ABSTRACT

This study unpacks how a person’s multiple identities affect their decision making when selecting a tourism destination. We propose that different aspects of identity yield distinct yet competing emotions. For instance, perceived social audience admiration combined with animosity might produce ambivalence, leading to greater decision-making uncertainty. Findings show that tourists with greater ambivalence towards particular destination countries are more likely to cancel or postpone their travel decisions. Additionally, the destination country’s economic development and a tourist’s pursuit of material happiness interact as moderators in the relationships between identities, emotions, and travel intention. Recommendations are provided for tourism product development and marketing communications for destination countries.

Introduction

International tourism is facing unprecedented challenges. Growing anti-globalization movements; geopolitical tensions; and national, regional, and ethnic group inequalities have compelled people to review their ideologies, personal values, and group identities. When a Singaporean student was brutally attacked by a group of men in London, England, in March 2020 (BBC, Citation2020), the news went viral on social media and sparked anxiety among Asians regarding potential on-site animosity and personal safety when travelling. Unger et al. (Citation2021) also noted this phenomenon among Israeli business travellers who adopted different coping strategies to mitigate on-site animosity around their national identity when visiting certain countries. These instances exemplify the linkages between social identity, emotions, and behaviour.

Tourism studies involving social identity have focused on several topics: identity congruence between a place and its tourists (Palmer, Citation2005); heritage tourism that reflects national, religious, and cultural identities (Gieling & Ong, Citation2016); and the symbolism of social identity and international tourism (Desforges, Citation2000; Yang et al., Citation2020). Researchers have also considered how residents’ social identity aligns with their support of local tourism and their interactions with inbound tourists (Ballesteros & Ramìrez, Citation2007; Moufakkir, Citation2014; Palmer et al., Citation2013). Yet investigations of how people experience, perform, and negotiate their multiple identities in international tourism are scarce. In this context, one’s group identity (e.g. national, religious, or cultural) is likely to be triggered by direct interaction between their in-group and out-group (Unger et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2019). Apart from experiencing multiple identities in a destination, one’s identity also comes into play prior to tourism consumption (e.g. throughout the planning process) (Gieling & Ong, Citation2016).

Social identity theory asserts that people ascribe different identities to convey who they are and to communicate the groups to which they belong in certain situations (Palmer, Citation1999; Stets & Burke, Citation2000). In tourism, visiting specific places can ‘be conceived as a means of establishing, maintaining and at times recreating aspects of one’s identity and that all tourist experiences are to a certain extent motivated by the individual’s self-perceived identity-related needs’ (Bond & Falk, Citation2013, p. 439). A person may intend to present a particular image, demonstrate their desired identity to others, or showcase their belongings to their social group via tourism consumption (Gieling & Ong, Citation2016).

The existence of multiple identities can lead to complex emotions and nuanced behavioural involvement, which may generate decision-making ambivalence depending on a person’s immediate context and past experiences (Gieling & Ong, Citation2016; Palmer, Citation1999). Ambivalence, as applied to consumer behaviour, refers to ‘the simultaneous or sequential experience of multiple emotional states, as a result of the interaction between internal factors and external objects … that can have direct and/or indirect ramifications on prepurchase, purchase or postpurchase attitudes and behaviour’ (Otnes et al., Citation1997, pp. 82–83). Research on ambivalence in consumer behaviour has increased since the 1990s. Tourism studies on the topic remain rare, with Kim and Um (Citation2016) and Chen et al. (Citation2019) being two notable exceptions.

In response to social developments and a paucity of academic work regarding multiple identities and decision-making ambivalence in tourism consumption, this study explores the following questions: a) How do multiple identities generate different emotions related to one’s intentions to visit a tourist destination?; and b) To what extent can ambivalence influence a tourist’s visit intentions? This study also examines how a destination country’s economic development and a traveller’s pursuit of materialism moderate these relationships.

This research contributes to relevant knowledge in three ways. First, findings broaden the understanding of social identity theory and delineate the effects of multiple identities on tourists’ emotions and consumption choices. Second, rather than investigating polarized positive versus negative emotions or using a traditional unidimensional like–dislike scale to measure ambivalence, we considered multifaceted emotions which are rooted in identities. Finally, by exploring the role of ambivalence in individuals’ decision making when choosing a tourism product (destination) and by considering the intricacies of conflicting identities that produce ambivalence, our results will help tourism marketers better understand inbound visitors. These findings further inform recommendations for tourism product development and marketing communications among tourism destination stakeholders.

Theoretical background

Multiple identities and co-existing emotions

Social identity reflects one’s ‘ … knowledge that he belongs to certain social groups together with some emotional and value significance to him of this group membership’ (Tajfel, Citation1972, p. 292). A person’s social identity comprises multiple forms of membership, such as nationality, culture, religion, gender, and ethnicity (Hogg et al., Citation1995). Although people can not choose the social groups into which they are born, they undergo dynamic identity development influenced by personal and group traits under varied circumstances (Gieling & Ong, Citation2016; Markus & Kitayama, Citation1991).

Individuals activate different aspects of their social identities in response to social contexts and environmental cues through self-categorization. This classification can either be on a distinct individual basis (i.e. independent self-construal) or group-oriented (i.e. interdependent self-construal) and is situational (Agrawal & Maheswaran, Citation2005). The social categorization process leads people to engage in corresponding social actions that define their positions in society. When individuals assign themselves to a social group which they believe best represents them, they are more likely to adopt traits and values stereotypical for that group (Chattaraman et al., Citation2010; Gieling & Ong, Citation2016). Intergroup categorization in turn sparks in-group favouritism and out-group discrimination (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1987).

People evaluate their social groups via comparison. Individuals’ perceptions of their social identities can be positive or negative upon comparing themselves with other group members (i.e. intragroup comparison) or upon comparing in-group and out-group members (i.e. intergroup comparison) (Hogg, Citation2000; Wang et al., Citation2019). People typically deem themselves to be worse or better than others. These appraisals can evoke myriad reactions, both optimistic (e.g. admiration and inspiration) and pessimistic (e.g. shame, resentment, or envy) (Smith, Citation2000).

Social identity and social comparison have been used to explain consumer behaviour, as people’s consumption habits tend to reinforce or distinguish their positions in groups within certain contexts. Such social categorization and comparison can then trigger intergroup discrimination, prejudice, and antagonism towards out-groups—namely through expressing pride in or favour for one’s in-group. Social psychology and behaviour are also closely associated with the interpersonal–intergroup continuum (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1987). For example, to acquire or maintain a high social status, consumers frequently engage in costly behaviour (i.e. procuring, using, and displaying products and services) to present a favourable image to a social audience (Chugani & Irwin, Citation2020; Ivanic, Citation2015) and to attain interpersonal psychological benefits (i.e. an enhanced sense of self and a feeling of prestige). This identity-signalling behaviour often generates positive feelings, as people feel they are respected and admired (Gal, Citation2015).

Consuming tourism products is akin to conspicuous consumption in terms of the symbolic values that people use to display their superiority to a social audience (Correia et al., Citation2020; MacCannell, Citation1976). People enjoy visiting places with prestigious attributes (e.g. distinctiveness, uniqueness, and worldwide recognition) to reflect life achievements and garner admiration. For instance, Correia et al. (Citation2016) used an interview approach to explore how elite Portuguese tourists constructed meanings of tourism as a form of conspicuous consumption to match their personal identities.

In addition to interpersonal relationships, the concept of social identity stresses intergroup relations. People interact with others as members of differentiated groups, such as racial groups, religious groups, or nation-states (Bar-Tal & Avrahamzon, Citation2017). A strong connection to a particular group affords individuals ‘strength and a sense of identity’ (Kelman, Citation1961, p. 64). When confronted with conflicting group interests, people are apt to bolster their identification with the in-group and exhibit antagonistic attitudes towards an out-group. The search for a positive group identity invigorates this comparison process and elicits strong ethnocentrism and antagonism towards an out-group (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1987).

To evaluate their in-group positively, individuals usually accentuate group members’ distinctive and affirmative aspects. Downward comparison (on the basis of power, prestige, or wealth) with out-group members provides in-group members a sense of pride and compels them to hold prejudiced and stereotypical perceptions of an out-group (Unger et al., Citation2021). Prejudice is grounded in group identification via categorization and comparison. National prejudice starts with self-categorization: one’s sense of belongingness to a particular nation generates a self-stereotype by comparing one’s home nation with other nations (Rutlad, Citation1999). The development of prejudice against racial or ethnic groups begins as early as age 6 (Bar-Tal & Teichman, Citation2005). People expressing prejudice generally believe that their in-group is superior to an out-group. Prejudice also manifests in group-based emotions like hate, animosity, and perceptions of threat or sympathy among societal members (Bar-Tal & Avrahamzon, Citation2017).

Animosity—a collective memory and ethos of conflict igniting hostile intergroup rivalry—generates strong feelings of in-group membership, shared identity, solidarity, and cohesiveness (Klein et al., Citation1998). Tourism research has revealed a negative relationship between animosity and one’s intention to visit a destination. This outcome is plausible, as group identity requires people to seek group acceptance and to comply with group behaviour (Alvarez & Campo, Citation2020). Moufakkir (Citation2014) examined how people with different political identifications evaluated Moroccan immigrants and how immigrant-associated animosity could weaken visit intentions. Abraham and Poria (Citation2020) found that animosity due to tourists’ political identification could lead to more negative tourism-related behaviour.

Ambivalence, intention, and behaviour

Ambivalence refers to ‘a psychological state in which a person holds mixed feelings (positive and negative) towards some psychological object’ (Gardner, Citation1987, p. 241). People feel ambivalent when they have competing emotions towards an attitudinal object (Thompson et al., Citation1995). For example, the prospect of a ghost-hunting trip can be both exciting and terrifying. When the anticipated excitement and terror hold the same weight and compete as strong co-existing emotions, people may become ambivalent in their decisions.

Because indecisiveness causes discomfort, people are likely to deploy coping strategies to reduce dissonance (Randers et al., Citation2021). Scholars have uncovered multiple patterns in the relationship between ambivalence and behaviour. Sparks et al. (Citation2001) observed a significant and negative relationship between individuals’ ambivalence and attitudes towards meat consumption, but the relationship was not significant regarding chocolate consumption. Olsen et al. (Citation2005) noted that the extant literature had mostly documented a negative or non-significant relationship between ambivalence and behavioural intention.

In tourism, Kim and Um (Citation2016) explored how ambivalence influences people’s behavioural intentions in medical tourism and identified the critical role of ambivalence in tourists’ decision making. Chen et al. (Citation2019) measured residents’ attitudinal ambivalence towards supporting tourism development or mega-events, taking the 2010 Shanghai Expo as an empirical case. Findings demonstrated the role of attitudinal ambivalence in predicting residents’ behaviour; the authors argued that ambivalence towards an object can be changed if managed well. However, neither of these studies considered ambivalence affiliated with multiple identities and competing emotions. We accordingly theorize that the existence of multiple identities leads individuals to become ambivalent towards a consumption choice, which may have inconsistent or even conflicting psychological effects.

Hypothesis development

From identities to emotions

Social identity, or one’s identification with a social group(s), can involve three dimensions: cognitive, evaluative, and emotional (Palmer et al., Citation2013). The cognitive aspect of social identity facilitates one’s awareness of their membership in different social groups. The cognitive social group identification process is complicated; people classify groups situationally (Hogg & Terry, Citation2000). The evaluative aspect of social identity relates to negative or positive intergroup comparison. The results of this comparison may lead to either high or low self-esteem depending on how individuals perceive out-groups. Inferior groups have been shown to display positive attitudes towards superior groups or intensified antagonism towards privileged groups (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1987). Social identity can also be emotion-based: people may identify with a particular group without affectively committing to that group (Palmer et al., Citation2013).

Tourism researchers have additionally scrutinized the relationships between social identity and its impacts on tourism-related behaviour. Many people use tourism product consumption to highlight their social status, which leads to positive emotions (Correia & Moital, Citation2009). On the contrary, identifying with a social group may generate negative emotions when visiting places where locals express hostility towards that group (Unger et al., Citation2021). This study adopted individual material success as a reflection of personal identity and prejudice against a destination country as a way to strengthen group identity.

Materialism captures one’s value orientation towards the importance of acquiring and possessing objects. These items are frequently used to validate personal success, a desired self-image, and social status (Ivanic, Citation2015; Richins & Dawson, Citation1992). People who believe in material success are more likely to consume high-status, luxury brands and products that can evoke admiration from others. Approval from a social audience elicits heightened feelings of prestige, self-esteem, and the enjoyment of self-verification (Ivanic, Citation2015).

Tourism is a leisure product, particularly international travel, and requires substantial investments in time and money. The uniqueness of a travel experience is largely attributable to high prices and scarcity (Vigneron & Johnson, Citation1999). Travelling to an exotic place can portray one’s social status and material success. As Correia and Moital (Citation2009) remarked, ‘ … individuals strive to improve their regard or honour through the consumption of tourism experiences that confer and symbolize the prestige both for individuals and surrounding others’ (p. 18). We therefore hypothesize the following:

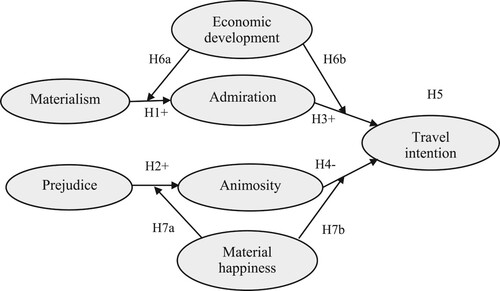

H1: A significant positive relationship exists between materialism and perceived social audience admiration when visiting a particular destination.

Prejudice is inherent in international tourism due to intergroup relations. People who hold a strong prejudice towards an out-group may want to confirm their in-group membership by avoiding places and tourism products that oppose in-group values (Correia et al., Citation2016). They instead opt to visit places that most in-group members accept. If people from a given source market hold a substantial prejudice against a destination country with a history of conflict against the source market, they will likely feel strong animosity towards that destination (Alvarez & Campo, Citation2020). The following hypothesis is proposed accordingly:

H2: A significant positive relationship exists between prejudice and animosity towards a destination country.

Emotions, ambivalence, and travel intention

Individuals are more likely to engage in consumption behaviour of which their perceived social audience will approve. Consumers enjoy receiving positive feedback about their product choices and may spend time imagining potential admiration (Chugani & Irwin, Citation2020). This phenomenon is prevalent among materialists who seek self-satisfaction by engaging in prestige consumption to demonstrate their high status. To uphold their ideal self-image, materialists are likely to pursue social audience admiration through international tourism or by travelling to exotic or expensive destinations (Jang & Wu, Citation2006). Stated formally:

H3: Perceived social audience admiration has a significant positive impact on one’s intentions to visit a destination.

People engage in certain behaviours to affiliate with in-group members while differentiating themselves from out-groups (Stets & Burke, Citation2000). Animosity, which includes cynical cognitive beliefs and mistrust of a perceived out-group based on previous or ongoing events, normally embodies negative feelings towards an out-group (Little & Singh, Citation2014). Multiple factors contribute to animosity; however, it is often reflected in consumer behaviour as the rejection of products from a rival entity (Ouellet, Citation2007). Tourism research suggests that people feeling animosity towards a destination country are less likely to visit it (Campo & Alvarez, Citation2017). As such, we propose that:

H4: Animosity towards a destination country has a significant negative impact on one’s intentions to visit a destination.

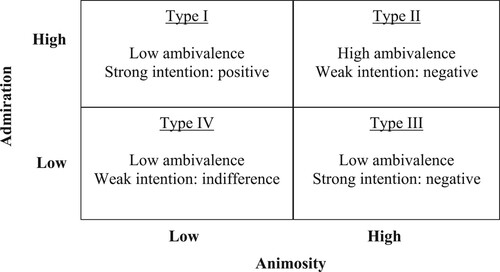

Scholars have argued that ambivalence can result in two representative attitudes, namely strong and weak (Olsen et al., Citation2005). When people hold either mostly positive or mostly negative attitudes towards an object, they tend to exhibit low ambivalence. Type I and Type III in depict a tourist’s low ambivalence towards a destination country. Type I shows that a tourist feels less animosity towards the destination but expects to be highly admired by others for visiting it; Type III indicates a tourist’s high animosity towards the destination while not expecting to be admired for travelling there.

If people simultaneously hold strong positive and negative feelings towards a destination, they have high ambivalence (Onwezen et al., Citation2017). High ambivalence is generally adversely related to behavioural intention; people dislike dissonance (Proulx et al., Citation2012). To avoid dissonance, people may delay a decision or avoid it altogether (Harreveld et al., Citation2015). A tourist who expects admiration from others for visiting a destination but feels high animosity towards the place may display lower visit intentions (Type II in ). Type IV in features low ambivalence, as both emotions are weak. In contrast to the low behavioural intention caused by high ambivalence, the behavioural intention associated with Type IV is low due to decision-related indifference (Chen et al., Citation2019). In effect:

H5: Different degrees of ambivalence (high animosity + high admiration, low animosity + low admiration, high animosity + low admiration, and low animosity + high admiration) will lead to significant differences in tourists’ intentions to visit a specific country.

Destination country’s economic development and material happiness as moderators

A country’s image is a multidimensional construct that includes economic development.

A country’s level of economic development (i.e. developing vs. developed) influences consumption choices (Campo & Alvarez, Citation2014), perhaps because people want to affiliate themselves with attractive and/or strong social groups (Fisher & Wakefield, Citation1998). Moreover, people from developing countries tend to perceive prominent international brands from developed countries as high-quality status symbols (Guo, Citation2013). A similar phenomenon holds in tourism: Alvarez and Campo (Citation2014) found that a country’s extent of development significantly influences individuals’ visit intentions.

Travelling to developed countries normally carries higher costs and stricter visa screenings for visitors from developing countries (Czaika & Neumayer, Citation2017). These obstacles imply a scarcity of tourism products and render such countries exotic for mass consumers in developing countries. Hence, we presume that people who place more importance on material happiness perceive higher social audience admiration when they visit these places and thus have stronger intentions to travel to developed countries. We postulate that:

H6: A destination country’s economic development strengthens the relationship between (a) one’s pursuit of material happiness and perceived social audience admiration; and (b) perceived social audience admiration and travel intentions.

H7: One’s pursuit of material happiness strengthens the effects of (a) national prejudice and animosity towards the destination country/region and (b) animosity and travel intentions towards the destination country/region.

illustrates these hypotheses.

Methods

Research context

China’s rapid economic growth since the 1990s has fuelled expansion in domestic and international tourism consumption (Dai et al., Citation2017). The country has been a key source of international tourism in the last decade (Blackhall, Citation2019). Chinese tourists spent $258 billion on international tourism in 2017, representing one-fifth of the world’s total tourism spending (ChinaDaily, Citation2018) and indicating a substantial outbound travel market. Travelling internationally is a symbolic and prestigious form of consumption for many Chinese. As obtaining material success and surpassing others are considered achievements in traditional Chinese society (Li, Citation2016; Liao & Wang, Citation2017), people who can afford to visit destinations that others cannot tend to possess a sense of superiority. Materialism is also positively correlated with most values in collectivist societies (Awanis et al., Citation2017). At the same time, members of collectivist cultures are more likely to engage in consumption that reflects associated values to conform to a broader group (Triandis et al., Citation1990). China’s strong collectivist culture can compel citizens to show affiliation towards a group identity and to behave uniformly towards out-group members in specific situations (Hofstede, Citation2007; Yu et al., Citation2019).

Measures and destination selection

A survey was designed for this study to examine Chinese tourists’ intentions to visit destination countries. Travel intention was measured using three items adapted from Sánchez et al. (Citation2018), reflecting one’s likelihood of visiting a destination. Perceived social audience admiration was evaluated based on items from Blank et al. (Citation2018); respondents indicated their expectations of being admired by others if they travelled to a given destination country. Scales to measure animosity were taken from Klein et al. (Citation1998) and captured respondents’ overall dislike of a destination country. Prejudice was assessed with three items adapted from Choma et al. (Citation2018) to indicate respondents’ attitudes towards a destination country when comparing it with their own country. Finally, each destination country’s economic development was measured by GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP) in 2018. Items on materialism and material happiness were adapted from Richins and Dawson (Citation1992). All items were scored on a 7-point Likert scale anchored by 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. contains the measurement items.

Table 1. Results: Measurement items, reflective constructs, outer-loading and AVE.

To identify respondents’ competing emotions without arousing an internal attitudinal debate, this study employed a quasi-experimental research design to detect ambivalence by asking respondents to report respective evaluations of emotions (i.e. admiration + animosity). It was deemed necessary to identify four destination countries through a 2 (animosity: high vs. low) × 2 (economic development level: higher vs. lower than China) design to determine respondents’ ambivalence. We first listed 10 destination countries within a 6-hour flight from Shanghai, China, to ensure the destinations were close enough so that respondents would not be deterred by distance (Yang et al., Citation2018). Twenty-eight respondents were recruited in the summer of 2018 to report their animosity towards these locations (1 = most like, 10 = most dislike). Four destination countries were selected based on the ranking of favourability and each country’s GDP at PPP: Australia, South Korea, Vietnam, and Thailand. Australia and South Korea were categorized as having better economic development (with a higher GDP at PPP than China in 2018), and Vietnam and Thailand (each with a lower GDP at PPP) were classified as less economically developed (World Bank, Citation2019). Paired samples t-tests were performed to discern differences in animosity across two countries per group based on the GDP level (Australia vs. South Korea: t = 4.388, p < 0.001; Vietnam vs. Thailand: t = 4.008, p < 0.001). Countries in the same GDP category showed a significant difference in animosity among Chinese tourists, indicating the appropriateness of these destinations for this study.

Samples and procedure

To verify the wording and accuracy of measurement items, 10 respondents were recruited to complete an initial draft of the survey. Items were subsequently modified based on respondents’ feedback to eliminate ambiguity or other potential errors. A pre-test was then conducted using a convenience sampling approach before fieldwork commenced; 82 questionnaires were collected. Because the relationships proposed in the conceptual framework had not been researched before, we used partial least squares structural equation modelling to test focal constructs’ psychometric properties and to explore the conceptualized relationships via SmartPLS 3.3.7 (Hair et al., Citation2017). Findings did not reveal major concerns about variables’ reliability and validity. The conceptualized relationships showed an adequate model fit for a large-scale study.

The main study was performed in the autumn and winter of 2018. Each respondent was randomly assigned to one of the four destination countries and completed a corresponding survey. Data were gathered via convenience sampling of MBA alumni from universities in East China. A total of 415 questionnaires were collected in person during alumni events, 332 of which were valid. Another 289 valid electronic copies were returned via email. All respondents were assured of their anonymity and confidentiality to encourage transparent answers.

One-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were carried out across the on-site samples and the email samples. No significant demographic differences emerged between the two sample sets (Fgender = 1.107, df = 1, p > 0.20; Fincome = 2.002, df = 1, p > 0.10). We also compared both samples using a three-step permutation (i.e. assessing configural invariance; assessing the establishment of compositional invariance; and assessing equal means and variances) to examine the measurement invariance of composite models (MICOM) (Henseler et al., Citation2016). MICOM testing showed that both configural invariance and compositional invariance were established (see Appendix A). We then applied the Levene test as a post hoc analysis to examine the homogeneity of variance in data across the four countries after running an ANOVA. The Levene statistics for all variables were larger than 0.05 (see ), indicating that the population variances were homogeneous (Carvache-Franco et al., Citation2020).

Table 2. Equality stress test of variables across countries.

Results

Measurement model

lists the characteristics of the sample. We employed SmartPLS 3.3.7 to examine the hypothesized model relationships based on the measurement and structural models. The measurement model was used to evaluate constructs’ internal consistency, reliability, and convergent validity (Hair et al., Citation2017). All constructs were assessed as reflective measures, and the items for each construct demonstrated an appropriate degree of internal consistency; that is, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was greater than 0.70 (Nunnally, Citation1978) (). Constructs’ reliability was measured with composite reliability. All values exceeded 0.70, which is satisfactory (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2004).

Table 3. Sample characteristics.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics: reliability, validity, HTMT and Fornell-Larcker criterion.

The convergent validity and discriminant validity (Churchill, Citation1979) of four antecedents and two moderating constructs were tested next. Convergent validity was confirmed in every case based on outer loadings; all values (range: 0.715–0.946) were greater than the recommended minimum value of 0.708 (Hair et al., Citation2017), signalling a high proportion of variance across items within a construct ().

To ensure that multicollinearity was not an issue among the independent variables, discriminant validity was evaluated to determine the extent to which a construct differed from other constructs. Two approaches were applied. First, the Fornell–Larcker criterion was adopted by comparing the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) with the latent variable correlations (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2017). Discriminant validity was achieved, as the square root of the AVE for each construct (range: 0.529–0.867) surpassed 0.50; in other words, each construct explained more than half of the variance of its indicators (Espinoza, Citation1999) (). Second, the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) was considered to check whether the HTMT values for each pair of constructs in a matrix were below the conservative threshold of 0.85 (Hair et al., Citation2017). In addition, confidence intervals were computed via a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 samples to test whether the HTMT values were significantly different from 1. Neither of the confidence intervals included 1, confirming that discriminant validity was achieved (Hair et al., Citation2017).

We adhered to the full collinearity assessment approach proposed by Kock (Citation2015) and Hair et al. (Citation2017) to detect possible common method bias. The variance inflation factors (VIFs) of all items and independent variables were smaller than the recommended threshold of 3.3 as evidenced by the following inner VIF values: materialism = 1.000; prejudice = 1.025; admiration = 1.520; animosity = 1.214. Common method bias was therefore not a problem.

Structural model and tests of antecedent hypotheses

After examining the measurement model, the structural model was analyzed to investigate the hypothesized relationships. Path coefficients were assessed by examining the t-statistics using 5,000 bootstraps (). Table 5 lists the results of each path. H1, which suggested a positive and significant effect of materialism on admiration (H1: β = 0.118, p < 0.05), was supported: Chinese tourists expressing greater materialism expected to be admired for international travel. H2 was also supported (H2: β = 0.274, p < 0.001), illustrating a positive relationship between prejudice and animosity towards a destination country. H3 was supported as well (H3: β = 0.434, p < 0.001)—respondents’ expectations of being admired for visiting a destination significantly affected their travel intentions. Respondents’ animosity towards a destination country was found to exert a significantly negative impact on their travel intentions (β = −0.372, p < 0.001). As such, H4 was supported.

Table 5. Results of hypotheses testing.

We also assessed the coefficient of determination to identify the model’s predictive accuracy. The R2 value should ideally be between 0 and 1, with a higher value suggesting greater accuracy (Hair et al., Citation2017). The predictive accuracy of admiration and animosity leading to travel intention had R2 values of 0.251, 0.116, and 0.432, respectively. We next considered the Stone–Geisser Q2 value to discern the model’s predictive relevance. Endogenous variables with a Q2 value greater than 0 are considered satisfactory. By using the blindfolding procedure for an omission distance of D = 7 (Chin, Citation1998), the model displayed predictive relevance (Q2 > 0) (Hair et al., Citation2017) (see note in ).

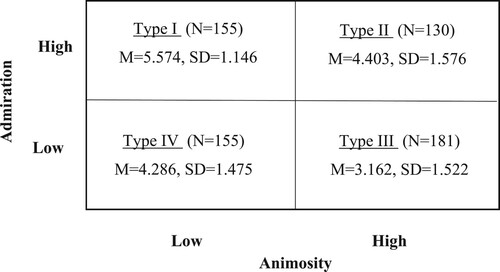

H5 was tested via one-way ANOVA (). Responses for the admiration and animosity scales were rank-ordered and divided into low and high groups using the scale median (i.e. 3.00 for admiration and 3.33 for animosity). The following four combinations were derived: Type I, high admiration–low animosity (n = 155); Type II, high admiration–high animosity (n = 130); Type III, low admiration–high animosity (n = 181); and Type IV, low admiration–low animosity (n = 155). These combinations then served as categorical variables to examine associations with travel intention. Significant differences were observed among the four ambivalence types for travel intention (F = 78.641; p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Attitude ambivalence: one-way ANOVA result. Note: Significantly different pairs according to Scheffe’s test (α = 0.05): Type I>II; Type I>III; Type I>IV; Type II>III; Type IV>III.

We used Scheffe’s test to compare the means of travel intention by type. The mean travel intention for Type I (M = 5.574) was significantly higher than for Type II (M = 4.403), Type III (M = 3.162), and Type IV (M = 4.286). The mean for Type II was significantly higher than that for Type III, as was the mean for Type IV. These findings lent support to H5: when ambivalence was low, tourists’ travel intentions were strongest for Type I and weakest for Type III. On the contrary, when ambivalence was high (Type II), tourists’ travel intentions were unclear. Type IV was associated with neither liking nor disliking the destination.

Test of moderating effects

An orthogonalizing approach was applied to examine the moderating effects of the country’s GDP at PPP and material happiness on the four antecedent hypotheses (Hair et al., Citation2017). GDP at PPP was presumed to have a moderating effect in H1 and H3. GDP at PPP significantly and positively enhanced the relationship between materialism and admiration (GDP*Materialism: β = 0.101, p < 0.05), suggesting a positive and stronger impact of materialism on admiration for countries with better economic development. H6a was supported as a result. However, no significant moderating effect was found for GDP at PPP on the relationship between admiration and travel intention. National economic development therefore had no moderating impact of admiration on travel intention (GDP*Travel intention: β = 0.048, p > 0.1), and H6b was not supported (Table 5).

The findings also demonstrated a significant moderating effect of material happiness on two out of the four antecedent hypotheses: H2 and H4. Material happiness played a significant moderating role in the relationship between prejudice and animosity (Material happiness*Prejudice: β = 0.115, p < 0.001). The relationship between prejudice and animosity towards a specific country was thus stronger among respondents who scored higher on material happiness. H7a was accordingly supported. Material happiness also moderated the relationship between animosity and travel intention (Material happiness*Animosity: β = - 0.067, p < 0.01), indicating that animosity’s negative effect on respondents’ intentions to visit a specific country was especially pronounced when people possessed greater material happiness. Hence, H7b was also supported.

Discussion and conclusion

This study expands the tourism literature by highlighting the impacts of multiple identities on individuals’ emotions and travel intentions. First, findings contribute to identity research within the tourism domain by underlining the roles of international tourists’ multiple identities in their attitudes towards overseas destinations. Tourists’ interactions with in-groups and out-groups amplify their group identity, such that tourists tend to compromise their personal interests to abide by the group’s collective goals around tourism consumption (Shavitt & Barnes, Citation2020). This propensity is especially salient in a collectivist society, where individuals are more likely to conform to a group identity to maintain harmonious relationships (Alvarez & Campo, Citation2020; Shrum et al., Citation2013). Tourists’ group identity is highly relevant in international tourism: people from collective societies are willing to sacrifice their self-interests for collective interests, such as avoiding visiting places that in-group members dislike (Zhang et al., Citation2019).

Second, in bolstering the thin literature on ambivalence in tourism (Chen et al., Citation2019; Kim & Um, Citation2016), this study substantiates consumer research on ambivalence showing that incongruent personal and group identities can produce emotions that elicit ambivalence; meanwhile, one’s behaviour becomes less predictable when they are highly ambivalent (Glasman & Albarracín, Citation2006). This outcome offers further insight into tourists’ destination selection.

Finally, results reveal that tourism products which are expensive, exclusive, exotic, and/or difficult to access function similarly to prestige-worthy products that help materialists express social status and boost their perceived social audience admiration (Gieling & Ong, Citation2016; Richins & Dawson, Citation1992). Materialists from developing countries expect to receive social audience admiration upon visiting developed countries, echoing consumers’ brand preferences based on country of origin (Eng et al., Citation2016). Somewhat surprisingly, a destination country’s economic development does not necessarily inform individuals’ travel decisions. These findings accord with earlier indications that people seek to identify with strong and attractive groups in order to gain admiration (Fisher & Wakefield, Citation1998). Individuals may consider other crucial factors when choosing a tourism destination, such as cost, ease of access, and international relationships (Czaika & Neumayer, Citation2017).

Managerial implications

This study offers several implications for marketing practitioners and tourism stakeholders, especially in destinations that are heavily dependent on inbound tourists. A shifting geopolitical landscape between places, nations, and people is moulding international tourism as nationalism and anti-globalization surge (Correia et al., Citation2016). High ambivalence caused by mixed or contradictory emotions may arise more frequently and impede tourists from visiting destinations that could trigger contradictory reactions. This social phenomenon should drive marketers and destination managers to find ways to minimize tourist ambivalence.

One suggestion is to provide offerings that generate positive emotions, such as exclusive products with symbolic features to attract materialistic tourists who seek social audience admiration (Eng et al., Citation2016; Hyman, Citation1960). Prestige products can be designed based on natural characteristics (e.g. an underwater hotel room/restaurant in Maldives, a glass-top corridor at Zhangjiajie in China, glass igloos in Finland) or cultural specialities (e.g. Santa Claus Village in Finland, Jacobite steam train/Hogwarts Express in Scotland). Customized offerings may also be developed, such as a night desert safari with exclusive services and facilities, an exotic dinner with a special performance, or a luxurious shopping experience with tailored services. In response to the demand for such products and services, tourism providers may consider different ways to segment the market. Tactics could include premier pricing, exclusive memberships, advance booking options, loyalty schemes, and admission limits to underscore offerings’ scarcity.

Additionally, destination authorities need to consider inbound tourists’ cultural identities, monitor negative reactions, and remove products or services that could cause humiliation or discrimination (Yang et al., Citation2020). People from different cultures may resolve the ambivalence caused by internal emotional conflicts in distinct ways. Amid a swift rise in individual wealth in emerging economies, materialists from collectivist societies may be more willing to demonstrate success through material possessions (Dutot, Citation2020).

People who pursue a high level of material happiness have been shown to exhibit more prejudice and animosity towards a destination country as they aim to adhere to their in-group ethnic identity; as such, these individuals are more likely to give up certain forms of consumption in favour of collective ideals when facing an acute crisis in intergroup relations (Shrum et al., Citation2013). They are also more apt to conduct an internal negotiation between their collective and self-oriented interests related to the acquisition and possession of material goods to gain support from in-group members (Awanis et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it is crucial to monitor bilateral relationships between destination countries/regions and their source markets. The same need applies to international trade partners: tourism stakeholders must understand whether key customers hail from a collectivist culture or hold a strong national/ethnic-racial identity (Unger et al., Citation2021). Marketers should be particularly cautious about arousing existing prejudices and negative emotions (e.g. animosity). These professionals should also consider whether such feelings are historical or associated with specific events, such as political tension or cultural misunderstandings (Yu et al., Citation2019). Strategic plans should be devised for major source markets with historical animosity. A destination’s capacity to receive customers from a particular market should be carefully evaluated as well. If animosity follows from cultural misunderstandings or accidents, crisis management teams should endeavour to assuage negative reactions immediately (Yu et al., Citation2019).

Limitations and future research

The limitations of this study open avenues for future investigation. First, the two emotions profiled herein, animosity and admiration, are starting points; other emotions merit exploration. Additionally, prejudice and animosity were discussed from a group identity perspective. Consumers’ emotional responses to tourism products may vary significantly (Campo & Alvarez, Citation2017) and should be examined further.

Second, apart from the debate on which approach (subjective vs. objective) is superior for measuring ambivalence, it can be challenging to pinpoint which components of an object generate emotions that may lead to ambivalence. Few people are cognizant of, or can precisely describe, what prevents them from making a decision (Thompson et al., Citation1995). More creative research methods should be leveraged to capture ambivalence. In addition, people from different cultures may deploy specific strategies to resolve ambivalence caused by internal emotional conflicts. East Asians tend to view simultaneous positive and negative emotions dialectically and holistically, whereas people from individualist societies such as the United States find concurrent positive and negative emotions to be more conflictual (Bagozzi et al., Citation1999).

Third, the effects of social identity and emotions in this study may be distinct from those in other developing countries such as the Philippines, Brazil, or Nigeria. China scores high on cultural collectivism wherein group cohesion is emphasized; citizens are hence more inclined to work together to support a common cause (Hofstede, Citation2007). Meanwhile, modern Chinese culture places more weight on achievements, autonomy, egalitarianism, utilitarianism, and quality of life (Hu et al., Citation2018). Instead of using material happiness to test the moderating effect between the relationships of social identity, emotions, and travel intention, other self-construal constructs may be considered. Moreover, people’s perceptions of a country can change due to international relationships, incidents, or media reports. Emotions related to different out-groups may evolve over time as well. Subsequent research should focus on these phenomena under various circumstances. Finally, study data were limited to MBA students and alumni in one country. This group is fairly socioeconomically privileged and limits findings’ generalizability. Interested scholars should adopt more heterogenous sampling strategies in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abraham, V., & Poria, Y. (2020). Political identification, animosity, and consequences on tourist attitudes and behaviours. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(24), 3093–3110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1679095

- Agrawal, N., & Maheswaran, D. (2005). The effects of self-construal and commitment on persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(4), 841–849. https://doi.org/10.1086/426620

- Alvarez, M. D., & Campo, S. (2014). The influence of political conflicts on country image and intention to visit: A study of Israel’s image. Tourism Management, 40, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.05.009

- Alvarez, M. D., & Campo, S. (2020). Consumer animosity and its influence on visiting decisions of US citizens. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(9), 1166–1180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1603205

- Awanis, S., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Cui, C. C. (2017). Asia’s materialists: Reconciling collectivism and materialism. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(8), 964–991. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-017-0096-6

- Bagozzi, R. P., Wong, N., & Yi, Y. J. (1999). The role of culture and gender in the relationship between positive and negative affect. Cognition and Emotion, 13(6), 641–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999399379023

- Ballesteros, E. R., & Ramìrez, M. H. (2007). Identity and community — Reflections on the development of mining heritage tourism in southern Spain. Tourism Management, 28(3), 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.03.001

- Bar-Tal, D., & Avrahamzon, T. (2017). Development of delegitimization and animosity in the context of intractable conflict. In C. Sibley & F. K. Barlow (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of the Psychology of prejudice (pp. 582–606). Cambridge University Press.

- Bar-Tal, D., & Teichman, Y. (2005). Stereotypes and prejudice in conflict: Representations of Arabs in Israeli Jewish society. Cambridge University Press.

- BBC News. (2020). Coronavirus: Student from Singapore hurt in Oxford Street attack. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-51722686

- Blackhall, M. (2019). Global tourism hits record highs – but who goes where on holiday, the Guardian. Retrieved May 21, 2019, from https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/jul/01/global-tourism-hits-record-highs-but-who-goes-where-on-holiday

- Blank, A. S., Koenigstorfer, J., & Baumgartner, H. (2018). Sport team personality: It’s not all about winning!. Sport Management Review, 21(2), 114–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.05.004

- Bond, N., & Falk, J. (2013). Tourism and identity-related motivations: Why am I here (and not here)? International Journal of Tourism Research, 15(5), 430–442. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1886

- Campo, S., & Alvarez, M. D. (2014). Can tourism promotions influence a country's negative image? An experimental study on Israel's image. Current Issues in Tourism, 17(3), 201–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.766156

- Campo, S., & Alvarez, M. D. (2017). Consumer animosity and affective country image. In A. Correia, M. Kozak, J. Gnoth, & A. Fyall (Eds.), Co-creation and well-being in tourism (pp. 119–131). Springer.

- Carvache-Franco, M., Carvache-Franco, W., Carvache-Franco, O., Hernández-Lara, A. B., & Buele, C. V. (2020). Segmentation, motivation, and sociodemographic aspects of tourist demand in a coastal marine destination: A case study in Manta (Ecuador). Current Issues in Tourism, 23(10), 1234–1247. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1600476

- Chattaraman, V., Lennon, S. J., & Rudd, N. A. (2010). Social identity salience: Effects on identity-based brand choices of Hispanic consumers. Psychology & Marketing, 27(3), 263–284. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20331

- Chen, Z., Wang, Y., Li, X., & Lawton, L. (2019). It’s not just black or white: Effects of ambivalence on residents’ support for a mega-event. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 43(2), 283–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348018804613

- Chin, W. W. (1998). The partial least squares approach for structural equation modeling. In G. A. Marcoulides (Ed.), Modern methods for business research (pp. 295–336). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- ChinaDaily. (2018). UNWTO Report Highlights China Role in Global Outbound Tourism. Retrieved December 28, 2019, from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/201808/28/WS5b8506fca310add14f3883a2.html

- Choma, B. L., Jagayat, A., Hodson, G., & Turner, R. (2018). Prejudice in the wake of terrorism: The role of temporal distance, ideology, and intergroup emotions. Personality & Individual Differences, 123, 65–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.11.002

- Chugani, S., & Irwin, J. R. (2020). All eyes on you: The social audience and hedonic adaptation. Psychology & Marketing, 37(11), 1554–1570. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21401

- Churchill, G. A. (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377901600110

- Correia, A., Kozak, M., & Del Chiappa, G. (2020). Examining the meaning of luxury in tourism: A mixed-method approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(8), 952–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1574290

- Correia, A., Kozak, M., & Reis, H. (2016). Conspicuous consumption of the elite: Social and self-congruity in tourism choices. Journal of Travel Research, 55(6), 738–750. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514563337

- Correia, A., & Moital, M. (2009). Antecedents and consequences of prestige motivation in tourism: An expectancy-value motivation. In M. Kozak, & A. Decrop (Eds.), Handbook of tourist behaviour—theory and practice (pp. 16–32). Routledge.

- Czaika, M., & Neumayer, E. (2017). Visa restrictions and economic globalisation. Applied Geography, 84, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.04.011

- Dai, B., Jiang, Y., Yang, L., & Ma, Y. (2017). China’s outbound tourism – stages, policies and choices. Tourism Management, 58, 253–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.03.009

- Desforges, L. (2000). Traveling the world: Identity and travel biography. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(4), 926–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00125-5

- Dutot, V. (2020). A social identity perspective of social media’s impact on satisfaction with life. Psychology & Marketing, 37(6), 759–772. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21333

- Eng, T., Ozdemir, S., & Michelson, G. (2016). Brand origin and country of production congruity: Evidence from the UK and China. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5703–5711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.045

- Espinoza, M. M. (1999). Assessing the cross-cultural applicability of a service quality measure: A comparative study between Quebec and Peru. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 10(5), 449–468. https://doi.org/10.1108/09564239910288987

- Fisher, R. J., & Wakefield, K. (1998). Factors leading to group identification: A field study of winners and losers. Psychology & Marketing, 15(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199801)15:1<23::AID-MAR3>3.0.CO;2-P

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Gal, D. (2015). Identity-signalling behaviour. In M. I. Norton, D. D. Rucker, & C. Lamberton (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of consumer psychology (pp. 257–281). Cambridge University Press.

- Gardner, P. L. (1987). Measuring ambivalence to science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 24(3), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660240305

- Gieling, J., & Ong, C. (2016). Warfare tourism experiences and national identity: The case of airborne museum ‘Hartenstein’ in Oosterbeek, the Netherlands. Tourism Management, 57, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.017

- Glasman, L. R., & Albarracín, D. (2006). Forming attitudes that predict future behaviour: A meta-analysis of the attitude-behaviour relation. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5), 778–822. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.778

- Goldsmith, R. E., & Clark, R. (2012). Materialism, status consumption, and consumer independence. The Journal of Social Psychology, 152(1), 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2011.555434

- Guo, X. (2013). Living in a global world: Influence of consumer global orientation on attitudes toward global brands from developed versus emerging countries. Journal of International Marketing, 21(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1509/jim.12.0065

- Hair, F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed). Sage.

- Harreveld, v. F., Nohlen, H. U., & Schneider, I. K. (2015). The ABC of ambivalence: Affective, behavioural, and cognitive consequences of attitudinal conflict. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 285–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2015.01.002

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 405–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-09-2014-0304

- Hofstede, G. (2007). Asian management in the 21st century. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 24(4), 411–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-007-9049-0

- Hogg, M. A. (2000). Social identity and social comparison. In J. Suls & L. Wheeler (Eds.), Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research (pp. 401–421). Springer Science Business Media.

- Hogg, M. A., & Terry, D. J. (2000). Social identity and self-categorisation processes in organisational context. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2000.2791606

- Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., & White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(4), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787127

- Hu, X., Chen, S. X., Zhang, L., Yu, F., Peng, K., & Liu, L. (2018). Do Chinese traditional and modern cultures affect young adults’ moral priorities? Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1799. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01799

- Hyman, H. H. (1960). Reflections on reference groups. Public Opinion Quarterly, 24(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.1086/266959

- Ivanic, A. S. (2015). Status has its privileges: The psychological benefit of status-reinforcing behaviours. Psychology & Marketing, 32(7), 697–708. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20811

- Jang, S., & Wu, C. M. E. (2006). Seniors’ travel motivation and the influential factors: An examination of Taiwanese seniors. Tourism Management, 27(2), 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.11.006

- Kelman, H. C. (1961). Process of opinion change. Public Opinion Quarterly, 25(Spring), 57–78. https://doi.org/10.1086/266996

- Kim, S. M., & Um, K. H. (2016). The effects of ambivalence on behavioural intention in medical tourism. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 21(9), 1020–1045. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2015.1093515

- Klein, J. G., Ettenson, R., & Morris, M. D. (1998). The animosity model of foreign product purchase: An empirical test in the People’s Republic of China. Journal of Marketing, 62(January), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299806200108

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Li, X. (ed.). (2016). Chinese outbound tourism 2.0. Apple Academic Press/CRC Press- Taylor & Francis Group.

- Liao, J., & Wang, L. (2017). The structure of the Chinese material value scale: An eastern cultural view. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1852. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01852

- Little, J. P., & Singh, N. (2014). An exploratory study of Anglo-American consumer animosity toward the use of the Spanish language. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 22(3), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679220306

- MacCannell, D. (1976). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. Schocken Books.

- Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224

- Moufakkir, O. (2014). What’s immigration got to do with it? Immigrant animosity and its effects on tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.008

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Olsen, S. O., Wilcox, J., & Olsson, U. (2005). Consequences of ambivalence on satisfaction and loyalty. Psychology & Marketing, 22(3), 247–269. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20057

- Onwezen, M. C., Reinders, M. J., & Sijtsema, S. J. (2017). Understanding intentions to purchase bio-based products: The role of subjective ambivalence. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 52, 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.05.001

- Otnes, C., Lowrey, T. M., & Shrum, L. J. (1997). Toward and understanding of consumer ambivalence. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1086/209495

- Ouellet, J. F. (2007). Consumer racism and its effects on domestic cross-ethnic product purchase: An empirical test in the United States, Canada, and France. Journal of Marketing, 71(1), 113–128. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.71.1.113

- Palmer, A., Koenig-Leis, N., & Jones, L. E. M. (2013). The effects of residents’ social identity and involvement on their advocacy of incoming tourism. Tourism Management, 38, 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.02.019

- Palmer, C. (1999). Tourism and the symbols of identity. Tourism Management, 20(3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(98)00120-4

- Palmer, C. (2005). An ethnography of Englishness. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.04.006

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, Psychonomic Society Inc., 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553

- Priest, N., Walton, J., White, F., Kowal, E., Baker, A., & Paradies, Y. (2014). Understanding the complexities of ethnic-racial socialisation processes for both majority groups: A 30-year systematic review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 43, 139–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.08.003

- Proulx, T., Inzlicht, M., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2012). Understanding all inconsistency compensation as a palliative response to violated expectations. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16(5), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.04.002

- Randers, L., Grønhøj, A., & Thøgersen, J. (2021). Coping with multiple identities related to meat consumption. Psychology & Marketing, 38(1), 159–182. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21432

- Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1086/209304

- Rutlad, A. (1999). The development of national prejudice, in-group favouritism and self-stereotypes in British children. British Journal of Social Psychology, 38(1), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466699164031

- Sánchez, M., Campo, S., & Alvarez, M. D. (2018). The effect of animosity on the intention to visit tourist destinations. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 7, 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2016.11.003

- Shavitt, S., & Barnes, A. J. (2020). Culture and the consumer journey. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.11.009

- Shrum, L. J., Wang, N., Arif, F., Chugani, S. K., Gunz, A., Lowrey, T. M., Nairn, A., Pandelaere, M., Ross, S. M., Ruvio, A., Scott, K., & Sundie, J. (2013). Reconceptualising materialism as identity goal pursuits: Functions, processes, and consequences. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 179–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.08.010

- Smith, R. H. (2000). Assimilative and contrastive emotional reactions to upward and downward social comparisons. In Suls, & Wheeler (Eds.), Handbook of social comparison: Theory and research (pp. 173–200). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

- Sparks, P., Conner, M., James, R., Shepherd, R., & Povey, R. (2001). Ambivalence about health-related behaviours: An exploration in the domain of food choice. British Journal of Health Psychology, 6(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910701169052

- State Administration of Foreign Exchange. (2018). The central parity of RMB exchange rate on September 13, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2019, from https://www.safe.gov.cn/beijing/2018/0914/932.html

- Stets, J. E., & Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(3), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695870

- Swaminathan, V., Page, K. L., & Gürhan-Canli, Z. (2007). ‘My’ brand or ‘our’ brand: The effects of brand relationship dimensions and self-construal on brand valuations. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1086/518539

- Tajfel, H. (1972). Social categorisation. English manuscript of ‘La Catégorisation Sociale’. In S. Moscovici (Ed.), Introduction à la Psychologie Sociale (Vol. 1) (pp. 272–302). Larousse.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1987). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Nelson Hall.

- The World Bank. (2019). GDP (current US$). Retrieved December 28, 2019, from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD

- Thompson, M. M., Zanna, M. P., & Griffin, D. W. (1995). Let’s not be indifferent about (attitudinal) ambivalence. In R. E. Petty & J. A. Krosnick (Eds.), Attitude strength: Antecedents and consequences, Ohio State University series on attitudes and persuasion (Vol. 4: pp. 361–386). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Triandis, H. C., McCusker, C., & Hui, C. H. (1990). Multimethod probes of individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 59(5), 1006–1020. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1006

- Unger, O., Uriely, N., & Fuchs, G. (2021). On-site animosity and national identity: Business travellers on stage. Annuals of Tourism Research, 88, 103181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103181

- Vigneron, F., & Johnson, L. W. (1999). A review and a conceptual framework of prestige-seeking consumer behaviour. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 9(1), 1–14.

- Wang, Y., Wu, L., Xie, K., & Li, X. (2019). Staying with the ingroup or outgroup? A cross-country examination of international travellers’ home-sharing preferences. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.08.006

- Yang, I., French, J. A., & Lee, C. (2020). The symbolism of international tourism in national identity. Annals of Tourism Research, 83, 102966. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102966

- Yang, Y., Liu, H., Li, X., & Harrill, R. (2018). A shrinking world for tourists? Examining the changing role of distance factors in understanding destination choices. Journal of Business Research, 92, 350–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.08.001

- Yu, Q., McManus, R., Yen, D. A., & Li, X. (2019). Tourism boycotts and animosity: A study of seven events. Annals of Tourism Research, 80, 102792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102792

- Zhang, C. X., Pearce, P., & Chen, G. (2019). Not losing our collective face: Social identity and Chinese tourists’ reflections on uncivilised behaviour. Tourism Management, 73, 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.01.020

Appendices

Appendix A

Results of invariance measurement testing using permutation.

Appendix B

Fit indices for the multi-group SEM analysis – invariance test results.