Abstract

Treating male lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) by targeting the prostate would have limited effect on overactive bladder (OAB) symptoms. This study assessed perceived symptoms and quality of life (QoL) of male patients with OAB treated with an α-blocker plus solifenacin in daily clinical practice. Male patients aged ≥40 years were included after the decision was made to initiate treatment with an α-blocker for LUTS plus solifenacin for OAB symptoms. The primary endpoint was change in patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC) questionnaire score over 6 months. Other assessments included the OAB-questionnaire short form (OAB-q SF) and International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS). Interpretation of the study data was hindered by not meeting the enrollment target and a high dropout rate. In 36 evaluable patients, mean (SD) PPBC score improved from 4.3 (0.93) at baseline (“moderate” to “severe” problems) to 3.5 (1.06) at month 6 (“minor” to “moderate” problems). OAB-q SF scores and total IPSS also improved. In this patient population, treatment with solifenacin and an α-blocker resulted in improvements in male patient perception of their LUTS and QoL, although the results should be interpreted with caution due to the low number of patients with complete data.

Introduction

While female lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) are usually recognized as overactive bladder (OAB), male LUTS are often attributed to bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) [Citation1–3]. Indeed, the severity of male LUTS has been shown to often correlate with greater prostate volume [Citation4]. As such, LUTS in men are often initially treated with drugs that target the prostate, such as α-blockers (to reduce smooth muscle tone in the prostate and bladder) or 5-α reductase inhibitors (to reduce prostate volume). However, it is now recognized that not all male LUTS are directly prostate-related; patients may have LUTS without BOO, and patients with BOO may also have OAB [Citation1–3,Citation5,Citation6]. For example, in a study of 160 men with LUTS, 68% had BOO, of whom 46% had concomitant detrusor instability [Citation5]. In a further study of 162 men with LUTS, 45% of those with BOO also had OAB [Citation6]. Consequently, treatment with α-blocker or 5-α reductase inhibitors may have a positive impact on the voiding symptoms associated with BPH and BOO (slow, split or intermittent stream, hesitancy, straining and terminal dribble) but limited effect on the storage symptoms associated with OAB (urgency, frequency, nocturia and urinary incontinence) [Citation1–3]. Effective treatment may be further complicated by patient factors, including advancing age and bladder wall thickness [Citation7,Citation8].

In an epidemiological study conducted in the USA, United Kingdom and Sweden, approximately half of men and women experienced at least one lower urinary tract symptom at least “often”, with symptom rates highest in the USA, followed by the United Kingdom and Sweden [Citation9]. Prevalence estimates based on a 2001 survey suggest that over 1.8 million of the approximately 10 million people in Sweden (2016) may experience OAB symptoms of some degree (although not necessarily requiring treatment) [Citation10,Citation11]. Following lifestyle adjustments, bladder and/or pelvic floor training, antimuscarinics were first-line pharmacological treatment for OAB in Sweden at the time of this study [Citation12]. In December 2012, the first β3-adrenergic agonist, mirabegron, was approved for use in OAB in Sweden, but it was not available at the time of this study [Citation13]. Historically, antimuscarinics have been used primarily in women because of theoretical concerns that the inhibitory action on detrusor contraction power may increase the risk of urinary retention in men with concomitant BOO [Citation14]. However, increased risk was not observed during studies of tolterodine treatment in men with LUTS [Citation15–18] and few instances of urinary retention were observed during studies of other antimuscarinic agents [Citation14]. The treatment of male LUTS is required to address the overlapping obstructive voiding and storage symptoms in many patients. Consequently, there is a growing body of evidence demonstrating that combining antimuscarinics with an α-blocker may further improve LUTS for some men [Citation2,Citation19–22]. At the time of study initiation, there were no Swedish or international guidelines proactively recommending α-blocker and antimuscarinic combination therapy for male patients with LUTS. However, the 2016 European Association of Urology guidelines for treatment of non-neurogenic male LUTS recommends combination treatment with an antimuscarinic agent and an α-blocker in patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS if relief of storage symptoms is insufficient with monotherapy with either drug [Citation23].

LUTS have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life (QoL), with psychological and practical implications often necessitating complex coping strategies [Citation24,Citation25]. In particular, the storage symptoms associated with OAB are perceived as highly bothersome and significantly more so than voiding symptoms [Citation26,Citation27]. As such, patient-reported outcomes are highly important measures of treatment success for both OAB and LUTS [Citation28].

The purpose of this noninterventional study was to collect information on the perceived symptoms and QoL from male patients suffering from OAB symptoms treated with solifenacin in combination with an α-blocker in daily clinical practice. In addition, we investigated whether any perceived change in LUTS and QoL persisted beyond 12 weeks of treatment.

Methods

Patients

This was a 6-month, noninterventional study conducted between 2012 and 2014 among male patients aged ≥40 years attending a study clinic, mainly specialist urology clinics/departments or urology specialist private practices. Patients with OAB symptoms were included after the decision had been made to initiate treatment with solifenacin 5 or 10 mg daily in combination with an α-blocker for LUTS. Patients were to have a diagnosis of OAB (≥8 micturitions and ≥3 urgency episodes per 24 h). Patients who had been under treatment with an α-blocker for at least 6 weeks prior to the study and those who were to start α-blocker treatment simultaneously with solifenacin were eligible. Major exclusion criteria included history of acute urinary retention, symptomatic acute urinary tract infection, previous urethral, prostate or bladder neck surgery, diagnosis of prostate or bladder cancer, prostate-specific antigen (PSA) > 10 ng/mL, urethral stricture, onabotulinumtoxinA treatment within last 6 months and residual urine volume ≥150 mL.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Good Clinical Practice. In addition, all applicable local laws and regulatory requirements in Sweden were adhered to. All patients provided written informed consent.

Assessments

The primary objective of the study was to determine if solifenacin in combination with an α-blocker improved patients’ subjective perception of urinary problems, as measured by the patient perception of bladder condition (PPBC) questionnaire. Secondary objectives were to investigate the treatment effect on OAB symptom bother and QoL (measured by OAB-questionnaire short form [OAB-q SF]), urgency and urge incontinence episodes (assessed by a 24-h voiding diary), urinary symptoms (assessed by the International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS]) and to determine the use of incontinence pads. All assessments were conducted at a baseline visit at the study center (baseline) and three follow-up assessments 2, 4 and 6 months postbaseline, when questionnaires were completed by the patients at home and returned by post. There were no additional visits, medical examinations, or laboratory tests.

Responses to the single PPBC question “Which of the following statements describes your bladder condition best at the moment?” were scored from 1 (“My bladder does not cause me any problems at all”) to 6 (“My bladder condition causes me many severe problems”), such that a higher score indicated more severe condition.

The six OAB-q SF questionnaire questions related to OAB symptom bother (OAB-6) were scored from 1 (“not at all”) to 6 (“a very great deal”), such that the lowest score was 6 and the highest was 36, giving a score range of 30. The symptom severity score was calculated by creating a sum of the raw score from the six questions and transforming the value according to the formula below, such that higher OAB-6 scores indicate greater symptom severity or bother. The 13 OAB-q SF questionnaire questions related to QoL (OAB-13) were scored from 1 (“none of the time”) to 6 (“all of the time”), such that the lowest score was 13 and the highest was 78, giving a score range of 65. The QoL score was calculated by creating a sum of the raw score from the 13 questions and transforming the value according to the formula below, such that higher OAB-13 scores indicate better QoL.

A 24-h voiding diary was completed at each assessment, collecting information on time of voiding, urgency and urge incontinence for up to 15 episodes per 24 h. The number of urgency episodes and urge incontinence episodes per 24 h was categorized into “normal” (0–8 episodes), “above normal” (9–<15 episodes) and “extreme” (≥15 episodes). Episodes of urgency were scored as mild, moderate or severe, and episodes of urge incontinence assessed as no leakage, drops/damp, wet-soaked or bladder emptied.

Questions 1–6 of the IPSS, concerning frequency of urinary symptoms (incomplete emptying, frequency, intermittency, urgency, weak stream and straining), were scored from 0 (“not at all”) to 5 (“almost always”). Question 7, concerning frequency of nocturia, was scored from 0 (“none”) to 5 (“5 times or more”). Total IPSS score (urinary symptom questions 1–7) was categorized into “mildly symptomatic” (total score 0–7), “moderately symptomatic” (total score 8–19) and “severely symptomatic” (total score 20–35). The eighth QoL question “If you were to spend the rest of your life with your urinary condition the way it is now, how would you feel about that?” was scored from 0 (“delighted”) to 6 (“terrible”).

Patients answered whether they used pads, and if so, how many per week.

Study patients were to report ending of study medication and reason by sending in the questionnaires at months 2, 4 and 6. If a patient reported adverse events (AEs), they were followed up according to the protocol. AEs that were deemed “possibly” or “probably” related to study drug (e.g. AEs whose relationship to the study drugs could not be ruled out) were reported as adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

Statistical analyses

A sample size of 150 would have 90% power to detect a sufficient change on the PPBC scale from baseline to months 2, 4 and 6. However, due to the low number of patients enrolled the data are only reported descriptively.

Two treatment groups were prospectively defined: patients who were receiving treatment with an α-blocker for at least 6 weeks prior to the study (the “α-blocker treatment-experienced” group) and those who were to start α-blocker treatment simultaneously with solifenacin (termed “α-blocker treatment-naïve” group).

The full analysis set (FAS) was the main analysis set for primary and secondary endpoints and included all enrolled patients who signed the informed consent form and who provided data at baseline and at the two-month follow-up assessment. The safety analysis set (SAS) was used for demographic/baseline characteristics and AEs and included all patients who received at least one dose of solifenacin. The per protocol set (PPS) was considered secondary to the FAS for primary and secondary endpoints and included all patients who had no major protocol violations and completed the full six-month study period.

Statistical analyses were performed, although as enrollment did not reach the planned number of patients (approximately 50% of patients were enrolled), the data are only reported descriptively for the FAS population. Continuous variables were summarized with descriptive statistics and two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for mean changes from baseline, wherever relevant. For categorical variables, the number and percentage of subjects by each category were summarized. All data were analyzed by time point (baseline, 2 months, 4 months and 6 months) as well as by the two treatment groups (α-blocker treatment-experienced and α-blocker treatment-naïve). All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 or higher (Cary, NC).

Results

Patients and treatment

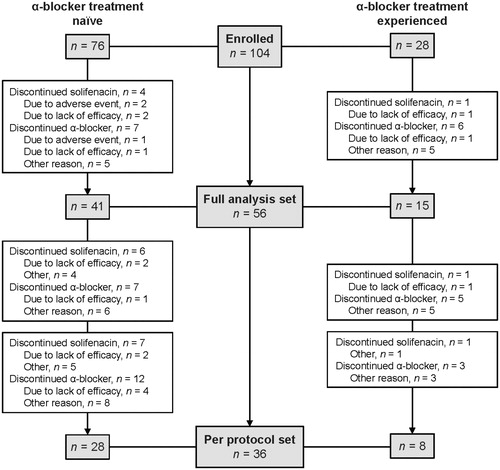

A total of 104 patients enrolled from 13 centers in Sweden (SAS; ). Of these patients, 56 provided data at the two-month follow-up and were included in the FAS. Only 36 patients (35% of those enrolled) provided data for all four PPBC questionnaires and completed the study (PPS).

Figure 1. Patient disposition. NOTES: Three patients provided informed consent but did not have baseline data; hence, 104 patients were enrolled, but 101 comprised the safety analysis set. Reasons for discontinuation were not systematically collected, and the reasons are therefore unknown in some cases. Patients may have discontinued for more than one reason.

The mean (SD) patient age was 65.1 (9.4) years (). Overall, half of the patients received a 5 mg daily dose of solifenacin (). In the α-blocker treatment-experienced group, 16 (61.5%) patients received a 5 mg daily dose of solifenacin, whereas in the α-blocker treatment-naïve group, 33 (44.0%) patients received a 5 mg daily dose of solifenacin.

Table 1. Summary of demographics and baseline characteristics (safety analysis set).

At month 2, 4 and 6 follow-ups, five (5%), seven (7%) and eight patients (8%) in the overall FAS, respectively, reported that they had discontinued solifenacin treatment, with more patients in the α-blocker treatment-naïve group discontinuing compared with the α-blocker treatment-experienced group (). The reason for discontinuation reported at the month 2, 4 and 6 follow-ups was “lack of efficacy”, in three (3%), three (3%) and two (2%) patients, respectively. Two patients (2%) reported discontinuing solifenacin due to AEs at the month 2 follow-up. The remaining patients discontinued for “other” reasons, which were not recorded. At month 2, 4 and 6 follow-ups, 13 (13%), 12 (12%) and 15 patients (15%), respectively, reported that they had discontinued α-blocker treatment, with 10 (10%), 11 (11%) and 11 (11%), respectively, doing so for “other” reasons, which were not recorded.

Table 2. Patients using solifenacin and α-blocker at 2, 4 and 6 months (safety analysis set).

Effectiveness

PPBC

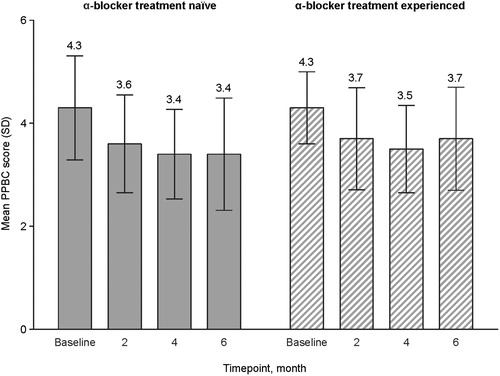

In the overall FAS, the mean (SD) PPBC score improved 0.8 points, from 4.3 (0.93) at baseline, corresponding to between “moderate problems” and “severe problems” to 3.5 (1.06) at month 6, corresponding to between “minor problems” and “moderate problems” (). Score improvements in the α-blocker treatment-naïve and α-blocker treatment-experienced groups were comparable ().

OAB-q SF

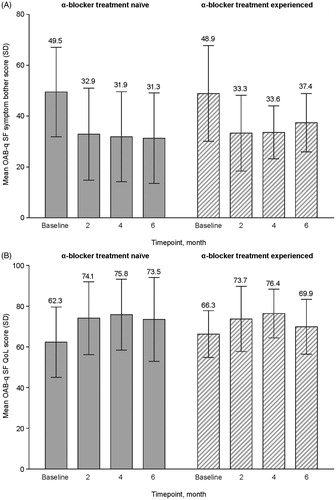

Transformed OAB-q SF symptom bother and QoL scores are depicted in . In the overall FAS, the mean (SD) OAB-6 score was reduced by 16.6 points, from 49.3 (17.8) at baseline to 32.7 (16.6) at month 6, indicating that symptoms were less bothersome after 6 months of treatment. Mean (SD) OAB-13 score was increased by 9.4 points, from 63.3 (15.9) at baseline to 72.7 (19.1) at month 6, indicating an improvement in QoL after 6 months of treatment. Score improvements in the α-blocker treatment-naïve and α-blocker treatment-experienced groups were comparable (). The results should be interpreted with caution due to the lower number of respondents at end of study (39, compared with 56 at baseline).

Voiding diary

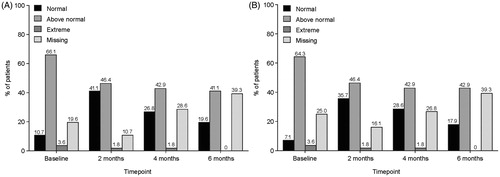

According to 24-h voiding diaries completed at baseline and months 2, 4 and 6, there was no obvious change in urgency and urge incontinence during the study (). Most patients reported “mild” urgency. The majority of patients had a number of urgency episodes that was “above normal” (9–14 episodes in a 24-h period), followed by “normal” (0–8 episodes in a 24-h period; ). With regards to urge incontinence, most patients reported “no leakage” for most visits and micturition episodes (>70% of subjects). The majority of patients had a number of leakages that was “above normal” (9–14 episodes in a 24-h period) followed by “normal” (0–8 episodes in a 24-h period; ). However, at month 6, almost 40% of patients had missing data, thus these data should be interpreted with caution.

IPSS

Overall, for questions 1–6 of the IPSS (urinary symptoms), there was a shift during the study from the majority of patients answering “almost always” or “about half the time” at baseline to the majority of patients answering “not at all” or “less than 1 time in 5” at month 6. This shift was observed for all six questions (incomplete emptying, frequency, urgency, weak stream, intermittency and straining). Similarly, responses to question 7 regarding the number of nocturia episodes shifted from the majority of patients responding “twice” at baseline (41.8%) to “once” at 6 months (35.9%).

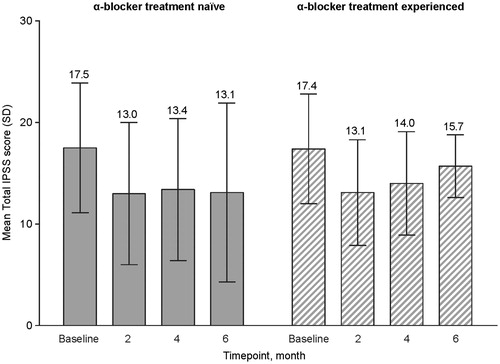

In the overall FAS, a small improvement in total IPSS was observed from baseline to end of study (). At baseline, mean (SD) total IPSS was 17.4 (6.1), corresponding to the upper end of the “moderately symptomatic” category. At month 6, the total IPSS in the FAS was 13.7 (7.9), also corresponding to “moderately symptomatic” but suggesting a small decrease in symptom severity. Total IPSS at each time point from baseline to month 6 was comparable between the α-blocker treatment-naïve group and the α-blocker treatment-experienced group ().

For question 8 of the IPSS (QoL), mean (SD) score was 4.0 (1.0) at baseline, corresponding to an average score of “mostly dissatisfied”, and 2.7 (1.6) at month 6, corresponding to an average score between “mostly satisfied” and “mixed – about equally satisfied and dissatisfied”.

Use of incontinence pads

Use of incontinence pads was very limited, with 7/56 (12.5%), 6/54 (11.1%), 3/44 (6.8%) and 5/37 (13.5%) patients using them at baseline and months 2, 4 and 6, respectively.

Safety

ADRs were reported in six of 104 patients in the SAS. Four of the six patients reported urinary retention, urgent need to urinate, dry mouth, dizziness, red and swollen eye lid and rash. Two patients reported “side effects”, with no further specification of this term. No deaths or serious AEs were reported.

Discussion

The results of this noninterventional study indicate an improvement in male patients’ perception of their LUTS and QoL under combination treatment with solifenacin and an α-blocker in daily clinical practice. With regards to the primary objective of change in PPBC questionnaire score, an improvement was indicated from baseline to 6 months, with a shift in mean score from between “moderate” and “severe” problems to between “minor” and “moderate” problems, respectively. Both OAB symptom bother (as measured by the OAB-6 questionnaire) and QoL (as measured by the OAB-13 questionnaire) also improved over the 6-month study period, in addition to a small improvement in total IPSS. It is unclear if there is any difference between initiating solifenacin and α-blocker treatment simultaneously or initiating α-blocker treatment ≥6 weeks prior to solifenacin, as statistical comparisons could not be performed due to the limited number of patients enrolled. The results demonstrate that the patient-perceived changes in LUTS, including OAB symptoms specifically, and QoL persisted for up to 6 months after starting treatment. Six patients reported an ADR, with no new safety issues noted.

These results contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting combination therapy with an α-blocker and solifenacin for male patients with LUTS with storage symptoms and when monotherapy is inadequate. After initiation of this noninterventional study, a 12-week randomized controlled trial demonstrated that combination therapy with solifenacin and the α-blocker tamsulosin offered significant improvements in micturition frequency and voided volume compared with tamsulosin monotherapy in men with voiding and storage symptoms [Citation29]. Although improvements in total IPSS were not statistically significantly better for solifenacin and tamsulosin combination therapy over tamsulosin monotherapy in the overall study population, improvements in QoL measures were noted in men with both voiding and storage symptoms at baseline. Accordingly, improvements in patients’ perception of their symptoms have also been observed in two relatively small studies of solifenacin as add-on therapy to tamsulosin in BPH patients with OAB symptoms [Citation30] and those with LUTS suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction [Citation31]. In a long-term study of a single solifenacin and tamsulosin oral-controlled absorption system tablet, the improvements in IPSS and urgency and frequency symptoms seen during the initial 12-week study [Citation32] were maintained for up to 52 weeks [Citation33]. Since the conduct of this study, the European Association of Urology guidelines for treatment of non-neurogenic male LUTS have been updated to recommend combination treatment with an antimuscarinic agent and an α-blocker in patients with moderate-to-severe LUTS if relief of storage symptoms is insufficient with monotherapy with either drug [Citation23].

The men in this study population were generally older (mean age 65 years) than the male and female patient population with OAB in the phase 3 trials of solifenacin (mean age 55–58 years) [Citation34–36], which suggests that solifenacin may be prescribed to older men in clinical practice. This has been observed in other real-life studies [Citation37–39] and may reflect exclusion of elderly patients with multiple comorbidities from clinical trials.

The study was conducted in a real-life setting, with analyses based on assessment methods and parameters used in daily clinical practice. As such, there were no additional healthcare visits, medical examinations or laboratory tests. With respect to the generalizability of the study results, this can be considered a strength of the study. However, not all data were collected for all patients, and at month 6, approximately, 50% of the data were missing. Reasons for discontinuation were not systematically collected, with a significant number of patients discontinuing for “other” reasons that are unknown. It is likely that many patients simply forgot to return their questionnaires by post at 2, 4 and 6 months. In retrospect, contact with a study physician/nurse, reminders to return questionnaires, and a final follow-up visit at a study center might have increased the number of completed questionnaires. Furthermore, only approximately 50% of the 200 patient enrollment target was met due to recruitment difficulties. A contributing factor may be that the majority of the study centers were specialist urology clinics/departments and urology specialist private practices, whereas the target patients for this study were more likely to be treated by their primary care physicians. The drop-out rate was also more than double what was expected (65% vs. 25%). Due to the limited number of patients enrolled, statistical tests were not performed and the data were reported solely descriptively. Consequently, the sample might be severely biased and the results should be interpreted with caution.

Specifically with regards to the PPBC score, the change from baseline was approximately 1, lower than the anticipated score of 1.5 that the study was powered to detect if 150 patients completed the study. In addition, the anticipated change in PPBC was estimated from mainly OAB studies including both male and female patients, whereas the patients in this study were all male.

The severity of OAB problems may not have been sufficient to result in improvement with solifenacin and α-blocker treatment in this study, since “mild urgency” was most frequently reported for urgency and “no leakage” was most frequently reported for urge incontinence. For example, in previous studies, response to therapy with tolterodine or oxybutynin was greater in patients with moderate-to-severe OAB [Citation40–42]. Furthermore, it is not known how many of the enrolled patients had a primary diagnosis of OAB. Patients were receiving an α-blocker, indicating an obstructive component to their LUTS suggestive of involvement of other pathologies contributing to their bladder symptoms. However, the combination treatment with solifenacin and an α-blocker in this study did result in an improvement in patients’ impression of their LUTS. As this study was 6 months in duration, it is not known whether the improvements noted during this period would be maintained over a longer period of treatment.

In summary, treatment with solifenacin and an α-blocker resulted in improvements in male patient perception of their LUTS and QoL, although interpretation of the study data is significantly hindered by not meeting the enrollment target.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients who took part in the study and the following study investigators: Christer Dahlstrand (Göteborg), Christian Linberg (Lund), Lars Sandfeldt (Stockholm), Håkan Wallberg (Skärholmen).

Disclosure statement

Lars Henningsohn has served on advisory boards and as a lecturer for Astellas Pharma AB. Suzanne Kilany and Maja Svensson are employees of Astellas Pharma A/S. Judith Jacobsen has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albisinni S, Biaou I, Marcelis Q, et al. New medical treatments for lower urinary tract symptoms due to benign prostatic hyperplasia and future perspectives. BMC Urol. 2016;16:58.

- Moss MC, Rezan T, Karaman UR, et al. Treatment of concomitant OAB and BPH. Curr Urol Rep. 2017;18:1.

- Chapple CR, Roehrborn CG. A shifted paradigm for the further understanding, evaluation, and treatment of lower urinary tract symptoms in men: focus on the bladder. Eur Urol. 2006;49:651–658.

- Yeh HC, Liu CC, Lee YC, et al. Associations of the lower urinary tract symptoms with the lifestyle, prostate volume, and metabolic syndrome in the elderly males. Aging Male. 2012;15:166–172.

- Hyman MJ, Groutz A, Blaivas JG. Detrusor instability in men: correlation of lower urinary tract symptoms with urodynamic findings. J Urol. 2001;166:550–552.

- Knutson T, Edlund C, Fall M, et al. BPH with coexisting overactive bladder dysfunction–an everyday urological dilemma. Neurourol Urodyn. 2001;20:237–247.

- Salah Azab S, Elsheikh MG. The impact of the bladder wall thickness on the outcome of the medical treatment using alpha-blocker of BPH patients with LUTS. Aging Male. 2015;18:89–92.

- Singam P, Hong GE, Ho C, et al. Nocturia in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: evaluating the significance of ageing, co-morbid illnesses, lifestyle and medical therapy in treatment outcome in real life practice. Aging Male. 2015;18:112–117.

- Coyne KS, Sexton CC, Thompson CL, et al. The prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) in the USA, the UK and Sweden: results from the epidemiology of LUTS (EpiLUTS) study. BJU Int. 2009;104:352–360.

- Milsom I, Abrams P, Cardozo L, et al. How widespread are the symptoms of an overactive bladder and how are they managed? A population-based prevalence study. BJU Int. 2001;87:760–766.

- Statistiska Centralbyrån. Statistical database - population by age and sex 2016. [cited 2017 Feb 21]. Available from: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se.

- Swedish Medical Products Agency. Behandling av urinträngningar och trängningsinkontinens - överaktiv blåsa - ny rekommendation. Läkemedelsverket. 2011;22:12–21. Available from: https://lakemedelsverket.se/upload/halso-och-sjukvard/behandlingsrekommendationer/Ny%20rekommendation%20%E2%80%93%20%20behandling%20av%20urintr%C3%A4ngningar%20och%20tr%C3%A4ngningsinkontinens%20%E2%80%93%20%C3%B6veraktiv%20bl%C3%A5sa%20%5B1%5D.pdf [last accessed Feb 21, 2017].

- Swedish Medical Products Agency. Läkemedelsverket informerar - godkända läkemedel. January 2013. [cited 2017 Feb 27]. Available from: https://lakemedelsverket.se/upload/foretag/humanlakemedel/godkannandelistor/g01_2013.pdf.

- Oelke M, Speakman MJ, Desgrandchamps F, et al. Acute urinary retention rates in the general male population and in adult men with lower urinary tract symptoms participating in pharmacotherapy trials: a literature review. Urology. 2015;86:654–665.

- Kaplan SA, Walmsley K, Te AE. Tolterodine extended release attenuates lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2005;174:2273–2275.

- Roehrborn CG, Abrams P, Rovner ES, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of tolterodine extended-release in men with overactive bladder and urgency urinary incontinence. BJU Int. 2006;97:1003–1006.

- Abrams P, Kaplan S, De Koning Gans HJ, et al. Safety and tolerability of tolterodine for the treatment of overactive bladder in men with bladder outlet obstruction. J Urol. 2006;175:999–1004.

- Kaplan SA, Roehrborn CG, Dmochowski R, et al. Tolterodine extended release improves overactive bladder symptoms in men with overactive bladder and nocturia. Urology. 2006;68:328–332.

- Kosilov K, Loparev S, Ivanovskaya M, et al. Additional correction of OAB symptoms by two anti-muscarinics for men over 50 years old with residual symptoms of moderate prostatic obstruction after treatment with tamsulosin. Aging Male. 2015;18:44–48.

- Lee KW, Hur KJ, Kim SH, et al. Initial use of high-dose anticholinergics combined with alpha-blockers for male lower urinary tract symptoms with overactive bladder: a prospective, randomized preliminary study. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2016. [Epub ahead of print]. doi:10.1111/luts.12124

- Matsukawa Y, Takai S, Funahashi Y, et al. Long-term efficacy of a combination therapy with an anticholinergic agent and an alpha1-blocker for patients with benign prostatic enlargement complaining both voiding and overactive bladder symptoms: a randomized, prospective, comparative trial using a urodynamic study. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017;36:748–754.

- Yamanishi T, Asakura H, Seki N, Tokunaga S. Efficacy and safety of combination therapy with tamsulosin, dutasteride and imidafenacin for the management of overactive bladder symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: a multicenter, randomized, open-label, controlled trial (DIrecT Study). Int J Urol. 2017;24:525–531.

- European Association of Urology. Treatment of non-neurogenic male LUTS. 2017. [cited 2017 Feb 18]. Available from: http://uroweb.org/guideline/treatment-of-non-neurogenic-male-luts

- Blasco P, Valdivia MI, Ona MR, et al. Clinical characteristics, beliefs, and coping strategies among older patients with overactive bladder. Neurourol Urodyn. 2017:36:774–779.

- Kinsey D, Pretorius S, Glover L, et al. The psychological impact of overactive bladder: a systematic review. J Health Psychol. 2016;21:69–81.

- McVary KT, Peterson A, Donatucci CF, et al. Use of structural equation modeling to demonstrate the differential impact of storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms on symptom bother and quality of life during treatment for lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2016;196:824–830.

- Agarwal A, Eryuzlu LN, Cartwright R, et al. What is the most bothersome lower urinary tract symptom? Individual- and population-level perspectives for both men and women. Eur Urol. 2014;65:1211–1217.

- Chapple CR, Kelleher CJ, Evans CJ, et al. A narrative review of patient-reported outcomes in overactive bladder: what is the way of the future? Eur Urol. 2016;70:799–805.

- Van Kerrebroeck P, Haab F, Angulo JC, et al. Efficacy and safety of solifenacin plus tamsulosin OCAS in men with voiding and storage lower urinary tract symptoms: results from a phase 2, dose-finding study (SATURN). Eur Urol. 2013;64:398–407.

- Obata J, Matsumoto K, Yamanaka H, et al. Who would benefit from solifenacin add-on therapy to tamsulosin for overactive bladder symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia? Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2013;5:145–149.

- Masumori N, Tsukamoto T, Yanase M, et al. The add-on effect of solifenacin for patients with remaining overactive bladder after treatment with tamsulosin for lower urinary tract symptoms suggestive of benign prostatic obstruction. Adv Urol. 2010; Article ID 205251.

- van Kerrebroeck P, Chapple C, Drogendijk T, et al. Combination therapy with solifenacin and tamsulosin oral controlled absorption system in a single tablet for lower urinary tract symptoms in men: efficacy and safety results from the randomised controlled NEPTUNE trial. Eur Urol. 2013;64:1003–1012.

- Drake MJ, Chapple C, Sokol R, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of single-tablet combinations of solifenacin and tamsulosin oral controlled absorption system in men with storage and voiding lower urinary tract symptoms: results from the NEPTUNE Study and NEPTUNE II open-label extension. Eur Urol. 2015;67:262–270.

- Cardozo L, Lisec M, Millard R, et al. Randomized, double-blind placebo controlled trial of the once daily antimuscarinic agent solifenacin succinate in patients with overactive bladder. J Urol. 2004;172:1919–1924.

- Chapple CR, Rechberger T, Al-Shukri S, et al. Randomized, double-blind placebo- and tolterodine-controlled trial of the once-daily antimuscarinic agent solifenacin in patients with symptomatic overactive bladder. BJU Int. 2004;93:303–310.

- Haab F, Cardozo L, Chapple C, et al. Long-term open-label solifenacin treatment associated with persistence with therapy in patients with overactive bladder syndrome. Eur Urol. 2005;47:376–384.

- Brostrom S, Hallas J. Persistence of antimuscarinic drug use. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:309–314.

- Hakimi Z, Johnson M, Nazir J, et al. Drug treatment patterns for the management of men with lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia who have both storage and voiding symptoms: a study using the health improvement network UK primary care data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31:43–50.

- Veenboer PW, Bosch JL. Long-term adherence to antimuscarinic therapy in everyday practice: a systematic review. J Urol. 2014;191:1003–1008.

- Sussman D, Garely A. Treatment of overactive bladder with once-daily extended-release tolterodine or oxybutynin: the antimuscarinic clinical effectiveness trial (ACET). Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;18:177–184.

- Landis JR, Kaplan S, Swift S, et al. Efficacy of antimuscarinic therapy for overactive bladder with varying degrees of incontinence severity. J Urol. 2004;171:752–756.

- Abrams P, Larsson G, Chapple C, et al. Factors involved in the success of antimuscarinic treatment. BJU Int. 1999;83 Suppl 2:42–47.