ABSTRACT

This study locates the COVID-19 pandemic in the realm of crisis management and by applying a novel paradox and sensemaking perspective, we illustrate how tourism organizations dealt with tensions between maintaining business as usual and preparing for the uncertain in the midst of an imminent winter season. We argue that it is not so much the novelty of the COVID-19 crisis per se but the paradoxes it created that should be considered if we are to understand how the crisis management of organizations unfolded in practice. We zoom in on the ad-hoc crisis management practices of small and medium-sized enterprises which have barely been analyzed through the lens of how they handled the pandemic and address this gap from the perspective of employees on the frontline. Using 22 interviews with regular and seasonal employees as a database, we show how employees perceived organizational attempts to manage the crisis and explore the interplay between organizational responses and employees’ individual sensemaking/sensegiving attempts for coping with a paradoxical situation. Our contribution emphasizes paradox recognition as a critical sensemaking outcome for navigating an extraordinary crisis situation. The implications highlight several measures for coping with crises and securing operations once they are over.

1. Introduction

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit Europe in early spring 2020, it created a situation for tourism and hospitality organizations in Alpine winter sports destinations that can be described as paradoxical due to competing demands (Smith & Lewis, Citation2011). On the one hand, the season was peaking with excellent weather conditions towards the Easter break, encouraging businesses to run at full speed. On the other hand, a novel and highly contagious virus was spreading across the continent, creating a pressing need for restrictive health and safety measures. In this short transition period from pre-pandemic tourism to a new pandemic era (Chi et al., Citation2021), operational tensions accelerated particularly for frontline employees (FLE), including frontline service sector managers (FLSSM) whose job roles are characterized by direct customer interaction (Vo-Thanh et al., Citation2020), their everyday experiences of dealing with the indeterminacies of those interactions within the servicescape (Gabriel, Citation2009) and their structurally weak position in the customer-employee-employer triangle (Bolton & Houlihan, Citation2010; Schneider et al., Citation2021). While previous employee-related research on the pandemic illuminates what happened to the industry’s FLEs in terms of socio-economic and health-related effects (Baum et al., Citation2020; Karatepe et al., Citation2021; Sigala, Citation2021; Vo-Thanh et al., Citation2020), we turn to them as knowledgeable actors who made crisis management happen.

As the pandemic notably intensified the practical difficulties of interactive service work, it put frontline jobs in the spotlight where they received a public re-evaluation from stigma to hero status (Mejia et al., Citation2021). Almost overnight, the job of FLEs in the hospitality and tourism industry – like those of many essential service employees such as supermarket workers and bus drivers – turned into a balancing act of providing ‘business as usual’ and of implementing the necessary safety measures for customers and themselves (Pradies et al., Citation2021). Given the unprecedented situation of the first pandemic in a globalized world, what is deemed possible and necessary (and available) became the subject of continuous cycles of learning by doing and redefinition. In consequence, knowing what to do was widely experienced as a joint activity and exemplified the idea of knowledge ‘as taking place in work practices’ (Gherardi, Citation2009, p. 353). In this regard, FLEs involuntarily became knowledgeable actors of organizational crisis management and, in this new role, had to make sense of working within a new set of competing demands to protect their organizations from paralysis.

As extraordinary tensions are omnipresent and affect each and every one of us, paradox theory is increasingly being applied to understand how people experienced life and work during this pandemic (Carmine et al., Citation2021; Collings et al., Citation2021; Pradies et al., Citation2021). Paradox meta theory traditionally builds on the premise that organizations and their behaviours are to a large extent characterized by the tensions faced from within and from the environment (see Keyser et al., Citation2019 for a review) and seeks to impede the conceptual oversimplifications of ambiguous relations and messy realities (Schad et al., Citation2016). Paradox research shows that organizations can find both constructive and insufficient ways to respond to such tensions (Jarzabkowski & Lê, Citation2017; Lewis, Citation2000) and that the key for successful tension management is balancing (both/and) rather than solving (either/or) competing demands (Sutherland & Smith, Citation2011). A new focus in paradox research is FLE responses to organizational tensions (Schneider et al., Citation2020), which helps articulate the complexity of and the skills involved in the everyday practices of interactive service work (Schneider et al., Citation2021). Our study theoretically contributes to this burgeoning stream of research by adding the layer of extraordinary circumstances as paradoxes tend to increase in salience in dynamic environments such as the COVID-19 pandemic due to the pressure for action and the high level of uncertainty associated with doing the right thing (Carmine et al., Citation2021; Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013).

Tourism and hospitality organizations have a special responsibility during a pandemic (Chi et al., Citation2021) because hosting international tourists risks spreading contagious diseases. For example, at the beginning of the pandemic tourism and hospitality organizations from the Alps helped accelerate the spread of the COVID-19 virus across Northern Europe. It is, therefore, vital to gain a better understanding of how small and medium-sized tourism and hospitality organizations can effectively manage such a situation. Given the peculiarities of the industry’s structure especially in rural areas, this is a chance to deepen the scarce understanding of how smaller organizations, often family firms, generally deal with and learn from crises (Herbane, Citation2010; Stoker et al., Citation2019) and respond to challenges related to COVID-19 (Bartik et al., Citation2020). In this context, the objective of this study is to provide insights into how crisis management unfolds in practice. We argue that, in order to really understand the practical realities of handling a pandemic such as COVID-19 ‘on the ground’, we must look at FLE micro-level practices, their teachings and the distributed agency in managing unresolvable tensions (Jay, Citation2013, p. 140).

Seasonal work in the tourism and hospitality industry can be tough and working under increased tensions can be a make-or-break experience for remaining with or returning to an employer. Given the general shortage of qualified service employees in many Western tourism destinations, we are thus particularly interested in how employees perceived intraorganizational processes of COVID-19 crisis management and how these perceptions fed back to their employment and industry image. Combining sensemaking and paradox theory, we explore how employees acquired new responsibilities and infused them with meaning in order to tackle the invading uncertainties. Furthermore, we show what paradox and sensemaking theory can offer as an alternative lens to more linear concepts as a means of understanding the crisis emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Theoretical background

Sensemaking (Weick, Citation1988) has become a quasi-paradigm of organizational research (Maitlis & Christianson, Citation2014) and encompasses the actual activity of plausibly interpreting social reality. Since social reality is in flux, ambiguous, and messy (Tsoukas & Chia, Citation2002), individuals, groups, and organizations as systems regularly need this inner feedback process that creates a possible mental ‘map’ about ‘how things work’ in the world out there in order to develop a coherent sense of self and to remain capable of action (Weick, Citation2001). Sensemaking not only helps to order past experiences but can also be useful for anticipating upcoming situations (Vuori, Citation2013).

Although sensemaking has been intensively studied in the context of planned change initiatives in organizations (Helpap & Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Citation2016; Rouleau, Citation2005), including the sensegiving activities of change managers as attempts to redefine organizational reality (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991, p. 442), studying sensemaking is not primarily about the ‘big things’. Instead, it focuses on ‘the subtle, the small, the relational, […] the particular’ of ‘organizing as the experience of being thrown into an ongoing, unknowable, unpredictable streaming’ to find out how something like an event becomes meaningful and what the meaning of the story is (Weick et al., Citation2005, p. 410). Sensemaking involves both inter-personal and intra-personal processes, the latter often resulting in differing accounts of social reality (Steigenberger, Citation2015), depending on what cues from the environment and what frames of reference are used in the interpretations (Maitlis & Sonenshein, Citation2010).

2.1. Sensemaking of paradoxes

Paradoxes are defined as ‘contradictory yet interrelated elements (dualities) that exist simultaneously and persist over time; such elements seem logical when considered in isolation, but irrational, inconsistent, and absurd when juxtaposed’ (Smith & Lewis, Citation2011, p. 387). They are a central feature of modern organizations, for instance those arising between organizational efficiency and customer orientation but tend to accelerate in dynamic environments (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013). In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, paradoxes emerged due to the pressure for action and the great uncertainty of taking the right action (Carmine et al., Citation2021).

Paradoxes are studied as organizational phenomena yet they largely emerge in situated practices on the individual and group level (Jarzabkowski & Lê, Citation2017; Tuckermann, Citation2018). However, paradoxes need to be recognized before they can be acted upon (Lewis, Citation2000). Through the reflective process of sensemaking (Weick, Citation2001) people ascribe meaning to experienced tensions thereby transforming latent paradoxes into salient ones and vice versa (Jay, Citation2013; Lindberg et al., Citation2017; Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008). External events that interrupt organizational routines have the ability not only to trigger such sensemaking but also to have the potential to bring profound organizational change (Jay, Citation2013), for example, by increasing hygiene standards for years to come.

A paradox is constructed and situated between two opposing poles and the pushes and pulls between them (Gylfe et al., Citation2020). The management of paradoxes depends on the ability to embrace contradictory tensions (Lewis, Citation2000). In practice, however, organizations regularly get trapped by these tensions, ignoring them, remaining passive, or reacting to them by sticking to past routines (Jarzabkowski & Lê, Citation2017; Sparr, Citation2018). This has been referred to as the ‘paradoxes of learning’ (Lewis, Citation2000, p. 766), capturing the inability ‘to frame new knowledge within understandings, routines, and structures that enable actors to comprehend and adjust to variations’. The impact, scale, and pace of the COVID-19 pandemic is without precedent in contemporary economies and societies (Gössling et al., Citation2020) and thus, we argue that sensemaking enabled crisis management for many organizations but at the same time most likely created paradoxes of learning, triggering subsequent crises such as a severe shortage of staff who, during the pandemic, increasingly migrated to other industries where they are employed on better terms.

2.2. The role of sensemaking during a crisis

When literature refers to a crisis, it often addresses disastrous, devastating, and drastic events, which ‘disrupt(s) the orderly operation of the tourism industry’ (Laws & Prideaux, Citation2005, p. 2). According to Faulkner (Citation2020), a crisis refers to a ‘situation where the root cause of an event is, to some extent, self-inflicted through such problems as inept management structures and practices or a failure to adapt to change’ (p. 136). Crises result from unexpected issues which, when still on the horizon, are potentially manageable by organizations (Mair et al., Citation2016; Peters & Pikkemaat, Citation2005). In contrast, disasters are catastrophic, leaving little time to respond, and requiring management after the event has occurred (Laws & Prideaux, Citation2005).

The need for sensemaking is particularly high ‘in confusing situations, [in which] people develop a subjectively plausible story of what meaning, cause and consequence a certain development has and what an appropriate course of action would be’ (Steigenberger, Citation2015, p. 432). A sensemaking perspective on crisis management acknowledges that organizations do not simply respond to a threat, but that they enact the problem via their interpretations and subsequent actions (Maitlis & Christianson, Citation2014; Weick, Citation1988). This can go rather unnoticed as ‘small events are carried forward, cumulate with other events such as the shortage of skilled labour, and over time systematically construct an environment that is a rare combination of unexpected simultaneous failures’ (Weick, Citation1988, p. 309). In other words, dealing with a crisis is performative, creates the crisis’ environment, and therefore often intensifies it. Enacted sensemaking includes the creation of paradoxes, first and foremost because a situation is oversimplified (Lewis, Citation2000).

Crisis literature acknowledges the need of different organizational activity phases for effective crisis management (Ritchie, Citation2009; Weick, Citation1988) that ideally enable an improved post-crisis state. Most recently, based on previous literature by Ritchie (Citation2009), Mair et al. (Citation2016, p. 2) summarized three steps for tourist destinations, including ‘planning and preparedness activities’, followed by ‘response/management’, and ‘final resolution to a new or improved state’. Applying a three-step process-based view of a crisis (Mair et al., Citation2016) helps to shed more light on employees’ individual experiences in these phases, and to explore employees’ sensemaking also in paradoxical environments.

3. Material and methods

Comparing previous work on tourism hospitality employees during the pandemic (Demirović Bajrami et al., Citation2020; Park et al., Citation2021), only a few studies have used a qualitative perspective (Stergiou & Farmaki, Citation2015) to understand FLEs’ and FLSSMs’ sensemaking and exceptional experiences during COVID-19 events. We chose a qualitative research design for two reasons. First, our theoretical underpinning implies a qualitative approach because sensemaking is by definition a subjective process of interpretation (Weick, Citation1988). Second, the lack of research on employee experiences of crisis management in small and medium-sized enterprises necessitates a more in-depth understanding (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2020).

3.1. Research context

In this study, we focus on the crisis management experiences of FLEs and FLSSMs working in Alpine winter sports destinations. This context represented a prominent environment during the first wave of the COVID pandemic in 2020. Global headlines and later research showed that hundreds of cases across Northern Europe (almost all of them in Iceland and Norway) could most likely be traced back to infected staff at a ski resort bar in Ischgl in the Austrian Alps (Falk & Hagsten, Citation2021; Mayer et al., Citation2021). Soon afterward, the Austrian state of Tyrol ended its ski season early on the sunny Sunday afternoon of 15th March 2020. Effective immediately, slopes were evacuated, international tourists were required to return to their home countries, and Tyrol and Austria as a whole went into the first seven-week lockdown (Independent Commission of Experts, Citation2020). COVID-19 grew into a crisis in the Austrian Alps, triggering locally unmanageable incidents, disrupting the functioning of basically all tourism-related systems and rendering infrastructure, employees and services redundant.

Tourism in the European Alps, particularly winter tourism in Tyrol, Austria has created prosperity in many rural communities there (Fuchs & Weiermair, Citation2011), giving rise to winter sports/tourism destinations such as Ischgl, Sölden, or Arlberg. These were some of the superspreading destinations of COVID-19 throughout Europe (Gössling et al., Citation2020). In 2018/2019, Tyrol accounted for 49.6 million overnight stays and 12.4 million arrivals and generated about 17% of GDP through tourism (Tirol Werbung, Citation2019). However, the crisis caused a shock to regional labour markets, increasing the unemployment rate to 12.9% (a 4.7% increase compared to March 2019) and leaving 1.3 million people temporarily or completely laid off (AMS, Citation2021). This exposed the vulnerabilities and the societal and economic relevance of Austrian tourism, clearly seen in its unemployment rates increasing by 98.4% compared to the previous year (AMS, Citation2021). To make matters worse, this crisis hit employees of an industry well-known for non-standard and non-contingent employment arrangements (Martins et al., Citation2020).

With increasing dependency on tourism in rural destinations, the effects of crises, especially disasters, became more critical (Aliperti et al., Citation2019). In recent history, Tyrol has been hit by several natural disasters such as avalanches (Peters & Pikkemaat, Citation2005) and therefore has well-developed contingency plans and regulations on the state level to respond to natural disasters (Land Tirol, Citation2020). However, unlike some other parts of the world, global epidemics were a new threat, and unprecedented until a decade ago.

3.2. Sample and data collection

The rapid developments and the closure of all tourism and hospitality businesses in Tyrol on 15th March 2020 led to several unexpected challenges in gathering data. In total, we collected 22 semi-structured interviews from April 2020 to May 2020. Due to travel restrictions and the imposing of quarantine, all interviews were conducted and recorded using digital tools such as Skype or Zoom. To gather our participants, we used information-oriented selection to ‘maximise the utility of information from small samples and single cases’ (Flyvberg, Citation2011, p. 307) and selected regular and seasonal FLEs and FLSSMs working in the hospitality industry until the imposed closure due to COVID-19. provides an overview of the 22 interviewees and highlights several characteristics.

Table 1. Sample overview.

Since many interviewees reported on sensitive issues around organizational practices associated with the management of the crisis, an essential aspect of conducting the interviews was establishing trust. By using a reflexive sensemaking perspective (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991), we maintained our observational role, primarily focusing on employees’ experiences related to the shutdown events, regardless of whether the organizations’ activities were perceived positively or negatively. Here, a sensemaking approach to critical incidents (Lundberg & Young, Citation1997) does not take a position but aims instead at understanding the inter-subjective struggles of interpreting social realities. The interview was guided by the work of Bean and Eisenberg (Citation2020), and asked interviewees to ‘tell us about their job and responsibilities’, ‘their experiences with COVID-19’, and ‘how they experienced the changes that have taken place’ (for the interview guideline see Appendix).

3.3. Data analysis

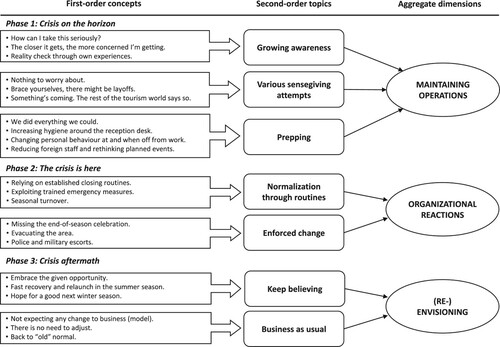

We followed the three-step Gioia methodology for analysis of the interview transcripts (Gioia et al., Citation2013). This methodology enables researchers to explore the data without establishing predetermined categories as it relies on systematic inductive coding (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991). First, we applied open coding to examine the underlying topics – as it turned out – while (1) the crisis was on the horizon; (2) the crisis was underway; and in the context of (3) the crisis’ aftermath. Applying a dynamic understanding of crisis (Mair et al., Citation2016) helped us to individually make sense of a myriad of codes in the open coding phase (Gioia et al., Citation2013). We developed the first order concepts in combination with ongoing discussions within the research team. For the second order themes, we used an iterative process informed by theoretical considerations (e.g. crisis reactions from Mair et al., Citation2016, or emotions during sensemaking, Helpap & Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, Citation2016) and cycled between concepts and themes leading to the creation of seven underlying themes which appeared theoretically saturated (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). While discussing and triangulating codes, concepts and themes, we revisited the data and revised the structure to achieve consensual interpretations (Gioia et al., Citation2013), which we distilled into the aggregated dimensions of ‘maintaining operations’, ‘organizational reactions’, and ‘(re-)envisioning’. These characterized employees’ sensemaking during the COVID-19 crisis. The data analysis procedure was supported by employing MaxQDA as QDA software. shows our analytical approach, moving from concepts to themes and aggregated dimensions.

4. Results

The following provides insights into employees’ experiences in relation to three phases, (1) the crisis on the horizon, (2) during the crisis, and (3) the crisis’ aftermath (Mair et al., Citation2016). Here we shed special light on employees’ sensemaking of organizational crisis management and the interplay between organizational responses, employees’ sensemaking attempts, and paradoxes recognized when dealing with the situation ().

4.1. Crisis on the horizon

Growing awareness: Awareness of the potential threat of an upcoming pandemic was limited among the interview participants until shutdown. The majority of interviewees reported their own and colleagues’ difficulties in taking incoming international press news on COVID-19 seriously. These news items were met with discursive coping strategies such as making fun of it (Chiara), repeating the keep calm mantra (Amalia) and downplaying the risk by juxtaposing the rural valley or village with the foreign nations of Iran, South Korea and China (Chiara). However, individual concerns started to grow the geographically closer and the more personally relatable COVID-19 became. For example, hearing of cases in neighbouring Italy and experiencing scarcity when searching for masks triggered a sense of alarm among the employees.

Well, at the beginning the handling was very relaxed and we actually made some fun of it. But when it was in Italy, which is very close, and later in Ischgl, which is just a stone’s throw away, we got kind of scared. I wondered what was coming towards us and what would happen. (Gernot)

Surprisingly, employees of local destination management organizations (DMO) admitted to not paying too much attention to potential major consequences (Michaela), although they were worried about how to deal with decreasing arrivals from e.g. Italy. In February, being profoundly affected by a pandemic and becoming a centre of its spread were still simply unimaginable (Jeanette). For example, when the first cases emerged in Ischgl, and led to the closure of single organizations, some interviewees from other destinations still thought that their locations could absorb the overflow business and profit from it.

We were following the situation in Ischgl, and had our contacts. But that we all were hit by it [imposed early season end] at once was unexpected. We were also naive enough to hope that we could still finish the rest of the season. That was pretty naive. (Richard)

It all started when I got a call from Icelandic guests telling me that they couldn’t come because^^ they would have to be quarantined upon their return to Iceland. I replied that we were receiving information on the virus from the WKO [chamber of commerce] every day. So I followed up with one of the guests and he sent me the link from the Icelandic health authorities indicating that they were not allowed to enter the country. (Chiara)

This also highlights the varying international dynamics of reacting to the virus’ global spread. In only one case did the management of a DMO provide employees with an early outlook at the beginning of March about what the upcoming weeks could look like:

We were given disinfectant by the company and were told that we would go into temporary layoffs or work from home. This was said from the beginning [in the first week of March] and we were also given an outlook about how long it would last. (Katrin)

What we did was to inform all the departments and employees about hygiene. We made sure that we had disinfectant dispensers for example at the reception because we have a lot of contact to the customers (…) We also did this at the public restrooms. (Anna)

A lot of the measures could have been taken earlier. We didn’t take it seriously and thought [COVID-19] wouldn’t come to us. We should have started to take it seriously earlier, even as early as at the big events in Sölden and the parties on the mountain. Nothing was taken seriously there. At a destination as big as Ischgl, I guess you just don’t want that to be true, so you play it down. (Johanna)

4.2. During the crisis

The crisis is here: For all interviewees, the crisis began with the decision to close down the ski resorts and this caused a huge shock. Therefore, every interviewee remembered the date of the imposed end of the season.

We didn’t expect having to actually close down. We had beautiful weather and lots of people on the terrace. The big challenge was what to do with the food, fresh fruit, and vegetables. Our supplier who runs a small company literally was crying on that Friday. He said if this [the shutdown] were really going to happen, then he [his business] would be dead. (Christoph)

The severity of the situation was emphasized by another employee, highlighting that the situation had nothing in common with previous events requiring the ski area to be closed due to e.g. wind or snowstorms. For Peter, it was a disaster to have to tell people to ‘go home’ despite the beautiful weather. Additionally, the closure also led to considerable additional organizational efforts not only for the management of internal resources, but also in processing cancellations, giving refunds and cleaning. An interviewee explained that the situation at the front desk of a ski resort was chaotic and even threatening:

When we got the message ‘we have to close’, that was insane. Some of the guests were so unhappy that I had to send two additional employees to the front desk because the staff felt threatened. (Maria)

We had eight Hungarian colleagues this season. They had to stop working a week earlier and returned to Hungary on Friday evening [immediately after the press conference] with buses they organized on their own. (Chai)

Other interviewees, on the other hand, reported several problems when employees and guests tried to return to their home countries. Situations ranged from ‘the guests decided to leave immediately, because who knows if there would still have been flights later’ (Stefanie) to observing that seasonal workers were accompanied by the military and/or police.

We organized buses so that they could depart, which also worked out fine. But it was a strange situation. I was there myself when the staff left and the military was there too with their weapons. That was a strange feeling. The military personnel were very relaxed, but to see so much police and military because of the departure of the employees was very strange. (Richard)

With the early termination of seasonal contracts, layoffs, and working from home, many businesses had no other option than to enter a kind of ‘hibernation’ and hope for better days ahead. Despite the negative consequences, some interviewees reported different ways of making sense of the situation, ranging from ‘spending time with our children because in winter we don’t really have any time to do this’ (Christoph) to balancing the damage with the benefits of the situation.

I could just relax and be a farmer. I could get away from all the high tech, from the machines, and really switch off for four or five weeks. Yes, the economic loss is huge, but from a human perspective, it was perhaps good. (Gernot)

Another disappointment was that the annual end-of-season celebrations were cancelled. However, instead of the typical farewell celebration ‘when the hotel closes at the end of the season, and they take you out to [or host] dinner’ (Saskia) employees needed to improvise, as explained by Jeanette:

We were all really sad that it ended so early, because this year had also been an incredibly awesome season and we were a truly awesome team. And among us employees, we had our own season-ending party then on Wednesday, because it was also the birthday of a colleague.

4.3. The crisis aftermath

Keep believing: As indicated, the financial losses on both company and personal levels were disastrous. Some interviewees, especially those from abroad, sat at home for weeks, leaving the entire family without income. Having no income or the possibility to receive social benefit payments, some became dependent on voluntary support from previous employers and friends to cope with the shutdown. On a financial level, the interviewees reported that businesses had to postpone investments, which also affected local contractors and suppliers.

Yes, we would have built a cableway this year. We’re talking about 25 million euros, and it was postponed until next year. Without this investment, the winter season should turn out fine. Otherwise, it will have to be postponed again. It [business in the region] all depends on it, starting with the local construction company and ending with the steelworkers. (Peter)

A frequent topic in the interviews was the lack of reliable information. Employees with financial (Maria) and managerial responsibility (Richard) claimed that the conditions and rules were constantly changing.

With layoffs, for example, the conditions change almost every day. That’s the real catastrophe, that you don’t have anything solid. For a while people were allowed to work at 30–40 percent, now only 10 percent. For myself, I like to work securely and predictably. I don’t want anything that isn’t right for me. (Richard)

Interestingly, in contrast to the scapegoating of Ischgl in the media coverage (Mayer et al., Citation2021), none of the employees ever blamed Ischgl or any other ski area for spreading the disease. When asked about what will change in the future, most interviewees were assured that the service itself will not change, making sense of this by underlining that their destination only had a limited amount of après-ski, and sold a high-quality service. An interviewee explained:

The Tyroleans have always been pioneers. I think it’s exaggerated that we now have to change something with the concepts that work. It’s the same with après-ski in Ischgl or Sölden. If it works, why fix it? I can’t imagine people not having a party anymore. Of course, this is only the case if things get better with COVID-19. (Christoph)

Sustainability was important for the interviewees. But the lack of fit between the demands of sustainable tourism and concepts that match existing business models also became apparent. High volumes of tourists will be needed to increase profits and reinvestment.

We hear a lot about ‘soft’ tourism and that you have to get to this or that, but we simply lack the way there. (…) We all know what’s currently being said in many places. There’s something being demanded but nothing to show for it. If you want to find different pathways for tourism, then show us the way there. From investment to returns on investment, all the way to the utilization of capacity, all of this will require us to have a certain number of guests in the village. (Richard)

5. Discussion

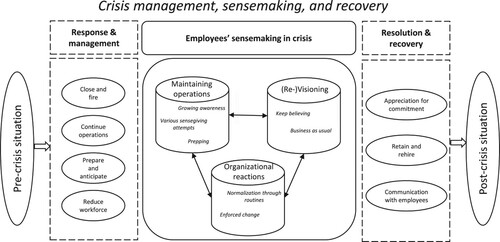

Looking back at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in Europe, the paradox between celebrating the winter season and preventing a highly contagious virus from spreading seems obvious. Yet, hospitality and tourism organizations, FLEs and FLSSMs needed tangible measures, such as the introduction of new materials including masks and disinfectant, in order to recognize and then respond to the paradox. It is hardly surprising that this external stimulus was necessary since FLEs and FLSSMs in Austria, in contrast to Asian countries (Henderson & Ng, Citation2004), had no experience in dealing with infectious diseases. We developed to summarize in a process-orientated way the findings of our study on FLEs who learnt to strike a balance between maintaining business as usual and preparing for the uncertain in the midst of the winter season.

Figure 2. Crisis model based on Gioia et al. (Citation2013) and Ritchie (Citation2009).

Pre-crisis situation: While many tourism regions are experienced in managing natural disasters triggered by avalanches or floods (Mair et al., Citation2016), epidemics were unprecedented in Alpine tourism (Peters & Pikkemaat, Citation2005). It is therefore not surprising that crisis handling in tourist areas was strongly informed by disaster management practices aimed at evacuating tourists from risk areas. When in mid-March 2020 the COVID-19 shutdown and quarantine were imposed, many organizations were severely hit and ill-prepared, with few if any contingency plans.

Response & management: Strategic crisis responses such as retrenchment, persevering, innovation and exit are well documented (Wenzel et al., Citation2020). For the tourism industry, service hibernation is another potential strategy aiming to ‘scale back and/or shut down its service functions and operations during the COVID-19 pandemic’ (Tuzovic & Kabadayi, Citation2020, p. 3). Our findings reveal retrenchment activities such as ‘close and fire’, persevering to ‘continue operations’ with safety measures and ‘preparation and anticipation’ activities where firms manage their activities by introducing innovations to prepare for future waves of COVID-19 or react with a precautionary reduction of the workforce. Our findings show that hospitality organizations achieved only small-scale preparations for the COVID-19 shutdown, and that the threat was underestimated on both the regional and national levels, leaving plenty of room for various sense-giving attempts by tourism employees ().

Decomposing the narratives of our interviewees supports that ‘large crises [can be understood] as the outcome of smaller scale enactments’ (Weick, Citation1988, p. 314). Previous research has highlighted the role of routines for shifting responsibilities across various actors (Schad et al., Citation2016). Since high employee turnover (Yang et al., Citation2012) and a focus on day-to-day business is prevalent in tourism, extraordinary practices to cope with tensions arising from COVID-19 such as its outbreak were less structured and only loosely coupled with hospitality and tourism organizations. For example, managers decided to suddenly close operations without prior notice, with front-end employees having to extend their roles beyond the ordinary during the crisis (Johnston & Norris, Citation2020). From a practice-perspective view, the amount of normalization through stable routines is useful unless it deters from ‘remaining attentive to emerging events’ (Styhre, Citation2009, p. 386). Yet, defensive responses aiming at short-term relief often fail to embrace paradoxical poles (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013).

Focusing on extraordinary practices, we also supplement other studies on individuals’ everyday reactions (Wendy et al., Citation2017), confirming that humour, irony, and metaphors were essential aspects of sensemaking attempts during the crisis (Gylfe et al., Citation2020). In particular at the beginning of the crisis, when business still showed continuity (Tuzovic & Kabadayi, Citation2020), employees not only used humour and irony, but also collectively denied the threat, even while individual awareness about it started growing. This created ‘system contradictions’ (Lüscher et al., Citation2008), reinforcing the vicious circle of not preparing and responding in spite of the threat that was closing in. This is also supported by our findings on various sensemaking attempts, showing that along with ‘nothing to worry about’, employees also perceived that ‘something is coming’ and the need to ‘brace yourself’ (). Nevertheless, interviewees also described many situations illustrating the paradoxes they faced. This became visible by drawing on various resourcing practices such as situational reframing and organizational preframing (Schneider et al., Citation2020). Examples of the former included the calming of guests, reassuring them that everything was normal, even though employees did in fact sense rising tension, and provided disinfectant or changed their physical contact with guests.

Resolution and recovery: Following previous crisis- (Bhaskara & Filimonau, Citation2021) and non-crisis related (Lewis, Citation2000) literature on paradoxes of learning, we confirm that the more things change, the more they stay the same. Consistent with this, we expected that experiences during COVID-19 would shape how employees move on after the pandemic (Demirović Bajrami et al., Citation2020), while also finding that crisis-related incidents were not blamed for staff turnover on the micro level. From a cultural perspective on hospitality employment issues (Baum et al., Citation2016; Ladkin, Citation2011), neither organizational and industry attributes (e.g. long hours, lack of career prospects), nor personal employee dimensions (e.g. stress, burnout), nor job-induced work-life conflicts (Deery & Jago, Citation2015) affect staff turnover per se; it is rather the normalization of these practices and conditions that shape the dominant hospitality employment conditions (Johnson, Citation2020).

Implications for post-crisis situations: Interviewees were working towards the end of the season and looking forward to their farewell celebrations after an intense season. Nevertheless, the crisis suspended the usual ‘rules of the game’ of seasonal employment. In this context, previous literature emphasized the power of virtual breaks and happy hours to reduce tensions arising from a lack of socializing (Carnevale & Hatak, Citation2020). Our findings show a lack of communication and supervisory support for employees, thus far confirming previous research and highlighting the importance of securing employees’ wellbeing during a crisis (Dirani et al., Citation2011; Tuzovic & Kabadayi, Citation2020). For future employee retention, tourism organizations will need to show more leadership, including new formats of exchange and communication to alleviate the effects of social distancing in the workplace (Tuzovic & Kabadayi, Citation2020). This study provides a first assessment of the tensions that FLEs experienced during the first lockdown, however, more research on organizations addressing employees’ experiences and sensemaking during COVID-19 will be central to improving the understanding of and commitment to staff turnover issues, highlighting the role of ‘softer elements of HR such as communication, coaching and personal development’ for employee retention (D’’Annunzio-Green & Baum, Citation2008). Taking into consideration the various sensemaking approaches (), we agree that organizations need to rethink employee retention not only in times of crisis (Hughes & Rog, Citation2008).

6. Conclusions and recommendations

While the tourist perspective has to date dominated the discussion around COVID-19 recovery (Bausch et al., Citation2020), we explored the central role that FLEs play during crises given that the tourism industry is extremely dependent on well-trained and qualified employees in running their operations. This research highlighted the importance of developing human resource management strategies which might be able to mitigate or even avoid the impact of crises on FLEs (Ertaş et al., Citation2021). Therefore, this study showed how events gradually triggered employees’ sensemaking and interorganizational measures during the COVID-19 crisis in the tourism and hospitality industry. Understanding these experiences helps to improve the management of extraordinary tensions during crisis events. In particular, while the crisis was on the horizon (), FLEs were involved in various situated sensemaking and -giving processes, experiencing the absence of adequate preparations and leadership, while still maintaining operations by drawing on a unique set of resources embedded in the high service orientation of the industry. When the crisis finally hit and disrupted all functions to an unexpected degree (Laws & Prideaux, Citation2005), we found several incidents affecting employees’ everyday practices and resulting in extraordinary tensions. Enacting new routines and making sense of paradoxical situations (Smith & Lewis, Citation2011) was also supported by the resources and mechanisms built into the business model such as balancing between efficiency and customer orientation and the industry’s experience in ‘hibernation’ ().

Taking into consideration employees’ sensemaking, existing resources, and paradoxes, we highlight several managerial implications which provide guidelines for the future management of extraordinary situations whilst also informing HR practices for FLEs facing everyday tensions.

First, employees had various roles and responsibilities (Johnston & Norris, Citation2020) and engaged in various ways in resourcing and sensemaking/-giving, which did not always achieve an environment of ‘unexpected simultaneous failure’ (Weick, Citation1988). To secure employee retention after a crisis, organizations need to contact and engage with their employees to show how much they valued their commitment and contributions during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, virtual meetings offer the opportunity to talk to employees in one-to-one settings and to enable virtual lunches and breaks in social-distancing situations (Carnevale & Hatak, Citation2020). Another opportunity to enter into communication with employees emerges from equipment and personal belongings that had to be left behind due to the rapid evacuation. The overall goal of these HR practices should be to improve resilience, secure the employer-employee fit (Carnevale & Hatak, Citation2020) and prevent decreasing workplace satisfaction and morale (Lo et al., Citation2006).

Second, the crisis highlighted employee-specific capabilities and strengths which opens up new possibilities for organizations and employees to reflect upon the process of co-creation, and perhaps even to establish new responsibilities (Martins et al., Citation2020). FLEs were particularly hard hit by the hibernation mode that many organizations entered, Thus, to sustain talented employees in times of reduced employment, talent pools and sharing employees with other service sectors could be a solution (Martins et al., Citation2020). Organizations should, however, maintain their efforts to secure employees since Baum et al. (Citation2020, p. 2822) reported that ‘sharing labour pools may be a double-edge sword in the future war for talent as hospitality workers fail to return to their sector of origin’.

Third, many seasonal employees were surprised by the sudden employee exodus and received little information about it. As a lesson learned from the COVID-19 crisis, we suggest the development of destination and organization-wide crisis contingency plans which not only target customers, but also employees as important stakeholders. The interviews made clear that communication bottlenecked during the crisis. There was no coherent flow of information between institutions or organizations, and information was even contradictory. Eliminating these asymmetries will not only benefit organizations but help employee retention as well. As indicated in recent studies ‘managers should therefore initiate two-way communication with the staff to gain a full understanding of employee concerns’ (Choy & Kamoche, Citation2021, p. 1385), especially in times of uncertainty.

This study is also subject to limitations emerging from its qualitative nature and regional context, hindering generalizability. Specifically, sensemaking as a concept where researchers aim ‘to make sense of how others make sense’ while casting aside previous knowledge (Parry, Citation2003, p. 255) undoubtedly has its limitations. Other limitations include the unexpected challenges of sampling and interviewing seasonal workers who often had second thoughts and dropped out of the study. Additionally, this study was only able to cover the developments around the first lockdown. There exist several recommendations for future research. First, it would be worth exploring the development of employee retention and employees’ attitudes towards their employers. Second, future research should also examine the everyday tensions and paradoxes between regular staff and seasonal employees from different cultural backgrounds in the tourism and hospitality industry. Lastly, future research could explore additional layers of complexity such as paradoxical tensions between long-term and short-term needs (Collings et al., Citation2021).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Tobias Krall forthe support in the initial phase of the project and Isabelle Esser for her proofreading of the main text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aliperti, G., Sandholz, S., Hagenlocher, M., Rizzi, F., Frey, M., & Garschagen, M. (2019). Tourism, crisis, disaster: An interdisciplinary approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 102808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102808

- AMS. (2021). Arbeitsmarkt: Daten, Forschung sowie Medieninformation. https://www.ams.at/regionen/osterreichweit/news/2020/06/ende-mai-waren-517-221-personen-auf-jobsuche-oder-in-schulung

- Bartik, A., Bertrand, M., Cullen, Z., Glaeser, E., Luca, M., & Stanton, C. (2020). How are small businesses adjusting to COVID-19? Early evidence from a survey. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26989

- Baum, T., Kralj, A., Robinson, R. N., & Solnet, D. J. (2016). Tourism workforce research: A review, taxonomy and agenda. Annals of Tourism Research, 60, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.04.003

- Baum, T., Mooney, S. K., Robinson, R. N., & Solnet, D. (2020). COVID-19’s impact on the hospitality workforce – new crisis or amplification of the norm? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(9), 2813–2829. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2020-0314

- Bausch, T., Gartner, W. C., & Ortanderl, F. (2020). How to avoid a COVID-19 research paper tsunami? A tourism system approach. Journal of Travel Research, 60(3), 467–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520972805 .

- Bean, C. J., & Eisenberg, E. M. (2006). Employee sensemaking in the transition to nomadic work. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 19(2), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810610648915

- Bhaskara, G. I., & Filimonau, V. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and organisational learning for disaster planning and management. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 46, 364–375. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.01.011

- Bolton, S. C., & Houlihan, M. (2010). Bermuda revisited? Work and Occupations, 37(3), 378–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888410375678

- Carmine, S., Andriopoulos, C., Gotsi, M., Härtel, C. E. J., Krzeminska, A., Mafico, N., Pradies, C., Raza, H., Raza-Ullah, T., Schrage, S., Sharma, G., Slawinski, N., Stadtler, L., Tunarosa, A., Winther-Hansen, C., & Keller, J. (2021). A paradox approach to organizational tensions during the pandemic crisis. Journal of Management Inquiry, 30(2), 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492620986863

- Carnevale, J. B., & Hatak, I. (2020). Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research, 116, 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037

- Chi, X., Cai, G., & Han, H. (2021). Festival travellers’ pro-social and protective behaviours against COVID-19 in the time of pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1908968

- Choy, M. W., & Kamoche, K. (2021). Identifying stabilizing and destabilizing factors of job change: A qualitative study of employee retention in the Hong Kong travel agency industry. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(10), 1375–1388. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1792853

- Collings, D. G., Nyberg, A. J., Wright, P. M., & McMackin, J. (2021). Leading through paradox in a COVID-19 world: Human resources comes of age. Human Resource Management Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12343

- D’Annunzio-Green, N., & Baum, T. (2008). Implications of hospitality and tourism labour markets for talent management strategies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(7), 720–729. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110810897574

- Deery, M. A., & Jago, L. (2015). Revisiting talent management, work-life balance and retention strategies. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(3), 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2013-0538

- Demirović Bajrami, D., Terzić, A., Petrović, M. D., Radovanović, M., Tretiakova, T. N., & Hadoud, A. (2020). Will we have the same employees in hospitality after all? The impact of COVID-19 on employees’ work attitudes and turnover intentions. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94 102754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102754.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. (2011). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 1–19). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Dirani, K. M., Abadi, M., Alizadeh, A., Barhate, B., Garza, R. C., Gunasekara, N., Ibrahim, G., & Majzun, Z. (2020). Leadership competencies and the essential role of human resource development in times of crisis: A response to covid-19 pandemic. Human Resource Development International, 23(4), 380–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2020.1780078

- Ertaş, M., Sel, Z. G., Kırlar-Can, B., & Tütüncü, Ö. (2021). Effects of crisis on crisis management practices: A case from turkish tourism enterprises. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(9), 1490–1507. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1879818

- Falk, M., & Hagsten, E. (2020). The unwanted free rider: Covid-19. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(19), 2693–2698. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1769575.

- Faulkner, B. (2001). Towards a framework for tourism disaster management. Tourism Management, 22(2), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00048-0

- Flyvberg, B. (2011). Case study. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 301–316). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Fuchs, M., & Weiermair, K. (2001). Development opportunities for a tourism benchmarking tool: The case of tyrol. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 2(3-4), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1300/J162v02n03_05

- Gabriel, Y. (2009). Latte capitalism and late capitalism: Reflections on fantasy and care as part of the service triangle. In M. Korczynski (Ed.), Service work: Critical perspectives (pp. 175–189). Routledge.

- Gherardi, S. (2009). Knowing and learning in practice-based studies: An introduction. The Learning Organization, 16(5), 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470910974144

- Gioia, D. A., & Chittipeddi, K. (1991). Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change intitiation. Strategic Management Journal, 12(6), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120604

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research (4th ed.). Aldine.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708.

- Gylfe, P., Franck, H., & Vaara, E. (2019). Living with paradox through irony. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 155, 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2019.03.002

- Helpap, S., & Bekmeier-Feuerhahn, S. (2016). Employees’ emotions in change: Advancing the sensemaking approach. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 29(6), 903–916. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-05-2016-0088

- Henderson, J. C., & Ng, A. (2004). Responding to crisis: Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and hotels in Singapore. International Journal of Tourism Research, 6(6), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.505

- Herbane, B. (2010). Small business research: Time for a crisis-based view. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 28(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242609350804

- Hughes, J. C., & Rog, E. (2008). Talent management. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 20(7), 743–757. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110810899086

- Independent Commission of Experts. (2020). Management COVID-19-pandemie tirol. https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/presse/downloads/Presse/Bericht_der_Unabhaengigen_Expertenkommission.pdf

- Jarzabkowski, P., Lê, J. K., & van de Ven, A. H. (2013). Responding to competing strategic demands: How organizing, belonging, and performing paradoxes coevolve. Strategic Organization, 11(3), 245–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127013481016

- Jarzabkowski, P. A., & Lê, J. K. (2017). We have to do this and that? You must be joking: Constructing and responding to paradox through humor. Organization Studies, 38(3-4), 433–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616640846

- Jay, J. (2013). Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. The Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 137–159. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0772

- Johnson, A.-G. (2020). We are not yet done exploring the hospitality workforce. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 86, 102402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102402

- Johnston, D. M., & Norris, J. R. (1989). Role extension in disaster: Employee behavior at the beverly hills supper club fire. Sociological Focus, 22(1), 39–51.

- Karatepe, O. M., Saydam, M. B., & Okumus, F. (2021). COVID-19, mental health problems, and their detrimental effects on hotel employees’ propensity to be late for work, absenteeism, and life satisfaction. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(7), 934–951. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1884665

- Keyser, B., Guiette, A., & Vandenbempt, K. (2019). On the use of paradox for generating theoretical contributions in management and organization research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 21(2), 143–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12201

- Ladkin, A. (2011). Exploring tourism labor. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(3), 1135–1155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.010

- Land Tirol. (2020). Gesetz vom 8. Februar 2006 über das Katastrophenmanagement in Tirol (Tiroler Katastrophenmanagementgesetz). https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/GeltendeFassung.wxe?Abfrage=LrT&Gesetzesnummer=20000180

- Laws, E., & Prideaux, B. (2005). Crisis management: A suggested typology. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 19(2-3), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v19n02_01

- Lewis, M. W. (2000). Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 760–776. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.3707712

- Lindberg, O., Rantatalo, O., & Hällgren, M. (2017). Making sense through false syntheses: Working with paradoxes in the reorganization of the Swedish police. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 33(3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2017.06.003

- Lo, A., Cheung, C., & Law, R. (2006). The survival of hotels during disaster: A case study of Hong Kong in 2003. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 11(1), 65–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941660500500733

- Lundberg, C. C., & Young, C. A. (1997). Newcomer socialization: Critical incidents in hospitality organizations. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 21(2), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/109634809702100205

- Lüscher, L. S., & Lewis, M. W. (2008). Organizational change and managerial sensemaking: Working through paradox. The Academy of Management Journal, 51(2), 221–240. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.5465/AMJ.2008.31767217

- Lüscher, L. S., Lewis, M. W., & Ingram, A. (2006). The social construction of organizational change paradoxes. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 19(4), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810610676680

- Mair, J., Ritchie, B. W., & Walters, G. (2016). Towards a research agenda for post-disaster and post-crisis recovery strategies for tourist destinations: A narrative review. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2014.932758

- Maitlis, S., & Christianson, M. (2014). Sensemaking in organizations: Taking stock and moving forward. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 57–125. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2014.873177

- Maitlis, S., & Sonenshein, S. (2010). Sensemaking in crisis and change: Inspiration and insights from Weick (1988). Journal of Management Studies, 47(3), 551–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00908.x

- Martins, A., Riordan, T., & Dolnicar, S. (2020). A post-COVID-19 model of tourism and hospitality workforce resilience. SocArXiv, Preprint. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/4quga

- Mayer, M., Bichler, F. B., Pikkemaat, B., & Peters, M. (2021). Media discourses about a superspreader destination: How mismanagement of Covid-19 triggers debates about sustainability and geopolitics. Annals of Tourism Research, 91, 103278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103278

- Mejia, C., Pittman, R., Beltramo, J. M., Horan, K., Grinley, A., & Shoss, M. K. (2021). Stigma & dirty work: In-group and out-group perceptions of essential service workers during COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 93, 102772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102772

- Ngoc Su, D., Luc Tra, D., Thi Huynh, H. M., Nguyen, H. H. T., & O’Mahony, B. (2021). Enhancing resilience in the Covid-19 crisis: Lessons from human resource management practices in Vietnam. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1863930

- Park, E., Kim, W.-H., & Kim, S.-B. (2020). Tracking tourism and hospitality employees’ real-time perceptions and emotions in an online community during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1823336

- Parry, J. (2003). Making sense of executive sensemaking. A phenomenological case study with methodological criticism. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 17(4), 240–263. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777260310494771

- Peters, M., & Pikkemaat, B. (2005). Crisis management in alpine winter sports resorts: The 1999 avalanche disaster in Tyrol. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 19(2-3), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v19n02_02

- Pradies, C., Aust, I., Bednarek, R., Brandl, J., Carmine, S., Cheal, J., Pina e Cunha, M., Gaim, M., Keegan, A., Lê, J. K., Miron-Spektor, E., Nielsen, R. K., Pouthier, V., Sharma, G., Sparr, J. L., Vince, R., & Keller, J. (2021). The lived experience of paradox: How individuals navigate tensions during the pandemic crisis. Journal of Management Inquiry, 30(2), 154–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492620986874

- Ritchie, B. W. (2009). Crisis and disaster management for tourism. Channel View Publications.

- Rouleau, L. (2005). Micro-practices of strategic sensemaking and sensegiving: How middle managers interpret and sell change every day. Journal of Management Studies, 42(7), 1413–1441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00549.x

- Schad, J., Lewis, M. W., Raisch, S., & Smith, W. K. (2016). Paradox research in management science: Looking back to move forward. Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 5–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2016.1162422

- Schneider, A., Bullinger, B., & Brandl, J. (2021). Resourcing under tensions: How frontline employees create resources to balance paradoxical tensions. Organization Studies, 42(8), 1291–1317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620926825.

- Schneider, A., Subramanian, D., Suquet, J.-B., & Ughetto, P. (2021). Situating service work in action: A review and a pragmatist agenda for analysing interactive service work. International Journal of Management Reviews, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12259.

- Sigala, M. (2020). Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 312–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.015

- Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 381–403. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0223

- Sparr, J. L. (2018). Paradoxes in organizational change: The crucial role of leaders’ sensegiving. Journal of Change Management, 18(2), 162–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2018.1446696

- Steigenberger, N. (2015). Emotions in sensemaking: A change management perspective. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 28(3), 432–451. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-05-2014-0095.

- Stergiou, D. P., & Farmaki, A. (2021). Ability and willingness to work during COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives of front-line hotel employees. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 93, 102770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102770

- Stoker, J. I., Garretsen, H., & Soudis, D. (2019). Tightening the leash after a threat: A multi-level event study on leadership behavior following the financial crisis. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2018.08.004

- Styhre, A. (2009). Tinkering with material resources. The Learning Organization, 16(5), 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1108/09696470910974171

- Sutherland, F., & Smith, A. C. T. (2011). Duality theory and the management of the change–stability paradox. Journal of Management & Organization, 17(4), 534–547. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1833367200001437

- Tirol Werbung. (2019). Tyrol’s tourism at a glance. https://www.tirolwerbung.at/tiroler-tourismus/zahlen-und-fakten-zum-tiroler-tourismus/

- Tsoukas, H., & Chia, R. (2002). On organizational becoming: Rethinking organizational change. Organization Science, 13(5), 567–599. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.5.567.7810

- Tuckermann, H. (2018). Visibilizing and invisibilizing paradox: A process study of interactions in a hospital executive board. Organization Studies, 40(12), 1851–1872. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618800100

- Tuzovic, S., & Kabadayi, S. (2020). The influence of social distancing on employee well-being: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 32(2), 145–160. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0140.

- Vo-Thanh, T., Vu, T.-V., Nguyen, N. P., van Nguyen, D., Zaman, M., & Chi, H. (2021). COVID-19, frontline hotel employees’ perceived job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: Does trade union support matter? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1910829

- Vuori, J. (2013). A foresight process as an institutional sensemaking tool. Education + Training, 57(1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2013-0090

- Weick, K. E. (1988). Enacted sensemaking in crisis situations. Journal of Management Studies, 25(4), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1988.tb00039.x

- Weick, K. E. (2001). Making sense of the organization: The impermanent organization. Making sense of the organization. Wiley.

- Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0133

- Wendy, S. K., Lewis, M. W., Jarzabkowski, P., & Langley, A. (2017). The Oxford handbook of organizational research. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198754428.013.24

- Wenzel, M., Stanske, S., & Lieberman, M. B. (2020). Strategic responses to crisis. Strategic Management Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3161

- Yang, J.-T., Wan, C.-S., & Fu, Y.-J. (2012). Qualitative examination of employee turnover and retention strategies in international tourist hotels in Taiwan. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(3), 837–848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.10.001