ABSTRACT

During any crisis, how a company communicates will determine how much reputational capital is spent and how quickly the company can recover. Extending the Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) to hotel websites and social media, this paper investigates Swiss hotels’ messages during this crisis to repair their image, bolster their reputation, and attract customers back to Swiss destinations. From June 2020 to August 2021, messages from Swiss independent 4- and 5-star hotels were mined, and semantic network analysis, sentiment analysis, and an analysis of SCCT strategies were employed to investigate hoteliers’ messages during the pandemic. Hoteliers adopted different strategies between hotel website (dominated by corrective action) and social media (renewal). Hoteliers tried to create positive emotions as detected through sentiment analysis and the wide use of exclamation points. Guest was the most popular theme and concept from the semantic analysis. The emphasis on guests and positive emotion indicates the humanness of the communicated message.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic can be categorized as the penultimate crisis that affected all industries worldwide to different extents. While industries such as online shopping and delivery services thrived, most industries saw their business model tested and their profits decline. One particularly hard-hit industry was tourism, more specifically, hospitality. Travel came to a halt, airplanes were grounded, and many hotels closed or drastically reduced their services. Official travel restrictions, event cancellations, travellers’ fear of risk (Gonzalez et al., Citation2021), stay-at-home orders (Villace-Molinero et al., Citation2021), and social distancing (Yeh, Citation2021) caused a severe disruption in what was predicted to be a record year for international travel. Further, the pandemic triggered ‘travel fears’ and even travel avoidance (Xie et al., Citation2021). No one imagined the massive impact COVID-19 would have (and continues to have) on travel behaviour (Jingyi et al., Citation2020), and hotels are currently attempting to regain customer trust.

For Switzerland, the closing, opening, closing, and opening again became a part of everyday life. Starting in March 2020, Swiss hotels were faced with changing sanitary measures and inconsistent communication from the Swiss government in how they could conduct business. In Switzerland, the tourism industry is one of the largest export industries in Switzerland with 4.4% of export revenue. According to the official statistics published in February 2020, Switzerland welcomed 1,343,000 tourists. In March 2020, this number dropped to 496,000 tourist arrivals and, in April 2020, dropped even further to 51,000 tourist arrivals (Switzerland tourist arrivals, Citationn.d.). In comparing tourism numbers from 2019, in March 2020, hotels recorded 68% fewer foreign tourists than the same period the year before (Swiss tourism numbers crash, Citation2020). For a year that promised to be a lucrative one for the tourism industry, the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis completely changed travel plans and, subsequently, the tourism industry worldwide.

To analyse this crisis and mitigate the effects of the pandemic on the hospitality industry, this paper examines what Swiss 4 and 5-star hotels communicated to their stakeholders through their official websites and Facebook pages over a 14-month period (from June 2020 to August 2021). The purpose is to gauge whether Swiss hotels effectively applied Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) in their messages during the peaks and waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. While many previous studies have investigated the communication channels used during times of crisis, scant literature has explicitly focused on the messages hoteliers communicated during a crisis. To this purpose, this study analyses the messages (what) posted on official channels (where) to gauge their effectiveness (how) in protecting their reputation and reassuring travellers that it is safe to come back to Switzerland.

Theoretical background

Theory of planned behaviour

The Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) introduced by Ajzen in Citation1991 has been cited in many studies in which risk was assessed (Jingyi et al., Citation2020; Li et al., Citation2020; Yeh, Citation2021). TPB is the dominant framework for explaining human behaviour, including travel behaviour, and includes the interaction between beliefs, attitudes, subjective norms, and behavioural control that determines intention to do something (Ajzen, Citation1991; Jingyi et al., Citation2020). According to TPB, attitudes can be defined as the degree to which an individual positively or negatively assesses behaviour; subjective norms include the perceived social obligation to act; perceived control behaviour highlights the (in)capabilities of performing a behaviour; and behavioural intention suggests that an action will take place (Ajzen, Citation1991). For the hospitality and tourism industries, specifically, this behavioural intention revolves around the intention to travel or commitment to travel (Jingyi et al., Citation2020; Li et al., Citation2020; Villace-Molinero et al., Citation2021).

Nonetheless, the belief that a destination could be risky will affect travellers’ intention to visit as travellers are extremely sensitive to risk messages and the possibility of danger, harm, or losses associated with the travel (Xie et al., Citation2021). In travel, risk perception is a subjective assessment of travel security and is based on uncontrollable and accumulative factors during the travel experience (Jingyi et al., Citation2020). In the case of the COVID-19 pandemic, travel decisions were framed by official travel restrictions, event cancellations, and travellers’ fear of risk (Gonzalez et al., Citation2021). Further, their risk evaluation was exacerbated by mixed messages, misinformation, constantly changing regulations, and the different perceptions of the level of risk that COVID-19 posed (Villace-Molinero et al., Citation2021). When facing a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, travellers may have been driven by affective risks or those associated with an emotional response rather than cognitive risk that is linked to the probability that the risk is present (Jingyi et al., Citation2020). For reassurance, many travellers sought information from governmental or health sources to ensure their safety before making decisions to complete a booking or spend money on travel (Roth-Cohen & Lahav, Citation2021; Xie et al., Citation2021). Once they gathered this information about the destination to make their proper risk assessment, some travellers chose to cancel, delay, alter, or keep their plans (Villace-Molinero et al., Citation2021). After evaluating the risk as communicated from official sources, travellers then seek further information from private sources (such as testimonials from friends or family) or online information (via social media or the Internet) (Villace-Molinero et al., Citation2021).

Situational crisis communication theory

Crisis communication focuses on the prevention and reduction of harm (Wong et al., Citation2021). When done effectively, crisis communication can reduce the risk perceptions and long-lasting negative impacts on a destination (Xie et al., Citation2021). This effective risk communication can protect a company’s reputation in times of crisis (such as the COVID-19 pandemic) (Kim et al., Citation2021) and help build confidence to make travel decisions and encourage cooperative decision-making (Xie et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, in a pandemic that was so broad and inclusive, no one company or industry ‘owned’ the crisis (Jong, Citation2020); thus, trying to communicate about it effectively created an unprecedented challenge. Although it was a global crisis, the messages needed to be adapted to each sector and industry (Gonzalez et al., Citation2021) by considering the timeliness, audience, sources, and channels (Xie et al., Citation2021). Further, a balance needed to be found between the alarming tone of the situation’s urgency and the actions the public must take to stay safe and healthy (Jong, Citation2020). While hotels could have fostered consumer confidence by reassuring their customers, many hotels were rather ‘sluggish’ and hesitant to communicate about the COVID-19 pandemic (Wong et al., Citation2021; Zizka et al., Citation2021). Many companies, particularly hospitality and tourism companies, lacked interactive dialogue with their customers and missed the opportunity to position themselves as ‘victims’ and show their ‘humanness’ in times of crisis (Camilleri, Citation2020; Zizka et al., Citation2021). To mitigate risk, they needed to reassure their customers that they have clean and safe spaces to enjoy (Jiminez-Barreto et al., Citation2021) through new cleaning technology or further emphasis on hygiene (Salem et al., Citation2021). Nonetheless, during the past year, these hospitality and tourism companies struggled to understand what was going on before communicating it (Jong, Citation2020). What they actually needed was an effective strategy for communicating during a crisis.

Crises are negative events that lead stakeholders to assess a company’s responsibility for the crisis (Coombs, Citation2007). After all, no company is immune to crisis (Claeys et al., Citation2010). For this reason, Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) was developed (Coombs, Citation1995). SCCT is based on the strategies companies can employ to mitigate the effects of a crisis and retain reputational capital (Coombs, Citation1995; Citation2007; Citation2017; Coombs & Holladay, Citation2002). Coombs and Holladay (Citation2002) defined crises as ‘unpredictable events that can disrupt an organization’s operations and threaten to damage organizational reputation’ (p. 2). Nevertheless, the immediate priority is protecting the stakeholders from harm, not protecting the company’s reputation (Coombs, Citation2007; Kim & Liu, Citation2012; Stewart & Young, Citation2018). Further, when the crisis involves public safety, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, information on how customers can protect themselves is more important than reputational concerns (Coombs & Holladay, Citation2002).

SCCT proposes numerous strategies to employ based on the severity and type of crisis a company is facing. It is based on how stakeholders perceive a company’s responsibility for the crisis. Two factors affect the initial assessment of crisis responsibility: (1) severity (i.e. amount of damage generated by the crisis) and (2) performance history (i.e. a company’s crisis history and how well they have treated their stakeholders in the past) (Coombs & Holladay, Citation2002). The company’s previous crisis history and prior relationship reputation are called ‘intensifying factors’ as they increase the initial assessment of crisis responsibility (Coombs, Citation2007). For an accidental or preventable crisis, trust is eroded (Dulaney & Gunn, Citation2017), and companies must employ numerous SCCT strategies beyond the base response (Coombs, Citation1995; Citation2007; Citation2017). While a victim crisis, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, usually requires only a minimal response, i.e. a base response of instructing and adjusting information (Coombs, Citation1995; Citation2007; Citation2017), messages about hygiene, safety, protective measures, and current COVID-19 regulations did not suffice (Zizka et al., Citation2021). Hoteliers also needed to communicate upbeat messages to encourage travellers to return (Zizka et al., Citation2021).

According to Coombs and Holladay (Citation2002), ‘the greater the crisis responsibility generated by the crisis, the more accommodative the crisis response strategies must be’ (p. 171). Beyond the base response, the initial list of SCCT strategies included: Attack the attacker, Denial, Excuse, Victimization, Justification, Ingratiation, Corrective actions, and Full apology (Coombs, Citation1995). A summary of each strategy can be found in .

Table 1. SCCT strategies.

This list has been expanded further in more recent research projects with the addition of Scapegoating (Ki & Nekmat, Citation2014), Mortification (Cheng, Citation2018), Enhancing (Cheng, Citation2018; Kim & Liu, Citation2012), Transferring (Cheng, Citation2018; Kim & Liu, Citation2012; Schroeder & Pennington-Gray, Citation2015), Ignoring (Kim & Liu, Citation2012), and Renewal (Ulmer & Sellnow, Citation2002). When the company is a victim of the crisis like with COVID-19, they can use Renewal, Ingratiation, and Victimage. In an earlier study with the same hotels, Zizka et al. (Citation2021) confirmed that Swiss hotels employed the Victimage strategy, followed by Ingratiation during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Though Renewal is suggested in the expanded SCCT strategies, Swiss hotels did not employ that strategy during the first wave and closure of their hotels. The results of the current study, though, reveal a strong implementation of the Renewal strategy since June 2020.

Communicating crisis on social media

Previous studies have shown that the hospitality and tourism industries have not been proactive on one of the most commonly used channels, social media (Barbe & Pennington-Gray, Citation2018; Schroeder et al., Citation2013; Veil et al., Citation2011). While hospitality and tourism companies have been encouraged to use social media for destination and crisis management purposes, many do not consider how frequently their customers will turn to social media to seek information in times of crisis (Schroeder et al., Citation2013). Barbe and Pennington-Gray (Citation2018) posited the possibility that hotels may be afraid of drawing negative attention to themselves; they may fear that if they communicate about crises, they will be seen in a negative light. However, as hospitality and tourism stakeholders are already using social media to post comments or images during their travels or at their destinations (Schroeder et al., Citation2013), avoiding it is no longer an option (Veil et al., Citation2011). The hospitality and tourism industries may fear that stakeholders will hold a dialogue about the crisis that they cannot control (Veil et al., Citation2011) or that an ineffective message on social media could inflict more significant reputational damage on their reputation (Ki & Nekmat, Citation2014). Hospitality and tourism companies may worry that tourism demand will decrease if they communicate about the crisis and its risks (Barbe & Pennington-Gray, Citation2018). They may believe that by simply mentioning the crisis, i.e. COVID-19, the risk perception will increase (Barbe & Pennington-Gray, Citation2018), and these perceptions will negatively affect travel decision-making (Schroeder & Pennington-Gray, Citation2015). Nonetheless, the research suggests that effective communication during the time of crisis will be perceived more positively than scant or no information (Barbe & Pennington-Gray, Citation2018; Zizka et al., Citation2021); thus, companies must communicate where their customers seek information.

However, communicating with customers through the official website is ineffective. Customers rarely go to the official website to gather information (Austin et al., Citation2012); instead, they go to the website to book their trip. Hence, it may be futile to communicate about crises uniquely on the corporate website (Zizka et al., Citation2021). Further, social media channels offer companies a platform to reach, inform, and motivate audiences (Kwok et al., Citation2021; Park et al., Citation2019; Stewart & Young, Citation2018; Zhang et al., Citation2022). As the research suggests that effective communication during the time of crisis will be perceived more positively than scant or no information (Barbe & Pennington-Gray, Citation2018; Zizka et al., Citation2021), companies must communicate where their customers seek information.

Methodology

Data collection and sampling

The study was based on qualitative content analysis of Swiss 4- and 5-star hotels’ official websites and Facebook pages. The study began by seeking an official list of the 4- and 5-star hotels in Switzerland; this resulted in 220 hotels. Hotels that were affiliated with a chain or had no Facebook page were eliminated. The numbers of hotels reduced to 98. From this number, many hotels closed for substantial periods or did not communicate at all during the 14 months (from June 2020 to August 2021) used for this study. The final number of Swiss 4- and 5-star hotels was 48. The research team combed the official website and Facebook pages for each hotel for COVID-19 messages. The keywords chosen for the search were ‘COVID-19’, ‘Coronavirus’, and ‘pandemic’.

Qualitative content analysis–semantic analysis

Qualitative content analysis was conducted to illustrate the relationships between words and the frequency of words or phrases within the messages. This methodology is frequently employed in crisis-related research focusing on image repair (Avraham, Citation2020) or reputation repair. Further, it is a standard method utilized in the tourism sector for interpreting all types of messages. Previous studies include content analysis from newspapers, TV channels, tourism office webpages (Salem et al., Citation2021), the media (Avraham, Citation2020), press releases (Wong et al., Citation2021), news articles (Cheng & Edwards, Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2021), Facebook and websites (Zizka et al., Citation2021), and Facebook and Twitter (Azer et al., Citation2021). While these studies employed diverse topic modelling methods or software to conduct their analysis, numerous hospitality and tourism studies have chosen the Leximancer software as an alternative to analyse their data (Cheng & Edwards, Citation2019; Kazeminia et al., Citation2015; Liu et al., Citation2018; Pearce & Wu, Citation2016; Phi, Citation2020; Sotiriadou et al., Citation2014; Trinh & Ryan, Citation2017; Tseng et al., Citation2014; Ye et al., Citation2019; Yeh, Citation2021). Some examples include research that investigates messages communicated through blogs (Tseng et al., Citation2014), the news media (Cheng & Edwards, Citation2019; Phi, Citation2020), exploratory interviews (Sotiriadou et al., Citation2014), and governmental communications through the media or Tweets (Liu et al., Citation2021; Yeh, Citation2021).

While Leximancer allows researchers to explore the data promptly with the list of concepts emerging automatically from the text without the need for researcher input, it is argued that the lack of the researchers’ manipulation of the data can lead to difficulties in comprehension and interpretation of the output (Smith & Humphreys, Citation2006; Sotiriadou et al., Citation2014). However, Phi (Citation2020) posits that the automated results of the key concepts and the subsequent visual maps displaying them can reduce bias and increase reliability. In one study, Smith and Humphreys (Citation2006) evaluated Leximancer on its face validity, stability, reproductivity, and correlative validity. Further, Tseng et al. (Citation2014) concluded that the application of Leximancer provided a more comprehensive picture of the topic by combining visual diagrams and charts with lexical concepts than other content analysis programmes which only present word frequencies and connections.

In our study, we chose Leximancer (edition 5.0), a text mining software, to determine the presence and frequency of co-occurrence of words and concepts and provide a visual representation of the most frequently used terms (Cheng & Edwards, Citation2019; Liu et al., Citation2018; Phi, Citation2020; Sotiriadou et al., Citation2014; Tseng et al., Citation2014; Yeh, Citation2021). Leximancer first identifies the frequencies of co-occurrence words, then uses the bootstrapping process to develop a thesaurus. Leximancer denotes the thesaurus as ‘concepts’. In the following stage, the thesaurus (or concepts) is used as classifiers to re-classify the texts, and creates a concept index, a concept co-occurrence matrix, and clusters the results into ‘themes’ (Smith & Humphreys, Citation2006). Leximancer includes thesaurus learning algorithm, concept bootstrapping algorithm, term co-occurrence algorithm, nonlinear clustering algorithm, stochastic algorithm, and classification algorithm (Smith & Humphreys, Citation2006). In terms of algorithms used by Leximancer, the listed algorithms in the default setting were used for this study.

In Leximancer, a concept is described as a collection of related words expressed throughout the text. Seed words are defined to be the starting point of a concept. The model then evolves through a machine-learning process turning seed words into a complete thesaurus generating emerging concepts that are word like or (proper) name-like (Leximancer, Citation2021). According to Leximancer User Guide,

The concepts are clustered into higher-level ‘themes’ when the map is generated. Concepts that appear together often in the same pieces of text attract one another strongly, and so tend to settle near one another in the map space. The themes aid interpretation by grouping the clusters of concepts and are shown as colored circles on the map.

The process of analysis involved two stages. Firstly, the raw data collected from hotels’ websites and Facebook pages was cleaned to allow for uniform processing. The cleaning process involved homogenizing formats (e.g. different capitalizations or inconsistent paragraphing). Names and job titles were also removed under the condition that they were not embedded in relevant sections of the text. The output was formatted in sentence case, with one paragraph corresponding to one Facebook message or website section. Secondly, the cleaned data was analysed using Leximancer software (edition 5.0). Default settings were used and each data set was run three times, with no manipulation, Top 10 concepts manipulated, and all concepts manipulated. The data was also run separately as Facebook only, website only, and Facebook and websites combined. Through the Concept Seed Editor, merged concepts for Facebook and website posts included: Area & Areas, Guest & Guests, Mask & Masks, Restaurant & Restaurants, and Room & Rooms.

Once semantic analysis was complete, in a second stage, the most common concepts and words were analysed through their sentiment analysis via the Monkeylearn software. In a final stage, all of the comments were manually coded to reflect the SCCT strategies employed during this period. Through this 3-step process, a holistic picture of hoteliers’ crisis communication and its subsequent effects emerges and lends itself to interpretation and recommendations for future crisis communications.

Sentiment analysis

Like semantic analysis, sentiment analysis has grown in popularity in tourism and hospitality research (Alaei et al., Citation2019; Flores-Ruiz et al., Citation2021; Hao et al., Citation2020; Obembe et al., Citation2021). For example, Obembe et al. (Citation2021) used sentiment analysis to investigate tourists’ perceptions of tweets and news articles, and Flores-Ruiz et al. (Citation2021) studied tourists’ sentiment of messages posted on Twitter. Several studies applied sentiment analysis to Big Data gathered from the Internet through blogs, reviews, or news articles (Alaei et al., Citation2019; Hao et al., Citation2020). This method continues to grow due to its many benefits, such as lower costs (i.e. greater affordability for small-scale properties), reliability, and accessibility (i.e. free software such as RStudio, Knime, or Monkeylearn) (Flores-Ruiz et al., Citation2021). Further, sentiment analysis can ‘bring order to the chaos of human language’ (‘Natural language processing’, Citation2022) by using technology that can be trained for this task with none of the human prejudices nor biases.

Several groups of scholars have evaluated Monkeylearn. Monkeylearn has been evaluated by Accuracy, a key quality indicator for sentiment analysis (Fu et al., Citation2019; Hao et al., Citation2020; Hao et al., Citation2021). Further, researchers have cited the accuracy of Monkeylearn in separate studies as 63% (Contreras et al., Citation2021) or 57% respectively (Contreras et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, Monkeylearn (60%) outperformed Haven on demand (35%) and Standford CoreNLP (40%) in sentiment accuracy (Wang et al., Citation2017). Thus, the accuracy of using Monkeylearn has been confirmed in previous studies as a reliable software for sentiment analysis.

Nonetheless, there are several drawbacks to using sentiment analysis automated software. First, sentiment analysis is highly dependent on research domains and its classification accuracy for specific areas of research such as tourism and hospitality. Second, most hospitality and tourism studies focus on user-generated content, predominantly opinion-based (Hao et al., Citation2020). Sentiment analysis used with other types of content may not be as reliable. Finally, Alaei et al. (Citation2019) found that most sentiment analysis methods perform better in classifying positive sentences than negative or neutral sentences. This could suggest a bias to communicate positively despite the circumstances. Regardless of these drawbacks, researchers have promoted sentiment analysis as an essential research venue that could shape a new research paradigm for tourism (Alaei et al., Citation2019; Hao et al., Citation2020).

Sentiment analysis, also known as opinion mining, is one of the most popular natural language processing (NLP) used to identify different sentiments and polarities in texts (‘Natural language processing’, Citation2022). In sum, sentiment analysis refers to the use of computational linguistics and NLP to analyse text and identify its subjective information (Alaei et al., Citation2019). It allows machines to break down and interpret human language and extract meaning from text and speech (‘Natural language processing’, Citation2022). These machines are trained to make associations between specific input and its corresponding output (‘Natural language processing’, Citation2022). Sentiment analytics represents a polarity (i.e. positive and negative) classification problem (Alaei et al., Citation2019; Flores-Ruiz et al., Citation2021; Hao et al., Citation2020; Obembe et al., Citation2021). The sentiment polarity value ranges from −1 to +1, with zero representing neutral sentiments. Anything less than 0 represents negative sentiments, and greater than 0 is positive (Alaei et al., Citation2019; Flores-Ruiz et al., Citation2021; Hao et al., Citation2020; Obembe et al., Citation2021).

In terms of domains, the Monkeylearn software has specific classifiers for general sentiment analysis which we decided to use because it classifies message sentiment into positive, negative, and neutral. In our study, the data had already been retrieved, extracted, filtered, and cleaned in the first stage of our study (the semantic analysis). Thus, we could upload our clean data onto the Monkeylearn platform directly to run the sentiment analysis. Monkeylearn adopts a supervised machine learning approach, and uses support vector machine, naïve Bayes classifier, and linear regression in the programme. Like the semantic analysis through Leximancer, we also ran the sentiment analysis in three ways: Facebook alone, websites alone, and Facebook and websites together. Upon receiving the results, the research team recorded the sentiment classification, frequencies, and confidence level.

SCCT strategies

Many tourism and hospitality studies on crisis communication have applied SCCT strategies to company messages (Kwok et al., Citation2021; Liu-Lastres et al., Citation2020; Moller et al., Citation2018; Ou & Wong, Citation2021; Park et al., Citation2019; Scheiwiller & Zizka, Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2022). While some studies focused on natural disasters, such as tropical cyclones in Fiji (Moller et al., Citation2018) or Hurricane Irma (Park et al., Citation2019), these articles preceded the Covid-19 pandemic. The more recent studies have focused on communication during health crises, mainly related to the Covid-19 pandemic, in hotels (Kwok et al., Citation2021; Liu-Lastres et al., Citation2020; Zizka et al., Citation2021) and the airline industry (Ou & Wong, Citation2021; Scheiwiller & Zizka, Citation2021). Several studies highlighted the importance of social media without directly applying SCCT strategies (Moller et al., Citation2018; Park et al., Citation2019). Of the articles that applied SCCT to tourism during the Covid-19 pandemic, Liu-Lastres et al. (Citation2020) found enhancing was the most commonly used strategy; Kwok et al. (Citation2021) cited reminder, ingratiation, and victimage, and Scheiwiller and Zizka (Citation2021) reported instructing and adjusting crisis communication strategies.

For the SCCT analysis in the current study, the research team used the same cleaned data sets from the previous two steps and independently coded all comments from the official websites and official Facebook pages. Each sentence within each message was evaluated and classified according to the SCCT strategies. This initial coding was done independently. To create a common base of SCCT strategies for this study, an initial round of comments (20) was examined together. Once all of the sentences were coded, the research team met again to discuss any differences in the results. This continued until a final agreement was reached. The number of SCCT strategies was then counted to establish the frequency of each strategy.

Results

Qualitative content analysis–semantic analysis

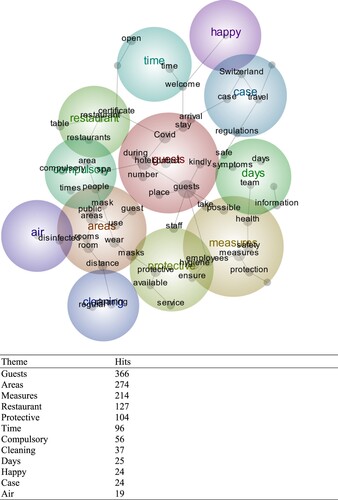

Leximancer Concept Maps are mapped according to ‘heat’, which means that hot colours (orange, red, and yellow) indicate the most prominent themes, while cold colours (green, blue, purple) represent less important ones (Leximancer, Citation2021). The size of the theme circle has no significant indication. The initial results for all comments from both the official websites and the Facebook pages can be seen in .

From the Leximancer results, the most significant of the 12 themes are ‘guests’, ‘protective measures’, and ‘areas’ in which these protective measures occur (See ). The concepts are ranked based on the frequencies of co-occurrence in the transcripts. Count represents the number of times a concept appears in the data by 2-sentence blocks, and Relevance represents the most frequent concept(s) (Smith & Humphreys, Citation2006; Sotiriadou et al., Citation2014). The map is produced in colours with concepts sharing a theme in the same colour as their cluster group circle and cluster label (Leximancer, Citation2021; Sotiriadou et al., Citation2014).

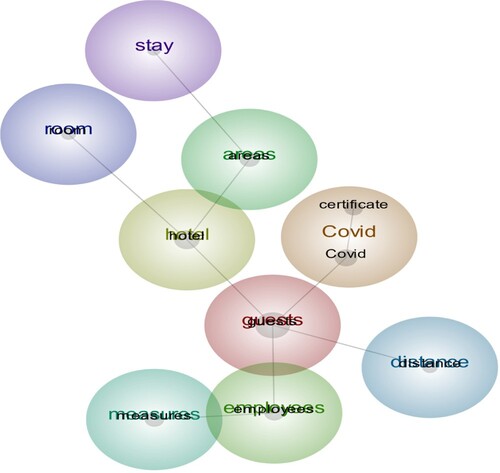

A further analysis (See ) identified the nine most relevant concepts in both Facebook and the official websites combined. The most prominent concepts were seen in ‘guests’ (179 hits), ‘hotel’ (96 hits), and ‘measures’ (93 hits), ‘Covid’ (76 hits), followed by ‘areas’ (75 hits), ‘employees’ (70 hits), ‘room’ (66 hits), ‘distance’ (61 hits), and ‘stay’ (48 hits). Of those relevant concepts, only three appeared in warm colours (guests, Covid, and hotel), suggesting they were used more frequently than other words, but not significant in these results. Only three words appeared on both outputs between the themes and concepts, i.e. ‘guests’, ‘measures’, and ‘areas’. All other words from the output appeared either as a theme or a concept, but not both. Nonetheless, ‘guests’ appeared first on both lists and all subsequent data manipulations (Facebook alone or website alone).

Sentiment analysis

A sentiment analysis of all the messages from the official hotel websites and Facebook pages was conducted using the Monkeylearn software. summarizes the findings of the sentiment analysis.

Table 2. Sentiment analysis of official hotel websites and Facebook pages.

The results show an overwhelming positive sentiment analysis for comments posted both on Facebook and the official hotel websites. Phrases such as ‘Our staff members give everything for our guests’ or ‘Fed up with home office? We have quite a pleasant alternative for you’ emphasize the positive sentiments hoteliers are trying to communicate to their guests. Examples of more positive, negative, and neutral comments can be seen in . As the hospitality and tourism industries have greatly suffered throughout the pandemic, it is not surprising that hoteliers would choose to focus on the positive return to ‘normal’. Examples of positive, negative, and neutral comments can be seen in .

SCCT strategies

The SCCT strategies used within the official Facebook and website messages were analysed. shows the results.

Table 3. SCCT strategies for official website and Facebook messages.

It is interesting to note that the usage of the SCCT strategies varied greatly between the channels. For example, the most often employed SCCT strategies for Facebook were renewal (70%), corrective action (63%), and enhancing (50%). On the other hand, corrective action was used 100% of the time on the official websites, followed by ingratiation (63%) and transferring (62%). The different SCCT strategies used by two channels may indicate hoteliers had different intentions of these channels, and consciously presented various content. Further research is needed to confirm if hoteliers have different intentions and purposes for different channels.

In a victim crisis, companies should communicate a base response of instructing and adjusting information (Coombs, Citation1995; Citation2007; Citation2017). The wide use of corrective action may indicate hoteliers’ application of providing instructing and adjusting information. demonstrates that victimization was the least used SCCT strategy on both Facebook and the official hotel websites (11% and 2% respectively), followed by scapegoating (18% and 15% respectively). The finding contradicts an earlier study using the same hotels where victimization was the most frequently employed by hoteliers (Zizka et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, it may indicate that because COVID lasted longer than a typical crisis, along with the changing government policies, hoteliers realized that they could not simply settle as victims and must actively communicate positively and constructively.

To illustrate an example of scapegoating, one hotel posted on Facebook: Due to the current protective measure, masks are compulsory. An example of transferring from an official hotel website read: ‘We strictly follow the recommendations and regulations of the Federal Council and the WHO to contain the virus’. For corrective actions, the Facebook posts and official websites ranged from one sentence: ‘Monday 31.5.2021 re-opening of restaurants’ (Facebook) and ‘Our safety and hygiene measures for the spa can be found here’ (website) to over 185 sentences detailing all of the corrective actions the hotel was taking. The latter was found on the official website where hoteliers had the liberty to write as much as they wanted to clarify exactly what they were doing. At times, this read like justification, i.e. excusing themselves for the ‘different’ experience their clients would have. However, the length offered them the opportunity to remind customers of all of the services they have at the hotel, which may have led to further reservations for these supplementary outlets.

The Facebook posts predominantly focused on the renewal strategy with phrases such as ‘A cool Corona 8 table! We are happy’ or ‘In a good mood and friendly masked, we continue to welcome you in our spacious and airy premises with guaranteed enough distance’. These examples serve as both a reminder of what the property has to offer as well as the optimistic rhetoric to the post-crisis phase (i.e. renewal).

On hotel websites, hoteliers used corrective action in all messages (100%) and ingratiation and transferring more than double of any other strategy. Many messages focused on the Swiss government or the WHO as third parties who have ‘obliged’ them to implement specific measures. These messages often combined numerous strategies into the same message: ‘We strictly comply with the advice and instructions of the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) and keep our staff and guests constantly informed of the latest developments. For the safety of our guests and employees, we have adjusted our services and implemented a wide range of safety and hygiene measures’. In this example, the hotelier has employed transferring (i.e. FOPH), scapegoating (‘we strictly comply’, i.e. we have no choice), ingratiation (i.e. ‘for the safety of our guests and employees’), and corrective actions (i.e. ‘we have adjusted our services’).

Discussion

Common themes from semantic analysis

Overlapping themes such as ‘protective’ and ‘measures’ in relation to ‘employees’, ‘hygiene’, and ‘ensuring’ were identified in the Leximancer map (See ). Hoteliers focused predominantly on the concrete actions they could take to keep the guests safe. Although ‘employees’ appeared in the orange bubble overlapping with protective and measures, they were not a significant theme on their own in the findings. By contrary, guests were in the warmest bubble along with stay, number, place, kindly, arrival, and Covid. These results suggest practical information (i.e. instructing information) that is part of a crisis communication base response. The protective measures detailed the corrective actions hoteliers had put into place. Corrective actions are a part of the greater SCCT strategies that can be utilized in times of crisis.

Of the 12 bubbles created from the comments, eight were in cold colours, thus suggesting that they were not significant themes. One of the coldest bubbles represented an emotion, i.e. happy. Hence, the hoteliers had an overwhelmingly positive sentiment in their messages but did not use the word ‘happy’ to display their emotions. Rather, they incorporated words such as ‘friendly’, ‘good mood’, ‘amazing’, ‘enjoy’, ‘dear guests’, ‘delighted’, and ‘look forward’. Further, in all posts combined, 51 exclamation points were used to show an intense feeling of joy or perhaps relief (38 in Facebook posts to 13 in website messages). For Facebook, exclamation points followed phrases such as ‘Spot the smile!’ or ‘We look forward to welcoming you back!’. For the websites, phrases such as ‘All rooms are professionally disinfected and then sealed!’ or ‘Due to the Covid-19 situation, bookings can be cancelled free of charge up to and including the day of arrival!’. From a grammatical viewpoint, these phrases would not have usually been punctuated with an exclamation mark, but, in these troubling times, hoteliers may have felt that the additional emotion was merited. Thus, hoteliers used exclamation points in the website messages to emphasize further the extraordinary measures they were taking at this time.

Sentiment analysis and SCCT strategies

The results of sentiment analysis show how the messages posted by Swiss hoteliers were categorized based on the written text (positive, negative, or neutral). For both Facebook and the websites, the vast majority of the sentiment was positive. Hoteliers attempted to foster a positive feeling in an extended and uncertain crisis. Nonetheless, while we can establish a penchant for positive messages, we do not know how the customers reacted to the messages as that is beyond the scope of the project.

The results show that hoteliers adopted different SCCT strategies on their Facebook posts versus their official websites. While the Facebook posts predominantly focused on the positive return to normal and reminded the customers of what they had missed, not all Swiss hoteliers consistently posted their corrective actions. According to the literature on social media during a crisis, many customers seek information from a company’s social media sites. Thus, the omission of the corrective actions in a channel that many guests will use was seemingly an ineffective strategic choice.

Of the 14 SCCT strategies from that Swiss hoteliers could have employed, the findings show that only seven strategies were actually employed. The missing strategies are attack, denial, excuse, justification, full apologies, mortification, and ignoring. It is crucial to point out that the 23 hotels that posted no Covid-19-related message may have employed the denial or ignoring strategies or may have been closed at the moment of this study. Nonetheless, according to Coombs (Citation2007), these hoteliers should have addressed the pandemic somehow. A message is better than no message at all.

On the websites, however, all hoteliers provided the corrective actions but often shaped them in a way to ingratiate themselves to the guests. Unlike earlier studies on the same Swiss hotel sample, this study showed less reliance on victimization and much more on a positive spirit moving forward. This could be linked to the numerous waves, the openings and closings, or the ever-changing sanitary restrictions. Hoteliers may have felt helpless earlier in the pandemic; with time, they may have become more resilient and shifted towards a positive future where their guests can enjoy their facilities again. The Swiss hoteliers in this study effectively implemented the transferring strategy as a way to justify their choices and explain the measures they were obliged to take for the safety of all.

Theoretical and managerial implications

In this study, we have analysed the Covid-19 messages deriving from Swiss 4- and 5-star hotels over a year. As seen in the literature, conducting content analysis through Leximancer, performing sentiment analysis to social media posts and website content, or applying SCCT to crisis communication messages have been used extensively in tourism research. Previous researchers have identified that tourism sentiment analysis studies focused on user-generated contents (Hao et al., Citation2021), which represents the perceived image by the consumer of the property or location. In our study, we have analysed the projected image communicated by the hoteliers to the consumers. We have found no previous study that has focused on the projected image or combines the three methods to independent hotel’s official website and Facebook messages. Although topic modelling and sentiment analysis have been used in many studies, the addition of the SCCT strategies contributes to the originality of the project. Further, while many studies have used SCCT to examine responses in crises, we have found no study that combined SCCT with topic modelling and sentiment analysis. Hence our first academic contribution is applying semantic analysis, sentiment analysis, and SCCT analysis, a triangulate approach to examine SCCT crises communication research. Our second academic contribution is to focus on the projected image of crisis communication created by hoteliers, rather than perceived image of customers.

In the present study, we began by collecting, cleaning, and coding all of the messages related to the Covid-19 pandemic mined from the hotels’ official Facebook pages and websites. We examined the frequency of themes and concepts of the words used by the hoteliers in these messages to establish patterns (See and ). In a second step, we looked at the sentiment analysis of the communicated messages. Here, we ascertained that the messages were predominantly positive (See ). Finally, we linked the comments to the SCCT strategies that were implemented to draw conclusions on the effectiveness of the crisis messages. This study was an initial step in creating a strategic crisis communication model for the tourism and hospitality industries. Nonetheless, we believe that our 3-method, holistic view of hotel messages over an extended period of the pandemic offers an original perspective on communicating during a crisis and contributes to the existing literature. Further, hoteliers could use these results to benchmark their own communication performance and identify opportunities to improve.

Based on the analysis of this study’s findings, numerous lessons can be learned. First of all, hospitality and tourism professionals need to be more proactive when communicating during a crisis (Kwok et al., Citation2021; Moller et al., Citation2018; Park et al., Citation2019). They need to meet their customers where they are; in this case, it is on social media (Schroeder et al., Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2022; Zizka et al., Citation2021). While our study confirms that the hotels did post base response messages (i.e. corrective actions), they were reporting what had been established by the Swiss authorities, i.e. they reported in a reactive manner. Further, our findings demonstrate that website messages were more rational in their approach while social media messages were more emotional. This follows the intended purpose of each channel; websites are informative and accurate, while social media emphasize the human and ‘social’ side of communication.

Secondly, this ‘fear’ of damaging their reputation by speaking about a crisis is erroneous. As seen in the literature, effective and timely communication is better than no communication at all (Barbe & Pennington-Gray, Citation2018). The hospitality and tourism sectors need to hone their social media skills when communicating during a crisis (Kwok et al., Citation2021; Park et al., Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Although the initial panic of the Covid-19 pandemic has subsided, new waves continue to emerge. The difference, however, is our ability to manage these waves. Realistically, Covid has become another ‘common cold’ that we will face each flu season. However, if it were to become an epidemic or pandemic, hoteliers would need to be prepared. Communication during crisis time needs to be timely, and consider audience, sources, and channels (Xie et al., Citation2021). There is a clear need for a strategic communication plan to guide them when communicating with their stakeholders.

During the crisis situation, the firm’s priority is to protect guests rather than reputational concerns (Coombs & Holladay, Citation2002). The positive sentiment, the extensive use of exclamation points, the wide adoption of ingratiation and enhancing all remind us the humanness in times of crisis (Camilleri, Citation2020; Zizka et al., Citation2021). After the COVID-19 pandemic, the ubiquitous automation, robots, and AI make humanness and humanity even more precious. Applying SCCT protect organization’s reputation during a crisis will work even more effectively with compassion and humanity.

Limitations and further research

This study was limited to Swiss 4- and 5-star hotels. Future studies could expand this research to other hotel categories and hotels in other countries. Another limitation was the use of hotels only. A further study could expand the research to the greater hospitality and tourism sectors. A third limitation was the use of the official Facebook pages and websites only. Many hotels also hold other social media accounts, and these could be examined in a future study. Finally, by analysing the comments from the hotels alone, only one-way communication was investigated. Additional studies could examine the two-way communication process between hoteliers and clients, hoteliers and employees, or hoteliers and supplies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Tagliche Praxis, 53(1), 51–58.

- Alaei, A. R., Becken, S., & Stantic, B. (2019). Sentiment analysis in tourism: Capitalizing on big data. Journal of Travel Research, 58(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517747752

- Austin, L., Fisher Liu, B., & Jin, Y. (2012). How audiences seek out crisis information: Exploring the social-mediated crisis communication model. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 40(2), 188–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2012.654498

- Avraham, E. (2020). From 9/11 through Katrina to COVID-19: Crisis recovery campaigns for American destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(20), 2875–2889. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1849052

- Azer, J., Blasco-Arcas, L., & Harrigan, P. (2021). #COVID-19: Forms and drivers of social media users’ engagement behavior toward a global crisis. Journal of Business Research, 135, 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.06.030

- Barbe, D., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2018). Using situational crisis communication theory to understand Orlando hotels: Twitter response to three crises in the summer of 2016. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 1(3), 258–275. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-02-2018-0009

- Camilleri, M. A. (2020). Strategic dialogic communication through digital media during COVID-19 crisis. In M. A. Camilleri (Ed.), Strategic corporate communication in the digital age (pp. 1–25). Emerald.

- Cheng, M., & Edwards, D. (2019). A comparative automated content analysis approach on the review of the sharing economy discourse in tourism and hospitality. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1361908

- Cheng, Y. (2018). How social media is changing crisis communication strategies: Evidence from the updated literature. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 26(1), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12130

- Claeys, A.-S., Cauberghe, V., & Vyncke, P. (2010). Restoring reputations in times of crisis: An experimental study of the situational crisis communication theory and the moderating effects of the locus of control. Public Relations Review, 36(3), 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.05.004

- Contreras, D., Wilkinson, S., Alterman, E., & Hervás, J. (2022). Accuracy of a pre-trained sentiment analysis (SA) classification model on tweets related to emergency response and early recovery assessment: The case of 2019 Albanian earthquake. Natural Hazards, 113(1), 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-022-05307-w

- Contreras, D., Wilkinson, S., Balan, N., & James, P. (2021). Assessing post-disaster recovery using sentiment analysis: The case of L’Aquila, Italy. Earthquake Spectra, 38(1), 81–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/87552930211036486

- Coombs, W. T. (1995). Choosing the right words: The development of guidelines for the selection of the ‘appropriate’ crisis response strategies. Management Communication Quarterly, 8(4), 447–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318995008004003

- Coombs, W. T. (2007). Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(3), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550049

- Coombs, W. T. (2017). Revisiting situational crisis communication theory. In A. Lucinda & J. Yan (Eds.), Social media and crisis communication (pp. 41–58). Routledge.

- Coombs, W. T., & Holladay, S. J. (2002). Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 165–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/089331802237233

- Dulaney, E., & Gunn, R. (2017). Situational crisis communication theory and the use of apologies in five high-profile food-poisoning incidents. Journal of the Indiana Academy of the Social Sciences, 20(1), 13–33. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/jiass/vol20/iss1/5

- Flores-Ruiz, D., Elizondo-Salto, A., & Barroso-Gonzalez, M. D. L. O. (2021). Using social media in tourist sentiment analysis: A case study of Andalusia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 13(7), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073836

- Fu, Y., Hao, J. X., Li, X., & Hsu, C. H. (2019). Predictive accuracy of sentiment analytics for tourism: A metalearning perspective on Chinese travel news. Journal of Travel Research, 58(4), 666–679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518772361

- Gonzalez, I. O., Camarero, C., & San Jose Cabezudo, R. (2021). SOS to my followers! The role of marketing communications in reinforcing online travel community value during times of crisis. Tourism Management Perspectives, 39, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100843

- Hao, J.-X., Fu, Y., Hsu, C., Li, X., & Chen, N. (2020). Introducing news media sentiment analytics to residents’ attitudes research. Journal of Travel Research, 59(8), 1353–1369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519884657

- Hao, J. X., Wang, R., Law, R., & Yu, Y. (2021). How do mainland Chinese tourists perceive Hong Kong in turbulence? A deep learning approach to sentiment analytics. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(4), 478–490. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2419

- Jiminez-Barreto, J., Loureiro, S., Braun, E., Sthapit, E., & Zenker, S. (2021). Use numbers not words! Communicating hotels’ cleaning programs for COVID-19 from the brand perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102872

- Jingyi, L., Furuoka, F., Lim, B., & Hanim Pazim, K. (2020). Risk perception and domestic travel intention during the COVID-19 pandemic: A conceptual paper. Journal for Sustainable Tourism Development, 9(1), 7–19. https://doi.org/10.51200/bimpeagajtsd.v9i1.3175

- Jong, W. (2020). Evaluating crisis communication. A 30-item checklist for assessing performance during COVID-19 and other pandemics. Journal of Health Communication, 25(12), 962–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1871791

- Kazeminia, A., Del Chiappa, G., & Jafari, J. (2015). Seniors’ travel constraints and their coping strategies. Journal of Travel Research, 54(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287513506290

- Ki, E.-J., & Nekmat, E. (2014). Situational crisis communication and interactivity: Usage and effectiveness of Facebook for crisis management by fortune 500 companies. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 140–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.02.039

- Kim, H., Li, J., & So, K. K. F. (2021). The hotel industry’s responses to COVID-19: Insight from hybrid thematic analysis and experimental research. Travel and Tourism Association: Advancing Tourism Research Globally, 59, 1–17. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/ttra/2021/research_papers/59?utm_source = scholarworks.umass.edu%2Fttra%2F2021%2Fresearch_papers%2F59&utm_medium = PDF&utm_campaign = PDFCoverPages

- Kim, S., & Liu, B. F. (2012). Are all crises opportunities? A comparison of how corporate and government organizations responded to the 2009 flu pandemic. Journal of Public Relations Research, 24(1), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/1062726X.2012.626136

- Kwok, L., Lee, J., & Han, S. H. (2021). Crisis communication on social media: What types of COVID-19 messages get the attention? Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 63(4), 528–543. https://doi.org/10.1177/19389655211028143

- Leximancer. (2021). Leximancer user guide. Leximancer Pty Ltd, release 4.5. https://doc.leximancer.com/doc/LeximancerManual.pdf

- Li, J., Nguyen, T. H. H., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2020). Coronavirus impacts on post-pandemic planned travel behaviours. Annals of Tourism Research, 86, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102964

- Liu, W., Lai, C.-H., & Xu, W. (2018). Tweeting about emergency: A semantic network analysis of government organizations’ social media messaging during Hurricane Harvey. Public Relations Review, 69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.10.009

- Liu, Y., Shi, H., Li, Y., & Amin, A. (2021). Factors influencing Chinese residents' post-pandemic outbound travel intentions: An extended theory of planned behavior model based on the perception of COVID-19. Tourism Review, 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-09-2020-0458

- Liu-Lastres, B., Kim, H., & Ying, T. (2020). Learning from past crises: Evaluating hotels’ online crisis responses to health crises. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 20(3), 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358419857779

- Moller, C., Wang, J., & Nguyen, H. T. (2018). #Strongerhanwinston: Tourism and crisis communication through Facebook following tropical cyclones in Fiji. Tourism Management, 69, 272–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.05.014

- Natural language processing (NLP): What is it and how does it work? (2022). https://monkeylearn.com/sentiment-analysis/

- Obembe, D., Kolade, O., Obembe, F., Owoseni, A., & Mafimisebi, O. (2021). COVID-19 and the tourism industry: An early stage sentiment analysis of the impact of social media and stakeholder communication. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 1(2), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2021.100040

- Ou, J., & Wong, I. A. (2021). Strategic crisis response through changing message frames: A case of airline corporations. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(20), 2890–2904. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1849051

- Park, D., Kim, W. G., & Choi, S. (2019). Application of social media analytics in tourism crisis communication. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(15), 1810–1824. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2018.1504900

- Pearce, P. L., & Wu, M. Y. (2016). Tourists’ evaluation of a romantic themed attraction: Expressive and instrumental issues. Journal of Travel Research, 55(2), 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514538838

- Phi, G. T. (2020). Framing overtourism: A critical news media analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(17), 2093–2097. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1618249

- Roth-Cohen, O., & Lahav, T. (2021). Cruising to nowhere: COVID-19 crisis discourse in cruise tourism Facebook groups. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(9), 1509–1525. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1940106

- Salem, I. E., Elkhwesky, Z., & Ramkissoon, H. (2021). A content analysis for governments’ and hotels’ response to COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 22, 42–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584211002614

- Scheiwiller, S., & Zizka, L. (2021). Strategic responses by European airlines to the COVID-19 pandemic: A soft landing or a turbulent ride? Journal of Air Transport Management, 95, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2021.102103

- Schroeder, A., & Pennington-Gray, L. (2015). The role of social media international tourist’s decision making. Journal of Travel Research, 54(5), 584–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728754528284

- Schroeder, A., Pennington-Gray, L., Donohoe, H., & Kiousis, S. (2013). Using social media in times of crisis. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 30(1–2), 126–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2013.751271

- Smith, A. E., & Humphreys, M. S. (2006). Evaluation of unsupervised semantic mapping of natural language with Leximancer concept mapping. Behavior Research Methods, 38(2), 262–279. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192778

- Sotiriadou, P., Brouwers, J., & Le, T.-A. (2014). Choosing a qualitative data analysis tool: A comparison of NVivo and Leximancer. Annals of Leisure Research, 17(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2014.902292

- Stewart, M. C., & Young, C. (2018). Revisiting STEMII: Social media crisis communication during Hurricane Matthew. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communications Research, 1(2), 279–302. https://doi.org/10.30658/jicrcr.1.2.5

- Swiss tourism numbers crash as jobless figures rise. (2020, May 7). https://www.swissinfo.ch/eng/covid-economy_swiss-tourism-numbers-crash-as-jobless-figures-rise/45743354

- Switzerland tourist arrivals 1996–2020 data. (n.d.). https://tradingeconomics.com/switzerland/tourist-arrivals

- Trinh, T. T., & Ryan, C. (2017). Visitors to heritage sites: Motives and involvement – a model and textual analysis. Journal of Travel Research, 56(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515626305

- Tseng, C., Wu, B., Morrison, A. M., Zhang, J., & Chen, Y.-C. (2014). Travel blogs on China as a destination image formation agent: A qualitative analysis using Leximancer. Tourism Management, 46, 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.07.012

- Ulmer, R. R., & Sellnow, T. L. (2002). Crisis management and the discourse of renewal: Understanding the potential for positive outcomes of crisis. Public Relations Review, 28(4), 361–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-8111(02)00165-0

- Veil, S. R., Buehner, T., & Palenchar, M. J. (2011). A work-in-progress literature review: Incorporating social media in risk and crisis communication. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 19(2), 110–122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5973.2011.00639.x

- Villace-Molinero, T., Fernandez-Munoz, J. J., & Orea-Giner, A. (2021). Understanding the new post-COVID-19 risk scenario: Outlooks and challenges for a new era of tourism. Tourism Management, 86, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104324

- Wang, Z., Bai, G., Chowdhury, S., Xu, Q., & Seow, Z. L. (2017). Twilnsight: Discovering topics and sentiments from social media datasets. AIRV. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1705.08094

- Wong, I. A., Ou, J., & Wilson, A. (2021). Evolution of hoteliers’ organizational crisis communication in the time of mega disruption. Tourism Management, 84, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104257

- Xie, C., Zhang, J., Morrison, A. M., & Coca-Stefaniak, J. A. (2021). The effects of risk message frames on post-pandemic travel intentions: The moderation of empathy and perceived waiting time. Current Issues in Tourism, 24(23), 3387–3406. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.188102

- Ye, S., Lee, J. A., Sneddon, J. N., & Soutar, G. N. (2019). Personifying destinations: A personal values approach. Journal of Travel Research, 59(7), 1168–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519878508

- Yeh, S.-S. (2021). Tourism recovery strategy against COVID-19 pandemic. Tourism Recreation Research, 46(2), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1805933

- Zhang, J., Xie, C., Chen, Y., Dai, Y.-D., & Wang, Y.-J. (2022). The matching effect of destinations’ crisis communication. Journal of Travel Research, 62(3), 491–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211067548

- Zizka, L., Chen, M.-M., Zhang, E., & Favre, A. (2021). Hear no virus, see no virus, speak no virus: Swiss hotels’ online communication regarding coronavirus. In W. Wörndl, C. Koo, & J. L. Stienmetz (Eds.), Information and communication technologies in tourism 2021. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65785-7_43