Abstract

Cancer is a common condition of the older male. Risk factors for developing a malignancy include genetic, environmental and life style features. Cancer epidemiology and prognosis differ depending on the age and gender of the population being studied. In the group of men older than 65 years, the most common malignant tumors are prostate, lung, colon and pancreatic cancer. Treatment options vary depending on the stage of the tumor when it is diagnosed, and the decision for therapeutic versus palliative interventions will depend upon the functional status, comorbidity and personal wishes of the patients.

Introduction

An unavoidable consequence of aging is the increased risk of cancer. As the proportion of elderly persons has increased in most countries during the last few decades, and will increase further in the coming years, the incidence of cancer is expected to increase Citation[1]. Cancer is a very common disease of the older adult and is associated with a high index of mortality and disability Citation[1]. Cancer is the most common cause of death in persons over 60 years of age, and the second most common cause of death in persons over 80 years of age.

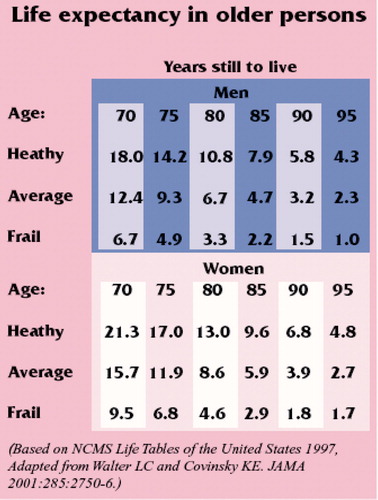

The medical literature and epidemiologic data typically characterize the population as older than or younger than 65 years. Some studies, however, label patients as ‘older’ when they are >75 years, and further categorize those patients >85 years as the oldest-oldCitation[2-4]. The proportion of persons over 65 years has increased from around 5% to over 20% in some West European countries during the last few decades. It is estimated that in the next century around 25% of the population in many countries will be older than 65 years Citation[5]. Healthy men who reach the age of 70 are expected to live an additional 18 years. Those who reach the age of 85 can expect to live an additional 8 years ().

The steadily increasing number of elderly patients with cancer is becoming a global health concern, especially for industrialized countries with a higher percentage of the population over the age of 65.

In these developed nations:

the risk of cancer increases with age;

the effectiveness of anticancer treatments has taken many cancers to a state of a ‘chronic disease’; and

mortality from cardiovascular conditions, the leading cause of death, is decreasing Citation[6].

The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has calculated the incidence rates of cancer per 100,000 elderly persons based on data from cancer registries in 51 countries across five continents. The overall incidence of any cancer in elderly men is 61%. The frequency of any cancer, except non-melanoma skin cancer, is almost sevenfold more among elderly men (2,158 per 100,000 person–years), and fourfold more among elderly women (1,192 per 1,000,000 person–years) than among younger persons (30–64 years old) Citation[9].

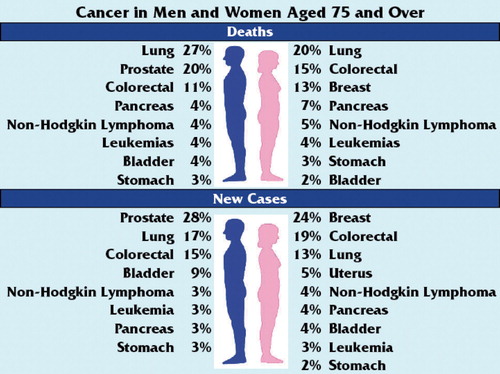

The incidence of cancer is higher in men than in women, and this difference is most evident after 64 years of age. There is a sharp incident rise in cancer after the age of 64 for both men and women, but is higher for men (559.6 per 100,000 men vs 420.1 per 100,000 women). Among elderly men, the three most frequent cancers account for 50% of all malignancies (prostate, lung and colon) (). Lung cancer is the most common malignant entity in both men and women over the age of 60 and is responsible for 30% of all cancer deaths in this group. The second highest incidence cancers are breast and colorectal cancer for women, and colorectal and prostate cancer for men Citation[10].

Carcinogenesis in the elderly

Cancers demonstrate varying degrees of aggressiveness. Some are relatively benign, such as skin cancers, which often grow at a very slow rate. Other cancers remain localized to the primary organ for long periods of time before spreading through the lymphatic system. In general, the most common mechanism for spread of malignant tumors is through the lymph vessels and nodes or blood stream, causing metastases to distant organs.

The incidence of some malignant conditions such as brain tumors and skin cancer has increased in older persons for the last 30 years. Although the reasons for this increase are not totally clear, it is believed that age-related molecular alterations increase the likelihood of susceptibility to environmental carcinogens Citation[11].

There are many other reasons why cancer is more common in older adults. First, the elderly have had a more prolonged exposure to chemical and environmental carcinogens. Cell injury may develop from accumulation of agents and byproducts of normal cell physiological activity, such as superoxide, hydrogen peroxide, nitrous oxide and hydroxyl radicals. Consequently, activation of genes that promote cell replication or suppress cell quiescence in response to endogenous or exogenous irritants has been demonstrated in ingenious gene-activity mapping studies Citation[10]. A multistage carcinogenic process is dependent on the duration and intensity of exposure to initiators (e.g. toxins, infectious agents, radiation, hereditary genetic makeup of cells) and promoters (favor the growth of transformed cells) Citation[11].

Aging itself also alters the biology of cancer by affecting tumor activity and the response to treatment Citation[12]. As a general rule, most tumors differ in terms of a growth pattern, doubling time, hormonal receptor status, DNA ploidy, angiogenesis, percentage of cells in S-phase, P53 expression and extracellular matrix proteins expression Citation[13]. Senescent tissues in general may also provide a microenvironment that is less capable of supporting rapid tumor growth and handling the accumulation of byproducts of normal cell physiological activity. Thus, histologically identical tumors in older patients are likely to be different than those in younger patients Citation[14].

With aging there is a decline in the body's immune system. The ability of natural killer cells to destroy cancer cells before they can accumulate is reduced Citation[13]. In individual cells, the main regulator of division is located at the telomere at the end of each chromosome. With each cell division, telomeres get shorter and thus decrease the ability of a cell to control the rate of cell division. Uncontrolled cell division thus increases the likelihood of DNA errors. It is also now apparent that the ability of cells to self-repair may be affected by senescence Citation[14].

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) in patients with cancer

Many forms of geriatric assessment exist, although some of them are too time intensive to be applied broadly to all geriatric patients. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends that all patients older than 70 years be screened using some form of geriatric assessment. The consensus panel recommends that an evaluation must address at a minimum the following areas Citation[15],Citation[16]:

Functional status

Comorbidity

Socioeconomic issues

Nutritional status

Polypharmacy

Geriatric syndromes

Quality of life

Palliative care (advanced directives)

Pain

Elder abuse

Dependence in one or more instrumental activities of daily living such as inability to go shopping, use transportation or use the telephone, is associated with reduced tolerance to chemotherapy and a higher risk of developing complications from cytotoxic agents. However, if quality of life is the focus, frail individuals can still benefit from chemotherapy using drugs with lower rates of complications such as taxanes, gemcitabine or navelbine.

Because the direct or indirect effects of cancer have a significant impact on overall health, it is important to evaluate functional status in older cancer patients. Functional status evaluation can provide important baseline information for later camparison if health status changes during cancer care. Functional status can also assist medical providers in selecting appropriate rehabilitation methods, predicting clinical outcomes, selecting cancer therapies and monitoring the effects of cancer therapies. A variety of functional status evaluation tools have been developed and used in the care of older cancer patients.

Medical complications of malignancy in the elderly

Neoplastic diseases can precipitate other acute and chronic medical conditions. These may develop due to the natural progression of the malignancy itself or as a result of pharmacologic or surgical interventions performed in treating the specific tumor.

Spinal cord compression is an oncological emergency, with presenting symptoms shared by all primary tumors. Any patient who develops pain along the spinal axis with or without a radicular pattern, loss of sphincter control, gait abnormalities or paraplegia needs to be thoroughly evaluated and treated immediately with intravenous corticosteroids or radiation therapy for radiorensponsive tumors. Surgical decompression with laminectomy is another option for malignancies of unknown tumor type, a previous history of high dose spinal radiation or failure to respond to radiation therapy.

In rare cases, patients may present with hemoptysis due to a previously undiagnosed pulmonary neoplasm. Tumor erosion into a major blood vessel is usually a late sign and requires emergent treatment if the hemoptysis is massive (up to 5dl–6dl). Medical interventions (airway, breathing and circulation should be secured) and sometimes surgical procedures to control the bleeding are necessary.

Metabolic and electrolyte abnormalities are common complications of certain hematologic and skeletal tumors. Hypercalcemia is seen with body metastasis and commonly manifests with apathy, depression, somnolence, delirium, personality change, polyuria and constipation. Glucocorticoids can be useful in the management of hypercalcemia caused by lymphoma, myeloma and breast cancer. Salmon calcitonin has also been useful in controlling hypercalcemia in some patients. Biophosphonates such as pamidronate and zolendronate have greatly improved the management of hypercalcemia of cancer Citation[17].

Other metabolic abnormalities, such as hyponatremia, are of particular importance in the elderly, since these alterations can lead to rapid cognitive deterioration, brain edema and seizures. Hyponatremia from the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH) is most frequently seen with small cell undifferentiated carcinoma of the lung and central nervous system tumors or metastases.

Fractures of weight-bearing bones are common in the elderly with osteopenia. This complication occurs in patients with metastatic disease to bone or in those receiving treatment for malignancies that reduce bone density and quality. Progressive pain is a cardinal symptom, along with functional decline before the fracture occurs. Prophylactic surgery or focal radiation therapy are treatment options for areas of bony destruction.

Amnesia, changes in mood or personality, delirium, dementia or seizures can indicate metastases, paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis or primary tumor invasion of the brain. Malignancy-induced metabolic or electrolyte abnormalities may also cause neurologic symptoms such as ataxia, visual changes or neuropathy.

Anemia is a common disorder in the elderly population, and is an independent predictor for increased 5-year morbidity and mortality, even after adjustment for comorbid malignant neoplasms and other chronic medical conditions. Older patients with anemia have a higher likelihood of physical decline, disability, hospital admission and institutionalization. Anemia leads to functional impairment, and is a risk factor for falls in older individuals. Anemia is also associated with decreased muscle density and strength. If anemia produces a high level of fatigue, quality of life can be significantly impaired in individuals with malignancies Citation[18],Citation[19].

Testosterone levels decline with aging. Diagnosing true symptomatic hypogondism can be difficult, because many symptoms of hypogondism are similar to age-related physiologic changes in older males. Testosterone replacement may alleviate the symptoms of hypogondism, improve sexual functioning, and improve functional outcomes during rehabilitation. Overall improvement in well-being and/or health-related quality of life in older males is more difficult to demonstrate with testosterone replacement therapy.

Specific cancers

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is a major public health concern as it is becoming one of the most common cancers in males, affecting one in six men in developed countries. Prostate cancer is the malignant tumor with the highest incidence among older men Citation[20] ().

The development of prostate cancer is age-related and is uncommon before the age of 50. After this age, the incidence and mortality rates increase exponentially. Approximately half of all men aged >80 years may have non-clinically apparent prostate cancer. Since many, but not all, cancers registries include diagnoses from autopsy examination of patients who died from other causes, and in whom cancer was not initially diagnosed, the prevalence of prostate cancer may be underestimated Citation[21].

The extended practice of careful histological examination of tissue removed by prostatectomy for benign prostatic hypertrophy has long been known to identify small asymptomatic cancers Citation[22],Citation[23]. Furthermore, after the introduction of screening with prostate-specific antigen (PSA) in 1986, there have been dramatic changes in the epidemiology of this disease, leading to an apparent increase in the incidence of prostatic cancer, especially for localized stages Citation[24].

In the current era of widespread PSA testing, approximately 75% of all prostate cancer cases are detected early as a result of abnormal PSA findings. In contrast, the majority of cases presenting with lymph node involvement, indicative of advanced disease, has decreased considerably. It is now estimated that more than 67% of men are diagnosed with localized and early tumors. Thirty per cent of these patients with apparently local disease, treated with radical prostatectomy, will relapse biochemically within 5 years Citation[25].

The incidence of prostate cancer varies worldwide, with the highest rates found in the United States, Canada and Scandinavia, and the lower rates found in China and other parts of Asia Citation[21],Citation[26]. The number of men over the age of 65 years is expected to increase worldwide from 12.4% in 2000 to 19.6% in 2030. This trend will be accompanied by a substantial increase in the number of men who will be diagnosed with prostate cancer requiring treatment Citation[27],Citation[28]

The increase in male life expectancy has also contributed to a rising number of elderly men who face prolonged and multidimensional treatment regimens for prostate cancer Citation[29]. Patients with prostate cancer are often provided a choice of treatments including observation (watchful waiting), hormonal therapy, radical prostatectomy, external beam or interstitial radiation and cryoablation.

Current treatment guidelines for localized prostate carcinoma recommend potentially curative therapy for patients whose remaining life expectancy is 10 years or more. Patients with limited life expectancy are more likely to die of unrelated causes, whereas those who survive beyond 10 years are at higher risk of death from progressive prostate carcinoma Citation[30],Citation[31]. The 10-year rule is broadly accepted among urologists and radiation oncologists Citation[32],Citation[33].

Lung cancer

More than 50% of all lung cancers are diagnosed in patients aged 65 years or older, with more than 30% occurring in those over 70 years. Lung cancer is the most deadly malignancy in men and women in the United States. Because surgical risk increases over the age of 65, procedures for lung cancer are less frequently performed in elderly patients Citation[34].

Lung cancer among elderly men is less frequent than prostate cancer, but is expected to increase as individuals who smoke grow older and have longer periods of exposure time to the deleterious effects of tobacco. Lung cancer is not uncommon among persons older than 85 Citation[34]. Over the past few decades, the lung cancer rate has declined among men, but has steadily and substantially increased among elderly women, as a result of gender changes in tobacco-smoking pattern Citation[35].

At the beginning of the twentieth century, if an American woman smoked a cigarette it was considered disgraceful behavior. Some localities even enacted laws to prohibit women from smoking in public. It was not until the 1920s and 1930s that female leaders in society, often debutantes and college women, were allowed to smoke in public. By the 1960s, over 30% of the female population smoked. Many thought that women were not susceptible to smoking-related illnesses, like lung cancer, that were seen in men. In 1987, the death rate from lung cancer in women surpassed that of breast cancer. Since 1987, the lung cancer death rate has been steadily rising.

In women, adenocarcinoma accounts for the majority of lung carcinoma, making the diagnosis more difficult and challenging, since most of these tumors are located in the lung periphery with just minor or no symptoms. Women have also been found to have better prognosis and lower surgical mortality than men, independent of the effects of age, symptoms, smoking habits, type of surgery, histology and stage of the disease. The reason for such a gender difference remains elusive, and indeed, this is only true for the early tumour stages. The presence of estrogen receptors has been demonstrated on human lung cancer tissue, which suggests a possible link between better prognosis in lung carcinoma and hormonal status.

Among newly diagnosed cases of lung cancer (bronchogenic carcinoma), more than 80% are non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLC): squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma. The most common type of lung cancer is adenocarcinoma, which is more likely to have metastasized at the time of presentation.

Three quarters of patients with adenocarcinoma present with Stage III or IV disease. Squamous cell type usually presents in earlier IA-IB stages () Citation[36]. Some physicians thus recommend more aggressive radiographic staging for adenocarcinoma.

Table I. Lung cancer staging.

The remaining 20% of lung malignancies are small cell lung cancer (SCLC) and present in an advanced stage in more than half of the cases. The incidence of SCLC has fallen with increasing age, whereas that of squamous cell carcinoma has risen. Other rare primary lung tumors include bronchial gland tumors, carcinoid tumors and vascular sarcomas Citation[35].

Lung cancer is commonly diagnosed incidentally by radiography performed for an unrelated indication. However, many cases present with warning symptoms, such as chest-wall pain, hemoptysis, shortness of breath, pleural effusion, atelectasis or systemic complaints such as weight loss or night sweats Citation[37].Citation[38]. The benefit of screening, especially in individuals with a long smoking history, seems intuitive, but given the high prevalence of smokers, screening represents a major healthcare expenditure. There are currently no universal recommendations for lung cancer screening in any age group. This is, in part, because there have been no definite data demonstrating decreased mortality with screening Citation[39],Citation[40].

The healthcare team treating elderly patients with lung cancer is often faced with difficult decisions. Clinically evident lung cancer is not indolent; therefore, there is greater need to offer treatment to the patient with lung cancer than with some other malignancies. Second, the morbidity associated with treatment can be significant. Based on the results of multiple, large patient data series such as the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC), it is known that age alone is not a significant prognostic factor in increased morbidity and mortality. It is more important to assess physiologic state and functional capacity rather than chronological age when selecting treatment options.

The benefits of a CGA in older adults with lung cancer include identifying potential candidates for treatment, estimating life expectancy, assessing treatment tolerance and identifying reversible conditions that may interfere with cancer treatment if left unattended Citation[41]. It is important to identify those unusually healthy older persons who may tolerate aggressive treatments and those frail individuals who may not.

Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for patients with Stages I to III NSCLC. In the older patient, decisions regarding surgical treatment must involve an assessment of the patient's functional status and life expectancy Citation[39]. Curative resection is still feasible in older adults. In a study of octogenarian patients undergoing curative treatment for lung cancer (standard lobectomy), the complication rate was: 3.7% perioperative death, 11% major complications and 42% non-fatal complications. Survival rates were 86% at one year, 62% at three years and 43% at five years for patients classified as Stage I Citation[42],Citation[43].

Multiple chemotherapy agents have been shown to have activity in SCLC and NSCLC. The use of chemotherapy in the elderly NSCLC population is complicated by age-related issues of reduced organ function and higher prevalence of comorbid disorders that affect treatment decisions. At present, single-agent chemotherapy appears to be a reasonable choice in elderly patients with advanced NSCLC. This conclusion arises from the efficacy and tolerability observed with vinorelbine and gemcitabine as single agents in both phase II and III trials Citation[44],Citation[45]. Chemotherapy is also applied in combination with radiation therapy for locally advanced disease. This is also the standard management for Stage IV disease, where it may improve survival and quality of life.

Colorectal cancer

Colorectal cancer is the second leading cause of cancer in most developed countries and accounts for 13% of all cancer deaths. In men, colorectal cancer ranks third in frequency after lung and prostate cancers. The incidence rate is similar among men and women of equivalent age until 50 years, after which it becomes slightly higher in men than in women, and then, after the age of 85, it is essentially the only cancer that occurs with approximately equal frequency in men and women. Colorectal cancer accounts for 30% of all cancers Citation[46]. One quarter of patients have advanced or metastatic disease at diagnosis and one half of all patients die of their disease.

Old age is the single greatest risk factor for developing colon cancer, with a median age of 71 years at diagnosis. The incidence rises continuously from adulthood through the ninth decade of life Citation[46], in part because of the time required for polyps to undergo transformation from normal to malignant tissue.

Colorectal cancer mortality can be reduced by screening all men and women aged 50 years or older. In fact, between 1985 and 1995, a 1.8% per year decline in mortality was observed for both men and women Citation[47]. Moreover, increasing numbers of colon cancer patients are now survivors, with an annual decline in mortality rate of 1.7% over the past 15 years Citation[48].

Several tests are available for colon cancer screening, including fecal occult blood testing (FOBT), flexible sigmoidoscopy, double-contrast barium enema and colonoscopy. Current evidence has shown that all these tests are effective, with some differences in their sensitivity, specificity, cost and safety. Other colorectal cancer tests, such as virtual colonoscopy or stool-based molecular testing, have the potential to become important screening tests in the future Citation[49].

In high risk populations, older men are more likely to develop left-sided colon cancer and rectal cancer, and older women are more likely to develop right-sided colon cancer; however, men have higher prevalence of colon polyps and tumors overall, and women have higher prevalence of pure right-sided polyps and tumors. Men are more likely to be diagnosed with colon cancer at an earlier stage, especially carcinoma in situ, leading to a better prognosis, probably because men are more likely than women to be screened for colon cancer.

Radical surgery remains the most effective treatment for colorectal malignancies, but given the high morbidity, fewer elderly patients actually receive major surgery than their younger counterparts Citation[50]. The recognition that comorbidity, not age, is the more reliable predictor of operative risk has led to a greater willingness to attempt curative resection. The use of comprehensive geriatric assessment can help to subdivide the population into three groups for whom colon cancer treatment approaches are suggested Citation[52].

Group 1: Functionally independent patients who have no serious comorbidities should be treated with a combination of infusional fluorouracil/calcium folinate and irinotecan (or oxiplatin if secondary resection of liver metastasis is an option). Elderly patients have a reduced tolerance to 5-flourouracil (5-FU); therefore, a dose reduction is sometimes advisable, particularly when creatinine clearance is reduced. Mucositis (small bowel and oral cavity) is a common side effect, but it can be avoided by means of prophylactic medications like folic acid/levamisole Citation[51],Citation[52].

Group 2: Treatment decisions for patients who are dependent in one or more instrumental activities are more challenging. This is the most heterogeneous group and data on treatment outcomes are almost non-existent. If the average life expectancy is likely to exceed tumor-specific median survival, monotherapy with infusional fluorouracil/calcium folinate as first-line and irinotecan as second-line treatment might be instituted.

Group 3: Frail patients, defined by dependence in one or more activities of daily living, having three or more comorbid conditions or one or more geriatric syndromes should be treated with supportive care. Cytotoxic therapy should be considered only if a palliative effect is expected.

The role of radiotherapy in the treatment of colorectal cancer continues to be studied, and it appears that current practice of radiotherapy for inoperable tumors may evolve to include other multimodal therapies. Postoperative radiation therapy is used as part of a multi-interventional approach to prevent local–regional recurrence.

Pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death among men. Although the spectrum of malignant pancreatic neoplasms includes islet cell tumors, cystadenocarcinomas and other rare neoplasms, adenocarcinoma of ductal origin represents about 90% of pancreatic cancers Citation[53].

An increased incidence of pancreatic cancer is seen in those patients who are male, of advanced age and black race. The overall risk of pancreatic cancer is low during the first three to four decades of life, but increases sharply after the age of 50 years, with a peak incidence in the seventh and eighth decades. The age-adjusted death rate of pancreatic cancer has been shown to be higher in males, approximately 1.7-fold higher than in females; hormonal factors related to pancreatic cancer in females have been observed by analysis of menarche, menopause and reproductive history.

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer are not quiet clear, but it seems to be associated with smoking and chronic pancreatitis. The effect of caffeine consumption is questionable and the data does not support any specific risk from an occupational exposure. There are a few genetic changes that are commonly seen in pancreatic cancers, with mutations in the oncogene K-ras being the most common (80–90% of cases) Citation[53].

The clinical features of pancreatic cancer are initially non-specific, and contribute to a delay in diagnosis of about eight weeks. Truly painless jaundice is unusual but weight loss, abdominal pain and back pain are typical presenting symptoms. Glucose intolerance, while uncommon, may develop 6 to 12 months prior to the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. The onset of glucose intolerance in an elderly patient with vague gastrointestinal symptoms should alert the clinician to the possibility of pancreatic cancer. Physical examination often indicates few signs on presentation, with the exception of those patients presenting with obstructive jaundice. Courvoisier's sign, which is the classical palpable gallbladder, actually occurs in very few patients.

A wide variety of tumor-associated antigens have been evaluated as markers for screening and diagnosing pancreatic cancer. A CA-19-9 level of >37 UI/ml (sensitivity 85%, specificity 85%) has been the most useful in clinical practice Citation[54]. Increased levels of CA 19-9 following operative resection have been shown to correlate with poor survival, and may be useful in selecting appropriate patients for a more aggressive adjuvant therapy program.

Initially, if pancreatic cancer is suspected, an enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is necessary to confirm the diagnosis. A biopsy confirmation of the lesion is of paramount importance, because a number of tumors other than adenocarcinoma, such as islet cell carcinoma and lymphoma, may be diagnosed. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is very helpful in delineating the exact site of obstruction and may be used to obtain exfoliative ‘brush’ cytology. ERCP may not be necessary when non-invasive methods have established the diagnosis and stage. Pancreatic cancer is typically staged using a tumor size, nodes and metastasis (TNM) staging system.

Curative treatment is only possible for a minority of patients with resectable disease at presentation. The most common surgical intervention is a pancreaticoduodenectomy, or Whipple's procedure, but even for small lesions the recurrence rate is 80%. Results from available studies have shown that long-term survival after resection in elderly patients is poor, and also the rate of complications is higher than in any other age group. A critical evaluation is necessary to decide whether the elderly patient can tolerate a radical pancreatic resection. Palliative interventions such as biliary tract decompression with endoscopic biliary stents are well tolerated and can provide adequate symptom relief Citation[55].

Patients with advanced disease are, in general, older, frail and malnourished. In this setting, systemic agents have very little activity with no proven impact on survival, so the major goal is maximizing quality of life and providing palliative care. Gemcitabine, a nucleoside analogue, is well tolerated in the elderly. This agent reduces pain and improves performance status in approximately 30% of patients Citation[55]. Radiation therapy is also a possible intervention for palliation of symptoms when pain control is needed.

Hematological malignancies

Advanced age is one of the most important risk factors and adverse prognostic markers for hematological malignancies. The high prevalence of these conditions in the last decades of life, the increased tumor chemosensitivity and the potential curability of some hematological malignancies have encouraged the development of many research trials specifically designed for the elderly. Despite the development of new chemotherapeutic agents, therapeutic results in older adults are still far worse than in younger individuals Citation[56].

Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) is the most common and extensively studied hematological malignancy. The prevalence of NHL increases 100% for each 10-year cohort between 45 and 75 years, and then increases by nearly 400% among white males older than 75 years. Different studies have shown that older patients benefit from aggressive treatment and should be treated similarly to younger patients, with the intent to cure Citation[57]. Once complete remission has been achieved, the disease-free survival is not different between younger and older adults Citation[58].

Although a NHL increase has been noted for both genders, lymphoid cancers are more frequent in males than females throughout all age groups and across virtually all cancer registries in developed countries. Male predominance has been observed for most NHL subtypes, with male to female ratios >2 for high-grade and peripheral T-cell NHL, and >1 for most other subtypes. A similar occurrence has been noted for follicular lymphoma among whites. Only thyroid lymphoma is more common in women than men.

The increasing incidence of NHL in the elderly population is of note, as well as the under use of aggressive treatment among older patients. This is often the result of ageism and an assumption of poor tolerance to chemotherapy. Changes in chemotherapy response in older adults has been attributed to decrease in immune function and possibly higher susceptibility to infection, which in turn may render them more susceptible to many cancers including NHLs. Increased age has been identified as the main risk factor for CD56+ lymphomas with skin involvement, and for central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma; also, the association of systemic glucocorticoids use and an increased risk of NHL has been demonstrated.

The standard treatment for hematologic malignancies remains CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) or CHOP-like regimens, unless the patient presents with functional deficits, severe comorbidity or frailty with concomitant illnesses. The prophylactic use of bone marrow-stimulating factors has reduced the incidence, severity and duration of chemotherapy-induced leucopenia and anemia. The cost-effectiveness of these medications has been demonstrated Citation[58].

The incidence of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), along with its precursor, myelodysplasia, appears to be rising, particularly in the population older than 60 years. In adults, AML is by far the most common type of acute leukemia. The incidence of AML is slightly higher in males and in populations of European descent. Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL), a distinct subtype of AML, is more common among populations of Latino or Hispanic background.

Acute myeloid leukemia in the elderly is characterized by a high frequency of multilineage clonal involvement, immature phenotype of leukemic cells, presence of unfavorable cytogenic abnormalities and elevated functional activity of multidrug-resistant genes. Despite new drugs and hematopoietic growth factors, the optimal induction and post remission treatment for AML in the elderly remains highly controversial. In contrast to AML in younger adults, the prognosis for AML in the elderly remains poor. Complete remission rates rarely exceed 50%. The poor clinical outcomes appear primarily due to intrinsic differences in the biology of leukemia itself, as well as host factors and comorbid conditions linked to the aging process Citation[59],Citation[60].

Conclusions

Cancer is the most common cause of death in persons over 60 years of age, and the second most common cause of death in persons over 80 years of age. There is a sharp incident rise in cancer after the age of 64 for both men and women, but more so for men. With an estimated 25% of the population older than 65 years by mid-century, cancer will have an increasing impact on the healthcare of older men in the United States. Prostate, lung and colorectal cancers are the most common malignant tumors in old men around the world. Although genetic background plays an important role in cancer pathogenesis, geographical differences suggest that lifestyle is also an important element in the risk of developing these malignancies.

The comprehensive geriatric assessment can identify vulnerable patients who may still benefit from cancer treatment through modified chemotherapy regimens or substitution of less toxic agents. In frail patients, simple pharmacologic palliation of symptoms or low dose chemotherapy for tumor control may be the best options. Comprehensive geriatric assessment can also identify comorbidities that can be managed to make cancer treatment safer and more convenient. It is increasingly important in the elderly to watch for medical complications of cancer or its treatment, such as delirium, anemia, chronic pain, gait abnormalities and depression.

In older men, a careful approach using the comprehensive geriatric assessment to identify functional deficits, frailty and comorbidity is critical before embarking on cancer screening or a plan of cancer treatment. The approach to cancer in this group should always be viewed in the context of the state of health of the patient: strive for an early diagnosis when a survival benefit is likely, implement curative treatments when the patient is functional, use less toxic or palliative regimens when the patient is frail or has a high burden of comorbidity, and always focus on maintaining the best quality of life possible.

References

- Balducci L. New paradigms for treatment of elderly patients with cancer: The comprehensive geriatric assessment and guidelines for supportive care. J Support Oncol Nov/Dec, 2003; 1(4 Suppl 2)30–37

- Ershler W. Cancer: A disease of the elderly. J Support Oncol Nov/Dec, 2003; 1(Suppl 2)5–10

- Yancick R, Ries L A. Aging and cancer in America: Demographic and epidemiologic perspectives. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2000, 14: 17–23

- Suzman R M, Willis D P. The oldest old. Oxford University Press, New York, NY 1992

- Butler R N. Population aging and health. BMJ 1997; 315: 1082–1084

- Audisio R A, Repetta L, Zagonel V. Cancer in the elderly. UICC manual of clinical oncology, 8th edition, R E Pollock, J H Doroshow. Wiley-Liss, New Jersey 2004

- Yancick R, Ries L A. Cancer in older persons. Cancer 1994; 74: 1995–2003

- Smith D WE. Circulatory disease mortality in the elderly. Epidemiology 1997; 8: 501–504

- Hansen J. Common cancers in the elderly. Drugs and Aging 1998; 13(6)467–478

- Hajjar R R. Cancer in the elderly: is it preventable?. Clin Geriatr Med 2004; 20(3)553–564

- Mesut R, Waldert M. Protstate cancer in the aging male. Int J Men's Health & Gender 1; 1: 47–54

- Trimble E L, Christian M C. Cancer treatment and the older patient. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12(7 Pt 1)1956–1957

- Ershler W B. The influence of advanced age on cancer occurrence and growth. Cancer Treat Res 2005; 124: 75–87

- Ames B N, Shigenaga N K. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of Aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1993; 90: 7915–7922

- Balducci L, Yates J. General guidelines for management of older patients with cancer. Oncology 2000; 14: 221–227

- Lachs M S, Feinstein A R, Cooney L M, Jr, Drickamer M A, Marottoli R A, Pannill F C, Tinetti M E. A simple procedure for general screening for functional disability in elderly patients. Ann Int Med 1990; 112: 699–706

- Harvey H A. The management of hypercalcemia of malignancy. Support Care Cancer 1995; 3(2)123–129

- Salive M E, Cornoni-Huntley J, Guralnik J M, Phillips C L, Wallace R B, Ostfeld A M, Cohen H J. Anemia and hemoglobin levels in older persons relationship with age, gender and health status. J Am Geriatr Soc 1992; 40(5)489–496

- Chaves P H, Ashar B, Guralnik J M, Fried L P. Looking at the relationship beetween hemoglobin concentration and previous mobility difficulty in older women: should the criteria used to define anemia in older people be changed?. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002; 50: 1257–1264

- Morley J, Haddad R. Cancer as we age. Aging successfully 2002; 12(3)1–8

- Wingo P A, Ries L A, Rosenberg H M, Miller D S, Edwards B K. Cancer incidence and mortality, 1973–1995: a report card for the U.S. Cancer Mar 1998; 82(6)1197–1207

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in aging – United States and worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52(6)101–104, 106

- Smith C V, Bauer J J. Prostate cancer in men age 50 years or younger: A review of the department of defense Center for Prostate Disease Research Multicenter Cancer Database. J Urol 2000; 164: 1964–1967

- National Cancer Institute. Histologic grade and stage in Prostate Cancer Trends, 1973–1995, Accessed July 7, 2006. http://www.seer.cancer.gov//publications/prostate/grade.html

- Newcomer L M, Stanford J L, Blumenstein B A, Brawer M K. Temporal trends in rates of prostate cancer: Declining incidence of advanced stage disease 1974 to 1994. J Urol 1997; 158: 1127–1130

- Quin M, Babb P. Patterns and trends in prostate cancer incidence, survival prevalence, and mortality. BJU Int 2002; 90: 162–173

- Gronberg H. Prostate cancer epidemiology. Lancet 2003; 361: 859–864

- Lunfeld B. The ageing male: Demographics and challenges. World J Urol 2002; 20: 11–16

- Paquette E L, Sun L, Paquette L R, Connelly R, Mcleod D G, Moul J W. Improved prostate cancer-specific survival and other disease parameters: Impact of prostate-antigen testing. Urology 2002; 60: 756–759

- Ruchlin H S, Pellissier J M. An economic overview of prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2001; 92: 2796–2810

- Aus G, Abbou C C, Pacik D, Schmid H P, van Poppel H, Wolff J M, Zattoni F, EAU Working Group on Oncological Urology. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Eur Ural 2001; 40: 97–101

- Scherr D, Swindle P W, Scardino P T, National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Comprehensive cancer network guidelines for the management of prostate cancer. Urology 2003; 61(2 Suppl)14–24

- Fowler F J, Jr, Mcnaughton Collins M, Albensen P C. Comparison of recommendations by urologists and radiation oncologists for treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer. J Am Med Assoc 2000; 238: 3217–3222

- Havlik R J, Yancik R, Long S, Ries L, Edwards B. The National Cancer Institute on Aging and The National Cancer Institute SEER. Collaborative study on comorbidity and early diagnosis of cancer in the elderly. Cancer 1994; 74: 2101

- Balducci L, Beghe C. Cancer screening in the older person. Clin Geriatr Med 2002; 18: 505–528

- Mountain C F. Revisions in the international system for staging lung cancer. Chest 1997; 111(6)1710–1717

- Carney D N. Carboplatin/etoposide combination chemotherapy in the treatment of poor prognosis patients with small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 1995; 12(Suppl 3)S77–S83

- Janssen-Heijnen M L, Voebergh J W. Trends in incidence and prognosis of the histological sub-types of lung cancer in North America, Australia, New Zealand and Europe. Lung cancer 2001; 31: 123–137

- Fontana R S, Sanderson D R, Woolner L B, Taylor W F, Miller W E, Muhm J R. Lung cancer screening: The Mayo Program. J Occup Med 1986; 28: 746–750

- Melamed M R, Flehinger B J, Zaman M B, Heelan R T, Perchick W A, Martini N. Screening for early lung cancer. Results of the memorial Sloan-Kettering study in New York. Chest 1984; 86: 44–53

- Goodwin J S, Samet J M, Key C R. Stage at diagnosis of cancer varies with age of the patient. J Am Geriatr Soc 1986; 34: 20–26

- National Center for Health Statistics. NVSR Volume 51, Number 3. (PHS) 2003-1120. Feb 8, 2005. United States Life Tables, 2000. Accessed July 7, 2006. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/nvsr/51/51_03.htm

- Pagni S, McKelvey A, Riordan C, Federico J A, Ponn R B. Pulmonary resection for lung cancer in octogenarians. Ann Thorac Surg 1997; 63: 785–789

- Yamamoto K, Padilla Alarcon J, Calvo Medina V, Garcia-Zarza A, Pastor Guillen J, Blasco Armengod E, Paris Romeu F. Surgical results of stage I non-small cell lung cancer: Comparison between elderly and younger patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2003; 23: 21–25

- Gridelli C, Sheperd F. Chmetherapy for Elderly patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Chest 2005; 128(2)947–957

- Grobovsky L, Kaplon M, Karnard A B. Feature of cancer in frail elderly patients. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2000; 19: 2469

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance epidemiology and end results. Fast stats: Colon and rectum cancer, Accessed on July 6, 2006. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/faststats/sites.php?site = Colon + and + Rectum + Cancer&stat = Mortality

- National Cancer Institute. Surveillance epidemiology and end results. Cancer stat fact sheets. Cancer of the colon and rectum, Accessed on July 6, 2006. Available at: http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html

- Walsh J, Terdiman J. Colorectal cancer screening. JAMA 2003; 289: 1288–1296

- Arveux I, Boutron M C, El Mrini T, Arveux P, Liabeuf A, Pfitzenmeyer P, Faivre J. Colon cancer in the elderly: evidence for major improvements in health care and survival. Br J Cancer 1997; 76(7)963–967

- Honecker F, Kohne C H, Bokemeyer C. Colorectal cancer in the elderly: is palliative chemotherapy of value?. Drugs Aging 2003; 20(1)1–11

- Stein B N, Petrelli N J, Douglass H O, Driscoll D L, Arcangeli G, Meropol N J. Age and sex are independent predictors of 5-fluorouracil toxicity. Analysis of a large scale phase III trial. Cancer Jan 1995; 75(1)11–17

- Murr M M, Sarr M G, Oishi A J, van Heerden J A. Pancreatic cancer. CA Cancer J Clin Sep/Oct, 1994; 44(5)304–318

- Schmiegel W. Tumor markers in pancreatic cancer – current concepts. Hepatogastroenterology 1989; 36(6)446–449

- Bathe O F, Caldera H, Hamilton K L, et al. Diminished benefit from resection of cancer of the head of the pancreas in patients of advanced age. Journal of Surgical Oncology-Supplement 2001; 77: 115–122

- Boring C C, Squires T S, Tong T. Cancer statistics, 1994. CA Cancer J Clin 1994; 44: 7–26

- Zagonel V, Monfardini S, Tirelli U, Carbone A, Pinto A. Management of hematologic malignancies in the elderly: 15-year experience at the Aviano Cancer Center, Italy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol Sep 2001; 39(3)289–305

- Tirelli U, Zagonel V, Errante D, Fratino L, Monfardini S. Treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the elderly: an update. Hematol Oncol 1998; 16(1)1–13

- Balducci L, Lyman G H. Patients aged > or = 70 are at high risk for neutropenic infection and should receive hemopoietic growth factors when treated with moderately toxic chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19(5)1583–1585

- Pinto A, Zagonel V, Ferrara F. Acute myeloid leukemia in the elderly: biology and therapeutic strategies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2001; 39(3)275–287