ABSTRACT

This study investigates the complex relationship between residents and national parks in a top nature-based destination, Poland's Tatra and Podhale region. Utilizing a door-to-door survey of 511 respondents from 26 towns around Tatra National Park (TNP), the research employs two-step structural equation modeling and fsQCA to analyze how place attachment and preferences for nature protection strategies interact. Contrary to the widely held view that tourism development positively influences attitudes toward national parks, we found tourism growth in the communities surrounding TNP impacts how these communities relate to the protected area. The study concludes that for TNP to gain broader community support, it is crucial to convey to residents their essential role as a tourism asset. This finding has wider implications for how national parks and adjacent communities can coexist harmoniously in areas experiencing rapid tourism expansion.

Introduction

While protected areas are globally recognized as critical for biodiversity conservation, their effectiveness is often amplified when supported by adjacent communities (Andrade & Rhodes, Citation2012; Bennetta & Deardenc, Citation2014; Gruber, Citation2010; Oldekop et al., Citation2016; Waylen et al., Citation2010). The tourism sector is commonly viewed as a catalyst for bolstering such local support, largely due to the economic advancement it brings (Boyle & Green, Citation2016; Eagles et al., Citation2002; Goodwin, Citation2002; Heslinga et al., Citation2017; Idrissou et al., Citation2013; Mehta & Heinen, Citation2001; Spenceley & Snyman, Citation2017). This notion is underpinned by the opportunity that protected areas present for tourism businesses. Consequently, communities in close proximity to these conservation zones, like national parks, are thought to benefit economically, reinforcing their support for conservation initiatives.

Nonetheless, as tourism introduces various social and economic shifts in local communities, such as job creation, expansion of businesses, economic reliance, or diversification, these transformations could potentially modify the way residents engage with nearby protected areas over the long term (i.e. Budowski, Citation1976; Lee, Citation2008; Strzelecka, Boley, et al., Citation2017; Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al., Citation2017; Williams et al., Citation1992). Right now, we don't fully know how growing tourism affects what locals think about nearby protected areas like national parks, particularly in consolidated nature-based destinations. These popular places often feature mountain regions like the Alps and the Tatras, which offer a diverse array of outdoor activities including ski resorts.

One way to shed light on the above phenomenon is to use the place attachment lens. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the bonds residents have with their locale significantly affect their perceptions of adjacent national parks (Baral & Heinen, Citation2007; Marshall et al., Citation2010; Nyaupane & Poudel, Citation2011; Sah & Heinen, Citation2001; Stedman, Citation2002; Strzelecka et al., Citation2021). However, as tourist destinations expand and evolve, the character of place bonds between residents and their local environment may also undergo changes (Boley et al., Citation2021). This particular aspect has been largely neglected in scholarly literature that discussed place attachment and the development of tourism in getaway communities. This leaves a gap in our understanding of how resident-place bonds shape attitudes towards national parks in communities that have transformed into hubs for large-scale, nature-based tourism.

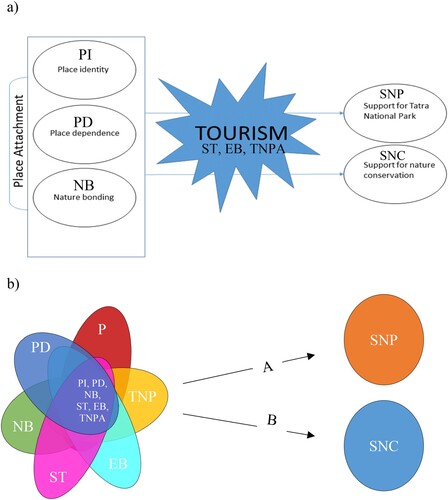

In response to the aforementioned gap, this study investigates how people living in Poland's top nature-focused tourist area, Tatra and Podhale, perceive the nearby Tatra National Park and conservation efforts in general. Specifically, we seek to understand how resident-place bonds influence these perceptions, and what is the effect of tourism growth ((a)). Subsequently, we scrutinize the behavioral mechanisms that underpin individual dispositions towards nature conservation efforts (i.e. attitudes toward a national park versus nature conservation) ((b)).

Figure 1. The relationship between people-park-tourism. (1a) symmetric model*; (1b) asymmetric model*.

Note: A: SNP = f(PI, PD, NB, ST, EB, TNPA); B: SNC = f(PI, PD, NB, ST, EB, TNPA) *PI - Place Identity; PD - Place Dependence; NB - Nature Bonding; ST - Support for Tourism; EB - Economic Benefits; TNPA - Tatra Mountains National Park as Tourist Attraction; SNP - Support for National Park; SNC - Support for Nature Conservation.

To that end, we integrate theories of social exchange (Emerson, Citation1976) and place attachment (Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010; Tuan, Citation1974) in our analytical framework. Social exchange provides a robust conceptual lens to explain the role that perceived benefits of the protected area play for community conservation attitudes in tourism destinations (Brinberg & Castell, Citation1982) as well as helps understand the effects of tourism on the local conservation attitudes (Choi & Murray, Citation2010; Jurowski & Gursoy, Citation2004; Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2010; Scannell & Gifford, Citation2010). Essentially, the social exchange framework would suggest that when the perceived benefits of having Tatra National Park for nature conservation outweigh the perceived costs associated with having the Park, residents would be more inclined to support the conservation policy behind it. As for place attachment theory, it provides this study with insights into the relationship between place bonds and perceptions of nature conservation through the national park. The place attachment theory proposes that place bonds develop as a result of place change, emphasizing that development can undermine the quality of people's bonds with local places of nature protection (Cross, Citation2015; Goudriaan et al., Citation2023).

This research offers a dual contribution to the field of tourism. Firstly, it underscores the complex ways in which varying forms of place attachment in well-established, nature-focused destinations may complicate conservation efforts. Secondly, from a methodological standpoint, our study synergizes structural equation modeling (SEM) with fsQCA, thereby enriching our understanding of the Tatra and Podhale region. The SEM approach helps to identify the connections between residents’ attachment to place and their preferences for conservation strategies in high-traffic mountainous areas like Tatra and Podhale. In contrast, the asymmetric approach yields nuanced insights into the variances in residents’ support for general nature conservation versus support fot Tatra National Park. Collectively, the insights garnered from this study have significant ramifications for the sustainable management of mature nature-based tourist destinations.

Study area

Tatra National Park (TNP) is the most visited national park in Poland (Skawinski, 2010) (4.8 million visitors in 2021), with Zakopane (40,000 beds) and the surrounding villages (approx. 110,000 beds) being central getaways for mountain tourism and winter sports and in the Carpathians (Mika, Citation2023). The park's surrounding area represents the traditional highlander folklore of the Podhale region (Dziadowiec, Citation2010; Kroh, Citation2002; Radwańska-Paryska & Paryski, Citation2004). Highlanders have a strong bond with the land that is deeply embedded in their culture and has been passed down from generation to generation (Kucina, Citation2007). This cultural heritage distinguishes this region from the northern parts of the Carpathians (Dziadowiec, Citation2010).

TNP was established in 1955 on land the state had appropriated from local landowners (Hibszer, Citation2008). Land expropriation generated a feeling of injustice among highlanders, starting an ongoing conflict between the landowners and the park (Komorowska, Citation2000). Fast-increasing land and timber markets in Poland during the 1990s motivated local communities to demand that the state returns the appropriated land to families that used to own the land (Kucina, Citation2007). Landowners sought to undermine the legitimacy of land appropriation acts, arguing that it was detrimental to their wellbeing because the compensations offered by the state did not reflect the actual value of the land (Kucina, Citation2007; Radwańska-Paryska & Paryski, Citation2004). Moreover, residents felt entitled to economic benefits from visitors to the park.

Local groups have expressed interest in revising land acquisition acts to profit from the TPN resources (timber, park entrance fees, and shares in real estate used for ski tourism) (Kucina, Citation2007). The most popular way to lay claim is by membership in a local association or a group lobbying TNP and state authorities (Komorowska, Citation2000; Kucina, Citation2007). Competing interests among local interest groups tend to undermine a mutually satisfying agreement between local communities and the TNP management. Local disputes (e.g. highlanders-shepherds, highlanders-businessmen) and divided claims against the TNP were noticeable already in the 1990s (Kucina, Citation2007).

Conceptual foundations and hypothesis development

Social exchange theory (SET) refers to a two-sided rewarding process involving two or more social groups (Emerson, Citation1976). It proposes that interactions may provide opportunities for rewarding and satisfying exchanges (Sutton, Citation1967). People's evaluations of perceived rewards and the costs of their relationships influence the stability of those relationships.

Social exchange can provide insights into resident attitudes towards conservation strategy through the national park in a trending tourism region. It accommodates an explanation of both positive and negative perceptions of the park and provides the rationale to examine exchanges at the individual or collective level (Ap, Citation1992, p. 667). For example, protected areas may be perceived to be economically beneficial to residents in adjacent communities, including employment or income from protected area tourism (Allendorf, Citation2022; Buckley et al., Citation2019). Other benefits may include directly using a protected area for recreation or ecosystem services (Jackson & Naughton-Treves, Citation2012). Generally, in accordance with SET, if residents view a protected site as valuable to their livelihoods, they will support it.

Moreover, SET has also been frequently employed to explain attitudinal outcomes of tourism exchanges (Boley et al., Citation2014; Gursoy & Rutherford, Citation2004; Perdue et al., Citation1990; Stylidis et al., Citation2014). Correspondingly, it has been asserted that perceived tourism benefits and costs influence residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Namely, the interaction between residents and visitors is usually sustained if both sides can envision positive outcomes.

In addition to the cognitive process, the classic works on social exchange contain references to various emotions (Blau, Citation1964; Homans, Citation1961; Thibaut & Kelley, Citation1959). Each actor participating can have emotions that affect decisions concerning the pattern and nature of exchange (Lawler & Shane, Citation1999). With emotions being a substantial factor affecting attitudes, SET further empowers place attachment theory to better explain the potential impacts of residents’ place bonds on their perceptions of protected areas (Cundill et al., Citation2017).

Place attachment defines personal sentiment towards a place or community (Goudy, Citation1990; Tuan, Citation1974) developed through meanings ascribed to them (Low & Altman, Citation1992; Stedman, Citation2003). In tourism research, place attachment is often conceptualized as comprising emotional (place identity) and functional (place dependence) attachments. However, Raymond et al. (Citation2010) added a nature bonding component to reflect how people relate to local nature (Raymond et al., Citation2010; Strzelecka, Boley, et al., Citation2017; Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al., Citation2017).

Place identity arises from values, attitudes, and beliefs about and direct experiences of the physical world (Proshansky et al., Citation1983). It is shaped by thinking of and reflecting on places (Tuan, 1980 in Proshansky et al., Citation1983, p. 61). On the other hand, place dependence refers to the attachment to a place because of its instrumental value in achieving the desired goal. In other words, place dependence reflects situations when a place becomes a resource for satisfying goals (Williams et al., Citation1992). Place dependence is ‘embodied in the area's physical characteristics and may increase when the place is close enough to allow for frequent visitation’ (Williams & Vaske, Citation2003, p. 831). Nature bonding simply refers to ‘an implicit or explicit connection to some part of the non-human natural environment, based on history, emotional response or cognitive representation (e.g. knowledge generation)’ (Raymond et al., Citation2010, p. 426). Nature bonds emerge from an individual experience, time spent in the natural environment, or individual capacity to affect the natural surroundings (Gustafson, Citation2001).

Place attachment and resident attitudes

Scholars have extensively studied place attachment in relation to residents’ attitudes toward tourism development (e.g. Chen et al., Citation2021; Choi & Murray, Citation2010; Draper et al., Citation2011; Gursoy & Rutherford, Citation2004; McGehee & Andereck, Citation2004; Strzelecka, Boley, et al., Citation2017; Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al., Citation2017). For example, in a study of rural communities in Poland, Strzelecka, Boley, et al. (Citation2017), Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al. (Citation2017) found that residents’ bonds with local nature influence perceptions of tourism benefits. The results are, however, generally mixed. Draper et al. (Citation2011) reported that more attached residents tend to be less favorable toward tourism development. Draper et al.’ (Citation2011) results are similar to those of Ramkissoon and Nunkoo (Citation2011), who stated that people's emotional bond with local places can be challenged by changes they experience while living in tourist destinations. The more attached residents will likely be less optimistic about tourism development in those circumstances.

Consequently, the positive association between place attachment and attitudes toward tourism is likely to be the result of tourism supporting how residents identify with their communities and their expectations of the role these communities will play in their lives. In contrast, the negative relationship between place attachment and resident support for tourism will signal that tourism disturbs bonds between residents and local places (Lalicic & Garaus, Citation2022). Thus, we propose to test the following hypotheses.

H1a: Place Identity predicts Support for Tourism.

H1b: Place Dependence predicts Support for Tourism.

H1c: Nature Bonding predicts Support for Tourism.

It remains, however, that relatively little research has been conducted that takes into account the context of tourism development in order to examine the relationship between place attachment and resident attitudes towards protected areas. Several studies have explored the association between place bonds and pro-environmental attitudes (e.g. Devine-Wright, Citation2009; Devine-Wright & Howes, Citation2010; Gosling & Williams, Citation2010; Raymond et al., Citation2010). For example, Wynveen et al. (Citation2021) found that place attachment mediates the relationship between environmental worldview and support for wilderness among residents of the southeastern United States. Other studies have shown that nature bonds are particularly important in influencing pro-environmental attitudes (Cheng & Monroe, Citation2012; Halpenny, Citation2010; Vaske & Kobrin, Citation2001). Additionally, Uysal et al. (Citation1994) found that ecocentric views are accompanied by a preference for preserving local nature through the establishment of protected areas such as national parks.

Prior research suggests that the quality of place bonds may directly affect residents’ attitudes toward conservation efforts. The relationship between different components of place attachment and resident preferences regarding conservation strategies has yet to be established. Therefore, we propose to test the following hypotheses:

H2a: Place Identity predicts Support for Nature Conservation.

H2b: Place Dependence predicts Support for Nature Conservation.

H2c: Nature Bonding predicts Support for Nature Conservation.

H2d: Place Identity predicts Support for TNP.

H2e: Place Dependence predicts Support for TNP.

H2f: Nature Bonding predicts Support for TNP.

Tourism and resident attitudes

Tourism and recreation opportunities around protected areas can benefit residents and visitors alike (Boyle & Green, Citation2016; Lockwood et al., Citation2005). For example, research shows residents are happier about creating and maintaining protected areas like national parks when they feel they benefit from them, such as through tourism activities in the park (Marcus, Citation2001). Likewise, viewing a national park as supporting local livelihoods can improve residents’ perceptions of the park (Sekhar, Citation2003; Sirivongs & Tsuchiya, Citation2012) and whether they support it.

While past evidence that economic benefits from tourism may improve general attitudes toward a protected area (e.g. Kinnaird & O’Brien, Citation1996; Kiss, Citation2004; Kruger, Citation2005; Lindberg et al., Citation1996; Ross & Wall, Citation1999; Stone & Wall, Citation2004), residents perceptions in how they perceive the protected area may vary depending on whether they benefit from tourism or more broadly on whether they support tourism in the region. Finally, tourism development may change peoples’ fundamental beliefs about nature protection and how it should be implemented (Stem et al., Citation2003). To address these concerns, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3a: Economic Benefits from Tourism predict Support for Nature Conservation.

H3b: Economic Benefits from Tourism predict Support for TNP.

H3c: Economic benefits from Tourism predict the perception of TNP as a Tourist Attraction.

The effect of economic benefits from tourism on resident support for tourism has been a central issue discussed within the literature (e.g. Madrigal, 1993; Perdue et al., Citation1990; Sharpley, Citation2014; Strzelecka, Boley, et al., Citation2017; Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al., Citation2017). Madrigal (1993) noted that the positive relationship between perceptions of tourism and economic reliance on the tourism sector had been the most consistent finding over the years. With such an abundance of evidence, we simply seek to confirm the following hypothesis:

H3d: Economic benefits from tourism predicts Support for Tourism.

While it has been well established that economic benefits affect tourism attitudes, the relationship between resident perceptions of a protected area as tourist attraction and resident support for it has not yet been studied. As of now we only understand that when residents believe the local protected area is a driving force for tourism development in the region, they are more likely to support it because they view it as a resource to improve community livelihood (Abukari & Mwalyosi, Citation2020).

To further explore the issue this study puts forth the following hypotheses:

H4a: Perception of TNP as a Tourist Attraction predicts Support for Nature Conservation.

H4b: Perception of TNP as a Tourist Attraction predicts Support for TNP.

H4c: Perception of TNP as a Tourist Attraction predicts Support for Tourism.

In reference to the relationship between resident tourism attitudes and support for nature conservation, Walpole and Goodwin (Citation2002) found that in case of Komodo National Park (Indonesia) resident positive attitudes towards tourism were associated with support for conservation. Given the scarcity of research, we further test the relationship between tourism attitudes and nature conservation attitudes by testing the following hypotheses:

H5a: Support for Tourism predicts Support for Nature Conservation.

H5b: Support for Tourism predicts Support for TNP.

Finally, we propose that residents who support nature conservation may be more likely to view the national park as a conservation strategy positively. Thus, we formulated the following hypothesis to be tested.

H6a: Support for Nature Conservation predicts Support for TNP.

Methods and Materials

Measurements

The measurement of place attachment was derived and adapted from Williams and Vaske (Citation2003) (Place Identity and Place Dependence) and Raymond et al. (Citation2010) (Nature Bonding) to ensure functional and conceptual equivalence. This instrument was previously proven valid and reliable in the Polish context (Strzelecka, Boley, et al., Citation2017; Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al., Citation2017). Economic benefits from tourism were assessed with Boley et al.’s (Citation2018) Economic Benefits from Tourism Scale, which was also previously deemed a valid and reliable measure of economic benefits from tourism in Poland. Similarly, Boley et al.’s (Citation2018) Support for Tourism was used to measure resident attitudes towards tourism and was previously used in Poland (Strzelecka, Boley, et al., Citation2017; Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al., Citation2017). Support for Tatra National Park and Support for Nature Conservation (in Tatra) were adapted with modifications from the Boley et al.’s (Citation2018) measure of attitudes toward tourism. Finally, we assessed residents’ perceptions of Tatra National Park as a visitor attraction. All constructs were measured with a 1–4 range Likert scale (1 strongly disagree to 4 strongly agree), removing the option ‘unsure/undecided’. The strategy was adopted to overcome issues linked to the people’s tendency to select the ‘middle’ and ‘undecided’ options.

Data collection area and sample

The distribution of the survey instrument corresponded with the actual number of residents in each municipality, with the goal of using a census-guided systematic random sampling scheme following the previous work of Strzelecka, Boley, et al. (Citation2017); Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al. (Citation2017). The sampling procedure was designed to provide a heterogeneous sample representative of the administrative area of Tatra County. Criteria for selecting respondents included residency, gender, and age.

Responses were collected in each of the 26 towns in the region. Starting in randomly selected locations in each town, every household in those selected locations was visited by the research team of trained volunteers until the quota was met. Then, one person from each home was asked to participate in the study. If the resident agreed, a survey instrument was left with the participant and picked up later that day or the following day by the research team (i.e. two returns), following the methodology from Strzelecka, Boley, et al. (Citation2017); Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al. (Citation2017). Data were collected during the winter of 2019/2020, before the COVID-19 pandemic. Altogether, n = 511 questionnaires were deemed usable. 54% were females, and 46% were males. Most respondents lived in the Tatra and Podhale region for a few generations (83.7%), while only 16.3% of respondents did not live there since birth. Regarding age, 9% of respondents were between 18 and 24 years old, 19.4% between 25 and 34, 19% between 35 and 44 years old, 17.1% of respondents between 55 and 64, and 17.3% were older than 65. Employment and income information are presented in .

Table 1. Employment & income. The table presents demographic information of the study participants.

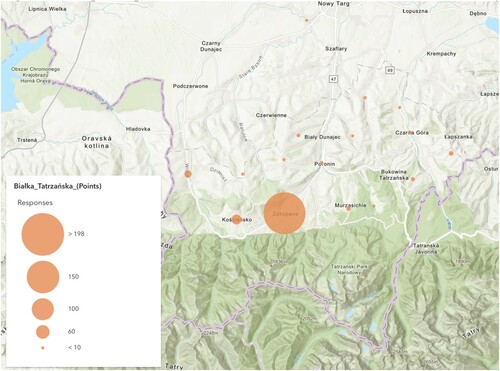

The proposed symmetrical model and associated hypotheses were tested using two-step structural equation modeling (Anderson & Gerbing, Citation1988) based on survey data collected from residents in municipalities surrounding Tatra National Park (TNP) (). TNP is located within the boundaries of four rural municipalities (Biały Dunajec, Bukowina Tatrzańska, Kościelisko, Poronin), and the city of Zakopane and the population of 68 thousand people living next to TNP (Statistics Poland, Local Data Bank: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/bdl/dane/podgrup/tablica, 19 July 2022).

Measurement model assessment: confirmatory factor analysis (CFA)

A measurement model was assessed using CFA and included Place Attachment, Economic Benefit from Tourism (EBTS), Support for Tourism (ST); the Perception of TNP as a Tourist Attraction (TNPA); Support for TNP (STNP), and Support for Nature Conservation (SNC). CFA for the constructs was run in IBM SPSS AMOS 26 Graphics. Results from the three CFAs revealed a good model fit of a parsimonious solution and construct valid measures (; in Appendix).

Results

Results structural equation modeling (SEM)

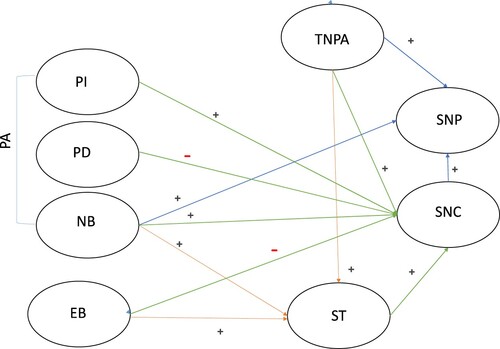

SEM was performed to determine support for the proposed hypotheses. Model fit was slightly reduced in all three structural models compared to the CFAs (CFI = 0.938, RMSEA = 0.058). However, model fit estimates are consistently lower for structural models when compared to measurement models because SEM models are recursive (Hair et al., Citation2021). presents significant relationships in the parsimonious SEM solution, whereas shows results for the regression paths (both significant and not significant).

Figure 3. Parsimonious model (only p-value of 0.05 or lower).

Table 2. Result of hypotheses testing. The table presents results of hypothesis testing.

Regarding Support for Tourism among the respondents, a significant relationship was found between Nature Bonding and Support for Tourism (β = 0.20, p < 0.001; H1c), Perception of TNP as a Tourist Attraction, and Support for Tourism (β = 0.09, p = 0.048; H4c). A predicted significant relationship between Economic Benefits and Support for Tourism was also confirmed (β = 0.43, p = 0.02; H3d). However, the relationships between (1) Place Identity and Support for Tourism (β = 0.12, p = 0.055; H1a), as well as Place Dependence and Support for Tourism were insignificant (β = 0.01, p = 0.905; H1b)

Regarding support for the TNP, a significant relationship was found between Nature Bonding and Support for the TNP (β = 0.14, p = 0.045; H2f) and between the Perception of TNP as a Tourist Attraction and Support for the TNP (β = 0.30, p = 0.001; H4b). A significant positive relationship was also found between Support for Nature Conservation and Support for TNP (β = 0.36, p = 0.001; H6a). However, no significant relationship was found between Place Identity and Support for the TNP (β = −0.131, p = 0.050; H2d) or Place Dependence and Support for the TNP (β = 0.043, p = 0.355; H2e). Additionally, there was no significant relationship between resident Support for the TNP and their Support for Tourism (β = −0.05, p = 0.395; H5b)

Regarding Support for Nature Conservation, significant positive relationships were found between Nature Bonding and Support for Nature Conservation (β = 0.25, p = 0.001; H2c), Place Identity and Support for Nature Conservation (β = 0.12, p = 0.049; H2a). In addition, those who scored high on Support Tourism were also more likely to express higher Support for Nature Conservation (β = 0.12, p = 0.022; H5a). Similarly, those who perceived TNP as a Tourist Attraction were more likely to support Nature Conservation (β = 0.28, p = 0.001; H4a).

However, significant negative relationships were found between Place Dependence and Support for Nature Conservation (β = −0.23, p = 0.001; H2b) and between Economic Benefits and Support for Nature Conservation (β = −0.15, p = 0.004; H3a). Importantly, Economic Benefits from tourism are not a significant predictor of resident Support for TNP (β = -−003, p = 0.958; H3b). Similarly, Economic Benefits are not linked to residents Perception of TNP as a Tourist Attraction (β = −0.15, p = 0.004; H3c)

Results of fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA)

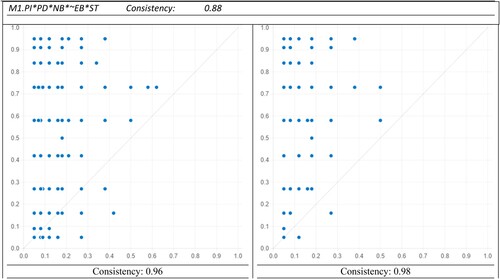

To determine the asymmetric relationships between the predicting variables and the outcome, we further applied fsQCA to understand how different constellations of predicting variables formulate recipes that result in the desired outcome (). Two configural models are fed into the fsQCA algorithms naming SNP = f (PI, PD, NB, ST, EB, TNPA) and SNC = f(PI, PD, NB, ST, EB, TNPA). We followed the guidelines of Ragin (Citation2009) to perform the fsQCA analysis. First, the data was calibrated through log-odds metric to fuzzy set membership scores of [0, 1] range with 0.95 as a full member, 0.05 as a full non-member, and 0.5 as the intermediate. Second, the constructed truth table portrays all possible configurations that may occur. Here, the cases not explained in the sample are omitted from the further calculation. Finally, once removing configurations with low frequencies (<1), fsQCA uses Boolean algebra and Quine McCluskey algorithms to calculate the number of possible configurations with a minimum recommended consistency of 0.75 (Rihoux & Ragin, Citation2009).

As presented in , fsQCA reveals two models for combining all conditions needed to support national parks (arrow A in (a)). As such, M1 (PI*PD*NB*∼EB*ST) provides details for supporters of the natural park who scored higher on place identity, place dependence, nature bonding, and support for tourism but not on economic benefit. On the other hand, the different recipe (M2: PI*∼PD*NB*ST*TNPA) reveals that cases scored higher on place identity, nature bond, support for tourism, and TNP as a tourist attraction, but perceived lower place dependence are also the supporters of a national park. Furthermore, fsQCA analysis on support for nature conservation in Tatra (arrow B in (b)) illuminates two recipes for the occurrence of the outcome (SNC). Consequently, M3 (PI*PD*NB*ST) in reveals cases that scored high on place identity, place dependence, nature bond, and support for tourism to be better supporters of nature conservation in the Tatra area. Another recipe (M4: PI*NB*ST*TNPA) explains those with higher place identity, nature bonding, support for tourism, and perception of TNP as a tourist attraction have scored higher in their support for nature conservation in the area.

Table 3. Results of fsQCA: conditions for SNP and SNC. Table presents pathways that lead to supporter of nature conservation in the Tatra region.

FsQCA also provides insights into the negation of the outcome. It suggests that the recipes explaining the presence of an outcome are not necessarily mirrored opposites of those explaining the absence of the outcome. illustrates the recipes for the negation of SNP (i.e. ∼SNP) and negation of SNC (i.e. ∼SNC). Consequently, even though the two models predict ∼SNP (M5 and M6), there is no satisfying solution with enough coverage and consistency for ∼SNC because there are simply not many cases that score lower on ∼SNC.

Table 4. Results of fsQCA for antecedents predicting negation of SNP and negation of SNC. Table presents pathways that lead to lack of support of nature conservation in the Tatra region.

Necessary condition analysis results

Using SEM and Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) enables researchers to identify the must-have factors required for an outcome under the necessity logic (Richter et al., Citation2020). Unlike sufficient configurations, single necessary antecedents are critically important within the recipes for the occurrence of the desirable outcome (Ragin, Citation2009). demonstrates the results of NCA, where a cut-off consistency level of .90 is recommended as a selection criterion (Olya, Citation2020). Consequently, PI, NB, and ST were identified as the single necessary conditions without which support for the national park will not occur. This result highlights the importance of strategies that encourage these necessary conditions.

Table 5. Result of necessary condition analysis. Table presents result of Necessary Condition Analysis in asymmetric modeling.

Result of predictive validity

We divided the sample into two subsamples to predict the out-of-sample forecasting power of the fsQCA models. Then, using M1 from the results of fsQCA () from the original sample, we portrayed a fuzzy XY plot to compare the consistency of the model in two subsamples. provides evidence of predictive validity.

Discussion

A better understanding of how residents in consolidated natudestinations perceive local protected areas is necessary to ensure the success of biodiversity conservation efforts. Using social exchange and place attachment theories, this study examined how residents’ support for nature preservation and the protected area of Tatra National Park in the Podhale region of Poland are influenced by their sense of place attachment and their views of tourism. In the following paragraphs, we discuss our findings in relation to a broader body of literature.

Importantly, only the relationship between nature bonding dimension of place attachment and positive attitude toward tourism was significant (H1c). Neither the place identity nor place dependence dimensions of place attachment were shown to influence residents’ attitudes towards tourism (H1a; H1b). These mixed findings are in line with results from the past studies (see: Choi & Murray, Citation2010; Draper et al., Citation2011; Gursoy & Rutherford, Citation2004; McGehee & Andereck, Citation2004; Strzelecka, Boley, et al., Citation2017; Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al., Citation2017), and especially with research by Strzelecka, Boley, et al. (Citation2017); Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al. (Citation2017)., who found relation between residents’ nature connection and their perceptions of tourism benefits.

Our findings also present direct evidence that strength of residents’ place attachment predicts residents’ attitudes to nature conservation in the consolidated nature-based destination of Tatra and Podhale region. Precisely, we learned that the greater place identity or bond with local nature the greater resident support for nature conservation. Thus, the residents who identify with their communities and local nature may wish to preserve the places and nature they have developed bonds with. Those findings appear to be consistent with prior studies focused on the effect of place bonds on environmental attitudes (Cheng & Monroe, Citation2012; Halpenny, Citation2010; Vaske & Kobrin, Citation2001) and studies exploring the effect of place attachment on pro-environmental behaviors (Devine-Wright & Howes, Citation2010; Gosling & Williams, Citation2010; Hernández et al., Citation2010).

Notably, however, the significant negative relationship between residents’ place dependency and their attitudes toward nature conservation highlights that greater resident dependence on the local facilities, amenities, or other types of infrastructure (including tourism facilities) may decrease support for conservation of local natural resources. Perhaps, expansion of tourism changes what residents care about in their community. Consolidating nature-based destinations undergo changes in what they offer residents, which in turn affects what those residents value about living in such destinations (Kaján, Citation2014). As the region urbanizes, tourism infrastructure and attractions developed for visitors diminish the importance of nature for residents in the region, as daily life becomes increasingly entangled with the built environment. Although no prior tourism research has directly addressed these concerns, the issue becomes increasingly relevant in light of the post-pandemic expansion of nature-based tourism and transformation nature-based destinations (Hall et al., Citation2020).

In the consolidated tourist region of Tatra and Podhale, place attachment proved to be a vital element in supporting conservation initiatives. However, neither place identity nor place dependence showed any association with local support for the national park in the Tatra Mountains. Our research indicates that only a connection to the local natural environment tends to foster more positive attitudes towards the TNP. The above findings suggest that understanding residents’ perceptions of protected areas requires taking into account their relationship with their local natural surroundings. It, however, contradicts the assumptions made by Huber and Arnberger (Citation2016) regarding the direct link between place attachment and local acceptance of protected areas.

Our study also offers nuanced insights into the effects of tourism on residents’ attitudes toward conservation measures, specifically those related to a national park. Interestingly, neither economic gains from tourism nor general support for tourism influenced the Podhale residents’ attitudes toward the Tatra National Park (TNP)Top of Form. Conversely, we discovered that residents who financially benefit from tourism are typically more likely to support it, corroborating earlier findings by Boley et al. (Citation2018). Yet, these economically advantaged residents are less likely to champion conservation efforts. This trend is consistent with previous debates suggesting that the expansion of a destination focused on natural attractions may paradoxically lessen the community's regard for these very natural resources. As tourism economic benefits grow in such locations, local enthusiasm for preserving nature wanes. For residents of Podhale who benefit financially from tourism, the local environment becomes secondary; their economic gains are not viewed as directly tied to the area's natural assets.

Again, the above result challenged our expectations. Namely, in line with the social exchange theory residents who benefit from tourism and support tourism in Podhale should also support TNP and more broadly nature conservation, because their benefits depend on the quality of local nature and the tourist attractiveness of the national park. Given the lack of significant relationship between the above noted economic benefits, support for tourism and attitudes towards TNP, we put forth that tourism may not be associated with this protected area (TNP) among residents of the Podhale region. Furthermore, benefits from tourism may not be perceived to linked to the quality of local nature in the destination, but instead, other tourism activities generate these economic benefits. Similarly, those who benefit from tourism are less likely to support nature conservation. Frankly, residents of Tatra and Podhale region do not recognize the contribution that TNP makes to tourism. The TNP is not viewed a tourism asset (for comparison, see: Balmford et al., Citation2009).

This line of thought is further supported by the observation that while residents who are pro-tourism also generally favor nature conservation efforts, their enthusiasm for tourism increases when they believe that the TNP attracts visitors. Additionally, residents who view TNP as an attractive feature for tourists in Tatra and Podhale are more likely to support both TNP and broader nature conservation initiatives. These findings underscore the importance of effectively communicating to residents about the pivotal role that local protected areas and natural environments play in drawing tourists, as suggested by prior studies (Baral & Heinen, Citation2007; Gadd, Citation2005). They also highlight the significance of cultivating positive interactions between local communities and Tatra National Park.

Our research challenges the notion that residents in well-developed nature-based tourist regions perceive protected areas as a catalyst for tourism, a view supported by earlier work (Lundmark et al., Citation2010). Contrary to this commonly accepted view (e.g. Allendorf, Citation2022; Becken & Job, Citation2014; Boyle & Green, Citation2016; Eagles et al., Citation2002; Goodwin, Citation2002; Heslinga et al., Citation2017; Idrissou et al., Citation2013; Snyman, 2014), nature-based tourism may no longer serve as a reliable basis for local support of protected areas in such mature destinations. The data indicate, however, that advocacy for Tatra National Park is significantly correlated with pre-existing inclinations toward conservation initiatives. Particularly, residents who support local conservation efforts are more likely to support the park's preservation efforts.

Pathways toward support for the national park

In accordance with the results of asymmetric modeling, place identity, nature bonding, and support for tourism are necessary components for positive attitudes toward the park. These elements are needed for residents to support TNP and should be included in future models of residents’ attitudes. In contrast, economic benefits from tourism are not linked to residents’ support of nature protection through the park. Ultimately, pathways leading to support for TNP and general nature conservation demonstrate that attitudes toward TNP and nature conservation are not the same.

This study provides important insights regarding the often-overlooked situation in which local communities may consider a local protected area to be a public authority over the land. These politicized constructions of protected areas undermine potential synergies between tourism development and nature conservation. Previously, Holmes (Citation2014) argued that many conflicts between locals and conservation authorities over protected areas are a result of rival attempts to define the boundaries of control and who should have rights to manage the land. In this respect, perceptions of TNP may also result from ongoing conflicts between the landowners and the park (Komorowska, Citation2000).

Conclusions

By combining insights from social exchange theory and place attachment, our research identifies how local residents’ conservation preferences are influenced by their emotional ties to the area and their opinions on tourism. This research carries both theoretical and practical ramifications.

From a theoretical standpoint, this investigation broadens the scope of social exchange theory by applying it to residents’ perceptions of protected areas in tourist-heavy localities, analyzed through a cost–benefit paradigm. While prior studies have primarily used SET to explore residents’ support for tourism itself (such as Ap, Citation1992; Strzelecka, Boley, et al., Citation2017;; Strzelecka, Rechinski, et al., Citation2017 Woosnam et al., Citation2009), we demonstrate that the same social exchange mechanisms can be applied to understand residents’ backing for local protected areas. In this context, social exchange theory supplements the framework of place attachment, as it focuses on how residents perceive the tourism-related benefits of a protected area, which in turn shapes their support for that area.

Contrary to the widely held view that tourism development positively influences attitudes towards national parks (Boyle & Green, Citation2016; Goodwin, Citation2002; Lockwood et al., Citation2005), our findings suggest that the context matters. Our study shows that tourism growth in the communities surrounding national parks impacts how these communities relate to protected areas (Stone et al., Citation2021). Additionally, these relationships are affected by the way these parks were initially set up. Like many other national parks around the world, TNP was established in a top-down manner with the primary goal of protecting local ecosystems by overlooking local land use planning and regional development projects (Hibszer, Citation2013; Mika et al., Citation2015). Therefore, to generate broader support for its operations in the contemporary context, parks like TNP need to find a way to communicate to residents their pivotal role as tourist asset of the region. In other words, for residents to support local protected areas, they first need to understand how these areas are beneficial to the tourism industry.

Limitations

An important limitation of the presented survey research is that it is a non-experimental approach used to gather information about the relationships that exist between variables in the population (Babbie, Citation1990). The survey design was used to depict perceptions in a moment of time rather than to study a long-term attitudinal change within the gateway communities as tourism developed in Zakopane county. As we were interested specifically in the relationship between mental constructs residents held at the time regarding the national park rather than their behaviors or behavioral intentions, we deemed this is the appropriate way to approach our research inquiry. The limitations and advantages of structural equation modeling are extensively discussed by Hair et al. (Citation2021).

Future research directions

While we demonstrated that residents may have difficulty recognizing the protected area's contribution to tourism in a consolidated nature-based tourism destination, the results provoke to a new way of thinking about the role of protected areas in tourism development and the actual effect of protected areas on the tourism growth. Further research can be conducted in several possible directions. First, we need to better understand when protected areas matter for tourism development to understand if compromising nature protection efforts by promoting protected area tourism is the right path towards sustainability. Second, we need to assess whether an extensive tourism infrastructure and development of diverse tourism attractions can undermine the significance of nature for tourism development and the symbiotic relationship between tourism and nature conservation. Third, in order to determine the effect of protected areas on tourism, it is necessary to employ a variety of methods, including big data analysis, field experiments. Using a survey method may not be sufficient to capture a holistic picture of tourism development around protected areas.

One reason for the discrepancy between our findings and prior studies might be that much of the existing research focused on emerging tourist destinations, framing protected areas as tools for luring visitors to less-visited locales and diversifying the local economy (Whitelaw et al., Citation2014). Conversely, our study focused on a region where nature-based tourism is already at a consolidated stage. Studying consolidated nature-based destinations surrounding protected areas will improve our understanding of the complex relationship between local communities and protected areas.

Supplemental Material

Download ()Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abukari, H., & Mwalyosi, R. B. (2020). Local communities’ perceptions about the impact of protected areas on livelihoods and community development. Global Ecology and Conservation, 22, e00909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e00909

- Allendorf, T. D., (2022). A global summary of local residents’ perceptions of benefits and problems of protected areas. Biodiversity and Conservation 31(2), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-022-02359-z

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Andrade, G. S., & Rhodes, J. R. (2012). Protected areas and local communities: An inevitable partnership toward successful conservation strategies? Ecology and Society, 17(4), 14. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-05216-170414

- Ap, J. (1992). Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 19(4), 665–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(92)90060-3

- Babbie, E. (1990) Survey research methods (2nd ed.) Wadsworth Publishing Co.

- Balmford, A., Beresford, J., Green, J., Naidoo, R., Walpole, M., & Manica, A. (2009). A Global Perspective on Trends in Nature-Based Tourism. PLoS Biology, 7(6), e1000144. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1000144.

- Baral, N., & Heinen, J. (2007). Resources use, conservation attitudes, management intervention and park-people relations in the Western Terai landscape of Nepal. Environmental Conservation, 34(1), 64–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892907003670

- Becken, S., & Job, H. (2014). Protected areas in an era of global–local change. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(4), 507–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.877913

- Bennetta, N. J., & Deardenc, P. (2014). Why local people do not support conservation: Community perceptions of marine protected area livelihood impacts, governance and management in Thailand. Marine Policy, 44, 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2013.08.017

- Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

- Boley, B. B., & Green, G. T. (2016). Ecotourism and natural resource conservation: The ‘potential’ for a sustainable symbiotic relationship. Journal of Ecotourism, 15(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2015.1094080

- Boley, B. B., McGehee, N. G., Perdue, R. R., & Long, P. (2014). Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.08.005

- Boley, B. B., Strzelecka, M., & Woosnam, K. M. (2018). Resident perceptions of the economic benefits of tourism: Toward a common measure. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 42(8), 1295–1314. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348018759056

- Boley, B. B., Strzelecka, M., Yeager, E. P., Ribeiro, M. A., Aleshinloye, K. D., Woosnam, K. M., & Mimbs, B. P. (2021). Measuring place attachment with The Abbreviated Place Attachment Scale (APAS). Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74, 101577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101577

- Brinberg, D., & Castell, P. (1982). A resource exchange theory approach to interpersonal interactions: A test of Foa's theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(2), 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.43.2.260

- Buckley, R., Brough, P., Hague, L., Chauvenet, A., Fleming, C., Roche, E., Sofija, E., & Harris, N. (2019). Economic value of protected areas via visitor mental health. Nature Communications, 10(1), 5005. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12631-6

- Budowski, G. (1976). Tourism and environmental conservation: Conflict, coexistence, or symbiosis? Environmental Conservation, 3(1), 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892900017707

- Chen, N. C., Hall, C. M., & Prayag, G. (2021). Sense of place and place attachment in tourism (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429279089

- Cheng, J. C.-H., & Monroe, M. C. (2012). Connection to nature: Children’s affective attitude toward nature. Environment and Behavior, 44(1), 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510385082

- Choi, H. Ch., & Murray, I. (2010). Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(4), 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903524852

- Cross, J. E. (2015), Processes of place attachment: An interactional framework. Symbolic Interaction, 38(4), 493–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.198

- Cundill, G., Bezerra, C. J., De Vos, A., & Ntingana, N. (2017). Beyond benefit sharing: Place attachment and the importance of access to protected areas for surrounding communities. Ecosystem Services, 28(Part B), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.03.011

- Devine-Wright, P. (2009). Rethinking NIMBYism: The role of place attachment and place identity in explaining place-protective action. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 19(6), 426–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1004

- Devine-Wright, P., & Howes, Y. (2010). Disruption to place attachment and the protection of restorative environments: A wind energy case study. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.01.008

- Draper, J., Woosnam, K. M., & Norman, W. C. (2011). Tourism use history: Exploring a new framework for understanding residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 50(1), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509355322

- Dziadowiec J. (2010). Góralskie reprezentacje, czyli rzecz o Podhalanach i ich kulturze, ZN TD UJ – Nauki Humanistyczne, 1, 48–71.

- Eagles, P. F. J., McCool, S. F., & Haynes, C. J. (2002). Sustainable tourism in protected areas: Guidelines for planning and management. IUCN Publications Unit. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851995892.0235

- Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2(1), 335–362. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.so.02.080176.002003

- Gadd, M. E. (2005). Conservation outside of parks: Attitudes of local people in Laikipia, Kenya. Environmental Conservation, 32(1), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892905001918

- Goodwin, H. (2002). Local community involvement in tourism around National Parks: Opportunities and constraints. Current Issues in Tourism, 5(3-4), 338–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500208667928

- Gosling, E., & Williams, K. (2010). Connectedness to nature, place attachment and conservation behaviour: Testing connectedness theory among farmers. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 298–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.01.005

- Goudriaan, Y., Prince, S., & Strzelecka, M. (2023) A narrative approach to the formation of place attachments in landscapes of expanding renewable energy technology. Landscape Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2023.2166911

- Goudy, W. J. (1990). Further consideration of indicators. Social Indicators Research 11(2), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00302748

- Gruber, J. S. (2010). Key principles of community-based natural resource management: A synthesis and interpretation of identified effective approaches for managing the commons. Environmental Management, 45(1), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-008-9235-y

- Gursoy, D., & Rutherford, D. G. (2004). Host attitudes toward tourism an improved structural model. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.008

- Gustafson, P. (2001). Meanings of place: Everyday experience and theoretical conceptualizations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 21(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2000.0185

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., & Ray, S. (2021). An introduction to structural equation modeling. In Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R. Classroom Companion: Business. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80519-7_1

- Hall, C. M., Scott, D., & Gössling, S. (2020). Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tourism Geographies, 22(3), 577–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2020.1759131

- Halpenny, E. A. (2010). Pro-environmental behaviours and park visitors: The effect of place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.04.006

- Hernández, V., Martín, A. M., Ruiz, C., & del Carmen Hidalgo, M. (2010). The role of place identity and place attachment in breaking environmental protection laws. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 281–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.01.009

- Heslinga, J., Groote, P., & Vanclay, F. (2017). Strengthening governance processes to improve benefit-sharing from tourism in protected areas by using stakeholder analysis. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27, 773–787. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1408635

- Hibszer, A. (2008). Konflikty “człowiek – przyroda” w polskich parkach narodowych: zarys problemu, Geographia. Studia et Disertationes, 30, 29–46.

- Hibszer, A. (2013). Parki narodowe w świadomości i działaniach społeczności lokalnych. Uniwersytet Śląski.

- Holmes, G. (2014). Defining the forest, defending the forest: Political ecology, territoriality, and resistance to a protected area in the Dominican Republic. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 53, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.01.015

- Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. Harcourt, Brace & World.

- Huber, M., & Arnberger, A. (2016). Opponents, waverers or supporters: The influence of place-attachment dimensions on local residents’ acceptance of a planned biosphere reserve in Austria. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 59(9), 1610–1628. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2015.1083415

- Idrissou, L., van Paassen, A., Aarts, N., Vodouhè, S., & Leeuwis, C. (2013). Trust and hidden conflict in participatory natural resources management: The case of the Pendjari national park (PNP) in Benin. Forest Policy and Economics, 27, 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2012.11.005

- Jackson, M. M., & Naughton-Treves, L. (2012). Eco-bursaries as incentives for conservation around Arabuko-Sokoke Forest, Kenya. Environmental Conservation, 39(4), 347–356. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892912000161

- Jurowski, C., & Gursoy, D. (2004). Distance effects on residents’ attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(2), 296–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.12.005

- Kaján, E. (2014). Community perceptions to place attachment and tourism development in Finnish Lapland. Tourism Geographies, 16(3), 490–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2014.941916

- Kinnaird, M., & O’Brien, T. (1996). Ecotourism in the tangkoko DuaSudara nature reserve: Opening pandora' box? Oryx, 30(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605300021402

- Kiss, A. (2004). Is community-based ecotourism a good use of biodiversity conservation funds? Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 19(5), 232–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.010

- Komorowska, K. A. (2000), Świadomość ekologiczna górali Podhalańskich a ich postawy wobe Tatrzańskiego Parku Narodowego. Studia Regionalne i Lokalne, 4(4), 133–151.

- Kroh, A. (2002). Tatry i Podhale, Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, Wrocław.

- Kruger, O. (2005). The role of ecotourism in conservation: Panacea or Pandora’s box? Biodiversity and Conservation, 14(3), 579–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-004-3917-4

- Kucina, W. (2007). Konflikt społeczny na tle własności gruntów w Tatrzańskim Parku Narodowym [Social ownership in the Tatra Mountains National Park]. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Geographica Socio-Oeconomica, 8, 185–210.

- Lalicic, L., & Garaus, M. (2022). Tourism-Induced place change: The role of place attachment, emotions, and tourism concern in predicting supportive or oppositional behavioral responses. Journal of Travel Research, 61(1), 202–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520967753

- Lawler, E. J., & Shane, R. (1999). Bringing emotions into social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 25(1), 217–244. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.217

- Lee, E. B. (2008). Environmental attitudes and information sources among African American college students. The Journal of Environmental Education, 40(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.40.1.29-42

- Lindberg, K., Enriquez, J., & Sproule, K. (1996). Ecotourism questioned. Annals of Tourism Research, 23(3), 543–556. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(95)00074-7

- Lockwood, J. L., Cassey, P., & Blackburn, T. (2005). The role of propagule pressure in explaining species invasions. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 20(5), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2005.02.004

- Low, S. M., & Altman, I. (1992). Place attachment. In I. Altman & S. M. Low (Eds.), Place Attachment. Human Behavior and Environment (Vol. 12). Boston, MA: Springer.

- Lundmark, L. J. T., Fredman, P., & Sandell, K. (2010). National parks and protected areas and the role for employment in tourism and forest sectors: A Swedish case. Ecology and Society, 15(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-03175-150119

- Marcus, R. R. (2001). Seeing the forest for the trees: Integrated conservation and development projects and local perceptions of conservation in Madagascar. Human Ecology, 29(4), 381–397. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013189720278

- Marshall, N. A., Marshall, P. A., Abdulla, A., & Rouphael, T. (2010). The links between resource dependency and attitude of commercial fishers to coral reef conservation in the Red Sea. AMBIO, 39(4), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-010-0065-9

- McGehee, N. G., & Andereck, K. (2004). Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268234

- Mehta, J., Heinen, J. (2001). Does community-based conservation shape favorable attitudes Among locals? An empirical study from Nepal. Environmental Management 28(2), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002670010215

- Mika, M. (2023). Diagnoza ekonomicznego oddziaływania Tatrzańskiego Parku Narodowego na gospodarkę lokalną. Raport z badań. Kraków–Zakopane.

- Mika, M., Zawilińska, B., & Pawlusiński, R. (2015). Park narodowy a gospodarka lokalna. Model relacji ekonomicznych na przykładzie Babiogórskiego Parku Narodowego. IGiGP UJ.

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2010). Modeling community support for a proposed integrated resort project. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(2), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903290991

- Nyaupane, G. P., & Poudel, S. (2011). Linkages among biodiversity, livelihood, and tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1344–1366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.03.006

- Oldekop, J. A., Holmes, G., Harris, W. E., & Evans, K. L. (2016). A global assessment of the social and conservation outcomes of protected areas. Conservation Biology, 30(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12568

- Olya, H. G. T. (2020). Towards advancing theory and methods on tourism development from residents’ perspectives: Developing a framework on the pathway to impact. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1843046

- Perdue, R. R., Long, P. T., & Allen, L. (1990). Resident support for tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 17(4), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(90)90029-Q

- Proshansky, H., Fabian, A., & Kaminoff, R. (1983). Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(83)80021-8

- Radwańska-Paryska, Z., & Paryski, W. H. (2004). Wielka Encyklopedia Tatrzańska [The Great Encyklopedia of the Tatra Mts]. Wydawnictwo Górskie.

- Ragin, C. C. (2009). Qualitative comparative analysis using fuzzy sets (fsQCA). Configurational comparative methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and Related Techniques, 51, 87–121.

- Ramkissoon, H., & Nunkoo, R. (2011) City image and perceived tourism impact: Evidence from Port Louis, Mauritius. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 12(2), 123–143, https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2011.564493

- Raymond, Ch. M., Brown, G., & Weber D. (2010). The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(4), 422–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.08.002

- Richter, N. F., Schubring, S., Hauff, S., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2020). When predictors of outcomes are necessary: Guidelines for the combined use of PLS-SEM and NCA. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 120(12), 2243–2267. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-11-2019-0638

- Rihoux, B., & Ragin, C. C. (2009). Configurational comparative methods: Qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques (Vols. 1–51). SAGE.

- Ross, S., & Wall, G. (1999). Evaluating ecotourism: The case of North Sulawesi, Indonesia. Tourism Management, 20(6), 673–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(99)00040-0

- Sah, J., & Heinen, J. (2001). Wetland resource use and conservation attitudes among indigenous and migrant peoples in Ghodaghodi Lake area, Nepal. Environmental Conservation, 28(4), 345–356. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892901000376

- Scannell, L., & Gifford, R. (2010). Defining place attachment: A tripartite organizing framework, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.006

- Sekhar, N. U. (2003). Local people's attitudes towards conservation and wildlife tourism around Sariska Tiger Reserve, India. Journal of Environmental Management, 69(4), 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2003.09.002

- Sharpley, R. (2014). Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tourism Management, 42, 37-49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.10.007

- Sirivongs, K., & Tsuchiya, T. (2012). Relationship between local residents’ perceptions, attitudes and participation towards national protected areas: A case study of Phou Khao Khouay National Protected Area, central Lao PDR. Forest Policy and Economics, 21, 92–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forpol.2012.04.003

- Spenceley, A., & Snyman, S.. (2017). Protected area tourism: Progress, innovation and sustainability. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 17(1), 3–7.

- Stedman, R. C. (2002). Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environment and Behavior, 34(5), 561–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502034005001

- Stedman, R. C. (2003). Is It really just a social construction?: The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place. Society & Natural Resources, 16, 671–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920309189

- Stem, C. J., Lassoie, J. P., Lee, D. R., & Deshler, D. J. (2003). How “Eco” is ecotourism? A comparative case study of ecotourism in Costa Rica. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 11(4), 322–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580308667210

- Stone, M., & Wall, G. (2004). Ecotourism and community development: Case studies from Hainan,China. Environmental Management, 33(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-003-3029-z

- Stone, M. T., Stone, S. L., & Nyaupane, G. P. (2021). Theorizing and contextualizing protected areas, tourism and community livelihoods linkages. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.2003371

- Strzelecka, M., Boley, B. B., & Strzelecka, C. (2017). Empowerment and resident support for tourism in rural Central and Eastern Europe (CEE): The case of Pomerania, Poland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 25(4) 554–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2016.1224891

- Strzelecka, M., Prince, S., & Bynum Boley, B. (2021). Resident connection to nature and attitudes towards tourism: Findings from three different rural nature tourism destinations in Poland. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1995399

- Strzelecka, M., Rechciński, M., & Grodzińska-Jurczak, M. (2017). Using PP GIS interviews to understand residents’ perspective of European ecological network Natura 2000. Tourism Geographies, 19(5), 848–877. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1377284

- Stylidis, D., Biran, A., Sit, J., & Szivas, E. M. (2014). Residents’ support for tourism development: The role of residents’ place image and perceived tourism impacts. Tourism Management, 45, 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.05.006

- Sutton, W., Jr. (1967). Travel and understanding: Notes of the social structure of tourism. Journal of Comparative Sociology, 8, 217–223.

- Thibaut, J. W., & Kelley, H. H. (1959). The social psychology of groups. Wiley.

- Tuan, Y. F. (1974). Space and place: Humanistic perspective. Progress in Geography, 6, 211–252

- Uysal, M., Noe, F., & McDonald, C. D. (1994). Environmental attitude by trip and visitor characteristics: U.S. Virgin Islands National Park. Tourism Management, 14(4), 284–294.

- Vaske, J. J., & Kobrin, K. C. (2001). Place attachment and environmentally responsible behavior. The Journal of Environmental Education, 32(4), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958960109598658

- Waylen, K. A., Fisher, A., McGowan, P. J. K., Thirdgood, S. J., & Milner-Gulland, E. J. (2010). Effect of local cultural context on the success of community-based conservation interventions. Conservation Biology, 24(4), 1119–1129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523739.2010.01446.x

- Whitelaw, P. A., Brian, E., King, M., & Tolkach, D. (2014). Protected areas, conservation and tourism – financing the sustainable dream. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(4), 584–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.873445

- Williams, D. R., Patterson, M. E., Roggenbuck, J. W., & Watson, A. E. (1992). Beyond the commodity metaphor: Examining emotional and symbolic attachment to place. Leisure Sciences, 14(1), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409209513155

- Williams, D. R., & Vaske, J. J. (2003). The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach. Forest Science, 49(6), 830–840.

- Woosnam, K. M., Norman, W. C., & Ying, T. (2009). Exploring the theoretical framework of emotional solidarity between residents and tourists. Journal of Travel Research, 48(2), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287509332334

- Wynveen, C. J., Woosnam, K. M., Keith, S. J., & Barr, J. (2021). Support for wilderness preservation: An investigation of the roles of place attachment and environmental worldview. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 35, 100417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2021.100417

Appendix

Confirmatory factor analysis

CFA aims to assess the measurement model and ensure that the model has a good model fit and that the individual scales within the model are constructed and valid before testing structural relationships (Hair et al., Citation2021). Construct validity assesses how well a latent construct's items measure the construct. It is comprised of convergent validity, discriminant validity, and nomological. Convergent validity pertains to how well a latent construct's items converge to measure the latent construct. A measure can be considered to have convergent validity when its factor loadings are above 0.5, its construct reliability coefficient is above 0.7, and the amount of variance it explains is above 50% (Hair et al., Citation2021). Discriminant validity ensures that the constructs within the model are unique and do not measure the same thing. Discriminant validity is assessed by comparing the squared correlation between constructs with the average variance explained (AVE) by constructs. If AVE is higher than the squared correlation, it can be assumed that the constructs are unique because they explain the unique variance that they share (Hair et al., Citation2021).

Regarding model fit, CFI estimates were above 0.90, and RMSEA estimates were below 0.08. Convergent validity was demonstrated based on all factor loadings being above 0.5 and significant at the .001 level, AVEs being above 50%, and Construct Reliability estimates being above 0.70 for each construct. ().

Table A1. Confirmatory factor analysis.

Table A2. Discriminant validity assessment.