Abstract

Erectile dysfunction is a common disease characterized by endothelial dysfunction. The aetiology of ED is often multifactorial but evidence is being accumulated in favor of the proper function of the vascular endothelium that is essential to achieving and maintaining penile erection. Uric acid itself causes endothelial dysfunction via decreased nitric oxide production. This study aims to evaluate the serum uric acid (SUA) levels in 180 ED patients, diagnosed with the International Index of Erectile Function-5 (IIEF-5) and 30 non-ED control. Serum uric acid was analyzed with a commercially available kit using ModularEVO (Roche, Monza, Italy). Within-assay and between-assay variations were 3.0% and 6.0%, respectively. Out of the ED patients, 85 were classified as arteriogenic (A-ED) and 95 as non-arteriogenic (NA-ED) with penile-echo-color-Doppler. Uric acid levels (median and range in mg/dL) in A-ED patients (5.8, 4.3–7.5) were significantly higher (p < .001) than in NA-ED patients (4.4, 2.6–5.9) and in control group (4.6, 3.1–7.2). There was a significant difference (p < .001) between uric acid levels in patients with mild A-ED (IIEF-5 16–20) and severe/complete A-ED (IIEF-5 ≤ 10) that were 5.4 (range 4.3–6.5) mg/dL and 6.8 (range 6.4–7.2) mg/dL, respectively. There was no difference between the levels of uric acid in patients with different degree of NA-ED. Our findings reveal that SUA is a marker of ED but only of ED of arteriogenic aetiology.

Introduction

Erectile dysfunction (ED), defined as the persistent inability to reach or maintain penile erection sufficient for a satisfactory sexual performance, is a frequent disorder involving a growing number of old men [Citation1]. However, the age is not a limiting factor for ED medical management [Citation2,Citation3]. In fact, the aetiology of ED is often multifactorial, with lifestyle, neurologic, hormonal, vascular, and psychological factors playing a role [Citation4,Citation5].

Over the two last decades, many data have been published demonstrating a linear relationship between ED and the severity of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). A vicious cycle of increased uneasiness, growing mental stress, inter-personal problems, LUTS secondary to BPH and ED is initiated having a significant negative impact on the quality of the life [Citation6]. Tadalafil has been demonstrated to be effective to improve vessels elasticity and, as consequence, male LUTS symptoms associated with BPH [Citation7].

Evidence is being accumulated in favor of the proper function of the vascular endothelium that is essential to achieving and maintaining penile erection. In fact, recent data reveal more than 80% of ED has an organic basis, with vascular disease being the most common aetiology [Citation8]. A functioning nitric oxide (NO) pathway is a primary determinant of smooth muscle tone, arterial inflow, and restricted venous outflow in the physiology of erection. Disruption of any of these factors can lead to ED. In conditions of increased oxidative stress and atherosclerosis with complicated metabolic status, often characterized by overweight and obesity associated to sexual hormone alteration, the progressive endothelial dysfunction is a common pathogenetic feature [Citation9,Citation10].

A close relationship between testosterone (T) and ED has been demonstrated in late-onset hypogonadism (LOH). LOH, diagnosed when declining T concentrations in the aging male, is also associated with reduced bone density, muscle strength, increased visceral obesity, insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome. In this case, T replacement treatment (TRT) resulted in an efficient therapy for hypogonadal men to improve health-related quality of life, ED and LUTS [Citation11,Citation12]. But testosterone withdrawal leads to loss of treatment improvements like improvements in obesity, LUTS, ED and quality of life: a continued treatment is required to maintain the associated benefits even in men suffering from type 1 diabetes mellitus [Citation13–15]. Serum uric acid (SUA) is associated with endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation, and is now beginning to be considered a risk predictor for cardiovascular disease. Park et al. [Citation16] found that SUA attenuated NO production. Phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors (iPDE5) enhance NO activity and are currently the most effective oral drugs for the treatment of male ED. In fact, glycemic control and lifestyle changes are not solely adequate for a better sexual function in ED due to diabetes and iPDE5 should be used additionally [Citation17]. Also, Matheus et al. [Citation18] reported that SUA levels were reversely correlated with the microvascular vasodilator response to acetylcholine in type 1 diabetes. Based on the literature, it seems that there is a possible relationship between SUA and ED. The main hypothesis of this study is that increased SUA levels may be related to ED subjects and particularly to ED subjects of atherosclerotic aetiology.

Materials and methods

Investigation protocol

In our center, patients complaining of ED are currently investigated by careful history-taking and clinical andrological examination; then, a few days later, by a panel of examinations, including blood tests, complete blood picture, glycated, glucose, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol, uric acid, transaminases, testosterone, prolactin, 17-β-estradiol and the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) questionnaire and echo-colour-Doppler of both cavernous arteries. The IIEF questionnaire is a validated, self-administered tool [Citation19], but we only evaluated the answers to the first five (erectile response dominium, IIEF-5) of the 15 questions. Possible scores for the IIEF-5 range from 0 to 25; scores of 22–25 indicate normal erectile function whereas scores of 21 or below indicate ED (mild 16–20, moderate 11–15, severe 5–10, complete ≤4). Penile echo-colour-Doppler was performed in basal conditions and after an intracavernous injection of 10 μg prostaglandin E1 (PgE1) [Citation20], and the peak systolic velocity (PSV) and end-diastolic velocity (EDV) were recorded at 5, 10, 15, 20 and 25 min after the injection in the proximal portion of the penis. To recognize the aetiology of ED, all patients were studied with eco-colour-Doppler and were classified as “arteriogenic” (A-ED) when their PSV was <25 cm/s and “non-arteriogenic” (NA-ED) when their PSV was ≥35 cm/s, or ≤35 cm/s but >25 cm/s with concomitant EDV ≤0 cm/s [Citation20]. If a patient appeared stressed, he was given a second injection of the same dose of PgE1 and all measurements were repeated. The erection quality was estimated 20 min after each injection. From 30 to 60 min before the penile echo-colour-Doppler, participants were placed in a supine position and blood samples were drawn from a cubital vein into EDTA tubes. Samples were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The serum was separated and stored at –80 °C until analysis. Between the phlebotomy and the storage at –80 °C passed no more than 60 min.

Subjects

One hundred and eighty patients affected for at least 10 months by ED were recruited from our andrology outpatients clinic and included in this study. A second group of 30 men non-ED, matched for age, was also investigated. The exclusion criteria were age less than 25 years and over 50 years, hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg in three consecutive recordings at rest), kidney diseases, reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR <60), severe retinopathy, liver failure, pancreatic diseases [Citation21], infection diseases, coronary heart disease, peripheral or cerebrovascular disease, diabetic or nondiabetic neuropathy, autoimmune and degenerative neurologic disorders [Citation22], endocrine diseases, gout, pelvic surgery, prostatic diseases, drug or alcohol abuse, testes hypertrophy, significant penile deformity, previous or current treatment of ED, vitamins and testosterone supplementation and major psychiatric disorders. We also excluded subjects with disorders of gastrointestinal tract because uric acid levels can rise markedly in the fluid that accumulate in the ileal lumen in response to infection [Citation23,Citation24]. Subjects taking ivabradine to decrease heart rate were also excluded from the study [Citation25]. The patients of the two ED subgroups and the controls declared normal physical activity [Citation26] and not to take statins. For all recruited patients, age, cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, full medical and sexual history and current therapy were recorded. A physical examination was also performed to obtain data on weight, blood pressure, peripheral pulses, genitals and neurologic state. Patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria were asked to complete the IIEF-5.

This investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Signed informed written consent was obtained from all subjects before their participation in the study. No ethical committee approval was required because no additional blood was needed for this study and this was explained thoroughly to all patients who gave their written informed consent also for laboratory tests and also because this procedure has been reported to be acceptable [Citation27].

Assays

HbA1c was measured using a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method (Bio-Rad, Segrate, Italy). Serum glucose, creatinine, total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol, uric acid, ALT, AST, testosterone, prolactin, and 17-β-estradiol were analyzed with commercially available kits using ModularEVO (Roche, Monza, Italy). Plasma LDL-cholesterol was calculated with the use of Friedewald’s formula. Glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated by using the Cockroft–Gault equation. Within-assay and between-assay variations for all the analytes were <3.0% and <6.0%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as median and range or absolute number and the relative frequency. For statistical analysis, the Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare data between the groups. p values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were carried out by using the SPSS 13.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

The characteristics of the arteriogenic and nonarteriogenic ED patients are summarized in . Out of the 180 males, based on the echo-colour-Doppler examination results, 85 patients had arteriogenic (median age 44 years, range 29–49 years; median BMI 23.6 kg/m2, range 21.2–26.3 kg/m2) and 95 patients had non-arteriogenic ED (median age 45 years, range 31–50 years; median BMI 22.9 kg/m2, range 19.9–25.9 kg/m2). The age and the BMI of the two groups were not significantly different (p> .05). Median PSV was 16 cm/s (range 7–20 cm/s) and 43 cm/s (range 32–83 cm/s) in patients with arteriogenic and with nonarteriogenic ED (p < .001), respectively. Median EDV was 4.2 cm/s (range 0–6 cm/s) and 2.2 cm/s (range from −5 to +13 cm/s) in patients with arteriogenic and with nonarteriogenic ED (p < .002), respectively. Median RI was 0.72 (range 0.63–0.79) and 0.95 (range 0.73–1.2) in patients with arteriogenic and with nonarteriogenic ED (p = .001), respectively. In the first group, IIEF values were: median 9 (range 1–15); in the second group, the respective figures were median 15 (range 2–23). There was significant difference between the two groups (p < .02). The degree of ED was classified in A-ED patients as severe/complete in 11 patients (13%), as moderate in 42 (50%) and as mild in 32 (37%); in NA-ED patients as severe/complete in nine patients (10%), as moderate in 35 (37%) and as mild in 51 (53%).

Table 1. Clinical and laboratory features of patients with erectile dysfunction.

Regardless of aetiology of ED, the median uric acid level was 5.1 (range 2.6–7.5) mg/dL in the ED patients and 4.6 (range 3.1–7.2) mg/dL in control group. There were no differences neither between ED patients and controls nor between the two ED subgroups regarding all other laboratory tests (p > .05). Hormonal status of all patients was in the normal range.

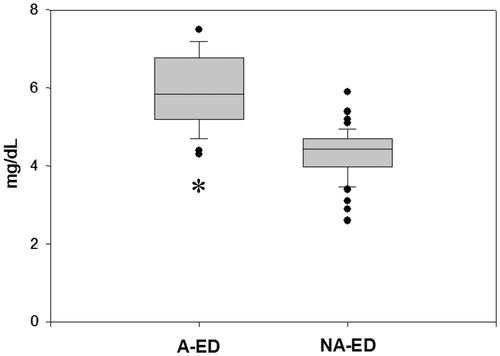

Uric acid levels in A-ED patients (5.8, range 4.3–7.5 mg/dL) were significantly higher (p < .001) than in NA-ED patients (4.4, range 2.6–5.9 mg/dL) () and in the control group (4.6, range 3.1–7.2 mg/dL). No difference (p > .50) was observed between the levels of uric acid in NA-ED and in controls. Besides, there was a significant difference (p < .001) between uric acid levels in patients with IIEF-5 16–20 (mild A-ED) and IIEF-5 ≤ 10 (severe/complete A-ED) that were 5.4 (range 4.3–6.5) mg/dL and 6.8 (range 6.4–7.2) mg/dL, respectively. We did not find any difference between the levels of uric acid in patients with different degree of NA-ED.

Figure 1. Uric acid concentrations in men with ED-AR and NA-ED. A-ED: arteriogenic erectile dysfunction; NA-ED: non-arteriogenic erectile dysfunction. *p < .001 vs. NA-ED. The upper and the lower limits of the boxes and the horizontal line within the boxes indicate the 75th and 25th percentiles and the median, respectively. The whisker caps indicate the 90th and 10th percentiles. Asterisk indicates statistical significance.

Discussion

Hyperuricemia is defined as a SUA concentration of >7.7 mg/dL in males or >6.6 mg/dL in females. The prevalence of hyperuricemia was 21.6–34.5% in males and 5.8–11.6% in females [Citation28]. Male gout patients usually complain of ED [Citation29]. After adjusting for risk factors such as aging, smoking, hypertension, obesity and diabetes, SUA concentration is indicated as one of the risk factor of ED: increasing by 1 mg/dL doubled the incidence rate of ED [Citation30]. The populations studied, ED and controls, were homogeneous with similar patterns of metabolic variables. Our subjects were men still young, not affected with LOH and with normal concentration of T [Citation11,Citation12]. The patients of the two groups, ED and non-ED, declared not to take T and not to have taken T before, for any reasons [Citation31]. It is generally accepted that ED has been associated with advanced artheriosclerotic CAD [Citation32,Citation33]. Therefore, the subjects with clinical history of CAD and/or with atherosclerotic risk factors were excluded from the study [Citation34]. As uric acid has been associated with characteristics of the metabolic syndrome and with kidney insufficiency (eGFR < 60), only subjects without those characteristics were included in our study.

In this study of well-characterized ED patients, in particular as regards the penile arteriogenic and non-arteriogenic aetiology, we found a significant increase of uric acid concentrations in the A-ED subgroups compared with healthy controls (p < .001) and compared with NA-ED (p < .001) even if all the levels were in the reference range. Solak et al. [Citation35] did not show the acid uric impact on sexual function. However, the ED population were not divided according to the aetiology in A-ED and NA-ED. On the contrary, our findings confirm Salem et al. that found higher uric acid concentration in 251 ED than in 252 non-ED controls (p < .001). Also in this study, the population was not described in detail and particularly the aetiology of ED patients, vascular (A-ED or NA-ED) or psychogenic, was not reported [Citation30]. Next, we evaluated the relation between the degree of ED and SUA level and we found that the higher the concentration, the more severe only the A-ED. The same relation do not keep for NA-ED.

Although, it was previously thought that uric acid was a major antioxidant and had possible beneficial antiatherosclerotic effects, it has been demonstrated that it is a risk factor for atherosclerosis and related diseases [Citation36]. It appears that uric acid can potentially reduce NO in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle by various mechanisms, including direct scavenging, stimulation of arginase and induction of oxidative stress [Citation37–39]. We found a significant increase of ROM plasma levels and a simultaneous significant decrease of plasma TAS concentration in A-ED subjects compared to NA-ED subjects, indicating the presence of an imbalance between pro-oxidant and the protective mechanisms conferred by antioxidants only in A-ED patients [Citation8]. Recent studies have suggested that a relationship could exist between 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] deficiency and ED both in normal subject and in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [Citation27,Citation40]. Uric acid can also induce microvascular disease by stimulating vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation [Citation39,Citation41,Citation42]. The relaxation of cavernous smooth musculature and the smooth muscles of the arterial walls has a pivotal role in the erectile process. NO is also one of the key mediators in the relaxation of these smooth muscles [Citation43]. In addition, hyperuricemia is strongly associated with endothelial dysfunction in humans, including in asymptomatic hyperuricemia [Citation44]. Many authors have shown that lowering SUA with xanthine oxidase inhibitors can improve endothelial dysfunction [Citation45–48]. Therefore, to determine the exact role of uric acid and ED, prospective randomized clinical trials are required to investigate whether a reduction in SUA concentration can prevent A-ED.

In conclusion, the present study indicates that uric acid is increased in ED patient but only in those of arteriogenic aetiology. The observation that uric acid may have a role in driving endothelial dysfunction and microvascular disease provides a potential causal link between uric acid and A-ED [Citation40,Citation49]. The mechanisms of uric acid-related ED remained uncertain, we speculate that uric acid may cause ED via endothelial dysfunction but we did not assess flow-mediated dilation and other marker of endothelial functions. Therefore, future investigations are needed, examining definitive mechanisms of ED in these subjects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Kaya E, Sikka SC, Kadowitz PJ, et al. Aging and sexual health: getting to the problem. Aging Male. 2017;20:65–80.

- Samipoor F, Pakseresht S, Rezasoltani P, et al. Awareness and experience of andropause symptoms in men referring to health centers: a cross-sectional study in Iran. Aging Male. 2017;20:153–160.

- Goh WH, Hart WG. Association of general and abdominal obesity with age, endocrine and metabolic factors in Asian men. Aging Male. 2016;19:27–33.

- Lue TF. Erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1802–1813.

- Paroni R, Barassi A, Ciociola F, et al. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), symmetric dimethylarginine (SDMA) and l-arginine in patients with arteriogenic and non-arteriogenic erectile dysfunction. Int J Androl. 2012;35:660–667.

- Yassin A, Saad F, Hoesl CS, et al. Alpha-adrenoceptors are a common denominator in the pathophysiology of erectile function and BPH/LUTS – implications for clinical practice. Andrologia. 2006;38:1–12.

- Amano T, Earle C, Imao T, et al. Administration of daily 5 mg tadalafil improves endothelial function in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Aging Male. 2017;22:1–6.

- Kendirci M, Trost L, Sikka SC, et al. The effect of vascular risk factors on penile vascular status in men with erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2007;178:2516–2520.

- Barassi A, Colpi GM, Piediferro G, et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant status in patients with erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2009;6:2820–2825.

- Dozio E, Barassi A, Dogliotti G, et al. Adipokines, hormonal parameters, and cardiovascular risk factors: similarities and differences between patients with erectile dysfunction of arteriogenic and nonarteriogenic origin. Sex Med. 2012;9:2370–2377.

- Yassin A, Doros G. Testosterone therapy in hypogonadal men results in sustained and clinically meaningful weight loss. Clin Obes. 2013;3:73–83.

- Yassin D-J, Doros G, Hammerer PG, et al. Long-term testosterone treatment in elderly men with hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction reduces obesity parameters and improves metabolic syndrome and health-related quality of life. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1567–1576.

- Yassin A, Nettleship J, Talib RA, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement therapy withdrawal and re-treatment in hypogonadal elderly men upon obesity, voiding function and prostate safety parameters. Aging Male. 2016;19:64–69.

- Saad F, Yassin A, Almehmadi Y, et al. Effects of long-term testosterone replacement therapy, with a temporary intermission, on glycemic control of nine hypogonadal men with type 1 diabetes mellitus – a series of case reports. Aging Male. 2015;18:164–168.

- Salman M, Yassin D-J, Shoukfeh H, et al. Early weight loss predicts the reduction of obesity in men with erectile dysfunction and hypogonadism undergoing long-term testosterone replacement therapy. Aging Male. 2017;20:45–48.

- Park JH, Jin YM, Hwang S, et al. Uric acid attenuates nitric oxide production by decreasing the interaction between endothelial nitric oxide synthase and calmodulin in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: a mechanism for uric acid-induced cardiovascular disease development. Nitric Oxide. 2013;32:36–42.

- Kirilmaz U, Guzel O, Aslan Y, et al. The effect of lifestyle modification and glycemic control on the efficacy of sildenafil citrate in patients with erectile dysfunction due to type-2 diabetes mellitus. Aging Male. 2015;18:244–248.

- Matheus AS1, Tibiriçá E, da Silva PB, et al. Uric acid levels are associated with microvascular endothelial dysfunction in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2011;28:1188–1193.

- Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319–326.

- Aversa A, Bruzziches R, Spera G. Diagnosing erectile dysfunction: the penile dynamic colour duplex ultrasound revisited. Int J Androl. 2005;28:61–63.

- Pezzilli R, Corsi MM, Barassi A, et al. Serum adhesion molecules in acute pancreatitis: time course and early assessment of disease severity. Pancreas. 2008;37:36–41.

- Dozio E, Barassi A, Dogliotti G, et al. Comment on: adipokines, hormonal parameters, and cardiovascular risk factors: similarities and differences between patients with erectile dysfunction of arteriogenic and nonarteriogenic origin. J Sex Med. 2013;10:613.

- Crane JK, Mongiardo KM. Pro-inflammatory effects of uric acid in the gastrointestinal tract. Immunol Invest. 2014;43:255–266.

- Salvatore S, Finazzi S, Barassi A, et al. Low fecal elastase: potentially related to transient small bowel damage resulting from enteric pathogens. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:392–396.

- Mert KU, Dural M, Mert GO, et al. Effects of heart rate reduction with ivabradine on the international ındex of erectile function (IIEF-5) in patients with heart failure. Aging Male. 2017;26:1–6.

- Paunksnis AL, Evangelista MR, La Scala Teixeira CV, et al. Metabolic and hormonal responses to different resistance training systems in elderly men. Aging Male. 2017;22:1–5.

- Barassi A, Pezzilli R, Colpi GM, et al. Vitamin D and erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2014;11:2792–2800.

- Long H, Jiang J, Xia J, et al. Hyperuricemia is an independent risk factor for erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2016;13:1056–1062.

- Schlesinger N, Radvanski DC, Cheng JQ, et al. Erectile dysfunction is common among patients with gout. J Rheumatol. 2015;42:1893–1897.

- Salem S, Mehrsai A, Heydari R, et al. Serum uric acid as a risk predictor for erectile dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1118–1124.

- Yassin AA, Almehmadi Y, Saad F, et al. Effects of intermission and resumption of long-term testosterone replacement therapy on body weight and metabolic parameters in hypogonadal in middle-aged and elderly men. Clin Endocrinol. 2016;84:107–114.

- Solomon H, Man JW, Jackson G. Erectile dysfunction and the cardiovascular patient: endothelial dysfunction is the common denominator. Heart. 2003; 89:251–253.

- Almehmadi Y, Yassin D-J, Yassin AA. Erectile dysfunction is a prognostic indicator of comorbidities in men with late onset hypogonadism. Aging Male. 2015;18:186–194.

- Barassi A, Pezzilli R, Morselli-Labate AM, et al. Evaluation of high sensitive troponin in erectile dysfunction. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:548951.

- Solak Y, Akilli H, Kayrak M, et al. Uric acid level and erectile dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. J Sex Med. 2014;11:165–172.

- Puddu P, Puddu GM, Cravero E, et al. Relationships among hyperuricemia, endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. J Cardiol. 2012;59:235–242.

- Sánchez-Lozada LG, Soto V, Tapia E, et al. Role of oxidative stress in the renal abnormalities induced by experimental hyperuricemia. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;295:F1134–F1141.

- Zharikov S, Krotova K, Hu H, et al. Uric acid decreases NO production and increases arginase activity in cultured pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1183–C1190.

- Barassi A, Corsi Romanelli MM, Pezzilli R, et al. Levels of l-arginine and l-citrulline in patients with erectile dysfunction of different aetiology. Andrology. 2017;5:256–261.

- Basat S, Sivritepe R, Ortaboz D, et al. The relationship between vitamin D level and erectile dysfunction in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aging Male. 2017;23:1–5.

- Corry DB, Eslami P, Yamamoto K, et al. Uric acid stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and oxidative stress via the vascular renin–angiotensin system. J Hypertens. 2008;26:269–275.

- Kanbay M, Sánchez-Lozada LG, Franco M, et al. Microvascular disease and its role in the brain and cardiovascular system: a potential role for uric acid as a cardiorenal toxin. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26:430–437.

- Dean RC, Lue TF. Physiology of penile erection and pathophysiology of erectile dysfunction. Urol Clin N Am. 2005;32:379–395.

- Erdogan D, Gullu H, Caliskan M, et al. Relationship of serum uric acid to measures of endothelial function and atherosclerosis in healthy adults. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:1276–1282.

- Butler R, Morris AD, Belch JJ, et al. Allopurinol normalizes endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetics with mild hypertension. Hypertension. 2000;35:746–751.

- Farquharson CA, Butler R, Hill A, et al. Allopurinol improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2002;106:221–226.

- Kanbay M, Huddam B, Azak A, et al. A randomized study of allopurinol on endothelial function and estimated glomular filtration rate in asymptomatic hyperuricemic subjects with normal renal function. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1887–1894.

- Guthikonda S, Sinkey C, Barenz T, et al. Xanthine oxidase inhibition reverses endothelial dysfunction in heavy smokers. Circulation. 2003;107:416–421.

- Grayson PC, Kim SY, LaValley M, et al. Hyperuricemia and incident hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63:102–110.