Abstract

Aim

In this study, we administered a questionnaire to consecutive prostate cancer patients who received androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) for understanding the prevalence of depression symptoms.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively identified patients with prostate adenocarcinoma who received ADT between January 2015 and February 2018 at Mackay Memorial Hospital. The patients were then asked to complete the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) during an interview. The patients were divided into two groups according to PHQ-9 score: those with depression symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 6, depression group), and those without depression symptoms (PHQ-9 < 6, non-depression group). Two groups were compared using t-tests and correlation coefficients, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

There were no significant correlations between PHQ-9 scores and any of the parameters in the patients overall. In subgroup analysis, a positive correlation was found between the duration of ADT and PHQ-9 score in the patients with depression symptoms (p = .03). In addition, univariate analysis showed a positive association between the duration of ADT and PHQ-9 score, and a longer duration of ADT was further independently associated with increased PHQ-9 score in multivariate analysis in the patients with depression symptoms.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that in patients with prostate cancer and depression symptoms, the severity of the depression symptoms was positively correlated with the duration of ADT. In contrast, this association was not found in patients without depression symptoms.

Background

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common non-skin malignancy in men, and more than 80% of patients are 65 years or older at the time of the diagnosis. The diagnosis of cancer can evoke significant stress and have a negative impact on the patients. Pirl et al. reported that 10–25% of patients diagnosed with cancer have depression [Citation1], and Roth et al reported a prevalence rate of depression of 15.2% in men diagnosed with PCa [Citation2]. Therefore, it is important to understand the prevalence of depression in patients with PCa.

Patients with PCa and a high risk of progression or metastasis may receive androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) as suggested in the 2018 edition of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. Common adverse effects of ADT include hot flashes, fatigue, loss of libido, anemia, decreased muscle mass, and osteoporosis. Increasing evidence suggests that ADT may increase the risk of depression and cognitive dysfunction, and many patients with PCa who are receiving ADT have been reported to have a depressed mood. Research based on the Taiwan Longitudinal Health Insurance Database 2005 showed epidemiological evidence of an association between ADT and a subsequent diagnosis of depression disorder [Citation3]. Due to the impact on the patients’ quality of life and morbidity, it is important to elucidate the association between patients with PCa receiving ADT and depression. Therefore, in this study, we administered a questionnaire to consecutive patients with PCa who received ADT therapy to better understand the prevalence of depression symptoms.

Materials and methods

We retrospectively identified patients with prostate adenocarcinoma who received just one of ADT (leuprolide acetate, goserelin acetate or degarelix acetate) between January 2015 and February 2018 at Mackay Memorial Hospital. The inclusion criteria were pathological proof of prostate adenocarcinoma and receiving regular monthly ADT formulation over 2 months or regular 3-month of ADT formulation over 3 months. The exclusion criteria were patients who did not complete ADT therapy, previous neuropsychiatric disorders, having previously undergone radical prostatectomy or orchiectomy, with other malignancies, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG status) >1, and PCa with advanced progression. We reviewed the medical records for initial prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level, Gleason score and tumor stage. The patients were then asked to complete the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) during an interview and when surveying laboratory data (hemoglobin, PSA and testosterone), and then again at the urology clinics.

The PHQ-9 is a rapid and reliable screening tool used to diagnose depression. It consists of nine items which evaluate the DSM-IV criteria of major depression disorder in the past two weeks [Citation4,Citation5]. Each item is scored using a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day). The scores of each item are then summed to yield the total PHQ-9 score, with higher scores indicating a higher severity of depression symptoms. We used the Chinese version of the PHQ-9, which is closely related to the English version and has been validated in Taiwan [Citation6]. According to a previous study, a PHQ-9 score ≥6 has the best sensitivity and specificity to screen for depression in elderly patients (age >60 years) in Taiwan [Citation6]. All data were compared using t-tests and correlation coefficients, as appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

The use of data and the research protocol of the study were permitted and approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital. All patients gave consent to participate in the PHQ-9 evaluation. All personal information was de-identified prior to data analysis, thus ensuring patient data confidentiality.

Results

A total of 212 men with PCa who received ADT were reviewed, of whom 83 met the inclusion criteria and 129 were excluded due to the following reasons: patients who did not complete ADT (25), lost to follow-up (23), no pathological proof at our hospital (19), castration-resistant PCa (18), double cancer (13), triple cancer (1), post-radical prostatectomy (10), post-orchiectomy (3), death (7), ECOG ≥2 (7), and receiving second-line ADT (3). Among the 83 patients, 71 completed the questionnaire and 12 patients refused to complete the questionnaire. The average age of the patients was 72.5 ± 7.9 years, and the average PHQ-9 score was 4.72 ± 5.11. Twenty-nine patients (41%) had depression (PHQ-9 score ≥6) ().

Table 1. Demographics of the patients.

The PHQ-9 results are shown in . The patients were divided into two groups according to PHQ-9 score: those with depression symptoms (PHQ-9 ≥ 6, depression group), and those without depression symptoms (PHQ-9 < 6, non-depression group) (). There were no significant differences in age, cancer stage, initial PSA level, current hemoglobin level, current PSA level, current testosterone level, ADT duration (months), and bone metastasis (yes vs. no) between the two groups (p > .05).

Table 2. PHQ9 score distribution.

Table 3. Comparison between patients with and without depression symptoms.

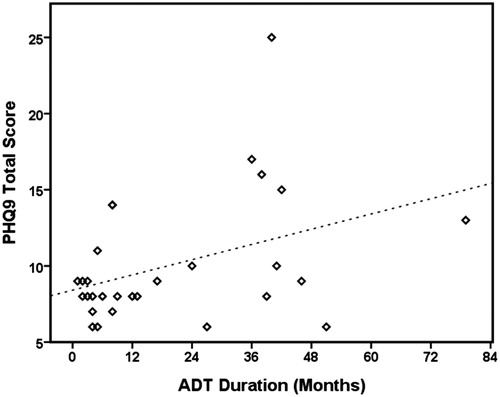

There were no significant correlations between PHQ-9 scores and any of the parameters in the patients overall (). In subgroup analysis, a positive correlation was found between the duration of ADT and PHQ-9 score in the patients with depression (p = .03). In addition, univariate analysis showed a positive association between the duration of ADT and PHQ-9 score, and a longer duration of ADT was further independently associated with increased PHQ-9 score in multivariate analysis in the patients with depression symptoms (, Figure 1).

Table 4. PHQ-9 correlation in all patients.

Table 5. Association between duration of ADT and PHQ-9 scores in uni- and multivariate models for all patients.

Discussion

Research involving self-reported depression questionnaires is important to help clinicians understand the possible adverse events of ADT on quality of life. We examined correlations of depressive symptoms in Taiwanese patients with PCa receiving ADT using the Chinese version of the PHQ-9. A cutoff point of 10 in the PHQ-9 is used for screening of depression worldwide for the general population [Citation4,Citation5]. However, this may not apply to the elderly. According to a previous study conducted to validate the Chinese version of the PHQ-9 in the elderly in Taiwan, a cutoff point of 6 to screen for depression had a higher sensitivity and specificity [Citation6]. Another study in Korea also reported that a lower cutoff point of 5 could be used to screen for depression using the PHQ-9 in the elderly [Citation7]. Therefore, we use 6 as a cutoff point to screen for depression symptoms in our patients.

The World Health Organization reported that the overall prevalence of depression among the elderly ranged from 10% to 20% [Citation8]. In addition, a previous study reported prevalence rates of depression in patients with PCa before and after treatment of 17.4% and 18.4%, respectively [Citation9]. In the current study, the prevalence of depression symptoms in patients with PCa receiving ADT was 41%, which is higher than in other studies of patients with PCa [Citation9–11]. In addition, there was a positive correlation between the duration of ADT and PHQ-9 score in the patient with depression symptoms.

A previous study reported that patients with PCa receiving ADT had a higher risk of depression [Citation10]. Patients with PCa may have depression due to anxiety and stress about cancer-related issues, and ADT may further increase the severity of depression. Vahakn reported that the incidence of depression was similar between patients without cancer and those with PCa not receiving ADT (9.6% vs. 9.5%), but that it was significantly higher in patients with PCa receiving ADT (12.1%) in the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare database from 1992–1997 [Citation10]. In addition, Thomas et al reported that the prevalence of depression was 9.1% in patients receiving ADT with radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy, and that the patients receiving ADT were three times more likely to report experiencing depression compared to those receiving radiation therapy alone [Citation11]. In our study, a high proportion (41%) of the patients receiving ADT had depression, but tumor stage, initial PSA and Gleason score were not confounding factors contributing to depression.

A retrospective study including 400 patients with PCa receiving ADT over a mean follow-up period of 87 months reported that the duration of ADT may contribute to the development of psychiatric illnesses, and most commonly depression [Citation12]. Another study reported that patients with PCa receiving ADT had more severe depression [Citation13], and an Australian study reported that patients receiving ADT had an increased risk of developing depression (hazard ratio: 1.86, 95% confidence interval: 1.73–2.01) compared to patients not receiving ADT, and the hazard ratio was highest in the first year [Citation14]. In addition, a meta-analysis revealed that ADT for PCa was associated with a 41% increased risk of depression [Citation15]. In our study, there was no significant correlation between PHQ-9 score and duration of ADT in the patients receiving ADT overall (Pearson correlation: 0.13, p > .05). However, there was a positive correlation between PHQ-9 score and duration of ADT in the patients with depression symptoms (Pearson correlation: 0.4, p = .03). Of the patients with depression symptoms, a longer duration of ADT was significantly associated with a higher PHQ-9 score after adjusting for age, cancer stage, Gleason score, and initial PSA level, indicating that ADT may play an important role in the severity of depression symptoms.

A low testosterone level has been associated with depression in men [Citation16–18]. Kulej-Lyko et al. reported that testosterone deficiency was associated to the depression in patients with systolic heart failure [Citation17]. Monteagudo et al also reported that testosterone deficiency was related to depressive symptoms in obese men [Citation18]. Many studies have shown that androgen supplements seem to improve depressive symptoms [Citation19]. Both studies in the USA and in Japan reported that testosterone supplements in hypogonadal men improved their depression symptoms [Citation20,Citation21]. In our study, the average testosterone level was 0.23 ± 0.35 ng/ml, and there was no significant difference between the patients with and without depression (0.16 ± 0.17 ng/ml vs. 0.28 ± 0.43 ng/ml, p > .05). In addition, there was no significant correlation between testosterone level and PHQ-9 score in the correlation analysis (p > .05). This may because the testosterone level was suppressed to a very low level (<0.5 ng/ml) in all patients receiving ADT. This may also explain, at least in part, why there was a higher percentage of depression in this study.

ADT has many side effects including hot flashes, weight gain, fatigue, gynecomastia, breast tenderness, loss of body hair, and genital shrinkage, all of which may also contribute to depression. Hot flashes and chronic pain can cause sleep problems and lead to insomnia [Citation22], which has been associated with depression. Another study using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index and Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) reported that patients with PCa receiving ADT were more likely to have poorer sleep quality, be fatigued and more depressed [Citation23]. Weight gain, fatigue, breast tenderness and loss of body hair have also been associated with strong negative emotions which can also worsen depression [Citation24]. In the current study, more than half of the patients receiving ADT had sleeping problems (Q3) and appetite problems (Q5).

The result of our study revealed the correlations between Taiwanese patients with PCa receiving ADT and depression using the Chinese version of the PHQ-9. The average duration of ADT was long in this study (average 20 months), and our results showed that ADT played an important role in the severity of depression in the patients receiving ADT with depression symptoms. However, there are still some limitations to this study. First, this was a retrospective study and some factors such as the timing of the survey could not be controlled. Second, the number of patients was relatively small. Third, the lack of PHQ-9 scores before the patients received ADT. Fourth, there was no control group of patients who did not receive ADT for comparisons. Finally, not all comorbidities of the patients were recorded.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that in patients with PCa and depression symptoms, the severity of the depression symptoms was positively correlated with the duration of ADT. In contrast, this association was not found in patients without depression symptoms. Larger randomized studies with control groups are needed to verify these results. However, our results may serve as a reference for clinical urologists and physicians with regards to depression in patients with PCa receiving ADT, to prompt timely and appropriate psychiatric referral to optimize outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Pirl WF, Siegel GI, Goode MJ, et al. Depression in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a pilot study. Psycho-oncol. 2002;11:518–523.

- Roth AJ, Kornblith AB, Batel-Copel L, et al. Rapid screening for psychologic distress in men with prostate carcinoma: a pilot study. Cancer. 1998;82:1904–1908.

- Chung SD, Kao LT, Lin HC, et al. Patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer have an increased risk of depressive disorder. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173266.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744.

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613.

- Chen IP, Liu S-I, Huang H-C, et al. Validation of the patient health questionnaire for depression screening among the elderly patients in Taiwan. Int J Gerontol. 2016;10:193–197.

- Han C, Jo SA, Kwak JH, et al. Validation of the patient health questionnaire-9 Korean version in the elderly population: the Ansan Geriatric study. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:218–223.

- Sayers J. The world health report 2001 — Mental health: new understanding, new hope. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:1085–1085.

- Watts S, Leydon G, Birch B, et al. Depression and anxiety in prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence rates. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e003901.

- Shahinian VB, Kuo YF, Gilbert SM. Reimbursement policy and androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1822–1832.

- Thomas HR, Chen MH, D'Amico AV, et al. Association between androgen deprivation therapy and patient-reported depression in men with recurrent prostate cancer. Clin Genitourinary Cancer. 2018;16(4):313–317. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2018.05.007

- DiBlasio CJ, Hammett J, Malcolm JB, et al. Prevalence and predictive factors for the development of de novo psychiatric illness in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Can J Urol. 2008;15:4249–4256.

- Gagliano-Juca T, Travison TG, Nguyen PL, et al. Effects of androgen deprivation therapy on pain perception, quality of life, and depression in men with prostate cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:307–317.e1.

- Ng HS, Koczwara B, Roder D, et al. Development of comorbidities in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy: an Australian population-based cohort study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2018;21:403–410. doi:10.1038/s41391-018-0036-y

- Nead KT, Sinha S, Yang DD, et al. Association of androgen deprivation therapy and depression in the treatment of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urologic Oncol. 2017;35:664.e1–664.e9.

- Carnahan RM, Perry PJ. Depression in aging men: the role of testosterone. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:361–376.

- Kulej-Lyko K, Majda J, von Haehling S, et al. Could gonadal and adrenal androgen deficiencies contribute to the depressive symptoms in men with systolic heart failure? Aging Male. 2016;19:221–230.

- Monteagudo PT, Falcao AA, Verreschi IT, et al. The imbalance of sex-hormones related to depressive symptoms in obese men. Aging Male. 2016;19:20–26.

- Burris AS, Banks SM, Carter CS, et al. A long-term, prospective study of the physiologic and behavioral effects of hormone replacement in untreated hypogonadal men. J Androl. 1992;13:297–304.

- Wang C, Alexander G, Berman N, et al. Testosterone replacement therapy improves mood in hypogonadal men–a clinical research center study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3578–3583.

- Okada K, Yamaguchi K, Chiba K, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of androgen replacement therapy in aging Japanese men with late-onset hypogonadism. Aging Male. 2014;17:72–75.

- Savard J, Simard S, Hervouet S, et al. Insomnia in men treated with radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Psycho-oncol. 2005;14:147–156.

- Koskderelioglu A, Gedizlioglu M, Ceylan Y, et al. Quality of sleep in patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. Neurol Sci. 2017;38:1445–1451.

- Walker LM, Tran S, Robinson JW. Luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone agonists: a quick reference for prevalence rates of potential adverse effects. Clin Genitourinar Cancer. 2013;11:375–384.