ABSTRACT

In this conceptual paper, through the introduction of Sen’s capability approach we seek to make a significant contribution to accessible tourism research. The capability approach offers a flexible yet sophisticated theoretical framework to evaluate individuals’ achieved wellbeing and wellbeing opportunities. Drawing on the concepts of functionings and capabilities we show the conceptual leaps that can be made when prominence is given to the diversity and agency of persons with disabilities in translating the opportunity to travel (capability) to the act of travelling (functioning). The capability approach can help build a more complete understanding of what either enables or hampers travel for persons with disabilities and we identify three relevant areas for accessible tourism research – non-market resources and conversion factors, individuals’ agency and choices, and policies and interdisciplinary work. We see persons with disabilities as active in exercising their choices and agency and highlight how the capability approach can enable researchers to see and undo existing dominant ableist discourse through more interdisciplinary inquiries. The capability approach helps accessible tourism scholars broaden their horizons and develop more comprehensive understanding of how tourism can help a person to lead a life they value regardless of their disability.

Introduction

The case for making tourism and leisure activities accessible for persons with disabilities (PwD) has received increasing research attention from both economic and social rights-based perspectives. In one sense, PwD are seen as an underdeveloped and undervalued travel market segment that offers the potential for economic gains for businesses and destinations willing to tap into it (Darcy et al., Citation2010; Domínguez et al., Citation2015; Garda, Citation2022). In another sense, much attention has been given to the travel motivations, constraints, and experiences of PwD and how these impact on their wellbeing through tourism (Darcy & Dickson, Citation2009; Moura et al., Citation2023; Załuska et al., Citation2022). Both approaches have helped to move the debate forward and to make accessible tourism a key concern in terms of academic research and policy. While research on accessible tourism continues to grow, there is room for deeper conceptual engagement that can integrate what might be seen as a disparate, limited, and fragmented field. Consolidatory work has been done in the recent past taking stock of the accessible tourism research field in terms of bibliometric studies that aggregate extant knowledge (Qiao et al., Citation2022; Rubio-Escuderos et al., Citation2021b; Suárez-Henríquez et al., Citation2022). In addition, some studies have focused on conceptual explorations in the field (Bellucci et al., Citation2023; Bhogal-Nair et al., Citation2023; Gillovic & McIntosh, Citation2020; Hansen et al., Citation2021). Yet, there remains a gap for wider conceptual evolutions and developments across the social sciences.

In this paper we seek to make a significant contribution by rethinking some of the key issues in the accessible tourism literature in the context of Sen’s capability approach. Our intention is to highlight the relevance of the capability approach, in particular, the concepts of functionings and capabilities, to accessible tourism, and demonstrate how this approach can enrich our conceptualization of accessible tourism and contribute to the theoretical advancement of the field. We show how integrating the capability approach into accessible tourism research allows us to see and undo the dominant ableist discourse. This is accomplished by promoting new accessible tourism research inquiries that are more participatory and inclusive. Our analysis also identifies the ways in which the capability approach gives prominence to PwD’s choices and agency in translating the opportunity to travel (capability) to the act of travelling (functioning). Thus, a positive agency-based starting point is afforded to accessible tourism research through the capability approach in which PwD are seen as active in exercising their choices and agency based on their diverse motivations, interests, and preferences. We structure this conceptual paper as follows: after this introduction, an overview of current debates in accessible tourism is provided before outlining the key aspects of the capability approach. We then discuss the ways the capability approach provides new insights into rethinking accessible tourism research before outlining our arguments and future research agenda in the conclusion section.

Current debates in accessible tourism

At its heart, accessible tourism springs from the concerns and access needs of persons with disabilities (PwD). The World Health Organization (WHO) in its latest report estimates that globally 1.3 billion people experience significant disability, which represents 16% of the world’s population. PwD are faced with health inequities due to factors that are structural (stigma, ableism, and discrimination) and socially determined (poverty, exclusion, and gaps in social support systems) (WHO, Citation2023). To date, two main conceptualizations dominate in the accessible tourism literature – the medical model and the social model of disability. The medical model focuses on the impairment of individual bodies and advocates for policies towards medical treatment and physical rehabilitation for individuals to adapt to their disability and environment (Burnett & Baker, Citation2001). In contrast, the social model, while not denying the medical basis of impairments, considers disability as socially constructed. This social construction of disability refers to the ways in which society is organized that make it difficult for those with impairments to function fully. The social model therefore focuses on the structural and social factors that render impaired individuals into ‘disabled’ individuals through economic, physical, political, and social exclusions and inaccessibility (Gillovic et al., Citation2018; Zajadacz, Citation2015). While earlier research was largely underpinned by a medical model of disability (Burnett & Baker, Citation2001; Qiao et al., Citation2022), more recent work has been increasingly focused on the social model (Benjamin et al., Citation2021; Buhalis & Darcy, Citation2011; Connell & Page, Citation2019; Eichhorn et al., Citation2008).

Accessible tourism, as an umbrella concept, signifies a purposeful move from the sole focus on disability found in earlier studies and indicates the maturing of this field of research (Gillovic et al., Citation2018). Previous research on the leisure and tourism experiences of PwD was often related to terms such as ‘social tourism’, ‘disability tourism’, ‘barrier-free tourism’, ‘inclusive tourism’ and ‘tourism for all’ (Cloquet et al., Citation2018; Daruwalla & Darcy, Citation2005). Gillovic et al. (Citation2018) argue that the language of and definitional terms of accessible tourism are often used loosely and implicitly assumed as self-explanatory. Darcy and Buhalis (Citation2011) address this concern and offer a clear definitional conceptualization of accessible tourism:

Accessible tourism is a form of tourism that involves collaborative processes between stakeholders that enables people with access requirements, including mobility, vision, hearing and cognitive dimensions of access, to function independently and with equity and dignity through the delivery of universally designed tourism products, services and environments. This definition adopts a whole of life approach where people through their lifespan benefit from accessible tourism provision. These include people with permanent and temporary disabilities, seniors, obese, families with young children and those working in safer and more socially sustainably designed environments. (Adapted from Darcy & Dickson, Citation2009, p. 34) in (Darcy & Buhalis, Citation2011, pp. 10–11)

Recently there has been increased focus on conceptual developments in accessible tourism research (e.g. Duignan et al., Citation2023; Jensen et al., Citation2023; Rubio-Escuderos et al., Citation2021b; Suárez-Henríquez et al., Citation2022). More scholars now consider accessible tourism in relation to other concepts within tourism and in the wider social science disciplines. For instance, studies linking accessible tourism with social tourism highlight how social tourism policies facilitate accessible tourism by encouraging the participation and inclusion of PwD with economic and other disadvantages (Diekmann et al., Citation2018; Minnaert et al., Citation2011). Building on the work of Scheyvens and Biddulph (Citation2018), Gillovic and McIntosh (Citation2020) call for re-appraising accessible tourism through the lens of inclusive tourism development and pursuing broader transformations inside and outside of the tourism industry. They argue that such an approach offers conceptual and empirical benefits to accessible tourism research ‘because it is fundamentally about the inclusion of people with disabilities in tourism, and in society’ (p. 10). However, Darcy et al. (Citation2020, p. 141) caution that while inclusive and social tourism offer complementary insights, there is a need to have an exclusive focus on ‘accessible tourism for those with access requirements, which are not shared with other marginalised identities’. Hansen et al. (Citation2021) have put forward an interdisciplinary argument for conceptual connection between accessible tourism and occupational therapy. They identify synergies to be realized between the two fields in their shared concerns, such as, deprivation, social exclusion, barriers to participation and bolstering quality of life of everyone. Furthermore, Tomej and Duedahl (Citation2023) offer a relational interdependence perspective on disability and accessible tourism, highlighting how PwD develop their agency to perform travel actions in the context of the societal power imbalances. Others (Farkas et al., Citation2022; Happ & Bolla, Citation2022) also attempt to link disability and accessibility in tourism with the concept of sustainability.

We build on the emerging conceptual development in this area by examining accessible tourism research in the context of Sen’s capability approach – in particular the concepts of functionings and capabilities. The capability approach aligns with the social model of disability and its emphasis on human diversity can help develop a more holistic and nuanced understanding of what either enables or hampers PwD’s opportunities to travel.

The capability approach and disability

The capability approach was pioneered by Amartya Sen, a renowned international development economist. It is a well-established conceptual framework in development and social justice studies and has been widely applied in many social science disciplines including education, public health, sustainability and environmental policies, disabilities, and education (Robeyns, Citation2017). Here, we present insights from Sen’s capability approach at the general level vis-à-vis how it can push accessible tourism research forward.

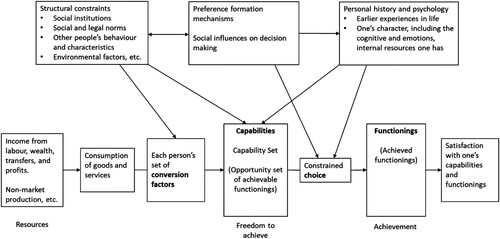

Sen developed the capability approach as an alternative paradigm to evaluate human wellbeing and development. Whereas traditional approaches over-emphasized opulence (e.g. based on income or GDP per capita) or utility (e.g. based on mental states of happiness) (Alkire, Citation2015; Clark, Citation2005a; Robeyns, Citation2017), Sen ‘gives a central role to the evaluation of a person’s achievements and freedoms in terms of his or her actual ability to do the different things a person has reason to value doing or being’ (Citation2009, p. 16). illustrates the core concepts of Sen’s capability approach, namely, functionings and capabilities, conversion factors, and choice (agency).

Figure 1. The core concepts of the capability approach (Adapted from Robeyns, Citation2005, p. 98, Citation2017, p. 83).

The capability approach highlights multi-dimensional wellbeing and human diversity. Human life consists of many beings and doings, in other words, functionings. Some functionings might be considered as universal (e.g. being nourished, being sheltered) whereas others are context dependent, based on different social circumstances, values, and experiences (Robeyns, Citation2017; Stiglitz et al., Citation2009). These achieved functionings constitute a person’s wellbeing, and the capabilities to achieve functionings constitute ‘the person’s freedom – the real opportunities – to have well-being’ (Sen, Citation1992, p. 40), simply put, ‘what people are able to be and to do’ (Robeyns, Citation2017, p. 38). Robeyns uses travelling as an example to explain the two concepts:

Capabilities are a person’s real freedoms or opportunities to achieve functionings. Thus, while travelling is a functioning, the real opportunity to travel is the corresponding capability. A person who does not travel may or may not be free and able to travel; the notion of capability seeks to capture precisely the fact of whether the person could travel if she wanted to. The distinction between functionings and capabilities is between the realized and the effectively possible, in other words, between achievements, on the one hand, and freedoms or opportunities from which one can choose, on the other. (Citation2017, p. 39)

As presented in , Sen also highlights a person’s agency and choice ‘to determine what we want, what we value and ultimately what we decide to choose’ (Citation2009, p. 232). The bicycle example can illustrate human diversity in choices and agency as people can use the same resource (i.e. bicycle) for different purposes (e.g. cycling to work or social gatherings, cycling as exercise or leisure activity) and achieve various functionings they value. In contrast, for someone who must cycle a long distance every day for work without alternative transport choices, cycling could be harmful for their wellbeing (Clark, Citation2005a). As functionings and capabilities are value neutral in themselves, the evaluation of personal wellbeing and social arrangements should be in line with the extent of opportunities people have both to achieve functionings they value and to weaken the functionings with a negative value (Robeyns, Citation2017).

This multi-dimensional and context-dependent nature of the capability approach has led to criticisms. Critics argue that there is lack of specificity regarding how to decide what capabilities matter and how to measure and assess those dimensions, which makes operationalization of the capability approach challenging (Chiappero-Martinetti et al., Citation2015; Hick, Citation2012). Nussbaum (Citation2003), for instance, criticizes Sen for not providing a specific and well-defined list of capabilities for universal applications. However, Sen refuses to endorse a ‘fixed and final list of capabilities usable for every purpose’ (Sen, Citation2004, p. 77). Sen acknowledges that each specific theory or application based on the capability approach will require a selection of valuable capabilities that fits their purpose and context but emphasizes that in such cases, the selection of capabilities should involve democratic processes and social choice procedures rather than being guided by theory alone (Sen, Citation2004, Citation2009). We see the complexity and ambiguities of the capability approach as potential strengths (Alkire, Citation2002; Chiappero-Martinetti et al., Citation2015; Clark, Citation2005b; Winter & Kim, Citation2021) as they allow open and flexible research that reflects individual diversity and multi-dimensional wellbeing and encourages innovative methodologies and tools. This is particularly relevant for tourism and disability research given the complex and nuanced notion of disabilities.

Others also critique the capability approach as too individualistic and as not paying sufficient attention to social structures and the collective aspects of living (Jackson, Citation2005; Stewart, Citation2005). However as shown in , the capability approach considers social structures, institutions, and norms, firstly through the concept of conversion factors which influence the conversion of resources into capabilities and secondly by factoring in the social influences on choices people make when realizing capabilities to achieved functionings (Robeyns, Citation2017). Drèze and Sen (Citation2002, p. 6) argue that ‘the options that a person has depend greatly on relations with others and on what the state and other institutions do. We shall be particularly concerned with those opportunities that are strongly influenced by social circumstances and public policy’. In fact, the predominant applications of the capability approach have been in the evaluation of ‘(1) the assessment of individual levels of achieved wellbeing and wellbeing freedom; (2) the evaluation and assessment of social arrangements or institutions; and (3) the design of policies and other forms of social change in society’ (Robeyns, Citation2017, p. 24).

In disability-related disciplines, the capability approach has received attention as a comprehensive conceptual framework for disability that can complement the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) model (e.g. Mitra, Citation2006; Sylvester, Citation2011; Trani et al., Citation2011; Wise, Citation2018). The ICF attempts to integrate the medical and social models of disability and to address the interaction between disability and functioning in the environment people live in (WHO, Citation2001). However, it fails to adequately reflect personal and socio-economic factors that create interpersonal variation (Masala & Petretto, Citation2008; Mitra, Citation2006). Also, despite its emphasis on performance (i.e. what people do in their current environment), the ICF neither considers opportunities to carry out performance nor recognizes PwD’s agency and choice (Trani et al., Citation2011). These shortcomings can be addressed, even lessened through the capability approach.

There are several key strengths in using the capability approach. Firstly, the capability approach considers the factors leading to different opportunities. These include, resources, personal characteristics, and the environment, including the economic burden of the person with an impairment (Mitra, Citation2006). Secondly, the capability approach’s multi-dimensional stance of wellbeing can assist in examining many aspects of PwD’s lived experiences, which can inform policies and social change (Robeyns, Citation2020). Thirdly, its focus on real opportunities and personal values helps the capability approach address the importance of individuals’ agency to pursue the life they value and assist public policies to concentrate more on removal of barriers and creation of opportunities (Trani et al., Citation2011). In short, the capability approach can provide a comprehensive and holistic framework which ‘encompasses all dimensions of individual well-being and does not limit its view to the impairment or to the disabling condition’ (Trani et al., Citation2011, p. 146).

Recently, emerging research in accessible tourism has begun engaging with the capability approach, albeit in specific contexts. Zahari et al. (Citation2023), for instance, broadly situate their study in the capability approach and argue for PwD’s rights to engage in social activities through heritage tourism. Bellucci et al. (Citation2023) also use the capability approach to identify important individual and social wellbeing dimensions in a quantitative analysis of the social impacts of PwD’s inclusion in jobs in the hospitality sector. Our current paper is therefore a well-timed contribution to the field as we draw out a comprehensive usefulness of the capability approach and discuss the ways it can potentially further advance conceptual and empirical development in the accessible tourism field.

The capability approach and accessible tourism: resources, conversion factors and capabilities

The capability approach directs us to question ‘whether a person is being put in the conditions in which she can pursue her ultimate ends’ rather than fixating on a single, particular means (Robeyns, Citation2017, p. 49). As shown in , to achieve the functioning of travelling, PwD need various resources, such as, money, time, and goods and services from market and non-market production. These resources and PwD’s conversion factors determine whether they have a genuine opportunity to travel. The resources and conversion factors are frequently viewed in accessible tourism literature through the lens of the constraints that PwD face. Intrapersonal constraints are associated with an individual’s physical and psychological abilities whereas interpersonal constraints arise from a person’s social interaction or relationships with travel companion, service providers, locals, and tourists among others. Structural constraints include financial issues, architectural, ecological and transportation barriers, and regulation barriers (Gassiot et al., Citation2018; Lee et al., Citation2012). Here the capability approach encourages us to pay more consideration to non-market resources and conversion factors, and social institutions and norms, and build a more comprehensive understanding of what enables or hampers PwD’s opportunities to travel.

Having the real freedom or opportunity to travel is a personal capability. However, to realize this capability and achieve the corresponding functionings they desire, many PwD depend on others (Robeyns, Citation2017; Sen, Citation2002), such as, families and friends and disability organizations. In this sense, travelling is what Sen calls ‘socially dependent individual capability’ (Citation2002, p. 85). PwD’s family members are often their caregivers and travel companions. Family members influence PwD’s travel motivation, decision-making and experiences (Domínguez et al., Citation2013; Eichhorn et al., Citation2013; Tao et al., Citation2019; Yau et al., Citation2004) and their role is even more critical in travel decision-making for persons with cognitive disabilities. To understand what opportunities are truly available to PwD, it is necessary to examine the interdependence between PwD’s and their families’ opportunities and choices (Robeyns, Citation2017).

The capability approach thus urges us to consider PwD’s capabilities and functionings in conjunction with those of their families and caregivers. When caregiving family members have to give up their own opportunities for a family member with disability or vice versa, the value of their experiences, such as a holiday trip, is questionable for both. For example, Lehto et al. (Citation2018) show that while holiday trips contribute to PwD’s self-discovery, social bonding, and intellectual development, they bring emotionally intensive and mixed experiences for both PwD and their families/caregivers. PwD and their families often make trade-offs between the needs of the PwD and the whole family when going on holidays. Mactavish et al. (Citation2007) and Nyman et al. (Citation2018) found a similar result when families have to compromise destination choices and activities, include support workers in family trips, deal with intensive planning, and even give up the time as a whole family by having separate trips or leaving their children with disability at home. The sacrifice or compromise PwD’s families and caregivers make should not be taken for granted as this can negatively affect their own functioning and capabilities. The concern for caregivers/family members is important as they risk social exclusion from tourism due to their commitments (McCabe, Citation2009) or may require respite support (Hunter-Jones et al., Citation2023; Mactavish et al., Citation2007).

The capability approach also draws our attention to evaluating the interplay between poverty and disability, which is often ignored in accessible tourism literature. Many PwD are socio-economically disadvantaged and marginalized, and households with a person with disability are more likely to experience poverty compared to those without. Yet, in much of the existing literature, accessible tourism is frequently portrayed as a profitable market frontier for businesses and destinations to tap into (Darcy et al., Citation2010; Domínguez et al., Citation2015; Garda, Citation2022; Gillovic & McIntosh, Citation2015; Visit Britain, Citationn.d.). This ignores the financial difficulties faced by many PwD households. In a recent report, Evans and Collard (Citation2022) notes that 29% of PwD households are in serious financial difficulty, compared to 13% of households without disability. The cost-of-living crisis following Covid-19 disproportionately affect PwD households with 31% of them (vs 12%) reporting that the rising costs affect the number of meals they eat and 43% (vs 25%) reporting the quality of food they consume has declined. The report also shows that 35% (vs 17%) of PwD households do not spend on leisure or entertainment. Consequently, improving accessibility within the tourism industry may increase opportunities to travel for PwD who can afford it, but it does not make tourism more accessible for economically disadvantaged PwD.

In this context, the role of disability organizations, including both organizations of and organizations for PwD becomes crucial. Disability organizations inspire PwD to travel, offer expert travel advice, disseminate knowledge, provide transportation, accommodation, and tours, as well as campaigning for PwD’s participation in tourism (Blichfeldt & Nicolaisen, Citation2011; Hunter-Jones, Citation2011) and society more generally. Some charitable organizations also offer respite care or respite holidays for PwD and their families/caregivers. Such support from disability organizations can be invaluable, especially when PwD and their families/caregivers have insufficient financial resources or support from the public sector, and when the tourism industry cannot provide accessible products that meet their needs. However, the role and influence of these organizations in social tourism provision, including accessible tourism, has been neglected by scholars and requires more attention (Blichfeldt & Nicolaisen, Citation2011; Carneiro et al., Citation2022; Hunter-Jones, Citation2011; Shaw et al., Citation2020) as non-market resources and/or conversion factors that influence PwD’s capabilities.

The capability approach offers a more holistic and comprehensive framework for evaluation of the real opportunities that PwD have by paying attention to various resources and conversion factors available to them. It can help create synergy between accessible tourism and social tourism discourses and assist to ‘better understand the socioeconomic determinants of impairments and disabilities and to promote prevention as an essential element of policies jointly addressing poverty and disability’ (Mitra, Citation2006, p. 245). It can help accessible tourism scholars move beyond a myopic focus on the tourism industry to a broader social enquiry into social inclusion.

The capability approach and accessible tourism: agency, capabilities and functionings

Ultimately, the capability approach addresses ‘what it means to live well’ (Wise, Citation2018, p. 254) and the answer to this question will vary from one person to another. Agency therefore is a key element of the capability approach. Sen (Citation1999, p. 19) defines an agent as ‘someone who acts and brings about change, and whose achievements can be judged in terms of her own values and objectives, whether or not we assess them in terms of some external criteria as well’. Referring to Stones’ (Citation2005) conceptualization of active agency, Hvinden and Halvorsen (Citation2018, p. 871) raise an important question.

These aspects of active agency include their internal dialogues, critical awareness of possibilities for change in the world around them, planning, decision-making, choice, discussion and interaction with others. Active agency refers also to the practical steps – action – that a person takes to achieve some particular aim or outcome, single-handedly or together with others. We assume that active agency is responsive to, but not simply determined by or dependent on, contextual, social and environmental processes, whether directly experienced or mediated in one way or other. Our interest is not only in how persons’ active agency influence the conversion between a capability set and achieved functionings. A key question is whether – and to what extent – achieved functionings enter into (or serve as basis for) their active agency in the next instance, with the potential result of changing the capability set, the capability inputs, or even the conversion factors, whether locally or more broadly, for better or worse.

The capability approach gives prominence to PwD’s choice and active agency. PwD exercise their choices and agency arising from diverse motivations, interests, and preferences. They value making their own decisions and having autonomy (Rubio-Escuderos et al., Citation2021a). For example, Ho and Peng (Citation2017) show how hearing-impaired backpackers, who previously had disappointing group tour experiences, enjoy travelling with their hearing-impaired friends and pursue more authentic local experience through backpacking. Merrick et al. (Citation2021) show how disabled paddlers with more experience found the accessible paddling programme unsatisfying as the heavy focus on health and safety could not give them the level of risk or challenge that they desire. Michopoulou and Buhalis (Citation2013) highlight the need for more flexible and personalized information system design, which can enable PwD to choose tourism products and services that best serve both their access needs and preferences. By stressing personal diversity and agency, the capability approach encourages scholars to define a person by their values, beliefs and preferences within a given social environment (Trani et al., Citation2011), not just by their disability.

However, to become travel active, PwD first need courage to overcome both physical and external barriers and intrinsic barriers such as self-doubt (Yau et al., Citation2004). Despite the numerous studies focusing on the constraints that PwD face, relatively little attention has been paid to strategies that PwD employ to negotiate and overcome these constraints (Devile et al., Citation2023). This highlights the need for more research not only into the kind of economic, social, and cultural capital but also the psychological capital people need to engage in holidaying (Morgan et al., Citation2015). The capability approach stresses ‘the importance of empowering people to help themselves, and of focusing on individuals as the actors of their own development’ (Stiglitz et al., Citation2009, p. 151). This viewpoint is important to help more PwD participate in traveling and enjoy the well-studied benefits. The capability approach enables to study PwD’s personal characteristics and internal resources and how they exercise their agency and choice in realizing travel opportunities in a more sophisticated and nuanced way.

Equally, it should be noted that the importance people give to travelling differs substantially depending on priorities in their lives (Randle et al., Citation2019). Therefore, travelling should be considered in relation to other capabilities and functionings of PwD’s lives and the wellbeing analysis should address ‘not only which opportunities are open to us individually … but rather which combinations or sets of potential functionings that are open to us’ (Robeyns, Citation2017, p. 52). Travelling may be a valuable functioning yet it may conflict with other valuable functionings in PwD’s lives, such as, being healthy, being safe, being stress-free, and being financially secure. Consequently, people may prioritize other functionings over travelling even when they have opportunities to travel. Therefore, whether someone travels or not is not only about what resources and conversion factors they have but also about what they value in their lives. The capability approach encourages researchers to evaluate travelling as one of many aspects of wellbeing and build more holistic and richer accounts of lives that PwD value and the part travel plays in them.

The capability approach and accessible tourism: policies and interdisciplinarity

With its flexible yet sophisticated conceptual framework, the capability approach ‘is one of those rare theories that strongly connects disciplines and offers a truly interdisciplinary language. And it leads to recommendations on how to organize society and choose policies that are often genuine alternatives for prevailing views’ (Robeyns, Citation2017, p. 18). This strength of the capability approach is clearly demonstrated through its application in international and national evaluative frameworks for human development, poverty, inequality, and wellbeing (e.g. the UNDP’s Human Development Reports) and critical policy analysis in various fields, such as, education (e.g. Van Aswegen & Shevlin, Citation2019), and social housing (e.g. Hearne & Murphy, Citation2019).

In the tourism literature, a relatively small number of studies have assessed accessibility/disability legislation, regulation, and accessible tourism policies (e.g. Darcy & Taylor, Citation2009; Morris & Kazi, Citation2016). With increasing interest in accessible tourism at both international and national levels (in the western world at least), review of such policies and other relevant public and social policies is much needed. Legislation and policies not only reflect the political will of governments but also influence the social attitudes towards PwD and therefore ‘the laws and norms that regulate the rights of tourists (with and without disabilities) are the main variables that affect the level of tourist accessibility’ (Porto et al., Citation2019, p. 180). Interdisciplinary thinking beyond tourism is essential in assessing accessible tourism policies and initiatives as ‘to contemplate disability is to scrutinise inequality’ (Goodley et al., Citation2019, p. 973) and PwD’s access to tourism cannot be considered in isolation from other social issues, such as, poverty and equality.

Policies are context dependent and value laden, informed by dominant ideas of a society (Yerkes et al., Citation2019). One such dominant idea highlighted by critical disability scholars (e.g. Campbell, Citation2009; Goodley, Citation2014; Wolbring, Citation2012) is ableism. Ableism refers to ‘ideas, practices, institutions and social relations that presume ablebodiedness, and by so doing, construct persons with disability as marginalised … and largely invisible “others”’ (Chouinard, Citation1997, p. 380). This normative ableist logic transcends through politics, laws, sciences, cultural values and dominates narratives in the society. By highlighting ableism, ‘the negative stereotypes and cultural values that surround disability and impairment can be challenged and focused away from the persons with impairment’ (Vehmas & Watson, Citation2014, p. 640).

Tourism scholars may join this discourse by scrutinizing ableism in accessible tourism and other relevant policies and practices. This calls for reflexivity and rethinking of the positionality of researchers in this area. Based on the capability approach, we can question if policies and projects are developed to expand PwD’s capabilities, or to meet another public policy goal (e.g. economic growth), or only to serve the interests of a dominant group (Robeyns, Citation2017). The capability approach offers tourism scholars with opportunities to join interdisciplinary conversations and contribute to challenging the dominant ableism, institutional, and structural discrimination. The capability approach is ‘essentially a “people-centred” approach, which puts human agency (rather than organizations such as markets or governments) at the centre of the stage’ (Drèze & Sen, Citation2002, p. 6) and can help in ‘progressing a socially oriented conceptualisation of disability’ (Van Aswegen & Shevlin, Citation2019, p. 640).

Conclusion

In this paper we present the capability approach as an overarching conceptual framework with relevance for accessible tourism research. We highlight the potential of the capability approach in advancing the theoretical development of the field of accessible tourism. So far, accessible tourism research has taken a mainly economic and social rights-based perspective in arguing for the need to address questions about the participation of persons with disabilities (PwD) in tourism, leisure, and recreational activities. While such a focus has done much for clarifying the challenges and opportunities for PwD’s participation, their agency and choices have not always been made central in research inquiries. The capability approach offers new conceptual grounds for accessible tourism research because it focuses

on what people are able to do and be, on the quality of their life, and on removing obstacles in their lives so that they have more freedom to live the kind of life that, upon reflection, they have reason to value. (Robeyns, Citation2005, p. 94)

We have shown the close alignment between the capability approach with the social model of disability, and the conceptual basis it offers for work focusing on social inclusion and equity for PwD in tourism, leisure, and recreational activities. We have identified three areas of accessible tourism research where the capability approach can help advance. Firstly, the capability approach brings more attention to the influence of non-market resources, such as support from families and disability organizations, and socio-economic conversion factors on PwD’s opportunities to travel. Secondly, the capability approach highlights PwD’s choices and agency both in the tourism context and regarding their broad wellbeing. In this way, the approach can contribute to a more holistic, nuanced, and richer understanding of the role of personal choice and agency – both real and perceived – in enabling and/or hampering PwD’s opportunities for travel and how such opportunities help them achieve functionings they value. Thirdly, the capability approach encourages accessible tourism scholars to critically examine accessible tourism and other relevant policies and initiatives, and to engage with more interdisciplinary inquiries to address social inequality.

The capability approach is a flexible and multi-purpose framework, rather than a precise theory (Alkire, Citation2005; Robeyns, Citation2017; Sen, Citation1992). Critics may call it ambiguous, but we are of the view that it is this open and underspecified nature that gives the capability approach its strengths. We illustrate how the capability approach offers a broad theoretical framework that can advance discussions in accessible tourism, but its more specific applications will depend on particular study purposes and contexts. One thing is clear though, and this is, to create valuable real opportunities to travel for PwD, it is necessary to involve PwD in research design, expressing and deciding what really matters to their lives and their personal wellbeing, and how travelling can play a part in it.

Future studies therefore can offer new perspectives in collecting information by listening to PwD with various disabilities, their families, caregivers, and disability organizations. The capability approach opens up avenues for research that focuses on, for example, the interpersonal comparison of capabilities of PwD and their families/caregivers for and through tourism; assessment of accessible tourism products against capabilities and functionings desired by PwD, based on their personal values, preferences and interest, not just their disabilities; investigation into how PwD achieve travelling by utilizing various resources, conversion factors, and agency; and assessment of how achieved travelling helps PwD build new capabilities and support their wellbeing over time. Such studies can assist scholars to build more complete knowledge of what truly matters to PwD across their life course and inform accessible tourism policies and product design.

There is also fruitful work to be done at the intersection between accessible tourism and social tourism, and between tourism and other relevant disciplines by addressing the links between disability and poverty, disability and social inclusion, and disability and wellbeing. Such interdisciplinary work can inform practices in other relevant fields, such as, therapeutic recreation and occupational health, and relevant policies and initiatives, strengthening the argument for the role of tourism in social inclusion and wellbeing of PwD.

Central to the capability approach is human diversity. Ultimately it focuses on what people are effectively able to do and be, to lead the lives they value. In giving prominence to PwD’s choices and agency, the capability approach is useful in dismantling dominant ableist discourse while making future accessible tourism research inquiries more participatory and inclusive. In effect the capability approach helps tourism scholars develop more comprehensive understanding of how tourism can help a person to lead a life they value regardless of their disability.

Acknowledgements

Emmanuel Akwasi Adu-Ampong acknowledges with appreciation the Dutch Research Council (NWO) Veni Grant with number VI.Veni.201S.037, that made his involvement of this current research project possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alkire, S. (2002). Valuing freedoms: Sen’s capability approach and poverty reduction. Oxford University Press.

- Alkire, S. (2005). Why the capability approach? Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/146498805200034275

- Alkire, S. (2015). Capability approach and well-being measurement for public policy. OPHI working paper 94. Oxford University.

- Alkire, S., & Deneulin, S. (2009). The human development and capability approach. In S. Deneulin & L. Shahani (Eds.), An introduction to the human development and capability approach (pp. 22–48). Earthscan.

- Bellucci, M., Biggeri, M., Nitti, C., & Terenzi, L. (2023). Accounting for disability and work inclusion in tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 98, 103526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103526

- Benjamin, S., Bottone, E., & Lee, M. (2021). Beyond accessibility: Exploring the representation of people with disabilities in tourism promotional materials. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(2–3), 295–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1755295

- Bhogal-Nair, A., Lindridge, A. M., Tadajewski, M., Moufahim, M., Alcoforado, D., Cheded, M., Figueiredo, B., & Liu, C. (2023). Disability and well-being: Towards a capability approach for marketplace access. Journal of Marketing Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2023.2271020.

- Blichfeldt, B. S., & Nicolaisen, J. (2011). Disabled travel: Not easy, but doable. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(1), 79–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500903370159

- Buhalis, D., & Darcy, S. (Eds.). (2011). Accessible tourism: Concepts and issues. Channel View Publications.

- Burnett, J. J., & Baker, H. B. (2001). Assessing the travel-related behaviors of the mobility-disabled consumer. Journal of Travel Research, 40(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750104000102

- Campbell, F. (2009). Contours of ableism: The production of disability and abledness. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Carneiro, M. J., Alves, J., Eusébio, C., Saraiva, L., & Teixeira, L. (2022). The role of social organisations in the promotion of recreation and tourism activities for people with special needs. European Journal of Tourism Research, 30, 3013. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v30i.2153

- Chiappero-Martinetti, E., Egdell, V., Hollywood, E., & McQuaid, R. (2015). Operationalisation of the capability approach. In H. U. Otto, R. Atzmüller, T. Berthet, L. Bifulco, J. M. Bonvin, E. Chiappero-Martinetti, V. Egdell, B. Halleröd, C. C. Kjeldsen, M. Kwiek, R. Schröer, J. Vero, & M. Zieleńska (Eds.), Facing trajectories from school to work: Towards a capability-friendly youth policy in Europe (pp. 115–139). Springer.

- Chouinard, V. (1997). Making space for disabling differences: Challenging ablcist geographies. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 15(4), 379–387. https://doi.org/10.1068/d150379

- Clark, D. (2005a). Sen’s capability approach and the many spaces of human well-being. Journal of Development Studies, 41(8), 1339–1368. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380500186853

- Clark, D. (2005b). The capability approach: Its development, critiques and recent advances, GPRG-WPS-032. ESRC Global Poverty Research Group.

- Cloquet, I., Palomino, M., Shaw, G., Stephen, G., & Taylor, T. (2018). Disability, social inclusion and the marketing of tourist attractions. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(2), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1339710

- Connell, J., & Page, S. J. (2019). Case study: Destination readiness for dementia-friendly visitor experiences: A scoping study. Tourism Management, 70, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.05.013

- Darcy, S., & Buhalis, D. (2011). Introduction: From disabled tourists to accessible tourism. In D. Buhalis & S. Darcy (Eds.), Accessible tourism: Concepts and issues (pp. 1–20). Channel View Publications.

- Darcy, S., Cameron, B., & Pegg, S. (2010). Accessible tourism and sustainability: A discussion and case study. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(4), 515–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003690668

- Darcy, S., & Dickson, T. (2009). A whole-of-life approach to tourism: The case for accessible tourism experiences. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 16(1), 32–44. https://doi.org/10.1375/jhtm.16.1.32

- Darcy, S., McKercher, B., & Schweinsberg, S. (2020). From tourism and disability to accessible tourism: A perspective article. Tourism Review, 75(1), 140–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-07-2019-0323

- Darcy, S., & Taylor, T. (2009). Disability citizenship: An Australian human rights analysis of the cultural industries. Leisure Studies, 28(4), 419–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360903071753

- Daruwalla, P., & Darcy, S. (2005). Personal and societal attitudes to disability. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(3), 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.10.008

- Devile, E. L., Eusébio, C., & Moura, A. (2023). Traveling with special needs: Investigating constraints and negotiation strategies for engaging in tourism activities. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-09-2022-0410

- Diekmann, A., McCabe, S., & Ferreira, C. C. (2018). Social tourism: Research advances, but stasis in policy. Bridging the divide. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 10(3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1490859

- Domínguez, T., Darcy, S., & Alén, E. (2015). Competing for the disability tourism market – A comparative exploration of the factors of accessible tourism competitiveness in Spain and Australia. Tourism Management, 47, 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.008

- Domínguez, T., Fraiz, J. A., & Alén, E. (2013). Economic profitability of accessible tourism for the tourism sector in Spain. Tourism Economics, 19(6), 1385–1399. https://doi.org/10.5367/te.2013.0246

- Drèze, J., & Sen, A. (2002). India: Development and participation (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Duignan, M. B., Brittain, I., Hansen, M., Fyall, A., Gerard, S., & Page, S. (2023). Leveraging accessible tourism development through mega-events, and the disability-attitude gap. Tourism Management, 99, 104766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104766

- Eichhorn, V., Miller, G., Michopoulou, E., & Buhalis, D. (2008). Enabling access to tourism through information schemes? Annals of Tourism Research, 35(1), 189–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.07.005

- Eichhorn, V., Miller, G., & Tribe, J. (2013). Tourism: A site of resistance strategies of individuals with a disability. Annals of Tourism Research, 43, 578–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2013.03.006

- Evans, J., & Collard, S. (2022). Facing barriers: Exploring the relationship between disability and financial wellbeing in the UK. Retrieved December 20, 2022, from https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/geography/pfrc/documents/Facing%20barriers.pdf

- Farkas, J., Raffay, Z., & Petykó, C. (2022). A new approach to accessibility, disability and sustainability in tourism – Multidisciplinary and philosophical dimensions. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites, 40(1), 319–326. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.40138-834

- Garda, B. (2022). Enabling accessible tourism: The case of Konya. Journal of Gastronomy, Hospitality and Travel, 5, 1021–1034.

- Gassiot, A., Prats, L., & Coromina, L. (2018). Tourism constraints for Spanish tourists with disabilities: Scale development and validation. Documents d'Anàlisi Geogràfica, 64(1), 49–71. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.364

- Gillovic, B., & McIntosh, A. (2015). Stakeholder perspectives of the future of accessible tourism in New Zealand. Journal of Tourism Futures, 1(3), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2015-0013

- Gillovic, B., & McIntosh, A. (2020). Accessibility and inclusive tourism development: Current state and future agenda. Sustainability, 12(22), 9722. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229722

- Gillovic, B., McIntosh, A., Darcy, S., & Cockburn-Wootten, C. (2018). Enabling the language of accessible tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(4), 615–630. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2017.1377209

- Goodley, D. (2014). Dis/ability studies: Theorising disablism and ableism. Routledge.

- Goodley, D., Lawthom, R., Liddiard, K., & Runswick-Cole, K. (2019). Provocations for critical disability studies. Disability & Society, 34(6), 972–997. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1566889

- Hansen, M., Fyall, A., Macpherson, R., & Horley, J. (2021). The role of occupational therapy in accessible tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 90, 103145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103145

- Happ, É., & Bolla, V. (2022). A theoretical model for the implementation of social sustainability in the synthesis of tourism, disability studies, and special-needs education. Sustainability, 14(3), 1700. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031700

- Hearne, R., & Murphy, M. (2019). Social investment, human rights and capabilities in practice: The case study of family homelessness in Dublin. In M. Yerkes, J. Javornik, & A. Kurowska (Eds.), Social policy and the capability approach: Concepts, measurements and application (pp. 125–146). Policy Press.

- Hick, R. (2012). The capability approach: Insights for a new poverty focus. Journal of Social Policy, 41(2), 291–308. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279411000845

- Ho, C. H., & Peng, H. H. (2017). Travel motivation for Taiwanese hearing-impaired backpackers. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 22(4), 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2016.1276464

- Hunter-Jones, P. (2004). Young people, holiday-taking and cancer—An exploratory analysis. Tourism Management, 25(2), 249–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00094-3

- Hunter-Jones, P. (2011). The role of charities in social tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 14(5), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2011.568054

- Hunter-Jones, P., Sudbury-Riley, L., Chan, J., & Al-Abdin, A. (2023). Barriers to participation in tourism linked respite care. Annals of Tourism Research, 98, 103508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2022.103508

- Hvinden, B., & Halvorsen, R. (2018). Mediating agency and structure in sociology: What role for conversion factors? Critical Sociology, 44(6), 865–881. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920516684541

- Innes, A., Page, S. J., & Cutler, C. (2016). Barriers to leisure participation for people with dementia and their carers: An exploratory analysis of carer and people with dementia’s experiences. Dementia (Basel, Switzerland), 15(6), 1643–1665. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301215570346

- Jackson, W. A. (2005). Capabilities, culture, and social structure. Review of Social Economy, 63(1), 101–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760500048048

- Jensen, M. T., Chambers, D., & Wilson, S. (2023). The future of deaf tourism studies: An interdisciplinary research agenda. Annals of Tourism Research, 100, 103549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2023.103549

- Kim, S., & Lehto, X. Y. (2013). Travel by families with children possessing disabilities: Motives and activities. Tourism Management, 37, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.12.011

- Lee, B. K., Agarwal, S., & Kim, H. J. (2012). Influences of travel constraints on the people with disabilities’ intention to travel: An application of Seligman’s helplessness theory. Tourism Management, 33(3), 569–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.06.011

- Lehto, X., Luo, W., Miao, L., & Ghiselli, R. F. (2018). Shared tourism experience of individuals with disabilities and their caregivers. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.04.001

- Mactavish, J. B., MacKay, K. J., Iwasaki, Y., & Betteridge, D. (2007). Family caregivers of individuals with intellectual disability: Perspectives on life quality and the role of vacations. Journal of Leisure Research, 39(1), 127–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2007.11950101

- Masala, C., & Petretto, D. R. (2008). From disablement to enablement: Conceptual models of disability in the 20th century. Disability and Rehabilitation, 30(17), 1233–1244. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701602418

- McCabe, S. (2009). Who needs a holiday? Evaluating social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(4), 667–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2009.06.005

- Merrick, D., Hillman, K., Wilson, A., Labbé, D., Thompson, A., & Mortenson, W. B. (2021). All aboard: Users’ experiences of adapted paddling programs. Disability and Rehabilitation, 43(20), 2945–2951. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2020.1725153

- Michopoulou, E., & Buhalis, D. (2013). Information provision for challenging markets: The case of the accessibility requiring market in the context of tourism. Information & Management, 50(5), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2013.04.001

- Minnaert, L. (2014). Social tourism participation: The role of tourism inexperience and uncertainty. Tourism Management, 40, 282–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.07.002

- Minnaert, L., Maitland, R., & Miller, G. (2011). What is social tourism? Current Issues in Tourism, 14(5), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2011.568051

- Mitra, S. (2006). The capability approach and disability. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 16(4), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/10442073060160040501

- Morgan, N., Pritchard, A., & Sedgley, D. (2015). Social tourism and well-being in later life. Annals of Tourism Research, 52, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.02.015

- Morris, S., & Kazi, S. (2016). Planning an accessible expo 2020 within Dubai’s 5 star hotel industry from legal and ethical perspectives. Journal of Tourism Futures, 2(1), 88–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2015-0020

- Moura, A., Eusébio, C., & Devile, E. (2023). The ‘why’ and ‘what for’ of participation in tourism activities: Travel motivations of people with disabilities. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(6), 941–957. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2044292

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2003). Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice. Feminist Economics, 9(2–3), 33–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570022000077926

- Nyman, E., Westin, K., & Carson, D. (2018). Tourism destination choice sets for families with wheelchair-bound children. Tourism Recreation Research, 43(1), 26–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2017.1362172

- Poria, Y., & Beal, J. (2017). An exploratory study about obese people’s flight experience. Journal of Travel Research, 56(3), 370–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516643416

- Porto, N., Rucci, A. C., Darcy, S., Garbero, N., & Almond, B. (2019). Critical elements in accessible tourism for destination competitiveness and comparison: Principal component analysis from Oceania and South America. Tourism Management, 75, 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.04.012

- Qiao, G., Ding, L., Zhang, L., & Yan, H. (2022). Accessible tourism: A bibliometric review (2008–2020). Tourism Review, 77, 713–730.

- Randle, M. J., Zhang, Y., & Dolnicar, S. (2019). The changing importance of vacations: Proposing a theoretical explanation for the changing contribution of vacations to people’s quality of life. Annals of Tourism Research, 77, 154–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.11.010

- Robeyns, I. (2005). The capability approach: A theoretical survey. Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/146498805200034266

- Robeyns, I. (2016). Conceptualising well-being for autistic persons. Journal of Medical Ethics, 42(6), 383–390. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2016-103508

- Robeyns, I. (2017). Wellbeing, freedom and social justice: The capability approach re-examined. Open Book Publishers.

- Robeyns, I. (2020). Wellbeing, place and technology. Wellbeing, Space and Society, 1, 100013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wss.2020.100013

- Rubio-Escuderos, L., García-Andreu, H., Michopoulou, E., & Buhalis, D. (2021a). Perspectives on experiences of tourists with disabilities: Implications for their daily lives and for the tourist industry (pp. 1–15). Tourism Recreation Research.

- Rubio-Escuderos, L., García-Andreu, H., & Ullán de la Rosa, J. (2021b). Accessible tourism: Origins, state of the art and future lines of research. European Journal of Tourism Research, 28, 2803–2803. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v28i.2237

- Scheyvens, R., & Biddulph, R. (2018). Inclusive tourism development. Tourism Geographies, 20(4), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2017.1381985

- Sedgley, D., Pritchard, A., Morgan, N., & Hanna, P. (2017). Tourism and autism: Journeys of mixed emotions. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 14–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.009

- Sen, A. K. (1985). Commodities and capabilities. Elsevier Science Publishers.

- Sen, A. K. (1992). Inequality reexamined. Clarendon Press.

- Sen, A. K. (1999). Development as freedom. Knopf Press.

- Sen, A. K. (2002). Rationality and freedom. Harvard University Press.

- Sen, A. K. (2004). Capabilities, lists, and public reason: Continuing the conversation. Feminist Economics, 10(3), 77–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570042000315163

- Sen, A. K. (2009). The idea of justice. Penguin.

- Shaw, G., McCabe, S., & Wooler, J. (2020). Social tourism in the UK: The role of the voluntary sector as providers in a period of austerity. In A. Diekmann & S. McCabe (Eds.), Handbook of social tourism (pp. 123–138). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Stewart, F. (2005). Groups and capabilities. Journal of Human Development, 6(2), 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649880500120517

- Stiglitz, J., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2009). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE).

- Stones, R. (2005). Structuration theory. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Suárez-Henríquez, C., Ricoy-Cano, A. J., Hernández-Galan, J., & de la Fuente-Robles, Y. M. (2022). The past, present, and future of accessible tourism research: A bibliometric analysis using the Scopus database. Journal of Accessibility and Design for All, 12, 26–60.

- Sylvester, C. (2011). Therapeutic recreation, the international classification of functioning, disability, and health, and the capability approach. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 45, 85–104.

- Tao, B. C., Goh, E., Huang, S., & Moyle, B. (2019). Travel constraint perceptions of people with mobility disability: A study of Sichuan earthquake survivors. Tourism Recreation Research, 44(2), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2019.1589085

- Tomej, K., & Duedahl, E. (2023). Engendering collaborative accessibility through tourism: From barriers to bridges. Annals of Tourism Research, 99, 103528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2023.103528

- Trani, J. F., Bakhshi, P., Bellanca, N., Biggeri, M., & Marchetta, F. (2011). Disabilities through the capability approach lens: Implications for public policies. Alter, 5(3), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2011.04.001

- Van Aswegen, J., & Shevlin, M. (2019). Disabling discourses and ableist assumptions: Reimagining social justice through education for disabled people through a critical discourse analysis approach. Policy Futures in Education, 17(5), 634–656. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318817420

- Vehmas, S., & Watson, N. (2014). Moral wrongs, disadvantages, and disability: A critique of critical disability studies. Disability & Society, 29(4), 638–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2013.831751

- Visit Britain. (n.d.). The value of the purple pound. https://www.visitbritain.org/business-advice/value-purple-pound

- Winter, T., & Kim, S. (2021). Exploring the relationship between tourism and poverty using the capability approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(10), 1655–1673. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1865385

- Wise, J. B. (2018). Integrating leisure, human flourishing, and the capabilities approach implications for therapeutic recreation. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 52(3), 254–268. https://doi.org/10.18666/TRJ-2018-V52-I3-8479

- Wolbring, G. (2012). Expanding ableism: Taking down the ghettoization of impact of disability studies scholars. Societies, 2(3), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc2030075

- World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health. World Health Organization. Retrieved August 8, 2022, from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42407/9241545429.pdf?sequence=1

- World Health Organization. (2023). World Health Organization fact sheets on disability. World Health Organization. Retrieved November 13, 2023, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health

- Yau, M. K. S., McKercher, B., & Packer, T. L. (2004). Traveling with a disability: More than an access issue. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(4), 946–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.03.007

- Yerkes, M., Javornik, J., & Kurowska, A. (2019). Rethinking social policy from a capability perspective. In M. Yerkes, J. Javornik, & A. Kurowska (Eds.), Social policy and the capability approach: Concepts, measurements and application (pp. 1–18). Policy Press.

- Zahari, N. F., Kamarudin, H., Zawawi, Z. A., Rashid, R. A., & Bahari, M. M. (2023). Heritage tourism: A disabled person’s rights to engage in social activity. Planning Malaysia, 21, 484–494. https://doi.org/10.21837/pm.v21i25.1252

- Zajadacz, A. (2015). Evolution of models of disability as a basis for further policy changes in accessible tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures, 1(3), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-04-2015-0015

- Załuska, U., Kwiatkowska-Ciotucha, D., & Grześkowiak, A. (2022). Travelling from perspective of persons with disability: Results of an international survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10575. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710575