ABSTRACT

This study investigated the effects of accessible work-family policies (WFP) and organisational support on job satisfaction mediated by employee well-being. Furthermore, it examined whether these relationships differed depending on employees’ gender and family responsibilities. The study involved 568 participants employed in the Spanish tourism industry, including front-line workers and managerial staff, with a similar proportion of male and female employees, nearly half of whom had family responsibilities. The valid questionnaires were analyzed using the PLS-SEM technique. The results highlighted the importance of organisational support and the accessibility of WFP in determining satisfaction in the workplace. While WFP accessibility had a residual effect, organisational support had a more substantial impact on overall satisfaction. Moreover, emotional and physical well-being (EWB, PWB) were crucial factors that directly influenced job satisfaction and mediated the relationship. The study revealed that family responsibilities and gender significantly shaped the relationships between organisational support, WFP accessibility, EWB, and PWB.

Introduction

Tourism is one of the most widespread industries worldwide and considerably influences the economy, society, and the environment. However, the importance of the tourism industry contrasts with the fact that employees in this sector often experience conflicts when trying to reconcile work and family life, and it is crucial to find a balance between the two (Tepavčević, Blešić, et al., Citation2021) and to take into account the well-being of workers in this sector. Therefore, managers of tourism companies, such as those in the hotel sector, should consider work-family conflict (WFC) and take measures to reduce it (Zhao, Ghiselli, et al., Citation2020), given its impact on the subjective well-being of employees in this sector (Yang & Jo, Citation2022).

The concept of WFC and the implementation of work-family policies (WFP) progressively garnered the interest of researchers (Anand & Vohra, Citation2021; Arefin et al., Citation2020; Bettac & Probst, Citation2023; Vadvilavičius & Stelmokienė, Citation2020). It was shown that managers’ policies favourable to work-family balance and supervisor support negatively affected WFC (Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023). In this sense, promoting WFP was essential to overcome WFC and increase well-being and job satisfaction (Isfianadewi & Noordyani, Citation2020; Kashyap & Kaur, Citation2021). The need to analyze the impact of WFP on well-being and job satisfaction was due to the fact that the tourism sector presented obstacles for balancing work responsibilities with family responsibilities, due to the characteristics of work organisation and structural issues. Among these obstacles was a highly variable demand cycle, with irregular work schedules, part-time employment, and unpredictable work shifts (ILO, Citation2017). Additionally, industries with high levels of informal work, common in tourism, often reduced job security and limited access to social protection, which affected workers’ well-being and satisfaction (El Achkar, Citation2023). For this reason, increasingly more organisations implemented WFP due to the beneficial effects for workers and organisations (Lyonette & Baldauf, Citation2019). However, the simple implementation of WFP was insufficient to overcome WFC. In addition, employees should have accessed WFP without reprisal or any other negative consequences (Medina-Garrido, Biedma-Ferrer, and Rodríguez-Cornejo, Citation2021). In this regard, the literature showed some gaps when studying the impact of WFP on job satisfaction. On the one hand, research on the influence of WFP on job satisfaction did not differentiate between the existence of these policies and their actual accessibility for workers (Medina-Garrido, Biedma-Ferrer, and Ramos-Rodríguez, Citation2021). Moreover, these studies often did not investigate the extent to which these policies received strong support within the organisation (Burke, Citation2010). On the other hand, there were no studies on how this organisational support and accessibility to WFP impacted satisfaction regarding the mediating role of the well-being that this support and these policies could generate in employees (Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023).

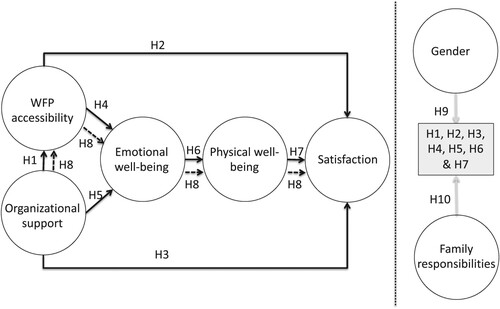

To address the research gaps identified earlier, this study investigated the influence of accessibility of WFP and organisational support on employee satisfaction, directly and indirectly, by considering the well-being these WFP and support generated. Additionally, the analysis examined whether these relationships were contingent upon employees’ family responsibilities and gender. To accomplish this objective, the following section outlined several hypotheses that established connections between organisational support, WFP accessibility, and job satisfaction, with emotional and physical well-being (EWB, PWB) as sequential mediators. A dataset comprising 568 valid questionnaires was gathered from individuals employed in the Spanish tourism sector to test these hypotheses. Subsequently, the data underwent analysis through a structural equation model employing the PLS-SEM approach.

The findings of this study provide practical contributions to the management of tourism companies. In this regard, it is suggested that management adopt a holistic approach that considers how work-family balance and organisational support can improve employee well-being and satisfaction, benefiting both workers and organisations. This knowledge would allow the design of policies, guidelines, and training courses that guide management in making WFP accessible within a supportive organisational culture. This is especially relevant in many positions within the tourism sector, where job demands make such balance difficult and are a potential source of conflict between work and family. Additionally, company management should ensure their employees’ emotional well-being and the work-family balance measures implemented should be tailored to each worker’s specific needs based on their gender and family responsibilities.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Organisational support is the degree to which an organisation values and cares for its employees in various dimensions, including equipment, materials, information, new technologies, financial resources, new ideas, and physical and emotional assistance (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017). The literature has highlighted that managing the relationships between managers and employees in the tourism industry requires a deep understanding of the specific needs and expectations of employees in this sector, as well as efforts to create an inclusive, equitable, and supportive work environment (Faddila & Senen, Citation2023). The academic literature has pointed to the importance of organisational support in improving working conditions and employee well-being (Arslaner & Boylu, Citation2017). Moreover, Claudia (Citation2018) found that organisational support significantly improved job satisfaction in the educational sector. Additionally, Yadav and Sharma (Citation2023) observed that workers perceived organisational support positively in the services sector, which helped reduce WFC. Iqbal et al. (Citation2022) highlighted that organisational support significantly impacted employees’ work-life balance in the educational sector. Supervisors had a crucial role to play in reducing WFC (Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023), and it was essential that they provided support to their employees at all levels to facilitate access to WFP. However, employees should perceive that access to these policies would not generate social or professional retaliation (Medina-Garrido et al., Citation2020). Based on these arguments concerning different sectors, and by analogy in the tourism sector, we can define our first hypothesis:

H1. Organizational support is positively related to WFP accessibility.

Costantini et al. (Citation2021) conceptualised WFP as a job resource, and their study findings showed that the availability of policies was either directly or indirectly positively related to work attitudes. Bourdeau et al. (Citation2018) highlighted the importance of managers, especially their interpretation of the WFP used, which might have resulted in positive and negative career consequences for employees. In this regard, and since issues related to WFC have received less attention in the tourism sector, the reviewed literature was inconclusive, demanding the need for further research on WFP in this sector (Kim et al., Citation2023). Lee and Kramer (Citation2022) proposed a new construct, ‘psychological accessibility’, since not all employees embraced the benefits of WFP because they experienced a fear of using such policies. Psychological accessibility could moderate the relationship between employees’ family needs and the utilisation of WFP (Lee & Kramer, Citation2022). Therefore, it is not enough that WFP exist in the organisation. Hence these policies must also be accessible without subsequent reprisals for workers who use them (Medina-Garrido et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). Increased accessibility to WFP is crucial for enhancing employee job satisfaction (Debnath, Citation2023; Memili et al., Citation2023). Based on these findings, our second hypothesis is:

H2. WFP accessibility is positively related to satisfaction.

H3. Organizational support is positively related to satisfaction.

H4. WFP accessibility is positively related to EWB.

H5. Organizational support is positively related to EWB.

H6. EWB is positively related to PWB.

H7. PWB is positively related to job satisfaction.

H8. WFP accessibility, EWB, and PWB sequentially mediate the relationship between organizational support and job satisfaction.

H9. The gender of the worker moderates the model’s relationships.

H10. Worker family responsibilities moderate the model’s relationships.

Methodology

Survey procedure and sampling method

The study was conducted across Spain and included any industry within the tourism sector. The study encompassed 568 valid surveys, with 45.1% from females, 54.9% from males, and 73.8% reporting family responsibilities among the respondents. The survey was designed and administered online using Google Forms. Participants were contacted through representatives of associations to which the employees belonged. To avoid work-related issues, participants were invited to forward the email to their personal email addresses and complete the survey outside of work hours and premises. Ethical considerations were also addressed by obtaining informed consent from all participants and ensuring the confidentiality of their responses. The estimated time to complete the survey was 15 minutes.

Figure 1. Theoretical model.

Note: H8, a mediation hypothesis with indirect effects, is represented with a dashed line to differentiate it from direct effects. For simplification and visual clarity, the moderation hypotheses are represented separately. These affect all relationships in the model.

To explore the potential moderating impact of the variables gender and family responsibilities, we partitioned the sample into four distinct subsamples. To study this effect, we created a categorical variable based on permutation analysis, which is the most reliable and recommended test for this analysis (Chin, Citation2003). The subsamples we generated were: (1) men without family responsibilities, (2) men with family responsibilities, (3) women without family responsibilities, and (4) women with family responsibilities. With a statistical power of 0.8 and a standard alpha level of 0.05, our sample size of 568 enables us to detect even very small effect sizes, which are typically more challenging to discern, as Cohen’s (Citation1988) guidelines. The sample size associated with each group is 94, 218, 55, and 201 observations, respectively.

Measures

Due to correlations among indicators within each variable, we employed composites in Mode A and utilised correlation weights (Henseler, Citation2017). The indicators for all variables were multiple and based on the assessment of statements with a Likert scale of 7, except for the moderating variables of gender and family responsibilities. We measured the WFP Accessibility with 15 items from the scales of Anderson et al. (Citation2002) and Families and Work Institute (Citation2012b, Citation2012a). Sample items include: ‘The application procedures are simple’ and ‘I have the flexible working hours I need at work to manage my personal and family responsibilities’. We measured the Organisational Support variable with a 7-item scale from the Families and Work Institute measurement scale (Citation2012b). Sample items include: ‘My supervisor or manager is fair and doesn’t show favoritism in responding to employees’ personal or family needs’ and ‘I have support from coworkers that helps me to manage my work and personal or family lives’. The EWB variable was composed of 15 items, based on the scales of Warr (Citation1990) and Kossek et al. (Citation2001). Sample items include: ‘In relation to the well-being or discomfort you feel at work, during the last few weeks, how many times has your work made you feel?: Calm’ and ‘(…) Depressed’. PWB, composed of 9 items based on the Kossek et al. (Citation2001) scale, considered somatic reactions felt in the previous weeks by individuals caused by their work concerns. Sample items include: ‘In relation to the well-being or discomfort you feel at work, during the last few weeks, how many times has your work made you feel?: Annoying trembling of my hands’ and ‘(…) Problems with sleeping at night’. The Satisfaction variable was measured with 14 indicators taken from various scales validated by the previous literature (Anderson et al., Citation2002; Caplan et al., Citation1975; Carlson et al., Citation2000; Judge et al., Citation2003). Sample items include: ‘The work I do on my job is meaningful to me’ and ‘All in all, I am satisfied with my job’. As for the moderating variables, we used two categorical variables referring to gender and family responsibilities. The existence of family responsibilities is considered if individuals without partners or with working partners have children under the age of 18 or have disabled or elderly dependents in their care. Appendix I contains, at the end of this paper, all the measurement scale items for the variables of the model.

Method

We applied structural equation modeling using PLS-SEM methodology to test the proposed hypotheses. We ensured consistent estimates and followed the methodological recommendations of Hair et al. (Citation2014) since the variables were modeled as composites. Before the analysis, we assessed this study’s potential impact of common method bias. Following Koc’s (Citation2015) recommendations, we conducted the full collinearity test based on variance inflation factors (VIFs) to investigate this potential issue. The test establishes that a VIF value exceeding 3.3 would suggest the presence of common method bias in the model. In our study, the highest VIF value observed is 1.814, indicating the absence of this bias in the model.

Results

Evaluation of the global model

In our study, we conducted two assessments of the global model: one considering all the indicators before analyzing the measurement model and another after eliminating the indicators that did not meet the reliability and validity requirements. To analyze the global model, we used approximate fit measures (Henseler, Hubona, et al., Citation2016), such as the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), whose threshold was set at 0.08 in the study by Hu and Bentler (Citation1998) or, in a more flexible option proposed by Ringle et al. (Citation2015), below 0.1. The results indicated values of 0.085 before the removal of indicators and 0.082 following the removal of these indicators. These findings suggest that the model exhibits improved fit after removing problematic indicators. In short, the model has an acceptable fit using the more flexible Ringle et al.

Other model adjustment measures that support the obtained result include the normalised fit index (NFI), with a value of 0.906 in the model, which indicates an acceptable fit since it is above 0.9. Additionally, the root mean square residual covariance matrix of the external model (RMS theta) has a value of 0.107 in our study, which is below the threshold of 0.12, indicating a good fit.

Assessment of the measurement model

We evaluated the individual reliability of each item by examining the factor loadings relative to their respective constructs. We considered the threshold recommended by Carmines and Zeller (Citation1979), indicating that indicators with factor loadings exceeding 0.707 are considered valid. However, it’s noteworthy that some scholars argue that indicators with factor loadings within the range of 0.4–0.707 need not be removed unless they pose issues to the measurement model. In this study, three indicators corresponding to the ‘Accessibility’ variable with very low loads (below 0.4) were eliminated. Additionally, two indicators from the ‘Accessibility’ variable, one from the ‘Organizational Support’ variable, and four from the ‘Satisfaction’ variable were removed to adhere to convergent validity requirements, thus enhancing the average variance extracted (AVE). The final Appendix of this paper shows the measurement scale items that were removed. Secondly, we examined construct reliability to determine the similarity in scores of items measuring a construct. The composite reliability measure proposed by Werts et al. (Citation1974) and Dijkstra and Henseler (Citation2015) was used, with values above 0.8 considered suitable for advanced stages of research according to Nunnally and Bernstein (Citation1994). Following that, we conducted a test for convergent validity to confirm that the indicators collectively represent a unified underlying construct. We utilised the AVE measure, setting a minimum acceptable value at 0.5, which is in line with the recommendation of Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). Finally, we assessed discriminant validity, gauging the extent to which a specific construct differs from others, using the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) as recommended by Henseler, Ringle, et al. (Citation2016). Alternatively, the criterion of Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) can also be used via the matrix of correlations between variables. Once the aforementioned indicators have been eliminated, the model meets the requirements of construct reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. includes a summary of the results of the measurement model evaluation.

Table 1. Assessment of the measurement model.

Structural model

After confirming our model’s reliability and validity, we investigated the seven hypotheses embedded within the model by employing the bootstrapping resampling method, which involved 5,000 samples. Using this methodology, we evaluated the magnitude, direction, and statistical significance of the relationships between variables. Moreover, we measured the model’s predictive capacity by examining the coefficient of determination (R²) for endogenous variables (Chin, Citation1998). Later, we decomposed the explained variance to understand the importance of each antecedent variable in the dependent variable. Finally, we used rules of Cohen (Citation1988) to assess the size of the effects. The results of the analysis are reflected in .

Table 2. Structural model. Direct effects.

The R² values obtained in this model indicate that the predictive power for the dependent variables of Accessibility and EWB is relatively low, while it is moderate for the variables of PWB and Satisfaction. All seven of our hypotheses are supported, although they exhibit varying degrees of effects. Specifically, H2 is confirmed with a residual effect, H4 and H5 with small effects, H1, H3, and H7 with moderate effects, and H6 with a large effect, which aligns with Cohen’s (Citation1988) guidelines. Furthermore, when examining potential mediating effects within the model to validate H8, we discovered that WFP Accessibility, EWB, and PWB mediate all conceivable relationships within the theoretical model ().

Table 3. Structural model. Indirect effects (Mediation).

Moderating role of gender and family responsibilities

Ultimately, a multigroup analysis was conducted to explore the moderating effect of the variable associated with individuals’ family responsibilities and gender to validate hypotheses H9 and H10. The sample was divided into four subsamples: (1) men without family responsibilities, (2) men with family responsibilities, (3) women without family responsibilities, and (4) women with family responsibilities. Analysis of the models for these groups revealed certain distinctions. To assess their significance, we employed a multigroup analysis based on permutations (Chin, Citation2003).

In the initial step, we examined measure invariance to confirm that differences between groups could be attributed to path coefficients rather than parameters of the measurement model. The preliminary analysis indicated total or partial invariance in all cases, except for the variable Accessibility in the comparison between Men without responsibilities and Women without responsibilities, for the variable PWB in the comparisons between Men with responsibilities and Women without responsibilities, and between Women without responsibilities and Women with family responsibilities. Following the permutation analysis (Chin, Citation2003), significant differences were identified in the following comparisons: (1) between men with and without family responsibilities regarding the relationship between EWB and PWB, with a greater impact on the relationship when they had family responsibilities; (2) between men and women without family responsibilities in the relationships between Organisational Support and EWB, as well as between EWB and PWB, with a greater impact of the female gender on both relationships; (3) between men with responsibilities and women without family responsibilities in the relationships between Accessibility and EWB, with a greater impact of men, and between Organisational Support and EWB, for which women have a greater impact; and (4) between men and women with family responsibilities concerning the relationship between Accessibility and EWB, with a stronger moderating effect in the case of men.

Discussion

The main objective of this work is to address some gaps in the literature on work-family balance and its impact on workers. In this regard, we have focused on the impact of organisational support for workers and their actual accessibility to their organisation’s WFP on job satisfaction (Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023), examining the mediating role of well-being in these relationships (Medina-Garrido, Biedma-Ferrer, & Ramos-Rodríguez, Citation2021). Additionally, this work also analyzes how gender and family responsibilities moderate these relationships, responding to the demand for more detailed studies that include the impact of these variables in the area of work-family balance (Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023). Moreover, it is relevant to highlight that this analysis is carried out in the tourism industry in Spain, a sector known for its high stress levels and work-family conflict (Tepavčević, Vukosav, et al., Citation2021; Zhao, Ghiselli, et al., Citation2020). Previous studies do not show conclusive results and call for more research on WFP in this sector (Kim et al., Citation2023). The tourism industry requires a deep understanding of the needs and expectations of employees, as well as efforts to create an equitable and supportive work environment (Faddila & Senen, Citation2023). Additionally, research has evidenced the importance of tourism organisations continuously monitoring their staff’s satisfaction and taking measures to improve it (Bednarska, Citation2015).

As a result of the study’s objective, the tested theoretical model offers a holistic view of the impact of WFP and organisational support on employee satisfaction. In line with the proposed model, the findings of this study indicate that merely implementing WFP is not sufficient; the accessibility of these policies and the support provided play crucial roles in generating well-being and, both directly and indirectly, in employee job satisfaction. Organisational support emerges as a central factor that directly influences job satisfaction but also has a significant indirect effect by enhancing the accessibility of WFP and, in turn, employees’ emotional well-being. This interaction highlights the synergy between work-family balance policies and a supportive culture. Furthermore, the moderating influence of gender and family responsibilities reveals significant disparities in how organisational support and access to WFP affect the mentioned well-being, suggesting the need for personalised approaches and further studies on these differences. The results of this study are described in greater detail below.

From our results, it is clear that accessibility to WFP has a positive impact on satisfaction, although its effect is residual. However, organisational support is even more important than WFP accessibility in increasing employee satisfaction. Organisational support improves employee job satisfaction, both directly and indirectly, by mediating the accessibility of WFP and the well-being that this support and WFP generate. These results are consistent with previous studies confirming the importance of organisational support for employee satisfaction (Crucke et al., Citation2022; Ganji et al., Citation2021; Mascarenhas et al., Citation2022; Zeng et al., Citation2020) and the mediating effect of well-being between accessibility to WFP and key organisational variables (Medina-Garrido et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). According to the previous literature, organisational support increases job satisfaction because workers positively value this support, and it has a synergistic effect with WFP in reducing employees’ WFC (Iqbal et al., Citation2022; Maszura & Novliadi, Citation2020; Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023). However, our results contrast with those of Zhao, Wang, et al. (Citation2020), whose results showed that organisational support reduces tourism employees’ WFC and improves their life satisfaction, but not their job satisfaction. In this regard, our work enriches the scarce literature on this subject in the tourism sector.

Furthermore, this study contributes to previous work highlighting the importance of organisational support on employee well-being (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017; Roemer & Harris, Citation2018). However, to our knowledge, no previous research has analyzed the positive impact, investigated in the present study, of accessibility to WFP on workers’ EWB, either directly or through its role as a mediator in the relationship between organisational support and EWB.

On the other hand, consistent with the literature, our findings provide evidence that EWB and PWB are positively and strongly connected (Acosta-González & Marcenaro-Gutiérrez, Citation2021; Brunner et al., Citation2019) and essential for job satisfaction (Semlali & Hassi, Citation2016). In this regard, managers in the tourism sector should be aware of the importance of caring for employees and take appropriate measures to take care of their mental health and PWB (Xiong et al., Citation2023).

Concerning the moderating influence of gender and family responsibilities, notable disparities were observed in how organisational support and access to WFP affected EWB and the connection between EWB and PWB. More specifically, there are significant differences between men with and without family responsibilities in the EWB and PWB relationship. When comparing men and women without family responsibilities, significant differences were observed in the relationship between organisational support and EWB and between EWB and PWB. For men with responsibilities and women without family responsibilities, there are significant differences in the relationship between WFP accessibility and EWB and between organisational support and EWB. Finally, there are significant differences between men and women with family responsibilities in the relationship between WFP accessibility and EWB. These results are consistent with previous studies analyzing the variable family responsibilities, in which the importance of job well-being is evident, as caring for family members can often be a source of stress (DePasquale et al., Citation2017; Stewart et al., Citation2022). However, the previous literature on the moderating role of gender shows contradictory results and calls for further studies (Medina-Garrido, Biedma-Ferrer, & Ramos-Rodríguez, Citation2021; Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023). In this sense, the findings of our work on the gender variable provide additional evidence to the literature on its moderating role.

Theoretical implications for the literature

Regarding the implications of this study for the literature, we have addressed some gaps in the literature on the impact of WFP accessibility and organisational support on job satisfaction. This approach is particularly important, given that some studies confuse the mere existence of WFP, often imposed by government regulation, with the worker’s actual possibility of enjoying such measures without retaliation (Medina-Garrido et al., Citation2017, Citation2020). However, in this paper, we also analyzed the critical role of organisational support as an independent factor that enhances job satisfaction and as a facilitator that increases accessibility to WFP (Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023). There is little study on this relationship in the literature, despite previous studies indicating that supervisors play a crucial role in reducing WFC (Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023). Moreover, while the previous literature has studied the impact of WFP and organisational support on job satisfaction separately (Medina-Garrido et al., Citation2017, Citation2020), our study further demonstrates the synergistic impact of these two variables on job satisfaction in the same model.

The reasons behind these findings can be diverse. The unique nature of work in the tourism industry, with irregular hours and high job demands, can amplify both the impact of WFP and the importance of organisational support. This specific context could explain why organisational support has a stronger effect on job satisfaction than studies in other sectors (Tepavčević, Vukosav, et al., Citation2021; Zhao, Ghiselli, et al., Citation2020). It is also important to consider employees’ perceptions of the accessibility to WFP and organisational support, which can vary significantly depending on corporate cultures. In organisations where employees perceive that using WFP does not have negative repercussions, these policies are more likely to positively impact their well-being and satisfaction (Medina-Garrido et al., Citation2020).

On the other hand, it is demonstrated that well-being is a desired outcome and a critical mediator that connects organisational policies with job satisfaction (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017; Roemer & Harris, Citation2018). Our findings confirm the strong connection between EWB and PWB. While this connection is present in the previous literature (Acosta-González & Marcenaro-Gutiérrez, Citation2021; Brunner et al., Citation2019), our work analyzes this relationship within the specific domain of work-life balance in the tourism sector. Additionally, the analysis of gender differences and family responsibilities as moderators of these relationships offers new perspectives on how these factors can influence work-family conflict and balance, responding to the demand for more detailed studies on these differences (Medina-Garrido, Biedma-Ferrer, & Ramos-Rodríguez, Citation2021; Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023). This implies the need to develop personalised approaches to implement work-life balance and support policies.

Practical implications

The findings of this study have important practical implications. As noted, the accessibility of WFP has a positive effect on job satisfaction. Organisations in the tourism industry, as well as in other sectors, can benefit by recognising that it is not only crucial to have work-family policies but also to ensure that employees feel comfortable using them without fear of repercussions (Medina-Garrido et al., Citation2020). For this reason, organisations should regularly evaluate the accessibility of their WFP. Anonymous surveys and focus groups can be useful in identifying perceived barriers by employees and adjusting policies according to the workforce’s specific needs. This proactive approach can help ensure that policies not only exist on paper but are also effectively utilised by employees freely (Medina-Garrido, Biedma-Ferrer, & Ramos-Rodríguez, Citation2021).

However, the effect of WFP on satisfaction is residual compared to that of organisational support. This suggests that while WFP are important, their effectiveness largely depends on the organisational support context in which they are implemented (Medina-Garrido et al., Citation2023). Organisational support emerges as a critical factor for job satisfaction, directly and through its influence on the accessibility of WFP and employee well-being. This finding underscores the need for organisations to promote a culture that actively values and supports employees among their managers and leaders (Yadav & Sharma, Citation2023). In any case, work-family balance needs can vary among employees, so it would be beneficial for organisations to offer options that best suit the personal and family circumstances of their employees. Undoubtedly, this flexibility can increase the perception of organisational support and improve job satisfaction (Bourdeau et al., Citation2018).

Moreover, this study confirms that emotional and physical well-being are key mediators in the relationship between organisational support, the accessibility of WFP, and job satisfaction. This implies that initiatives that generally enhance employee well-being can also have amplified positive effects on job satisfaction (Kurtessis et al., Citation2017; Roemer & Harris, Citation2018). Therefore, human resources management should focus on support and work-family policies and on developing an environment that promotes overall employee well-being (Gordon et al., Citation2019). A practical recommendation is that managers should be aware of the strong impact of EWB on PWB, striving to create and develop an organisational culture of emotional support for workers. In this regard, it is essential that managers receive training in empathetic leadership skills and well-being management, equipping them to offer emotional support and enhance the accessibility of WFP, fostering a more family-friendly work environment (Dalgaard et al., Citation2023). Additionally, initiatives such as stress management workshops, physical activities at the workplace, and employee assistance programs can contribute to a more satisfying work environment (Grzywacz & Marks, Citation2000).

Finally, the observed differences in how gender and family responsibilities moderate these relationships highlight the need for personalised approaches in policy implementation. Organisations should consider these differences to design inclusive and suitable policies for all employees (DePasquale et al., Citation2017; Stewart et al., Citation2022).

Limitation

One limitation of this study is that in analyzing the moderating variables of gender and family responsibilities, we cannot state that a model relationship is higher or lower for one group or the other. We can only state that there are significant differences in the model relationships and that these relationships work differently for the compared groups. Another limitation is the contextual factors. Since this study is performed in Spain, cultural norms, laws, and regulations might influence the results. In addition, the sample analyzed belongs to the tourism sector, and although this adds value to the literature on this sector, it also means that the results could differ from those of other sectors.

Future research

However, the limitations mentioned above can be ideas for future studies. Considering that the sample was drawn from the Spanish tourism sector, it would be valuable to duplicate this research in alternative sectors and nations characterised by diverse cultures, labour regulations, and levels of economic advancement. This approach aims to enhance the applicability and broader relevance of the findings. It could also be interesting to repeat the study over several years for a longitudinal analysis. Finally, the differences in the level of well-being between men and women, with or without family responsibilities, maybe a topic for further development.

Conclusion

Despite its significant impact on the economy, society, and the environment, the tourism industry faces considerable challenges regarding worker well-being and job satisfaction due to the specific characteristics of jobs in this sector (Montañés-Del-Río & Medina-Garrido, Citation2020). This study addresses these challenges by investigating how organisational support and the accessibility of work-family balance policies (WFP) influence employee job satisfaction, considering that this influence is also mediated by emotional and physical well-being. The results indicate that while the accessibility of WFP has a positive impact on job satisfaction, its effect is residual compared to organisational support, which emerges as a key factor both directly and indirectly in improving employee well-being. Furthermore, significant differences are observed in the impact of these variables according to gender and family responsibilities, suggesting the need for personalised approaches in policy implementation. The results of this study are highly relevant for organisations and leaders in the tourism industry, as they provide empirical evidence on the importance of promoting job satisfaction through a culture of organisational support and the design of accessible, inclusive, and adaptive policies that consider the well-being and diverse needs of workers.

Acknowledgements

This publication has been made possible thanks to funds received from the Plan Propio - UCA 2022-2023, from the Universidad de Cadiz, and the INDESS Research Institute of the Universidad de Cadiz.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Acosta-González, H. N., & Marcenaro-Gutiérrez, O. D. (2021). The relationship between subjective well-being and self-reported health: Evidence from Ecuador. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 16(5), 1961–1981. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-020-09852-z

- Adams, A., & Golsch, K. (2021). Gender-specific patterns and determinants of spillover between work and family: The role of partner support in dual-earner couples. Journal of Family Research, 33(1), 72–98. https://doi.org/10.20377/jfr-373

- Anand, A., & Vohra, V. (2021). Alleviating employee work-family conflict: Role of organizations. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 28(2), 313–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-06-2019-1792

- Anderson, S. E., Coffey, B. S., & Byerly, R. T. (2002). Formal organizational initiatives and informal workplace practices: Links to work–family conflict and job-related outcomes. Journal of Management, 28(6), 787–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(02)00190-3

- Appelbaum, N. P., Lee, N., Amendola, M., Dodson, K., & Kaplan, B. (2019). Surgical resident burnout and job satisfaction: The role of workplace climate and perceived support. Journal of Surgical Research, 234, 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2018.08.035

- Arefin, M. S., Alam, M. S., Islam, N., & Molasy, M. (2020). Organizational politics and work-family conflict: The hospitality industry in Bangladesh. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 9(3), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-07-2019-0135

- Arslaner, E., & Boylu, Y. (2017). Perceived organizational support, work-family / family-work conflict and presenteeism in hotel industry. Tourism Review, 72(2), 171–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-09-2016-0031

- Baker, M. A., & Kim, K. (2020). Dealing with customer incivility: The effects of managerial support on employee psychological well-being and quality-of-life. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87(March), 102503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102503

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

- Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands-resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

- Bednarska, M. (2015). Moderators of job characteristics – Job satisfaction relationship in the tourism industry. Ekonomiczne Problemy Turystyki, 31(876), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.18276/ept.2015.3.31-01

- Bettac, E. L., & Probst, T. M. (2023). National work-family policies: Multilevel effects on employee reactions to work/family conflict. Work, 74(3), 919. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-205010

- Biedma-Ferrer, J. M., & Medina-Garrido, J. A. (2014). Impact of family-friendly HRM policies in organizational performance. Intangible Capital, 10(3), 448–466. https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.506

- Boeckmann, I., Misra, J., & Budig, M. J. (2015). Cultural and institutional factors shaping mothers’ employment and working hours in postindustrial countries. Social Forces, 93(4), 1301–1333. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou119

- Bourdeau, S., Ollier-Malaterre, A., & Houlfort, N. (2018). Not all work-life policies are created equal: Career consequences of using enabling versus enclosing work-life policies. Academy of Management Review, 44(1), 172–193. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0429

- Brunner, B., Igic, I., Keller, A. C., & Wieser, S. (2019). Who gains the most from improving working conditions? Health-related absenteeism and presenteeism due to stress at work. The European Journal of Health Economics, 20(8), 1165–1180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-019-01084-9

- Burke, R. (2010). Do managerial men benefit from organizational values supporting work-personal life balance? Women in Management Review, 25(2), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420010319606

- Caesens, G., Gillet, N., Morin, A. J. S., Houle, S. A., & Stinglhamber, F. (2020). A person-centred perspective on social support in the workplace. Applied Psychology, 69(3), 686–714. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12196

- Caplan, R. D., Cobb, S., French, J. R. P. J., Van Harrison, R., & Pinneau, S. R. J. (1975). Job demands and worker health: main effects and occupational differences (Institute for Social Research (ed.)). U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, Center for Disease Control, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health : for sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off. http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/007117197.

- Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., & Williams, L. J. (2000). Construction and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(2), 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1999.1713

- Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Sage Publications.

- Chin, W. W. (1998). Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Quarterly, 22(1), VII–XVI.

- Chin, W. W. (2003). A permutation procedure for multi-group comparison of PLS models. In M. Vilares, M. Tenenhaus, P. Coelho, V. Esposito Vinzi, & A. Morineau (Eds.), PLS and related methods: Proceedings of the international symposium PLS’03 (Vol. 3, pp. 33–43). Decisia.

- Clark, M. A., Rudolph, C. W., Zhdanova, L., Michel, J. S., & Baltes, B. B. (2017). Organizational support factors and work–family outcomes: Exploring gender differences. Journal of Family Issues, 38(11), 1520–1545. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15585809

- Claudia, M. (2018). The influence of perceived organizational support, job satisfaction and organizational commitment toward organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Indonesian Economy and Business, 33(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.22146/jieb.17761

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the social sciences. Erlbaum.

- Costantini, A., Dickert, S., Sartori, R., & Ceschi, A. (2021). Return to work after maternity leave: The role of support policies on work attitudes of women in management positions. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 36(1), 108–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-06-2019-0085

- Crucke, S., Kluijtmans, T., Meyfroodt, K., & Desmidt, S. (2022). How does organizational sustainability foster public service motivation and job satisfaction? The mediating role of organizational support and societal impact potential. Public Management Review, 24(8), 1155–1181. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1893801

- Dalgaard, V. L., Gayed, A., Hansen, A. K. L., Grytnes, R., Nielsen, K., Kirkegaard, T., Uldall, L., Ingerslev, K., Skakon, J., & Jacobsen, C. B. (2023). A study protocol outlining the development and evaluation of a training program for frontline managers on leading well-being and the psychosocial work environment in Danish hospital settings – A cluster randomized waitlist controlled trial. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15728-2

- Debnath, T. (2023). Work-from-home provides benefits to family and workplace that impact on job satisfaction: An evidence from Bangladesh. American Journal of Interdisciplinary Research and Innovation, 1(3), 69–75. https://doi.org/10.54536/ajiri.v1i3.1118

- DePasquale, N., Polenick, C. A., Davis, K. D., Moen, P., Hammer, L. B., & Almeida, D. M. (2017). The psychosocial implications of managing work and family caregiving roles: Gender differences among information technology professionals. Journal of Family Issues, 38(11), 1495–1519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15584680

- Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2015/39.2.02

- El Achkar, S. (2023). Cómo los datos pueden impulsar el trabajo digno en el sector turístico. In ILOSTAT Blog. International Labour Office. https://ilostat.ilo.org/es/blog/how-data-can-bolster-decent-work-in-the-tourism-sector/.

- European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. (2016). Psychosocial risks and stress at work. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. https://osha.europa.eu/en/themes/psychosocial-risks-and-stress.

- Faddila, S. P., & Senen, S. H. (2023). Employee relationships in the tourism industry: A systematic literature review (SLR) and bibliometric. West Science Interdisciplinary Studies, 1(12), 1445–1454. https://doi.org/10.58812/wsis.v1i12.465

- Families and Work Institute. (2012a). Benchmarking report on workplace effectiveness and flexibility – executive summary.

- Families and Work Institute. (2012b). Workplace effectiveness and flexibility benchmarking report.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Ganji, S. F. G., Johnson, L. W., Sorkhan, V. B., & Banejad, B. (2021). The effect of employee empowerment, organizational support, and ethical climate on turnover intention: The mediating role of job satisfaction. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 14(2), 311–329. https://doi.org/10.22059/IJMS.2020.302333.674066

- García-Cabrera, A. M., Lucia-Casademunt, A. M., Cuéllar-Molina, D., & Padilla-Angulo, L. (2018). Negative work-family/family-work spillover and well-being across Europe in the hospitality industry: The role of perceived supervisor support. Tourism Management Perspectives, 26(January), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2018.01.006

- Gip, H., Guchait, P., Paşamehmetoğlu, A., & Khoa, D. T. (2023). How organizational dehumanization impacts hospitality employees service recovery performance and sabotage behaviors: The role of psychological well-being and tenure. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(1), 64–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2022-0155

- Gordon, S., Tang, C. H., Day, J. (Hugo), & Adler, H. (2019). Supervisor support and turnover in hotels: Does subjective well-being mediate the relationship? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(1), 496–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2016-0565

- Grzywacz, J. G., & Marks, N. F. (2000). Reconceptualizing the work-family interface: An ecological perspective on the correlates of positive and negative spillover between work and family. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.111

- Hair Jr, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-10-2013-0128

- Hayat, A., & Afshari, L. (2022). CSR and employee well-being in hospitality industry: A mediation model of job satisfaction and affective commitment. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 51, 387–396. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.04.008

- Henseler, J. (2017). Bridging design and behavioral research with variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of Advertising, 46(1), 178–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2017.1281780

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Testing measurement invariance of composites using partial least squares. International Marketing Review, 33(3), 405–431. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-09-2014-0304

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

- ILO. (2017). ILO guidelines on decent work and socially responsible tourism. International Labour Office. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_dialogue/—sector/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_546337.pdf.

- Iqbal, M., Ahmad, S., Ullah, M., Siddiq, A., Ali, A., & Ali, N. (2022). Moderating effect of work-family conflict on the relationship of perceived organizational support and job satisfaction : A study of government commerce colleges of Kp, Pakistan. Journal of Positive School Psychology, 6(7), 2282–2291.

- Isfianadewi, D., & Noordyani, A. (2020). Implementation of coping strategy in work- family conflict on job stress and job satisfaction: Social support as moderation variable. Review of Integrative Business and Economics Research, 9(2), 223–239. https://search.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/implementation-coping-strategy-work-family/docview/2367741979/se-2?accountid=136549.

- Jamal, M. T., Alalyani, W. R., Thoudam, P., Anwar, I., & Bino, E. (2021). Telecommuting during COVID 19: A moderated-mediation approach linking job resources to job satisfaction. Sustainability, 13(20), 11449–11417. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011449

- Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2003). The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56(2), 303–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00152.x

- Kalliath, P., Kalliath, T., & Chan, C. (2017). Work–family conflict, family satisfaction and employee well-being: A comparative study of Australian and Indian social workers. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(3), 366–381. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12143

- Kashyap, E., & Kaur, S. (2021). Importance of work life balance : A review. Ilkogretim Online - Elementary Education Online, 20(5), 5068–5072. https://doi.org/10.17051/ilkonline.2021.05.567

- Kim, M. (Sunny), Ma, E., & Wang, L. (2023). Work-family supportive benefits, programs, and policies and employee well-being: Implications for the hospitality industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2022.103356

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of E-Collaboration, 11, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Kosec, Z., Sekulic, S., Wilson-Gahan, S., Rostohar, K., Tusak, M., & Bon, M. (2022). Correlation between employee performance, well-being, job satisfaction, and life satisfaction in sedentary jobs in Slovenian enterprises. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610427

- Kossek, E. E., Colquitt, J. a., & Noe, R. a. (2001). Caregiving decisions, well-being, and performance: The effects of place and provider as a function of dependent type and work-family climates. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069335

- Kurtessis, J. N., Eisenberger, R., Ford, M. T., Buffardi, L. C., Stewart, K. A., & Adis, C. S. (2017). Perceived organizational support: A meta-analytic evaluation of organizational support theory. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1854–1884. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315575554

- Lee, Y., & Kramer, A. (2022). Understanding the (lack of) utilization of work-family practices: A multilevel perspective. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 29(4), 899–918. https://doi.org/10.1108/CCSM-05-2021-0081

- Leger, K. A., Lee, S., Chandler, K. D., & Almeida, D. M. (2022). Effects of a workplace intervention on daily stressor reactivity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 27(1), 152–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000297

- Levey, N. (2023). Wellness in the hospitality industry - Guests vs. employees. Journal of Global Hospitality and Tourism, 2(1), 7–9. https://doi.org/10.5038/2771-5957.2.1.1017

- Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 1297–1343). Rand McNally.

- Lyonette, C., & Baldauf, B. (2019). Family friendly working policies and practices: Motivations, influences and impacts for employers. October, 1–76.

- Martins, D., & Silva, S. (2023). Paradoxes in tourism and hospitality sectors: From work-life balance to work-life conflict in shift work. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies, 340(June), 483–496. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-9960-4_42

- Mascarenhas, C., Galvão, A. R., & Marques, C. S. (2022). How perceived organizational support, identification with organization and work engagement influence job satisfaction: A gender-based perspective. Administrative Sciences, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci12020066

- Maszura, L., & Novliadi, F. (2020). The influence of perceived organizational support on work-life balance. International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies, 22(1), 182–188.

- McKee-Ryan, F. M., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53

- Medina-Garrido, J. A., Biedma-Ferrer, J. M., & Bogren, M. (2023). Organizational support for work-family life balance as an antecedent to the well-being of tourism employees in Spain. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 57(September), 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2023.08.018

- Medina-Garrido, J. A., Biedma-Ferrer, J. M., & Ramos-Rodríguez, A. R. (2017). Relationship between work-family balance, employee well-being and job performance. Academia Revista Latinoamericana de Administración, 30(1), 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARLA-08-2015-0202

- Medina-Garrido, J. A., Biedma-Ferrer, J. M., & Ramos-Rodríguez, A. R. (2021). Moderating effects of gender and family responsibilities on the relations between work–family policies and job performance. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(5), 1006–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2018.1505762

- Medina-Garrido, J. A., Biedma-Ferrer, J. M., & Rodríguez-Cornejo, M. V. (2021). I quit! Effects of work-family policies on the turnover intention. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041893

- Medina-Garrido, J. A., Biedma-Ferrer, J. M., & Sánchez-Ortiz, J. (2020). I can’t go to work tomorrow! Work-family policies, well-being and absenteeism. Sustainability, 12(14), 5519. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145519

- Memili, E., Patel, P. C., Holt, D. T., & Gabrielle Swab, R. (2023). Family-friendly work practices in family firms: A study investigating job satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 164(May), 114023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114023

- Mihalache, M., & Mihalache, O. R. (2022). How workplace support for the COVID-19 pandemic and personality traits affect changes in employees’ affective commitment to the organization and job-related well-being. Human Resource Management, 61(3), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.22082

- Montañés-Del-Río, MÁ, & Medina-Garrido, J. A. (2020). Determinants of the propensity for innovation among entrepreneurs in the tourism industry. Sustainability, 12(12), 5003. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12125003

- Nahar, M., Arshad, M., & Ab Malik, Z. (2015). Quality of human capital and labor productivity: A case of Malaysia. International Journal of Economics, Management and Accounting, 23(1), 37–55.

- Ng, J. S., & Chin, K. Y. (2021). Potential mechanisms linking psychological stress to bone health. International Journal of Medical Sciences, 18(3), 604–614. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.50680

- Nordenmark, M. (2021). How family policy context shapes mental wellbeing of mothers and fathers. Social Indicators Research, 158(1), 45–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02701-y

- Nordenmark, M., & Alm, N. (2020). Societies work / family conflict of more importance than psychosocial working conditions and family conditions for mental wellbeing. Societies, 10(67), 1–15.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). The assessment of reliability. Psychometric Theory, 3, 248–292.

- Park, J. Y., Hight, S. K., Bufquin, D., de Souza Meira, J. V., & Back, R. M. (2021). An examination of restaurant employees’ work-life outlook: The influence of support systems during COVID-19. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102992

- Park, C. L., Kubzansky, L. D., Chafouleas, S. M., Davidson, R. J., Keltner, D., Parsafar, P., Conwell, Y., Martin, M. Y., Hanmer, J., & Wang, K. H. (2022). Emotional well-being: What it is and why it matters. Affective Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-022-00163-0

- Poggesi, S., Mari, M., & De Vita, L. (2019). Women entrepreneurs and work-family conflict: An analysis of the antecedents. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(2), 431–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0484-1

- Quezada, N. M. (2022). An exploration of the relationship between social-emotional well-being and health behaviors of urban youth. State University of New York.

- Reimann, M., Schulz, F., Marx, C. K., & Lükemann, L. (2022). The family side of work-family conflict: A literature review of antecedents and consequences. Journal of Family Research, 34(4), 1010–1032. https://doi.org/10.20377/jfr-859

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH. http://www.smartpls.com.

- Roemer, A., & Harris, C. (2018). Perceived organisational support and well-being: The role of psychological capital as a mediator. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 44, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v44i0.1539

- Schulz, F., & Reimann, M. (2022). Parents’ experiences of work-family conflict: Does it matter if coworkers have children? Journal of Family Research, 34(4), 1056–1071. https://doi.org/10.20377/jfr-780

- Semlali, S., & Hassi, A. (2016). Work–life balance: How can we help women IT professionals in Morocco? Journal of Global Responsibility, 7(2), 210–225. https://doi.org/10.1108/JGR-07-2016-0017

- Stewart, L. M., Sellmaier, C., Brannan, A. M., & Brennan, E. M. (2022). Employed parents of children with typical and exceptional care responsibilities: Family demands and workplace supports. Journal of Child and Family Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02363-5

- Tepavčević, J., Blešić, I., Petrović, M. D., Vukosav, S., Bradić, M., Garača, V., Gajić, T., & Lukić, D. (2021). Personality traits that affect travel intentions during pandemic COVID-19: The case study of Serbia. Sustainability, 13(22). https://doi.org/10.3390/su132212845

- Tepavčević, J., Vukosav, S., & Bradić, M. (2021). The impact of demographic factors on work-family conflict and turnover intentions in the hotel industry. Menadzment u hotelijerstvu i turizmu, 9(2), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.5937/menhottur2102025T

- Vadvilavičius, T., & Stelmokienė, A. (2020). Evidence-based practices that deal with work-family conflict and enrichment: Systematic literature review. Business: Theory and Practice, 21(2), 820–826. https://doi.org/10.3846/btp.2020.12252

- Warr, P. (1990). The measurement of well-being and other aspects of mental health. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(3), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00521.x

- Wattles, M. G., & Harris, C. (2003). The relationship between fitness levels and employee’s perceived productivity, job satisfaction, and absenteeism. Journal of Exercise Physiology Online, 6(1), 24–32.

- Werts, C. E., Linn, R. L., & Jöreskog, K. G. (1974). Intraclass reliability estimates: Testing structural assumptions. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 34(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447403400104

- Xiong, W., Huang, M., Okumus, B., Leung, X. Y., Cai, X., & Fan, F. (2023). How emotional labor affect hotel employees’ mental health: A longitudinal study. Tourism Management, 94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104631

- Yadav, V., & Sharma, H. (2023). Family-friendly policies, supervisor support and job satisfaction: Mediating effect of work-family conflict. Vilakshan - XIMB Journal of Management, 20(1), 98–113. https://doi.org/10.1108/XJM-02-2021-0050

- Yang, X., & Jo, W. M. (2022). Roles of work-life balance and trait mindfulness between recovery experiences and employee subjective well-being: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 52, 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.08.005

- Zeng, X., Zhang, X., Chen, M., Liu, J., & Wu, C. (2020). The influence of perceived organizational support on police job burnout: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00948

- Zhang, T. (2018). Employee wellness innovations in hospitality workplaces: Learning from high-tech corporations. Journal of Global Business Insights, 3(2), 52–66. https://doi.org/10.5038/2640-6489.3.2.1003

- Zhao, X. R., Ghiselli, R., Wang, J., Law, R., Okumus, F., & Ma, J. (2020). A mixed-method review of work-family research in hospitality contexts. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.08.006

- Zhao, X. R., Wang, J., Law, R., & Fan, X. (2020). A meta-analytic model on the role of organizational support in work-family conflict and employee satisfaction. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(12), 3767–3786. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2020-0371