Abstract

Aim

Symptoms of cardiac arrhythmias and the perception of the implantation of a cardiac pacemaker can negatively affect mental health including sexuality and sexual behaviors. The aim of this study was to assess the attitude towards sexuality and sexual behaviors among men with cardiac arrhythmias.

Methods

The study included 80 men (aged 58.6 ± 9.23 years) with heart rhythm disorders who had qualified for cardiac pacemaker implantation. The International Index of Erectile Function IIEF-15 was completed at least one day before cardiac pacemaker implantation by all of the patients.

Results

The average results of the IIEF for all of the included patients was 41.87 ± 7.57 and were statistically worse in the population with atrioventricular blocks (39.60 ± 7.79) compared to those with sinus node dysfunction (44.15 ± 6.71) (p = .0110). The same relationships were found in the subcategory of orgasmic function (p = .0108) as well as intercourse satisfaction (p = .0111). Erectile dysfunction occurred in 88.75% of the patients with diagnosed arrhythmias. There was no statistically significant difference between the occurrence of erectile dysfunction in patients with sinus node dysfunction (87.5%) compared to patients with atrioventricular blocks (90%); p = .7236

Conclusion

We demonstrated that sexuality and sexual behaviors among men with cardiac arrhythmias was found to be statistically worse in the population with atrioventricular blocks compared to those with sinus node dysfunction. It was especially marked in the area of orgasmic function as well as for intercourse satisfaction.

Introduction

Cardiac arrhythmias are one of the biggest problems in modern cardiology. People all over the world have many symptoms that are connected with arrhythmias such as fluttering in the chest, tachycardia or bradycardia, dizziness or in the most advanced symptoms – syncope [Citation1,Citation2]. Due to the nature of these symptoms, they can all negatively affect the quality of life, which has been documented many times [Citation3,Citation4]. There are two main types of heart rhythm disorders – sinus node dysfunction and different types of atrioventricular blocks. Sinus node dysfunction, or sinoatrial node disease, is a group of abnormal heart rhythms that are caused by a malfunction of the sinus node, the heart’s primary pacemaker [Citation5]. Atrioventricular blocks (AV block) are a type of heart block in which the conduction between the atria and the ventricles of the heart is impaired [Citation6].

The most common, and sometimes, the only method for treating cardiac arrhythmias is cardiac pacemaker implantation, which eliminates/reduces the symptoms directly after implantation. Despite of lack of symptoms that are connected with arrhythmia, some patients still are afraid about life after pacemaker implantation. They are also afraid about their sex life after pacemaker implantation, which can cause other problems such as anxiety and depression [Citation7]. We believe that all of these symptoms and the perception of the implantation of an artificial device can negatively affect mental health. Some of the important elements that have not yet been well examined are the sexuality and sexual behaviors of patients with cardiac arrhythmias.

Aim of this study was to assess the attitude towards sexuality and sexual behaviors among men with cardiac arrhythmias who had qualified for cardiac pacemaker implantation.

Methods

The study was designed as prospective single center study. Eighty men with heart rhythm disorders who had been qualified for cardiac pacemaker implantation according to the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines were included [Citation8]. The study group was divided into two equal groups of 40 patients according to the type of indications for pacemaker implantation:

Group 1 – sinus node dysfunction – SND

Group 2 – atrioventricular blocks – AVB

Patients with heart rhythm disorders who had qualified for pacemaker implantation and agreed to participate in the survey were included. Patients who did not understand the questionnaire, who did not have sexual intercourse, and who did not have a permanent sexual partner were excluded as well as patients with previously diagnosed sexual dysfunctions. Patients with chronic kidney disease with glomerular filtration rate (GFR)<35 ml/min/1.7 m2, chronic cardiac failure in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III, IV with a history of myocardial infarction, and individuals with recognized psychiatric and hormonal disorders were also not qualified for the study.

The International Index of Erectile Function IIEF-15 was completed at least one day before cardiac pacemaker implantation in all of the patients that were included in the survey. This questionnaire is a validated, multi-dimensional and self-administered survey that has been found to be useful in clinical trials and the treatment outcomes in clinical trials. A score of 0–5 is awarded for each of the 15 questions that examine the four main domains of male sexual function: erectile function, orgasmic function, sexual desire, and intercourse satisfaction [Citation9].

Erectile function is assessed with six questions. The maximum possible score is 30 points. A score below 25 points is considered to be abnormal erectile dysfunction (ED). Orgasmic function is assessed based on two questions. The maximum number of points is ten. A score below nine points is considered to be abnormal. Sexual desire is assessed based on two questions. The maximum possible score is ten points. A score below nine points is considered to be abnormal. Intercourse satisfaction is assessed using three questions. The maximum possible score is 15 points. In this case, the cutoff value was 13 points. Overall satisfaction is assessed based on two questions. The maximum possible score is ten points. A score below nine points is considered to be abnormal.

Everyone included in the study was informed about their voluntary and anonymous status, and about the possibility of withdrawing from the study at any stage of the study. The local ethics committee of the Medical University of Silesia approved the study protocol. The study protocol complied with the version of the Helsinki Convention that was current at the time the study was designed.

Statistical analysis

MedCalc (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium) was used to perform the data analysis. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to check the normality of the distribution of the variables. The continuous data from the IIEF-15 are presented in points as the mean values and corresponding standard deviations. The Mann–Whitney test was used to calculate the comparison between the two groups. In addition, the χ2-test was used for selected nonparametric data when applicable. The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used to analyze the correlations. All of the statistical tests were considered to be significant at a p < .05.

Results

The study included 80 men (aged 58.6 ± 9.23 years) with cardiac arrhythmias who had qualified for cardiac pacemaker implantation. The characteristics of sexual functioning in all of the participants that were included in the study group that was divided into two groups depending on the types of cardiac rhythm disorders is presented in .

Table 1. Average values (overall and subscales) of the IIEF – International Index of Erectile Function in the entire population as well as in the SND and AVB subgroups.

The average results of the IIEF for all those included was 41.87 ± 7.57 and were statistically worst in the population with atrioventricular blocks (39.60 ± 7.79) compared to those with sinus node dysfunction (44.15 ± 6.71) (p = .0110). The same relationships were found in the subcategory of orgasmic function (p = .0108) as well as for intercourse satisfaction (p = .0111).

Erectile dysfunction occurred in 88.75% of the patients with diagnosed arrhythmias. There was no statistically significant difference between the occurrence of erectile dysfunction in patients with sinus node dysfunction (87.5%) compared to patients with atrioventricular blocks (90%); p = .7236. Moderate erectile dysfunction was more frequent in patients with atrioventricular blocks (17.5%) compared to patients with sinus node dysfunction (5%); p = .0768. Assessment of the occurrence of orgasm showed that only 3.75% of the patients were able to have an orgasm. The detailed results are presented in .

Table 2. Comparison between AVB and SND in the erectile function (EF) in the IIEF subcategory.

Severe orgasm disturbances were reported by 15% of patients. Four patients with atrioventricular blocks had difficulty in having an orgasm. Orgasmic disturbances occurred significantly more often in patients with atrioventricular blocks (27.5%) compared to patients with sinus node dysfunction (2.55%); p = .0017. Detailed data are presented in .

Table 3. Comparison between AVB and SND in the orgasmic function in the IIEF subcategory.

There were no statistically significant differences in sex desire depending on the type of arrhythmias. Patients had mild disorders in their sex desire (66.25%), while severe disorders were reported by 5% of the patients.

Assessment of the satisfaction with sexual intercourse showed that patients had a mild/moderate dysfunction. Severe dysfunction of sexual intercourse was statistically more frequent in patients with atrioventricular blocks compared to patients with sinus node dysfunction; p = .0028. Unfortunately, patients with cardiac arrhythmias did not have satisfactory sexual intercourse. The details are presented in .

Table 4. Comparison between AVB and SND in intercourse satisfaction in the IIEF subcategory.

An analysis of the overall satisfaction with their sex life showed that 20% of the patients exhibited normal, overall satisfaction with their sex life. Severe and moderate disturbances of their general satisfaction with their sex life were admitted by 20% and 22.5%, respectively.

Correlations

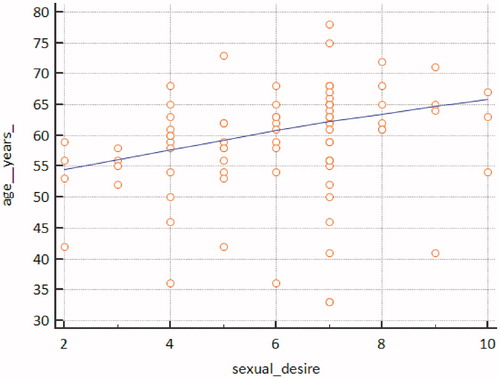

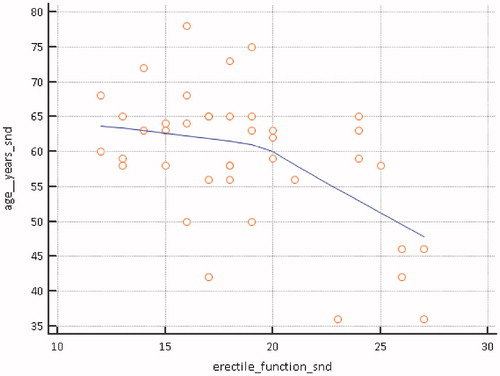

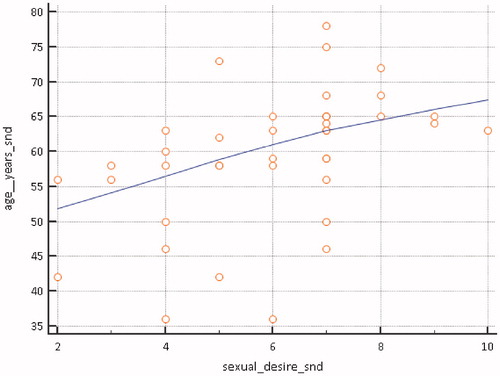

The influence of age on the occurrence of sexual dysfunctions showed that age affects the sex desire of men with cardiac arrhythmias (r = 0.2366, p = .0346) – . An analysis of the relationships among the groups with different types of cardiac arrhythmias showed that in the men with sinus node dysfunction, age affected the sex desire – the older the individual, the greater the sex desire (r= −0.5122, p = .0346) – and the younger the individual, the fewer disturbances in maintaining an erection (r = 0.4642, p = .0025) – . Such correlations have not been demonstrated in the patients with atrioventricular blocks.

Discussion

Proper sexual function requires the coordination of psychological, hormonal, vascular and neurological factors. The fear of having sexual intercourse due to cardiovascular diseases, including arrhythmias, coincides with a decrease in sexual desire, satisfaction and sexual frequency among men [Citation10–12]. After the occurrence of cardiovascular diseases including different types of arrhythmia with slow heart rhythm, there may be concern about sexual activity among those patients. Patients believe that physical sexual activity is harmful and dangerous to the heart and they are afraid of sudden death during sex. These fears significantly contribute to a decrease in the frequency of sex and consequently cause a cessation or delay in returning to sexual activity [Citation13,Citation14]. This can be observed not only in cardiovascular diseases but also in other like e.g. oncological diseases [Citation15].

Erectile dysfunction is the inability to achieve or maintain an erection long enough to have sexual intercourse. This situation applies to approximately 18% to 40% of men over 20 years of age [Citation16,Citation17]. In Poland, approximately 11% of men between 50 and 59 years of age, 4% of those aged 30 to 49, and 3% of those aged 18 to 24 suffer from erectile dysfunction [Citation18].

The relationship between erectile dysfunction and coronary artery disease (CAD) at the clinical level is supported by a common pathophysiological basis. The “artery size” hypothesis explains why CAD patients often report erectile dysfunction before detecting CAD [Citation19]. According to this hypothesis, for a given atherosclerotic burden, the smaller penile arteries become blocked earlier than the larger coronary arteries. The same concept works well in the absence of stenoses in the coronary arteries – a smaller penile artery has a larger endothelial surface and an erection requires a high degree of vasodilation compared to the arteries in other organs; the same degree of endothelial dysfunction may be symptomatic in these smaller vessels, but they are subclinical in larger vessels (i.e. coronary) [Citation20].

The physical requirements of sexual activity have been defined as light exercise with an ordinary partner compared to moderate physical activity in the range of three to four metabolic equivalent (METS) [Citation21,Citation22]. During the sex act, the heart rate rarely exceeds 130 bpm and systolic blood pressure rarely exceeds 170 mmHg in people with normal pressure.

The results of Leei et al. suggest that patients with erectile dysfunction have a significant vagal dysfunction and that the sympathetic dysfunction is systemic and not limited to the genital organs [Citation23]. Lavie et al. reported that a relative decrease in the parasympathetic system activity was associated with a dramatic increase in the sympathetic nervous system activity in patients with organic erectile dysfunction during sleep. Giuliano and Rampin suggested that the sympathetic pathways play a role in preventing erections, while the parasympathetic pathways play a pro-erective role. Patients with erectile dysfunction have excessive sympathetic activity. Disturbances in cardiac arrhythmias have co-occurring erectile dysfunction that is associated with a disturbance of the sympathetic nervous system, which was confirmed by our research [Citation24,Citation25].

Decreased sexual frequency and loss of libido can also predict a higher 10-year cardiovascular risk, what was documented by Ho et al in hypogonadal men [Citation26]. The incidence of erectile dysfunction increases with age and depends on many health and psychosocial factors. The conditions and states that are associated with erectile dysfunction include diabetes, hypertension, coronary heart disease, obesity, difficult micturition, low socioeconomic status, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, depression, subjectively reported premature ejaculation, low libido, and irregular intercourse [Citation27]. The lowest prevalence of erectile dysfunction is observed in men who do not have chronic conditions and live a healthy lifestyle. Erectile dysfunction can be seen as both a risk factor and a clinical manifestation of the progression of atherosclerosis [Citation28]. We also believe that substances like Testofen, a specialized Trigonella foenum-graecum seed extract can support sexual function in aging males [Citation29]. Rao et al. in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial examined influence of Trigonella foenum-graecum seed in 120 healthy men aged between 43 and 70 years of age. Authors concluded that Testofen is a safe and effective treatment for reducing symptoms of possible androgen deficiency, improves sexual function and increases serum testosterone in healthy middle-aged and older men. Unfortunately, additional research in patients with cardiac arrythmias is necessary to support our thesis.

Conclusions

We demonstrated that sexuality and sexual behaviors among men with cardiac arrhythmias was found to be statistically worse in the population with atrioventricular blocks compared to those with sinus node dysfunction. It was especially marked in the area of orgasmic function as well as for intercourse satisfaction. Assessment of the occurrence of orgasm showed that fewer than 5% of the patients with cardiac arrhythmias were able to have an orgasm.

Study limitations

The paper did not include women. Differences in sexuality and sexual behaviors between both genders are so elementary that we feel that the connection of analysis of these problems in both genders in one research is not appropriate.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Dagres N, Chao TF, Fenelon G, et al. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA)/Heart Rhythm Society (HRS)/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS)/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS) expert consensus on arrhythmias and cognitive function: what is the best practice? J Arrhythmia. 2018;34:99–123.

- Grisanti LA. Diabetes and arrhythmias: pathophysiology, mechanisms and therapeutic outcomes. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1669.

- Pyngottu A, Werner H, Lehmann P, et al. Health-related quality of life and psychological adjustment of children and adolescents with pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a systematic review. Pediatr Cardiol. 2019;40(1):1–16.

- Lopez-Villegas A, Catalan-Matamoros D, Lopez-Liria R, et al. Health-related quality of life on tele-monitoring for users with pacemakers 6 months after implant: the NORDLAND study, a randomized trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:223.

- Dobrzynski H, Boyett MR, Anderson RH. New insights into pacemaker activity: promoting understanding of sick sinus syndrome. Circulation. 2007;115:1921–1932.

- Hesse KA. Meeting the psychosocial needs of pacemaker patients. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1975;6:359–372.

- Mlynarska A, Mlynarski R, Golba KS. Anxiety, age, education and activities of daily living as predictive factors of the occurrence of frailty syndrome in patients with heart rhythm disorders. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22:1179–1183.

- Brignole M, Auricchio A, Baron-Esquivias G, European Society of Cardiology (ESC); European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy: the task force on cardiac pacing and resynchronization therapy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA). Europace. 2013;15:1070–1118.

- Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, et al. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822–830.

- Cook SC, Arnott LM, Nicholson LM, et al. Erectile dysfunction in men with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:1728–1730.

- Eyada M, Atwa M. Sexual function in female patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1373–1380.

- Kazemi-Saleh D, Pishgoo B, Farrokhi F, et al. Sexual function and psychological status among males and females with ischemic heart disease. J Sex Med. 2008;5:2330–2337.

- Nascimento ER, Maia AC, Pereira V, et al. Sexual dysfunction and cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review of prevalence. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2013;68:1462–1468.

- Kazemi-Saleh D, Pishgou B, Assari S, et al. Fear of sexual intercourse in patients with coronary artery disease: a pilot study of associated morbidity. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1619–1625.

- Taniguchi H, Kinoshita H, Koito Y, et al. Preoperative sexual status of Japanese localized prostate cancer patients: comparison of sexual activity and EPIC scores. Aging Male. 2017;20:261–265.

- Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. Am J Med. 2007;120:151–157.

- Shaeer O, Shaeer K. The Global Online Sexuality Survey (GOSS): the United States of America in 2011. Chapter I: erectile dysfunction among English-speakers. J Sex Med. 2012;9:3018–3027.

- Szymański FM, Puchalski B, Filipiak KJ. Obstructive sleep apnea, atrial fibrillation, and erectile dysfunction: are they only coexisting conditions or a new clinical syndrome? The concept of the OSAFED syndrome. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:701–707.

- Montorsi P, Montorsi F, Schulman CC. Is erectile dysfunction the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of a systemic vascular disorder? Eur Urol. 2003;44:352–354.

- Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Ioakeimidis N, et al. Arterial function and intima-media thickness in hypertensive patients with erectile dysfunction. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1829–1836.

- Nehra A, Jackson G, Miner M, et al. The Princeton III Consensus recommendations for the management of erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:766–778.

- Levine GN, Steinke EE, Bakaeen FG, et al. Sexual activity and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:1058–1072.

- Lee JY, Joo K-J, Kim 1JT, et al. Heart rate variability in men with erectile dysfunction. Int Neurourol J. 2011;15:87–91.

- Lavie P, Shlitner A, Nave R. Cardiac autonomic function during sleep in psychogenic and organic erectile dysfunction. J Sleep Res. 1999;8:135–142.

- Giuliano F, Rampin O. Neural control of erection. Physiol Behav. 2004;83:189–201.

- Ho CH, Wu CC, Chen KC, et al. Erectile dysfunction, loss of libido and low sexual frequency increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in men with low testosterone. Aging Male. 2016;19:96–101.

- Weber MF, Smith DP, O'Connell DL, et al. Risk factors for erectile dysfunction in a cohort of 108 477 Australian men. Med J Aust. 2013;199:107–111.

- Wełnicki M, Mamcarz A. Is erectile dysfunction an independent risk factor of coronary heart disease or another clinical manifestation of progressive atherosclerosis? Kardiol Pol. 2012;70:953–957.

- Rao A, Steels E, Inder WJ, et al. Testofen, a specialised Trigonella foenum-graecum seed extract reduces age-related symptoms of androgen decrease, increases testosterone levels and improves sexual function in healthy aging males in a double-blind randomised clinical study. Aging Male 2016;19:134–142.