Abstract

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is very common in aging men and causes lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), which decrease health-related quality of life. A number of evidence suggests that other than ageing, modifiable factors, such as increasing prostate volume, obesity, diet, dyslipidemia, hormonal imbalance, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, alcohol, and smoking, also contribute to the development of BPH and/or LUTS. More recently, erectile dysfunction (ED) has been linked to LUTS/BPH as a part of this syndrome, suggesting that patients with BPH or LUTS easily develop ED, and that LUTS/BPH symptoms often coexist with ED. This article focuses on the epidemiology and risk factors of the combined phenotype LUTS/BPH – ED.

Introduction

The term erectile dysfunction (ED) is widely mentioned nowadays within both the medical professional and lay public communities, and many understand its basic meaning and reference to sexual dysfunction. However, its clinical implications are far more extensive and very likely less well understood.

The clinical condition, commonly referred to as ED, is accurately defined as the inability to attain and maintain a satisfactory erection of the penis to permit sexual intercourse sufficiently [Citation1]. Therefore, this definition is effective to establish the boundaries of the sexual dysfunction among a host of male sexual disorders. It is fair also to comprehend the term as a descriptive symptom, in acknowledgment that it portrays erection difficulty or inability without specific attribution to a medical disease. However, this sexual dysfunction is indisputably associated with underlying adverse health conditions and risk factors, and clinical evaluation is used to establish the apparent clinical association. Current biomedical advances in sexual medicine affirm its real pathophysiologic basis and support its strong links with clinical health and disease. Moreover, beyond its multiple associations with health co-morbidities, ED appears also to carry long-term health risks and adversely influence survival.

Men who recognize a defect in their ability to achieve an erection might not immediately recognize that ED is the problem. The quality of man’s erections deteriorates gradually over time. Consequently, men may be uncertain whether their erectile difficulties are permanent or temporary [Citation2] and may wait to see if ED resolves on its own [Citation3]. The most frequent reasons for such passiveness are the belief that lack of complete erection was part of a normal aging, sexual inactivity caused by widowhood, lack of perception of ED as a medical disorder, ashamed to talk with a physician about sexuality. Moreover, the stigma or embarrassment of having ED may lead to denial of the problem. For these issues, the incidence of ED is often undervalued. This problem is further increased by a bad clinical practice, in which specialists or general practitioners do not investigate sexual habits while managing other conditions. Many men with risk factors associated with ED have ED, including those who had moderate or severe dysfunction; however, the awareness of these men of having ED is often low [Citation4]. Considering the impact that ED has on quality of life and that it may often respond to treatment, ED should be suspected and assessed in men with risk factors, such as cardiovascular disease or presence of cardiovascular risk factors, diabetes mellitus (DM), and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), regardless of their apparent level of awareness of ED [Citation4].

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) causes LUTS and approximately 70% of men with LUTS/BPH have co-existing ED [Citation5]. This prevalence ranges from about 35% to 95% and increases with LUTS severity [Citation6]. Often patients referring to clinician for LUTS/BPH are found to have ED and vice versa. The prevalence of coexisting LUTS and ED increases with age; the severity of one disease often correlates with the other, with most men who sought treatment for either LUTS or ED having both conditions [Citation7,Citation8].

LUTS/BPH and ED share similar risk factors, suggesting that the pathophysiology of LUTS and its underlying mechanisms may be similar to those of ED. Indeed, metabolic status, inflammation, and the hormonal setting may play a role in the pathogenesis of BPH [Citation9–15], as well as in ED [Citation16]. Accordingly, common therapeutic strategies are currently prospected for these two conditions [Citation17–24]. The main potential risk factors for LUTS/BPH and ED are discussed below.

Age

Nowadays, sexual activity has been reconsidered for aging men, and the concept of sex is different from the past. Sexual activity is more common among older men than before, being an important component of quality of life for aging men [Citation25]. The majority of men between the ages of 50 and 75 years report that they are sexually active, but many are bothered by sexual problems, including ED. Because of LUTS/BPH treatment-related sexual side effects and the known strong association between LUTS/BPH and ED, the effects of LUTS/BPH medical therapies on sexual function are an important consideration when selecting the most appropriate LUTS/BPH treatment and when monitoring men on LUTS/BPH treatment.

Sedentary lifestyle and lack of exercise

Many evidence support the central role of exercise in ameliorating both LUTS/BPH and ED. No daily walking is associated with more progressive LUTS than to stable or remitting LUTS [Citation26], and physical exercise at a level that can decrease low-grade clinical inflammation has been recognized as central factors influencing both vascular NO production and erectile function. Moreover, this lifestyle habit may have a role in reducing the burden of sexual dysfunction [Citation27]. It can be stated that moderate physical activity can have significant effects in improving erectile function as well as on serum testosterone levels. Therefore, as an independent risk factor, there may be a role for lifestyle measures to prevent progression or even enhance the regression of the earliest manifestations of ED, as well as to help stabilization or remission of LUTS/BPH.

Cigarette smoking

The past three decades have led to a compendium of evidence being compiled into the development of a relationship between cigarette smoking and ED. A positive dose–response relationship suggests that increased quantity and duration of smoking correlate with a higher risk of ED (dose-dependent and cumulative effect). The risk of ED is higher for smokers and ex-smokers than no-smokers, but this risk is higher for smokers than ex-smokers. It is possible that smoking cessation can lead to recovery of erectile function, but only if limited lifetime smoking exposure exists [Citation28].

Studies have shown that the increased risk of ED associated with smoking becomes statistically significant only after 20 pack-years or more (20 cigarettes/day for 1 year). The physiopathological mechanism that leads to ED involves decreased penile neuronal NOS expression, decreased endothelial integrity, and diminished smooth muscle content. Smoking has also been shown to impair endothelial NOS-mediated vascular dilation in young men.

In addition, to the vascular damage associated with tobacco smoking, some data suggest that it may lower testosterone levels [Citation29–31]. This effect may also explain the reported relationship between smoking and LUTS/BPH. Indeed, heavy smoking (defined as ≥50 pack-years) was found to increase the risk of LUTS exacerbation, and can affect storage and voiding symptoms. Subjects who smoked ≥50 pack-years in a lifetime had greater probability of severe deterioration of storage symptoms. Nicotine may increase sympathetic nervous system activity and could contribute to storage symptoms by increasing the tone of the bladder smooth muscle [Citation32,Citation33]. Furthermore, smoking could cause hormonal and nutrient imbalances affecting the bladder as well as collagen synthesis [Citation34]. It also affects bladder wall strength and detrusor instability [Citation35]. Therefore, it is mandatory to ask for smoking cessation in the combined phenotype LUTS/BPH – ED to increase chances of controlling both diseases.

Excessive alcohol intake

The role of alcohol in the development of LUTS/BPH – ED is more difficult to establish compared to other risk factors. The moderate consumption of alcohol may exert a protective effect on ED in the general population [Citation36,Citation37], but some studies have not confirmed this protective role. Population-based studies showed that low-alcohol consumption was predictor of ED [Citation38], and, among drinkers, the odds were lowest for consumption between 1 and 20 standard drinks per week [Citation22,Citation39]. In general, the overall findings are suggestive of alcohol consumption of a moderate quantity conferring the highest protection [Citation40]. The beneficial effects of alcohol on erectile function may be due, in part, to long-term benefits of alcohol on high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other variables that increase the bioavailability of NO.

Data on the association between LUTS/BPH and alcohol consumption are conflicting. While some studies have shown that alcohol consumption is associated with a decreased risk of BPH, others have not. Moreover, some studies have reported an association between alcohol and LUTS, but not BPH. Light drinking (less than one per day) may increase the likelihood of LUTS, whereas moderate-to-heavy drinking has shown no associations with LUTS. Urgency symptoms may be the exception, as they more likely occur among all alcohol drinkers. A review of studies concluded that daily drinking might increase the likelihood of LUTS, while decrease the risk of BPH [Citation41]. Indeed, one out of the two prospective studies examining LUTS found that daily drinking increased the risk of moderate-to-severe LUTS over a 4-year follow-up [Citation42], whereas the other showed that heavier drinking decreased the risk of high-moderate-to-severe LUTS or medically-treated BPH over 7 years [Citation43]. It is plausible that light alcohol intake increases LUTS by a diuretic effect or increasing sympathetic nervous system activity, while moderately-high alcohol intake decreases the risk of BPH and concurrent higher-severity LUTS by altering androgen levels [Citation44,Citation45]. More data are needed to establish how to advice patients with LUTS/BPH – ED regarding alcohol intake, but light alcohol consumption has not strong evidence to be denied.

Depression

The Massachusetts Male Aging Study (MMAS) showed that ED was associated with depressive symptoms after controlling for potential aging and para-aging confounders [Citation46]. ED is also associated with untreated and treated depressive symptoms. The association between ED and depression may be disorienting in clinical practice. Indeed, depression can be the consequence of or trigger for ED, as moderate or severe depressive mood or anti-depressant drug use may cause ED and ED independently may cause or exacerbate depressive mood [Citation47,Citation48].

This kind of bidirectional relationship has also been discovered for depression and LUTS/BPH: depression can be not only developing from the pathological condition of LUTS/BPH, but also be triggered or exacerbated by systemic inflammation, which is also associated with LUTS/BPH [Citation49,Citation50].

Hypertension and cardiovascular disease

Most men with hypothetic vasculogenic ED present at least one traditional cardiovascular risk factor [Citation51]. These evidences allowed the consideration of ED as a clinical manifestation of a functional (lack of vasodilation) or structural abnormality in penile circulation as component of a systemic vasculopathy. It is well known that ED may predict 5-years before the development of a major coronary event in 11% of ED cases; this, in terms of preventive medicine, means that ED could be considered equivalent to the coronary disease [Citation52].

The association between cardiovascular health and ED has not always been so clear in past years. One of the first studies to ask about sexual function among patients with hypertension was the classic TOMHS (The Treatment of Mild Hypertension Study) [Citation53] and its results contributed to the false belief that ED was rare in this population since they found only 12.2% of men referring any degree of sexual dysfunction at inclusion. TOMHS excluded subjects with comorbidities, such as DM or hyperlipidemia, older and moderate or severe hypertension. At the end of TOMHS, ED was more frequent among those patients using more antihypertensive drugs or with systolic blood pressure over 140 mmHg. Other trials also refuse the high prevalence of ED among patients with hypertension [Citation54] probably due to the characteristics of the sample and the method to diagnose ED.

Another issue relates to antihypertensive drugs and ED development, is an usual popular belief to blame medical therapy for hypertension as the main reason of ED, especially when there is a temporal coincidence between symptom initiation and the use of antihypertensive drugs, in particular when including the “old” diuretics and sz-blockers [Citation53]. In almost all trials where this topic was studied, ED was not the primary objective and was assessed by patient reports instead of questionnaire evaluation or measurement of penile rigidity. Therefore, there is a lack of definitive evidence even with sz-blocker and diuretics. Recently, a systematic analysis of trials concluded that only thiazide diuretics and sz-blockers, not including nebivolol, might influence erectile function. ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel antagonists were reported to have no relevant or even a positive effect on erectile function [Citation55].

Hypertension worsens also LUTS/BPH and may decrease the efficacy of α1-blockers, especially for the increased frequency and severity of storage symptoms [Citation56]. Moreover, men with hypertension are more likely to have a higher IPSS and large prostate volume than men without hypertension. This finding implicates a pathophysiological association between hypertension and LUTS, and the need to manage comorbid symptoms simultaneously [Citation57]. It is likely that hypertension plays a role in physiopathological mechanisms common to ED and LUTS/BPH, and focus on this modifiable risk factor is mandatory in clinical approach.

Hyperlipidemia

Epidemiologic data have confirmed that hyperlipidemia is a strong independent risk factor for the development of ED via endothelial damage and inflammation. Statins are first-line medical therapy for hyperlipidemia and protect the vascular endothelium. In fact, statins have been shown to improve endothelial function prior to altering lipid levels. Various meta-analyses have supported the conclusion that statins improve erectile function [Citation58].

Prostate synthesizes cholesterol at a level similar to the liver and accumulates it in a deposit within the gland in an age-dependent manner. More than 70 years ago, Swyer analyzed the cholesterol content in the prostate of BPH subjects and reported that its concentration was twice that in a normal prostate [Citation59]. Studies on the effect of dyslipidemia on prostate are heterogeneous, showing positive and negative association for circulating total and HDL-cholesterol, respectively, with prostate enlargement [Citation60]. However, other studies did not confirm the association. Many observations suggest that dyslipidemia per se is not sufficient to determine a LUTS/BPH phenotype, but the presence of other metabolic derangements, such as type 2 DM, favors the process, because of an unfavorable total and LDL-cholesterol particle size and density [Citation61].

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Diabetic patients have a well-known increased risk of developing ED, with prevalence ranging from 35% to 90%. In addition, patients with DM tend to develop ED 10–15 years earlier than the ED patients without DM. They appear to present with more severe ED and suffer a greater diminishment in health-related quality of life components than the general population. ED secondary to DM is more resistant to medical management with phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors (PDE5i). Moreover, poor glycemic control in patients with type II DM contributes significantly to the development and severity of ED.

Reactive oxygen species generated because of hyperglycemia impacts erectile function in multiple pathways. The chronic complications of macrovascular changes, microvascular changes, neuropathy, and endothelial dysfunction increase the odds that a diabetic man will develop ED. Furthermore, many patients with type II DM ultimately experience the negative impact of metabolic syndrome (MetS) on erectile function [Citation58].

The links between LUTS/BPH and glucose metabolism diseases were known since 1966 [Citation62]. Hyperinsulinaemia/glucose intolerance and type 2 DM have been considered as potential risk factors for BPH/LUTS based on several studies. Strong evidence correlates insulin levels and prostate volume, being the first an independent predictor of the second in symptomatic BPH patients aged over sixty [Citation60], and this association remains significant after adjusting for total testosterone, other metabolic factors, and blood pressure [Citation63]. These findings indicate that insulin is an independent risk factor for BPH, most probably stimulating prostate growth acting on IGF receptors. More studies are needed to establish a relation between glycaemic controls and control/worsening of LUTS/BPH.

Obesity/waist circumference

It is not easy to identify the sole contribution of obesity to the development of ED, as it is often coexistent with DM and hypertension. Nevertheless, data do suggest that it has an independent contribution to ED, being an independent predictor of ED. Weight loss in obese men is also associated with a regain of normal erectile function [Citation58]. In worldwide conducted studies, obesity – and in particular visceral obesity – is often comorbid with BPH. A recent meta-analysis, including 19 studies, reported a positive association between BMI and LUTS associated with BPH. Obesity can have a role even in early adulthood in determining a LUTS/BPH phenotype, as shown by a sonographic study conducted in 222 young men seeking medical care for couple infertility [Citation61,Citation64].

Hypogonadism

Testosterone is essential for erectile function. Literature has proven the necessity of androgens to maintain sufficient intracavernosal pressures and smooth muscle function to obtain an erection. The literature showing the role of testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) on erectile function is heterogeneous, and sometimes conflicting, showing positive correlation with erectile function or no improvement. It may be that the improvement in erectile function after TRT is transient, or that poor control of other modifiable risk factors for ED may have played a role against TRT. The recently published multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled Testosterone Trial study provides solid evidence that TRT has a positive impact on overall sexual function in men 65 years of age or older. This trial consisted of three separate studies: The Sexual Function Trial, the Physical Function Trial, and the Vitality Trial. The sexual function trial showed that sexual activity and sexual desire were increased. Men in the TRT group reported significantly increased international index of erectile function (IIEF) score with a mean improvement of 2.64 points. This provides sound evidence that treating hypogonadism can improve erectile function [Citation58].

The role of androgens in determining LUTS/BPH and the physiopathological ways that may lead to it are still a matter of debate. Although an increased androgen signaling is clearly implicated in the first two waves of prostate growth (the first one at birth, the second one at puberty – under the influence of increasing testosterone levels), its role in the third phase (starting at mid-late adulthood and involving selectively the periurethral zone), is not completely clear yet. In fact, a clear dose–response relationship between circulating androgen levels and BPH has never been demonstrated. In addition, during male senescence, androgens tend to decrease and not to increase. Several recent studies indicate that a low testosterone, more than a high one, might have a detrimental effect on prostate biology. In fact, LUTS can even be lessened by androgen supplementation in hypogonadal men [Citation65].

Recent data indicate that not only low testosterone but also high estradiol can favor BPH/LUTS progression. It is important to note that circulating testosterone is actively metabolized to estrogens and part of testosterone hormonal activity depends upon its binding to the estrogen receptors (ERs) that are present in both the prostate and bladder. In addition, the enzyme P450 aromatase that converts androgens to estrogens is highly expressed not only in fat tissue but also in the urogenital tract. Marmorston et al. showed an increased estrogen/androgen ratio almost half a century ago [Citation66] reporting that the estrogen/androgen ratio in 24-h urinary collections was elevated in men with BPH, as compared to normal controls. Many studies have reported a correlation between plasma 17β-estradiol levels and prostate volume or other features of LUTS/BPH, while others have not. The fear of clinicians to start a TRT on hypogonadal men with LUTS/BPH must be redefined based on this upcoming evidence [Citation65]. It is necessary to establish ways to determine which patients with LUTS/BPH, and even combined phenotype LUTS/BPH – ED, may benefit from TRT and in which terms; for this purpose, more studies are needed [Citation61].

Genetic predisposition

The underlying genetic mechanisms linked to LUTS/BPH are not fully known. Animal models have shown changes, often aging-related, in genes related to nervous control, vascularization of lower urinary tract, and smooth muscles, but these models have shown discrepancies between in-vitro and in-vivo studies. More can be added if these two models could be studied in the same animal [Citation67]. In addition, a correlation has been shown between inflammatory genes and LUTS/BPH. Genes involved in physiology of erectile function, as well as development of ED, also involve control of NOS genes encoding various types of neurotrophic factors, and K + channel genes; these have been proposed as targets for gene-based therapy when other treatments fail [Citation68]. Full comprehension of aberrant signaling pathways common to LUTS/BPH and ED could lead to a form of personalized medicine based on gene therapy [Citation69].

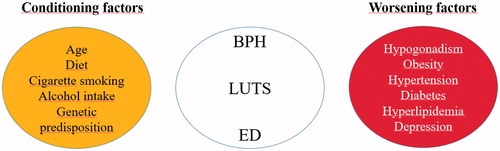

Protective factors include increased physical activity, increased vegetable consumption, and moderate alcohol intake [Citation70–72]. In particular, aerobic physical activity improves endothelial function and reduces the chronic inflammatory response; therefore, in association with a hypocaloric diet and pharmacological intervention should be considered in the practical management of this category of patients [Citation73]. summarizes the main conditioning and worsening factors of the LUTS.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Musicki B, Bella AJ, Bivalacqua TJ, et al. Basic science evidence for the link between erectile dysfunction and cardiometabolic dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2015;12:2233–2255.

- Pontin D, Porter T, McDonagh R. Investigating the effect of erectile dysfunction on the lives of men: a qualitative research study. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11:264–272.

- McCabe M, Matic H. Severity of ED: relationship to treatment-seeking and satisfaction with treatment using PDE5 inhibitors. J Sex Med. 2007;4:145–151.

- Shabsigh R, Kaufman J, Magee M, et al. Lack of awareness of erectile dysfunction in many men with risk factors for erectile dysfunction. BMC Urol. 2010;10:18.

- Rosen RC, Wei JT, Althof SE, et al. BPH registry and patient survey steering committee. Association of sexual dysfunction with lower urinary tract symptoms of BPH and BPH medical therapies: results from the BPH Registry. Urology. 2009;73:562–566.

- Ozayar A, Zumrutbas AE, Yaman O. The relationship between lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), diagnostic indicators of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), and erectile dysfunction in patients with moderate to severely symptomatic BPH. Int Urol Nephrol. 2008;40:933–939.

- Seftel AD, De la Rosette J, Birt J, et al. Coexisting lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction: a systematic review of epidemiological data. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:32–45.

- Singam P, Hong GE, Ho C, et al. Nocturia in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia: evaluating the significance of ageing, co-morbid illnesses, lifestyle and medical therapy in treatment outcome in real life practice. Aging Male. 2015;18:112–117.

- Park SG, Yeo JK, Cho DY, et al. Impact of metabolic status on the association of serum vitamin D with hypogonadism and lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic hyperplasia. Aging Male. 2017;17:1–5.

- Asiedu B, Anang Y, Nyarko A, et al. The role of sex steroid hormones in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Aging Male. 2017;20:17–22.

- Allen S, Aghajanyan I. Use of thermobalancing therapy in ageing male with benign prostatic hyperplasia with a focus on etiology and pathophysiology. Aging Male. 2017;20:28–32.

- Ren H, Li X, Cheng G, et al. The effects of ROS in prostatic stromal cells under hypoxic environment. Aging Male. 2015;18:84–88.

- Ferreira FT, Daltoé L, Succi G, et al. Relation between glycemic levels and low tract urinary symptoms in elderly. Aging Male. 2015;18:34–37.

- Kaplan SA, Lee JY, O'Neill EA, et al. Prevalence of low testosterone and its relationship to body mass index in older men with lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Aging Male. 2013;16:169–172.

- Kaplan SA, O'Neill E, Lowe R, et al. Prevalence of low testosterone in aging men with benign prostatic hyperplasia: data from the Proscar Long-term Efficacy and Safety Study (PLESS). Aging Male. 2013;16:48–51.

- Aktas BK, Gokkaya CS, Bulut S, et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on erectile dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms in benign prostatic hyperplasia patients. Aging Male. 2011;14:48–52.

- Amano T, Earle C, Imao T, et al. Administration of daily 5 mg tadalafil improves endothelial function in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Aging Male. 2017;22:1–6.

- Ko WJ, Han HH, Ham WS, et al. Daily use of sildenafil 50mg at night effectively ameliorates nocturia in patients with lower urinary tract symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia: an exploratory multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Aging Male. 2017;20:81–88.

- Favilla V, Russo GI, Privitera S, et al. Impact of combination therapy 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5-ARI) plus alpha-blockers (AB) on erectile dysfunction and decrease of libido in patients with LUTS/BPH: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Aging Male. 2016;19:175–181.

- Yassin A, Nettleship JE, Talib RA, et al. Effects of testosterone replacement therapy withdrawal and re-treatment in hypogonadal elderly men upon obesity, voiding function and prostate safety parameters. Aging Male. 2016;19:64–69.

- Kaufman JM. The effect of androgen supplementation therapy on the prostate. Aging Male. 2003;6:166–174.

- Haider KS, Haider A, Doros G, et al. Long-term testosterone therapy improves urinary and sexual function, and quality of life in men with hypogonadism: results from a propensity matched subgroup of a controlled registry study. J Urol. 2018;199:257–265.

- Kosilov K, Kuzina I, Kuznetsov V, et al. Cognitive functions and health-related quality of life in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia and symptoms of overactive bladder when treated with a combination of tamsulosin and solifenacin in a higher dosage. Aging Male. 2017;7:1–9.

- Henningsohn L, Kilany S, Svensson M, et al. Patient-perceived effectiveness and impact on quality of life of solifenacin in combination with an α-blocker in men with overactive bladder in Sweden: a non-interventional study. Aging Male. 2017;20:266–276.

- Rosen R, Carson C, Giuliano F. Sexual dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Eur Urol. 2005;47:824–837.

- Marshall LM, Holton KF, Parsons JK, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) Study Group, et al. Lifestyle and health factors associated with progressing and remitting trajectories of untreated lower urinary tract symptoms among elderly men. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2014;17:265–272.

- Esposito K, Giugliano F, Di Palo C, et al. Effect of lifestyle changes on erectile dysfunction in obese men: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:2978–2984.

- Shiyi C, Xiaoxu Y, Yunxia W, et al. Smoking and risk of erectile dysfunction: systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60443.

- Shaarawy M, Mahmoud KZ. Endocrine profile and semen characteristics in male smokers. Fertil Steril. 1982;38:255–257.

- Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Georgakopoulos D, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with dose-related and potentially reversible impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation in healthy young adults. Circulation. 1993;88:2149–2155.

- Huang YC, Chin CC, Chen CS, et al. Chronic cigarette smoking impairs erectile function through increased oxidative stress and apoptosis, decreased nNOS, endothelial and smooth muscle contents in a rat model. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140728.

- Narkiewicz K, Van de Borne PJ, Hausberg M, et al. Cigarette smoking increases sympathetic outflow in humans. Circulation. 1998;98:528–534.

- Rohrmann S, Crespo CJ, Weber JR, et al. Association of cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption and physical activity with lower urinary tract symptoms in older American men: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. BJU Int. 2005;96:77–82.

- Maserejian NN, Kupelian V, Miyasato G, et al. Are physical activity, smoking and alcohol consumption associated with lower urinary tract symptoms in men or women? Results from a population based observational study. J Urol. 2012;188:490–495.

- Knuutinen A, Kokkonen N, Risteli J, et al. Smoking affects collagen synthesis and extracellular matrix turnover in human skin. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:588–594.

- Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, et al. Sexual function in men older than 50 years of age: results from the health professionals follow-up study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:161–168.

- Kalter-Leibovici O, Wainstein J, Ziv A, et al. Clinical, socioeconomic, and lifestyle parameters associated with erectile dysfunction among diabetic men. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1739–1744.

- Martin SA, Atlantis E, Lange K, et al. Predictors of sexual dysfunction incidence and remission in men. J Sex Med. 2014;11:1136–1147.

- Chew KK, Bremner A, Stuckey B, et al. Alcohol consumption and male erectile dysfunction: an unfounded reputation for risk? J Sex Med. 2009;6:1386–1394.

- Cheng JY, Ng EM, Chen RY, et al. Alcohol consumption and erectile dysfunction: meta-analysis of population-based studies. Int J Impot Res. 2007;19:343–352.

- Parsons JK, Im R. Alcohol consumption is associated with a decreased risk of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2009;182:1463–1468.

- Wong SY, Woo J, Leung JC, et al. Depressive symptoms and lifestyle factors as risk factors of lower urinary tract symptoms in Southern Chinese men: a prospective study. Aging Male. 2010;13:113–119.

- Kristal AR, Arnold KB, Schenk JM, et al. Dietary patterns, supplement use, and the risk of symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:925–934.

- Eggleton MG. The diuretic action of alcohol in man. J Physiol (Lond). 1942;101:172–191.

- Van de Borne P, Mark AL, Montano N, et al. Effects of alcohol on sympathetic activity, hemodynamics, and chemoreflex sensitivity. Hypertension. 1997;29:1278–1283.

- Araujo AB, Durante R, Feldman HA, et al. The relationship between depressive symptoms and male erectile dysfunction: cross-sectional results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:458–465.

- Ahn TY, Park JK, Lee SW, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in Korean men: results of an epidemiological study. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1269–1276.

- Shiri R, Koskimäki J, Tammela TL, et al. Bidirectional relationship between depression and erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2007;177:669–673.

- Maes M, Yirmyia R, Noraberg J, et al. The inflammatory & neurodegenerative hypothesis of depression: leads for future research and new drug developments in depression. Metab Brain Dis. 2009;24:27–53.

- Hung SF, Chung SD, Kuo HC. Increased serum C-reactive protein level is associated with increased storage lower urinary tract symptoms in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85588.

- Kim SW, Paick JS, Park DW, et al. Potential predictors of asymptomatic ischemic heart disease in patients with vasculogenic erectile dysfunction. Urology. 2001;58:441–445.

- Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, et al. Erectile dysfunction and subsequent cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2005;294:2996–3002.

- Grimm RH Jr, Grandits GA, Prineas RJ, et al. Long-term effects on sexual function of five antihypertensive drugs and nutritional hygienic treatment in hypertensive men and women: treatment of mild hypertension study (TOMHS). Hypertension. 1997;29:8–14.

- Newman HF, Marcus H. Erectile dysfunction in diabetes and hypertension. Urology. 1985;26:135–137.

- Javaroni V, Neves MF. Erectile dysfunction and hypertension: impact on cardiovascular risk and treatment. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:627278.

- Ito H, Yoshiyasu T, Yamaguchi O, et al. Male lower urinary tract symptoms: hypertension as a risk factor for storage symptoms, but not voiding symptoms. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2012;4:68–72.

- Hwang EC, Kim SO, Nam DH, et al. Men with hypertension are more likely to have severe lower urinary tract symptoms and large prostate volume. Low Urin Tract Symptoms. 2015;7:32–36.

- DeLay KJ, Haney N, Hellstrom WJ. Modifying risk factors in the management of erectile dysfunction: a review. World J Mens Health. 2016;34:89–100.

- Swyer G. Cholesterol content of normal and enlarged prostates. Cancer Res. 1942;2:372–375.

- Nandeesha H, Koner BC, Dorairajan LN, et al. Hyperinsulinemia and dyslipidemia in non-diabetic benign prostatic hyperplasia. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;370:89–93.

- Corona G, Vignozzi L, Rastrelli G, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: a new metabolic disease of the aging male and its correlation with sexual dysfunctions. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;2014:329456.

- Bourke JB, Griffin JP. Diabetes mellitus in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. BMJ. 1968;4:492–493.

- Lotti F, Corona G, Vignozzi L, et al. Metabolic syndrome and prostate abnormalities in male subjects of infertile couples. Asian J Androl. 2014;16:295–304.

- Lotti F, Corona G, Colpi GM, et al. Elevated body mass index correlates with higher seminal plasma interleukin 8 levels and ultrasonographic abnormalities of the prostate in men attending an andrology clinic for infertility. J Endocrinol Investig. 2011;34:336–342.

- La Vignera S, Condorelli RA, Russo GI, et al. Endocrine control of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Andrology. 2016;4:404–411.

- Marmorston J, Lombardo LJ Jr, Myers SM, et al. Urinary excretion of estrone, estradiol and estriol by patients with prostatic cancer and benign prostate hypertrophy. J Urol. 1965;93:287–295.

- Kullmann FA, Birder LA, Andersson KE. Translational research and functional changes in voiding function in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2015;31:535–548.

- Yoshimura N, Kato R, Chancellor MB, et al. Gene therapy as future treatment of erectile dysfunction. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:1305–1314.

- Bechis SK, Otsetov AG, Ge R, et al. Personalized medicine for the management of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2014;192:16–23.

- Wei JT, Calhoun E, Jacobsen SJ. Urologic diseases in America project: benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2005;173:1256–1261.

- Parsons JK. Lifestyle factors, benign prostatic hyperplasia, and lower urinary tract symptoms. Curr Opin Urol. 2011;21:1–4.

- Park HJ, Won J, Sorsaburu S, et al. Urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) secondary to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and LUTS/BPH with erectile dysfunction in Asian men: a systematic review focusing on tadalafil. World J Mens Health. 2013;31:193–207.

- La Vignera S, Condorelli R, Vicari E, et al. Physical activity and erectile dysfunction in middle-aged men. J Androl. 2012;33:154–161.