ABSTRACT

Blockchain could disrupt traditional accommodation services by enabling safe, decentralised direct connections between guests and hosts. However, how users will accept and use blockchain-based services in tourism and hospitality remains unascertained. This study explores users’ perceptions of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system and sets a theoretical basis to conceptualise the drivers of the acceptability of such a system. By using a grounded theory approach involving theoretical sampling and three steps of coding and constant comparison procedures, this study revealed that users were drawn to the system because it delivers desirable characteristics that are absent from existing services, such as further reduction of transaction fees, instant transaction settlement, wider income distribution, data integrity, algorithm autonomy, and smart protocol. Personal and social contexts were also found to influence users’ preferences for blockchain type and system ownership models. By offering key predictors and a theoretical model of user acceptance of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system, hence taking a bottom-up approach to complement the highly top-down extant literature, this paper allows stakeholders exploring the use of blockchain technology in the tourism and hospitality sectors to have a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon.

Introduction

The modern sharing economy is distinguished by its platform-based business model. It allows platform providers to scale rapidly without needing huge assets or many personnel, making them one of the global economy's pillars (PwC, Citation2015). From a user's point of view, this model adds more value than traditional exchange mechanisms. Airbnb, for example, creates an opportunity for those who own idle property to earn additional income (Narasimhan et al., Citation2018). Simultaneously, its 5.6 million listings (Airbnb, Citation2021a) give more alternatives for travellers needing accommodation. However, crowd-generated value is not evenly dispersed across all participants in the existing platform-based model. Instead, platform operators (often referred to as ‘platform capitalists’) absorb most of the economic rewards as they can collect fees for their services and commodify users’ personal and transaction data for profit-making purposes (Langley & Leyshon, Citation2017). Consequently, platform capitalists have vast data control and market knowledge, making them more powerful than traditional capitalists.

To that end, the blockchain has recently emerged, offering the potential to reshape existing services. It facilitates value exchange and app operation in a decentralised manner; allowing instant transaction settlement, traceability, and transparency in hospitality operations (Filimonau & Naumova, Citation2020). Furthermore, the blockchain can automate trust, enable working autonomy, and facilitate hyperconnected networks (PwC, Citation2020). Therefore, integrating blockchain into a peer-to-peer accommodation system will enable guests and hosts to engage in direct online transactions using a secure, inexpensive, and globally connected platform.

Although the concept offers much potential, whether users will adopt such a novel system in tourism and hospitality remains an important research question. Existing research primarily focuses on technological aspects with top-down standpoints that are more pertinent to developers or technology providers. Users’ perceptions of such a concept have received little attention, despite being critical for fostering adoption. Indeed, Önder and Gunter (Citation2022) call for more research on user-centric blockchain innovation. This study thus aims to contribute to the literature on the adoption and use of blockchain within tourism and hospitality by filling this critical research gap, supplementing existing top-down knowledge with the users’ perspective, and providing a theoretical model of user acceptance of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system.

The next section synthesises the relevant literature on the sharing economy, blockchain, and technology adoption. This is followed by the methodology, findings, and discussion. The conclusions and implications wrap up the study.

Literature review

Platform capitalism

The modern sharing economy utilises the internet (Belk, Citation2014) and mobile applications (Narasimhan et al., Citation2018). Its main characteristic is the presence of intermediaries (Narasimhan et al., Citation2018), which facilitate the interaction between strangers (Belk, Citation2014; Schor & Fitzmaurice, Citation2015). It enables the exchange of goods and services and social networking (Schor & Fitzmaurice, Citation2015).

Economically speaking, a platform-based sharing economy facilitates cheaper access to goods and services (Acquier et al., Citation2017; Narasimhan et al., Citation2016). It enables the utilisation of idle assets (Narasimhan et al., Citation2018). For example, Airbnb allows individual property owners, regardless of the type or size of the property, to offer an attractive alternative accommodation to travellers. Furthermore, it multiplies beneficiaries (Murillo et al., Citation2017), evolving two-party activity into three-party activity (Narasimhan et al., Citation2018).

The platform-based sharing economy also strengthens the social aspect of commercial transactions (Schor & Fitzmaurice, Citation2015). It enables social connections between providers of goods or services and their users (Tussyadiah, Citation2015; Tussyadiah & Pesonen, Citation2016; Citation2018). It also plays a vital role in community empowerment (Schor, Citation2016) and can initiate cross-industry collaboration (Puschmann & Alt, Citation2016).

Regrettably, the platform-based sharing economy has deviated from its initial vision (Schor & Fitzmaurice, Citation2015). Limited transparency exists (Lecuyer et al., Citation2017), and its centralised business model often leads to platform capitalism (Langley & Leyshon, Citation2017). Blockchain, ergo, stands a chance to provide solutions to the deficiencies of current platform-based systems.

Blockchain and disintermediation in the accommodation rental market

Blockchain is a deterministic (Al-Kuwari et al., Citation2011), one-way (Charles et al., Citation2009), and irreversible (Underwood, Citation2016) method of storing data in interconnected digital blocks (Nakamoto, Citation2008). It protects data from fraud, as attackers would need to change data on all blocks in all users before a new block is created. Blockchain and its cryptography also prevent double-spending (a transaction is recorded more than once due to malicious behaviour or error), solving the core problem of digital transactions without intermediaries (Nakamoto, Citation2008).

Buterin (Citation2014) then expanded on this concept in the Ethereum project, which introduced blockchain-based smart contracts, creating the capability for apps to operate in a decentralised way. Such a system runs through an electronic protocol that automatically executes a contract based on predetermined triggers (Szabo, Citation1994). It thus offers a highly secure autonomous hub that can automate trust (PwC, Citation2020). It eliminates centralised intermediaries, minimises transaction costs, and reduces conflict of interest (Khan & Ouaich, Citation2019).

Blockchain systems can be public or private (Casino et al., Citation2019); however, a public blockchain may be preferable in the case of a peer-to-peer accommodation system since all users become shareholders of the network. Choosing a private blockchain means system ownership and authority remain with certain parties. In terms of usage, a blockchain system's access rights mechanism can be permissionless, i.e. the system is open to anyone, or permissioned, i.e. usage is restricted to those who have been granted access rights (Golosova & Romanovs, Citation2018).

It is argued that blockchain-based smart contracts could bring the next level of disintermediation in the accommodation rental market. It removes the need for middlemen such as Airbnb or an online travel agency (OTA) and improves host–guest relationships through better transparency and secure mechanisms (Filimonau & Naumova, Citation2020). Further investigation is required to do a reality check on the prospects of such a concept versus the actual interest of its potential users.

Blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation

Existing studies on blockchain that relate to peer-to-peer accommodation are scant. Of the few that exist, most chose a top-down approach, exploring issues that are more relevant to developers or technology service providers than to users. One of the prevalent topics on blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation covered in existing research is the complexities of dealing with privacy concerns. Resolving privacy issues in blockchain-based two-way transactions, such as accommodation renting, is more complicated than in one-way transactions, such as cryptocurrency transfers (Xu et al., Citation2017). A trade-off must be managed between protecting the privacy and ensuring the legitimacy of transaction actors. Therefore, proper identity management is critical because it instils the basis for trust (Kundu, Citation2019).

Privacy concerns extend beyond protecting personal and transaction data to covering off-chain behaviours. For example, Islam and Kundu (Citation2018) proposed using blockchain to incorporate dynamic encryption keys in internet protocol (IP) cameras in the rental property to prevent the host from engaging in illegal surveillance activity. While guests are staying in the rented property, the host's access to the IP camera can be disabled; and because it is tied to the blockchain, the host cannot manipulate the access rights mechanism.

Beyond privacy, Jacquemin (Citation2019) demonstrates how a blockchain smart contract might arbitrate disputes in sharing economy services. If a host–guest dispute arises, factual data on transactions and accommodation usage that were collected via blockchain-connected IoT devices can be used to enforce the contract automatically. However, dealing with disagreements that the system cannot handle is a subject that has yet to be addressed in the extant literature.

Also worth noting is the potential application of blockchain in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nowadays, traceability is vital (Pandey & Pal, Citation2020). The high auditability of blockchain-based systems in addressing who, what, and when (Huckle et al., Citation2016; Kundu, Citation2019; Li et al., Citation2018; Niranjanamurthy et al., Citation2019) may be used to guarantee the cleanliness of the property (e.g. by using a sensory device that is connected to a blockchain). Furthermore, the concept of a blockchain-based smart lock that enables a secure self-check-in / self-check-out procedure, as mentioned by Kundu (Citation2019), could be utilised to reduce physical contact between hosts and guests.

To summarise, besides a general paucity of research in this area, extant research on blockchain that relates to peer-to-peer accommodation has mainly focused on the technological aspects, discussing concerns from the standpoint of system developers or platform providers. This topic has rarely been studied from the end users’ perspective. Therefore, exploring this dimension can help in developing a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system that is feasible and acceptable to users while also adding to the knowledge base of existing research on this subject.

Technology acceptance

Numerous major theoretical models explain technology acceptance from the users’ perspectives. Among the most influential are the technology acceptance model (TAM) (Davis, Citation1989; Davis et al., Citation1989) and its extended versions, TAM2 (Venkatesh, Citation2000; Venkatesh & Davis, Citation2000), the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Venkatesh et al., Citation2003), and UTAUT2 (Venkatesh et al., Citation2012). TAM offers a rather simplistic explanation of user acceptance, making the model applicable in various contexts. However, this theoretical simplicity was posited to be a source of its drawbacks. In most circumstances, users’ decision to choose a certain technology exceeds considerations of usefulness and ease of use (Lunceford, Citation2009). Focusing on these constructs alone can lead to researchers missing other critical aspects of technology acceptance (Benbasat & Barki, Citation2007) and thus render the results lacking in practical value (Chuttur, Citation2009).

This study intends to capture specific characteristics of blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation and the social dynamics that affect users’ acceptance of such a system. Constructs such as ease-of-use and usefulness will not be applicable in this context due to the system's novelty and will fail to capture the intricacies around preferences and perceived value of such a system. For these reasons, existing technology acceptance models were considered unsuitable for this study and, therefore, constructing a new model was deemed necessary.

Methods

This study uses a grounded theory approach to identify the predictors of users’ acceptance of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system. The grounded theory allows flexibility in rationalising behaviour (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1965); it seeks to dispel preconceptions and see things as they truly are (Glaser, Citation2014). This method enabled gathering of users’ viewpoints on a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system and the dynamics contributing to preference discrepancies. Grounded theory research typically produces a theory, model, or in-depth description (Wiesche et al., Citation2017). This study produces a model of user acceptance of blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation.

For data collection, focus group discussions (FGDs) were preferred over individual interviews since the topic was still relatively new. Through FGDs, participants exchanged ideas, sparking new concepts relating to the theme, and conducted a collective sensemaking process (Wilkinson, Citation1998). This technique also ensured that participants drove the meaning-making process (Reybold et al., Citation2013).

A semi-structured format is used to limit out-of-context conversations. The FGDs revolved around the following themes: (a) thoughts/opinions about the existing peer-to-peer accommodation system and areas for change and/or improvement, (b) opinions and thoughts about blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation, (c) participants’ intention to participate in such a system. FGD questions were reviewed by three experts on the topic, drawn from academia and industry. The FGD guide can be found in Appendix 1.

Six FGDs were conducted. The number of participants varied from 3 to 10 in each FGD, making up a total of 30 participants. The FGDs and transcription data processing took place from October 2020 to February 2021. Each FGD lasted about 90 min. The FGDs were conducted online using a video conferencing application, Zoom, due to the Covid-19 pandemic and applicable public health guidelines that limited face-to-face contact. Reid and Reid (Citation2005) showed no difference in decision quality between online and offline FGDs; the online method is even said to generate significantly more new ideas.

Participants were selected based on theoretical sampling (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990). The initial inclusion criteria included familiarity with Airbnb and a basic understanding of blockchain. The theoretical sampling was then adjusted as the research advanced to expand, confirm, and deepen the ideas and concepts gathered from prior FGD sessions. The inclusion criteria for the latest two FGDs centred on substantive exposure to the blockchain (i.e. participants have used blockchain-based services or studied blockchain-related knowledge).

Each participant chose an FGD session based on their availability; thus, the authors could not manipulate the discussion by grouping people with similar characteristics. They were invited via email through the institution where the authors are affiliated. Participants were academics, professionals, and postgraduate students from the services and other relevant sectors (i.e. Tourism and Hospitality, Business Management, Information Technology, Computer Science, and Engineering). Participants were also of diverse nationalities and ethnicities (African, American, Asian, and European). The gender distribution of participants was 16 women and 14 men.Footnote1

Data analysis, coding, and theoretical model development

Data analysis was performed simultaneously with the coding process, following the three steps suggested by Wiesche et al. (Citation2017). These coding stages also constitute the three steps constant comparative procedures of this study (see Appendix 2), which was adapted from Boeije (Citation2002). The first step was open coding, which involved extensively reading, comparing, and labelling each focus group's transcripts. The second step was axial coding to conceptualise and produce the provisional typology; this included comparisons between FGDs to reveal patterns. At this stage, the authors held several discussions to get a consensus on major themes. The third step was theoretical coding, which included a comprehensive comparison and final consensus on interpretation. The results were then developed into a user acceptance model of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system. Once the theoretical model was obtained, the last stage was consulting with relevant literature (Charmaz, Citation1996). This final stage was not intended to confirm or add to the preceding stages’ results but to polish the articulation of the obtained concepts (Gioia et al., Citation2013).

To ensure that the final model accurately reflects the participants’ perspectives, member checks were conducted in the manner described by Tuomi et al. (Citation2021). Several participants were given the final model, and all agreed that it accurately reflected the FGD results.

Findings and discussion

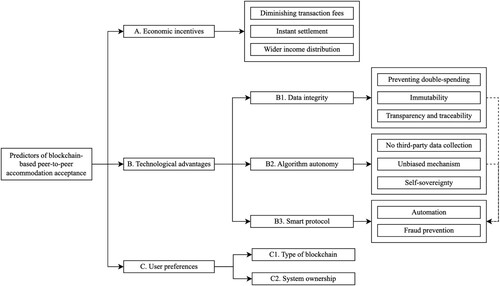

The analysis revealed three groups of key predictors of acceptance of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system. These are [A] economic incentives, [B] technological advantages (which have three lower-level codes: [B1] data integrity, [B2] algorithm autonomy, and [B3] smart protocol), and [C] user preferences (related to [C1] blockchain type and [C2] system ownership) (see ).

Economic incentives

Existing peer-to-peer accommodation services were favoured mainly due to their pricing advantage, as evidenced by the following quotes:

One of the benefits of using the sharing economy is the price itself, which tends to be lower. (FG1-P4).

[Airbnb is] very much more affordable than going to a hotel, and it is usually bigger [and] has more facilities. (FG2-P4).

This study further identified that the use of blockchain was believed to advance economic benefits by further lowering transaction costs, allowing instant transaction settlement, and offering wider income distribution.

Diminishing transaction fees

Blockchain-based transactions are not handled by a centralised intermediary (Babkin et al., Citation2018; Islam & Kundu, Citation2018); this could dramatically lower transaction costs because no service fees are imposed on guests and hosts. Participants indicated that this was a crucial element of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system:

… reducing the fees that [the existing services] are taking [is] the most important thing (FG3-P3).

I think one of the best things is no transaction fees and no currency conversion fees (FG6-P2).

It can be suggested that further cost reduction in a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system will appeal to budget and mid-income-level travellers, especially when due consideration is given to a global economic recession (Campos-Soria et al., Citation2015).

Instant settlement

In a centralised system, transaction settlement could take days due to administrative processes on the intermediary side, which are confined by bureaucracy, working hours, and regulations. A blockchain-based system, however, eliminates the need for an intermediary and uses smart contracts to complete the transaction, allowing for instant transaction settlement (Khan & Ouaich, Citation2019). In such a system, ‘ … there is no broker in between … ’ (FG3-P2). Another participant stated:

I know blockchain. Actually, there is no need for a [centralised] platform, right, so it is [a] peer-to-peer way to do the transaction. (FG4-P3).

It can really start to add up [value] if you travel a lot or if you just buy things from abroad. Whereas if you have one decentralised currency, it does not matter where you are from or where you are going; you can just use [it]. (FG6-P2).

I watched a YouTube video before about a businessman. He created an AI machine [that is connected to a blockchain] to [handle] coffee beans. And so, the farmers can put the coffee beans into the machine and directly get money. [So] the farmers can get money without any [delay that can risk them to] bankruptcy or anything (FG6-P4).

Wider income distribution

While the existing sharing economy transforms two-party activities into three-party activities (Narasimhan et al., Citation2018), the blockchain-based system will turn it into multi-party activities. A central authority that facilitates and manages all exchanges will no longer exist; thus, there is no exclusive beneficiary of transaction fees. All users can contribute (i.e. by being a miner or validator), and they will be rewarded for their contribution. This opportunity could encourage users ‘ … to use more of the service to get more incentives.’ (FG3-P3). Participants viewed this as a necessary and positive change, as evidenced by the following quotes:

But it [has] to benefit more people, like distributed all over the world in order to make it sustainable and run it like properly and fairly. (FG2-P3).

… it is obviously better to not have all that wealth condensed in one entity. … if the fees are then split amongst all the different miners, then it would create less wealth inequality in the long run, … (FG6-P2).

[Income distribution] is very interesting. I am just thinking of the technical aspect because, for now, as you mentioned, the challenges of having those miners on all devices are very computation heavy. (FG5-P7).

Technological advantages

Three sub-themes were identified regarding the technological advantages of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system: data integrity, algorithm autonomy, and smart protocols.

Data integrity

Preventing double spending

One of the prominent features of blockchain is its ability to prevent double-spending (Kundu, Citation2019). Double-spending is a classic problem in electronic commerce where transactions were recorded more than once due to accidental or malicious behaviour. Participants believed that this feature would protect them from technical errors and fraud:

I think it would be nice to have a blockchain and [an integrated] logging system; as someone has mentioned before, sometimes, … the room [was double-booked on a different website]. But if it is blockchain, I am sure there will not be any mistake like that. (FG5-P6).

So you mentioned bitcoin; if we can use that to give an example, you send money to a friend, and tomorrow [you] cannot say that [you] did not do it. … the system has already recorded [it] with your public key, and it was actual value. So, you cannot deny it. (FG6-P1).

Immutability

The blockchain-based sharing economy has an irreversible mechanism, which makes it almost impossible to hack. Participants agreed on the importance of immutability. For example:

I think [immutability] is a great characteristic to have, especially the idea that nobody can change anything, or if you change anything [we] can see it easily. So, that is what reduces any risk associated with that. (FG3-P3).

There is a feature called non-repudiation. So, denying what you have done is impossible. … this is one of the features that blockchain has, so whatever you do, is written. (FG6-P1)

Transparency and traceability

Participants frequently emphasised transparency and traceability expectations, enticing them to blockchain-based systems. As indicated by the following participants:

I would go for it, basically, because the prices are lower. … , and it is more transparent. (FG2-P3)

I will be interested in [it] because there will be greater transparency. (FG6-P4).

Some participants expressed concerns regarding privacy if everything is traceable. However, these might be resolved because the blockchain system allows anonymity (Ferraro et al., Citation2018; Jacquemin, Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2018). As one participant noted:

I think the blockchain works, … . I do not think everyone can see all the transactions we made, but probably everyone can see the traffic of the transaction, but not every single identity of the transaction (FG1-P5).

Algorithm autonomy

No third-party data collection

The commodification of users’ data is one of the key causes of participants’ desire to de-corporate existing services. In a centralised service, once the platform has mastered the data and the market, they tend to forget its initial social goals (Schor & Fitzmaurice, Citation2015), as has been observed with many emerging tech giants that use this business model (Acquier et al., Citation2017). Many participants expressed enthusiasm about how a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system will address this issue. For example, as FG3-P2 put it:

[This system is] limiting the [number] of people that have access to your information because there is no broker in between that receives information, assesses it, and passes it, … so limit the exposure of the data as well. So [it] minimises the risk of data leakage. (FG3-P2).

I like the idea … that the data you provide will not be able to be used by companies. (FG5-P4).

Unbiased mechanism

Another aspect of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system that reflects algorithm autonomy is its unbiased mechanism. It ensures fairness and becomes one of the appealing features for users:

As much as I know, when I heard about some [of] those kinds of [innovations]. [Blockchain-based] platforms are quite trustworthy things. … . So, I would go for it. … . It feels fairer … (FG2-P3)

It is almost like a third-party system that is unbiased and only based on facts and data. (FG4-P2).

Self-sovereignty

Another noteworthy finding was that participants were very enthused about the ability of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system to enable users’ self-sovereignty when engaging in system operations. In this context, self-sovereignty is a form of user empowerment in which users have more control over how their data is used in the system (Kundu, Citation2019; Locher et al., Citation2018; Niranjanamurthy et al., Citation2019; Xiao, Citation2020). Participants agreed on the critical nature of personal data sovereignty. For example:

… the privacy [mechanism] of this system is also important for me because it can make me feel safer using the system. Yeah, and I can see nowadays there are a lot of people. They are afraid to use a new system just because of the integrity and the privacy. (FG3-P1).

It is really interesting that you have some sort of agency and control over [personal] information because it is very private information. (FG4-P2).

Smart protocol

Data integrity and algorithm autonomy allow a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system to employ smart protocols for automation and fraud detection.

Automation

The blockchain-based sharing economy utilises smart contracts to enable automation (Chau et al., Citation2019; Gatteschi et al., Citation2018; Huckle et al., Citation2016; Kundu, Citation2019). Interestingly, participants expressed interest in the future case of automation in blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation beyond automation in booking transactions. They explored ideas of integrating the blockchain with artificial intelligence (AI) and the internet of things (IoT). The complementarity between these emerging technologies brings up a plethora of options which could increase their effectiveness. This, in turn, will positively affect user acceptance (Lian et al., Citation2020).

One suggestion was a sensory device connected to a blockchain system, which may be used to guarantee room cleanliness. This could provide a solution for peer-to-peer accommodation, which is not subjected to the same standards and procedures as hotels. This feature is particularly beneficial, for example, in the COVID-19 pandemic context. As a participant observed:

In the pandemic, when you go to Airbnb, how would you know that things have been cleaned up into places … so knowing [that blockchain-based] sensory things [can track what] has been touched even by previous guests or host would be quite beneficial. (FG5-P1).

Another idea was applying automation for dispute resolution, such as logging the use of facilities in a rented property so that if there is a claim for damage or excessive usage, objective evidence can be obtained for both parties.

So, I think if you could track that kind of information, like how much electricity was being used and then you could change the Airbnb pricing to say, a room costs £50 [per] night, plus £5 [for] electricity and water (FG6-P4).

If you can tie disputes into the legal system … , then I think that is fine. (FG5-P4).

Fraud prevention

Another aspect that was also considered important by the participants was the fraud prevention mechanism. Participants argued that the middlemen in the existing systems did not adequately protect them. One participant (FG2-P4) recounted an experience:

I went to an Airbnb, and then I kind of broke some things, and then, [the host] told me [they will] charge [me], but then I complained to Airbnb, saying that it was like broken before I came there, and [Airbnb] did not do anything. (FG2-P4).

[Blockchain] is good because you can check [the] truth; it is transparent. [The] same thing if someone hacked the system, you could see who did it. (FG3-P2).

User preferences

In addition to economic incentives and technological advantages, participants also expressed their preferred choices regarding blockchain type and system ownership. Participants’ preferences varied, which reflected their differing perspectives toward trust and privacy, the two issues that were also often highlighted in the literature as factors that influence users’ attitudes and behaviour in the sharing economy (Chatterjee et al., Citation2019; Dabbous & Tarhini, Citation2019; Mao et al., Citation2020; Pappas, Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2020; Wu et al., Citation2017; Ye et al., Citation2019).

Type of blockchain

When faced with a choice between a public or private blockchain, most participants favoured a public blockchain. The following FG participants’ statements illustrate this point:

I definitely prefer the [public blockchain], so I prefer everyone being able to contribute equally. (FG4-P2).

I do not like the idea of a single organisation [or] anything controlling it. (FG5-P4).

System ownership

The discussion about the type of blockchain then raised a question about how the system should be regulated. Most participants preferred that a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system should be self-regulated (i.e. with a consensus mechanism), and they opposed a single entity controlling the system. However, few believed that the government should handle such an open system.

More specifically, participants from western countries (i.e. the UK, USA, Israel, and Germany) tended to favour a system that is free from any intervention, including from the government. Examples of arguments from this group included:

Honestly, if it [is] owned and run by the government … I feel like … they already have control over so many things, and I think their agenda does not always align with the agenda of the people, the agenda of the public. (FG4-P2).

You can see that when [a] government starts getting involved … on blockchain and cryptocurrency, that the value like drops. So, they should just be public. It should be left to be done by itself without special interests and big corporations getting involved. (FG6-P2)

I think it is fine, and [most governments and companies] use [our personal data]. … There is no harm, you know, even my personal data. Actually, I know some companies already sell it, so I do not mind. (FG4-P3).

… we do not question a lot about [the] government's decisions that much compared to the Western. And considering this current situation and dynamics, the government's role is huge in people's life. (FG6-P5)

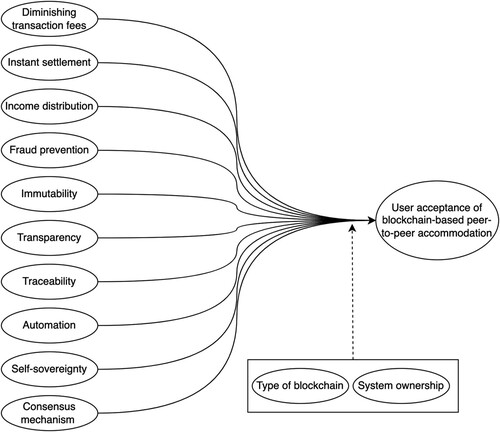

Theoretical contribution: a model of user acceptance of blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation

Based on the study findings, a theoretical model consisting of ten constructs representing predictors of user acceptance of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system was developed (see ). The constructs suggested herein are blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation notions taken from the users’ point of view that are argued to be operationalisable.

Economic benefits are nearly always the primary consideration when individuals engage in commercial activities, including in the sharing economy (Amaro et al., Citation2019; Dabbous & Tarhini, Citation2019; Pappas, Citation2017; Tran & Filimonau, Citation2020; Tussyadiah, Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2020). In that respect, it is expected that improving existing benefits of the sharing system and offering benefits not previously available in existing services (i.e. further reduction of transaction fees, instant settlement, and income distribution) will result in a greater acceptance of blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation services.

Strong technological advantages will result in the continuous use of peer-to-peer accommodation services (Wang et al., Citation2020). Thus, it is expected that the technological advantages of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system, such as fraud prevention, immutability, transparency, traceability, and automation, will also affect user acceptance. The extent to which these benefits are attained will influence the level of acceptance.

Another benefit of utilising blockchain technology is that it empowers users (Niranjanamurthy et al., Citation2019). In this regard, self-sovereignty and consensus mechanisms represent user empowerment aspects of blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation. It is believed that sovereignty over personal information and protection from third-party data collection will appeal to users. In addition, users could also be drawn in by the fact that the entire process will be unbiased, and that they will be treated fairly.

The findings also suggested differences in users’ preferred blockchain type and system ownership model. These should also be considered as additional factors affecting the acceptance of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system.

The proposed model fills the gap in the extant literature and lays the foundation for further research to examine user acceptance of blockchain-based sharing economy in tourism and hospitality management and in other fields. The operationalisation of each construct is translated into low-high-level measurements related to the degree to which the user believes in the indicators of each construct (see ). For example, for the ‘diminishing transaction fees’ construct, using a 5-point Likert scale, 1 (strongly disagree) indicates that the user does not believe that the blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system can significantly reduce transaction fees. On the other hand, 5 (strongly agree) implies that the user strongly believes that the blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system will significantly lower transaction fees.

Table 1. Blockchain-based sharing economy constructs.

Conclusion and implication

Blockchain technology, which was developed to provide secure, smart, and transparent exchanges (Filimonau & Naumova, Citation2020), could further revolutionise the sharing system in tourism and hospitality by ‘democratising’ the existing centralised platform-based business model. Understanding users’ perspectives is thus critical for the sector to reap the benefits of implementing such a system. There is still a significant research gap on the application and acceptance of this new technology, particularly from the users’ perspective (Önder & Gunter, Citation2022). This study filled this critical research gap by investigating the viewpoints of potential users of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system.

This study employed grounded theory with theoretical sampling and three stages of constant comparison technique. It is evidenced that users were enticed to the concept of blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation because it could improve existing benefits of the sharing system while also offering benefits not previously available in existing services. The findings revealed that predictors of user acceptance of such a system are further reduction of transaction fees, instant transaction settlement, wider income distribution, data integrity, algorithm autonomy, and smart protocols. It was also discovered that there were differing preferences regarding the type of blockchain that should be used and who should oversee the system.

The key theoretical contribution of this study is a model of user acceptance of a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system. Developed through theoretical analysis that follows the lens of sharing economy to depict the economic benefits, technological advantages, and user empowerment features of blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation, ten constructs are proposed: diminishing transaction fees, instant settlement, income distribution, fraud prevention, immutability, transparency, traceability, automation, self-sovereignty and consensus mechanism. The proposed model provides a theoretical foundation for further empirical research to assess user acceptance and measure the relative importance of each construct in predicting user acceptance of such a system in various contexts. Thus, this study advances research on emerging technologies in tourism, hospitality, and information systems and management. The model's operationalisation guidelines can also be used for quantitative analysis in future research.

This study also makes important practical contributions. For various stakeholders in hospitality and tourism considering using blockchain technology, the findings in this study provide an overview of what users expect from a blockchain-based peer-to-peer accommodation system. Understanding the benefits users seek from such a system and the relevant personal and social contexts will enable developers and technology providers to utilise desirable characteristics to promote user acceptance. For existing accommodation and sharing platforms, i.e. the incumbent tourism and hospitality businesses, anticipating how blockchain may further revolutionise the industry, the findings might assist in further developing their business strategies to strengthen their unique selling points to remain competitive in the market. Also, the findings demonstrate the dynamics of user acceptance associated with blockchain-type selection and system ownership models. Through this study, stakeholders now have a comprehensive understanding of such an innovation, not just from the standpoint of developers or technology providers but also from the perspective of users.

Despite its contribution, this study has several limitations that need to be addressed in future research. First, it did not involve many participants, which restricts the generalisability of the results. Future studies involving more participants or concentrating on specific user characteristics (i.e. focusing on non-tech-savvy or frequent travellers) may offer additional insights. Second, quantitative research is required to validate this study's theoretical model. Third, in this study, peer-to-peer accommodation services referred to renting accommodations between individuals for independently managed accommodations using technology. This study does not cover peer-to-peer accommodation services with non-commercial exchanges and exchanges not based on technology.

Ethics declarations

We confirm that all the research meets ethical guidelines and adheres to the legal requirements of the study country.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Because this was a grounded theory study that emphasised the representativeness of concepts rather than persons, no personal data was requested. However, many participants voluntarily disclosed some personal information (such as nationality and occupation) during the introductory session and discussion. Gender data was obtained from notes taken by one of the authors who organised the focus groups.

References

- Acquier, A., Daudigeos, T., & Pinkse, J. (2017). Promises and paradoxes of the sharing economy: An organizing framework. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.07.006

- Airbnb. (2021a). Fast Facts. https://news.airbnb.com/about-us/

- Airbnb. (2021b). What are Airbnb service fees? https://www.airbnb.co.uk/help/article/1857/what-are-airbnb-service-fees

- Al-Kuwari, S., Davenport, J. H., & Bradford, R. J. (2011). Cryptographic hash functions: Recent design trends and security notions. IACR Cryptol. EPrint Arch, 2011, 565.

- Amaro, S., Andreu, L., & Huang, S. (2019). Millenials’ intentions to book on airbnb. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(18), 2284–2298. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1448368

- Attaran, M., & Gunasekaran, A. (2019). Blockchain-enabled technology: The emerging technology set to reshape and decentralise many industries. International Journal of Applied Decision Sciences, 12(4), 424–444. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJADS.2019.102642

- Babkin, A., Golovina, T., Polyanin, A., & Vertakova, Y. (2018). Digital model of sharing economy: Blockchain technology management. SHS Web of Conferences, 44, 11. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20184400011

- Belk, R. (2014). You are what you can access: Sharing and collaborative consumption online. Journal of Business Research, 67(8), 1595–1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.10.001

- Benbasat, I., & Barki, H. (2007). Quo vadis TAM? Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 8(4), 7. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00126

- Boeije, H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Quality and Quantity, 36(4), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020909529486

- Buterin, V. (2014). Ethereum: A next-generation smart contract and decentralized application platform [White paper]. Ethereum.org. https://ethereum.org/669c9e2e2027310b6b3cdce6e1c52962/Ethereum_Whitepaper_-_Buterin_2014.pdf

- Buterin, V. (2020). A rollup-centric ethereum roadmap. Ethereum-Magicians.Org. https://ethereum-magicians.org/t/a-rollup-centric-ethereum-roadmap/4698

- Campos-Soria, J. A., Inchausti-Sintes, F., & Eugenio-Martin, J. L. (2015). Understanding tourists’ economizing strategies during the global economic crisis. Tourism Management, 48, 164–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.019

- Casino, F., Dasaklis, T. K., & Patsakis, C. (2019). A systematic literature review of blockchain-based applications: Current status, classification and open issues. Telematics and Informatics, 36, 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.11.006

- Charles, D. X., Lauter, K. E., & Goren, E. Z. (2009). Cryptographic hash functions from expander graphs. Journal of Cryptology, 22(1), 93–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00145-007-9002-x

- Charmaz, K. (1996). The search for meanings – grounded theory. In J. A. Smith, R. Harre, & L. Van Langenhove (Eds.), Rethinking methods in psychology (pp. 27–49). Sage Publications.

- Chatterjee, D., Dandona, B., Mitra, A., & Giri, M. (2019). Airbnb in India: Comparison with hotels, and factors affecting purchase intentions. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 13(4), 430–442. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-05-2019-0085

- Chau, S. C.-K., Xu, J., Bow, W., & Elbassioni, K. (2019). Peer-to-peer energy sharing: Effective cost-sharing mechanisms and social efficiency. Proceedings of the Tenth ACM International Conference on Future Energy Systems, 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1145/3307772.3328312

- Chuttur, M. Y. (2009). Overview of the technology acceptance model: Origins, developments and future directions. Sprouts: Working Papers on Information Systems, 9(37). https://aisel.aisnet.org/sprouts_all/290

- Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00988593

- Dabbous, A., & Tarhini, A. (2019). Assessing the impact of knowledge and perceived economic benefits on sustainable consumption through the sharing economy: A sociotechnical approach. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 149, 119775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119775

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008.

- Davis, F. D., Bagozzi, R. P., & Warshaw, P. R. (1989). User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Management Science, 35(8), 982–1003. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.982

- Etherscan. (2021). Ethereum Gas Tracker. https://etherscan.io/gastracker#historicaldata

- Ferraro, P., King, C., & Shorten, R. (2018). Distributed Ledger Technology, Cyber-Physical Systems, and Social Compliance. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1807.00649.

- Filimonau, V., & Naumova, E. (2020). The blockchain technology and the scope of its application in hospitality operations. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87, 102383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102383

- Gatteschi, V., Lamberti, F., Demartini, C., Pranteda, C., & Santamaría, V. (2018). Blockchain and smart contracts for insurance: Is the technology mature enough? Future Internet, 10(2), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi10020020

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Glaser, B. G. (2014). Applying grounded theory. The Grounded Theory Review, 13(1), 46–50.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1965). Awareness of dying.

- Golosova, J., & Romanovs, A. (2018). The advantages and disadvantages of the blockchain technology. 2018 IEEE 6th Workshop on Advances in Information, Electronic and Electrical Engineering (AIEEE), 1–6.

- Hang, L., & Kim, D.-H. (2019). Sla-based sharing economy service with smart contract for resource integrity in the internet of things. Applied Sciences, 9(17), 3602. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9173602

- Hou, Y., Chen, Y., Jiao, Y., Zhao, J., Ouyang, H., Zhu, P., Wang, D., & Liu, Y. (2017). A resolution of sharing private charging piles based on smart contract. 2017 13Th International Conference on Natural Computation, Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (Icnc-Fskd), 3004–3008.

- Huckle, S., Bhattacharya, R., White, M., & Beloff, N. (2016). Internet of things, blockchain and shared economy applications. Procedia Computer Science, 98, 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2016.09.074

- Islam, M. N., & Kundu, S. (2018). Preserving IoT privacy in sharing economy via smart contract. 2018 IEEE/ACM Third International Conference on Internet-of-Things Design and Implementation (IoTDI), 296–297.

- Jacquemin, H. (2019). Consumers contracting with other consumers in the sharing economy: Fill in the gaps in the legal framework or switch to the blockchain model? IDP: Revista de Internet, Derecho y Politica, 28. https://doi.org/10.7238/idp.v0i28.3179

- Khan, N., & Ouaich, R. (2019). Feasibility analysis of blockchain for donation-based crowdfunding of ethical projects. In Ahmed Al-Masri & Kevin Curran (Eds.), Smart technologies and innovation for a sustainable future (pp. 129–139). Springer.https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01659-3_17.

- Kundu, D. (2019). Blockchain and trust in a smart city. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 10(1), 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425319832392

- Langley, P., & Leyshon, A. (2017). Platform capitalism: The intermediation and capitalization of digital economic circulation. Finance and Society, 3(1), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.2218/finsoc.v3i1.1936

- Lecuyer, M., Tucker, M., & Chaintreau, A. (2017). Improving the transparency of the sharing economy. Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on World Wide Web Companion, 1043–1051.

- Li, B., Wang, Y., Shi, P., Chen, H., & Cheng, L. (2018). FPPB: A fast and privacy-preserving method based on the permissioned blockchain for fair transactions in sharing economy. 2018 17th IEEE International Conference On Trust, Security And Privacy In Computing And Communications/12th IEEE International Conference On Big Data Science And Engineering (TrustCom/BigDataSE), 1368–1373.

- Lian, J.-W., Chen, C.-T., Shen, L.-F., & Chen, H.-M. (2020). Understanding user acceptance of blockchain-based smart locker. The Electronic Library, 38(2), 353–366. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-06-2019-0150

- Liu, Z., Li, Y., Liu, Y., & Yuan, D. (2018). Sharing economy protocol with privacy preservation and fairness based on blockchain. In Xingming Sun, Zhaoqing Pan, & Elisa Bertino (Eds.), Cloud Computing and Security. ICCCS 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol. 11068, pp. 59–69). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00021-9_6

- Locher, T., Obermeier, S., & Pignolet, Y. A. (2018). When can a distributed ledger replace a trusted third party? 2018 IEEE International Conference on Internet of Things (IThings) and IEEE Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom) and IEEE Cyber, Physical and Social Computing (CPSCom) and IEEE Smart Data (SmartData), 1069–1077.

- Lunceford, B. (2009). Reconsidering technology adoption and resistance: Observations of a semi-luddite. Explorations in Media Ecology, 8(1), 29–48.

- Mao, Z. E., Jones, M. F., Li, M., Wei, W., & Lyu, J. (2020). Sleeping in a stranger’s home: A trust formation model for airbnb. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 42, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.11.012

- Murillo, D., Buckland, H., & Val, E. (2017). When the sharing economy becomes neoliberalism on steroids: Unravelling the controversies. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 125, 66–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.05.024

- Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. http://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf

- Narasimhan, C., Papatla, P., Jiang, B., Kopalle, P. K., Messinger, P. R., Moorthy, S., Proserpio, D., Subramanian, U., Wu, C., & Zhu, T. (2018). Sharing economy: Review of current research and future directions. Customer Needs and Solutions, 5(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40547-017-0079-6

- Narasimhan, C., Papatla, P., & Ravula, P. (2016). Preference segmentation induced by tariff schedules and availability in ride-sharing markets. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Milwaukee, WI, USA, Working Study.

- Niranjanamurthy, M., Nithya, B. N., & Jagannatha, S. (2019). Analysis of blockchain technology: Pros, cons and SWOT. Cluster Computing, 22(6), 14743–14757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10586-018-2387-5

- Önder, I., & Gunter, U. (2022). Blockchain: Is it the future for the tourism and hospitality industry? Tourism Economics, 28(2), 291–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354816620961707

- Pandey, N., & Pal, A. (2020). Impact of digital surge during COVID-19 pandemic: A viewpoint on research and practice. International Journal of Information Management, 55, 102171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102171

- Pappas, N. (2017). The complexity of purchasing intentions in peer-to-peer accommodation. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(9), 2302–2321. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2016-0429

- Puschmann, T., & Alt, R. (2016). Sharing economy. Business & Information Systems Engineering, 58(1), 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12599-015-0420-2

- PwC. (2015). The sharing economy – Consumer Intelligence Series.

- PwC. (2020). Eight emerging technologies and six convergence themes you need to know about. https://www.pwc.com/us/en/tech-effect/emerging-tech/essential-eight-technologies.html

- Rahman, M. A., Rashid, M. M., Hossain, M. S., Hassanain, E., Alhamid, M. F., & Guizani, M. (2019). Blockchain and IoT-based cognitive edge framework for sharing economy services in a smart city. IEEE Access, 7, 18611–18621. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2896065

- Reid, D. J., & Reid, F. J. M. (2005). Online focus groups: An in-depth comparison of computer-mediated and conventional focus group discussions. International Journal of Market Research, 47(2), 131–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/147078530504700204

- Reybold, L. E., Lammert, J. D., & Stribling, S. M. (2013). Participant selection as a conscious research method: Thinking forward and the deliberation of ‘emergent’findings. Qualitative Research, 13(6), 699–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112465634

- Schor, J. (2016). Debating the sharing economy. Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics, 4(3), 7–22. https://doi.org/10.22381/JSME4320161

- Schor, J. B., & Fitzmaurice, C. J. (2015). Collaborating and connecting: The emergence of the sharing economy. In Handbook of research on sustainable consumption (pp. 410–425). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Szabo, N. (1994). Smart Contracts, Retrived from: http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/rob/Courses/InformationInSpeech/CDROM/Literature. LOTwinterschool2006/Szabo. Best. Vwh. Net/Smart. Contracts. Html

- Tran, T. H., & Filimonau, V. (2020). The (de) motivation factors in choosing airbnb amongst Vietnamese consumers. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 42, 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.10.011

- Tuomi, A., Tussyadiah, I. P., & Hanna, P. (2021). Spicing up hospitality service encounters: The case of pepper™. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(11), 3906–3925. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2020-0739

- Tussyadiah, I. P. (2015). An exploratory study on drivers and deterrents of collaborative consumption in travel. In Iis Tussyadiah & Alessandro Inversini (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2015 (pp. 817–830). Springer.

- Tussyadiah, I. P. (2016). Factors of satisfaction and intention to use peer-to-peer accommodation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 55, 70–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.03.005

- Tussyadiah, I. P., & Pesonen, J. (2016). Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. Journal of Travel Research, 55(8). https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515608505.

- Tussyadiah, I. P., & Pesonen, J. (2018). Drivers and barriers of peer-to-peer accommodation stay–an exploratory study with American and Finnish travellers. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(6), 703–720. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2016.1141180

- Underwood, S. (2016). Blockchain beyond bitcoin. Communications of the ACM, 59(11), 15–17. https://doi.org/10.1145/2994581

- Venkatesh, V. (2000). Determinants of perceived ease of use: Integrating control, intrinsic motivation, and emotion into the technology acceptance model. Information Systems Research, 11(4), 342–365. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.11.4.342.11872

- Venkatesh, V., & Davis, F. D. (2000). A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Management Science, 46(2), 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.46.2.186.11926

- Venkatesh, V., Morris, M. G., Davis, G. B., & Davis, F. D. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 425–478. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036540.

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y., & Xu, X. (2012). Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quarterly, 36(1), 157–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/41410412.

- Wang, Y., Asaad, Y., & Filieri, R. (2020). What makes hosts trust airbnb? Antecedents of hosts’ trust toward airbnb and its impact on continuance intention. Journal of Travel Research, 59(4), 686–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519855135

- Wiesche, M., Jurisch, M. C., Yetton, P. W., & Krcmar, H. (2017). Grounded theory methodology in information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 41(3), 685–701. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.3.02

- Wilkinson, S. (1998). Focus group methodology: A review. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 1(3), 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.1998.10846874

- Wu, J., Zeng, M., & Xie, K. L. (2017). Chinese travelers’ behavioral intentions toward room-sharing platforms: The influence of motivations, perceived trust, and past experience. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(10), 2688–2707. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2016-0481

- Xiao, S. (2020). Research on the information security of sharing economy customers based on block chain technology. Information Systems and E-Business Management, 18(4), 487–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-018-0380-4

- Xu, L., Shah, N., Chen, L., Diallo, N., Gao, Z., Lu, Y., & Shi, W. (2017). Enabling the sharing economy: Privacy respecting contract based on public blockchain. Proceedings of the ACM Workshop on Blockchain, Cryptocurrencies and Contracts, 15–21.

- Ye, S., Ying, T., Zhou, L., & Wang, T. (2019). Enhancing customer trust in peer-to-peer accommodation: A “soft” strategy via social presence. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 79, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.11.017