Abstract

Background: Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries are facing an epidemiological shift from infectious disease to chronic diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). CVDs incidence in SSA are frequently attributed to the prevalence of hypertension, diabetes, and overweight/obesity. Nevertheless, some researchers contend that CVDs are not a priority public health problem in SSA.

Method: This paper systematically reviews the evidence on CVDs and their relation with hypertension, diabetes mellitus and obesity/overweight in Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan and Tanzania. The publication’s content was analyzed qualitatively using the directed content analysis method and the results were presented in a tabular format.

Result: The paper illustrates the rising prevalence of CVDs as well as the three related risk conditions in the selected SSA countries.

Conclusion: The review indicates a poor health system response to the increasing risk of CVDs in SSA. The conditions and major drivers that contribute to this underlying increasing trend need to be further studied.

1. Introduction

Many Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries are experiencing increased urbanization and changes in population lifestyle that increase the incidence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), especially cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) [Citation1,Citation2]. According to Francesco and Michelle [Citation3], CVDs are attributable to risk factors such as smoking, saturated fat diet, physical inactivity, excessive alcohol consumption, psychosocial problems and others. These risk factors are mostly behavioral risks, which account for more than 60% of CVD deaths globally [Citation3,Citation4]. The effects of these risk factors may show up in individuals as risk conditions, namely hypertension, diabetes, and overweight/obesity. Prevention, early diagnosis and management of these risk conditions are imperative given the growing burden of CVDs in SSA. The relation between these three risk conditions and CVDs in SSA is the focus of this paper.

Mensah et al. [Citation5] noted that in SSA, the magnitude and trends in CVD deaths remain incompletely understood, which limits the formulation of data-driven regional and national health policies. In addition, most resources and attention of health policy-makers in the region are focused on infectious diseases [Citation6]. Although the WHO forecasts a rapid increase in the prevalence of CVDs in SSA by 2030, many researchers contend that the region is currently exempt from a CVDs epidemic and that CVDs is not a priority public health problem [Citation6].

The aim of this paper is to systematically review the trends in CVDs, and their association with the three risks conditions (hypertension, diabetes, and overweight/obesity) in selected SSA countries and to outline recommendations for future health policy. We included Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan and Tanzania in our review because the preliminary search showed availability of peer-reviewed articles for these countries. No such review with a focus on policy in SSA countries has been found in the literature. The review can support policy makers to develop regional and national strategies for health systems to be reoriented and readjusted to meet the specific challenge of CVDs, as well as other NCDs.

2. Methodology

We conducted online searches in PMC web, PubMed, BioMed, ScienceDirect, and international medical and clinical journals databases. We used the following combination of search terms: (1) country: Sub-Saharan Africa, Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan, or Tanzania; (2) CVDs: cardiovascular disease, heart disease, and CVDs. (3) conditions: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, overweight and obesity; and (4) policy: policy reforms, future policy. We considered synonyms and variations in spelling. Occasionally, we slightly modified the terms depending on the database technical requirements. The exact combination of terms used to search in PubMed is in Appendix A (supplementary data).

In the first screening phase, an initial selection was performed based on title and abstract taking into account the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented below. In the second screening phase, we reviewed the full text of the initially selected papers. We also screened the reference lists of all selected publications with the aim of identifying studies missed during the searches.

We selected only English language publications for further analysis, and included studies published between January 2010 and June 2017 (date of the last search). We considered publications as relevant if they reported on CVDs-related prevalence data, selected risk conditions, policies and reforms. We included both qualitative and quantitative studies; and in case of duplicate studies, we included the original publication. We excluded publications that provided general discussion of CVDs without presenting empirical data.

We analyzed the publication’s content qualitatively using the directed content analysis method and presented the results in a tabular format. We extracted information on the study design, methods of data collection (i.e. sample characteristics, data collection mode). We also extracted all major findings and results reported on CVDs prevalence in the selected SSA countries, the association of prevalence with the selected risks conditions, and the recommendations for health reforms related to observed CVDs trends.

We assessed the quality of the studies reviewed using quality appraisal checklists (see supplementary data), and we checked the quality of our review using the PRISMA checklist (Appendix A) (see supplementary data).

3. Results

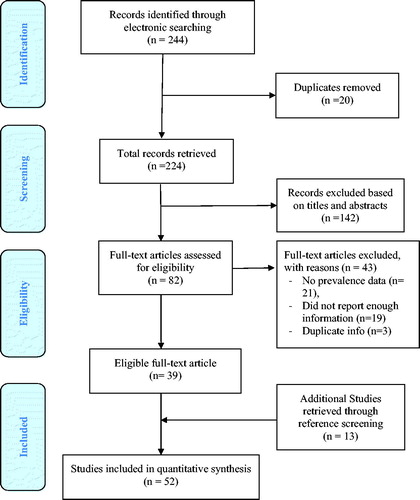

The PRISMA flow chart () outlines the steps we followed in retrieving relevant studies for the review. We identified 244 publications during the initial search. After the exclusion of duplicates and assessment of the articles’ titles and abstracts, we shortlisted 82 articles for detailed full-text analysis. However, 39 articles met the defined inclusion criteria and were included in the review. We retrieved 13 additional articles through reference screening of selected articles, bringing the total number of articles to 52.

General characteristics of articles

presents the general characteristics of the articles reviewed. Categorized by year of publication, 20 and 32 articles were published within 2010–2012 and 2013–2017 respectively. Total of 34 articles reported sampling conducted in the period 1990–2015, while the remaining did not report the actual period. All articles reported results from a single country except for one article. Publications reporting data from Nigeria predominated, while fewer articles reported data from the rest of the selected countries. More than half (34) studies had a descriptive aim, and 13 had explanatory aim, while seven had an exploratory aim.

Table 1. Characteristics of the reviewed publication.

Specifics of the study design

presents the data collection process and results of the quality assessment of the reviewed articles. The 52 articles reported sample sizes in the range from 60 to 19,289 participants Sample selection based on specific population subgroups was reported in 35 articles, reflecting the authors’ research interest in specific groups. Nine articles reported sample selection from the general population. About half of the articles (27) used data collected in cross-sectional studies, and 13 articles reported cohort designs. All articles reported one type of data collection methods. For CVDs prevalence estimation and CVDs risk conditions, a questionnaire was the most frequently used method. For CVDs and CVDs risk conditions frequency and occurrence, respondents were not the only source of data. Some articles provided systematic review analysis of existing datasets, (i.e. national surveys, disease registry data, journal articles, reports). Patient’s records were also used to gather data.

Table 2. Specificities of the study design.

Most articles (22) used descriptive statistics for data analysis (e.g. means, standard deviations, percentages, means, frequency distributions, numerical or mean values or proportions, median and interquartile range, descriptive cross-tabulations and bivariate analyses). Fifteen articles reported regressions analysis (e.g. multiple, linear, multivariate, univariate Cox proportional, binary, and means of Poison regression with robust variance). Twelve articles used tests for association (e.g., cross tabulation, Cronbach's coefficient, scatterplots, Pearson correlation coefficients, Spearman rank correlation coefficient or Spearman’s rho (rank) correlation and Pearson’s moment correlation). Eleven articles reported non-pragmatic test, and eight articles used estimation methods as an analytical technique. The rest of articles reported other statistical results (i.e. t-test 2-tailed hypothesis, optimal discriminant analysis – the effect strength for sensitivity).

We classified articles according to the validity, reliability and generalizability of the results. We considered a study reliable if the methods of data collection and analysis were well defined and potentially repeatable, and when multiple models or multiple samples produced comparable results. Based on this definition, 46 articles presented a reliable analysis; while the reliability of the analyses in the remaining articles (6) was uncertain. We considered studies with measures that led to valid conclusion or enabled valid inferences as valid. Based on this definition, 48 articles reported evidence that confirmed certain aspects of validity of the findings. The generalizability of the results was clear in 31 articles. Based on Appendix B (supplementary data), we graded the quality of 40 studies as high, and of 11 studies as medium and low.

Major findings of selected articles

We summarized the empirical findings on CVDs trends, risk conditions and related health reforms in the 52 articles (). The majority of publications (48) reported a significant increase in the prevalence of CVDs in the selected SSA countries. This increase in prevalence was reported to be high in all countries reviewed, namely Nigeria (29), Ghana (8), Sudan (8), South Africa (5) and Tanzania (2).

Table 3. Major findings reported in the review.

We observed Ischemic heart disease and stroke to be the major CVDs estimated health burden in Sudan, Nigeria and South Africa, respectively. Regarding the risk conditions and their association to CVDs prevalence, 40 articles reported that hypertension is relatively the largest contributor to CVDs burden. And 24 articles reported overweight/obesity as key contributor, while diabetes mellitus is reported in 11 articles. We observed a significant correlation between hypertension and increased overweight. Although behavior factors were not the focus of this review, 12 articles reported several behavioral risk factors of CVDs but not a major contributor in the SSA countries of focus, which included tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, dyslipidemia, physical inactivity, and environmental risks.

In most of the articles, the analysis solely focused on the epidemiological aspects of CVDs and not on the health policy aspects. Only three articles reported future health reforms and policies. These articles originated from Ghana and South Africa. For instance, Ghana’s Ministry of Health announced a paradigm shift from curative to preventive services to empower communities adopting healthy lifestyle. Also, a NCDs draft policy was developed in Ghana that places emphasis on prevention as a key dimension of reducing healthcare costs at the levels of individuals, families, health systems and government. Ghana also signed the United Nations (UN) agreement to a ‘whole of society, whole of government’ approach to tackle the NCDs crisis in developing countries. Furthermore, in South Africa, the department of health has prioritized the management of NCDs, in accordance with UN resolution that seeks to halt the increasing trends in premature deaths from NCDs.

Only seven articles reported health system responses to the increasing trend in CVDs. These responses included development of CVDs education and promotion programs, management programs targeting people with/or at risk of CVDs, CVDs risk conditions reduction, and improvement of CVDs related health infrastructure. For instance, in Nigeria, a massive hypertension population-oriented campaign aimed to increase physical activity and reduce salt intake was launched. Furthermore, on CVDs service improvement level, Nigeria has increased the availability of echocardiography lab and pediatrics cardiologists. In Ghana, the Ministry of Health included hypertension and diabetes in their priority health intervention list and provided free medication. In addition, NCDs control programs and regenerative health and nutrition programs were established, the latter addressed five dimensions of preventive health: diet, water intake, exercise, rest, and sanitation.

5. Discussion

Our review documented an increased prevalence of CVDs in the selected SSA countries [Citation8,Citation13,Citation14,Citation19,Citation24,Citation29]. These countries and others in the region are going through various phases of development [Citation15,Citation28,Citation30,Citation34] associated with social, economic, environmental and structural changes [Citation13,Citation30]. Moreover, as life expectancies rise due to economic development, CVDs prevalence is increasing, presenting new pressure on already struggling health systems. We found that hypertension, the major risk condition for CVDs, was most prevalent among the three CVDs risk conditions studied in our review [Citation9,Citation28,Citation32]. However, a high prevalence of diabetes and overweight/obesity was reported as well [Citation9,Citation15,Citation23,Citation37]. Our findings showed that the rising prevalence is not only an issue in high-income countries, but it is becoming an increasing health problem in SSA as well [Citation5,Citation15] which soon may constitute heavy social and economic burden. However, CVDs and associated risk conditions are remarkably neglected on the public health policy agendas in these countries with more attention given to infectious diseases. The absence of reliable information on CVDs and limited health policies might make it difficult for decision makers to appreciate the prevalence of CVDs [Citation19,Citation54]. In addition, health professionals in these countries are poorly trained in CVDs diagnosis and management, and health facilities lack appropriate diagnosis, monitoring and treatment equipment [Citation19,Citation27]. Poor patient’s knowledge about CVDs and related risk conditions might lead to late presentations at medical facilities and poor self-care [Citation8,Citation39,Citation49]. Hence, reorientation and adjustment of the healthcare system to the increased prevalence of CVDs is required. The findings of this review could draw the attention of policy makers for adequate health funding, resources allocation and research focus to CVDs, which in turn would allow the making of informed policies that would adequately adjust the health care system in SSA countries to address the rising trends of CVDs.

Strength and limitations

We included studies from Ghana, Nigeria, South Africa, Sudan and Tanzania, however, there was a significant country representation imbalance, with 58% of the studies reviewed conducted in Nigeria. Therefore, the result of this finding need to be confirmed when more data for the under-represented countries become available. Our analysis of CVDs trends and risk conditions in countries was based on the study’s year of publication. The use of year of publication compared to the actual period in which study/sampling was conducted, may introduce some bias, as there is a time lag between when a study is conducted and when it is finally published.

6. Conclusion

Our results showed that SSA countries included in this review demonstrate a rising prevalence of CVDs and related risk health conditions, namely diabetes, hypertension and overweight/obesity. The conditions and major drivers that contribute to this underlying increasing trend need to be further studied. A few studies in the selected SSA countries addressed health policies related to CVDs and indicated the risk of CVDs may further increase upon poor system response. These review results indicate an important gap in health policy in the selected SSA countries. Future longitudinal studies are needed to improve our understanding of the current situation and the evolution of CVDs and CVDs risk conditions.

Supplementary_material_.docx

Download MS Word (36.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Catherine K, Sonia SA. The impact of social determinants on cardiovascular disease. Can J Cardiol. 2010;26:8C–13C.

- Dalal S, Beunza JJ, Volmink J, et al. Non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa: what we know now. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:885–901.

- Francesco PC, Michelle AM. Cardiovascular disease and hypertension in sub-Saharan Africa: burden, risk and interventions. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11:299–305.

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2017 May [cited 2017 Dec 15]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs317/en/.

- Mensah GA, Roth GA, Sampson UK, et al. Mortality from cardiovascular diseases in sub-Saharan Africa, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis of data from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Cvja. 2015;26:S6–S10.

- Kariuki JK, Stuart-Shor EM, Leveille SG, et al. Methodological challenges in estimating trends and burden of cardiovascular disease in sub-Saharan Africa. Cardiol Res Pract. 2015;2015:921021.

- Victor MO, Ezekiel UN, Ifeoma IU, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in a Nigerian population with impaired fasting blood glucose level and diabetes mellitus. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:36.

- Adele B, Pretorius R, Carla MT, et al. The relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and knowledge of cardiovascular disease in African men in the North-West Province. Health SA Gesondheid. 2016;21:364–371.

- Eyitayo EE, Oluwole AB, Olusola OO, et al. Behavioural and socio-demographic predictors of cardiovascular risk among adolescents in Nigeria. J Health Sci. 2017;7:25–32.

- Ehab AM, Mohammed AM. Investigation risk factors of cardiovascular disease in Khartoum State, Sudan: Case-Control Study 2015. IJ SR. 2016;5:1593–1595.

- Daffalla AE, Rowydah M, Mohammed SA. Hypertension among women in Tiraira Madani, rural sudan, prevelance and risk factors, 2014. IJMHR. 2016;2:1–10.

- Franklin MO, Canice CE, Benneth CA, et al. Correlation on between central obesity and blood pressure in an adult Nigerian population. J Insulin Resistance. 2016;1:1–5.

- Kodaman N, Aldrich MC, Sobota R, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in Ghana during the rural-to-urban transition: a cross- sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162753.

- Mohammed AO, Mohamed EM, Abdulrahman AA, et al. Studying of heart diseases prevalence, distribution and cofactors in Sudanese population. Int J Res Med Sci. 2016;4:206–211.

- Ofori-Asenso R, Akosua AA, Amos L, et al. Overweight and obesity epidemic in Ghana-a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1239.

- Dahiru T, Ejembi CL. Clustering of cardiovascular disease riskfactors in semiurban population in Northern Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2013;16:511–516.

- Hadiza S, Musa KK, Basil NO. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among subjects with highnormal blood pressure in a Nigerian tertiary health institution. Sahel Med J. 2015;18:156–160.

- Richard WW, Ahmed J, Eric A, et al. Stroke risk factors in an incident population in urban and rural Tanzania: a prospective, community-based, case-control study. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1:282–288.

- De-Graft AA, Kushitor M, Koram K, et al. Chronic non-communicable diseases and the challenge of universal health coverage: insights from community-based cardiovascular disease research in urban poor communities in Accra, Ghana. BMC Public Health. 2014;14 Suppl 2:S3.

- Akintunde AA, Salawu AA, Opadijo OG. Prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors among staff of Ladoke Akintola University of Technology, Ogbomoso, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17:750–755.

- Commodore-Mensah Y, Samuel LJ, Dennison-Himmelfarb CR, et al. Hypertension and overweight/obesity in Ghanaians and Nigerians living in West Africa and industrialized countries: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2014;32:464–472.

- Khalid Y, Amira MH, Huda H, et al. Epidemiology of cardiac disease during pregnancy in Khartoum Hospital, Sudan. J Women’s Health Care. 2015;4:1–4.

- Obirikorang C, Osakunor DN, Anto EO, et al. Obesity and cardio-metabolic risk factors in an urban and rural population in the ashanti region-ghana: a comparative cross- sectional study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0129494.

- Odunaiya NA, Louw QA, Grimmer KA. Are lifestyle cardiovascular disease risk factors associated with pre-hypertension in 15–18 years rural Nigerian youth? A cross sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015;15:144.

- Nelson IO, Emmanuel CE, Basden JCO, et al. Pattern of cardiovascular disease amongst medical admissions in a regional teaching hospital in Southeastern Nigeria. Nig J Cardiol. 2013;10:77–80.

- Ogunmola JO, Olaifa OA, Akintomide AO. Assessment of cardiovascular risk in a Nigerian rural community as a means of primary prevention evaluation strategy using Framingham Risk Calculator. IOSR-JDMS. 2013;7:45–49.

- Ogunmola OJ, Antony OA. Mortality pattern of cardiovascular diseases in the medical wards of a tertiary health center in a rural area of EKITI state, southwest Nigeria. Asian J Med Sci. 2013;4:52–57.

- Ogah OS, Madukwe OO, Chukwuonye II, et al. Prevelance and determinanats of hypertension in ABIA state Nigeria: results from Abia state Non-communicable diseases and cardiovascular risk factors survey. Ethn Dis. 2013;23:161–167.

- Ogah OS, Sliwa K, Akinyemi JO, et al. Hypertensive heart failure in Nigerian Africans: insights from the abeokuta heart failure registry. J Clin Hypertens. 2015;17:263–272.

- Okon EE, Joseph A, Victor A, et al. Coronary artery disease and the profile of cardiovascular risk factors in South South Nigeria: a clinical and Autopsy Study. Cardiol Res Pract. 2014:2014:804751.

- Onwuchekwa AC, Tobin-West C, Babatunde S. Prevalence and risk factors for stroke in an adult population in a rural community in the Niger Delta, South-South Nigeria. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;32:505–510.

- Osuji CU, Onwubuya EI, Gladys Ifesinachi Osuji CU, et al. Pattern of cardiovascular admissions at Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital Nnewi, South East Nigeria. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;17:116.

- Otaigbe BE, Tabansi PN. Congenital heart disease in the Niger delta region of Nigeria: a four-year prospective echocardiographic analysis. Cvja. 2014;25:265–268.

- Peer N, Steyn K, Lombard C, et al. High burden of hypertension in the urban black population of Cape Town: The cardiovascular risk in Black South Africans (CRIBSA) Study. PLoS One. 2013;8;1-8.

- Prince OA, Elijah Y. Ageing and chronic diseases in ghana: a case study of Cape Coast Metropolitan Hospital. Int J Nurs. 2014;1:25–36.

- Sanuade OA, Anarfi JK, Aikins A, et al. Patterns of cardiovascular disease mortality in Ghana. A 5-year review of autopsy cases at Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. Ethn Dis. 2014;24:55–59.

- Somiya G. Obesity, dietary habits and coronary heart disease among sudanese patients attending Sudan Heart Center. IJSR. 2014;3:1285–1290.

- Oluyombo R, Olamoyegun MA, Olaifa O, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in semi-urban communities in southwest Nigeria: Patterns and prevalence. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2015;5:167–174.

- David AW, Motshedisi S, Mark EE, et al. The burden of antenatal heart disease in South Africa: a systematic review. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012;12:23.

- Ulasi II, Chinwuba KI, Obinna DO. A community-based study of hypertension and cardio-metabolic syndrome in semi-urban and rural communities in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:71.

- Salman ZD, Kirk G, DeBoer MD. High Rate of obesity-associated hypertension among primary schoolchildren in Sudan. Int J Hypertens. 2010;2011:629492.

- Walker R, Whiting D, Unwin N, et al. Stroke incidence in rural and urban Tanzania: a prospective, community-based study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:786–792.

- Rufus AA, Chidozie EM, Saidu AI, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in a low income semi-urban community in the North-East Nigeria. TAF Prev Med Bull. 2012;11:463–470.

- Agyemang C, Attah-Adjepong G, Owusu-Dabo E, et al. Stroke in Ashanti region of Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2012;46:12–17.

- Ejim EC, Okafor CI, Emehel A, et al. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in the middle-aged and elderly population of a Nigerian Rural Community. Trop Med J. 2011;2011:308687.

- Obinna IE, Cletus NA. A meta analysis of prevalence rate of hypertension in Nigerian populations. JPHE. 2011;3:604–607.

- Orluwene CG, Nnatuanya I. Association of metabolic biomarkers of cardiovascular disease in overweight and obese children in Emohua Local Government Area of Rivers State, Nigeria. JDMS. 2012;1:40–46.

- Grace J, Semple S. The prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors in normatensive, pre-hypertensive and hypertensive South African colliery executives. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2012;25:375–382.

- Isezuo SA, Sabir AA, Ohwovorilole AE, et al. Prevalence, associated factors and relationship between prehypertension and hypertension: A study of two ethnic African. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:224–230.

- Addo J, Agyemang C, Smeeth L, et al. A Review of population-based studies on hypertension in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2012;46:4–11.

- Kolo PM, Jibrin YB, Sanya EO, et al. Hypertension-related admissions and outcome in a tertiary hospital in Northeast Nigeria. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2010:1–6.

- Nwaneli CU. Changing trend in coronary heart disease in Nigeria. Afrimedic J. 2010;1:1–4.

- Okechukwu SO, Ikechi O, Innocent IC, et al. Blood pressure, prevalence of hypertension and hypertension related complications in Nigerian Africans: a review. World J Cardiol. 2012;4:327–340.

- Oladapo OO, Falase AO, Salako L, et al. A prevalence of cardiometabolic risk factors among a rural yoruba south-western nigerian population: a population-based survey. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2010;21:26–31.

- Marlien P, Robin D, Lucas N, et al. Risk factor profile of coronary artery disease in Black South Africans. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 2011;8:4–11.

- Suliman A. The state of heart disease in Sudan. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2011;22:191–196.

- Ahmed AA. Pattern of heart disease at AlShab Teaching Hospital; a decade into the new millennium. Sudan Med J. 2011;7:86–93.

- Sani MU, Wahab KW, Yusuf BO, et al. Modifiable cardiovascular risk factors among apparently healthy adult Nigerian population-a cross sectional study. BMC Res Notes 2010;3:11.