Abstract

Objective

To assess the safety and effectiveness of percutaneous nephrolithotomy in aging male patients.

Methods

Two hundred eighty-three male patients over the years of forty undergoing percutaneous nephrolithotomy between December 2009 and September 2014 were evaluated, retrospectively. The patients were stratified by four age groups [40–49 (group-1), 50–59 (group-2), 60–69 (group-3), ≥70 years (group-4)]. The groups were compared regarding stone size, mean operation time, mean access number, mean nephrostomy removal time, hospitalization duration, stone-free rate, and complications rate. The patients were also evaluated with regard to glomerular filtration rate levels preoperatively and in the sixth month after surgery.

Results

Mean stone size was 810 ± 490 mm2 in group-1, 840 ± 500 mm2 in group-2, 845 ± 480 mm2 in group-3, and 800 ± 460 mm2 in group-4 (p = .02). There was no statistical difference between the four groups in terms of mean operation time, access number, hemorrhage, nephrostomy removal time, and hospital stay duration (p > .05). After additional interventions; no significant difference was detected for final stone-free rates among the groups (p = .12). A significant improvement was detected in glomerular filtration rate levels in the sixth month after surgery in all groups (p < .05).

Conclusion

These results indicate that percutaneous nephrolithotomy is a safe and effective method in aging male patients.

Introduction

Urinary system stone disease is one of the most frequent conditions in urology practice. In the general population, the prevalence of urinary tract calculi is approximately 2–3%, and the risk of developing kidney stones is around 12% [Citation1]. After the 1990s, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) became the first method of choice for large renal calculi along with improvements in endourology [Citation2]. PCNL, being a less invasive procedure, has a preponderance of positive features such as a shorter hospital stay and recovery period compared to open surgery [Citation3]. The success rate of PCNL depends on the anatomy of the kidney, the location of the stones, the size and number of stones, the comorbidities of the patients, and the experience of the surgeon [Citation4]. Besides these variables, aging could be considered as a challenging factor for PCNL, as the aging males might have accompanying chronic diseases and exert significant changes in body physiology [Citation5].

Given the advanced life expectancy, the prevalence of aging patients with renal stones encountered in urological practice is rising. Despite increasing numbers of scientific reports in last decades, studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of PCNL in aging male population is still sparse [Citation6–12]. There is still a need for data from different regions in this regard. Our center has been working with this procedure at a high volume for 20 years. As such, in this study, we aimed to present the outcomes of our single center experiences of PCNL in male patients over the age of forty years old assessing the success and complication rates as well as renal functional changes among the different age groups.

Material and methods

This study was carried out with the approval of the Okmeydanı Education and Research Hospital Ethics Committee dated September 23 2014 and numbered 235. Two hundred eighty-three male patients over the years of 40 undergoing percutaneous nephrolithotomy between December 2009 and October 2014 were evaluated, retrospectively.

All procedures were carried out under general anesthesia. Preoperative antibiotics were administered to patients with positive urine culture result according to the antibiotic susceptibility tests. First, a five or six French ureteral catheter was inserted into the affected kidney under direct vision of cystoscopy. Then, the patient was turned into a prone position. Access to the targeted calix was punctured with an 18-gauge needle, a guidewire was inserted, and then the urinary tract was dilated with a balloon dilatator (Nephromax, Microvasive Boston Scientific Corporation, Natick, MA) and a 30-F Amplatz sheath was replaced. A rigid, 26-F nephroscope was used for nephroscopy. The stones were fragmented by a pneumatic lithotripter (Vibrolith, Elmed, Ankara, Turkey) or an ultrasonic lithotripter (Swiss Lithoclast, EMS Electro Medical Systems, Nyon, Switzerland) and stone fragments were removed by the forceps. Upon the detection of no residual fragments, the operation was completed. A 16 F reentry or malecot nephrostomy was inserted in all patients. In selected solitary kidney patients, a DJ stent was inserted along with a malecot nephrostomy. A plain X-ray of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder (KUB) was obtained 24 h after the operation. In patients with stone-free and/or clinically insignificant residual fragments, the nephrostomy tube was removed on the postoperative second day after demonstrating no urinary leakage by antegrade nephrostogram.

We stratified the patients according to age category: 40–49 (group-1), 50–59 (group-2), 60–69 (group-3), and ≥ 70 years old (group-4). Height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) were evaluated as the demographic data of the patients. The simple stone was referred to as the location of stones in isolated renal pelvis or calyx while complex stones were referred to as complete and partial staghorn calculi. The size of the stone was calculated as mm2.

Patients were also classified for hydronephrosis as follows: patients with non-hydronephrosis or grade 1 hydronephrosis; and those with grades 2–3 hydronephrosis. The duration of the operation, the occurrence of pre-op bleeding that required a transfusion, the average number of percutaneous access, and complication rates were evaluated intraoperatively. The mean duration of hospital stay, the duration of nephrostomy, and the rate of the development of complications classified by Clavien complication category were assessed postoperatively. The stone-free rate was evaluated in two steps. The initial stone-free rate was evaluated with plain abdominal and pelvic radiography (KUB) for opaque stones and CT for non-opaque stones. The final stone-free rate was evaluated after the administration of the procedures including URS, ESWL, and re-PCNL. These parameters were compared in patients stratified by four age category.

The serum creatinine level of the sixth postoperative month and pre-op periods of the patients were identified. GFR was calculated using the Cockroft and Gault [Citation13] formula [(140 − age (years)×weight (kg)]/[72 × serum creatinine (mg/dL)]. A sixth postoperative month and pre-operative creatinine values in patients stratified by age category were compared within each age group.

Statistical analysis

The SPSS 20.0 software package (SPSS for Windows, 20.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used for normal distribution analysis. In case the data showed normal distribution, ANOVA was used for the comparison of the four age group. Otherwise, Kruskal-Wallis test was used. The Chi-square test was used for the examination of the qualitative data. The paired t test was used to analyze the perioperative and postoperative change in GFR level. The p values of less than 0.05 was deemed significant.

Results

Demographic features and stone characterization

Of 283 patients, 16 had a solitary kidney. Of the patients with solitary kidney, four had a solitary congenital kidney, 7 had a previous nephrectomy for a contralateral unit due to stones, renal tumor, infection, and trauma. Five patients were shown to have a nonfunctioning kidney by DMSA (dimercaptosuccinic acid) renal scintigraphy. Less than 15% in split renal function on a technetium 99 (Tc99) DMSA scan was evaluated as a nonfunctional kidney.

Mean BMI values in group 1, group 2, group 3, and group 4 were 27.2 ± 4.4, 26.9 ± 4.2, 28.5 ± 4.8, and 28.6 ± 4.4, respectively. Hypertension and diabetes mellitus rate were higher in more aged groups (p = .001). The mean ASA value of the patients in groups 1–4 were 1.75 ± 0.74, 1.89 ± 0.78, 2.07 ± 0.75, and 2.42 ± 0.92, respectively (p = .001).

Demographic features and stone characterization of the patients stratified by age category were depicted in .

Table 1. Demographic features and stone characterization of the patients stratified by age category.

Mean stone size was 810 ± 490 mm2 in group-1, 840 ± 500 mm2 in group-2, 845 ± 480 mm2 in group-3, and 800 ± 460 mm2 in group-4 (p = .02). 29 patients (29%) in group 1, 25 patients (30.1%) in group-2, 19 patients (34.5%) in group-3, and 13 patients (28.8%) in group-4 had complex renal stone. The detailed anatomical distributions of stones into the renal pelvicalyceal systems are demonstrated in .

Intraoperative and postoperative outcomes

The operation time of the patients in groups 1–4 were 68.3, 64.7, 70.3, and 69.7, respectively, and no statistically significant difference was observed (p = .12). The mean number of percutaneous access was 1.5 in group 1 and 3; 1.4 in group 2 and 4 with no difference between the two groups (p = .28). There was no significant difference between the four groups in the percentage of preoperative bleeding requiring a transfusion (p = .15). The duration of nephrostomy was longer in groups 2 and 3 with an insignificant difference (p = .08). Likewise, the mean hospital stay was comparable among the four groups (p = .25). Initial stone-free rates of the groups 1–4 were 82%, 84.3%, 81.8%, and 80% with significant difference (p = .04). After additional interventions such as URS and ESWL; no significant difference was detected among the groups (p = .12).

Minor complications (Clavien 1–2) were observed in 11% of the patients in group 1, 12% of the patients in group 2, 14.4% of the patients in group 3, and 13.2% of the patients in group 4. These rates were statistically similar among patient groups. Major complications (Clavien 3–4) were observed in 5% of the patients in group 1, 3.6% of the patients in group 2, 5.4% of the patients in group 3, 2.2% of the patients in group 4. Detailed information of intraoperative and postoperative data is provided in .

Table 2. Intraoperative and postoperative outcomes of the patients stratified by age category.

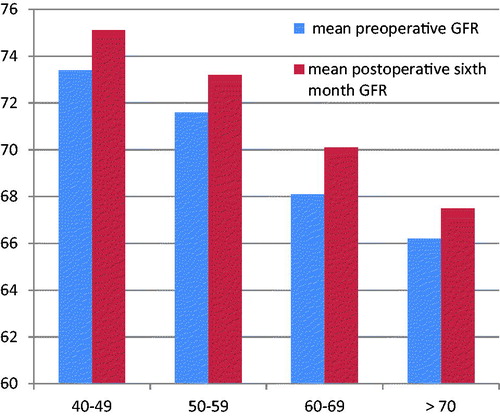

Mean preoperative GFR levels of the groups 1–4 were 73.4 ± 24.1, 71.6 ± 23.8, 68.1 ± 19.5, 66.8 ± 16.9, while postoperative sixth month GFR levels of the groups 1–4 were 75.1 ± 25.2, 73.2 ± 21.8, 70.1 ± 20.8, 67.5 ± 20.1 Significant improvements were detected in all groups (p < .05). demonstrates the change between preoperative and postoperative sixth-month GFR level among patients stratified by age category.

Discussion

PCNL has become a viable option in the treatment of kidney stones today, with advantages such as treatment success, low cost of treatment, shortened duration of hospital stay, and small scar tissue [Citation14]. In this study, we evaluated the safety and efficacy of PCNL in a more special subgroup-aging males.

From many aspects, surgery in the aging population has several difficulties. Age-related changes in the cardiovascular, pulmonary, nervous, metabolic, and locomotive systems that are frequently present in the elderly population may give rise to a range of complications and problematical outcomes [Citation15–17]. However, aging itself is not an illness, and chronological and biological age may be inconsistent. Furthermore, the existence of age-related changes may vary between organ systems in the same individual. These are suggestive for the fact that aging patients should be evaluated from an individualized perspective, taking into account the unique and more fragile habit of this special population.

The primary criterion for success at PCNL can be summarized as the ability to make the patient stone free with minimal morbidity. Striking this balance might be more challenging in elderly patients. Anagnostou et al. [Citation10] evaluated 779 patients who were assigned to two age category as younger (17–69 years) and elderly (≥70 years) participants. They found no statistical differences between the two groups concerning stone burden, complications, complete stone-free rates, and clinical success rates. Nakamon et al. [Citation7] also compared the success of PCNL in younger (51.42 years) and more aged (70.72 years) cohort. They observed that patients older than 65 years old had more comorbidities mainly diabetes mellitus, hypertension and a higher level of ASA classification. However, they reported no significant difference in the operative time, success rate, hospital stay and complications except sepsis episode between two groups. In our study, we also detected higher ASA score and chronic diseases (mostly diabetes mellitus and hypertension) in the aging male cohort, yet the intraoperative outcomes and complications rates were comparable among age groups. Only the initial stone-free rate was lower in aging patients, but after additional interventions, the final stone-free rates were also similar between groups.

Scientific evidence reported that PCNL is safe in elderly patients, yet most of them did not classify participants according to age category. Of the studies in which age stratification was conducted, Buldu et al. [Citation5] investigated the efficacy of PCNL in aging population comparing the participants over 60 and those under 60. They also subclassified the patients over 60 years old into three categories. They demonstrated that the mean duration of surgery, postoperative hematocrit drop, complication and success rate were statistically similar, but the length of hospital stay was significantly shorter in younger patients. Our results were similar to this study, but we also evaluated the solitary kidney patients and found similar success rate even in this unique population for all age groups.

Similarly, Sahin et al. [Citation6] compared the results of PCNL in 27 patients aged 60 years old or older with 178 patients younger than 60 years old. This study also included solitary kidney data, which was found more frequently in the more aged population. They demonstrated that the stone-free rate was similar in two groups, without any higher rates of complications or blood transfusions or more prolonged hospital stay and concluded that percutaneous nephrolithotomy is a safe and effective method of stone treatment in the elderly, even if they have a solitary kidney.

Although there is a great deal of clinical information about the technique and results of PCNL, there is not enough quantitative data about the effects of the PCNL procedure on renal function. In our study, as expected, the mean preoperative GFR level was lower in the more aged population. However, even in the elderly group (>70 years), the mean postoperative sixth-month GFR level was improved. Furthermore, we also included patients with the solitary kidney in the analysis and observed that solitary kidney patients had a stable or improved renal function after PCNL. These results are suggestive that PCNL is a safe procedure in even solitary kidney aging males, but the small sample size of our cohort should be certainly taken into account while interpreting these results.

Several limitations of the present study should be addressed. First, it is a retrospective study including a limited number of patients. This might reduce the reliability of the statistical analysis, but the outcomes were generally consistent. Second, the duration of fluoroscopy and estimated blood loss were not included in the study due to missing data. Additionally, we could not capture the biochemical analysis of the stones. Therefore, we were unable to make further investigation according to a chemical composition of the calculi.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that percutaneous nephrolithotomy is a feasible and safe treatment option for large renal calculi in aging male patients. Taking into account the small sample size of our cohort, well-designed studies with larger sample size are needed to confirm our results.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Johnson CM, Wilson DM, O’Fallon WM, et al. Renal Stone epidemiology: a 25-year study in Rochester, Minnesota. Kidney Int. 1979;16:624–631.

- Soucy F, Ko R, Duvdevani M, et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy for staghorn calculi: a single center’s experience over 15 years. J Endourol. 2009;23:1669–1673.

- Amiel J, Choong S. Renal Stone disease. The urological perspective. Nephron Clin Pract. 2004;98:54–58.

- Michel MS, Trojan L, Rassweiler JJ. Complications in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Eur Urol. 2007;51:899–906.

- Buldu I, Tepeler A, Karatag T, et al. Does aging affect the outcome of percutaneous nephrolithotomy?. Urolithiasis 2015;43:183–187.

- Sahin A, Atsü N, Erdem E, et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients aged 60 years or older. J Endourol. 2001;15:489–491.

- Nakamon T, Kitirattrakarn P, Lojanapiwat B. Outcomes of percutaneous nephrolithotomy: comparison of elderly and younger patients. Int Braz J Urol. 2013;39:692–701.

- Kuzgunbay B, Turunc T, Yaycioglu O, et al. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy for staghorn kidney stones in elderly patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2011;43:639–643.

- Okeke Z, Smith AD, Labate G, et al. Prospective comparison of outcomes of percutaneous nephrolithotomy in elderly patients versus younger patients. J Endourol. 2012; 26:996–1001.

- Anagnostou T, Thompson T, Ng C-F, et al. Safety and outcome of percutaneous nephrolithotomy in the elderly: retrospective comparison to a younger patient group. J Endourol. 2008;22:2139–2146.

- Akbari NR. Percutaneous nephrolithotripsy complication in the elderly. Aging Male. 2007;10:77–87.

- Doré B, Conort P, Irani J, et al. Comité Lithiase de l’Association Française d’Urologie Percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) in subjects over the age of 70: a multicentre retrospective study of 210 cases. Prog Urol. [Article in French]. 2004;14:1140–1145.

- Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41.

- Antonelli JA, Pearle MS. Advances in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Urol Clin North Am. 2013;40:99–113.

- Tonner PH, Kampen J, Scholz J. Pathophysiological changes in the elderly. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17:163–177.

- Priebe H. The aged cardiovascular risk patient. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:763–778.

- Sieber FE. Postoperative delirium in the elderly surgical patient. Anesthesiol Clin. 2009;27:451–464.