Abstract

Objective: To develop a questionnaire for the differential diagnosis of detrusor underactivity (DUA) and bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) without performing invasive pressure flow studies.

Study design and methods: Symptoms of men with DUA were analyzed and compared with those of men with BOO using eight questions from the developing questionnaire. Patients with DUA have a bladder contractility index (PdetQmax+5xQmax) less than 100, whereas those with BOO have a BOO index (PdetQmax−2xQmax) greater than 40 in urodynamic studies (UDS). Men with detrusor overactivity in UDS and neurogenic issues were excluded from the analysis. One urologist reviewed patients’ medical records, and responded to eight questions without using information from UDS. Scores in the developing questionnaire were then compared to make a differential diagnosis between DUA and BOO.

Results: Overall, 318 men who underwent UDS were included. Symptoms were compared in patients diagnosed with DUA without BOO (n = 165) and BOO without DUA (n = 153). Questions 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7 were significantly different between groups. The sensitivity and specificity of the questionnaire were 95.8% and 95.4%, respectively, for predicting DUA in patients with scores greater than 45 points (cutoff value).

Conclusions: Men with DUA and BOO may be distinguished using a developing questionnaire without invasive evaluation. Men with scores greater than 45 points would be expected to have DUA but not BOO.

Introduction

Detrusor underactivity (DUA) is an increasingly popular topic of discussion, but its diagnosis and treatment still remain unclear. Estimates suggest that DUA is a prevalent, affecting 9–23% men older than 50 years, and as many as 48% of men older than 70 years [Citation1]. Although many think that they can recognize it, it remains impossible to diagnose the disease without an objective, yet invasive, urodynamic study (UDS). The American Urology Association (AUA) and International Continence Society (ICS) define patients with DUA based on contraction of reduce strength, duration resulting in prolonged bladder emptying, and/or failure to achieve complete bladder emptying within a usual span of time [Citation2,Citation3]. To the best of our knowledge, reduced strength, reduced duration, prolonged bladder emptying, and usual time span have not been defined. Furthermore, the differential diagnosis of patients with DUA and bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) in men with lower urinary tract symptom (LUTS) is a significant challenge without invasive evaluation in the clinic [Citation4]. Although decreased and weak urinary stream may present voiding dysfunction, uroflowmetry (UFM) does not help to distinguish these diseases. The UDS is the only gold standard for diagnosing and distinguishing patients with these diseases [Citation5]. However, UDS has significant drawbacks in the clinical setting, because it is invasive, expensive, and has associated morbidity. Recently, several studies have evaluated clinical data associated with DUA that may facilitate its diagnosis. These studies are very important because they may allow for the diagnosis of patients with DUA without using UDS, but using symptom-based assessments to distinguish them from patients with BOO [Citation6–8]. We assessed symptoms in men for a differential diagnosis between DUA and BOO to develop a DUA-symptom questionnaire (DUA-SQ).

Subjects and methods

We reviewed data from patients who underwent UDS between 2000 and 2016 in two tertiary medical centers (Konkuk University Medical Center and Asan Medical Center). Patients with detrusor overactivity in the UDS, acute urinary retention, or neurogenic problems, including stroke, Parkinson’s disease, spinal cord injury, and acute urinary tract infection were excluded from the analysis. All patients received detailed urological investigations including transrectal ultrasonography to measure prostate size, free flowmetry, postvoid residual urine (PVR), and UDS. Patients with DUA should have a bladder contractility index (BCI, defined as PdetQmax+5xQmax) less than 100, whereas those with BOO should have a BOO index (BOOI, defined as PdetQmax−2xQmax) greater than 40 in UDS. UDS was performed based on the recommendations of the ICS [Citation2]. UDS parameters of first sensation of filling, full sensation, cystometric bladder capacity, bladder compliance, maximum flow rate (Qmax), PVR, voiding detrusor pressure at Qmax (PdetQmax), BOOI, BCI, and voiding efficiency (VE, defined as voided volume/bladder capacity × 100) were measured and recorded. The definition of BOO was based on the ICS definition of obstruction [Citation9].

Symptoms of men with DUA were analyzed and compared with those of men with BOO based on eight questions on erectile dysfunction, long duration of voiding, nocturia, abdomen distension, sensation of void, straining, bowel dysfunction, and weak stream (). The questions were selected from the many different clinical presentations between DUA and BOO based on a large-scale study about distinguishing symptoms of DUA [Citation5,Citation6]. One experienced urologist (A.R. Kim) reviewed clinical data including patient interviews, medical history, and bladder diary, and scored each question of the DUA-SQ on a scale from 0 to 15 without referring to the UDS. Patients with higher scores on the DUA-SQ may have DUA.

Table 1. Questionnaire for differential diagnosis between DUA and BOO.

The interclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for agreement from three responders (A.R. Kim, Y.J. Park, and K.O. Heo) were calculated for the overall total score and for the two domains to test the test–retest reliability. A score of 0.8 or higher was considered good [Citation10]. SPSS version 21 was used to perform statistical analyses. Mean ± SD were used to present descriptive results for continuous data. Differences between groups were tested with the Student’s t-test for continuous variables. p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. Predictive power was analyzed using the area under the curve (AUC) in plots of sensitivity versus 1-specificity, and the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves. The larger the AUC, the higher the predictability of the index.

Results

We identified 3164 eligible patients’ records. Strict criteria were used to avoid overlap when classifying patients with pure DUA or BOO. Men with a low BCI and a high BOOI, suggesting simultaneous DUA and BOO, were excluded from the analysis. Using these criteria, 3164 patients’ records were classified with pure DUA (n = 165) or BOO (n = 153), and included in the analysis (Supplementary Figure S1).

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are shown in . The mean age (±SD) of the DUA and BOO group were 67.0 ± 8.8 and 65.0 ± 15.1 years, respectively. Prostate size was significantly different between the groups (33.8 ± 17.6 vs. 60.6 ± 32.1 cc, p < .001). The mean ± SD of voided volume, maximum flow rate, and PVR of the DUA and BOO group were 158.6 ± 159.7 ml, 7.2 ± 5.6 m/s, 161.3 ± 183.2 ml and 211.0 ± 129.2 ml, 8.6 ± 3.6 m/s, 89.9 ± 102.7 ml, respectively, on UFM. Of these, PVR was significantly different between groups (p < .001). Mean ± SD BCI (60.4 ± 30.7 vs. 121.9 ± 32.4) and BOOI (13.0 ± 13.4 vs. 63.7 ± 34.5) were also significantly different between groups in the UDS (all p < .001). The International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), which was recorded by patients, was compared between the groups. Voiding and storage subscores, and total scores were not significantly different between groups ().

Table 2. Patients’ characteristics in DUA and BOO.

Comparison of scores in the DUA-SQ between DUA and BOO

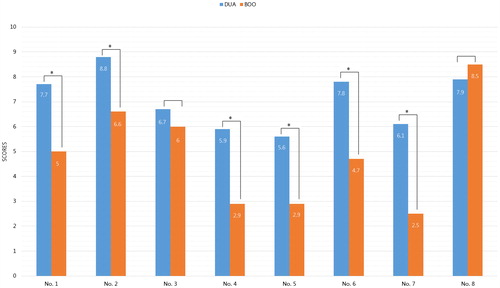

The mean variable of question number from 1 to 8 was 7.7 versus 5.0, 8.8 versus 6.6, 6.7 versus 6.0, 5.9 versus 2.9, 5.6 versus 2.0, 7.8 versus 4.7, 6.1 versus 2.5, and 7.9 versus 8.5 in DUA and BOO, respectively. All items in the DUA-SQ, except for questions 3 and 8, were significantly different between groups (all p < .001; ).

Sensitivity, specificity, and cutoff value assessment

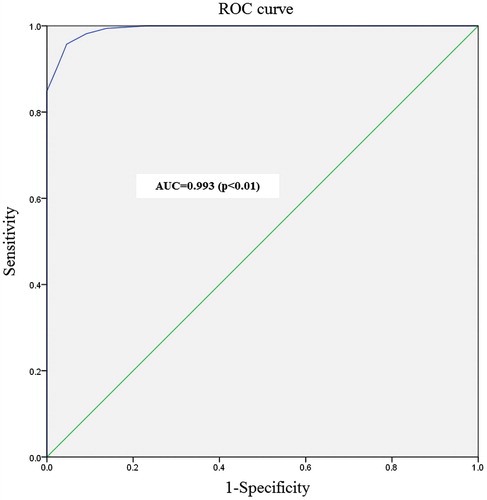

We analyzed ROC curves to evaluate DUA-SQ sensitivity and specificity. The AUC was 0.993 and asymptotic significance (p) was less than 0.05. Sensitivity and specificity of the DUA-SQ were 95.8% and 95.4%, respectively, in patients with scores greater than 45 points (cutoff value; ).

Reliability analysis

The internal consistency for the total score of the DUA-SQ was considered good with a Cronbach’s alpha less than 0.8. The ICC was 0.970 and 0.950 when total scores of DUA (74.6 vs. 73.5 vs. 64.4) and BOO (22.9 vs. 22.5 vs. 21.8) from three responders were analyzed and compared. The ICC of the total scores from the three responders of the DUA-SQ was 0.988.

Discussion

We found that this novel questionnaire helped us distinguish between men with DUA from those with BOO. Several valuable studies have previously demonstrated the possibility of diagnosing these patients without performing a UDS [Citation5–7,Citation11]. Although a few questionnaires have been used to diagnose and evaluate patients with LUTS [Citation12–14], to the best of our knowledge, no questionnaire exists that could have been used for the purpose of our study. Therefore, we developed a novel questionnaire, the DUA-SQ, for the differential diagnosis of patients with DUA, from those with BOO, which is very important and valuable.

In this study, patients with DUA and BOO showed different scores for all questions except for question 3 (nocturia) and 8 (weak stream). Nocturia is common in men with LUTS; however, it should be assessed as a distinct condition, as well as a component of systemic disease. Weak stream is also a very common symptom in men with LUTS. The other questions pertaining to erectile dysfunction, abdominal distension (palpable bladder), void sensation, straining, and bowel dysfunction (difficulty of defecation) were significantly different, and therefore may help with the differential diagnosis between the diseases. Based on its high sensitivity and specificity, we could expect that men with LUTS who have greater than 45 points on the DUA-SQ may have DUA.

Many patients with LUTS have recently visited our urology clinic; however, we should recommend UDS for the differential diagnosis of DUA and BOO, because of the completely different therapeutic strategy needed for the 2 diseases [Citation15,Citation16]. DUA seems to be a serious burden for the older population due to the lack of simple and noninvasive diagnosis tool. Noninvasive techniques assessing contraction strength have been explored but have not yet replaced standard UDS in clinical practice. An inflatable penile cuff has been developed to diagnose BOO; however, the test was limited by frequent failure and artifacts. Common problems with the technique include lack of appreciation of abdominal straining and pressure transmission capture [Citation17]. Moreover, the main cause for the lack of diagnostic tools for DUA is due to its unclear pathophysiology [Citation1]. Proposed etiologies include neurogenic, myogenic, and mixed causes. The neurogenic hypothesis suggests that DUA results from the damage of peripheral innervations of the lower urinary tract. Several studies reported that patients with problems in peripheral innervations of the lower urinary tract showed erectile dysfunction [Citation18,Citation19]. The myogenic hypothesis suggests a direct defect of the bladder muscle leading to diminished cell excitability and loss of intrinsic contractility of the muscle cells of the bladder. In the last hypothesis, the two hypotheses are combined [Citation20–22]. However, pathophysiology remains a controversial issue. The DUA is innervated by the autonomic and somatic nervous system, and its central control is highly complex. Injury to pelvic nerves induces efferent and afferent dysfunction of the urinary tract system. In addition, DUA is found in more than 80% of patients with diabetes mellitus [Citation23]. The etiology of diabetic bladder dysfunction is multifactorial as functional and morphological changes are found in nerves and muscles of the bladder. Several researches supported that erectile dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, and LUTSs [Citation24,Citation25]. DUA is more prevalent in the elderly, and has been reported in approximately 30% of men aged greater than 50 years, and 50% of men aged greater than 70 years [Citation1,Citation26]. The incidence of diabetes mellitus in the two groups was not significantly different (48% vs. 45%); however, we did not have access to the data on the duration of diabetes mellitus or hemoglobin A1c, which may be more important than incidence. In addition, a definitive treatment tool for DUA is lacking due to the lack of a clear pathophysiology for DUA, because treatment strategy should be developed based on the pathophysiology. Several strategies, including stem cell therapy and neuro-modulation have been proposed; however, long-term research and clinical trial are needed to demonstrate its clinical efficacy [Citation15].

One limitation of the developing questionnaire is that it was tested using retrospective data; therefore, large-scale prospective studies should be conducted to confirm our results. In addition, it was hard to detect patients who overlap with DUA and BOO using the questionnaire, because it was designed for the differential diagnosis of these diseases. Although our results indicated a high sensitivity and specificity for the questionnaire, UDS are indispensable for the prospective evaluation of symptoms and a precise diagnosis of patients with DUA. However, our results demonstrate that the questionnaire, which has the advantage of being simple, may be beneficial for a quick assessment and differential diagnosis of patients with DUA from those with BOO.

Conclusions

This novel, simple, and noninvasive questionnaire may be a useful tool for the differential diagnosis of patients with DUA, from those with BOO in the outpatient clinic. Large-scale clinical trials are needed to further validate the sensitivity and specificity of this novel questionnaire.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval is obtained from Konkuk University Medical Center: KUH1130057.

Supple_fig_1.tif

Download TIFF Image (51.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Osman NI, Chapple CR, Abrams P. Detrusor underactivity and the underactive bladder: a new clinical entity? A review of current terminology, definitions, epidemiology, aetiology, and diagnosis. Eur Urol. 2014;65:389–398.

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn. 2002;21:167–178.

- Andersson KE. Detrusor underactivity/underactive bladder: new research initiatives needed. J Urol. 2010;184:1829–1830.

- Dewulf K, Abraham N, Lamb LE, et al. Addressing challenges in underactive bladder: recommendations and insights from the Congress on Underactive Bladder (CURE-UAB). Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49:777–785.

- Gammie A, Kaper M, Dorrepaal C, et al. Signs and symptoms of detrusor underactivity: an analysis of clinical presentation and urodynamic tests from a large group of patients undergoing pressure flow studies. Eur Urol. 2016;69:361–369.

- Aldamanhori R, Chapple CR. Underactive bladder, detrusor underactivity, definition, symptoms, epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, and risk factors. Curr Opin Urol. 2017;27:293–299.

- Rademakers KL, van Koeveringe GA, Oelke M. Detrusor underactivity in men with lower urinary tract symptoms/benign prostatic obstruction: characterization and potential impact on indications for surgical treatment of the prostate. Curr Opin Urol. 2016;26:3–10.

- Jeong SJ, Kim HJ, Lee YJ, et al. Prevalence and clinical features of detrusor underactivity among elderly with lower urinary tract symptoms: a comparison between men and women. Korean J Urol. 2012;53:342–348.

- Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology of lower urinary tract function: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:116–126.

- Runyan CW, Schulman M, Dal Santo J, et al. Work-related hazards and workplace safety of US adolescents employed in the retail and service sectors. Pediatrics. 2007;119:526–534.

- Smith PP, Birder LA, Abrams P, et al. Detrusor underactivity and the underactive bladder: symptoms, function, cause-what do we mean? ICI-RS think tank 2014. Neurourol Urodynam. 2016;35:312–317.

- Rodrigues P, Meller A, Campagnari JC, et al. International Prostate Symptom Score-IPSS-AUA as discriminant scale in 400 male patients with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). Int Braz J Urol. 2004;30:135–141.

- Weinberg AC, Brandeis GH, Bruyere J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Overactive Bladder Symptom Score in Spanish (OABSS-S). Neurourol Urodyn. 2012;31:664–668.

- D’Silva KA, Dahm P, Wong CL. Does this man with lower urinary tract symptoms have bladder outlet obstruction? The Rational Clinical Examination: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312:535–542.

- Chai TC, Kudze T. New therapeutic directions to treat underactive bladder. Investig Clin Urol. 2017;58:S99–S106.

- Woo MJ, Ha Y-S, Lee JN, et al. Comparison of surgical outcomes between holmium laser enucleation and transurethral resection of the prostate in patients with detrusor underactivity. Int Neurourol J. 2017;21:46–52.

- Malde S, Nambiar AK, Umbach R, et al. Systematic review of the performance of noninvasive tests in diagnosing bladder outlet obstruction in men with lower urinary tract symptoms. Eur Urol. 2017;71:391–402.

- Tsai C-C, Liu C-C, Huang S-P, et al. The impact of irritative lower urinary tract symptoms on erectile dysfunction in aging Taiwanese males. Aging Male. 2010;13:179–183.

- Nakamura M, Fujimura T, Nagata M, et al. Association between lower urinary tract symptoms and sexual dysfunction assessed using the core lower urinary tract symptom score and international index of erectile function-5 questionnaires. Aging Male. 2012;15:111–114.

- Osman NI, Chapple CR. Contemporary concepts in the aetiopathogenesis of detrusor underactivity. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:639–648.

- Drake MJ, Williams J, Bijos DA. Voiding dysfunction due to detrusor underactivity: an overview. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:454–464.

- Aizawa N, Igawa Y. Pathophysiology of the underactive bladder. Investig Clin Urol. 2017;58:S82–S89.

- Daneshgari F, Liu G, Birder L, et al. Diabetic bladder dysfunction: current translational knowledge. J Urol. 2009;182:S18–S26.

- Aktas BK, Gokkaya CS, Bulut S, et al. Impact of metabolic syndrome on erectile dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms in benign prostatic hyperplasia patients. Aging Male. 2011;14:48–52.

- Demir O, Akgul K, Akar Z, et al. Association between severity of lower urinary tract symptoms, erectile dysfunction and metabolic syndrome. Aging Male. 2009;12:29–34.

- Kaya E, Sikka SC, Kadowitz PJ, et al. Aging and sexual health: getting to the problem. Aging Male. 2017;20:65–80.