Abstract

Tuberculous mastitis (TBM) is relatively rare disease with an incidence ranging between 0.1 and 4%. Most of the cases are culture negative and often mistaken with chronic benign idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM). It is very crucial to distinguish culture negative TBM from other causes of mastitis as the treatment differs tremendously. We describe here in a young woman originally from India and residing in Qatar; a non endemic area of tuberculosis; for more then fifteen years. She presented with 2 months history of right breast mass, followed by low grade fever, dry cough, headache, erythema nodosum, arthritis, and arthralgia. In view of the origin of the patient, positive family history for tuberculosis and positive quantiferon, the patient was started empirically on anti-tuberculous treatment (ATT). One week later she developed paradoxical reaction to ATT. This case illustrates unusual and rare manifestations of primary TBM and highlights the importance of differentiating and treating culture negative TBM from IGM.

Case report

A 36-year-old previously healthy Indian woman living in Qatar for fifteen years presented to general infectious disease clinic for evaluation of right breast mass and positive quantiferon. She had noticed the mass two months prior to her presentation which was gradually increasing in size. Initially, the mass was not painful and there was no skin discoloration or pus discharge. Few weeks later, the patient noticed some redness in the upper outer quadrant of her right breast, along with needle prick sensations around the mass. Subsequently, she developed persisting dry cough, occasional headache, large joint pain, and swelling were elicited. While awaiting for her investigations, she came back to the clinic after 1 week with multiple painful raised skin lesions over both legs. She was feeling feverish, maximum recorded temperature at home was 37.6 °C. She missed her period for three months and she was not pregnant. She denied any appetite or weight loss, night sweats, and any use of oral contraceptive pills. She did not have any history of breast trauma, or implant. Of note, she is a mother of three children and had breastfed all of them for an average duration of two years. She weaned her youngest child six months prior to her current illness. There was no family history of breast disease. Last traveled to India was one year prior to her presentation. Her uncle had pulmonary tuberculosis 3 years back.

Examination revealed an ill-defined mass measuring six by eight centimeter in right superior-external and medial quadrant of her right breast with mild skin erythema. The mass was firm, non-fluctuating, painless and attached to the skin and deeper tissue. There was no sinus formation or discharge and no nipple retraction. The left breast was normal and there was no associated regional lymphadenopathy. Multiple tender erythematous nodules were noticed on both legs. There was also mildly swollen left ankle with erythema and tenderness on palpation. The rest of her examination was unremarkable.

Complete blood picture showed WBC 16 × 109/L, with neutrophilia 62% hemoglobin 10.6 gm/dL, MCV 83.4, MCH 27, CRP 26 mg/L, ESR 38 mm/hr, corrected calcium 2.22 mmol/L. Rheumatoid factor <15.0 IU/mL, antinuclear anti-bodies negative, C-ANCA negative, C3 182 mg/dL, C4 50.2 mg/dL, QuantiFERON®-TB Gold positive, and vitamin D 11. Angiotensin converting enzyme was negative. HIV test was negative.

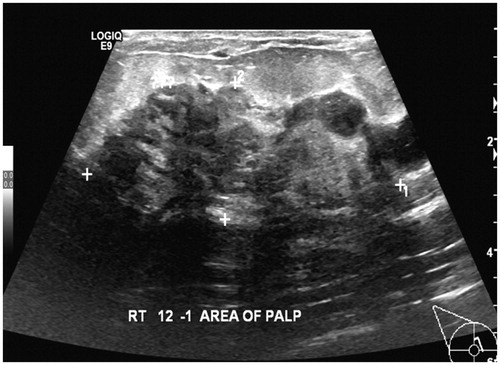

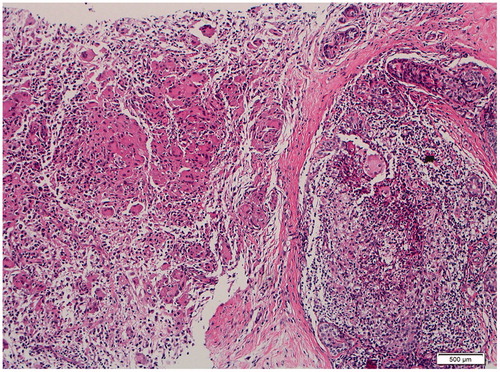

Ultrasonography (US) of the right breast showed diffuse multifocal hypoechoic branching masses occupying its upper half measuring 4.3 × 1 cm at the upper outer quadrant, 6.3 × 2.4 cm centrally located at 12 o’clock position extending to upper internal quadrant and 3.5 × 1.2 cm at 3 o’clock (). Doppler examination revealed hypervascularity with no significant axillary lymphadenopathy. XR and computed tomography (CT) of the chest showed normal lung fields with no mediastinal lymphadenopathy. CT head was reported as normal. An ultrasound guided true-cut biopsy was performed and five pieces from different sites of the mass were taken. The histopathology showed extensive non-caseating granulomatous mastitis mostly centered around terminal ducts and lobular units. Some granulomatous foci were associated with a moderate neutrophilic infiltrate (). No fungal or mycobacterium organisms were identified on special strains; Grocott methenamine silver, Ziehl-Neelsen stain and fluorescence. Breast tissue for acid fast bacilli smear, TB PCR, and TB culture were negative.

Figure 1. US right breast revealing diffuse multifocal hypoechoic branching masses occupying its upper half measuring 4.3 × 1 cm at the upper outer quadrant, 6.3 × 2.4 cm centrally located at 12 o’clock position extending to upper internal quadrant and 3.5 × 1.2 cm at 3 o’clock.

Figure 2. Extensive non-caseating granulomatous mastitis mostly centered around terminal ducts and lobular units. Some granulomatous foci are associated with moderate neutrophilic infiltrate.

Given the histopathology findings, idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is the most likely diagnosis and steroids will be the treatment of choice of such pathology. The above picture can be confused with TB mastitis and steroids will cause flare up of TB. Therefore, after a thorough discussion with multidisciplinary team and patient, we decided to start empirically ATT (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) with close follow up. After 1 week of anti-TB medication the right breast became more red, very painful with multiple superficial abscess formation (). The abscesses ruptured spontaneously and pus was sent for regular culture, TB PCR, AFB, and TB culture which came negative. Repeated US of the breast didn’t show any deep abscesses. Her cough, headache, joint pain, and erythema nodosum lesions had completely resolved within two weeks of treatment. A repeat WBC came down from 16 to 13 109/L, ESR 28 mm/hr, and CRP 24 mg/L. The acute breast changes improved on one week course of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). We continued the ATT for total 6 months. The breast mass had completely resolved at the end of treatment. On futher follow up, she came back after 1 month of stopping her ATT with a new sinus discharge from the same breast. We repeated TB culture, it came negative. Repeated breast US did not reveal any mass. We decided to extend the ATT to six more months. The sinus healed and the patient was left with scarring of the right breast (). She was completely asymptomatic one year after stopping the ATT.

Discussion

Granulomatous mastitis is an uncommon benign inflammatory disease that has been well described in literature. It is a serious problem as it can be complicated by disfiguration of the breast, and sometimes even unnecessary radical mastectomy causing serious psychological illness for females. It can be idiopathic or due to other causes such as infections like tuberculosis, bacterial, fungal, or noninfectious like malignancy, sarcodoisis, Wegner granulomatosis, foreign body, and breast implants. Most of these etiologies can be excluded comfortably after proper history and investigations. So far, no reports in literature can differentiate clearly between IGM and TBM. This might be explained by the rarety of both pathologies and absence of randomized clinical trials and poor definition. For instance, the incidence of TBM is less than 1% in all disease of the breast in industrialized countries and goes up to 4% in endemic areas of TB [Citation1–3]. The incidence in Arabian Peninsula is around 0.5% [Citation4]. Thirteen cases of confirmed TB mastitis has been reported from Qatar between 1988 and 1998 [Citation5]. The clinical presentation for TBM and IGM is very similar. Both are seen in women of childbearing age, usually following lactation, or use of oral contraceptive pills [Citation6]. Majority of cases are unilateral and involve the central or upper outer quadrant of the breast [Citation6]. They can be associated with regional lymphadenopathy (15% in IGM and 50 to 75% in TBM) pain, abscess, and sinus formation [Citation7,Citation8]. Systemic symptoms are seen more with TBM [Citation6]. However, few case reports of IGM were associated with erythema nodosum, cough, and arthritis [Citation9–11]. Few studies tried to put some clinical and histopathological criteria to help differentiating between TBM and IGM [Citation6]. For instance, Tewari et al, concluded that the most reliable criteria in differentiating IGM from TB mastitis is the histopathology which later on has been emphasized in a histopathology study by Timothy et al. [Citation12–14]. They concluded that IGM has predominantly lobular granuloma with absence of caseous necrosis, compared to tuberculous mastitis which usually centers around ducts rather than tubules. In our case, the granulomas were diffuse noncaseating and mainly invading terminal ducts and lobular units which favor IGM as per former literature reports. Despite that we were more in favor of TB mastitis as the patient was originally coming from high endemic area of tuberculosis, possible exposure to TB and had positive Quantiferon. In view of her paradoxical reaction to antituberculous medication, and improvement of her systemic symptoms, our patient most likely had TB mastitis. This case should alert the physician to always keep high suspicion of TB for patients coming from endemic area with positive Quantiferon or PPD even if all the rest of TB work up is negative. Therefore most reports advise to start first anti-TB medication in IGM before starting steroids [Citation13]. This was emphasized further in a retrospective study done by Nanyan Rao where ATT was given to 39 patient with IGM after TBM had been excluded. Patients had excellent response and achieved high cure rate with ATT [Citation13].

To our knowledge, this is the first case of primary TB mastitis associated with headaches, erythema nodosum, reactive cough and arthritis, to develop a paradoxical reaction to anti-tuberculous treatment.

Conclusion

In conclusion, IGM and culture negative TBM are great mimickers and diagnosis is usually challenging. Differentiation between them is paramount because of the implications of corticosteroid therapy in patient with tuberculosis. Increased awareness among physicians will improve understanding and management of these mimickers.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Dr. Muna Al-Maslamani for her continuous support during the preparation of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Harris SH, Khan MA, Khan R, et al. Mammary tuberculosis: analysis of thirty-eight patients. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:234–237.

- Tse GM, Poon CS, Ramachandra K, et al. Granulomatous mastitis: a clinicopathological review of 26 cases. Pathology 2004;36:254–257.

- Kakkar S, Kapila K, Singh MK, et al. Tuberculosis of the breast: a cytomorphologic study. Ada Cytol. 2000;44:292–296.

- Oh KK, Kim JH, Kook SH. Imaging of tuberculous disease involving breast. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:1475–1480.

- Al-Marri MRHA, Almosleh A, Almoslmani Y. Primary tuberculosis of the breast in Qatar: ten year experience and review of the literature. Eur J Surg. 2000;166:687–690.

- Baharoon S. Tuberculosis of the breast. Ann Thorac Med. 2008;3:110–114.

- Bakaris S, Yuksel M, Cιragil P, et al. Granulomatous mastitis including breast tuberculosis and idiopathic lobular granulomatous mastitis. Can J Surg. 2006;49:427–430.

- Gupta PP, Gupta KB, Yadav RK, et al. Tuberculous mastitis: a review of seven consecutive cases. Ind J Tubercul. 2003;50:47–50.

- Binesh F, Shiryazdi M, Bagher Owlia M, et al. Idiopathic granulomatous mastitis, erythema nodosum and bilateral ankle arthritis in an Iranian woman. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-007636

- Bes C, Soy M, Vardi S, et al. Erythema nodosum associated with granulomatous mastitis: report of two cases. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1523–1525.

- Zabetian S, Friedman BJ, McHargue C. A case of idiopathic granulomatous mastitis associated with erythema nodosum, arthritis, and reactive cough. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2.2:125–127.

- Tewari M, Shukla HS. Breast tuberculosis: diagnosis, clinical features & management. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:103–110.

- De Sousa R, Patil R. Breast tuberculosis or granulomatous mastitis: a diagnostic dilemma. Ann Trop Med Public Health. 2011;4:122–125.

- Timothy M, Paula S, Sandra J. A review of inflammatory process of the breast with a focus on diagnosis in core biopsy samples. J Pathol Transl Med. 2015;49:279–287.