Abstract

The aim of this study was to evaluate the relationship between quality of life, erectile function and group psychotherapy in patients with prostate cancer undergoing radical prostatectomy. Sixty patients were evaluated for erectile function (IIEF-5), quality of life (SF-36SF), urinary incontinence (ICQI-SF and ICQI-OAB). Thirty of them had group psychotherapy two weeks before and 12 weeks after surgery. Patients who underwent group psychotherapy had better scores in IIEF-5, satisfaction with life in general, satisfaction with sexual life and in partner relationship; better results of SF-36SF, excepting two domains: bodily pain and role emotional. There were significant correlations between IIEF-5 and perception of discomfort (p = .030), physical functioning (p = .021), physical component (p = .005) and role emotional (p = .009) in patients undergoing group psychotherapy. In patients who didn't have group psychotherapy there were significant correlations between ICQI-OAB and perception of discomfort (p = .025), social functioning (p = .052) and role emotional (p = .034); between ICQI-SF and perception of discomfort (p = .0001). Group psychotherapy has a positive impact in quality of life and erectile function. There was no difference in the urinary function of the two groups. Further studies are necessary to identify the impact of self-perception and self-knowledge in the postoperative management of radical prostatectomy.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common malignancy in elderly men and a major public health problem. Age is a relevant risk factor, with a proven histological PCa being found in 60% of men by the age of 70 years and 80% by the age of 80. It remains the most common solid tumor in men and is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States, as in Brazil [Citation1]. The frequency of PCa is growing not only in western cultures, but also its incidence is dramatically increasing in eastern nations. In fact, PCa is considered a chronic disease, needing a long period for initiation, development, and progression [Citation2].

The progressive ageing of the world male population will further increase the need for tailored assessment and treatment of PCa patients.

In particular, sexual health, urinary continence, and bowel function can be worsened after prostatectomy, radiotherapy, or hormone treatment, mostly in elderly population [Citation3].

Men with clinically localized PCa who chooses for surgery can expect excellent long-term survival for 10-year disease specific survival, around 94% [Citation4].

The primary goal of any definitive treatment of PCa is the improvement of survival and QoL: although surgery, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy can lead to long-term survival, these treatments can cause lasting side effects. Therefore, patients’ survival has to be considered in treatment decision-making, but patients’ quality of life must also be considered before and after any treatment [Citation5].

Radical prostatectomy (RP) is a curative treatment for early prostate cancer, with a proven long-term survival benefit [Citation6]. Optimal outcomes of RP are not limited to cancer control, but also include urinary continence and preservation of erectile function (EF). Preservation of EF has become a goal in prostate cancer surgery with advances in our understanding of the prostate and cavernous nerve anatomy and with the introduction of nerve-sparing RP by Walsh and Donker [Citation7].

The recovery of urinary continence after RP is an important aspect to preserve general health and to maximize the outcomes of sexual rehabilitation. After catheter removal, most patients reported some level of urinary incontinence [Citation8]. The incidence of post prostatectomy urinary incontinence ranges from 0% to 87% [Citation9,Citation10].

The frequency of urinary incontinence varies depending on the type of surgery and surgical technique, but it tends to improve from one to two years later [Citation11]. However, some patients remain with urinary incontinence. It was observed, by the urodynamic study, high frequencies (87%) of incontinence in patients after RP [Citation12].

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a critical point related to QoL in men treated for PCa and it is strongly associated with depression and significant distress [Citation13]. ED is associated with depressive symptoms even though patients were approximately four years post diagnosis. These data suggest ED in men with prostate cancer can have lasting psychological effects [Citation14]. ED has a negative effect on the quality of life of men and their sexual partners, and not uncommonly, the burden of ED persists long after cancer cure concerns have subsided [Citation15]. The reported incidence of long-term ED after RP ranges from approximately 14–90%, a too wide a range to permit proper patient counseling and treatment selection decision-making [Citation9].

Also, ED is often associated with other age-related comorbidities. The aging process affects the structural organization and function of penile erectile components such as smooth muscle cell and vascular architecture. These modifications affect penile hemodynamics by impairing cavernosal smooth muscle cell relaxation, reducing penile elasticity, compliance and promoting fibrosis [Citation16].

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is based on the World Health Organization's definition of health as not merely the absence of disease or infirmity, but as a state of physical, emotional, and social well-being [Citation17].

The identification of the physical and psychological consequences of the disease and its various treatments is a very important issue that has to be considered [Citation5].

Group therapy is a widely practiced mode of treatment employed in a vast number of settings, with a proven degree of effectiveness. An educational-behavioral group for patients with the same issue, prostate cancer and RP, is usually designed to meet for 12 sessions [Citation18].

Patients and methods

A local ethics committee approved the study. Were selected 60 patients who underwent RP as a treatment for PCa 10 years ago, and 30 of them had group psychotherapy. The same psychologist administered group psychotherapy in weekly sessions, with two meetings before RP and 12 after.

They were evaluated by an independent valuer using a questionnaire, consisted with aspects of satisfaction with the partner, the intimacy with the partner, satisfaction with sex life and with life in general, by scores from one to five, being the higher score corresponded to better satisfaction. The questionnaire – QAPSSCaP-Naccarato, was developed by the researcher and is under process of validation [Citation19].

The evaluation of QoL was performed using the Short-Form Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36), and the evaluation of erectile function through the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5).

The SF-36 is a generic multidimensional assessment instrument consisting of 36 items, comprising eight scales: physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health perceptions, energy/vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health with a final score 0–100 in which zero represents the worst and 100 the best state [Citation20].

The IIEF-5 is a useful subjective tool for grading ED, containing five questions in each five-point scale (1–5) with a total score range of 1–25, indicating ED characterized by a score <21. ED is classified into four categories: severe (1–7); moderate (8–11); mild to moderate (12–16); mild (17–21) and normal erectile function (22–25) [Citation21].

During the evaluation all patients answered the questionnaires “International Consultation on Incontinence-Short Form” (ICIQ-Short-Form) [Citation22] to assess the presence of incontinence, and “International Consultation on Incontinence-OAB” (ICIQ-OAB) to assess symptoms of overactive bladder with analog scale from zero to ten to quantify the impact of each symptom on quality of life [Citation23].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis with presentation of frequency tables measures for categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test or Chi-square test was used to compare ratios of continuous and sequential measurements between the two groups.

The significance level for statistical tests was 5% and the software utilized was SAS System for Windows (Statistical Analysis System), version 9.2.

Results

The mean age was 70 years, and there were no differences between the groups related to Gleason score, Diabetes, Hypertension, radiotherapy and chemotherapy, except for the patients who used sexual medication (.

Table 1. Demographic data and differences between patients who underwent psychotherapy and no psychotherapy.

Among the 60 patients 68% accepted the disease and 32% reported concern, with no difference between groups.

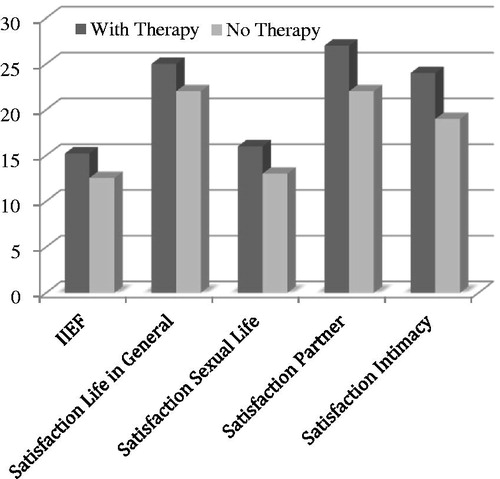

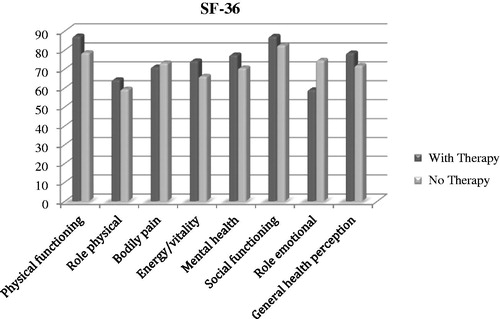

The 30 patients who underwent group psychotherapy had no significant statistical difference in the results ; but showed better scores in IIEF-5, in satisfaction with life in general, satisfaction with sexual life, satisfaction in the partner relationship ; and better results of SF-36, excepting two domains: bodily pain and role emotional .

Figure 1. Patients satisfaction in IIEF-5, with life in general, sexual life, partner and intimacy, with better results in patients who underwent psychotherapy.

Figure 2. SF-36 better results in patients who underwent psychotherapy, excepting two domains: bodily pain and role emotional.

Table 2. Statistical differences between groups.

There were significant correlations between IIEF-5 and perception of discomfort (p = .030), physical functioning (p = .021), role Physical (p = .005) and role Emotional (p = .009) (.

Table 3. Multivariate analysis correlating the questionnaires with the different domains from patients who underwent group psychotherapy.

This group showed significant difference related to use of inhibitor of phospodiesterase-5, just after surgery (p = .0019). But after 10 years of the procedure there is no difference between the groups.

In patients who did not undergo group psychotherapy there were significant correlations between ICIQ-OAB and perception of discomfort (p = .025), social functioning (p = .052) and role emotional (p = .034); between ICIQ-SF and perception of discomfort (p = .0001); between perception of discomfort and general health perception (0.051), role emotional (0.032) and mental health (0.046) (.

Table 4. Multivariate analysis correlating the questionnaires with the different domains from patients who did not underwent group psychotherapy.

There was significant difference, with worse score, in ICIQ-SF among the patients who had radiotherapy (p = .001).

Discussion

Many men undergoing RP will experience significant short-term urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction that both may impair their general QoL [Citation14].

ED is a major concern of men undergoing RP. As many as 45–64% of RP candidates suffer from ED preoperatively [Citation24]. The treatment-related incidence of ED is far more common than incontinence at all follow-up intervals. Therefore, ED will impact a large proportion of men temporarily and permanently [Citation25].

Development in the management of PCa and improved longevity after curative treatment for clinically localized disease has placed increase attention on patient psychological aspects after treatment, particularly those related to sexual function [Citation19].

The expression “quality of life”, more specifically “health related quality of life”, refers to physical, psychological, and social realms, seen as individual and distinct areas, which are influenced by beliefs, attitudes, values, and an individual’s perception of health [Citation17].

With the established effectiveness of diverse treatments for localized prostate cancer, the identification of the physical and psychological consequences of the disease and its various treatments has become an important issue. We are forced to evaluate the patient’s physical, psychological, and social aspects prior and after treatment.

Sexuality is often neglected by being mystified as an expected problem in older men, or when, after surgery, has the main focus (cancer) treated, ceases to recognize the importance of sexual function for overall health of this population. Staying sexually and socially active is associated with physical and mental health [Citation26].

We understand that today the existing knowledge of survival data, complication rates and responses to treatments for the symptoms is not enough, so that we can assess the impact of the disease and its treatment. We must evaluate the quality of life of patients – as it was before and how it is after treatment, taking into account physical, psychological and social aspects.

Men with sexual dysfunction are less likely to perceive the quality of their overall relationship as relevant to their sexual problems. Self-esteem and social success appear to play a sexually satisfying effect, possibly more in men than in women. Unfortunately, the team of care does often not identify the sexual difficulties and most patients receive little or no assistance to deal with the effects of the disease and deal with the intimacy with the partner.

Erectile function recovery rates after radical prostatectomy varies greatly based on a number of factors, such as differences in erectile dysfunction definition, data acquisition means, time-point post-surgery, and population studied. However, it is of concern that most of the studies did not focus on the couple for the interventions and evaluations.

While the benefit of patient’s partner assessment is to be better explored due to the scarcity of this methodological scope, psychotherapy was shown to improve results in this scenario [Citation19].

In particular, ED is a critical point related to Qol in men treated for PCa and it is strongly associated with depression and significant distress [Citation14].

Men with more impairment of physical and mental health are less likely to achieve successful sexual rehabilitation after treatment or because distress about sexual dysfunction has a negative influence on men’s perceptions of their current mental and physical health. The factors beyond the effects of age, health, and treatment that are related strongly to sexual satisfaction at long-term follow-up are more cognitive and behavioral: having one or more current partners who are functional sexually, having had good sexual function before treatment, and putting a high priority on preserving sexual function in choosing a treatment. These are factors that may be targeted by sexual counseling interventions that would complement and enhance efforts at medical treatment for men with ED [Citation27].

Men’s masculine identity is affected by the experience of having PCa and, in particular, by the consequences of surgical treatment. The loss of erectile function as a consequence of side effects of treatment of PCa clearly has a significant impact on men’s masculinity identity. Stereotypically masculine qualities of emotional control and rationality were drawn on in describing their reaction to the diagnosis and treatment of cancer but they also experienced a new found sense of physical vulnerability. Gannon and colleagues pointed that one way of addressing these issues is to focus on the language used in speaking about health, illness and gender [Citation28].

One study compared the impact of radiotherapy and RP on urinary and intestinal symptoms and found a higher incidence of urinary incontinence in patients who underwent RP and more intestinal symptoms in patients who underwent radiotherapy (RT) [Citation29].

Morgia and colleagues pointed that patients should be addressed about the occurrence of long term ED after brachytherapy for PCa, and those kind of patients could be approached with penile rehabilitation at the early phase [Citation30].

Potosky and colleagues measured quality of life in 1187 patients who had surgery or radiotherapy and reported higher incidence of urinary problems in the surgery group and higher incidence of bowel problems in the radiotherapy group [Citation31].

In a prospective study of 3533 patients given surgery or radiotherapy, Resnick and colleagues showed similar patterns in urinary, sexual, and bowel function, but they did not report on specific complications or their associated treatments [Citation32]. Nam et al. [Citation33] describe that men treated with radiation after radical prostatectomy had a higher rate of incontinence surgery than men without radiation. Physiological reasons to explain this could be radiation cystitis effects causing detrusor over activity and bladder neck.

In the present study, after 10 years of treatment, a significant difference was observed in the urinary symptoms of patients who underwent RT after RP compared to those who did only RP. Patients who did only RP had a decline in urinary symptoms after the passage of the years, as reported in the literature.

Another aspect be presented is the hormonal profile (testosterone) in this group of patients. There is small studies recently conducted that suggested that T therapy can be given to men following RP without increasing the risk of disease recurrence or progression [Citation34–36].

Buvat et al. [Citation37] has questioned the association between low T and ED and the beneficial effect of T therapy on ED in particular. Young men with Testosterone Deficiency (TD) seen to present more benefits with T therapy than the aging men.

The state-of-art medical practice following PCa surgery involves the concept of penile rehabilitation. But the negative emotional and relationship difficulties impact the patients and the partner. A combined approach, where medical treatments and psychosocial interventions are used together, is the way to improve Qol for these patients [Citation38].

AUA guideline states that patients with TD and a history of CaP should be informed there is inadequate evidence to quantify the risk-benefit ratio of T therapy. This was an expert opinion statement, given the limited nature of available literature.

The recommendations from the Fourth International Consultation for Sexual Medicine about T therapy, with low level of evidence and degree of recommendation, depending on the type of cancer treatment, if there is no evidence of residual cancer, and after a prudent interval [Citation39].

There are similarities in treating testosterone deficiency in different countries in different parts of the world about the fear that the physicians or the patients themselves have about potentially carcinogenic effects of the testosterone on the prostate [Citation40]. But, sexual, metabolic and psychological changes developed with age in males are not directly associated with testosterone levels [Citation41].

Definitive conclusions regarding the safety of T therapy in men with a history of PCa must wait for more studies, with a larger trial. More clinical trials are needed to determine its efficacy in aiding in erectile function recovery.

There is consistent evidence that endothelial damage is intimately linked to ED, and this manifestation seems to be associated with appearance cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). On the other hand, physical activity has been pointed out as an important clinical strategy in the prevention and treatment of CVDs and ED mainly associated with improvement of endothelial function, and should be considered in the post treatment for PCa [Citation42].

Little research has been done in the area of psychosocial interventions in penile rehabilitation, and there are no guidelines for specific recommendations or consensus regarding the optimal rehabilitation protocol or treatment. Future studies with multidisciplinary approaches should define the role of specific psychosocial interventions tailored to the individual personality, and include evaluation of the influence of the partner.

The treatments are continuing to develop, providing improvement on the long-term results for patients and partners, especially the side effects. With these advances we will be able to offer cancer survivors a better Qol.

An important aspect is the educational and informative part of the disease, where we clarify doubts and undo myths, making room for expression and affective contact. The identification of the patient’s own needs, managing themselves in search of a better quality of life within their own limitations, and mostly, their potential to become an information tool in the social group to which they belong, are fundamental and emphasized at every meeting [Citation43].

Considering the integrated approach, where the psychological and sexual therapies have the same importance, we must understand, assist and guide patients, their partners and their family.

Conclusions

Group psychotherapy has a positive impact on the Qol of patients and the erectile function. There was no difference in the urinary function of the two groups, only worsening of the symptoms when compared to the patients who had associated radiotherapy. Further studies are necessary to identify the impact of self-perception and self-knowledge in the postoperative management of RP.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Instituto Nacional do Câncer (INCA). 2016 [cited 2016 Feb 12]. Available from: https://www2.inca.gov.br

- Kyrdalen AE, Dahl AA, Hernes E, et al. A national study of adverse effects and global quality of life among candidates for curative treatment for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2013;111:221–232.

- Köhler N, Friedrich M, Gansera L, et al. Psychological distress and adjustment to disease on patients before and after radical prostatectomy. Results of a prospective multi-centre study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2014;23:795–802.

- Lu-Yao GL, Yao SL. Population-based study of long-term survival in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer. Lancet 1997;349:906–910.

- Namiki S, Arai Y. Health-related quality of life in men with localized prostate cancer. Int J Urol. 2010;17:125–138.

- Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Ruutu M, et al. Radical prostatectomy versus watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1977–1984.

- Walsh PC, Donker PJ. Impotence following radical prostatectomy: insight into etiology and prevention. J Urol. 1982;128:492–497.

- Bianco FJ, Jr., Scardino PT, Eastham JA. Radical prostatectomy: long-term cancer control and recovery of sexual and urinary function (“trifecta”). Urology 2005;66:83–94.

- Alivizatos G, Skolarikos A. Incontinence and erectile dysfunction following radical prostatectomy: a review. Sci World J. 2005;5:747–758.

- Nandipati KC, Raina R, Agarwal A, et al. Erectile dysfunction following radical retropubic prostatectomy: epidemiology, pathophysiology and pharmacological management. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:101–117.

- Hunskaar S, Burgio K, Diokno AC, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of urinary incontinence. In: Abrams P, Cardozo L, Khoury S, Wein A, editors. Incontinence: 2nd International Consultation on Incontinence. Plymouth (UK): Health Publications; 2002. p. 165–200.

- Rudy DC, Woodside JR, Crawford ED. Urodynamic evaluation of incontinence in patients undergoing modified Campbell radical retropubic prostatectomy: a prospective study. J Urol. 1984;132:708–712.

- Eton DT, Lepore SJ. Prostate Cancer and health-related quality of life: a review of the literature. Psychooncology 2002;11:307–326.

- Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Roth AJ. The association between erectile dysfunction and depressive symptoms in men treated for prostate cancer. J Sex Med. 2011;8:560–566.

- Schover LR, Fouladi RT, Warneke CL, et al. Defining sexual outcomes after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer 2002;95:1773–1785.

- Kaya E, Sikka SC, Kadowitz PJ, et al. Aging and sexual health: getting to the problem. Aging Male. 2017;20:65–80.

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2016. Available from: www.who.int

- Vinogravov S, Yalom ID. Group Psychotherapy American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1989.

- Naccarato AM, Reis LO, Zani EL, et al. Psychotherapy: a missing piece in the puzzle of post radical prostatectomy erectile dysfunction rehabilitation. Actas Urol Españolas. 2014;38:385–390.

- Ciconelli RM, Ferraz MB, Santos W, et al. Tradução para a língua portuguesa e validação do questionário genérico de avaliação de qualidade de vida SF – 36 (Brasil SF-36)/Brazilian-Portuguese version of the SF-36. A reliable and valid quality of life outcome measure. Rev Bras Reumatol. 1999;39:143–150.

- Gonzáles AI, Sties SW, Wittkopf PG, et al. Validation of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIFE) for use in Brazil. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2013;101:176–182.

- Tamanini JTN, Dambros M, D‘ancona CAL, et al. Responsiveness to the Portuguese version of the international consultation on incontinence questionnaire – short form (ICIQ-SF) after stress urinary incontinence surgery. Int Braz J Urol. 2005;31:482–489:discussion 490.

- Pereira SB, Thiel Rdo R, Riccetto C, et al. Validação do International Consultation on Incontinence Question-naire Overactive Bladder (ICIQ-OAB) paralíngua portuguesa. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2010;32:273–278.

- Salonia A, Zanni G, Gallina A, et al. Baseline potency in candidates for bilateral nerve-sparing radical retropubic prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2006;50:360–365.

- Prabhu V, Lee T, McClintock TR, et al. Short-, Intermediate-, and Long-term Quality of Life outcomes following radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer. Rev Urol. 2013;15:161–177.

- Naccarato AMEP, Reis LO, Ferreira U, et al. Psychotherapy and phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor in early rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Andrologia 2016;48:1183–1187.

- Penedo FJ, Molton I, Dahn JR, et al. A randomized clinical trial of group-based cognitive-behavioral stress management in localized prostate cancer: development of stress management skills improves quality of life and benefit finding. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31:261–270.

- Gannon K, Guerro-Blanco M, Patel A, et al. Re-constructing masculinity following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Aging Male. 2010;13:258–264.

- Nam RK, Cheung P, Herschorn S, et al. Incidence of complications other than urinary incontinence or erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:223–231.

- Morgia G, Castelli T, Privitera S, et al. Association between long-term erectile dysfunction and biochemical recurrence after permanent seed I(125) implant brachytherapy for prostate cancer. A longitudinal study of a single-institution. Aging Male. 2016;19:15–19.

- Potosky AL, Davis WW, Hoffman RM, et al. Five-year outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:1358–1367.

- Resnick MJ, Koyama T, Fan KH, et al. Long-term functional outcomes after treatment for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:436–445.

- Nam RK, Herschorn S, Loblaw DA, et al. Population based study of long-term rates of surgery for urinary incontinence after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2012;188:502–506.

- Rastrelli G, Corona G, Vignozzi L, et al. Serum PSA as a predictor of testosterone deficiency. J Sex Med. 2013;10:2518–2528.

- Morgentaler A, Conners WP. Testosterone therapy in men with prostate cancer: literature review, clinical experience, and recommendations. Asian J Androl. 2015;17:206–211.

- Kaufman JM, Graydon RJ. Androgen replacement after curative radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer in hypogonadal men. J Urol. 2004;172:920–922.

- Buvat J, Maggi M, Guay A, et al. Testosterone deficiency in men: systematic review and standard operating procedures for diagnosis and treatment. J Sex Med. 2013;10:245–284.

- Emanu JC, Avildsen IK, Nelson CJ. Erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: prevalence, medical treatments, and psychosocial interventions. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2016;10:102–107.

- Khera M, Adaikan G, Buvat J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of testosterone deficiency: recommendation from the fourth international consultation for sexual medicine (ICSM 2015). J Sex Med. 2016;13:1787–1804.

- Gooren LJ, Behre HM, Saad F, et al. Diagnosing and treating testosterone deficiency in different parts of the world. Results from global market research. Aging Male. 2007;10:173–181.

- Kocoglu H, Alan C, Soydan H, et al. Association between the androgen levels and erectile function, cognitive functions and hypogonadism symptoms in aging males. Aging Male. 2011;14:207–212.

- Leoni LA, Fukushima AR, Rocha LY, et al. Physical activity on endothelial and erectile dysfunction: a literature review. Aging Male. 2014;17:125–130.

- Naccarato A. Erectile dysfunction: a Reichian point of view. Psicologia Corporal. 2007;8:26–33.