural sculptures of the high Bungle Bungle range. The area of about 2,400 km2 was shaped as a result of weathering and erosion processes along alternate layers of sandstone and quartzite (Jelonek & Soja, Citation1997). In 2003, the park was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. A 55 km route for motorized tourists has been marked out in the park, and pedestrian routes lead to its most attractive parts (Maik, Citation2003). The other national parks located in this part of the state are Wolfe Creek, Geikie Gorge, Windjana Gorge, Tunnel Creek, Prince Regent, Mitchell River, Drysdale River, Mirima and Lawley River ().

Table 2. Classes of the tourist attractiveness indicator.

The high attractiveness of the northern part of Western Australia is also due to the significant forest cover and high concentration of punctual values. The forests growing in the northern part of the Kimberley Upland are characterized by a varied coastline and the tree species found here is limited to this region (and includes the Australian baobab) (Llewellyn & Mylne, Citation2004). In the area occupying approximately 420,000 km2 there are 96 caves (53 of them in Field 283) and 216 out of 241 waterfalls were identified. A large number of waterfalls is associated with a high annual rainfall in the north-western extremities of the continent, reaching over 900 mm. Many of them, such as the Mitchell, Horizontal or King George waterfalls, are big tourist attractions (CitationTourism Western Australia, www.westernaustralia.com).

The second most attractive area of Western Australia in terms of natural values is much more extensive, stretching about 200 kilometres from the shoreline, a part that covers the territory from the area located about 1,500 kilometres north-east of Perth, the town of Marble Bar, through the Hamersley Mountains, Northwest Cape, Coral Coast, around Perth, Leeuwin Cape, and down to the southern part of the state above the Great Australian Bay.

The main feature that testifies to the high attractiveness of the natural values of the northern, driest parts of the above area is the unusual geological richness. Moving south-west from the Marble Bar along the Hamersley Range, rising above the grass-covered spinifex plains, you can admire the 3.5 billion-year-old landscape elements, which for centuries were shaped by the sculptural activity of wind and water (Smith, Citation2000). Unique geological heritage sites can be found in the national parks: Karijini, Millstream-Chichester, Kalbarri or Mount Augustus National Park, which is famous for the largest isolated rock monolith in the world. The rock formations known as stromatolites on the hills around Marble Bar are examples of the earliest known forms of life on Earth. The same rock formations can also be found in Western Shark Bay, which is part of the UNESCO World Heritage site. The waters of the bay are home to the largest population of marine mammals in the world, including whale shark, tiger shark and endangered coastal dugong. A popular attraction of Shark Bay is the species of dolphin (bottlenose) (Miles, Citation2005). Another area that holds significantly increased attractiveness for tourists in this part of Western Australia is the second of the UNESCO natural areas – the coast and the Ningaloo reef, extending for 260 kilometres along the western part of the Exmouth Peninsula. Although, like Shark Bay, it is mostly a marine area due to the uniqueness of the protected landscape, it is also a popular destination for motorized tourists.

Very popular tourist attractions in terms of natural values are also found in areas located in the immediate vicinity of Perth. This is mainly due to the proximity of protected areas – there are 227 protected areas within 100 kilometres of the city centre that are convenient places for walks and hikes. Unlike the Kimberley Upland, the protected areas in this part of the state are much more numerous but occupy smaller areas (up to 15% of the area of the primary fields). This is due to the higher population density of this part of the state and to related agricultural activity. The Yanchep National Park is an area of 29 km2, built of limestone, in which there are seven caves forming a network of underground corridors. On the surface, along the routes leading through the park, one can meet some of the most characteristic representatives of Australian fauna – grey kangaroos and koalas, which are rarely found in Western Australia (www.parks.dpaw.wa.gov.au).

In the Nambung National Park, located about 160 kilometres north of Perth, there are characteristic rock outcrops (pinnacles). These limestone formations are scattered over 190 km2 and resemble carved columns, creating a magnificent landscape, which is the result of weathering and erosion processes (Maik, Citation2003). Other natural tourist attractions in the Perth region include the John Forrest National Park, famous for its two waterfalls (Hovea and National Park Falls) and the only island considered in the study – Rottnest. Due to its proximity to the city – just 19 kilometres from the Fremantle seaport – the island is a particularly popular destination for trips among residents of the Perth area (Miles, Citation2005).

The attractiveness of areas located to the south and south-east of Perth is attributed to the forest, which is the largest in Western Australia. With the decrease in the average annual air temperature and the increase in the annual rainfall, areas covered with grass, characteristic of the central and middle-western part of the state, turn to forests. The south-western and southern areas of the state are covered with deciduous forests and alternating green thickets with a varied shoreline of eucalyptus trees, casuarinas, honeysuckles and wild orchids (Maik, Citation2003). As noted by Smith (Citation2000, p. 130), it is ‘one of the most picturesque and green areas in Western Australia’. In this area the tallest trees in the world can be found – the multi-coloured eucalyptus (karri), reaching a height of 90 metres (Smith, Citation2000). In the area around Pemberton, tourists can climb the trunk of one of these to a viewing platform located at a height of 60 metres. Closer to the southern coast of the state is the Walpole-Nornalup National Park with various varieties of eucalyptus to be seen while walking beneath the crowns of trees in the Valley of the Giants. One of the most popular tourist attractions of the south-western part of the state is Wave Rock. Located about 200 kilometres north-west of Ravensthorpe, the formation rises 15 metres above the surrounding plain, giving the impression of a fossilized sea wave. The Wave Rock formation is an example of granite erosion, and the process of its creation dates back millions of years (Maik, Citation2003). The lowest level of attractiveness in terms of natural values in Western Australia is marked by basic fields located in the central part of the state. The largest Australian desert areas are located here: Desert Tanni, Great Sandy Desert, Small Sandy Desert, Gibson Desert and Great Victoria Desert. The map showing the valorization of anthropogenic elements of Western Australia was presented slightly differently than that of the valorization of natural elements. The parts of the state that score very high or high attractiveness include ten out of 300 basic fields, which is only 3% of the region studied. Fields with very low and low attractiveness make up as much as 91% of Western Australia. The remaining area is occupied by units with an average level of attractiveness. In contrast to natural values, there is a higher concentration of anthropogenic elements, and their arrangement can be observed in connection with the distribution of the settlement network.

The tourist attraction that scored the highest in terms of anthropogenic values is to be found in one major region, which is the area covering the city of Perth and its immediate surroundings. Perth is the largest city in Western Australia. The area of less than 6,500 km2 is inhabited by about two million people, making Perth the fourth largest city in Australia. The capital of Western Australia is the most isolated city of this size in the world – the nearest city with more than a million inhabitants (Adelaide) is located 2,700 kilometres away (Maik, Citation2003). Despite its geographical isolation, Perth is a city willingly visited by tourists, including caravan tourists. In 2018, the city was the third largest traffic destination for foreign tourists who decided to undertake a caravanning trip in Australia (Caravan Industry Association of Australia, Citation2018). For this reason, Perth is often referred to as the ‘west gate’.

Perth’s high tourist attractiveness is due to having the largest number of tourist facilities in the state. It is the cultural capital of Western Australia. Within a radius of 100 kilometres from the city centre, there are 84 out of the 165 museums and art galleries included in the study, including those ranked most important in the state: the Western Australia Museum, the Western Australia Maritime Museum and the Art Gallery of Western Australia, which present exhibitions and collections from colonial times, contemporary times, as well as elements from Aboriginal culture. There are also many objects in the city and its vicinity whose history dates back to the period of its formation in 1827. The most interesting in this respect is the city centre, which despite its reconstruction in the 1970s still contains many examples of colonial architecture from the nineteenth century (Miles, Citation2005). The most important of these include the first seat of the Governor of Western Australia, built from 1859 to 1864, Government House; Deanery building from 1859; Old Fire Station (nowadays the seat of the Fire Brigade Museum) dating from the late nineteenth century; the Christian cathedrals – St George’s Anglican Cathedral and St Mary’s Roman Catholic Cathedral; and the Perth Mint, the oldest mint still functioning to the present day, from 1899. Along one of the main streets of the city – St Georges Terrace – you can also admire the town hall building, which dates from 1870, the remains of the barracks, from 1863, and the buildings of old schools from the mid-nineteenth century (Cloisters and Old Perth Boys’ School). The city of Fremantle, located in the southern suburbs of Perth, also has a high level of attractiveness for tourists (Miles, Citation2005). The main attraction of the city is the prison founded in 1855 – Fremantle Prison. The prison building, currently a museum, is the only Western Australian cultural site inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

An additional criterion determining the tourist attractiveness of the Perth region, which is particularly important in terms of caravan tourism, is the offer of a camping base, the best developed in Western Australia. Travellers in this part of the state benefit from 244 campsites located in caravanning sites within a radius of 200 kilometres from the centre of Perth. Of these, 104 are sites of the highest standard (caravan parks) offering a variety of facilities. The largest number of tourist information points is also available to tourists here.

Outside the Perth region, and among the most interesting in terms of anthropogenic values of Western Australia, it is worth mentioning smaller, regional urban centres, such as the resorts along the coast, Broome, Karratha, Carnarvon, Geraldton, Albany and Esperance, and the old gold mining centres, Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie, famous for wide streets and well-preserved buildings reminiscent of the gold rush.

As in the case of natural values, the least anthropogenic regions of Western Australia are the desert areas of the central part of the state. The Aboriginal reserves located here are the only factor influencing the tourist attractiveness of the northern and middle parts of the state. In many of them there are rock paintings to be admired, which are an expression of the indigenous culture of the continent for thousands of years on the territory of Australia (Maik, Citation2003). A separate map of the valorization of Western Australia in terms of transport accessibility allows us to determine the ease of access to particular areas of the state by potential tourists ().

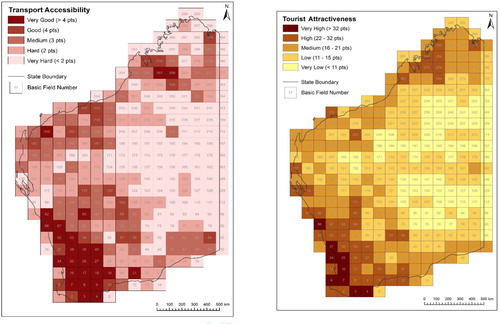

Figure 4. Assessment of transportation availability and summary assessment of tourist attractiveness of Western Australia. Source: authors’ own elaboration.

The availability of communications in the studied area shows quite a large variation. The south-western part of the state is clearly distinguished, a result of the arrangement of the network of road routes – the density of roads (including main roads for the most part) is the largest highest here and amounts to over 1,000 km per 10,000 km2. The most accessible part, containing the best communications, within the entire area is the city of Perth, which is the main hub of the state. Perth Airport is also the largest in Western Australia – serving around 14 million passengers a year (www.perthairport.com.au). The areas that are slightly less well connected are in the north-west and south-east of the state. Their availability was rated as medium or good. However, the most difficult access is to the least attractive desert areas located in the central part of Western Australia – the density of roads in the primary fields located in this part of the state rarely exceeds 250 km per 10,000 km2. The communication accessibility of the very attractive natural northern fragments of the Kimberley Upland is also difficult. It a few main roads, the most famous of which is the highway connecting Perth and Darwin (Perth to Darwin National Highway). The periodic floods occurring in the summer season also create a big obstacle for motorized tourists travelling in this part of the state.

The last part of the research was to create a map presenting a summary of the attractiveness of Western Australia for tourists. The assessment was obtained by calculating the sum of the points for natural and anthropogenic values and communication accessibility. The maximum number of points for all elements was 80. Bonitation values obtained by individual basic fields fluctuated from 5 to 51 points. Analyzing all the components, the final map of the valorization of tourism in Western Australia is closest to the map assessing the attractiveness of natural values. On the basis of the conducted research, it should be noted that in Western Australia the areas of medium and low attractiveness for tourists are in the majority, which together take up 60% of the state. The fields that make up these areas scored between 11 and 21 points, which indicates the lack of clear tourist values that would increase the attractiveness of the area.

Fields with very high and high attractiveness (minimum 22 bonitation points) cover 17% of the studied region. There is a general regularity in their distribution, which is because the vast majority of them are located at a distance of about 200 kilometres from the coast. It is clearly visible that the most attractive part is the south-western part of the state with the capital, Perth. The northern parts of the state are also of note (mainly due to their natural values). Tourist movement in Western Australia is therefore the most concentrated in the above areas. The least attractive areas (below 11 bonitation points) make up 23% of the area under study. They are located mainly in the central part of the region, and their low attractiveness is associated with the occurrence of vast desert areas in this region ().

Table 3. Tourist attractiveness indicator.

Tourist values and the distribution of the camping base in Western Australia

An inherent element of participation in any type of tourism is providing travellers with an appropriate infrastructure with accommodation services. The accommodation base is the most important element for tourism development, and enables not only satisfying basic living needs for tourists, but also the development of the tourist function of the area. According to Kowalczyk (Citation2000), the most important factors for the location of the accommodation base are landscape attractiveness, favourable climate, presence of water reservoirs, rich vegetation, occurrence of wild animals, access to the beach and the sea. It can be assumed that the above-mentioned features largely apply to caravanning tourism, in which campsites are of primary importance for tourists travelling by motorhomes, campervans or caravans. Sala (Citation2015, p. 450) writes that ‘the great advantage of campsites is their location’. They are often located in the vicinity of the sea or near national parks with the opportunity to organize attractive trips. The valorization presented using the point bonitation method indicates that there are areas of very high tourist attractiveness in Western Australia.

Distribution of the camping base in Western Australia

Western Australia has a large tradition of caravan tourism and camping. The largest Australian state boasts a long-standing stable number of caravanning participants, among whom campsites are a popular form of accommodation. Just like in the rest of the country, tourists travelling through Western Australia can choose from facilities of very different standards: from paid campsites, offering a variety of services (caravan parks), to the most basic, free campsites (campgrounds). According to CitationWikiCamps Australia data, there were 7,354 campsites in operation in Australia in 2018. About 34% of these were campsites of the higher standard caravan park type. On a national scale, the region of Western Australia has an averagely developed camping base, comprising 16% of the facilities in Australia. Considering the area of Western Australia (33% of Australia’s area), the number of camping sites may seem small. However, it should be borne in mind that the area of the state is inhabited by only about 11% of the population of Australia, and a significant part of it is made up of the unpopulated or sparsely populated desert areas. For this reason, among others, the distribution of the camping base in Western Australia is very uneven – the density of campsites in total is 0.5 objects per 1,000 km2, which is one of the lowest in Australia. Calculated per 1,000 inhabitants, the number of campsites in Western Australia is higher than in the most densely populated states of the country (Victoria; New South Wales) ().

Table 4. Camping base in Australia in 2018 according to type.

Camping facilities of a higher standard – caravan parks – are the most often used in Western Australia. Among the most important advantages of this type of accommodation, tourists mention such factors as: a more favourable price offer, and thus the possibility of a longer rest compared to other types of accommodation; the leisurely family atmosphere adopted in the camp; the benefits of outdoor activities; and the attractive location. Security and social aspects are also important (the possibility of interaction with other campsite users). In 2016, the share of overnight stays provided by Caravan Park campsites in general out of the overnight stays spent by caravanning tourists in Western Australia was 66% among Australian tourists and 62% among foreign tourists (Caravan & Camping Visitor Snapshot, Citation2016). An inventory of the camping base of Western Australia was carried out and the authors decided to limit the study to this type of object only. In the analysed area, 376 caravan park campsites were identified, which accounted for 15% of this segment in Australia and 32% of the total campsite base in Western Australia. As mentioned above, the uneven distribution of camping facilities in Western Australia is noticeable. Considering the division of the state into tourist regions, the largest number of campsites were in three of the smallest areas in 2018: Experience Perth, South West and Coral Coast. They gathered a total of 211 objects, which constituted 56% of the total. This means that the remaining two regions (much larger in area) included a total of 165 objects. In the two largest regions of the state – Golden Outback and North West – the density of campsites was very low and amounted to only 0.1 object per 1,000 km2. In comparison, in the smallest region (Experience Perth) the value reached 1.6 objects per 1,000 km2 ().

Table 5. Density of campsites in the tourist regions of Western Australia in 2018.

Characteristics of the camping base in Western Australia

An important factor that proves the attractiveness of camping fields is the range of facilities offered by them. Campsite availability in terms of the needs of caravan travellers, for whom a camping stay is often only a part of a longer journey, can play a decisive role in choosing a given object as a stopover and for accommodation. A study conducted by Tourism Western Australia on a group of people participating in caravan tourism suggests that in addition to the price and attractive location of a campsite, caravan tourists also appreciate more specific amenities, such as the general appearance of the facility (understood as the cleanliness of the facility and the attractiveness of its surroundings), a sufficient number and size of camping sites, access to shady places, a waste disposal site, the presence of basic sanitary facilities (toilets, shower cabins) and their cleanliness, and access to and the cleanliness of a camp kitchen.

Using data from CitationWikiCamps Australia, the study examined to what extent Western Australian campsites were prepared to meet the expectations of caravan tourists. Following the above-mentioned tourist indications and the specific nature of caravan tourism, according to the availability of data, 24 criteria were selected describing the range of services offered by campsites. The Western Australian camping fields are best prepared for handling caravan tourists in terms of the availability of basic pieces of equipment. All of the 376 facilities have sanitary facilities in the form of toilets and shower cubicles, and the vast majority of them also offers access to electricity, drinking water and barbecue facilities. Taking into account the position of the camp, as much as 92% of campsites allow you to erect your own tent on the premises. Access to shady positions and the possibility of accommodation in a tourist lodge is also common. Interestingly, 85% of facilities welcome people travelling with pets. Less favourable camping sites in Western Australia are rated thus in terms of location and this is partly related to the possibility of organizing attractive trips and recreational activities. Although almost half of them are located in an attractive environment, only about one third of the facilities have a playground for children, are located near hiking routes or areas favourable for fishing. The facilities least frequently found on Western Australian campsites, which are important for caravanning tourism, are a location in a national/state park, a location near bicycle routes and routes for four-wheel-drive cars, and a car wash.

When Western Australia is divided into tourist regions, there are some differences in the percentage of campsites with selected facilities in particular areas. The biggest differences relate mainly to the less popular elements of camping equipment (camp kitchen, tourist cottages, playground, place for dumping waste), which are usually more common in campsites in regions with higher density campsites (Experience Perth, South West, Coral Coast). Relatively large discrepancies also apply to elements describing the location of facilities – especially in the case of locations close to angling areas, where the difference between the percentage of campsites in the most attractive and least attractive areas in this respect is 44 percentage points. It is also worth noting that facilities rarely found in campsites, such as the possibility of refuelling vehicles and car washes, are more characteristic of objects located in regions with the lowest density of campsites (North West, Golden Outback), in which campsites are often located at a considerable distance from larger urban centres.

Considering the number of facilities, camping sites in Western Australia had an average of 13 of the 24 items taken into account in 2018. There were no significant differences in the average number of facilities found on campsites in individual tourist regions of the state. It is worth noting that in the audited year in Western Australia, most had 11–15 (58%) of the facilities in question. Sixty-two campsites offered travellers more than 15 of the facilities identified in the study (only one of them offered more than 20 facilities). The highest average number of places was offered by campsites in the North West region (146 places per facility), whereas in the Experience Perth region the average number was 47 places (Tourism Western Australia, 2007). One of the main goals of the work was to examine the relationship between the distribution of tourist values and the location of the campsites in Western Australia. In order to verify the research hypotheses set forth in the introduction, we checked whether a relationship existed between the location of the campsites and that of natural values and between the location of the campsites and that of anthropogenic values and how strong they were. How strong the relationship was between individual natural and non-natural values and the number of camping fields was also determined, which gave an indication of what elements in the distribution of the campsite base in Western Australia were connected to the greatest extent.

In order to analyse the relationship between the studied features, the Pearson correlation coefficient was used. The main factor in using this method was the number of research units, which amounted to 300. According to the assumptions, the advantage of using the Pearson correlation coefficient for large samples is a lesser burden of error (Norcliffe, Citation1986). Before making separate calculations for natural and anthropogenic values, the value of the Pearson correlation coefficient for the overall tourist attractiveness (including communication accessibility) and the distribution of the campsite base was calculated to check the strength of the relationship between them. The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.748, which means there was a significant relationship between the variables. In terms of caravanning tourism, Western Australia has well-developed tourist functions. Although only selected fragments of the state are characterized by high tourist attractiveness, the calculated Pearson correlation coefficient indicates that the largest number of camping fields are in the areas where it is the highest. Western Australia is perceived as an attractive place among caravan tourists. The Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.486, indicating the existence of positive moderate dependence between the studied variables. In the next step, the correlation values between the distribution of the campsite base and individual nature values were calculated ().

Table 6. The relationship between natural values and the distribution of camping grounds in Western Australia.

It can be seen that the strongest relationship occurs between the distribution of the campsites and the number of geological heritage objects. This is a positive correlation and the relationship between moderate features. The increased occurrence of elements of an inanimate nature, unique for Western Australia, with significant geological and educational value, therefore affects (increases) the number of campsites located near them. The location of the campsite is also favoured by the distance from the shoreline (also moderate positive dependence) and to a lesser extent forest cover, measured by the length of the forest shoreline and the value of annual rainfall (positive and low dependence in both cases). There is also a linear negative relationship between the distribution of camping facilities and the average annual air temperature. Although this is a low dependency, it indicates that for campsite locations, areas with lower average annual air temperature are more convenient. In the case of other components of natural values, there is practically no connection with the distribution of campsites.

The relationship between anthropogenic values and the location of campsites

According to the hypothesis put forward in the introduction, anthropogenic values are not the main reason caravan tourists decide to travel to Western Australia. They shouldn’t, therefore, to any great extent determine the location of the state campsites. The value of the Pearson correlation coefficient was 0.872, which indicates a significant positive relationship between the variables. The correlation was statistically significant at the 0.01 level. The obtained result does not confirm, therefore, the partial hypothesis, according to which the distribution of the campsite base in Western Australia is determined to a greater extent by natural values. At the correlation coefficient for anthropogenic values calculated above and the distribution of the campsite base, it can be concluded that the non-environmental attractiveness is of greater importance. As in the case of natural values, the strength of the correlation between the distribution of campsites and the individual components of anthropogenic value (determined by the point bonitation method) was also checked. The calculations did not take into account objects inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, which is conditioned by the fact that there is only one such facility in Western Australia ().

Table 7. The relationship between anthropogenic features and the distribution of campgrounds in Western Australia.

It can be seen that the Pearson correlation coefficient values are less diversified than in the case of natural values. With the exception of the area of Aboriginal reserves, where a negative value and the lack of a linear relationship between the examined features were found, calculations for the remaining elements indicate a positive relationship (from moderate to significant). Among the anthropogenic values, the dependence on the location of the campsite is evident due to the number of tourist information points and the number of historical objects.

Based on the calculations carried out, it has been proven that there is a significant relationship between tourist attractiveness and the location of campsites (Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.748) in Western Australia. The largest number of campsites is located in the Experience Perth, South West and Coral Coast touring regions and accounts for 56% of the total camping base. According to the point bonitation method, the above regions are also the most attractive for caravan tourists travelling through the state. The hypothesis that ‘in Western Australia there is a high correlation between the tourist attractiveness and the location of the campsite’ and ‘the largest number of campsites are in the areas with the highest tourist attractiveness in Western Australia’ can therefore be considered as confirmed.

Another research question posed in the introduction was: does the deployment of the camping base in Western Australia determine to a greater extent the natural values or anthropogenic values? The dominant role in the distribution of the camping base of the state is attributed to anthropogenic values (Pearson ratio 0.872). Therefore, the hypothesis should be considered unconfirmed. A much more correct assumption would be, however, the formulation that anthropogenic values have a greater impact on the distribution of camping fields.

Attempts to answer the question of why the hypothesis has not been confirmed can be found by examining several factors. To the lower than in the case of anthropogenic values for natural values and the location of the campsite is mainly due to the very low number of campsites in the Kimberley region. According to the study, the Kimberley Plateau is one of the most attractive natural parts of Western Australia. Deprived of larger urban centres, inhabited mainly by Aboriginal communities, it does not attract as many tourists as the south-western parts of the state. This causes the slow development of the camping base. In the area occupying approximately 420,000 km2 (16% of the state area) there are only 35 campsites, which is only 0.08 per 1,000 km2. The great difficulty for the development of the campsite base and tourism in the Kimberley region is limited transport accessibility and climatic conditions. During the rainy season (from November to March), the area is sometimes impassable (Hinze, Citation1997). Undoubtedly, an important limitation for the development of the campsite base in valuable natural areas (both the Kimberley Upland and the rest of the state) is also the fact that these areas are one of the last to remain almost untouched by humans in Australia. Therefore, they should be protected in a special way from progressing anthropopressure. In relation to the question, ‘which natural values have the greatest impact on the distribution of the campsite base in Western Australia?’, in the case of distance from the shoreline, a correlation value above 0.4 was obtained, indicating a positive moderate relationship between variables. The number of camping fields decreases with the distance from the shoreline. It is worth noting that a similar situation takes place in the case of tourist attractiveness. It has been shown that in the case of elements describing the climate, dependence on the distribution of campsites exists but is low (positive for the annual sum of rainfall and negative for the average annual air temperature). The above hypothesis can be considered only partially correct. The majority of the correlation values in the case of natural values turned out to be lower than in the case of non-natural values. The strongest relation to the natural values of the campsites was obtained for the number of geological heritage objects (moderate positive relation at the level of 0.529). It can be assumed that this is due to the large accumulation of this type of object near Perth, in the vicinity of which the largest number of camping fields exist. It is difficult to assess, however, if such a strong relationship results from the great interest of caravan tourists in geological heritage.

Summary and conclusions

Caravan tourism is a type of tourism that, together with camping tourism, is an attractive way to relax for those who want independence, adventure and tourism movement. By using your own means of transport caravan tourism allows you to travel to places that are difficult to reach using other types of tourism. Caravanning is a particularly popular way of spending free time in Australia, where after World War II, it became a dynamically developing area of motor tourism. The above work concerns the issue of caravanning tourism in the largest state of Australia, namely Western Australia. The main purpose of the work was to indicate the most and the least attractive in terms of caravanning tourism areas in Western Australia and the study of the relationship between the tourist attractiveness and the location of the campsite. The valorization of tourist attractiveness of Western Australia, performed using the point bonitation method, has shown that the majority of the state falls into the medium range and is not very attractive. A large part of these areas are vast desert that, in line with the criteria set, are characterized by low tourist values. It was found that the parts of Western Australia most predisposed to caravanning tourism are areas with a large number of geocomponents and a high number of anthropogenic values. They are located in the vicinity of the capital, Perth, which is also the largest city of the state. The more attractive parts of the surveyed area also include the Kimberley Upland located in the north (especially in terms of natural values) and areas located up to approximately 200 kilometres from the shoreline.

The value of the coefficient was calculated which indicated a significant relationship between the analysed variables. This allowed us to confirm the hypothesis that in Western Australia there is a high correlation between tourist attractiveness and the location of the campsite. The largest number of camping fields are in the most attractive tourist areas. Whether the distribution of a camping base in Western Australia is more related to the occurrence of natural or anthropogenic factors was also checked. Based on the calculations, it can be concluded that the Pearson correlation coefficient for natural values does not confirm the hypothesis put forward in the introduction, according to which the distribution of the camping base in Western Australia is determined by natural values to a greater extent. The best example of this is the area of the Kimberley Upland, where, with very high natural attractiveness, only 35 out of 376 campsites identified in the study are located. Analyzing individual natural values, it can be seen that the greatest impact on the camping sites in Western Australia is the number of geological heritage objects and the distance from the shoreline, which is a partial confirmation of the last hypothesis put forward in the introduction.

It should be mentioned that the correlation in relation to anthropological features is influenced by the existence of campsites and information points, which can be close to campsites and man-made features. The location of campsites may come first, and the information points created afterwards. And, of course, it should be stated that some of the anthropological features such as amusement parks (which were not included in this analysis), or thematic museums, may have opened after the campsite was set up. When tourism destinations start to be recognizable domestically or even internationally, many other investments are made. Other cultural facilities may choose to invest because of the recognized tourism brand of a location and these are developed close to such destinations. Similarly, other hotel facilities and campsites may be set up after these investments have been developed. This is why such a correlation can occur at both sides.

The value of the Pearson correlation coefficient for anthropogenic values indicates that non-natural elements have a stronger impact on the distribution of the Western Australian camping base. However, it should be remembered that some of the investments in anthropogenic values may have be made because of the high value of the tourism movement, so the correlation can occur in both directions. The dependence between anthropogenic values and the location of campsites is so strong because most of the elements considered in the study are located in the area of the most important urban centres (including Perth, in particular). There is a noticeable trend, therefore, showing that the number of campsites in Western Australia is increasing near cities and areas with a high population density. The research shows that Western Australia has a great tourism potential. Despite barriers in the form of vast desert areas in the central and eastern parts of the region, as well as the insufficiently developed communication infrastructure and campsites in the northern part, the unique values and protected status of significant areas of the state make Western Australia a convenient place for practising low-invasive forms of tourism, which can include caravan tourism.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 It should be noted that some information points are created close to campsites.

2 The presence of campsites as two of the eight elements used to establish the level of manmade attractions in a specific area makes the correlation coefficient higher.

References

- www.tourism.wa.gov.au/Publications%20Library/Research%20and%20reports/Caravan%20and%20Camping%20Snapshot%202016.pdf (3.07.2017)

- www.caravanindustry.com.au – Caravan Industry Association of Australia (14.12.2018)

- www.environment.gov.au/fed/catalog/main/home.page – Australian Government, Department of the Environment and Energy (19.11.2018)

- www.polskicaravaning.pl – Polski Caravaning (30.05.2019)

- www.westernaustralia.com – Tourism Western Australia (8.04.2019)

- www.perthairport.com.au – Perth Airport (10.04.2019)

- American Camper Report. (2017). Coleman, outdoorindustry.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/2017-Camping-Report__FINAL.pdf (3.07.2017).

- Australian Government, Department of the Environment and Energy. Retrieved November 19, 2018, from www.environment.gov.au/fed/catalog/main/home.page

- Beilharz, P., & Supski, S. (2017). A sociology of caravans. Thesis Eleven: Critical Theory and Historical Sociology, 142(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513617727892

- Brooker, E. (2011). In search of entrepreneurial innovation in the Australian outdoor hospitality parks sector [Unpublished PhD thesis], Griffith University, Gold Coast.

- Brooker, E., & Joppe, M. (2014). A critical review of camping research and direction for future studies. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 20(4), 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766714532464

- Brooker, E., Joppe, M., Davidson, M. C., & Marles, K. (2012). Innovation within the Australian outdoor hospitality parks industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 24(5), 682–700. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111211237246

- Caldicott, R. (2011). Supply-side evolution of caravanning in Australia: An historical analysis of caravan manufacturing and caravan parks [Honours thesis, Southern Cross University, Lismore].

- Caldicott, R., & Scherrer, P. (2013). Facing divergent supply and demand trajectories in Australian caravanning: Learning from the evolution of caravan park site-mix options in Tweed Shire. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 19(2), 117–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766712457672

- Caldicott, R., Scherrer, P., & Jenkins, J. (2014). Freedom camping in Australia: Current status, key stakeholders and political debate. Annals of Leisure Research, 17(4), 417–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2014.969751

- Caravan Industry Association of Australia. (2018). Retrieved December 14, 2018, from www.caravanindustry.com.au/