Abstract

BPH associated with LUTS and sexual dysfunction is common. We performed UroLift on 11 patients, average age 71 years (range 56–90). IPSS improved by an average of 9 points post-procedure. Pre-operatively their post-void residuals were 306.3 ml (range 120–499 ml SD [120.6]) and their QMAX was 7 ml/s (range 4–14 SD [2.8] ml/s). Post-procedure the post-void residual decreased by 35.4% at 4 months (mean difference – 106.3 ml). QMAX improved by an average of 1.7 ml/s, which was not statistically significant. No patients suffered any sexual dysfunction side effects and all patients were satisfied with their result. Hospital stay and theatre time were significantly reduced. Average length of stay was just 10.6 (6–18) hours and average theatre time just 18.7 (12–30) min. This is significantly faster than other surgery for LUTS. We therefore feel that there are significant benefits for both the patients, who are able to go home much faster, and also the hospital, who are able to perform far more surgeries for their patients. Patients also do not require an inpatient bed so patients should not be cancelled on the day of theatre.

Introduction

The incidence of male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) increases with age [Citation1]. The majority of LUTS are associated with benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH). BPH is one of the most commonly associated conditions of the aging male. Verhamme et al. found that there was a linear association of worsening LUTS and increasing age [Citation2].

BPH commonly presents with LUTS, but can also cause sexual dysfunction. This dysfunction can present as decreased libido, erectile dysfunction or decreased sexual satisfaction. These adversely impact a patient’s quality of life. Demir et al. found that patients with erectile dysfunction are also likely to have severe LUTS [Citation3]. In addition, the International Index of Erectile Function-5 questionnaire (IIEF-5) significantly correlates with both the IPSS (International Prostate Symptoms Score) and CLSS (Core Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Score) questionnaires (p = .0001) [Citation4].

BPH affects 3.2millions men in the UK and surgery for LUTS is one of the 10 most common surgeries performed by the NHS [Citation5]. With an aging population in the UK, the prevalence will rise further, bringing with it higher financial costs but also increased demand on healthcare resources.

Treatment is offered for BPH when symptoms are severe enough for the patients to seek intervention and there is evidence of bladder outflow obstruction. There are medical and surgical treatments. Medical treatment with alpha blockers and 5-alpha reductase inhibitors is very effective [Citation6] and data from the PLESS trial showed that finasteride a 5-alpha reductase inhibitor showed a reduction in the need for surgery as well as a reduction in the incidence of retention [Citation7,Citation8]. The MTOPS and the CombAT studies showed the benefit of using both agents in combination [Citation9,Citation10].

If medical therapy does not work because the patient still has significant symptoms, then they are offered surgical treatment. Currently, the gold standard surgical treatment is trans-urethral resection of the prostate (TURP). This has proven long-term effectiveness [Citation11]. TURP requires an inpatient stay and has the many side effects, the most sinister long-term effects include erectile dysfunction (2–10%), incontinence (2–10%) and retrograde ejaculation (65–75%) [Citation12]. These side effects can be concerning for the patient and can have a profound effect on the patient’s quality of life [Citation13]. Newer promising laser-based treatments including holmium or thulium laser enucleation of the prostate and photovaporisation are still associated with comparable complication rates with TURP [Citation14,Citation15].

Both these laser procedures and TURP require an inpatient stay between 24 and 48 h. They also require a general anaesthetic or a spinal anaesthetic. The procedures were taken from 30 to 90 min when anaesthetic time is combined with the surgical time. With current NHS pressures, these procedures are often cancelled with preference for patients requiring cancer treatments. This means that this group of patients are often suffering for considerable time before their treatment.

We report a new minimally invasive technique called UroLift. This works through permanent intra-prostatic implants which retract the enlarged prostate lobes, increasing the diameter of the prostatic urethra and alleviating LUTS [Citation16]. Clear advantages exist of UroLift compared to TURP. Firstly, it is minimally invasive involving no incisions or surgical resection and the technique can be performed under local anaesthesia as a hospital inpatient with an associated shorter operative time.

In this case series, we present a moderately sized cohort of 11 patients treated with UroLift and evaluate the efficacy and impact on quality of life at baseline and 4 months post-operatively. We also discuss its implications on the demand for healthcare resources and TURP waiting times. We hope this will help inform the medical community about how this new device can improve outcomes for men and improve the waiting times for bladder outflow surgery.

Patients and methods

Study design

A retrospective note analysis of 52 patients who were listed for TURP since April 7 2016 was performed. Of this 22%, 11 patients were suitable for the UroLift procedure.

Inclusion criteria

Age >50 years, IPSS of ≥10, QMAX of ≤14 ml/s, prostate volume and middle lobe assessed by flexible cystoscopy and digital rectal examination (DRE).

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from the trial if they were in retention with a catheter and had a large median lobe on flexible cystoscopy and if their prostatic volume was greater than 80 cc. Patients were also not excluded if they had a history of significant medical comorbidity and these cases were performed under local anaesthetic. Patients with suspected neurological conditions that could affect voiding were also excluded.

Statistical analysis

Baseline data and four month post-operative data were analysed using a two-sample equal-variance t-test. A value of p < .05 was defined as statistically significant ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics and procedural details for study participants.

UroLift equipment and surgical procedure

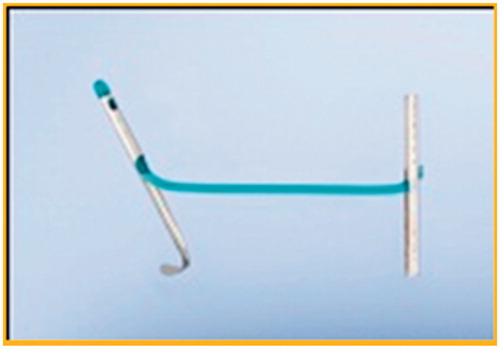

The implant is made of three parts (). The capsular tab is made of nitinol, the filament is monofilament polyester, and the urethral endpiece is stainless steel. Any endourology camera stack and light source can be used with the NeoTract components. The 2.9 mm zero degree telescope and 20Ch cystoscope was provided by NeoTract. This is slightly longer than the conventional 22Ch cystoscope and allows the UroLift implant device bridge to fit over the telescope and through the outer sheath.

A conventional cystoscopy is carried out to assess the bladder urothelium and proximity of ureteric orifices. The prostate is then assessed. As stated earlier, we selected cases with obstructed lateral lobes but not an obstructing median lobe. The UroLift device fits over the lens as a bridge and is a customised device made by NeoTract ().

On average, four implants per patient were used. Implants were inserted at 2 and 10 o’clock around 2 cm distal to the bladder neck; this opens the proximal prostatic urethra. Two further implants are inserted more distal at the level of the veru also at 2 and 10 o’clock to the initial implants opening the distal prostatic urethra. In larger prostates, further two implants can be inserted in the mid-prostatic urethra also at the 2 and 10 o’clock positions. Smaller prostates required 2 implants at 3 and 9 o’clock.

Once the position of the implant is found, lateral movement of the cystoscope compresses the prostate, the first trigger is then pulled to fire in the capsular tab, the device is then pushed forward to put tension on the monofilament suture till the white line appears in the scope, and then the second trigger is pulled to cut the suture and deliver the stainless steel urethral endpiece.

Results

The mean age of patients suitable for UroLift was 71 years (range 56–90). Pre-operative prostate volume was assessed by volume and upon gross visualisation via flexible cystoscopy. This demonstrated a mean volume of 45.5 CC (range 30–80CC) and cystoscopy identified all were occlusive, with 45% (n = 5) being small, 45% (n = 5) moderate and 10% (n = 1) large in size.

Baseline symptoms of BPH were measured using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) which showed a mean score of 25.6 (range 16–33). This value indicates the patients were severely symptomatic pre-operatively. In addition, average quality of life score was 5 (range 4–6).

Urinary function was quantified by measuring post-void bladder residual volumes and QMAX flow rates which were 306.3 ml (range 120–499 ml SD[120.6]) and 7 ml/s (range 4–14 SD[2.8] ml/s), respectively. Of our patient sample, 55% (n = 6) were on combination therapy of finasteride and tamsulosin prior to surgery. 45% were on monotherapy with 4 patients on tamsulosin and 1 on finasteride alone.

UroLift was performed under general anaesthesia in 73% of patients (n = 8), 18% (n = 2) under local anaesthesia and 1 patient under spinal. Mean total time in hospital was 10.6 h (range 6–18 h) with theatre time 18.7 min (range: 12–30 min) and operation time 8.5 min (range: 6–12 min). Our primary outcome analysis was measured at four months post-operatively in outpatient clinic. One Patient was unfortunately excluded from primary outcome analysis due to death from metastatic pancreatic cancer ().

Table 2. Primary outcomes from UroLiftTable Footnotea.

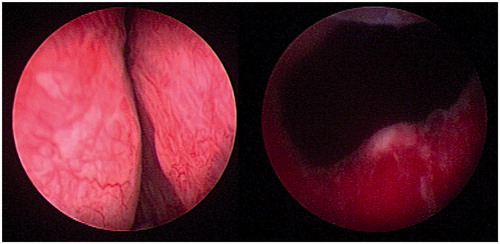

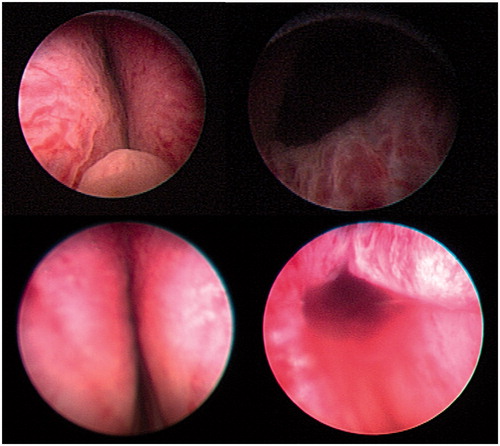

We report of a statistically significant reduction of 36% in the IPSS score at 4 months post-operatively (mean IPSS score difference – 9.1) (p = .02) This reduced from an average score of 25.4 at baseline to 16.3 at the 4-month follow-up appointment which corresponds from severely symptomatic to moderately symptomatic. and show the view of the prostatic urethra after the implants have been inserted. The prostatic urethra is more open and this corresponds with reduced IPSS.

Quality of life showed a statistically significant reduction of 1.6 points from 5.1 to 3.5 at 4-month follow-up (mean difference 3.5 (SD 2.2)) (p = .04). Post-void residual volume had a 35.4% decrease at 4 months (mean difference – 106.3 ml). This was also statistically significant to a 95% confidence interval (p = .04). QMAX was not statistically significant (p = .39) but showed an average increase in flow rate to 8.9 ml/s. This correlates with modest average increase of 1.7 ml/s on baseline data at 4 months post-operatively.

Discussion

This study shows UroLift is an effective method for the management of LUTS secondary to BPH. The average decrease of 9.1 in IPSS (SD = 8) is consistent with previous studies at similar end points [Citation17]. This is indicative that the procedure is an appropriate treatment for symptomatic BPH.

Furthermore, UroLift shows quantitative improvements in urinary flow rates and post-void residual volumes, which will have greater long-term benefits on urological health. Our group did not experience any sexual dysfunction which is beneficial to all of them. This is significant given the age of our cohort as older men have other risk factors for sexual dysfunction and so it is important that this procedure does not affect this. If they had a conventional TURP or other prostate surgery, there is a chance that at least some of the cohort would have had sexual dysfunction. The other benefit from our cohort was that men who would be very high risk for a general anaesthetic or spinal due to comorbidities were able to have this procedure under local anaesthetic. This gave them a significantly improved quality of life, and without this procedure, there were no other treatment options available to them. As well as an increase in patient satisfaction from symptomatic improvement, the UroLift procedure has significant implications on healthcare resources and financial costs.

There is a significantly reduced theatre time. The mean theatre time was 18.7 min, this ranged from 12 to –30 min. In this pilot study, the majority of cases were performed under general anaesthetic and that is why there is some variation in times as 2 were under local anaesthetic. The procedure time itself was much faster and had little variation. This procedure as we have showed can be performed under local anaesthetic and that could decrease theatre time further. This could even be performed in an endoscopy room and the theatre suite could therefore be free for other surgeons and patients. Given the growing waiting lists that we have in urology, this could greatly improve the service for these patients as well as the patients, having their surgery faster due to the newly available theatre time. TURP takes much longer in theatre and several patients could be treated by UroLift in the time taken for one TURP. Financially, there is an incentive for the hospital, as with the TURP tariff if the patient stays in hospital for 3 days, there is a potential loss to the hospital of £994 per procedure. UroLift has a similar tariff but the patient can go home on the same day and so there is a much greater profit margin.

As the patient does not need an inpatient bed, there is very little chance of cancellation. They will require an ambulatory care bed; however, this is not dependent on emergency admissions and so it is much more predictable, easier to manage for the bed managers and so there should not be the concern for the patient about a cancellation on the day of surgery. As this has the potential to be done in endoscopy, there is also not the concern that a case in the morning of the theatre list runs over time and there is no theatre time left to carry out their procedure.

Patients not fit for conventional TURP could also have this procedure carried out as it is reasonably non-invasive compared to TURP. With an aging population, there may well be a lot of men in the future who have significant LUTS but are not fit for spinal or general anaesthetic. These prostatic implants could be put in under local anaesthetic and could dramatically improve their quality of life where as previously nothing could be done for their symptoms other than a long-term catheter and its associated complications.

Post-operative recovery is much faster, as the risk of a blocked catheter, blood transfusions, TUR syndrome and infections that occur with TURP are much lower. The later risk of erectile dysfunction is also lower. With our aging population, men are sexually active for longer and so this is a very real concern for a lot of men undergoing surgery for BPH [Citation18].

We have shown UroLift to be a very successful treatment option for BPH and with the current climate in the NHS this is something that we are going to use in our department to provide a faster and more effective service to our men requiring surgery for the LUTS. We need to recruit more patients to fully validate this treatment as well as follow our patients up for longer to ensure that this treatment does not just provide a temporary improvement in LUTS.

Disclosure statement

No financial benefits have been received as a result of this study.

References

- Logie J, Clifford GM, Farmer RD. Incidence, prevalence and management of lower urinary tract symptoms in men in the UK. BJU Int. 2005;95:557–562.

- Verhamme KMC, Dieleman JP, Bleumink G, et al. Incidence and prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic hyperplasia in primary care—the Triumph project. Eur Urol. 2002;42:323–328.

- Demir O, Akgul K, Akar Z, et al. Association between severity of lower urinary tract symptoms, erectile dysfunction and metabolic syndrome. Aging Male. 2009;12:29–34.

- Nakamura M, Fujimura T, Nagata M, et al. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and sexual dysfunction assessed using the core lower urinary tract symptom score and International Index of Erectile Function-5 questionnaires. Aging Male. 2012;15:111–114.

- Kirby RS, Kirby M, Fitzpatrick JM. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: counting the cost of its management. BJU Int. 2010;105:901–902.

- Yassin A, Saad F, Hoesl CE, et al. Alpha-adrenoceptors are a common denominator in the pathophysiology of erectile function and BPH/LUTS-implications for clinical practice. Andrologia. 2006;38:1–12.

- Roehrborn CG, McConnell JD, Lieber M, et al. Serum prostate-specific antigen concentration is a powerful predictor of acute urinary retention and need for surgery in men with clinical benign prostatic hyperplasia. PLESS Study Group. Urology. 1999;53:473–480.

- Favilla V, Russo GI, Privitera S, et al. Impact of combination therapy 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5-ARI) plus alpha-blockers (AB) on erectile dysfunction and decrease of libido in patients with LUTS/BPH: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Aging Male. 2016;19:175–181.

- McConnell JD, Roehrborn CG, Bautista OM, et al. The long-term effect of doxazosin, finasteride, and combination therapy on the clinical progression of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2387–2398.

- Roehrborn CG, Siami P, Barkin J, et al. The effects of dutasteride, tamsulosin and combination therapy on lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic enlargement: 2-year results from the CombAT study. J Urol. 2008;179:616–621.

- Mishriki SF, Grimsley SJ, Nabi G, et al. Improved quality of life and enhanced satisfaction after TURP: prospective 12-year follow-up study. Urology. 2008;72:322–326.

- British Association of Urological Surgeons (BAUS). Transurethral Prostatectomy (TURP) for benign disease – information about your procedure from BAUS [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2017 Apr 17]. Available from: http://www.baus.org.uk/_userfiles/pages/files/Patients/Leaflets/TURP%20for%20benign.pdf

- Rassweiler J, Teber D, Kuntz R, et al. Complications of transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)-incidence, management, and prevention. Eur Urol. 2006;50:969–980.

- Montorsi F, Naspro R, Salonia A, et al. Holmium laser enucleation versus transurethral resection of the prostate: results from a 2-center, prospective, randomized trial in patients with obstructive benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2004;172:1926–1929.

- Cornu JN, Ahyai S, Bachmann A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of functional outcomes and complications following transurethral procedures for lower urinary tract symptoms resulting from benign prostatic obstruction: an update. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1066–1096.

- Jones P, Rajkumar GN, Rai BP, et al. Medium-term outcomes of Urolift (minimum 12 months follow-up): evidence from a systematic review. Urology. 2016;97:20–24.

- Woo H, Chin PT, McNicholas TA, et al. Safety and feasibility of the prostatic urethral lift: a novel, minimally invasive treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). BJU Int. 2006;108:82–88.

- Marandola P, Musitelli S, Noseda R, et al. Love and sexuality in aging. Aging Male. 2002;5:103–113.