ABSTRACT

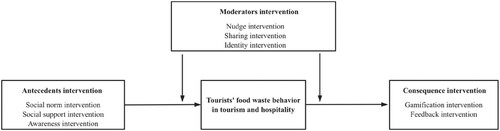

Despite the fact that food waste in tourism is significant, research into the development of effective social media interventions to address this issue, is lacking. This study provides a comprehensive narrative review of the social media interventions that have been used to reduce food waste. Three intervention types were identified: (1) antecedent (social norm, social support, and awareness), (2) moderator (platform nudge, sharing, and identity), and (3) consequence (gamification and feedback). By establishing a novel social media intervention framework, this study advances tourism and hospitality knowledge relating to the causes and impacts of social media interventions on reducing food waste. It provides important insights on ways that social media interventions can be used to leverage environmental sustainability in tourism. This study calls for future research that can more effectively and accurately measure the impact of social media interventions.

1. Introduction

In tourism and hospitality, the consumption of food has expanded from a basic need, to an experience and attraction (Henderson, Citation2009), becoming a significant driver for tourists (Kim & Eves, Citation2012). However, the food waste generated in the tourism and hospitality industry is substantial, contributing significantly to both economic losses and environmental challenges (Dhir et al., Citation2020). As a major contributor, the hospitality industry ranks among the top three waste generators, accounting for approximately 12% of total waste (Filimonau & Delysia, Citation2019), particularly in hotel buffets where there is an unlimited supply of food (Juvan et al., Citation2018). Plate waste alone, comprises more than half of the industry’s total food waste (Sundt, Citation2012).

Given the significant impact of food waste, studies have explored various interventions aimed at changing tourist behaviour, in order to reduce the quantity. In the context of tourism, however, a hedonic environment that is characterised by leisure and enjoyment, the task of changing peoples’ behaviour is particularly challenging (Dolnicar & Grün, Citation2009). Research suggests that traditional pro-environmental appeals do not significantly improve the corresponding behaviour in hotels (Dolnicar et al., Citation2017), and it has been observed that the interventions found to be effective in a person’s home context, cannot be generalised to the wider tourism context (Dolnicar & Grün, Citation2009). A possible explanation for this finding is that tourists typically do not benefit directly from any monetary savings related to displaying the desirable behaviour (Dolnicar et al., Citation2019). On the contrary, to elicit this behaviour, a tourist could actually be required to sacrifice a degree of satisfaction and experience. Considering these challenges, social media intervention has emerged as a particularly promising approach to addressing food waste in tourism and hospitality. First, social media is already integrated into people’s daily routines, and therefore, interventions based on social media is unlikely to impose additional experiential burdens on a person (Laranjo, Citation2016). Second, many social media intervention strategies enable participants to gain positive social recognition and enhance their self-image on social media platforms (Back et al., Citation2010; Choi & Seo, Citation2017). These self-interested motivations can drive individual actions.

Social media intervention, as a novel intervention method, has increasingly garnered attention from scholars, and its potential to replicate face-to-face interventions has been highlighted. Scholarly inquiries into social media intervention have investigated a diverse range of intervention mechanisms that impact behavioural outcomes. For example, Guenther et al. (Citation2021) have proven the effectiveness of social media interventions for the promotion of physical activity, and some scholars have also employed social media intervention to reduce food waste (Comber & Thieme, Citation2013). However, there is yet to be a systematic assessment of this rapidly growing research area, or any advice on how marketers may be able to capitalise on this new tool. Initial observations reveal a set of inconsistent findings on the effectiveness of social media intervention in this area. Young et al. (Citation2017a), for example, implemented three interventions, and found that social media interventions were an efficient tool for reducing consumers’ food waste. Grainger and Stewart (Citation2017), however, argued that social media could not be used as an effective behaviour-changing agent in the realm of food waste. This highlights both the diversity and the fragmented nature of the literature relating to the use of social media intervention to reduce food waste. Given the current ‘transitional’ nature of the literature, there is a need to create an overarching understanding of the role social media can play; this will assist in the setting of future research agenda and will provide practitioners with more accurate information from which to make informed decisions. As stated by Murphy et al. (Citation2018), future social media intervention research in tourism should be encouraged to widen the research horizon beyond conventional practices. To this end, this study conducted a narrative review of social media intervention to reduce food waste in tourism and hospitality to achieve the following research objectives: (1) Assess the performance, productivity, and impact of relevant authors and journals in using social media intervention to reduce food waste; (2) Analyse the intellectual interactions and structural connections among authors and thematic areas; (3) Identify and evaluate the research that underpins social media interventions designed to reduce food waste in tourism and hospitality.

This study makes important contributions to extant tourism and hospitality literature. It offers a comprehensive review of the empirical research progress relating to social media intervention in tourism, and in doing so, has developed a fundamental knowledge of social media interventions in reducing food waste. It also directly addresses the call of Dolnicar (Citation2020) to develop more innovative approaches in tackling the environmental sustainably issues in tourism. Most importantly, the study presents an integrative framework that will serve as a guide for future research on social media interventions in tourism. This framework synthesises evidence from existing research across various disciplines, and examines the impact of different types of social media interventions on behaviours around food waste. It offers the tourism and hospitality sectors a valuable tool by incorporating essential antecedent and consequence interventions, thereby enhancing current understanding of the underlying mechanisms. This review also provides significant implications that will guide the tourism industry in systematically developing effective social media intervention designs to reduce food waste. It details the principal methodological approaches and the steps that practitioners can utilise to design and experimentally test interventions aimed at reducing food waste by tourists at destinations. This paves the way for further research endeavours using social media interventions to reduce food waste.

2. Literature review

2.1. Social media intervention

Social media, with its potential to reach a large audience, creates unprecedented opportunities to trigger behavioural changes (Young et al., Citation2017a). Previous literature has examined social media intervention in the contexts of alcohol consumption (Moreno & Whitehill, Citation2014), diet and nutrition (Hsu et al., Citation2018), physical activity (Guenther et al., Citation2021), smoking cessation (Naslund et al., Citation2017) and weight loss (Hales et al., Citation2014). However, a review of existing literature reveals that there is no agreed framework for effectively measuring the effectiveness of social media intervention. This is due to the fact that social media presents significant differences from other traditional types of intervention.First, instead of requiring participants to establish new connections, social media intervention can take direct advantage of a participant’s existing social networks, thereby avoiding the ‘stranger phenomenon’ (Hunter et al., Citation2019). This advantage can hardly be found in other types of intervention. Second, social networks created in social media can be as authentic as real-life social structures, and these social networks can vary between loose and tight structures (Laranjo et al., Citation2015). Some scholars consider that these physical social networks possess the potential to simulate face-to-face interactions, which are a key element of effective behavioural interventions (Young et al., Citation2017a). Thus, social media interventions have genuine characteristics. Moreover, as social media has gradually become part of people’s daily lives, social media intervention has great potential to increase engagement, as it can easily integrate into a person’s daily routines and habits without extra experimental burden (Laranjo, Citation2016). Finally, there are no comparable platforms with as great an influence as social media. Social media has billions of regular users worldwide, which minimises retention issues and lack of adherence to interventions (Duong, Citation2020).

Studies on social media interventions have primarily focused on two streams. The first stream has explored the effectiveness of social media intervention in triggering behavioural changes among the target group, focusing mainly on four key areas: (1) the consumption of addictive consumer products (e.g. tobacco, alcohol), (2) health-related lifestyle practices (e.g. physical activity, weight loss, weight maintenance, diet and nutrition), (3) disease-related prevention and rehabilitation (e.g. HIV infection prevention, suicide); and (4) publicity campaigns (e.g. seat belt use, road safety, vaccinations). These types of investigation aim to ascertain the efficacy of social media interventions in fostering positive changes in health-related behaviours among extensive population bases. The second stream has focused on identifying the behavioural change technique used in effective social media interventions. For example, Welch et al. (Citation2018) used behaviour change techniques to assess the effects of social media intervention on health-related behaviours, and identified that a series of interventions, such as goal setting, social support, and monitoring of behaviour, positively influenced physical and psychological health outcomes among adults. Similarly, Hsu et al. (Citation2018) determined the effectiveness of five eligible social media interventions (social support, goal setting, self-monitoring, feedback, and demonstration of behaviour) on enhancing nutritional intake behaviours in adolescents. These examples of social media interventions provide a rich source from which a possible common mechanism associated with the reduction of food waste in tourism and hospitality can be identified.

Additionally, a comprehensive review of the behavioural change theories utilised by social media interventions was undertaken (supplementary material). This review revealed that the prevalent behavioural change theories used in social media interventions are centred around ‘intentions’, ‘attitudes’, and ‘beliefs’. These theories offer valuable insights into the various aspects of human behaviour displayed on social media platforms.

2.2. Food waste behaviour in tourism and hospitality

Food waste is a multifaceted issue, occurring at various stages of the food lifecycle. This study focuses purely on tourists and hotel guests, and the reduction of eatable ‘plate waste’, which is food served, but not eaten. In tourism and hospitality, plate waste is substantial, constituting more than half of the total food waste within the sector (Sundt, Citation2012). Existing literature () has shown that plate waste is the most easily preventable form of food waste in hospitality (Beretta & Hellweg, Citation2019), with up to 92% of plate waste being avoidable (Papargyropoulou et al., Citation2016).

Table 1. Representative research on food waste behaviour in tourism and hospitality.

The reduction of food waste remains an underexplored area in tourism (Dolnicar et al., Citation2020; Filimonau & Delysia, Citation2019), and the research that has been undertaken has mainly focused on two distinct areas. The first has explored the main determinants of the issue (Filimonau & Delysia, Citation2019; Juvan et al., Citation2018), while the second has focused on identifying the fundamental approaches to reducing food waste (Filimonau & Delysia, Citation2019; Okumus et al., Citation2020). It is the first group, the one identifying the factors that influence food waste in tourism, that has produced the largest body of work. For example, Dolnicar and Juvan (Citation2019) devised a plate waste drivers model specifically for hospitality buffets. Within this model, they identified 12 influential factors, suggesting that each of which could be targeted for interventions to reduce place waste. These included situations where individuals’ appetites exceeded their actual consumption capacity, and reluctance to make multiple trips to the buffet due to laziness.

The second group has explored solutions to reduce tourists’ food waste. The most typical approach has been to develop and empirically test interventions aimed at reducing food waste among tourists (Dolnicar et al., Citation2020). For example, Kallbekken and Sælen (Citation2013) proved that reducing plate size by three centimetres could effectively reduce plate waste by 20%. In addition, Chang (Citation2022) employed a field intervention to examine the joint effects of serving styles and inducements on food waste. The results revealed that combining the serving style of buffet self-service, with persuasive moral inducements, generated minimal food waste. Other effective interventions have included penalties (Kuo & Shih, Citation2016), incentives (Dolnicar et al., Citation2020) and reduced food portions (Freedman & Brochado, Citation2010).

In fact, food waste behaviour presents its distinctiveness in tourism. First, the hedonic nature of tourism means that tourist behaviour is particularly hard to change (Dolnicar et al., Citation2019). Many interventions that have been proven to be effective for environmental behaviour change in non-tourism settings, fail to translate into tourism settings (Dolnicar & Grün, Citation2009). The challenge is that tourism’s inherent hedonistic nature, centred around enjoyment, is in stark contrast to the effort and sacrifices required to reduce food waste (Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014). This enjoyment-focused environment significantly lowers the inclination for tourists to engage in eco-friendly practices, even those who actively engage in anti-food waste practices at home (Macinnes et al., Citation2022). Second, people may produce more plate waste on vacation than they would in their home environments (Juvan et al., Citation2018). The role of food in tourism is complex, because of unfamiliar contexts, and its symbolic meaning in the travel setting. Tourists like to try many different foods, because people tend to focus primarily on enjoyment (Dolnicar et al., Citation2017). This change in focus alters a person’s behaviour, which typically becomes less environmentally friendly (Dolnicar & Grün, Citation2009). Finally, the inherent mobility of tourists presents a significant challenge to the task of altering tourist behaviour. Habit formation and modification require time, and the typically brief duration of a tourist’s stay at a destination, limits the opportunity to influence their behaviours and habits, making short-term changes difficult to achieve. Current interventions focusing on reducing food waste behaviour, such as modifying plate size and implementing temporary rewards and punishments, are immediate, rather than long-term assessments. In addition, food waste behaviour is likely to persist during subsequent meals or at the following destinations, where tourists may not receive instant intervention. As such, it is a challenge to alter behaviours in the long term through persistent interventions, and therefore, social media, with its extensive coverage and subtle influencing nature, presents enormous opportunities to provide food waste-related interventions.

2.3. Reviews of social media intervention in changing tourist food waste behaviour

To comprehensively explore the potential of social media interventions in reducing food waste, the scope of the review was not limited to tourism and hospitality but rather, the study encompassed all studies that used social media interventions to reduce food waste, examining the implications of the various social media interventions for tourism and hospitality. Despite the limited research on the efficacy of social media interventions in changing waste behaviour in tourism and hospitality, research has indicated that these types of interventions have considerable potential in shaping the food-related social norms and sustainable tourism behaviours of tourists (Chong et al., Citation2022; Simeone & Scarpato, Citation2020).

A review of existing food waste literature on the topic of social media intervention indicated that there is no consensus on which social media intervention mechanisms trigger behavioural changes in food waste. Based on the sharing attributes of social media, the first stream of studies regarded social media tools as a means by which consumers could abort the food-wasting process. Lazell (Citation2016) discussed the role that ‘sharing’ on social media sites had, on preventing food waste. The author also identified several barriers to using social media tools as behavioural change interventions. Similar results were observed by Lim et al. (Citation2017), who discovered that sharing social recipes based on those used by individuals or households was perceived to be just as effective in food waste reduction. The second stream of studies revealed that social media could reduce food waste by incorporating social norms, such as social support and competition, in addition to sharing. For instance, Comber et al. (Citation2013) incorporated elements of group identification and competition on Facebook to increase group engagement in food waste online activity, which successfully reduced the amount of waste people produced. The third stream of studies emphasised that social media was an effective information channel for spreading relevant information about reducing food waste. For example, Lodes (Citation2019) developed a reduced food waste campaign linked with Instagram and Facebook pages, to gauge the attitudes of food waste among followers, the result reported a slight decrease in reducing food waste category from baseline to the intervention period.

3. A framework of social media interventions aimed at reducing food waste

Behavioural change research often employs a twofold classification framework, categorised as ‘antecedent’ or ‘consequence’, to outline the variety of intervention types (Stöckli et al., Citation2018). Antecedent interventions (e.g. informational interventions and social norms), modify the context preceding the target behaviour, and are always placed on the input side, while consequence interventions (e.g. comparison and increased pleasure), alter behavioural outcomes and are always positioned at the output side. Building on the research of Stöckli et al. (Citation2018), a general twofold classification was adopted. This is a straightforward framework that can clearly present a broad spectrum of intervention types used for reducing food waste through behavioural changes.

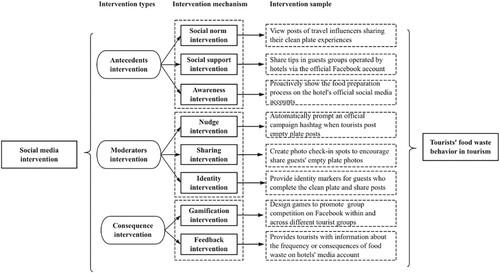

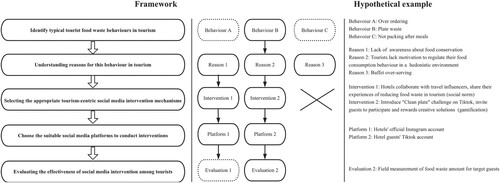

Based on the framework, the current study collected, grouped, and analysed evidence on reducing food-waste through social media intervention. provides an overview of three classifications that analysed social media intervention in reducing food waste. Within each intervention section, defined and relevant evidence is included; this serves as a basis for a framework of effective social media intervention in reducing food waste. This, in turn, also generates a research agenda to better understand how to effectively reduce food waste in tourism.

Figure 1. (A) Social media interventions for reducing food waste. (B). Representative examples of the application of social media interventions in reducing food waste in tourism.

4. Method

4.1. Data collection

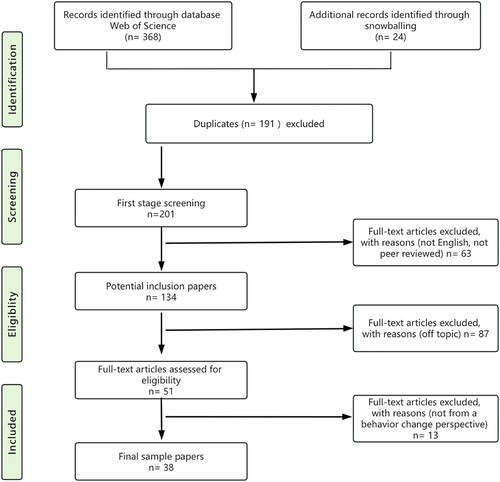

The study followed the systematic literature review process of Wohlin et al. (Citation2020), combining a database-oriented search strategy with a snowballing approach. Peer-reviewed articles written in English and published before June 2024 in Web of Science were searched for using search terms such as ‘food waste’ OR ‘food loss’ OR ‘food disposal’ OR ‘food conservation’ OR ‘food preservation’, and, ‘social media’ OR ‘social network’ OR ‘digital media’, and ‘behaviour change’, within the title, keyword, and abstract fields. The initial search resulted in 368 potentially relevant articles. The snowballing approach was then utilised, and this resulted in an additional 20 articles. After removing duplicates, a total of 197 articles were included in the initial database for further analysis. Book chapters, works-in-progress, and papers labelled as ‘short papers’, were excluded. As a result, 38 articles with a focus on social media intervention were reviewed. The detailed process is presented in .

4.2. Data analysis

Content analysis and a quantitative systematic review approach were used. Content analysis offered a text-based examination of articles for key themes and intervention mechanisms relating to the reduction of food waste, whereas the quantitative systematic literature review synthesised the diverse body of research by providing a set of numerical data to represent key aspects. This systematic approach was successful in providing an overview of social media interventions around the reduction of food waste.

The purpose of the content analysis was to discover key intervention types and to categorise these into a theoretical framework. In a quantitative systematic literature review, researchers individually analysed each article, extracting and categorising information under the categories below, which included:

the author and/or institution

basic information regarding the articles (e.g. journal/citation/year)

the nature of the research (e.g. empirical/conceptual)

the social media platforms studied

populations analysed using empirical studies

5. Result

5.1. Bibliometric analysis

5.1.1 The most productive authors and outlets in research area

Published numbers and citation bursts of articles reflect the evolution of research hotspots. William Young is the most productive author in this area. Young et al (Citation2017a) conducted a landmark study, which field-test the effect of social media intervention on food waste behaviour. Furthermore, Comber and Thieme (Citation2013) explored the role of social media intervention in recycling and reducing food waste, their finding revealed how social media intervention raises self-reflection and re-evaluation, further changing behaviour.

5.1.2 The keyword co-occurrence and co-author analysis

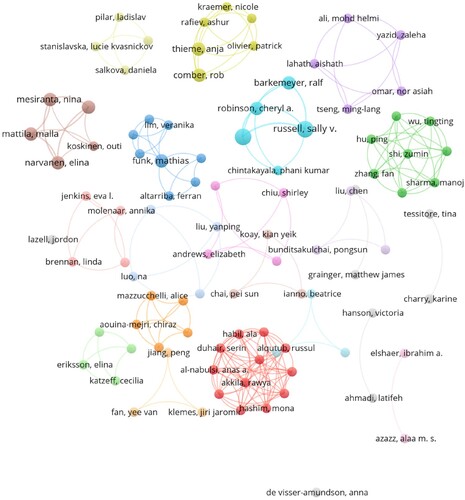

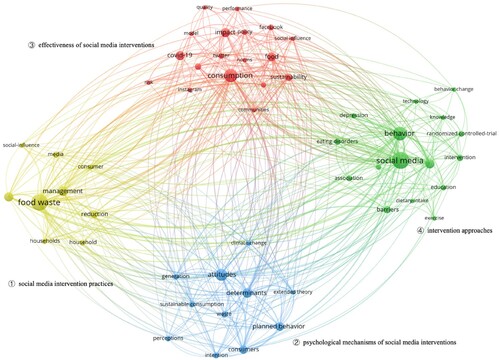

Keyword co-occurrence and co-author analysis were performed to explore intellectual interactions and structural connections of authors and themes. Keyword co-occurrence analysis identified four core thematic clusters (): (1) the practices of social media interventions, (2) the psychological mechanisms of social media interventions, (3) the effectiveness of social media interventions and (4) intervention approaches. Specifically, Cluster 1 focuses on the practical applications of social media interventions. This cluster targets specific points within the food behaviour chain, such as purchasing, storing, cooking, and disposal, and develops intervention strategies tailored to these points. Cluster 2 explores the psychological mechanisms of social media interventions. This cluster contains topics centred on exploring how individual attitudes, group identity, and social norms influence their food waste behaviours. Cluster 3 evaluates the effectiveness of social media interventions. This cluster compares the effectiveness of social media interventions with other intervention approaches in reducing food waste. Cluster 4 focuses on intervention approaches. This cluster mainly examines different measurement methods, media platforms, and theoretical models of social media interventions.

Figure 3. Intellectual interactions and structural connections of themes in social media intervention to reduce food waste.

The author collaboration network reveals a dispersed and scattered interconnectedness within this topic (). The network illustrates numerous small, interconnected author groups. Among these groups, Akkila Rawya emerged as the most influential author within this network, closely followed by Young William and Sally Russell. Notably, Young William and Sally Russell stand out as notable influencers, with their collaborative efforts shaping the discourse within the field. Comber Rob and Thieme Anja also contribute significantly to collaborative endeavours within the academic community. Overall, the realm of social media intervention in reducing food waste exhibits dynamic co-authorship patterns with significant collaborative efforts among authors.

5.2. Antecedents

5.2.1 Social norms

Using social norm intervention in social media has emerged as a promising intervention to change behaviour. Nisa et al. (Citation2017) describe social norms as, ‘shared rules about how to behave as a member of society, providing guidance of what is considered the “right” behaviour from an ethical standpoint' (p. 356). Many social media food-related posts incorporate certain social contexts, such as dining with friends, or eating at a restaurant, and Qutteina et al. (Citation2019) suggest that within these contexts, the posts may also convey food-related social norms. Furthermore, social media platforms such as Facebook enable users to share images, likes, and comments, and to engage in various interactions that also communicate social norms relating to food. Consequently, social media provides a novel way for conveying and promoting the social norms associated with food behaviours. For instance, social media platforms frequently employ images to suggest how users can make environmentally friendly food choices, and gauge approval for such behaviour through the number of ‘likes’ on posts. As such, social media can be harnessed to leverage social norms in efforts to reduce food waste. Notably, some studies have demonstrated that utilising the priming effects of social norms can effectively encourage users to share posts about healthy food, and to consume more low-energy-dense food (Coary & Poor, Citation2016). While there is substantial evidence supporting the influencing effects of social norms on guiding behaviour towards pro-environmental choices (Farrow et al., Citation2017), no research has experimentally manipulated social norms on social media to specifically target food waste behaviour.

5.2.2 Social support

Social support refers to ‘actions such as expressing suggestions, exchanging emotional concerns, and disseminating information that generates in people the feeling of being loved, supported, respected, appreciated, and part of a group’ (Mazzucchelli et al., Citation2021, p. 50). Social support not only reflects other users’ concerns and feelings about a specific item, it also conveys recommendations aimed at aiding others in resolving their issues. Social support intervention on social media, which allows for two-way communication among peers or the public, presents an immense opportunity to facilitate behavioural changes in food waste. An example of social support intervention is the application, ‘Active Team’, developed for Facebook by Maher et al. (Citation2015), which tested whether social media support could enhance daily walking steps. Participants were allocated into teams consisting of three to eight existing Facebook friends. The application encouraged friendly competition among team members and fostered peer encouragement and support.

Another distinctive attribute of social media is the occurrence of decision-making within a virtual social setting (Gimpel et al., Citation2021). Through social relationships and interactions, social media can provide social support with significant social value (Wang et al., Citation2019), such as satisfying the psychological needs of individuals, enhancing their well-being, and fostering connections that encourage mutual support among peers (Laurenceau et al., Citation1998). The anticipation of a sequence of support from social media platforms, creates a special meaning and feeling that can positively influence food waste, such as establishing a social media group on the platform and encouraging members to share their experiences and success stories in food waste reduction. Social media platforms can also be utilised to gather data and feedback, which can be used to track changes in members’ food-related behaviours.

5.2.3 Awareness

Leveraging awareness interventions is viewed as the most popular option for triggering behavioural change. This is where strategies are implemented to raise people’s awareness of problems and change their behaviour, by informing them of the consequences of desired and undesired behaviour. Social media offers the capability to target specific audiences at a lower cost in comparison with traditional advertising methods (Shawky et al., Citation2019). In fact, social media platforms have been found to be an effective intervention environment to change individual awareness of food waste. When using an intervention to reduce food waste in tourism, the typical behavioural sequence can be delineated into several key actions, such as selecting restaurants, ordering food, dining, and packaging leftovers. Each of these actions can be intervened through social media to increase people’s awareness re the reduction of food waste. For instance, social media campaigns can mobilise tourists to take discreet actions, such as ordering based on the number of people from the beginning, and not over–ordering.

5.3. Moderator

5.3.1 Social media platform nudges

Nudging, is a ‘behavioural economics approach relying on choice architecture and positive reinforcement, which can change behaviours regardless of conscious or unconscious drivers’ (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2009). As a simple intervention type, nudging changes a person’s choice framework and gently guides them towards a predetermined direction, without impinging on their freedom of choice. Research has demonstrated that nudges can reduce food waste, (e.g. a ‘reminder’ nudge for food waste behaviour) (Bernstad, Citation2014), reduce plate size, and provide social cues (Kallbekken & Sælen, Citation2013). More recently, it has been reported that social media nudges, such as visual prompts or simple reminders on social media platforms, have been likely to have driven and changed tourists’ food waste behaviour. For example, Charry and Tessitore (Citation2021) showed that a social media account with many followers can promote healthy food consumption, and that a large number of followers does act as an effective social push. Similarly, Kay et al. (Citation2023) found that social media nudge priming is likely to nudge healthy food consumption. Specifically, they proposed that discreetly featuring healthy beverages in the backdrop of Instagram images could be an effective way to encourage people to adopt healthier drink choices.

5.3.2 Sharing

The emergence of digital technologies has given rise to innovative business models in the food industry, particularly in the form of food-sharing online platforms; their emergence promotes food-related sharing and optimises the use of existing resources (Martin, Citation2016). Pinterest, for example, with 465 million active monthly users, describes itself as, ‘a virtual discovery engine for finding ideas like recipes, home and style inspiration, and more’. One notable aspect of Pinterest is its recipe curation, which has established itself as one of the platform’s most sought-after content categories. Users can leverage the platform to invite others to share posts, or communicate messages, thereby disseminating food-related information to reduce food waste. A study by Guidry et al. (Citation2023) found that Pinterest users frequently engage with the platform for food and recipe-related purposes, with 54.7% sharing recipes at least once a week. Consequently, sharing food or food-related information on such platforms is increasingly seen as a promising solution to combat food waste. Another study by Lazell (Citation2016) adopted a sharing-based interventional approach, allowing university participants to share photos of their food on social media platforms. While the results did not reveal a significant effect, the study still underscored the potential of food sharing on social media as a means of preventing food waste.

5.3.3 Identity

Identity refers to information about an individual and their activities. Identity in social media is often personalised by participants through user profiles. Some social media platforms (e.g. Twitter and Instagram) offer specific tools, such as hashtags (content marked with a # sign) that enable users to identify with particular groups and foster a sense of belonging. Numerous studies on social media have highlighted the role of online social identification (Mikal et al., Citation2016). Notably, younger generations of online users tend to identify strongly with online groups, even surpassing their tendencies to identify with traditional offline peer groups (Lehdonvirta & Räsänen, Citation2011). Identity on social media has also proven effective in influencing food-related behaviour. As an example, vegans, considered a minority group, utilise social media to strengthen their ‘identity bubble’ (Kaakinen et al., Citation2020). They aim to foster a sense of belonging and community within their group while also advocating for their dietary practices against conventional norms (Costa et al., Citation2019; Davis & Papies, Citation2022).

Similarly, consumers employ their identity to showcase their food preferences and attitudes. The attitudes exhibited within an online food group by its members have the potential to impact users’ dietary motivations (Blundell & Forwood, Citation2021). This influence could prompt certain users to consider altering their eating habits, such as shifting from meat to more sustainable alternatives (Pop et al., Citation2020). Thus, strategically leveraging identity shows promise for reducing food waste among tourists. Researchers could design a discussion on a social media platform such as Facebook, where users (tourists) could edit their own digital identities and also view those of others. Tourists who reduce food waste could obtain a Facebook Badge and incorporate it into their profiles. This badge would enable them to display prominent intervention messages and inspire other users to reduce food waste.

5.4 . Consequence

5.4.1 Gamification

Gamification is defined as ‘the use of game design elements in a non-gaming context to motivate user activity’ (Cugelman, Citation2013). Incorporating gamification apps into social media-based interventions can increase interventional effectiveness. The primary reason is that gamification effectively engages individuals through entertaining activities, encompassing games, challenges, or even the virtual community. Comber and Thieme (Citation2013) have adopted an ‘intelligent bin’ that automatically catches food waste to collect and measure household food waste. This intelligent trash device installs a system consisting of trash and a custom BinLeague gamification component on Facebook. This gaming approach has effectively captivated not only a range of individuals, but entire households, encouraging competition aimed at reducing food waste. Despite these positive outcomes in triggering people’s behavioural attitudes towards food waste, there is currently limited use of social media gamification interventions to reduce food waste.

5.4.2 Feedback

Feedback involves providing a person with information concerning the outcomes of engaging in a specific behaviour. This makes the results of the desired behaviour more noticeable, thereby increasing the likelihood of behavioural change. In the case of social media intervention, feedback refers to the intervention manner in which this data or information is returned to the user, such as the comments and interactions individuals receive on social media platforms in response to their posts. At present, feedback interventions are intended to increase the target behaviour frequency through social media positive reinforcement. Such reinforcement drives affective or cognitive engagement, which in turn can drive behavioural engagement. Several studies have used feedback intervention in social media to reduce food waste, and the BinCam app is a demonstration of just such a strategy (Comber et al., Citation2013). BinCam captures images of discarded items and shares them within the local resident community on Facebook. It utilises a visual representation of ‘leaves on a tree’ to showcase recycling accomplishments. The reduction of recyclable materials in the bin is visualised through the incremental growth of leaves on the tree, offering feedback to both individuals and the broader community. Despite these academic efforts, however, the effects of interventions using social media feedback have not been adequately assessed.

6. A framework for reducing food waste in tourism through social media intervention

Overall, the review revealed that examples of academics systematically designing, implementing and evaluating the role of social media intervention in food waste in tourism, are rare. To guide the future design of food waste intervention, the present study developed a framework for social media intervention research ().

6.1. Identifying food waste behaviours that can be targeted with social media intervention

The first step was to identify the targeted food waste behaviour. A major challenge in curbing tourist food waste using social media intervention is that food waste behaviours vary among tourists from a microscopic perspective. Food waste behaviours that impact tourists are diverse, such as the over-preparation of food before arrival, self-serving excessive quantities of food, the use of food for entertaining games during the trip, and the preparation of excessively bountiful food when entertaining friends. These behaviours can occur at various points along the behavioural chain, ranging from preparation, storage, consumption, and disposal. Among these behaviours, those tourist behaviours that significantly cause a large amount of food waste deserve more attention from researchers. In addition, it is important to recognise that not all of the behaviours can be effectively addressed through social media interventions.

For example, interventions targeting ‘over-ordering’ and ‘over-preparation’, are well-suited to social media awareness intervention. This approach can rapidly disseminate information, reaching a broad audience more cost-effectively than traditional interventions. The key challenge is how to track the effectiveness of these interventions for subsequent improvements. For such behaviour as, ‘over-selection of food’ at hotel buffets, however, social media interventions may not be the most suitable approach. This is because assessing the effectiveness of this type of intervention may require a longer time and involve significant feedback delays. In such cases, an on-site ‘nudge’ intervention might be more effective in at least reducing, if not preventing, over-selection of food. Social media is not a panacea for all unsatisfactory behaviours – identification of the links between the target behaviours and social media is a critical step in any social media intervention strategy.

6.2. Understanding key factors determine the behaviour

After identifying the target behaviours, the factors that trigger them should be investigated. To optimise the impact of behavioural interventions, it is vital to focus on the significant precursors of the relevant behaviour, and to remove obstacles to change. Thus, an understanding of the factors that influence food waste behaviour is crucial, and existing literature has identified a large number, including, personal taste (Filimonau & Delysia, Citation2019), over-cooking (Pirani & Arafat, Citation2016) and portion size (Kallbekken & Sælen, Citation2013). These efforts to identify factors that determine consumer food waste behaviour offer valuable insights into subsequent behavioural intervention studies. For instance, when using a social media intervention aimed at altering over-ordering behaviour by influencing tourists’ perceived peer pressure, it becomes crucial to assess whether the intervention actually did cause an increase in perceived peer pressure. This step is vital as it enables researchers to determine whether the intervention impact is attributable to the successful modification of perceived peer pressure. Identifying these factors can not only help researchers understand the mechanism of food waste, but also help practitioners allocate resources effectively in order to implement behavioural change strategies to solve the issue of food waste. Overall, this study encourages the exploration of factors that influence food waste in order to gain insights into how effective intervention mechanisms work.

6.3. Selecting the appropriate social media intervention mechanism

As social media interventions are likely to trigger specific behavioural change processes, any interventions adopted to reduce food waste need to be specific and targeted. On the one hand, this study summarised eight existing or potential social media interventions. Tailoring social media intervention mechanisms to specific contexts and behaviours is critical to the effectiveness of the intervention when changing food waste behaviours. For example, with the use of social support interventions that specialise in solving problems related to food storage and surplus management, members of online communities are able to share practical advice on how to effectively deal with leftovers. Social norms interventions are particularly suited to behaviours involving portion control, such as over-ordering and plate wastage, due to their social influence in encouraging responsible ordering and consumption. Platform nudge interventions excel at leveraging platform design and notification, and can gently guide users to make more prudent choices, thereby curbing over-ordering behaviour. Each intervention offers unique advantages, which, in order to optimise intervention effectiveness, need to be consistent with food waste behaviours and user preferences. On the other hand, several studies reviewed in this study used multiple interventions. As such, the effectiveness of a single intervention needs to be further examined.

6.4. Selecting the appropriate social media platform

After selecting the desired intervention mechanism, an important step (often overlooked by researchers), is to choose the appropriate social media platform. A review of previous literature revealed that most social media intervention studies tended to use either the Facebook or Twitter platform (Moreno & D'Angelo, Citation2019). Due to their large user base, social norms and social support are more easily implemented on these two platforms, than on other platforms, as social norms and support rely on the social influences generated by diverse and extensive social networks. The more users are present on these platforms, the greater the potential for individuals to be influenced by the behaviours, attitudes, and support of their peers. In contrast, TikTok has a young and engaged user base, a short-form content format, and interactive features, which make it a suitable platform for gamification intervention. Specifically, gamification tends to resonate well with younger users, who are accustomed to interactive and game-like experiences. An example is TikTok’s ‘Hashtag Challenge’ feature, which encourages users to participate in challenges. The largest short-video platform in China, Douyin, recently experienced a trend known as the ‘big stomach king challenge’, where users were encouraged to consume large amounts of food within a short period of time. In order to combat this potentially food-wasting activity, when users now search for keywords such as ‘eating broadcast’ or ‘big stomach king challenge’ on Douyin, they will see automatic prompts urging them to ‘reject food waste’ and eat reasonably (Li, Citation2020). (see Appendix A) shows an appropriate match between social media platforms for its potential intervention.

6.5. Evaluating the effectiveness of interventions

A systematic evaluation of social media interventions is crucial. When assessing the effectiveness of such interventions in reducing food waste, methods typically involve self-reporting of data, image recognition, analysis of food waste quantities, or weighing the actual amount of food wasted. Among these evaluation methods, the only approach that can offer reliable and accurate evidence around the effectiveness of interventions, is to physically weigh the food waste. However, previous studies using this method have been limited due to challenges such as restricted pathways for food waste collection, difficulties in waste categorisation, and limitations in waste collection methods. The process of weighing food waste is also associated with significant time and cost implications, presenting a series of practical challenges. While such approaches may be costly and time-consuming, they are crucial for accurately assessing the effectiveness of interventions, and there are now a range of smart approaches available to enhance the precision of measuring food waste. For targeted audiences, the provision of training on food waste collection and reporting, could be of practical use. They could also be equipped with toolkits, or user-friendly online applications dedicated to measuring and reporting food waste could be developed; approaches such as these could significantly enhance measurement efficiency. Moreover, to enhance effectiveness, it is crucial that the reasons behind unsuccessful interventions are uncovered, and accordingly, that the measures taken to enhance interventional effectiveness, be adjusted.

7. Research direction and future work

This research highlights the fact that social media intervention, and the strategies used to measure its effectiveness in reducing food waste, has been a persistent challenge due largely to flawed evaluation designs. The design and the sequential analysis of the effectiveness of social media intervention on food waste present promising research opportunities. First, previous measurements of the impacts of social media intervention have relied largely on a relatively short timeframe, and it is not clear whether the social media intervention developed, will have a long-term impact on people’s behaviour when it comes to reducing food waste. Longitudinal studies are more likely to offer insight into the long-term effect of social media interventions with respect to triggering behavioural changes, and to suggest strategies on how such behavioural change can be sustained.

Second, research opportunities exist for objectively measuring the food waste associated with social media interventions. Existing research on the reduction of food waste from various interventions has tended to rely on self-reported data when evaluating changes in food waste behaviour. While self-reported data can reflect this behaviour to a certain extent, many researchers have questioned its reliability, as food waste studies using self–reported data can suffer from social desirability bias. For example, using automated image analysis (e.g. an image of a rubbish bin taken at regular intervals), or on-site measurement, can provide more reliable and accurate evidence as to the effectiveness of an intervention. A range of factors needs to be considered when using field data to measure food waste, including, the duration of (prolonged) data collection periods, the potentially substantial economic costs, the limited avenues for food waste collection, and the challenge of accurately separating food from general waste.

Third, there is a wide range of social media interventions, and the effectiveness of these can differ. Future research is encouraged to examine the diverse range of strategies, and to identify the most effective combination for reducing food waste in tourism and hospitality. Relying on a single intervention (e.g. an awareness intervention) will have a limited and indirect impact on behavioural change, as behavioural change is more effectively influenced by a combination of multiple interventions and non-conscious factors, such as context, emotions, and habits. Therefore, incorporating a mix of interventions should result in a more impactful intervention. The effective combination of social media intervention with traditional interventional approaches in changing food waste behaviour, also presents promising avenues for future research.

Finally, current social media interventions and evaluations of their effectiveness, primarily focus on the individual level (tourists/residents). The reduction of food waste, however, can involve multiple stakeholders, including hotels, restaurants, food suppliers, and other industry interested parties, all of whom should be incorporated into the research. Businesses can reduce waste at various points in the food supply chain, from production to sales, and social media interventions targeting these businesses can lead to a greater impact that will extend far beyond the individual level.

8. Conclusion and limitation

Social media demonstrates the potential to trigger behavioural changes in a cost-effective manner (Al-Dmour et al., Citation2020; Hedin et al., Citation2019). The present study provides a novel social media intervention framework by detailing the antecedent (social norm, social support, and awareness), moderator (platform nudges, sharing, identity) and consequence (gamification, feedback) interventions that could be used to trigger behavioural changes and reduce food waste. Notably, present social media intervention research has predominantly focused on the antecedent level, being bound to motive, cause, and drivers. However, the reduction of food waste requires intervention at each stage. As such, the concept of social media intervention based on consequence is very promising. This review presents a small step in the large endeavour to reduce food waste in tourism and hospitality. From an academic standpoint, this review provides a comprehensive overview of the social media intervention literature relating to reducing food waste in tourism and hospitality. By delving into its theoretical mechanisms and primary themes, the study will assist researchers to position themselves within the existing literature when identifying novel intervention approaches. From a practical point of view, this review serves as an introduction to the rapidly evolving landscape of social media interventions and their relevance to sustainable tourism, addressing the call of Jenkins et al. (Citation2022) for an evidence-informed approach. By consolidating diverse and fragmented insights, it offers both individual tourists and service providers, holistic perspectives within their respective domains, enabling the effective formulation of strategies to reduce food waste. Furthermore, it sheds light on existing barriers and opportunities in reducing food waste, facilitating the harnessing of social media intervention benefits.

8.1. Theoretical implication

This research offers important theoretical contributions to extant tourism literature. First, it provides a comprehensive overview of academic approaches to reduce food waste in tourism and hospitality through the use of social media interventions. This holistic approach advances understanding of the multifaceted role of social media intervention in behavioural change, and provides the basis for subsequent discussion of the use of social media interventions to modify food waste behaviours; it also provides an evaluation of their effectiveness. Second, by applying a systematic and critical review, this study has proposed a novel framework in relation to social media interventions into antecedent, moderator, and consequence interventions. It has also outlined the intervention mechanism employed by current studies, thereby building on the existing knowledge base; this will assist researchers in identifying novel social media interventional approaches in tourism. This paper can serve as a reference to support further research when designing social media interventions. Third, the study contributes to the tourism and hospitality literature by identifying research gaps in the study of the use of social media intervention to reduce food waste, while recommending future research directions. These recommendations highlight significant emerging areas of research, as well as previously unexplored domains, particularly in terms of the long-term impacts of intervention, and the identification of effective combinations of social media interventions.

8.2. Practical implication

From the managerial perspective, the findings of this review are of immediate practical value to the tourism and hospitality industry, as they identify the practical social media interventions that have already been developed and tested to reduce food waste in tourism. Specifically, this review summarises several practical social media interventions to reduce food waste, and suggests strategies for implementation. Each one of those intervention measures can be immediately adopted by tourism and hospitality businesses to reduce food waste. Taking gamification intervention as an example, hotels and restaurants can introduce digital rewards such as badges, points, and leader boards in social media platforms to significantly enhance guest and media users engagement in food waste reduction activities. Media users earn rewards by participating in online campaigns for food waste reduction, which they can redeem for discounts on future bookings or complimentary meals. Integrating these gamification elements motivates users to contribute to sustainability efforts, further leading to a reduction in food waste. Another effective approach is the identity intervention through social media. Tourism and hospitality industry players could establish online communities on platforms such as Facebook, where users can showcase their efforts to reduce food waste and edit their own digital identities. Users who actively reduce food waste can earn virtual badges to display on their profiles. These identity badges highlight their commitment to sustainability and inspire others to adopt similar practices.

Although the effectiveness of social media interventions in reducing food waste has been empirically validated, food waste remains a complex economic, social, and cultural issue, and many other macro factors also influence waste behaviour. For example, studies of food waste outside of tourism have found that macro factors such as modernisation, industrialisation and economic growth have an impact on food waste (Joshi & Visvanathan, Citation2019; Thyberg & Tonjes, Citation2016). Retailers’ sales strategies, packaging strategies and date labelling strategies also have an impact on food waste behaviour (Wilson et al., Citation2017). The quality, appearance and presentation of the food itself can also influence food waste (Jaeger et al., Citation2018). The advantage of social media interventions lies in their ability to influence individual attitudes and behaviours, however, their impact on macro factors can be inherently limited. As Young et al. (Citation2017b) noted, social media is not the ‘silver bullet’ to reducing food waste. Nonetheless, social media presents an alternative and potentially more feasible approach to tackle the issue from the demand side by encouraging behavioural changes among consumers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Al-Dmour, H., Masa’deh, R. E., Salman, A., Abuhashesh, M., & Al-Dmour, R. (2020). Influence of social media platforms on public health protection against the COVID-19 pandemic via the mediating effects of public health awareness and behavioral changes: Integrated model. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e19996. https://doi.org/10.2196/19996

- Back, M. D., Stopfer, J. M., Vazire, S., Gaddis, S., Schmukle, S. C., Egloff, B., & Gosling, S. D. (2010). Facebook profiles reflect actual personality, not self-idealization. Psychological Science, 21(3), 372–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797609360756

- Beretta, C., & Hellweg, S. (2019). Potential environmental benefits from food waste prevention in the food service sector. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 147, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.03.023

- Bernstad, A. (2014). Household food waste separation behavior and the importance of convenience. Waste Management, 34(7), 1317–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2014.03.013

- Blundell, K.-L., & Forwood, S. (2021). Using a social media app, Instagram, to affect what undergraduate university students choose to eat. Appetite, 157, 104887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104887

- Chang, Y. Y.-C. (2022). All you can eat or all you can waste? Effects of alternate serving styles and inducements on food waste in buffet restaurants. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(5), 727–744. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1870939

- Chang, Y. Y. C., Lin, J.-H., & Hsiao, C.-H. (2022). Examining effective means to reduce food waste behaviour in buffet restaurants. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science, 29, 100554. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgfs.2022.100554

- Charry, K., & Tessitore, T. (2021). I tweet, they follow, you eat: Number of followers as nudge on social media to eat more healthily. Social Science & Medicine, 269, 113595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113595

- Choi, J., & Seo, S. (2017). Goodwill intended for whom? Examining factors influencing conspicuous prosocial behavior on social media. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 60, 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.09.014

- Chong, M., Leung, A. K.-Y., & Lua, V. (2022). A cross-country investigation of social image motivation and acceptance of lab-grown meat in Singapore and the United States. Appetite, 173, 105990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.105990

- Coary, S., & Poor, M. (2016). How consumer-generated images shape important consumption outcomes in the food domain. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 33(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2015-1337

- Comber, R., & Thieme, A. (2013). Designing beyond habit: Opening space for improved recycling and food waste behaviors through processes of persuasion, social influence and aversive affect. Personal and Ubiquitous Computing, 17(6), 1197–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00779-012-0587-1

- Comber, R., Thieme, A., Rafiev, A., Taylor, N., Krämer, N., & Olivier, P. (2013). BinCam: Designing for engagement with Facebook for behavior change. INTERACT 2013: 14th IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 2013. Springer, (pp. 99–115).

- Costa, I., Gill, P. R., Morda, R., & Ali, L. (2019). “More than a diet”: A qualitative investigation of young vegan Women's relationship to food. Appetite, 143, 104418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2019.104418

- Cugelman, B. (2013). Gamification: What it is and why it matters to digital health behavior change developers. JMIR Serious Games, 1(1), e3139. https://doi.org/10.2196/games.3139

- Davis, T., & Papies, E. K. (2022). Pleasure vs. identity: More eating simulation language in meat posts than plant-based posts on social media# foodtalk. Appetite, 175, 106024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106024

- Dhir, A., Talwar, S., Kaur, P., & Malibari, A. (2020). Food waste in hospitality and food services: A systematic literature review and framework development approach. Journal of Cleaner Production, 270, 122861. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122861

- Dolnicar, S. (2020). Designing for more environmentally friendly tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 84, 102933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102933

- Dolnicar, S., & Grün, B. (2009). Environmentally friendly behavior. Environment and Behavior, 41(5), 693–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508319448

- Dolnicar, S., & Juvan, E. (2019). Drivers of plate waste. Annals of Tourism Research, 78, 102731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.05.008

- Dolnicar, S., Juvan, E., & Grün, B. (2020). Reducing the plate waste of families at hotel buffets – a quasi-experimental field study. Tourism Management, 80, 104103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2020.104103

- Dolnicar, S., Knezevic Cvelbar, L., & Grün, B. (2017). Do pro-environmental appeals trigger pro-environmental behavior in hotel guests? Journal of Travel Research, 56(8), 988–997. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516678089

- Dolnicar, S., Knezevic Cvelbar, L., & Grün, B. (2019). A sharing-based approach to enticing tourists to behave more environmentally friendly. Journal of Travel Research, 58(2), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517746013

- Duong, C. T. P. (2020). Social media. A literature review. Journal of Media Research-Revista de Studii Media, 13, 112–126.

- Farrow, K., Grolleau, G., & Ibanez, L. (2017). Social norms and pro-environmental behavior: A review of the evidence. Ecological Economics, 140, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.04.017

- Filimonau, V., & Delysia, A. (2019). Food waste management in hospitality operations: A critical review. Tourism Management, 71, 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.10.009

- Filimonau, V., Nghiem, V. N., & Wang, L. (2021). Food waste management in ethnic food restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 92, 102731. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102731

- Freedman, M. R., & Brochado, C. (2010). Reducing portion size reduces food intake and plate waste. Obesity, 18(9), 1864–1866. https://doi.org/10.1038/oby.2009.480

- Gimpel, H., Heger, S., Olenberger, C., & Utz, L. (2021). The effectiveness of social norms in fighting fake news on social media. Journal of Management Information Systems, 38(1), 196–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2021.1870389

- Grainger, M. J., & Stewart, G. B. (2017). The jury is still out on social media as a tool for reducing food waste a response to Young et al. (2017). Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 122, 407–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.04.001

- Guenther, L., Schleberger, S., & Pischke, C. R. (2021). Effectiveness of social media-based interventions for the promotion of physical activity: Scoping review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413018

- Guidry, J. P., Miller, C. A., Hayes, R., Ksinan, A. J., Carlyle, K. E., & Fuemmeler, B. F. (2023). Reading, sharing, creating Pinterest recipes: Parental engagement and feeding behaviors. Appetite, 180, 106287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106287

- Hales, S. B., Davidson, C., & Turner-Mcgrievy, G. M. (2014). Varying social media post types differentially impacts engagement in a behavioral weight loss intervention. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 4(4), 355–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13142-014-0274-z

- Hedin, B., Katzeff, C., Eriksson, E., & Pargman, D. (2019). A systematic review of digital behaviour change interventions for more sustainable food consumption. Sustainability, 11(9), 2638. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092638

- Henderson, J. C. (2009). Food tourism reviewed. British Food Journal, 111(4), 317–326. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700910951470

- Hsu, M. S., Rouf, A., & Allman-Farinelli, M. (2018). Effectiveness and behavioral mechanisms of social media interventions for positive nutrition behaviors in adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health, 63(5), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.06.009

- Hunter, R. F., De la Haye, K., Murray, J. M., Badham, J., Valente, T. W., Clarke, M., & Kee, F. (2019). Social network interventions for health behaviours and outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Medicine, 16(9), e1002890. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002890

- Jaeger, S. R., Machín, L., Aschemann-Witzel, J., Antúnez, L., Harker, F. R., & Ares, G. (2018). Buy, eat or discard? A case study with apples to explore fruit quality perception and food waste. Food Quality and Preference, 69, 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2018.05.004

- Jenkins, E. L., Brennan, L., Molenaar, A., & Mccaffrey, T. A. (2022). Exploring the application of social media in food waste campaigns and interventions: A systematic scoping review of the academic and grey literature. Journal of Cleaner Production, 360, 132068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132068

- Joshi, P., & Visvanathan, C. (2019). Sustainable management practices of food waste in Asia: Technological and policy drivers. Journal of Environmental Management, 247, 538–550. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.06.079

- Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude-behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.05.012

- Juvan, E., Grün, B., & Dolnicar, S. (2018). Biting off more than they can chew: Food waste at hotel breakfast buffets. Journal of Travel Research, 57(2), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516688321

- Kaakinen, M., Sirola, A., Savolainen, I., & Oksanen, A. (2020). Shared identity and shared information in social media: Development and validation of the identity bubble reinforcement scale. Media Psychology, 23(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2018.1544910

- Kallbekken, S., & Sælen, H. (2013). ‘Nudging’ hotel guests to reduce food waste as a win–win environmental measure. Economics Letters, 119(3), 325–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.03.019

- Kay, E., Kemps, E., Prichard, I., & Tiggemann, M. (2023). Instagram-based priming to nudge drink choices: Subtlety is not the answer. Appetite, 180, 106337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106337

- Kim, Y. G., & Eves, A. (2012). Construction and validation of a scale to measure tourist motivation to consume local food. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1458–1467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.01.015

- Kuo, C., & Shih, Y. (2016). Gender differences in the effects of education and coercion on reducing buffet plate waste. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 19(3), 223–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/15378020.2016.1175896

- Laranjo, L. (2016). Social media and health behavior change. In S. Syed-Abdul, E. Gabarron, & A.Y.S Lau (Eds.), Participatory health through social Media (pp. 83–111). Academic Press.

- Laranjo, L., Arguel, A., Neves, A. L., Gallagher, A. M., Kaplan, R., Mortimer, N., Mendes, G. A., & Lau, A. Y. (2015). The influence of social networking sites on health behavior change: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 22(1), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1136/amiajnl-2014-002841

- Laurenceau, J.-P., Barrett, L. F., & Pietromonaco, P. R. (1998). Intimacy as an interpersonal process: The importance of self-disclosure, partner disclosure, and perceived partner responsiveness in interpersonal exchanges. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1238. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1238

- Lazell, J. (2016). Consumer food waste behaviour in universities: Sharing as a means of prevention. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 15(5), 430–439. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1581

- Lehdonvirta, V., & Räsänen, P. (2011). How do young people identify with online and offline peer groups? A comparison between UK, Spain and Japan. Journal of Youth Studies, 14(1), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2010.506530

- Li, B. G. P. (2020). China cracks down on ‘shameful’ food waste as craze for online overeating challenges soars [Online]. Available: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/china-food-waste-douyin-tiktok-challenge-xi-jinping-a9668491.html [Accessed]

- Li, N., & Wang, J. (2020). Food waste of Chinese cruise passengers. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(11), 1825–1840. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1762621

- Lim, V., Funk, M., Marcenaro, L., Regazzoni, C., & Rauterberg, M. (2017). Designing for action: An evaluation of Social Recipes in reducing food waste. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 100, 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2016.12.005

- Liu, T., Juvan, E., Qiu, H., & Dolnicar, S. (2022). Context- and culture-dependent behaviors for the greater good: A comparative analysis of plate waste generation. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(6), 1200–1218. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1918132

- Lodes, A. (2019). Social media campaign and food waste challenge raises awareness and reduces food waste in the home. Creative Components, 330.

- Macinnes, S., Grün, B., & Dolnicar, S. (2022). Habit drives sustainable tourist behaviour. Annals of Tourism Research, 92, 103329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103329

- Maher, C., Ferguson, M., Vandelanotte, C., Plotnikoff, R., De Bourdeaudhuij, I., Thomas, S., Nelson-Field, K., & Olds, T. (2015). A web-based, social networking physical activity intervention for insufficiently active adults delivered via Facebook app: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(7), e174. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.4086

- Martin, C. J. (2016). The sharing economy: A pathway to sustainability or a nightmarish form of neoliberal capitalism? Ecological Economics, 121, 149–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.027

- Mazzucchelli, A., Gurioli, M., Graziano, D., Quacquarelli, B., & Aouina-mejri, C. (2021). How to fight against food waste in the digital era: Key factors for a successful food sharing platform. Journal of Business Research, 124, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.055

- Mikal, J. P., Rice, R. E., Kent, R. G., & Uchino, B. N. (2016). 100 million strong: A case study of group identification and deindividuation on Imgur.com. New Media & Society, 18(11), 2485–2506. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815588766

- Moreno, M. A., & D'Angelo, J. (2019). Social media intervention design: Applying an affordances framework. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(3), e11014. https://doi.org/10.2196/11014

- Moreno, M. A., & Whitehill, J. M. (2014). Influence of social media on alcohol use in adolescents and young adults. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews, 36, 91.

- Murphy, J., Gretzel, U., Pesonen, J., Elorinne, A.-L., & Silvennoinen, K. (2018). Household food waste, tourism and social media: A research agenda. Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2018: Proceedings of the International Conference in Jönköping, Sweden, January 24–26, 2018, Springer, (pp. 228–239).

- Naslund, J. A., Kim, S. J., Aschbrenner, K. A., Mcculloch, L. J., Brunette, M. F., Dallery, J., Bartels, S. J., & Marsch, L. A. (2017). Systematic review of social media interventions for smoking cessation. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.002

- Nisa, C., Varum, C., & Botelho, A. (2017). Promoting sustainable hotel guest behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 58(4), 354–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1938965517704371

- Okumus, B., Taheri, B., Giritlioglu, I., & Gannon, M. J. (2020). Tackling food waste in all-inclusive resort hotels. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 88, 102543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102543

- Papargyropoulou, E., Wright, N., Lozano, R., Steinberger, J., Padfield, R., & Ujang, Z. (2016). Conceptual framework for the study of food waste generation and prevention in the hospitality sector. Waste Management, 49, 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2016.01.017

- Pirani, S. I., & Arafat, H. A. (2016). Reduction of food waste generation in the hospitality industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 132, 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.146

- Pop, R.-A., Săplăcan, Z., & Alt, M.-A. (2020). Social media goes green—The impact of social media on green cosmetics purchase motivation and intention. Information, 11(9), 447. https://doi.org/10.3390/info11090447

- Qutteina, Y., Hallez, L., Mennes, N., De Backer, C., & Smits, T. (2019). What do adolescents see on social media? A diary study of food marketing images on social media. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2637. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02637

- Shawky, S., Kubacki, K., Dietrich, T., & Weaven, S. (2019). Using social media to create engagement: A social marketing review. Journal of Social Marketing, 9(2), 204–224. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSOCM-05-2018-0046

- Simeone, M., & Scarpato, D. (2020). Sustainable consumption: How does social media affect food choices? Journal of Cleaner Production, 277, 124036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124036

- Stöckli, S., Niklaus, E., & Dorn, M. (2018). Call for testing interventions to prevent consumer food waste. Resources, conservation and recycling, 136, 445–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.03.029

- Sundt, P. (2012). Prevention of food waste in restaurants, hotels, canteens and catering. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin.

- Thyberg, K. L., & Tonjes, D. J. (2016). Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 106, 110–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.11.016

- Wang, G., Zhang, W., & Zeng, R. (2019). WeChat use intensity and social support: The moderating effect of motivators for WeChat use. Computers in Human Behavior, 91, 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.010

- Welch, V., Petkovic, J., Simeon, R., Presseau, J., Gagnon, D., Hossain, A., Pardo, J. P., Pottie, K., Rader, T., & Sokolovski, A. (2018). Interactive social media interventions for health behaviour change, health outcomes, and health equity in the adult population. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2018(2), 12932.

- Wilson, N. L., Rickard, B. J., Saputo, R., & Ho, S. T. (2017). Food waste: The role of date labels, package size, and product category. Food Quality and Preference, 55, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodqual.2016.08.004

- Wohlin, C., Mendes, E., Felizardo, K. R., & Kalinowski, M. (2020). Guidelines for the search strategy to update systematic literature reviews in software engineering. Information and software technology, 127, 106366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infsof.2020.106366

- Young, C. W., Russell, S. V., & Barkemeyer, R. (2017b). Social media is not the ‘silver bullet’ to reducing household food waste, a response to Grainger and Stewart (2017). Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 122, 405–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2017.04.002

- Young, W., Russell, S. V., Robinson, C. A., & Barkemeyer, R. (2017a). Can social media be a tool for reducing consumers’ food waste? A behaviour change experiment by a UK retailer. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 117, 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2016.10.016

- Zhu, O. Y., Li, H., Grün, B., & Dolnicar, S. (2024). The power of respect for authority and empathy – Leveraging non-cognitive theoretical constructs to trigger environmentally sustainable tourist behaviour. Annals of Tourism Research, 105, 103681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2023.103681

Appendix A

Table A1. Appropriate social media platforms for potential intervention