Abstract

Objective. Cardiac surgery for patients >80 years has seen a dramatic increase in the last decade. The aim was to assess the long term survival and quality of life in this patient population.

Method. Patients who underwent cardiac surgery between 1995 and 2007 were identified and case notes reviewed. Follow-up was undertaken by personal interview with the patient or the nearest kin to complete a pre-planned questionnaire.

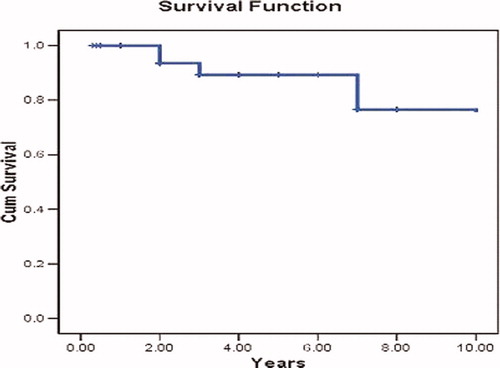

Results. Sixty six (M:F; 45:21) octogenarians had Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) only (55%), Aortic valve replacement (AVR) only (12%), Mitral valve replacement (MVR) only (3%), Valve and CABG (25%) and complex procedures (5%). Fifty-eight percent were elective procedures. Operative mortality was 8% (n = 5). Multivariate analysis identified complex procedures, prolonged bypass time and re-do/emergency surgery as predictors of death (p < 0.05). Median Intensive care unit (ICU) stay was 206 h (range 43–1176 h), with >70% leaving ICU in 72 h. Late mortality involved five patients (8%) who died at 10 yr; 7 yr; 3 yr; 1 yr; and 8 months; and 2 yr and 7 months, respectively. Survival by Kaplan–Meir was 8.8 yr (Standard Error (SE) = 0.66, Confidence interval (CI) 7.6–10.1), median survival was 10 yr and mean Barthel's index 17.7 (min 0, max 20).

Conclusions. Cardiac surgery can be accomplished in octogenarians with good long-term survival and quality of life. However, complex procedures, prolonged bypass and re-do/emergency surgery contribute significantly to mortality.

Introduction

Advances in medical care have resulted in a steadily aging population. As a result, more elderly patients are considered for cardiac surgery. Cardiac disease is more prevalent in the elderly and these patients are more likely to have medically refractory symptoms. There is a perception that cardiac surgery in the >80-year-old patients may carry a prohibitively high risk and there may be a reluctance to refer such patients with severe cardiac symptoms for this reason Citation[1],Citation[2]. The aim of this study was to investigate the long term survival and quality of life after cardiac surgery in patients >80 years old at the Royal Victoria Hospital between 1995 and 2007.

Methods and materials

Ethical approval was not needed since the study formed a part of good medical practice, however the study protocol and questionnaire was discussed with the Chairman of the hospital ethics committee before the commencement of the study. All patients aged 80 and above who underwent cardiac surgery between 1995 and 2007 were identified from theatre records and surgeon's log. Case notes were retrieved and reviewed. Data collected included pre-operative factors, operative factors, and outcomes. Pre-operative factors included age, sex distribution, elective vs. emergency cases and additive EuroScore were calculated for each patient where the required data was available. Operative factors included the type of operation, use of cardiopulmonary bypass, and the operating surgeon. Outcomes recorded included length of stay in the intensive therapy unit, overall postoperative hospital stay, morbidity and mortality.

Follow-up was undertaken by personal interview with the patient or the nearest kin or the nursing home care-attendant by telephone, a pre-planned questionnaire was then completed. This included questions about symptoms following surgery such as shortness of breath on exertion, orthopnoea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, exercise tolerance, and chest discomfort. Other questions included the time and cause of death where appropriate. A Barthel's Index of Activity of daily living score Citation[3] was calculated for each patient (Appendix 1). The closing interval was 4 weeks and cases in the last 4 months were excluded.

Data were recorded and analyzed on SPSS© version 12 statistical software. Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square test and the continuous variables by modified Mann–Whitney U test. Life expectancy and survival data were computed using the Kaplan–Meir method.

Results

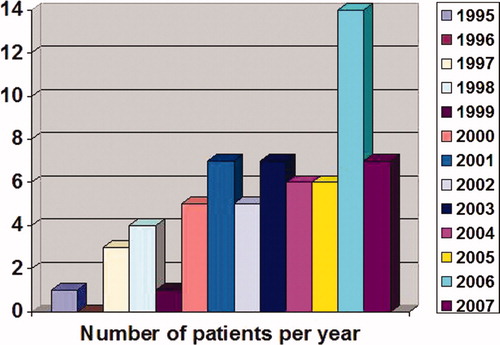

A total of 66 patients (68% male) were identified in the study period aged 80 to 88 with a mean age of 82.4 ± 1.28. The distribution of patients in each year is shown in . The Euroscore could be calculated in 58 patients; 12 (21%) had a Euroscore of ≥10; 46 patients (79%) had a Euroscore <10 including 11 patients with a Euroscore of 5. Thirty-six (55%) patients had coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) only; 8 (12%) had aortic valve replacement surgery (AVR) only; 2 (3%) patients had mitral valve replacement surgery (MVR) only; 17 (25%) patients had a combined valve and CABG procedure; there were 3 (5%) miscellaneous procedures including an AVR and mitral valve annuloplasty, AVR and aortic root enlargement and a Bentall procedure.

There were 38 (58%) elective cases and 28 (42%) non-elective cases. There were three redo operations which were all CABGs. The non-elective cases included three successful emergency operations one of which was a MVR and CABG for a post myocardial infarction mitral valve prolapse; and the other two CABG for unstable angina which were not suitable for coronary angioplasty due to the coronary artery disease anatomy. About 62 (94%) cases were performed with cardiopulmonary bypass; 4 (6%) were off-pump coronary artery bypass grafts; and 7 (11%) cases were performed by trainee surgeons under the supervision of the consultant surgeon (GC).

Operative mortality involved 5 (8%) patients including an in-patient AVR that died on the operating table (cause of death was not determined); an in-patient AVR + CABG that died of low output cardiac failure on Day 1 after surgery; a redo CABG x3 that died of graft failure on Day 1 after surgery; and two in-patient CABGs that died of post-operative myocardial infarctions. Multivariate analysis using logistic regression identified complex procedures (other than CABG or single valve procedures), prolonged bypass time (>100 min), and re-do/emergency surgery as predictors of mortality (p < 0.05).

Median stay in the cardiac surgery intensive care unit (CSICU) post-operatively was 206 h (8 days), range (43–1176 h). More than 70% of patients left CSICU in 72 h.

Late mortality involved five patients (8%) who died at 10 yr; 7 yr; 3 yr; 1 yr; and 8 months; and 2 yr and 7 months, respectively. Mean survival (Kaplan–Meir) was 8.8 yr, S.E:0.66 (CI 7.6–10.01), median 10 yr. This is illustrated in .

The quality of life at follow up revealed that three patients had a recurrence of angina and SOB; two patients were nursing home residents and one patient was still admitted for rehabilitation. The mean Barthel's index was 17.7 (min 0, max 20) where an index of >15 indicates good mobility and an index of 20 is excellent mobility Citation[3].

Discussion

The traditional markers for the success of a cardiac surgery department are survival rates, standard of procedures, freedom from re-operation, post-operative complications, length of hospital stay, improvement in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, and quality of life after surgery Citation[4]. Usually with the older patient, the perception is that they are more likely to score poorly in the above markers.

A typical referral such as ‘… I've got this delightful, otherwise fit, sprightly lady who's 80 but looks like 50 who needs her coronaries sorting out …’ would be approached with caution for according to Thibault ‘… there is nothing like cardiac surgery to bring out a patients true age …’Citation[5]. Cardiac surgeons appreciate that the tissues may be poor and so the procedure correspondingly more taxing. Procedural imperfections are cruelly punished and the chances of post-operative complications much higher Citation[6].

But as our study and other similar studies Citation[1],Citation[4],Citation[7-12] have shown cardiac surgery can be performed in the elderly with good long-term quality of life, and there is no reason to deny a patient cardiac surgery, where indicated, on the basis of age alone. Multivariate analysis identified complex procedures (other than CABG or single valve procedures), prolonged bypass time (>100 min) and re-do/emergency surgery as predictors of mortality but these procedures can be successfully performed in these patients if there is no other alternative and the risk to benefit ratio is of having the operation is satisfactory. The definition of long-term survival ranges from 18 months to greater than 5 years Citation[13].

Mean survival (Kaplan–Meir) of 8.8 yr, S.E:0.66 (CI 7.6–10.01) suggests that cardiac surgery can be performed and is well tolerated in this patient population. This means that these patients on average live into their 90 s hence good long-term survival which would be comparable to the national average. With a post-operative mean Barthel's Index of 17.7, these patients live on with a very good quality of life. The rehabilitation process is very important and geriatricians, general practitioners, practise nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, home care workers, and family support all play a major role.

The United Nations Populations division, in the 2004 revision of the World population prospects Citation[14] estimated that currently, 17% of over 60 s are 80 years or older. They predict that by 2050, 31% of over 60 s will be 80 years or older. This means, as has been the trend in recent years, patients presenting to cardiac surgery are getting older.

Coping mechanisms that have been suggested include careful pre-operative screening and optimisation Citation[11], doing more off-pump CABGs Citation[15] but cardiac surgery should not be postponed or denied an octogenarian on the basis of age alone as early surgical intervention for heart disease in this age group is justified Citation[9] before decompensation occurs.

Conclusion

This was a retrospective study on a relatively small sample of patients which highlights some interesting points regarding cardiac surgery in octogenarians. A multidisciplinary approach involving all specialists, including geriatricians, in the pre-operative and post-operative care of cardiac surgery patients ensures these patients get the best treatment indicated and available.

Patients are getting older, older patients will be getting cardiac surgery operations, the rehabilitation process is very important as patients may need time to recover from their operation. The period in rehabilitation is justified as the long term survival and quality of life can be very satisfactory.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the article.

References

- Logeais Y, Ingels A, Corbineau H, Langanay T, Leguerrier A. Cardiac surgery in the elderly. Bull Acad Natl Med 2006; 190: 855–871, discussion 871–876

- Engoren M, Arslanian-Engoren C, Steckel D, Neihardt J, Fenn-Buderer N. Cost, outcome, and functional status in octogenarians and septuagenarians after cardiac surgery. Chest 2002; 122: 1309–1315

- Collin C, Wade D T, Davies S, Horne V. The Barthel ADL index: a reliability study. Int Disabil Stud 1988; 10: 61–63

- Pritisanac A, Gulbins H, Rosendahl U, Ennker J. Outcome of heart surgery procedures in octogenarians: is age really not an issue. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther 2007; 5: 243–250

- Thibault G. Too old for what. N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 946–950

- UNSWORTH-WHITE J. Cardiac surgery for the elderly: a surgeon's perspective. Heart 1999; 82: 125

- Dalrymple-Hay M, Alzetani A, Aboel-Nazar S, Haw M, Livesey S, Monro J. Cardiac surgery in the elderly. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1999; 15: 61–66

- Fruitman D, MacDougall C, Ross D. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians: can elderly patients benefit? quality of life after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg 1999; 68: 2129–2135

- Huber C, Goeber V, Berdat P, Carrel T, Eckstein F. Benefits of cardiac surgery in octogenarians–a postoperative quality of life assessment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007; 31: 1099–1105

- Martínez-Sellés M, Hortal J, Barrio J, Ruiz M, Bueno H. Treatment and outcomes of severe cardiac disease with surgical indication in very old patients. Int J Cardiol 2007; 119: 15–20

- Srinivasan A K, Oo A Y, Grayson A D, Lowe R, Perry R A, Fabri B M, Rashid A. Mid-term survival after cardiac surgery in elderly patients: analysis of predictors for increased mortality. Interact CardioVasc Thorac Surg 2004; 3: 289–293

- Zaidi A, Fitzpatrick A, Keenan D, Nj O, Grotte G. Good outcomes from cardiac surgery in the over 70s. Heart 1999; 82: 134–137

- Stephens R J, Bailey A J, Machin D. Long-term survival in small cell lung cancer: the case for a standard definition. Medical Research Council Lung Cancer Working Party. Lung Cancer 1996; 15: 297–309

- United Nations. World population prospects: the 2004 revision, Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/ Accessed July, 2005

- Emaria R G, Carrier M, Fortier S, Martineau R, Fortier A, Cartier R, Pellerin M, Hébert Y, Bouchard D, Pagé, Perrault L P. Reduced mortality and strokes with off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting surgery in octogenarians. Circulation 2002; 106(12 Suppl 1)I5–I10