ABSTRACT

Engagement in tourist experiences is essential for destination development. However, how tourist engagement generates positive psychological outcomes, such as tourist well-being, remains underexplored. Consequently, drawing on an interpretivist paradigm, this study conducts in-depth focus groups with 23 tourism professionals to explore the mechanism through which engagement in tourism experiences is enhanced and subsequently influences tourist well-being. Findings indicate three key pull factors (accessible facilities, available information and accomplished services) which enable tourists to negotiate intrapersonal barriers, fostering behavioral, cognitive and emotional engagement in tourism experiences. With the accumulation of multidimensional engagement experiences, tourists reaped enhanced tourist well-being. A Triple-A model is developed from this study to depict the dynamic connection among the pull factors of tourist engagement, intrapersonal barriers negotiation and tourist well-being. Future studies should seek to strengthen emerging empirical evidence which can inform policy intervention designed to demonstrate the efficacy of tourism experiences for enhancing tourist well-being.

1. Introduction

The well-being of the global population has become a significant concern, with the United Nations claiming healthy lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages as a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 3) (United Nations, Citation2015). The disruption in most human activities and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic (Williamson et al., Citation2022) (2019–2023) may produce a second and more profound and long-lasting pandemic, a ‘mental health crisis’ (Choi et al., Citation2020). In response, various multidisciplinary research activities have been launched to improve individuals’ mental health and well-being towards achieving SDG 3 by 2030 (Zyoud, Citation2023).

Tourism has emerged as a compelling avenue for enhancing human mental health and psychological well-being (Buckley, Citation2019; Filep & Laing, Citation2019). Simultaneously, the COVID-19 pandemic has heightened people’s awareness of maintaining well-being, leading to projections of a robust 12.4% annual growth in the global wellness tourism market from 2023 to 2030 (Liao et al., Citation2023; ReportLinker, Citation2023). Indeed, people are happier during travel than at home (McCabe & Johnson, Citation2013; Vada et al., Citation2019). It is also well-accepted that participating in travel activities enables the satisfaction of psychological needs, which in turn, leads to psychological well-being (Gupta et al., Citation2023; Vada et al., Citation2023). Tourist psychological well-being encompasses the accumulation of happy moments and the promotion of human flourishing (Filep et al., Citation2024). It has been linked to improved physical health outcomes, reinforced destination loyalty, and increased travel consumption (Patterson & Balderas, Citation2020; Steptoe et al., Citation2015; Vada et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, well-being research in tourism has been criticised as being atheoretical (Chang et al., Citation2022; Filep et al., Citation2024).

Some of the most prominent well-being models in the tourism literature such as PERMA (Seligman, Citation2011) and DRAMMA (Newman et al., Citation2014) models which have been borrowed from the positive psychological discipline to provide a better understanding of how different aspects of tourism experiences may influence well-being (Laing & Frost, Citation2017). Recently, Filep et al. (Citation2024) developed a tourism well-being model termed DREAMA which proposes five dimensions conceptualising tourist well-being – detachment-recovery (DR), engagement (E), affiliation (A), meaning (M), and achievement (A). Whilst existing studies have focused on how the dimensions of detachment-recovery, affiliation, meaning and achievement contribute to tourist well-being (e.g. Alrawadieh et al., Citation2021; Chen et al., Citation2016; Smith & Diekmann, Citation2017; Vada et al., Citation2022), the role of engagement in tourism experiences in generating positive psychological outcomes remains underexplored and conceptually underdeveloped.

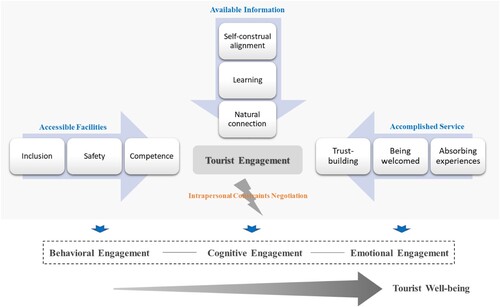

Engagement denotes a deeper level of involvement or immersion in experiences as a result of interactions between consumers and the objects (Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2021). In tourism, the objects are typically intangible and involve thoughts (cognitive) and feelings (affective) evaluations of an experience such as interactions with people (e.g. between the customer and tour guide) and participation in activities (e.g. the feeling of snorkeling on a reef). The opportunity to engage in tourism experiences is crucial not only for generating revenue but also for promoting social equality (Bianchi & de Man, Citation2021). For this reason, developing a deep understanding of elements that trigger or constrain consumer engagement in the context of tourism is needed (So et al., Citation2020). Consequently, this research draws on established and emerging positive psychological well-being models and leisure constraints theory to explore how pull factors (objects) in tourism destinations enhance tourists’ engagement and subsequently contribute to well-being. By synthesising the interview outcomes from 23 tourism professionals with the findings from conceptually related empirical research, a conceptual model – termed by this study as the Triple-A model – is developed to illustrate the connection between pull factors for tourists’ engagement in tourism experiences and psychological well-being.

The Triple-A model integrates multidisciplinary perspectives on tourist engagement, drawing from leisure constraints theory and psychological well-being models. In doing so, it extends the conceptualisation of engagement, an undervalued but imperative concept in understanding the well-being of tourists. The findings intend to inform destination planning, policy and service design to empower a broader group of people to engage in tourism experiences and experience the related well-being outcomes. This, ultimately, aligns with and contributes to the advancement of SDG 3 which emphasises enhancing human health and well-being (United Nations, Citation2015). The following section overviews the literature on positive psychology and how it relates to tourism well-being and engagement.

2. Literature review

2.1. Positive psychology, tourist well-being and engagement

Positive psychology is commonly regarded as the science of well-being and studies what makes human functioning optimal (Kern et al., Citation2020; Sirgy, Citation2019; Uysal et al., Citation2016). Thus, this area of research highlights the positive aspects of how people behave and perceive life (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2020). The concept of well-being has its roots in philosophical schools of thought, namely hedonia and eudaimonia (Lambert et al., Citation2015). The hedonic dimension of well-being focuses on the pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain, emphasising immediate satisfaction and positive emotions such as pleasure, relaxation and contentment (Vada et al., Citation2020). The eudaimonic well-being centres on the realisation of one’s potential, involving personal growth, the development of meaningful relationships, fulfilling one’s capabilities and having a greater purpose in life (Huta, Citation2013; Sirgy & Uysal, Citation2016). Together, these hedonic and eudaimonic well-being dimensions provide a holistic and comprehensive framework for understanding the intricate nature of human flourishing (Filep et al., Citation2024).

Prior research shows that travel has the potential to produce positive psychological benefits (Filep & Laing, Citation2019; Neal et al., Citation2007). Research also suggests that travellers are usually happier than non-travellers (Rátz & Michalkó, Citation2011). The conceptual mechanisms linking travel activities and psychological well-being have been explained through the adoption of influential theories (Sirgy et al., Citation2017) including the broaden and build theory (Fredrickson, Citation2004), flow theory (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2020) and self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). Notably, the theory of flow initially links the optimal experience of deep immersion and engagement in tourism activity, resulting in profound satisfaction and fulfillment. Commonly described as being ‘in the zone’, this state is achieved when individuals are completely absorbed in a task that presents a balanced challenge to their skills (Wesson & Boniwell, Citation2007). However, the conceptualisation of tourist psychological well-being has been critiqued for being dichotomous as a single perspective may not fully capture the psychological benefits of tourism experiences (Filep & Laing, Citation2019). To address this concern, hybrid models such as PERMA (Seligman, Citation2011), and DRAMMA (Newman et al., Citation2014), which encapsulate both hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions have been proposed (Laing & Frost, Citation2017).

The PERMA model illustrates five building blocks of well-being: positive emotions (P), engagement (E), relationships (R), meaning (M) and achievement (A). It is used by tourism researchers to explain the psychological benefits derived from tourism experiences (Filep & Laing, Citation2019). For example, Zhou et al. (Citation2021) adopted the PERMA model to analyse hedonic and eudaimonic well-being of different roles, including the paraders, volunteers and organisers, at an LGBT event. The dimensions drawn from the PERMA model were also identified through women’s travel narratives in Italy (Laing & Frost, Citation2017). In this study, Laing and Frost (Citation2017) also used the DRAMMA model to frame the triggers promoting tourist well-being. The DRAMMA mechanisms include detachment-recovery (DR), autonomy (A), mastery (M), meaning (M) and affiliation (A).

To further contextualise these multidimensional models into a tourism field, Filep et al. (Citation2024) developed DREAMA model (detachment-recovery (DR), engagement (E), affiliation (A), meaning (M), and achievement (A)) by integrating PERMA and DRAMMA. The DREAMA model extends beyond PERMA and DRAMMA by applying the affiliation (relationship) dimension to both social and natural environments (Lee et al., Citation2024), singling out the positive link between tourists and the natural environment (Huang et al., Citation2019). Additionally, DREAMA synthesises, and combines the overlapping dimensions of the two models, and extrapolates key subdimensions. For example, the concept of autonomy (A) in the DRAMMA model is argued to align with engagement (E) in the PERMA framework (Filep et al., Citation2024). Despite the extant insight, the role of engagement in travel experiences and its specific conceptual associations with psychological well-being remains unclear (Rather, Citation2020).

2.2. Multidimensionality of tourist engagement

The concept of engagement spans various academic fields, including psychology, organisational behaviour, sociology, and marketing (Hollebeek et al., Citation2019; Kumar et al., Citation2019; Verhoef et al., Citation2010). However, the exploration of engagement within specific contexts, such as on-site tourism experience, remains limited (Harrigan et al., Citation2017). Current insights into tourist engagement are primarily derived from consumer behaviour research (Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2021) where, consumer (tourist) engagement is conceptualised as the interactive encounters with surroundings and other stakeholders (Brodie et al., Citation2011).

Yet, within the literature, there is a lack of consensus regarding the definition of consumer engagement and the concepts that underpin it (Hao, Citation2020). Chen et al.’s (Citation2021) systematic review of consumer engagement in hospitality and tourism literature identified two categories of definitions: unidimensional and multidimensional. The unidimensional perspective focuses mainly on behavioural involvement, whereas the multidimensional view emphasises the synthesis of cognitive, emotional and behavioural investment (Chen et al., Citation2021).

Studies by So et al. (Citation2016), Hao (Citation2020) and Rasoolimanesh et al. (Citation2021) highlight the omission of focusing solely on the behavioural component when examining tourist engagement. Subsequently, a multidimensional view of engagement in tourism is prevailing. Combining existing perspectives, this study adopts a comprehensive definition of tourist engagement that includes cognitive, emotional, and behavioural dimensions (So et al., Citation2014). Specifically, the cognitive dimension relates to a tourist’s thought process and depth of reflection about an activity; The emotional dimension denotes the positive affection or attachment tourist experiences during an activity; The behavioural dimension signifies the energy, effort, and time a tourist dedicates to exploring a destination and participating in activities (Hollebeek et al., Citation2014).

2.3. Triggers and constraints to tourist engagement

Previous studies have highlighted the positive outcomes of tourist engagement at destinations, including increased trust in the destination, loyalty, and value co-creation (Rather et al., Citation2019). Given the significance of such destination performance, the triggers of tourist engagement have garnered considerable interest among scholars (Prentice et al., Citation2019). However, much of the existing research in tourism focuses on online engagement, such as interactions with social media platforms, online communities, and websites (Chen et al., Citation2021). For example, Buhalis and Sinarta (Citation2019) suggests that tourism brands can leverage almost constant connectivity through social media to cultivate consumer engagement and build interactions with potential tourists. Yet, customer engagement research in the offline context is relatively scarce (Chen et al., Citation2021).

Extant studies that examine the triggers of offline tourist engagement were mainly grounded on pull-based factors as tourism providers’ efforts, and push-based factors as customers’ intrinsic needs (Chen et al., Citation2021; Yiamjanya & Wongleedee, Citation2014). Correspondingly, tourists may also face obstacles that constrain engagement in travel experiences. From a tourism providers’ perspective, these barriers often stem from inadequate facilities, an insecure environment, limited availability of resources, or poor staff attitude (Cole et al., Citation2019; Figueiredo et al., Citation2012; Sisto et al., Citation2022). From tourists’ intrinsic perspective, barriers to engagement include perceived risk, limited knowledge, and lack of interest (Chathoth et al., Citation2014; Gu & Huang, Citation2019). Despite the bilateral insights, an integrated perspective is imperative which incorporates pull factors offered by tourism providers and barriers faced by individuals (Gu et al., Citation2020; Heinonen, Citation2018). This nuanced view is critical to acquire a deeper understanding of how to enhance tourist engagement in experiences.

Leisure constraints theory offers insight into how tourists can overcome perceived barriers to participation. It suggests that if the barriers preventing people from travelling are negotiated, non-participants may become participants in tourist experiences (Crawford & Godbey, Citation1987). Lower levels of constraints tend to result in higher levels of participation and engagement (Nyaupane & Andereck, Citation2008). Consequently, constraint negotiation plays a vital role in tourist engagement in experiences.

Previous research suggested three types of travel constraints: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and structural (Crawford & Godbey, Citation1987). Intrapersonal constraints refer to the internal factors at a psychological or cognitive level, including stress, depression, anxiety, religiosity, perceived self-skill, and lack of interest. Interpersonal constraints are social constraints which arise when an individual lacks companions in travel. Structural constraints encompass physical or operational restrictions, such as limited financial resources, lack of time and insufficient places to visit (Crawford & Godbey, Citation1987; Shin et al., Citation2022). The hierarchical theory of leisure constraints suggests that the first level – that is, intrapersonal constraints – are considered the most powerful constraints that need to be negotiated first (Crawford et al., Citation1991; Zhang et al., Citation2016).

Consequently, this study draws upon the multidimensional conceptualisation of tourist engagement and integrates it with positive psychological perspectives of well-being and the leisure constraints theory to advance understanding of the relationship between engagement and well-being in the tourism experience. In doing so, this study intends to address the following research objectives:

To critically identify and assess the pull factors in tourism destinations critical to negotiate travel constraints and enhance engagement in tourism experiences;

To develop a conceptual model that illustrates the dynamic relationship among pull factors for travel engagement, travel constraints negotiation and tourist well-being.

3. Methodology

Previous research on tourism and well-being has predominantly adopted quantitative methods (Vada et al., Citation2020), however, there is a call for qualitative studies to delve into the richness of how tourists perceive well-being from different experiences (Chang et al., Citation2022; Filep & Laing, Citation2019). Consequently, given the exploratory nature of the research objectives, this study adopts an interpretivist qualitative perspective to gain an in-depth understanding of how tourists perceive well-being outcomes from engagement in tourism (Chang et al., Citation2022; Vada et al., Citation2020).

3.1. Data collection

Data was collected via three focus group discussions with 23 tourism professionals (12 males and 11 females) who were local community leaders, business entrepreneurs, managers of non-profit organisations/non-government organisations (NGOs) or occupied in academia and government. The 23 tourism professionals were visiting Australia on an international programme and were requested to participate in this study. Prior to visiting Australia and, again, upon arrival in Australia, participants were briefed on the research aim and data collection protocol. Specifically, they were asked to observe elements that influence their well-being experiences during travel in Australia. The various tourism attractions included nature-based tourism experiences, heritage and indigenous attractions, and a wildlife park.

Following their visits to different tourism attractions, focus group discussions were organised. Focus group discussion was the most suitable approach for this study due to two key reasons. Firstly, participants of this study share similar characteristics such as ethnicity and social class background hence are more likely to fully engage in group discussion, which is crucial for generating rich and extensive opinions (Khalil et al., Citation2020). Secondly, focus group discussion allows researchers to act as ‘facilitators’ rather than ‘investigators’ as in one-on-one interviews. This role enables effective interaction between participants about the results of the observation and encourages in-depth discussion of the meanings that lie behind their common experiences in Australia (O. Nyumba et al., Citation2018).

The focus group discussions took place in October 2022 in Australia, coordinated by the first and second authors who have an ongoing programme of research on tourist well-being (Burrows & Kendall, Citation1997). The second author is central to the discussion by prompting the discussion and creating a relaxed talking environment, while the first author is in charge of documenting the discussion and observing non-verbal interactions (Rabiee, Citation2004). Participants were divided into three groups, each consisting of five to nine people (Burrows & Kendall, Citation1997; Krueger & Casey, Citation2000). As suggested by Hennink et al. (Citation2019), for participants with similar social backgrounds, two groups provided a comprehensive understanding of issues, and it is generally accepted that between four and fifteen participants in each group are suitable (O. Nyumba et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, evidence showed that mixed-gender groups tend to improve the quality of discussions and outcomes (Burrows & Kendall, Citation1997; O. Nyumba et al., Citation2018), hence each group encompassed both genders.

Focus groups commenced with a recap of the purpose of the current study. The focus group discussion interview questions were adapted from So et al.’s (Citation2014) tourism customer engagement scale and the DREAMA model (Filep et al., Citation2024). Initial questions include ‘In what attractions were you interested? Why?’ ‘Please describe a moment when you feel carried away or forgot about everything around you.’ ‘What factors during this travel influence your well-being?’ Participants were prompted to elaborate in further detail. With the subsequent articulation of group members, a clear pattern emerges and no new information covering a larger topic is identified when running the third group discussion, hence theoretical saturation is announced (Krueger, Citation1994). Each session was approximately one hour in duration, consistent with O. Nyumba et al. (Citation2018).

3.2. Data analysis

Following focus group discussions, the first author initially transcribed the recording with the software Otter ai (Williams et al., Citation2023), and listened and re-read the transcripts line by line in order to ensure the quality of the data. Transcripts were imported into NVivo qualitative data analysis software for further analysis (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2011). Subsequently, an open, axial and selective coding approach was selected to interpret deeper theoretical meanings (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). Open coding was conducted through a line-by-line reading of interview transcripts and coding of key ideas, expressing data and phenomena in the form of concepts (Williams & Moser, Citation2019), Axial coding was subsequently utilised to single out emerging themes and identify connections between open codes, with the purpose of developing categories (Strauss, Citation1998). Selective coding generated a higher level of abstraction which ultimately led to the formulation and elaboration of how engaged tourism experiences contribute to tourist well-being (Flick, Citation2009).

To improve credibility of the coding process (Palaganas et al., Citation2017), a panel of three experts with significant knowledge and experience in tourist well-being and accessibility studies reviewed and discussed the coding results (Dillette et al., Citation2019). The first author worked on open and axial coding independently whilst the second researcher reviewed the coding results (Dillette et al., Citation2019). If disagreement occurred, the first two researchers negotiated with each other and only occasionally needed to seek the third researcher’s assessment (Huang et al., Citation2019). The coding process and examples were shown in the Appendix. An audit trail was adopted to ensure the trustworthiness of the data: the second author delivered an online presentation of the preliminary research findings to the 23 participants in January 2023. This provided an opportunity to cross-check the accuracy of the data and validate the initial findings with participants. Following recommendations by Heaton (Citation2022), the pseudonym of tourism professionals (TP) was applied to preserve the privacy and anonymity of the respondents.

4. Results

Accessible facilities, available information and perceptions of high-quality accomplished services were identified in this study as the three key themes to enhance tourist engagement across behavioural, cognitive and emotional dimensions. This study found that these themes, in turn, have potential links to positive well-being outcomes. The following analysis explains the key findings relating to each of these factors.

4.1. Accessible facilities – inclusion, safety and competence

Easy access to facilities is reported to enhance visitors’ engagement in tourism experiences through delivering a sense of inclusion, perceived safety and competence. A sense of inclusion occurs when tourists are provided with resources, security and information to access the tourism experience regardless of their abilities. This sense of inclusion eliminates barriers to fully engaging with the environment (Riley & White, Citation2016), facilitating flourishing (Boyle et al., Citation2023). Participants noted that facilities accessible to diverse age groups and abilities foster this inclusion, exemplified by one saying, ‘I love how the government built the facility because it can be used for all the groups and all ages’ (TP01). Therefore, ‘everybody of any ability was able to go to the place, like the wetland forest, and enjoy the view’ (TP04). The importance of inclusion is further illustrated when a participant observed,

They built the trail in a flat in the corner because they want parents to go there with their children. It’s very simple but useful … I took a picture as I was impressed when I saw a parent bringing their baby. The trail is so accessible, both for children also for disabilities. (TP18)

Easy access to facilities significantly transformed the experiences of potential visitors who were initially reluctant to engage in certain tourism activities. These accessible amenities addressed intrapersonal constraints like anxiety and perceived safety concerns, leading to a noticeable shift in visitor attitudes and well-being. For instance, TP20, who is ‘not an outdoor person’ (TP20), had a preconceived notion about the difficulty of accessing natural sites:

In my perception, going to the National Park or going to the jungle, is difficult with difficult access. It’s not nice to the shoes, difficult to step and etc. [However], when I arrived, there’s a path for the cutting, very easy. (TP20)

Similarly, the high-quality facilities helped those with a fear of height to ‘be brave enough’ (TP23) to engage in activities. As TP23 remarked, ‘I feel convinced to take the Skyrail that I can do this because I trust that the facilities have a good quality’ (TP23). The perceived safety of the facilities enables participants to challenge themselves and generate a sense of competence. This feeling resonated with another participant, adding that ‘I conquered my fear of heights and I am pretty reliant on the safety of Australian experiences’ (TP20). Engagement in such challenging activities was facilitated by the perceived safety of the facilities, enabling the generation of a feeling of achievement, as participants narrated, ‘after that right away I text my daughter that I saw that sense of achievement’ (TP20) and ‘we can get very aware of something like, ‘I can’’ (TP07). Overall, the ease of access to facilities at the destination allowed visitors to negotiate their psychological and cognitive barriers such as anxiety and perceived unsafety, resulting in increased behavioural engagement. This further contributes to the hedonic well-being of pleasure and enjoyment, and a pivotal dimension of eudaimonic well-being – the sense of competence.

4.2. Available information – self-construal alignment, natural connection and learning

A second prominent theme is the availability of tourism information, which is essential in facilitating tourists’ engagement in experiences through aligning their self-construal types, offering learning opportunities, and fostering connection with nature. Self-construal refers to individuals’ perceptions of their connections with others, categorised as either independent or interdependent (Luan et al., Citation2023). Those with independent self-construal value autonomy and prefer social distancing, while those with interdependent self-construal emphasise relationships and closer interactions (Peker et al., Citation2018). Participants, especially those with independent self-construal, can be more naturally drawn into the destination surroundings when there was accessible and easily discernible information, such as well-placed signage, interpretive displays, and informative visitor centres. As articulated by a participant,

Maybe no one will need to talk too much, because I just see the sign and follow the next. I think it is good, as when people like me who are afraid to ask somebody or don’t want to get close to check all, they just can go to one place that provides all of the information. (TP07)

Specifically, in nature-based destinations, detailed information enhances visitors’ connection to the environment. Participants noted that

There are so many signages offered by the government and the national park or even the rain forest. They talk to everybody about the level of hills or the level of the river and then not jumping into waves … you cannot go that way and you can do this thing. (TP04)

Tour guides also play a pivotal role in enriching tourist well-being by facilitating cognitive engagement through conveyed knowledge. This is exemplified by a participant who recounted a significant learning moment: ‘The message really touched my mind that I learned I don’t have to do anything when the tree went down, just let it happen, because the forest is doing the right things for the ecological system.’ This information processing prompts a deep cognitive engagement and reflection: ‘That message really amazed me. Oh, I need to change the way how to behave toward nature’ (TP23). Such cognitive reflection is echoed by other participants, retrospecting that

I learned about the connection between nature and our health, like if we take a deep breath and go around forest 10 minutes a week, it’s really good for health. Then I think I will try it and just relax and enjoy it. (TP02)

4.3. Accomplished service – trust-building, being welcomed and absorbing experiences

Findings depict the impact of proficient service on tourists’ engagement, emphasising the expertise and capability of staff as crucial for trust-building, feeling welcomed, and absorbing experiences. For instance, proficiency in operating and managing various modes of transportation significantly improved the experience of visitors who have certain access limitations, such as those who experience seasickness. This allowed participants to build their trust and improve confidence to engage in experiences. One participant described the skill of the staff during a boat ride, narrating that,

On the way to the scene it was like surfing on the boat. It was scary, but the guys held up the surfs. You can still sit like this, even though some of us got seasick, but you felt safe, and you can enjoy the scenery on the way. (TP05)

Responsive staff members are essential in creating a relaxed and welcoming atmosphere that enhance visitors’ engagement in experiences at destinations. For instance, in the open ceremony on the first day of their arrival, the participant ‘was really impressed with one of the indigenous people coming and welcoming us in their language. And then we feel that we are totally accepted to come to Australia’ (TP13). The feeling of being welcomed and accepted fosters tourists’ emotional connection with place and space, evidenced by TP14 who added, ‘This is also related to what we are earning on the week, friendly to everyone, welcome me and send me off’ (TP14). In addition, the friendly interactions with the indigenous tourism workers further elicit the participants’ reflection on ‘how people live in Australia love people from a lot of countries or ethnic and respect each other’ (TP17). This strengthens their emotional engagement with the destination, especially as a visitor from a different country and ethnicity, as another remarked that ‘I feel more relatable on Australia’ (TP20). This sense of attachment and connection is closely linked to the eudaimonic aspects of well-being.

The accomplished service from the interpreter also helps navigate specific constraints like a lack of interest in attractions, triggering deeper engagement and even a flow state during experiences. The ‘passionate and infectious means of narrative’ (TP11) captures the participant’s attention and evokes their interest, which leads to the feeling when they ‘spent about one hour getting into the forest … it doesn’t really feel like an hour already passed, because the way she narrates and describes what happened there is pretty interesting’ (TP11). This perception of time flying reflects the flow state, a concept from the flow theory, where an individual being completely involved in an activity (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2020). The interpreter’s delivery with ‘energy and inspiration’ (TP22), not only captures attention but also emotionally connects visitors to the experience: ‘the patience when she tells us stories about the nature touched my heart. The passion, the spirit and the emotion she has get us charged for the positive energy’ (TP10), which contributes to the emotional engagement to ‘an amusing experience’ (TP10). Overall, the accomplished service from tourism workers builds trust, foster visitors’ sense of being welcomed, and facilitates the experience of absorption and flow state, thereby contributing to both hedonic and eudaimonic well-being of tourists.

5. Discussion

The analysis of the data generated three key themes that serve to reinforce engagement with travel experiences and well-being, specifically accessible facilities, available information and accomplished service. These pull factors are fundamental in negotiating intrapersonal travel constraints and generating well-being through facilitating engaging tourism experiences. The accessibility of facilities enhances visitors’ behavioural engagement by fostering a sense of inclusion, safety and competence. Providing available comprehensive information is vital for promoting tourists’ cognitive engagement as it aligns their self-construal types, offers learning opportunities, and strengthens their connection with nature. Accomplished service contributes to tourists’ emotional engagement through trust-building, creating a welcoming environment, and generating absorbing experiences. The ensuing discussion draws on the three emerging themes in combination with leisure constraints theory and conceptions of well-being embedded in positive psychology to develop the Triple-A model. The model depicts the relationship between pull factors, travel engagement and tourist well-being.

Findings reveal that the easily accessible facilities perceived as safe and inclusive enhance participation in activities at unfamiliar locations, thereby mitigating intrapersonal barriers such as perceived unsafety and uncertainty. This, in turn, facilitates the experience of hedonic emotions derived from engagement in tourism experiences. Consequently, the experience of novelty in a safe and inclusive environment encourages tourists’ engagement in activities that challenge one’s limits, enhancing their sense of competence – an eudaimonic dimension of well-being. This aligns with the Self-Determination Theory which argues that competence is a crucial element of human motivation (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000), and provides insights into how accessible facilities help overcome intrapersonal constraints and facilitate competence. Additionally, the research adds value to conceptually related literature on leisure constraints (Lam et al., Citation2020), indicating that insufficient facilities and inaccessible infrastructure create barriers that can inhibit engagement. Such findings reinforce the perspective that individuals who are not currently engaged in travel may become tourists when constraints are addressed or removed (Wan et al., Citation2022).

Self-construal significantly influences consumer behaviour (Gardiner et al., Citation2023), yet, it has been underexplored in research on tourist engagement (Su et al., Citation2022). This study highlights that visual information suits the preferences of independent tourists by reducing potential social anxiety and minimising cognitive disruptions hence promoting their engagement in experiences. In contrast, interactive information caters to the preference of interdependent tourists for close social connection, enhancing their engagement in tourism activities. This observation aligns with findings by Moses et al. (Citation2018), which indicate that individuals with a high interdependent self-construal have more immersive experiences in environments that foster social connections. Furthermore, learning, a cognitive process, can be facilitated through engagement with informative materials about tourism destinations. Available information about the destination environments encourages tourists to reflect cognitively on their connection with nature, fostering a sense of closeness. Such a connection is associated with individual well-being, especially the eudaimonic aspects (Chang et al., Citation2024). According to Lam et al. (Citation2020), who identified knowledge constraints as a significant barrier to visitor engagement and interest, this study suggests that available tourism information at destinations can potentially address unfamiliarity and lack of knowledge about the surroundings, subsequently enhancing cognitive engagement.

Service quality is a critical precursor to consumer engagement (Hapsari et al., Citation2017). This research demonstrates that tourism workers who demonstrate proficient capabilities in creating a reliable and welcoming environment are able to build trust with tourists and foster an emotional attachment between tourists and the destination. These emotional connections in turn enhance visitors’ engagement in experiences, supporting the notion that trust and rapport with service providers predict higher levels of customer engagement (Sim & Plewa, Citation2017). Furthermore, this research highlights the fundamental importance of high-quality interpretation which involves not only the content conveyed but also the manner of narration. An attractive and passionate interpretation enables tourists to connect emotionally and experience a state of flow, characterised by a delightful sensation of losing track of time due to deep immersion in the activity (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2020). Trust in the service provider and emotional connection to the place and activities potentially negotiate the intrapersonal constraints, such as lack of interest or perceived uncertainty, thereby contributing to a higher level of engagement (Kim & Barber, Citation2022), and is further linked to human well-being (Basu et al., Citation2020; Vada et al., Citation2023).

Combining empirical findings with new and established theoretical perspectives on engagement, leisure constraints and tourist well-being (Chen & Rahman, Citation2018; Filep et al., Citation2024), this research contributes the Triple-A Conceptual Model of tourist engagement and tourist well-being designed to extend our understanding of the relationship between pull factors of tourist engagement and tourist well-being ().

As displayed in , the pull factors of tourist engagement in experiences are comprised of three key elements, specifically, accessible facilities (in enhancing inclusion, safety and competence), available information (in fostering self-construal alignment, natural connection and learning), and accomplished service (in facilitating trust-building, being welcomed and absorbing experiences). Accessible facilities, as positioned on the left of the model, enable individuals of varying ages, families with children, and first-time tourists to equally access tourism offerings. The easy access to well-constructed facilities supports the negotiation of tourists’ certain intrapersonal constraints, such as perceived unsafety, uncertainty and anxiety, thereby expanding the pool of behavioural engagement of potential tourists (Wan et al., Citation2022). Available information, positioned at the top of the model, facilitates the alignment of self-construal and provides tourists with a deeper understanding of the place and environment. This not only helps overcome constraints such as lack of knowledge and interest but also enhances visitors’ connection and cognitive engagement with the destination (Chaulagain et al., Citation2021). Accomplished service, positioned on the right of the model, fosters tourists’ emotional connection with the place and trust in the service provider, thereby alleviating perceived uncertainty and concerns about safety. Additionally, proficient interpretative skills enable visitors to fully immerse in the experience and achieve a state of flow. Combined, these three elements effectively facilitate tourists in negotiating intrapersonal constraints, fostering their behavioral, cognitive and emotional engagement respectively. This, in turn, leads to heightened tourist well-being encompassing hedonic aspects such as pleasure and enjoyment, as well as eudaimonic aspects such as connections with nature, a sense of belonging, and personal achievement.

This research contributes to the existing body of knowledge on tourism engagement and tourist well-being in multifaceted ways. Firstly, this research study illuminates the multidimensionality of tourists’ engagement in experiences, linking behavioural, cognitive and emotional engagement with hedonic and eudaimonic well-being dimensions. This finding deepens our understanding of hybrid well-being models such as PERMA and DREAMA, demonstrating that their underlying dimensions are interconnected rather than completely independent. For instance, engagement in tourism experiences can lead to other well-being aspects, such as positive emotions, affiliation and achievement.

In tandem with the growing need for further research on travel engagement, there’s an increasing emphasis on ensuring that tourism experiences are accessible to everyone (Qiao et al., Citation2022). While previous studies have largely focused on the accessibility needs of those requiring moderate or high assistance, limited attention has been given to the mild access needs that all tourists may encounter (McKercher & Darcy, Citation2018). This research therefore advances our understanding of accessible tourism for all by considering the mild access needs of tourists within the framework of tourism engagement and well-being. Such a framework also opens opportunities for tourism services and facilities designed to accommodate diverse tourist groups.

Furthermore, despite the interplay between engagement and well-being being predominantly examined in different non-tourism contexts, such as education (Boulton et al., Citation2019), gerontology (Niedderer et al., Citation2022), and human resources management (Kim & Kim, Citation2021), this connection remains underexplored in the context of tourism (Rather, Citation2020). Consequently, this research contributes the Triple-A model, which articulates the multidimensional nature of engagement by emphasising how accessible facilities, available information, and accomplished service collectively enhance tourism engagement, with which tourists are more likely to receive greater well-being benefits.

This finding broadens existing conceptualisation of a key dimension of tourist well-being – engagement (Filep et al., Citation2024; Seligman, Citation2011), responding to calls for a deeper exploration of human well-being by specifically focusing on the often-neglected engagement dimension (Farkić et al., Citation2020). The Triple-A model also provides an integrated perspective that incorporates both the pull factors offered by tourism destinations and the constraints faced by tourists, which is critical for understanding how to promote tourist engagement effectively (Wen et al., Citation2020).

The Triple-A model offers a sound theoretical foundation for further empirical testing and validation, setting the stage for developing management strategies that enhance engagement in travel experiences and tourist well-being. For example, to enhance tourists’ perceived safety and engagement in activities, it is crucial to implement comprehensive safety insurance protocols and visibly display related certificates to reassure tourists. Secondly, tourism managers and service providers should be trained to recognise and respect the different self-construals of visitors. For independent tourists, it is essential to provide self-guided tools, solo traveller services, and easily accessible information to support autonomy and personal exploration. For interdependent tourists, offering interactive information services, group activities, and family-friendly amenities to foster connections would be more important. Additionally, tourism managers could conduct an arrival briefing at the destinations to help tourists become more familiar with the surroundings and alleviate their perceived uncertainty about the place. To create a hospitable environment that enhances tourists’ emotional engagement at a destination, it is vital to provide attentive service across all touchpoints. Training staff to be genuinely caring and responsive to tourist needs can make a significant difference. Organising welcoming and farewell events that integrate local culture and traditions can also enrich tourists’ emotional connections, fostering a sense of belonging and attachment to the place.

6. Conclusion

Tourist engagement is emerging as a crucial area for both academic research and industry practice (Michopoulou et al., Citation2015), driven not only by the critical need to promote human well-being and address a fundamental human rights concern, but in response to exceptional business opportunities (United Nations, Citation2016). This study critically identifies three pull factors in tourism destinations namely accessible facilities, available information, and accomplished service, and assesses their mechanisms for intrapersonal travel constraints negotiation and the enhancement of tourist engagement. Well-being outcomes derived from heightened tourist engagement are discussed drawing on empirical findings and literatures. The Triple-A model is developed to depict the dynamic relationship among pull factors for travel engagement, travel constraints negotiation and tourist well-being.

This research contributes to the existing body of knowledge on tourist well-being, engagement and the need for a more accessible and inclusive tourism industry. By focusing on the multidimensional engagement concept, this study offers timely insights for tourism providers and policies designed to empower a broader group of people to engage in tourism experiences (Eusébio et al., Citation2021). In particular, a notable investment should be placed in constructing accessible facilities in destinations, offering readily available information with respecting the diversity of visitors, and training employees to ensure the provision of accomplished service. For example, to negotiate the intrapersonal constraints of perceived unsafety from potential tourists, grants could be allocated to upgrade security equipment for risky activities and establish first aid facilities. This research also advances our understanding of tourist engagement beyond consumer marketing implications, towards psychological benefits of tourists themselves, which potentially broadens the tourism business market, and contributes to the achievement of SDGs, specifically SDG3 to improve the health and well-being of the global population (United Nations, Citation2015).

Several limitations exist in this study that should be addressed in future research. First, this research adopted a qualitative approach with a small sample size, future studies could adopt a quantitative approach, such as big data analysis, with a larger sample size to further examine the pull factors of engagement and tourist well-being. Second, future studies can further investigate the Triple-A model in a specific tourism context such as nature-based attractions and indigenous tourism experiences, enriching the visitor engagement management protocol from various tourism contexts. In addition, this study focuses on the pull factors for tourist engagement designed by destination managers, further investigation on how the host community influences tourist engagement in experiences could provide valuable insights. It would also be beneficial to explore the pull factors that drive residents’ engagement in tourism and the subsequent effects on their psychological well-being. With the increasing application of new technologies in tourism context (Bec et al., Citation2021), future studies are encouraged to explore how the employment of new technologies can assist individuals to negotiate perceived uncertainty and unsafety, thereby attracting and fostering meaningful visitor engagement. For example, pre-activity experience with virtual reality and mixed reality devices could be an efficient approach to alleviate potential tourists’ psychological and cognitive constraints related to certain tourism activities. Further research into inclusive tourism, combining the Triple-A model with new technology applications, could be particularly advantageous for individuals with access needs for tourism, such as the elderly or people with disabilities.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the Griffith University Research Ethics Committee in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. The GU reference number for this research is 2022/638.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alrawadieh, Z., Altinay, L., Cetin, G., & Şimşek, D. (2021). The interface between hospitality and tourism entrepreneurship, integration and well-being: A study of refugee entrepreneurs. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 97, 103013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103013

- Basu, M., Hashimoto, S., & Dasgupta, R. (2020). The mediating role of place attachment between nature connectedness and human well-being: Perspectives from Japan. Sustainability Science, 15(3), 849–862. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00765-x

- Bec, A., Moyle, B., Schaffer, V., & Timms, K. (2021). Virtual reality and mixed reality for second chance tourism. Tourism Management, 83, 104256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104256

- Bianchi, R. V., & de Man, F. (2021). Tourism, inclusive growth and decent work: A political economy critique. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(2-3), 353–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1730862

- Boulton, C. A., Hughes, E., Kent, C., Smith, J. R., & Williams, H. T. (2019). Student engagement and wellbeing over time at a higher education institution. PLoS One, 14(11), e0225770. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225770

- Boyle, C., Allen, K. A., Bleeze, R., Bozorg, B., & Sheridan, K. (2023). Enhancing positive wellbeing in schools: The relationship between inclusion and belonging. In M. A. White, F. McCallum, & C. Boyle (Eds.), New research and possibilities in wellbeing education (pp. 371–384). Singapore: Springer Nature.

- Brodie, R. J., Hollebeek, L. D., Jurić, B., & Ilić, A. (2011). Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. Journal of Service Research, 14(3), 252–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670511411703

- Buckley, R. C. (2019). Therapeutic mental health effects perceived by outdoor tourists: A large-scale, multi-decade, qualitative analysis. Annals of Tourism Research, 77(C), 164–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.12.017

- Buhalis, D., & Sinarta, Y. (2019). Real-time co-creation and nowness service: lessons from tourism and hospitality. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(5), 563–582. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1592059

- Burrows, D., & Kendall, S. (1997). Focus groups: What are they and how can they be used in nursing and health care research? Social Sciences in Health, 3, 244–253.

- Chang, L., Moyle, B. D., Dupre, K., Filep, S., & Vada, S. (2022). Progress in research on seniors’ well-being in tourism: A systematic review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 44, 101040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2022.101040

- Chang, L., Moyle, B. D., Vada, S., Filep, S., Dupre, K., & Liu, B. (2024). Re-thinking tourist wellbeing: An integrative model of affiliation with nature and social connections. International Journal of Tourism Research, 26(2), e2644. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2644

- Chathoth, P. K., Ungson, G. R., Altinay, L., Chan, E. S., Harrington, R., & Okumus, F. (2014). Barriers affecting organisational adoption of higher order customer engagement in tourism service interactions. Tourism Management, 42, 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.12.002

- Chaulagain, S., Pizam, A., & Wang, Y. (2021). An integrated behavioral model for medical tourism: An American perspective. Journal of Travel Research, 60(4), 761–778. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520907681

- Chen, C. C., Petrick, J. F., & Shahvali, M. (2016). Tourism experiences as a stress reliever: Examining the effects of tourism recovery experiences on life satisfaction. Journal of Travel Research, 55(2), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514546223

- Chen, H., & Rahman, I. (2018). Cultural tourism: An analysis of engagement, cultural contact, memorable tourism experience and destination loyalty. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 153–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.10.006

- Chen, S., Han, X., Bilgihan, A., & Okumus, F. (2021). Customer engagement research in hospitality and tourism: A systematic review. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(7), 871–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2021.1903644

- Choi, K. R., Heilemann, M. V., Fauer, A., & Mead, M. (2020). A second pandemic: Mental health spillover from the novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 26(4), 340–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078390320919803

- Cole, S., Zhang, Y., Wang, W., & Hu, C. M. (2019). The influence of accessibility and motivation on leisure travel participation of people with disabilities. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(1), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1496218

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Crawford, D. W., & Godbey, G. (1987). Reconceptualizing barriers to family leisure. Leisure Sciences, 9(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490408709512151

- Crawford, D. W., Jackson, E. L., & Godbey, G. (1991). A hierarchical model of leisure constraints. Leisure Sciences, 13(4), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409109513147

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2020). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Hachette UK.

- Dillette, A. K., Douglas, A. C., & Andrzejewski, C. (2019). Yoga tourism – a catalyst for transformation? Annals of Leisure Research, 22(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2018.1459195

- Eusébio, C., Teixeira, L., Moura, A., Kastenholz, E., & Carneiro, M. J. (2021). The relevance of internet as an information source on the accessible tourism market. In J. V. de Carvalho, Á. Rocha, P. Liberato, & A. Peña (Eds.), Advances in tourism, technology and systems. ICOTTS 2020. Smart innovation, systems and technologies (vol. 208, pp. 120–132). Singapore: Springer.

- Farkić, J., Filep, S., & Taylor, S. (2020). Shaping tourists’ wellbeing through guided slow adventures. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(12), 2064–2080. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1789156

- Figueiredo, E., Eusébio, C., & Kastenholz, E. (2012). How diverse are tourists with disabilities? A pilot study on accessible leisure tourism experiences in Portugal. International Journal of Tourism Research, 14(6), 531–550. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1913

- Filep, S., & Laing, J. (2019). Trends and directions in tourism and positive psychology. Journal of Travel Research, 58(3), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518759227

- Filep, S., Moyle, B. D., & Skavronskaya, L. (2024). Tourist wellbeing: Re-thinking hedonic and eudaimonic dimensions. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 48(1), 184 –193. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480221087964

- Flick, O. (2009). An introduction to qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367–1377. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1512

- Gardiner, S., Janowski, I., & Kwek, A. (2023). Self-identity and adventure tourism: Cross-country comparisons of youth consumers. Tourism Management Perspectives, 46, 101061. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2022.101061

- Gu, Q., & Huang, S. (2019). Profiling Chinese wine tourists by wine tourism constraints: A comparison of Chinese Australians and long-haul Chinese tourists in Australia. International Journal of Tourism Research, 21(2), 206–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2255

- Gu, Q., Qiu, H., King, B. E., & Huang, S. (2020). Understanding the wine tourism experience: The roles of facilitators, constraints, and involvement. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 26(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766719880253

- Gupta, S., Nath Mishra, O., & Kumar, S. (2023). Tourist participation, well-being and satisfaction: The mediating roles of service experience and tourist empowerment. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(16), 2613–2628. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2022.2091429

- Hao, F. (2020). The landscape of customer engagement in hospitality and tourism: A systematic review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(5), 1837–1860. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2019-0765

- Hapsari, R., Clemes, M. D., & Dean, D. (2017). The impact of service quality, customer engagement and selected marketing constructs on airline passenger loyalty. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 9(1), 21–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJQSS-07-2016-0048

- Harrigan, P., Evers, U., Miles, M., & Daly, T. (2017). Customer engagement with tourism social media brands. Tourism Management, 59, 597–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.09.015

- Heaton, J. (2022). “*pseudonyms Are used throughout”: A footnote, unpacked. Qualitative Inquiry, 28(1), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004211048379

- Heinonen, K. (2018). Positive and negative valence influencing consumer engagement. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 28(2), 147–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-02-2016-0020

- Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Weber, M. B. (2019). What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Qualitative Health Research, 29(10), 1483–1496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318821692

- Hollebeek, L. D., Glynn, M. S., & Brodie, R. J. (2014). Consumer brand engagement in social media: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 28(2), 149–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2013.12.002

- Hollebeek, L. D., Srivastava, R. K., & Chen, T. (2019). SD logic-informed customer engagement: Integrative framework, revised fundamental propositions, and application to CRM. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(1), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0494-5

- Huang, K., Pearce, P. L., Wu, M. Y., & Wang, X. Z. (2019). Tourists and Buddhist heritage sites: An integrative analysis of visitors’ experience and happiness through positive psychology constructs. Tourist Studies, 19(4), 549–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797619850107

- Huta, V. (2013). Pursuing eudaimonia versus hedonia: Distinctions, similarities and relationships. In A. S. Waterman (Ed.), The best within us: Positive psychology perspectives on eudaimonia (pp. 139–158). American Psychological Association.

- Kern, M. L., Williams, P., Spong, C., Colla, R., Sharma, K., Downie, A., Taylor, J. A., Sharp, S., Siokou, C., & Oades, L. G. (2020). Systems informed positive psychology. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(6), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799

- Khalil, R., Mansour, A. E., Fadda, W. A., Almisnid, K., Aldamegh, M., Al-Nafeesah, A., Alkhalifah, A., & Al-Wutayd, O. (2020). The sudden transition to synchronized online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study exploring medical students’ perspectives. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02208-z

- Kim, M., & Kim, J. (2021). Corporate social responsibility, employee engagement, well-being and the task performance of frontline employees. Management Decision, 59(8), 2040–2056. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-03-2020-0268

- Kim, Y. H., & Barber, N. A. (2022). Tourist’s destination image, place dimensions, and engagement: The Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and dark tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(17), 2751–2769. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1991896

- Krueger, R. A. (1994). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Sage Publications Inc.

- Krueger, R. A., & Casey, M. A. (2000). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research (4th ed.). Sage Publications Inc.

- Kumar, V., Rajan, B., Gupta, S., & Dalla Pozza, I. (2019). Customer engagement in service. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(1), 138–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0565-2

- Laing, J. H., & Frost, W. (2017). Journeys of well-being: Women's travel narratives of transformation and self-discovery in Italy. Tourism Management, 62, 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.04.004

- Lam, K. L., Chan, C. S., & Peters, M. (2020). Understanding technological contributions to accessible tourism from the perspective of destination design for visually impaired visitors in Hong Kong. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 17, 100434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2020.100434

- Lambert, L., Passmore, H. A., & Holder, M. D. (2015). Foundational frameworks of positive psychology: Mapping well-being orientations. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 56(3), 311. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000033

- Lee, S. M. F., Filep, S., Vada, S., & King, B. (2024). Webcam travel: A preliminary examination of psychological well-being. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 24(2), 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221145818

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2011). Beyond constant comparison qualitative data analysis: Using NVivo. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022711

- Liao, C., Zuo, Y., Xu, S., Law, R., & Zhang, M. (2023). Dimensions of the health benefits of wellness tourism: A review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1071578. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1071578

- Luan, J., Filieri, R., Xiao, J., Han, Q., Zhu, B., & Wang, T. (2023). Product information and green consumption: An integrated perspective of regulatory focus, self-construal, and temporal distance. Information & Management, 60(2), 103746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2022.103746

- McCabe, S., & Johnson, S. (2013). The happiness factor in tourism: Subjective well-being and social tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 42–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.001

- McKercher, B., & Darcy, S. (2018). Re-conceptualizing barriers to travel by people with disabilities. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26, 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.01.003

- Michopoulou, E., Darcy, S., Ambrose, I., & Buhalis, D. (2015). Accessible tourism futures: The world we dream to live in and the opportunities we hope to have. Journal of Tourism Futures, 1(3), 179–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-08-2015-0043

- Moses, J. F., Dwyer, P. C., Fuglestad, P., Kim, J., Maki, A., Snyder, M., & Terveen, L. (2018). Encouraging online engagement: The role of interdependent self-construal and social motives in fostering online participation. Personality and Individual Differences, 133, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.035

- Neal, J. D., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2007). The effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 154–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507303977

- Newman, D., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective wellbeing: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9435-x

- Niedderer, K., Holthoff-Detto, V., Van Rompay, T. J., Karahanoğlu, A., Ludden, G. D., Almeida, R., Durán, R. L., Aguado, Y. B., Lim, J. N.W., Smith, T., Harrison, D., Craven, M. P., Gosling, J., Orton, L., & Tournier, I. (2022). This is Me: Evaluation of a boardgame to promote social engagement, wellbeing and agency in people with dementia through mindful life-storytelling. Journal of Aging Studies, 60, 100995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2021.100995

- Nyaupane, G. P., & Andereck, K. L. (2008). Understanding travel constraints: Application and extension of a leisure constraints model. Journal of Travel Research, 46(4), 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507308325

- O. Nyumba, T., Wilson, K., Derrick, C. J., & Mukherjee, N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conservation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12860

- Palaganas, E. C., Sanchez, M. C., Molintas, V. P., & Caricativo, R. D. (2017). Reflexivity in qualitative research: A journey of learning. Qualitative Report, 22(2), 426–438.

- Patterson, I., & Balderas, A. (2020). Continuing and emerging trends of senior tourism: A review of the literature. Journal of Population Ageing, 13(3), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12062-018-9228-4

- Peker, M., Booth, R. W., & Eke, A. (2018). Relationships among self-construal, gender, social dominance orientation, and interpersonal distance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 48(9), 494–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12529

- Prentice, C., Han, X. Y., Hua, L.-L., & Hu, L. (2019). The influence of identity-driven customer engagement on purchase intention. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 339–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.12.014

- Qiao, G., Ding, L., Zhang, L., & Yan, H. (2022). Accessible tourism: A bibliometric review (2008–2020). Tourism Review, 77(3), 713–730.

- Rabiee, F. (2004). Focus-group interview and data analysis. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 63(4), 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS2004399

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Khoo-Lattimore, C., Md Noor, S., Jaafar, M., & Konar, R. (2021). Tourist engagement and loyalty: Gender matters? Current Issues in Tourism, 24(6), 871–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1765321

- Rather, R. A. (2020). Customer experience and engagement in tourism destinations: The experiential marketing perspective. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 37(1), 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1686101

- Rather, R. A., Hollebeek, L. D., & Islam, J. U. (2019). Tourism-based customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. The Service Industries Journal, 39(7-8), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2019.1570154

- Rátz, T., & Michalkó, G. (2011). The contribution of tourism to well-being and welfare: The case of Hungary. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 14(3-4), 332–346. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSD.2011.041968

- ReportLinker. (2023, February 28). Wellness tourism market size, share & trends analysis report by service, by travel purpose, by travel type, by region and segment forecasts, 2023—2030. Globe Newswire. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/wellness-tourism-market

- Riley, T., & White, V. (2016). Developing a sense of belonging through engagement with like-minded peers: A matter of equity. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 51(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-016-0065-9

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster.

- Shin, H., Nicolau, J. L., Kang, J., Sharma, A., & Lee, H. (2022). Travel decision determinants during and after COVID-19: The role of tourist trust, travel constraints, and attitudinal factors. Tourism Management, 88, 104428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104428

- Sim, M., & Plewa, C. (2017). Customer engagement with a service provider and context: An empirical examination. Journal of Service Theory and Practice, 27(4), 854–876. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTP-03-2016-0057

- Sirgy M. J. (2019). Promoting quality-of-life and well-being research in hospitality and tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2018.1526757

- Sirgy, M. J., & Uysal, M. (2016). Developing a eudaimonia research agenda in travel and tourism. In J. Vittersø (Ed.), Handbook of eudaimonic well-being (pp. 485–495). Springer.

- Sirgy, M. J., Uysal, M., & Kruger, S. (2017). Towards a benefits theory of leisure well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 12(1), 205–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-016-9482-7

- Sisto, R., Cappelletti, G. M., Bianchi, P., & Sica, E. (2022). Sustainable and accessible tourism in natural areas: A participatory approach. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(8), 1307–1324. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1920002

- Smith, M. K., & Diekmann, A. (2017). Tourism and wellbeing. Annals of Tourism Research, 66, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.05.006

- So, K. K. F., King, C., & Sparks, B. (2014). Customer engagement with tourism brands: Scale development and validation. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 38(3), 304–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348012451456

- So, K. K. F., King, C., Sparks, B. A., & Wang, Y. (2016). The role of customer engagement in building consumer loyalty to tourism brands. Journal of Travel Research, 55(1), 64–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287514541008

- So, K. K. F., Li, X., & Kim, H. (2020). A decade of customer engagement research in hospitality and tourism: A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 44(2), 178–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348019895562

- Steptoe, A., Deaton, A., & Stone, A. A. (2015). Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. The Lancet, 385(9968), 640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0

- Strauss, A. (1998). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge University Press.

- Su, L., Yang, X., & Huang, Y. (2022). How do tourism goal disclosure motivations drive Chinese tourists’ goal-directed behaviors? The influences of feedback valence, affective rumination, and emotional engagement. Tourism Management, 90, 104483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104483

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication

- United Nations. (2016). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities

- Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., & Kim, H. (2016). Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tourism Management, 53, 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

- Vada, S., Filep, S., Moyle, B., Gardiner, S., & Tuguinay, J. (2023). Welcome back: Repeat visitation and tourist wellbeing. Tourism Management, 98, 104747. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104747

- Vada, S., Prentice, C., Filep, S., & King, B. (2022). The influence of travel companionships on memorable tourism experiences, well-being, and behavioural intentions. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(5), 714–724. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2533

- Vada, S., Prentice, C., Hsiao, A. (2019). The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 47, 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.12.007

- Vada, S., Prentice, C., Scott, N., & Hsiao, A. (2020). Positive psychology and tourist well-being: A systematic literature review. Tourism Management Perspectives, 33, 100631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100631

- Verhoef, P. C., Reinartz, W. J., & Krafft, M. (2010). Customer engagement as a new perspective in customer management. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375461

- Wan, Y. K. P., Lo, W. S. S., & Eddy-U, M. E. (2022). Perceived constraints and negotiation strategies by elderly tourists when visiting heritage sites. Leisure Studies, 41(5), 703–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2022.2066710

- Wen, J., Huang, S. S., & Goh, E. (2020). Effects of perceived constraints and negotiation on learned helplessness: A study of Chinese senior outbound tourists. Tourism Management, 78, 104059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104059

- Wesson, K., & Boniwell, I. (2007). Flow theory – its application to coaching psychology. International Coaching Psychology Review, 2(1), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsicpr.2007.2.1.33

- Williams, G. M., Tapsell, L. C., & Beck, E. J. (2023). Gut health, the microbiome and dietary choices: An exploration of consumer perspectives. Nutrition & Dietetics, 80(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/1747-0080.12769

- Williams, M., & Moser, T. (2019). The art of coding and thematic exploration in qualitative research. International Management Review, 15(1), 45–55.

- Williamson, J., Hassanli, N., & Grabowski, S. (2022). OzNomads: A case study examining the challenges of COVID-19 for a community of lifestyle travellers. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(2), 232–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1928009

- Yiamjanya, S., & Wongleedee, K. (2014). International tourists’ travel motivation by push-pull factors and the decision making for selecting Thailand as destination choice. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 8(5), 1348–1353.

- Zhang, H., Yang, Y., Zheng, C., & Zhang, J. (2016). Too dark to revisit? The role of past experiences and intrapersonal constraints. Tourism Management, 54, 452–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.01.002

- Zhou, P. P., Wu, M. Y., Filep, S., & Weber, K. (2021). Exploring well-being outcomes at an iconic Chinese LGBT event: A PERMA model perspective. Tourism Management Perspectives, 40, 100905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100905

- Zyoud, S. H. (2023). Analyzing and visualizing global research trends on COVID-19 linked to sustainable development goals. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(6), 5459–5493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02275-w