ABSTRACT

The economic turmoil and restrictions on human movement precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic severely impacted conservation efforts. Many conservation actors rapidly implemented various adaptive measures in response to the cessation of the nature-based tourism industry, the primary revenue source for much of conservation in sub-Saharan Africa. This timely preliminary study examined the innovative use of virtual safaris, a form of virtual nature-based tourism, as an adaptive response to the crisis. Eight in-depth semi-structured interviews and two written responses from a range of ‘conservation operators’ provided insight into motivations, benefits, and challenges associated with using virtual safaris. This novel study found three mechanisms through which virtual safaris helped to alleviate the effects of COVID-19 with the potential to develop conservation resilience: 1) as a stopgap measure, 2) for revenue diversification, and 3) as a means of scaling ecosystem services. Virtual safaris provided a critical lifeline for conservation operators, created a new tool to connect with distant audiences, and strengthened relationships with donors. However, this research highlighted a need to re-evaluate the role of sustainable tourism within conservation, with transformative changes essential to enhance future conservation resilience.

Introduction

From March 2020, the SARS-CoV-2 virus (COVID-19) pandemic has caused overwhelming disruption to almost all sectors of life. Governments worldwide responded by introducing drastic interventions to curb the spread of COVID-19, including international border closures, stay-at-home ‘lockdowns’, and social distancing (Gössling et al., Citation2020). While designed to protect the public, the measures resulted in significant socio-economic impacts, challenging businesses and industries in a ‘hyper-mobilised and hyper-connected world’ (Searle et al., Citation2021, p. 3) to adapt to a world of physical immobility.

The pandemic quickly raised concerns regarding impacts for biodiversity conservation at local, regional, and global levels (Waithaka et al., Citation2021). Initially, many environmental impact reports were positive, however, such effects were predicted to be short-term (Smith et al., Citation2021), and ‘prone to reversal’ (Lindsey et al., Citation2020, p. 1302). Competition for funds from both governments and private philanthropic donors grew as financial resources were channelled into global health measures (Corlett et al., Citation2020) with economic recovery plans in African countries scarcely referencing conservation (Kroner et al., Citation2021).

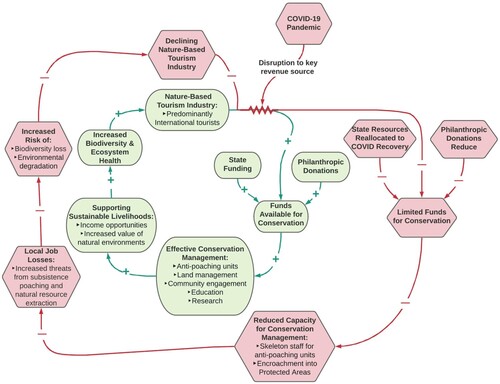

In sub-Saharan Africa, a major concern was the dramatic loss of revenue associated with nature-based tourism (Gibbons et al., Citation2021), which fuelled a significant proportion of conservation activities, and provided livelihoods for communities surrounding protected and conserved areas (Hockings et al., Citation2020; Lindsey et al., Citation2020; Waithaka et al., Citation2021). Prior to the pandemic, nature-based tourism contributed US$29.3 billion in gross domestic product across the African continent in 2018 (WTTC, Citation2019) and supported 1.5 million jobs in South Africa alone (TBCSA, Citation2020). However, as of May 2021 international arrivals for Africa were 81% below 2019 levels (UNWTO, Citation2021). In response, tour operators in South Africa reduced pricing and staff, implemented pay cuts, and sought innovative forms of marketing and product diversification to survive the economic hardship (Giddy & Rogerson, Citation2021). This created a ‘perfect storm’ of diminished conservation capacity and increased threats from subsistence and organized poaching driven by job losses and economic instability (Lendelvo et al., Citation2020; Lindsey et al., Citation2020). These impacts are summarized in .

Figure 1. Model of the financial relationship between conservation and tourism (green circles) and the resulting negative impacts on conservation (red hexagons) caused by COVID-19 disruptions. Adapted from Lindsey et al. (Citation2020).

The dependency of conservation efforts on the tourism industry has been the subject of academic critique for over a decade (Brockington & Duffy, Citation2010; Büscher et al., Citation2012; Igoe & Brockington, Citation2007; Sandbrook et al., Citation2020). COVID-19 reignited the debate by exposing the fragility of the conservation-tourism relationship, prompting academics and practitioners alike to question how to manage the crisis and improve the resilience of conservation to future external shocks (Lindsey et al., Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2021). As well as being fragile and unsustainable, the current model of conservation is argued to be predicated on the language of neoliberal economics and the commodification of natural resources (Sullivan, Citation2006), which ‘functions to entrain nature to capitalism’ (Büscher et al., Citation2012, p. 7). Within this context, the pandemic had been viewed as a watershed moment to re-evaluate the sustainability of the tourism industry (Gössling et al., Citation2020; Higgins-Desbiolles, Citation2020) and ‘build resilience within protected area tourism as a regenerative conservation tool’ (Spenceley et al., Citation2021, p. 103). Others highlighted opportunities to fundamentally reimagine conservation practice by moving beyond the problematic, though economically critical, relationship with tourism (Fletcher et al., Citation2020; Kideghesho et al., Citation2021; Lindsey et al., Citation2020).

Whilst posing significant challenges for conservation, the pandemic also presented new opportunities as people turned to virtual spaces to connect with the world outside of their homes. Virtual experiences of nature and travel via live webcams (Jarratt, Citation2020), virtual reality technology (Hofman et al., Citation2022; Verkerk, Citation2022), and video conferencing technology dramatically increased in popularity (Turnbull et al., Citation2020). Notwithstanding the ‘overwhelming and immediate demand’ (Turnbull et al., Citation2020, p. 6.2) for virtual experiences of nature during lockdowns, the novel use of ‘virtual safaris’ as a form of virtual nature-based tourism (VNBT) had (at the time of publication) received little academic attention. In sub-Saharan Africa, media commentators reported a rise in game reserves and lodges using virtual safaris to keep people engaged with nature and to help fund conservation efforts (Globetrender, Citation2020). This preliminary research sought to elucidate the use of virtual safaris by ‘conservation operators’ (actors who engage directly in or support conservation initiatives) and explore the potential of VNBT to contribute to conservation resilience. The study investigated three research questions concerning the use of virtual safaris. First, how was the use of virtual safaris developed in response to the impacts of COVID-19? Second, what were the outcomes of adopting virtual safaris for conservation operators? And last, how could VNBT contribute to conservation going forward?

Background

Collectively, virtual or remote experiences of nature are herein referred to as VNBT. Since there is currently no definition of VNBT, this study combines definitions of virtual experience (Cho et al., Citation2002), virtual tourism (Mura et al., Citation2017), and nature-based tourism (Leung et al., Citation2018) to describe VNBT as the activities of visitors engaging in digitally-mediated experiences involving the ‘telepresence’Footnote1 of visitors in remote natural environments. Research has explored the value of virtual experiences of nature for encouraging conservation behaviour (Hofman et al., Citation2022), including how it can increase people’s access to nature when due to individual circumstances, in-person experiences were not feasible (Fennell, Citation2021; Filter et al., Citation2020). Searle et al. (Citation2021) proposed that virtual experiences of nature throughout lockdown provided ‘participatory platforms for public engagement and ecological awareness raising’ (p. 6). Previously, Skibins and Sharp (Citation2018, p. 11) found that live virtual experiences of wildlife formed an effective conservation tool to provide ‘a global reach, minimise [environmental] impacts, overcome socio-economic barriers, and provide multiple points of engagement across cultures’.

In the wake of COVID-19 there has been a proliferation of novel forms of VNBT. Literature suggests that particular forms of VNBT, which ‘produce affects and interpersonal relations through liveness’ (Turnbull et al., Citation2020, p. 6.8), demonstrate important differences compared to other virtual experiences of nature, such as documentaries (Jarratt, Citation2020). Gretzel et al. (Citation2020) called for a transformative approach to researching e-Tourism, or virtual tourism, in response to the technological orientation of the world following COVID-19 conditions. Importantly, virtual tourism may have the potential to provide a more sustainable alternative to conventional carbon-intensive travel (Akhtar et al., Citation2021; Lu et al., Citation2021).

To date Giddy and Rogerson (Citation2021) and Verkerk (Citation2022) are the only two studies to explicitly, although briefly, use the term ‘virtual safaris’ in reference to adaptive responses to impacts of COVID-19 in South Africa. Verkerk (Citation2022) described the barriers and abilities of different forms of virtual tourism, with virtual safaris (also referred to as ‘live-streamed safaris’ within the study) being one method to ‘save’ the tourism industry in South Africa from the detrimental effects of COVID-19. A third study, Glenn (Citation2021), explored virtual safaris, under the term ‘telesafaris’, as a new genre of wildlife documentary and argued the interactivity of live-streamed safaris is important for facilitating an authentic experience through fostering connections with nature and the safari guides. However, there remains a lack of research dedicated to understanding virtual safaris and the potential contributions towards conservation resilience. This study addresses the gap in the literature by drawing on in-depth semi-structured interviews with conservation operators in sub-Saharan Africa to examine their unique perspectives and experiences of virtual safaris and the associated challenges and benefits of their use.

Methodology

A qualitative approach was adopted to explicitly understand approaches to management and to give insights on the decision-making process amongst conservation operators who engaged with virtual safaris during the pandemic. Semi-structured interviews elicited rich insights into the experiences of diverse conservation operators, recognizing that individual responses and perspectives were often mediated by personal experiences, proving valuable for ‘generating contextual understandings of a defined conservation topic or problem’ (Moon & Blackman, Citation2014, p. 1172).

Study design

The conversational form of semi-structured interviews allowed flexibility in exploring respondents’ specific experiences, perceptions, and concerns (Valentine, Citation2005). Separate interview guides were prepared for each respondent (example Appendix I) to ensure key topics were discussed (Newing et al., Citation2010). Themes raised by respondents were incorporated into subsequent interviews in an iterative research process to corroborate responses and understand topics from a range of industry perspectives (Bryman, Citation2012).

Interviews lasted between 40-90 minutes and were conducted remotely via Zoom with conservation operators who provided virtual safaris between March 2020 and July 2021. Ethical approval was granted by the University of Bristol School of Geographical Sciences Research Ethics Committee (reference: RE-B-BARKER-20210514) and written informed consent was obtained before each interview. Purposive sampling was employed to gain knowledge from key informants with direct experiences of virtual safaris (Newing et al., Citation2010). Searches of online platforms such as Instagram, Google, and Facebook for keywords including ‘virtual safari’, ‘sofa safari’, and ‘live safari’ were used to identify organizations who had engaged with virtual safaris. As virtual safaris are an emergent form of VNBT, there were only a limited number of organizations, almost exclusively located in sub-Saharan Africa, who had engaged in such practices before July 2021. Eighteen organizations were contacted via email and invited to interview, of which eight agreed to interviews and two provided written responses to the interview questions. A limitation to this study was that the COVID-19 pandemic reduced access to respondents. Four organizations contacted for interviews were unavailable due to limited staff and changing COVID-19 regulations. To compensate for this, two respondents provided written responses. However, it is acknowledged these two responses were significantly less detailed and did not provide the same depth as interviews.

Respondents consisted of a range of conservation operators within three main categories: Broadcasters (B) were companies that specialized in live virtual safaris, Conservation Charities (C) were organizations that raised funds for conservation and/or directly undertook conservation activities, and Game Reserves (G) represented safari lodges, camps, or private game reserves. Written informed consent for the publication of their details was obtained from the respondents.

Data analysis

The interview transcripts and written responses were compiled and analysed using NVivo (QSR International, Citation2020) following Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) thematic analysis process: familiarization with the data, code generation, identifying themes, and reviewing the analysis of themes against the research questions and data. Initial codes were generated based on the three research questions and emergent topics (Appendix II). These were subsequently organized into broad but ‘coherent, consistent, and distinctive’ (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 96) themes, for example: the effects of COVID-19, approaches towards virtual safari use, motivations for employing virtual safaris, the associated challenges and benefits, and attitudes towards future use.

Results

The results section begins by outlining the diverse approaches developed to virtual safaris during the pandemic and the respondents’ motivations to engage with them. It then describes the outcomes in terms of the benefits and challenges of virtual safaris as a conservation tool for respondents, and lastly explores respondents’ attitudes on the future use of virtual safaris post COVID-19.

Development: approaches

This study found ‘virtual safari’ to be an umbrella term for a virtual experience of nature involving a guided journey through the African bush in an open vehicle to view wildlife, the scenery, and learn about the environment. Considerable heterogeneity existed amongst the approaches developed (see ) and respondents drew critical distinctions between what should or should not be labelled a virtual safari. WildEarth(B) and Painteddog.tv(B) expressed frustration at the lack of differentiation between those who specialize in virtual safaris and those who improvised ‘makeshift’ virtual safaris via social media. There was disagreement about how that differentiation should be made. Painteddog.tv(B) suggested that differentiation should be determined by ‘a certain level of expertise and dedication’, whereas WildEarth(B) felt that virtual safaris should be defined by their ability to replicate an in-person safari through creating telepresence:

People are obviously broadcasting on social media from their phones, but I don’t consider that a virtual safari … it does not create presence for the viewer. So, the definition of a virtual safari, just like a physical safari, is presence.

Table 1. Different approaches to virtual safaris showing the breakdown of variable elements.

In addition to virtual safaris, this study identified live ‘virtual conservation experiences’ (VCEs) as a discrete form of VNBT. VCEs differ from virtual safaris in that the event is directly related to a conservation operation, such as an elephant collaring or rhinoceros dehorning. Elephants Alive!(C) felt that such live events provided viewers with the opportunity to see conservation in action and to show their support for those undertaking conservation activities.

Development: motivations

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic influenced respondents’ motivations to engage with virtual safaris. Most experienced a dramatic decrease or a complete halt in funding. Game Reserves reported that their businesses and conservation work were brought to a ‘blinding stop’ (Lodge A(G)) as they experienced ‘a massive, massive downfall’ (Lodge B(G)) in revenue because of travel restrictions. They were quick to launch free-to-view virtual safaris primarily for marketing purposes to encourage future in-person visits: ‘Keeping ourselves relevant, sending messages out there that ‘we’re still here, animals are still here’ … trying to whet peoples’ appetite … there was nothing else we could do’ (Lodge B(G)).

Conservation Charities saw a reduction in philanthropic donations and observed the effects it had on their partners and projects on the ground, with AWF(C) reflecting that ‘[when] there are no tourism dollars there are no wildlife dollars’. Exclusive pay-to-view experiences were launched for funding (DSWF(C), Elephants Alive!(C), Kariega(C)) and free-to-view experiences aimed to strengthen donor relationships (AWF(C)).

Meanwhile, Broadcasters experienced increases in viewership; over four days in March 2020 almost immediately after the pandemic broke, WildEarth(B) recorded a fivefold increase in viewership.

Outcomes: benefits

Throughout the interviews, the benefits were more frequently discussed than the challenges associated with conducting virtual safaris (). Overall, all three categories of respondents highlighted their beneficial experiences of using virtual safaris in relation to ‘access’, ‘marketing’, ‘revenue’, and ‘awareness & education’. ‘Access’ was reported as a key benefit by 90% of respondents whereby virtual safaris simultaneously increased people’s access to nature as well as enabled organizations to have a ‘global reach’ (DSWF(C)) for connecting and engaging with people through a virtual medium. Additionally, virtual safaris offered a sustainable ‘travel alternative’ and provided access for those who, ‘whether it’s for health, whether it’s for financial means’ (AWF(C)), are not able to visit in person.

Table 2. Summary of the benefits and challenges associated with virtual safaris, the frequency mentioned, the percentage of respondents who raised them, and the category of respondents who mentioned the themes (B: Broadcasters, C: Conservation Charities, G: Game Reserves).

Virtual safaris also facilitated interactions with individuals on the ground in sub-Saharan Africa and respondents felt that they acted as a ‘bridging point between different conservation organizations and keeping people involved’ (Lodge A(G)). For Conservation Charities, this translated into an improved ability to engage with donors and demonstrate how their donations supported those undertaking conservation work. The VCEs were key examples of this as Elephants Alive!(C) felt they fostered a greater sense of involvement since attendees knew the money they had paid for a ticket directly funded the elephant collaring operation they were participating in virtually.

Marketing was the most frequently discussed benefit by 80% of respondents (). In particular, Game Reserves benefitted from using virtual safaris as a marketing tool to ‘keep the interest going with our [online] followers’ (Lodge A(G)) and to keep ‘the dream of travelling to Africa alive’ (Singita(G)), stimulating the demand for in-person visits after restrictions were eased.

Financially, virtual safaris provided a ‘welcome additional income stream’ (Lodge A(G)) for 70% of respondents (). &Beyond(G) described how ‘virtual safaris went a long way towards supplementing the lost income that normally goes towards conservation and community initiatives’, generating over US$140,000. Respondents were able to pivot to a virtual medium and generate funds to keep their most vital conservation and community initiatives afloat (Kariega(C), DSWF(C)).

Outcomes: challenges

The themes discussed by different categories of respondents was more apparent in relation to describing challenges associated with virtual safaris (). Broadcasters and Conservation Charities both highlighted challenges with ‘engaging with people virtually’ and ‘being live’. All respondents agreed that live virtual safaris offering interactivity were the most beneficial, yet the most difficult to execute. Challenges associated with the technology required for live virtual safaris were reported by 70% of respondents () and WildEarth(B) explained: ‘There’s a myriad [of technical challenges], and they are ongoing.’ Acquiring a communications signal and the cost of operations were the most difficult to overcome. Painteddog.tv(B) agreed that ‘getting the live broadcast on a moving vehicle from the middle of the African bush … is the biggest challenge in virtual safaris’.

Such technical challenges were also the primary barrier for respondents who did not include a live game drive component in their virtual safaris (). Kariega(C) felt that undertaking virtual safaris were ‘not as simple as taking your phone out on a game drive and saying ‘there’s a lion, there’s an elephant’’. Some respondents employed a hybrid approach to overcome barriers, showing a pre-recorded game drive coupled with live interaction with an expert guide ().

Attitudes towards future use

Respondents believed virtual safaris were not replacements for in-person safaris, and were unlikely to compete with conventional forms of tourism in the future. Respondents did, however, emphasize the complementary role virtual safaris could have as a ‘very large and essentially effective add-on’ (Painteddog.tv(B)). In relation to in-person tourism, DSWF(C) explained:

I do think it [virtual safaris] has a place. If you try and compare one with the other it is difficult, but I think if you look at it as a new initiative to engage new people in a new way, then I think it can bring a lot to the table.

VNBT and tourism: conservation resilience

Beyond discussion on virtual safaris, impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic shifted how respondents viewed the relationship between conservation and the tourism industry. While respondents repeatedly acknowledged tourism as an important revenue stream for conservation, actions to ease the reliance on tourism were discussed critically by almost all respondents, for example: ‘There needs to be a broader look at how you can sustainably fund these [conservation and community] projects’ DSWF(C), and ‘Ecotourism is really important, none of us can survive without it, but actually, the funding of the bigger conservation picture also needs to come from other sources’ Kariega(C). Suggestions for enhancing conservation resilience included income diversification beyond tourism (DSWF(C)), collaborative efforts between landowners by dropping fences and combining resources (Kariega(C)), and greater inclusion and appreciation of nature in daily life (WildEarth(B)). VNBT is clearly only part of the possible solutions.

Discussion

Although virtual safaris existed prior to the pandemic, their popularity soared in the wake of COVID-19, with conservation operators adopting them as a ‘new technology product’ (Giddy & Rogerson, Citation2021, p. 703) out of necessity to fund or support conservation initiatives. The nascent virtual safari ‘industry’, and the multitude of different approaches reported by this study indicated a need to create definitions to aid uptake by conservation operators. Indeed, a lack of consensus in the literature and among practitioners about the definition of ‘virtual tourism’ or ‘virtual experiences of nature’ (Cho et al., Citation2002; Mura et al., Citation2017) contributes to the difficulty of defining virtual safaris and deciding how to communicate the differences among disparate approaches. Given that the digitalization of the tourism industry is expected to accelerate (OECD, Citation2020), precise definitions are required to support investment into this ‘new industry’.

The use of virtual safaris and the outcomes for conservation operators

Live-streaming and interactivity were emphasized as essential attributes for conveying authenticity and the findings supported other studies analysing new digital trends during COVID-19 (Glenn, Citation2021; Jarratt, Citation2020; Turnbull et al., Citation2020). Importantly, attending a live virtual safari ‘demands ‘being there’’ (Turnbull et al., Citation2020, p. 6.8) as the event is taking place. The commitment to ‘being there’ facilitates a greater sense of connection for viewers (Jarratt, Citation2020) and for conservation operators who reported they felt connection, solidarity, and encouragement from live events (Elephants Alive!(C), Kariega(C), AWF(C)). Given the value attached to authenticity in live virtual safaris by respondents, these should not be conflated with other forms of VNBT. Although highly beneficial, significant challenges associated with acquiring signal and technical equipment meant that not all respondents could utilize live virtual safaris. The technical challenges represented major barriers to accessing this form of VNBT, limiting use by conservation operators despite being the most productive approach to virtual safaris.

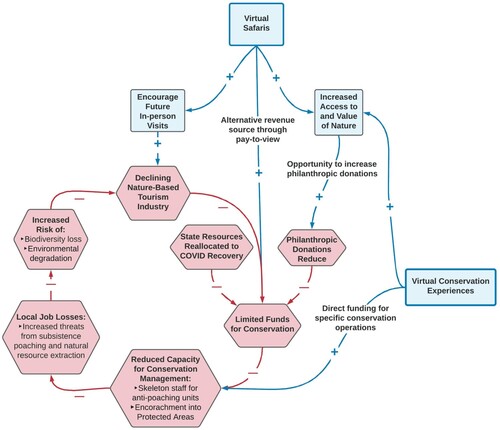

Conservation operators employed virtual safaris as a new tool in distinct ways. illustrates an overview of the utility of virtual safaris and VCEs in response to the impacts of the pandemic on conservation funding. Three mechanisms through which virtual safaris helped to alleviate the effects of COVID-19 are conceptualized.

Figure 2. The role of virtual safaris and virtual conservation experiences (blue squares) in alleviating the negative impacts of COVID-19 on the conservation-tourism relationship from (red hexagons).

A stopgap measure

Game Reserves and Conservation Charities predominantly used virtual safaris as an interim solution to the sudden reduction in funding typically provided by tourism. Pay-to-view private virtual safaris were an ‘important revenue stream’ (&Beyond(G)) for maintaining critical conservation and community projects () and provided a new means for Conservation Charities to engage with donors. Conversely, free-to-view public virtual safaris served primarily as a marketing tool to enable Game Reserves to remain ‘relevant’ while lockdowns impeded tourism. By reaching a wide audience with their stories from the African bush, they incited interest in future physical visitation, which then translated into bookings. This study supported previous research which has shown virtual visitation of locations increases the likelihood of physical visitation (Akhtar et al., Citation2021; Jarratt, Citation2020; Mura et al., Citation2017). In the short term, virtual safaris contributed to conservation resilience by helping to alleviate the impacts of funding deficits and assisted with business recovery.

Revenue diversification

The impacts of COVID-19 have reignited discussion about the critical need to diversify conservation funding (Cumming et al., Citation2021; Lindsey et al., Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2021) and tourism products (OECD, Citation2020) to support the long-term resilience of conservation. However, within these discussions there has been scant mention of VNBT. This study shows that virtual safaris and VCEs may provide an avenue to reduce the reliance of conservation in sub-Saharan Africa on the conventional tourism sector. Most (70%) respondents reported that virtual safaris provided a valuable alternative revenue source either directly through pay-to-view access or indirectly through stimulating philanthropic donations (). Additionally, virtual safaris as a form of VNBT opened a new space for conservation operators to cultivate wider visitation (Skibins & Sharp, Citation2018), increase the accessibility of nature (Filter et al., Citation2020), improve their relationships with donors (Kariega(C), AWF(C), DSWF(C)), and enhance the value of nature to more people (WildEarth(B)). The novel initiatives produced new configurations of actors as partnerships developed between Broadcasters, Conservation Charities, and Game Reserves () to deliver pioneering virtual safaris and VCEs, which provided revenue that otherwise would not have been received during the COVID-19 restrictions. In this sense, virtual safaris provided both short-term relief and could ultimately lead to increasing the long-term resilience of conservation by being an accessible revenue source that is less vulnerable to stochastic events.

Scaling ecosystem services

Increasing access to nature was a key benefit of virtual safaris (), fostering and strengthening connections between people and nature. While most other respondents focused on the value of virtual safaris for directly sustaining conservation efforts, WildEarth(B) were unique in framing their approach as scaling people’s access to ecosystem services and the benefits of nature. Being present in nature provides many benefits for health and wellbeing (Hartig et al., Citation2011), and studies have shown that virtual nature experiences can elicit similar benefits (Reynolds et al., Citation2020; Tanja-Dijkstra et al., Citation2018). Used as a tool for scaling ecosystem services, virtual safaris could also contribute towards Target 12 of the Convention on Biological Diversity 2030 action targets which aims to ‘increase the area of, access to, and benefits from green and blue spaces, for human health and wellbeing in urban areas and other densely populated areas’ (CBD, Citation2021, p. 7). Furthermore, increasing people’s value of nature is important for fostering conservation values, attitudes, and behaviours (Cumming et al., Citation2021). Virtual safaris could therefore contribute to conservation indirectly by helping to increase the inherent value of nature to a much larger audience through authentic experiences and meaningful engagement.

Zooming ahead: how can VNBT contribute toward conservation going forward?

The different uses of virtual safaris as a stopgap measure, for revenue diversification, and for scaling ecosystem services during the pandemic have demonstrated a ‘proof of concept’ (Painteddog.tv(B)) for their utility going forward. While joining others in recognizing that virtual tourism is not a replacement for conventional tourism (Filter et al., Citation2020; Mura et al., Citation2017), this study has shown that it can effectively act as a proxy during mobility restrictions (Fennell, Citation2021). These findings align with previous studies whereby virtual tourism provides a way to increase the resilience of the tourism industry by digitizing and diversifying products to become less reliant on in-person visitation (Cumming et al., Citation2021; Spenceley et al., Citation2021). VNBT also shows promise for improving the sustainability of tourism in the context of climate change (Lu et al., Citation2021). Virtual safaris can provide visitors with an opportunity to experience the African bush without the intensive carbon emissions associated with travel and the deleterious impacts of tourist congestion.

While virtual safaris helped alleviate some of the funding deficit associated with COVID-19, intervening at particular points in the cycle (), they cannot provide the same support for local livelihoods that rely on income from in-person tourists. VNBT does not benefit all stakeholders in the same way conventional tourism can. That being said, in addition to their use for revenue generation, virtual safaris also have a significant role to play in communicating the intrinsic value of nature and conservation efforts to a much larger audience than those who could experience a safari in person. As a result, virtual safaris ‘brings in an entirely new dimension’ (DSWF(C)) to the way conservation operators can engage with people, which may contribute to conservation resilience in the long-term through broader shifts in the public’s care and value of nature.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been proclaimed as ‘a unique window of opportunity to push for deeper change’ (Sandbrook et al., Citation2020, p. 5) and to challenge the current conservation model. These sentiments are echoed by conservation operators calling for a loosening of the ‘really tight thread’ (AWF(C)) between conservation and tourism. Brockington and Duffy (Citation2010) have previously highlighted the problematic nature of the ‘relentlessly positive’ (p. 481) rhetoric that ‘tourism offers a neat solution to conservation’s problems’ (p. 478). Not for the first time, this reliance on a ‘fickle industry’ (Igoe & Brockington, Citation2007, p. 443), which is highly susceptible to economic and political fluctuations, has been exposed for its shortcomings in ensuring conservation funding. While providing some relief, the solutions offered by forms of VNBT are hardly the departure from the prevailing approaches some have called for. Against this backdrop, the emergence of virtual safaris as a ‘solution’ to the crisis reinforces the continued dependence of conservation on tourism. While more transformative change, such as less reliance on tourism to financially support conservation, should remain a priority for conservationists, given the vulnerabilities inherent in this model, this change is likely to take significant time and effort to enact (Fletcher et al., Citation2020). In the meantime, VNBT can enable conservation operators to maintain their operations through the volatility of the tourism industry, especially if the lessons learnt on collaboration continue.

Conclusion

Practical implications

Virtual safaris have been highly beneficial for providing an alternative revenue source, showcasing wildlife to encourage future visitation, and demonstrating to donors the effects of their support. These benefits served as a vital stopgap measure to support conservation operators through COVID-19 lockdowns and assist with recovery as restrictions changed or eased. Conservation operators expressed their optimism that virtual safaris could provide long-term opportunities for conservation in a new virtual space by allowing people to (virtually) engage, participate, and contribute. Maintaining a ‘live’ presence was an important element for creating connections between viewers and conservationists. However, practically, live virtual safaris and VCEs were the most challenging to undertake due to significant technical difficulties with acquiring a signal from a moving vehicle in the African bush.

Theoretical implications

In the context of mounting calls to diversify conservation funding from sources other than tourism, virtual safaris have essentially created an alternative form of tourism, and in this sense, reinforced the prevailing conservation-tourism relationship through the provision of a new tourism ‘product’. This critique notwithstanding, thinking beyond the more neoliberal discourse of new tourism products, live virtual safaris increase people’s access to nature by promoting a feeling of telepresence which could be beneficial for the wellbeing of viewers who otherwise have limited access to natural environments.

Future research

This study presented an initial analysis of how a collection of different conservation operators experienced the use of virtual safaris. There is a wide scope for research to build upon this preliminary study, especially within other specific areas of VNBT such as virtual interactive wildlife or nature viewing tours outside of sub-Saharan Africa. Studies are needed to explore participants’ experiences of virtual safaris to determine if their attendance led to donations, feelings of authenticity, and a sense of connection to nature and the conservationists. Such studies could also capture the influence VNBT has on behavioural change in the form of pro-environmental attitudes and actions (Hofman et al., Citation2022), especially for those unable to experience in-person safaris due to personal limitations, which could be compared to attitude changes amongst those who experience in-person safaris. Additionally, longitudinal research could track the trajectory of virtual safaris to explore changing patterns in their use and popularity over time. This research could be coupled with studies assessing the contribution of virtual safaris, and VNBT more broadly, to sustainable tourism by providing alternatives to carbon-intensive travel.

Bringing nature into people’s homes via virtual safaris and VCEs has proven to be a valuable tool for conservation. However, it is clear that there is both a need and desire to move beyond the problematic relationship with tourism and search for solutions that make conservation, not only the tourism industry, more resilient.

RCIT_2132921_Appendix_Material

Download Zip (76.5 KB)Acknowledgements

Many thanks are owed to the conservation organizations who spared their time to contribute to this study: African Wildlife Foundation, &Beyond, David Shepard Wildlife Foundation, Elephants Alive!, Kariega Foundation, Painteddog.tv, Singita, WildEarth, and the game lodges and reserves.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Steuer (Citation1992, p. 36) defines telepresence as the ‘experience of presence in an environment by means of a communication medium’.

References

- Akhtar, N., Khan, N., Mahroof Khan, M., Ashraf, S., Hashmi, M. S., Khan, M. M., & Hishan, S. S. (2021). Post-COVID 19 tourism: Will digital tourism replace mass tourism? Sustainability, 13, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105352

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brockington, D., & Duffy, R. (2010). Capitalism and conservation: The production and reproduction of biodiversity conservation. Antipode, 42(3), 469–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2010.00760.x

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Büscher, B., Sullivan, S., Neves, K., Igoe, J., & Brockington, D. (2012). Towards a synthesized critique of neoliberal biodiversity conservation. Capitalism, Nature, Socialism, 23(2), 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2012.674149

- Cho, Y. H., Wang, Y., & Fesenmaier, D. R. (2002). Searching for experiences: The web-based virtual tour in tourism marketing. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 12(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v12n04_01

- Corlett, R. T., Primack, R. B., Devictor, V., Maas, B., Goswami, V. R., Bates, A. E., Koh, L. P., Regan, T. J., Loyola, R., Pakeman, R. J., Cumming, G. S., Pidgeon, A., Johns, D., & Roth, R. (2020). Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation, 246, 8–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108571

- Cumming, T., Seidl, A., Emerton, L., Spenceley, A., Kroner, R. G., Uwineza, Y., & van Zyl, H. (2021). Building sustainable finance for resilient protected and conserved areas: Lessons from COVID-19. Parks, 27(27), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2021.PARKS-27-SITC.en

- Department of Tourism, & Tourism Business Council (TBCSA). (2020). Tourism industry survey of South Africa: COVID-19 impact, mitigation and the future. Department of Tourism. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/648261588959603840/pdf/Tourism-Industry-Survey-of-South-Africa-COVID-19-Impact-Mitigation-and-the-Future-Survey-1.pdf.

- Fennell, D. A. (2021). Technology and the sustainable tourist in the new age of disruption. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(5), 767–773. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1769639

- Filter, E., Eckes, A., Fiebelkorn, F., & Büssing, A. G. (2020). Virtual reality nature experiences involving wolves on YouTube: Presence, emotions, and attitudes in immersive and nonimmersive settings. Sustainability, 12(9), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093823

- Fletcher, R., Büscher, B., Massarella, K., & Koot, S. (2020). Close the tap!’: COVID-19 and the need for convivial conservation. Journal of Australian Political Economy, 85, 200–211. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.213459337360391

- Gibbons, D. W., Sandbrook, C., Sutherland, W. J., Akter, R., Bradbury, R., Broad, S., Clements, A., Crick, H. Q., Elliott, J., Gyeltshen, N., & Heath, M. (2021). The relative importance of COVID-19 pandemic impacts on biodiversity conservation globally. Conservation Biology, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.13781

- Giddy, J. K., & Rogerson, J. M. (2021). Nature-based tourism enterprise adaptive responses to COVID-19 in South Africa. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 36(2spl), 698–707. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.362spl18-700

- Glenn, I. (2021). Telesafaris, WildEarth television, and the future of tourism. International Journal of Communication, 15, 2569–2585.

- Globetrender. (2020). AndBeyond sells live online safaris to fund conservation. https://globetrender.com/2020/12/09/andbeyond-private-virtual-safaris-conservation/.

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1758708

- Gretzel, U., Fuchs, M., Baggio, R., Hoepken, W., Law, R., Neidhardt, J., Pesonen, J., Zanker, M., & Xiang, Z. (2020). e-Tourism beyond COVID-19: A call for transformative research. Information Technology and Tourism, 22(2), 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-020-00181-3

- Hartig, T., van den Berg, A. E., Hagerhall, C. M., Tomalak, M., Bauer, N., Hansmann, R., Ojala, A., Syngollitou, E., Carrus, G., van Herzele, A., Bell, S., Podesta, M. T. C., & Waaseth, G. (2011). Health benefits of nature experience: Psychological, social and cultural processes. In K. Nilsson, M. Sangster, C. Gallis, T. Hartig, S. de Vries, K. Seeland, & J. Schipperijn (Eds.), Forests, trees and human health (pp. 127–168). Springer Netherlands.

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. (2020). Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 610–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1757748

- Hockings, M., Dudley, N., Elliott, W., Ferreira, M. N., MacKinnon, K., Pasha, M., Phillips, A., & Stolton, S. (2020). Editorial essay: COVID-19 and protected and conserved areas. Parks, 26(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2020.PARKS-26-1MH.en

- Hofman, K., Hughes, K., Hofman, K., Hughes, K., & Walters, G. (2022). The effectiveness of virtual vs real-life marine tourism experiences in encouraging conservation behaviour. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(4), 742–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1884690

- Igoe, J., & Brockington, D. (2007). Neoliberal conservation: A brief introduction. Conservation and Society, 5(4), 432–449. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26392898

- Jarratt, D. (2020). An exploration of webcam-travel: Connecting to place and nature through webcams during the COVID-19 lockdown of 2020. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 21(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358420963370

- Kideghesho, J. R., Kimaro, H. S., Mayengo, G., & Kisingo, A. W. (2021). Will Tanzania’s wildlife sector survive the COVID-19 pandemic? Tropical Conservation Science, 14), https://doi.org/10.1177/19400829211012682

- Kroner, R. G., Barbier, E. B., Chassot, O., Chaudhary, S., Cordova, L., Cruz-Trinidad, A., Cumming, T., Howard, J., Said, C. K., Kun, Z., Ogena, A., Palla, F., Valiente, R. S., Troëng, S., Valverde, A., Wijethunga, R., & Wong, M. (2021). COVID-era policies and economic recovery plans: Are governments building back better for protected and conserved areas? Parks, 27(27), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2021.PARKS-27-SIRGK.en

- Lendelvo, S., Pinto, M., & Sullivan, S. (2020). A perfect storm? The impact of COVID-19 on community-based conservation in Namibia. Namibian Journal of Environment, 4(2018), 1–15. http://www.nje.org.na/index.php/nje/article/view/volume4-lendelvo

- Leung, Y., Spenceley, A., Hvenegaard, G., Buckley, R., & Groves, C. (2018). Tourism and visitor management in protected areas: Guidelines for sustainability (Issue Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 27).

- Lindsey, P., Allan, J., Brehony, P., Dickman, A., Robson, A., Begg, C., Bhammar, H., Blanken, L., Breuer, T., Fitzgerald, K., & Flyman, M. (2020). Conserving Africa’s wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 4(10), 1300–1310. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6

- Lu, J., Xiao, X., Xu, Z., Wang, C., Zhang, M., & Zhou, Y. (2021). The potential of virtual tourism in the recovery of tourism industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1959526

- Moon, K., & Blackman, D. (2014). A guide to understanding social science research for natural scientists. Conservation Biology, 28(5), 1167–1177. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12326

- Mura, P., Tavakoli, R., & Pahlevan Sharif, S. (2017). Authentic but not too much’: Exploring perceptions of authenticity of virtual tourism. Information Technology and Tourism, 17(2), 145–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-016-0059-y

- Newing, H., Eagle, C., Puri, R., & Watson, C. (2010). Conducting research in conservation: Social science methods and practice. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). Rebuilding tourism for the future: COVID-19 policy responses and recovery. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=137_137392-qsvjt75vnh&title=Rebuilding-tourism-for-the-future-COVID-19-policy-response-and-recovery&_ga=2.248143239.105579590.1623153762-1095069542.1623153762.

- QSR International. (2020). NVivo qualitative data analysis software.

- Reynolds, L., Rogers, O., Benford, A., Ingwaldson, A., Vu, B., Holstege, T., & Alvarado, K. (2020). Virtual nature as an intervention for reducing stress and improving mood in people with substance Use disorder. Journal of Addiction, 2020, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1892390

- Sandbrook, C., Gómez-Baggethun, E., & Adams, W. M. (2020). Biodiversity conservation in a post-COVID-19 economy. Oryx, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605320001039

- Searle, A., Turnbull, J., & Lorimer, J. (2021). After the anthropause: Lockdown lessons for more-than-human geographies. Geographical Journal, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12373

- Skibins, J. C., & Sharp, R. L. (2018). Binge watching bears: Efficacy of real vs. Virtual flagship exposure. Journal of Ecotourism, 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2018.1553977

- Smith, M. K. S., Smit, I. P. J., Swemmer, L. K., Mokhatla, M. M., Freitag, S., Roux, D. J., & Dziba, L. (2021). Sustainability of protected areas: Vulnerabilities and opportunities as revealed by COVID-19 in a national park management agency. Biological Conservation, 255, 108985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2021.108985

- Spenceley, A., McCool, S., Newsome, D., Báez, A., Barborak, J. R., Blye, C. J., Bricker, K., Sigit Cahyadi, H., Corrigan, K., Halpenny, E., & Hvenegaard, G. (2021). Tourism in protected and conserved areas amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Parks, 27(27), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2021.PARKS-27-SIAS.en

- Steuer, J. (1992). Defining virtual reality: Dimensions determining telepresence. Journal of Communications, 42(4), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1992.tb00812.x

- Sullivan, S. (2006). Elephant in the room? Problematising ‘new’ (neoliberal) biodiversity conservation. Forum for Development Studies, 33(1), 105–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2006.9666337

- Tanja-Dijkstra, K., Pahl, S., White, M. P., Auvray, M., Stone, R. J., Andrade, J., May, J., Mills, I., & Moles, D. R. (2018). The soothing sea: A virtual coastal walk can reduce experienced and recollected pain. Environment and Behavior, 50(6), 599–625. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916517710077

- Turnbull, J., Searle, A., & Adams, W. M. (2020). Quarantine encounters with digital animals: More-than-human geographies of lockdown life. Journal of Environmental Media, 1(1), 6.1–6.10. https://doi.org/10.1386/jem_00027_1

- United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). (2021). First draft of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework. https://www.cbd.int/doc/c/abb5/591f/2e46096d3f0330b08ce87a45/wg2020-03-03-en.pdf.

- United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO). (2021). UNWTO World Tourism barometer and statistical annex, May 2021. https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/abs/10.18111wtobarometereng.2021.19.1.3.

- Valentine, G. (2005). Tell me about … : Using interviews as a research methodology. In R. Flowerdew, & D. M. Martin (Eds.), Methods in human geography: A guide for students doing a research project, Second Edi, (pp. 110–128). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Verkerk, V.-A. (2022). Virtual reality: Saving tourism in South Africa? African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure, 11(1), 278–293. https://doi.org/10.46222/ajhtl.19770720.225

- Waithaka, J., Dudley, N., Álvarez Malvido, M., Mora, S. A., Chapman, S., Figgis, P., Fitzsimons, J., Gallon, S., Gray, T. N. E., Kim, M., Pasha, M. K. S., Perkin, S., Roig-Boixeda, P., Sierra, C., Valverde, A., & Wong, M. (2021). Impacts of COVID-19 on protected and conserved areas: A global overview and regional perspectives. Parks, 27(27), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.CH.2021.PARKS-27-SIJW.en

- World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC). (2019). The economic impact of global wildlife tourism. https://travesiasdigital.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/The-Economic-Impact-of-Global-Wildlife-Tourism-Final-19.pdf.