Abstract

Background

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is a common issue among males, and the use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) therapy for treating ED has gained increasing attention, but there is still no conclusive evidence regarding its efficacy.

Aim

To evaluate the efficacy of PRP therapy for ED.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science databases up to November 2023 to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on PRP therapy for ED. We used Review Manager version 5.4 for data analysis and management.

Result

After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria for screening, a total of 4 studies involving 413 patients were finally included in our meta-analysis. According to our analysis, the PRP group showed significant advantages over the placebo group in terms of MCID at the first month (p = 0.03) and sixth months (p = 0.008), while there was no significant difference between the two groups at the third month (p = 0.19). Additionally, in terms of IIEF, PRP showed significantly better efficacy than placebo at the first, third, and sixth months (p < 0.00001).

Conclusions

PRP shows more effectiveness in treating ED compared to placebo, offering hope as a potential alternative treatment for ED.

Introduction

Erectile Dysfunction (ED) refers to a condition in which the penis is unable to achieve or maintain an erection to achieve sexual satisfaction [Citation1,Citation2]. It has brought distress to many men and become a contributing factor to marital discord. ED is a common condition worldwide, with high prevalence and incidence rates, affecting over 100 million men [Citation3,Citation4]. By the end of 2025, it is estimated that the total number of cases of ED worldwide will increase to 322 million [Citation5]. Currently, many treatment methods have been applied in clinical practice and have achieved some effectiveness in helping men alleviate this difficult condition, such as phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors (PDE5I), hormone therapy, intracavernosal injection, vacuum erection devices, and so on [Citation6]. However, they cannot achieve a curative effect or reverse the pathological process of ED.

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is plasma with a concentration of platelets that is higher than that of whole blood, obtained by centrifugation and separation [Citation7]. The concentration of platelets is at least two to three times higher than normal plasma [Citation8]. PRP contains numerous cellular factors, cell adhesion molecules, chemotactic factors, and growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), and epidermal growth factor (EGF) [Citation9,Citation10]. Additionally, it also contains proteins such as fibrin scaffolds. These bioactive factors promote cell proliferation and differentiation, facilitate vascular formation and maturation, and play a crucial role in collagen production and tissue repair [Citation8,Citation11]. The bioactive substances rich in PRP may be beneficial for the repair of penile injuries, representing a potential mechanism for treating ED and opening up new avenues for its treatment.

PRP therapy, as a form of regenerative medicine, has gained increasing attention. People have started exploring its application in the treatment of ED and some promising results have been achieved. However, certain regulatory bodies, such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) remain skeptical and have not yet approved its use for injection [Citation10]. Furthermore, although PRP has been commercially utilized in some places, its use for treating ED is generally not covered by government or private insurance companies. As a result, men seeking PRP treatment for ED may have to bear the significant cost of such therapy and face uncertain risks [Citation12]. Hence, we decided to conduct this meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of PRP in treating ED, aiming to provide some reference for assessments conducted by relevant institutions.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We conducted a literature search according to our exclusion and inclusion criteria, and reported the results of the meta-analysis in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [Citation13]. As of April 2024, we have retrieved all the published English-language articles on the efficacy of PRP in the treatment of ED in major databases including PubMed, Embase, Cochrane library database, and Web of science. The keywords and search string we use are as follows: “platelet-rich plasma” AND (“erectile dysfunction” OR “male impotence” OR “male sexual impotence”" OR “impotence”). This systematic review and meta-analysis have been published on PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews, and the ID is CRD42023480632. Two reviewers independently screen the titles and abstracts, and then evaluate the full text to determine if the research is suitable for inclusion. Differences are resolved through discussion, and if consensus cannot be reached, a third reviewer is consulted.

Study selection

A study needs to meet the following criteria to be included in our meta-analysis:(1) Patients: The involved patients should be males with ED; (2) Intervention: The intervention people received should include intracavernous injection of PRP; (3) Comparison: Patients in the control group received placebo, or another treatment measure in the experimental group other than PRP.; (4) Outcome: The outcome indicators should be able to extract accurate data and include the following contents: the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) and the minimal clinically important difference (MCID); (5) Study: The study type should be a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

The following studies would be excluded: (1) Patients who have undergone major pelvic or penile surgery, or those with abnormal testosterone levels; (2) Studies with no data or incomplete data; (3) Studies that are not RCT.

Quality assessment

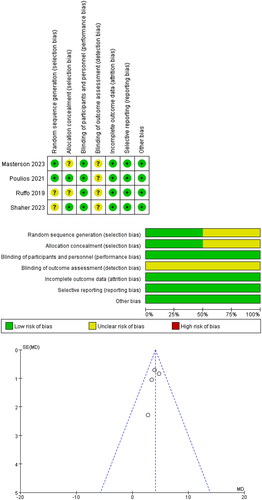

The Cochrane bias risk tool is used for quality assessment of included studies. It evaluates the quality of included literature from seven aspects: (1) random sequence generation; (2) allocation concealment; (3) blinding of participant and personnel; (4) blinding of outcome assessment; (5) incomplete outcome data; (6) selective reporting; (7) other bias. The risk assessment for each aspect includes “high risk”, “low risk”, and “unclear risk”. The Review Manager version 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration, London, UK) was used to facilitate the quality assessment process. Two reviewers conducted the quality assessment, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion among the authors to reach a consensus.

Data extraction

Two reviewers extract data from the article and organize it using Excel spreadsheets. The following data needs to be extracted from the articles:(1) The authors and country of the article; (2) Patients information; (3) Details of the interventions received by patients, and the duration of the study; (4) Information on outcome measures, including MCID and IIEF. MCID is derived from the IIEF score and is defined to be an improvement of 2 or more points in the IIEF for patients with mild or mild-to-moderate ED, or an improvement of 5 or more points in the IIEF for patients with moderate ED.

Statistical analysis

We used Review Manager version 5.4 for data processing and summarized the evidence of the efficacy of PRP in treating ED according to the Cochrane Intervention Systematic Review Handbook. The differences in MCID and IIEF between baseline and the 1st, 3rd, and 6th months were analyzed. For continuous data, we used mean differences (MD) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for comparisons, and they were expressed as the means ± standard deviations (SD). For dichotomous data, we calculated the odds ratio (OR) and 95% CI using the Mantel − Haenszel method, and they were expressed as numbers. We assessed heterogeneity using p values and I-squared. If the p value < 0.05 and I-squared > 50%, it indicates significant heterogeneity, so we used a random-effects model. If the p value > 0.05 and I-squared < 50%, it indicates low heterogeneity, so we used a fixed-effects model. In addition, if the final result shows p < 0.05, it indicates that the difference is statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the individual studies

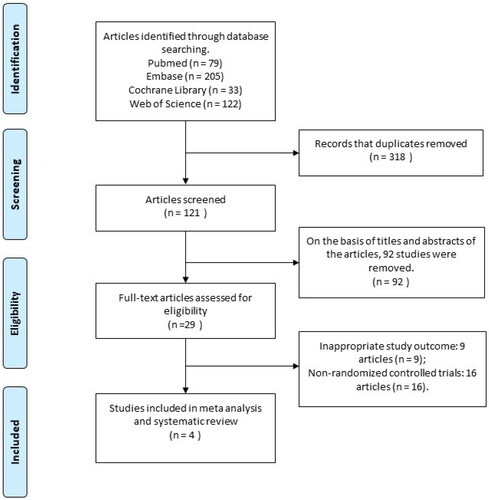

By searching four databases, a total of 413 articles were identified. After removing duplicates and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria for screening, four RCTs were ultimately included in our meta-analysis [Citation14–17]. A total of 343 male patients with ED were involved. The flowchart of the literature search process is presented in . Detailed information on individual studies is provided in .

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Quality of the individual studies

All included studies were RCTs. All studies conducted double-blinding for both healthcare staff and patients. Two studies described the method of generating random sequences, and two studies explicitly implemented allocation concealment. No study provided detailed information on blinding for outcome assessment. The specific details of the quality assessment results and publication bias assessment are shown in .

Efficacy

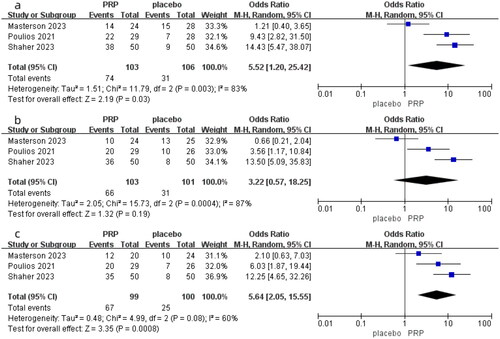

MCID at the first month

Three studies in total compared the difference in MCID after one month of PRP and placebo treatment for ED, involving 209 patients (103 in the PRP group and 106 in the placebo group). As shown in , due to I-squared = 83% and p = 0.003, indicating significant heterogeneity, we chose a random-effects model. The results of the meta-analysis showed an OR = 5.52, 95% CI was 1.20–25.42, and p = 0.03. This result indicates that there is a statistically significant difference in MCID between PRP and placebo in terms of MCID at first month, and the therapeutic effect of PRP on ED is superior to placebo.

MCID at the third month

Three studies compared the difference in MCID between the PRP group and the placebo group after treating ED for three months. As shown in , due to significant heterogeneity among the studies (I-squared = 87% and p = 0.0004), we chose a random-effects model to analyze the data. In the results of the meta-analysis, the OR was 3.22, with a 95% CI ranging from 0.57 to 18.25, and p = 0.19. This result indicates that there is no significant difference between PRP and placebo in terms of MCID at the third month, suggesting that the therapeutic effect of PRP on ED is not superior to placebo.

MCID at the sixth month

There were three studies compared the differences in MCID between the PRP group and the placebo group at the sixth month. As shown in , due to significant heterogeneity among the three studies (I-squared = 60% and p = 0.08), a random-effects model was chosen to analyze the data. In the meta-analysis results, the OR was 5.64 with a 95% CI of 2.05–15.55, and a p value of 0.0008. These results indicate that there is a statistically significant difference in MCID between PRP and placebo at the sixth month, suggesting that the therapeutic effect of PRP on ED is superior to placebo.

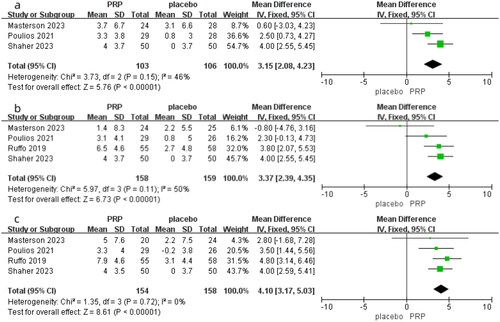

IIEF at the first month

Three studies compared the differences in IIEF between the PRP group and the placebo group after one month of treating ED, involving 209 patients (103 in the PRP group and 106 in the placebo group). As shown in , with I-squared = 46% and p = 0.15, indicating no significant heterogeneity, a fixed-effects model was selected. In our meta-analysis results, the MD was 3.15 with a 95% CI of 2.08 to 4.23, and p < 0.00001. The results indicate a significant difference between PRP and placebo, suggesting that the therapeutic effect of PRP on ED is significantly superior to placebo in the first month.

IIEF at the third month

The four studies compared the differences in IIEF between the PRP group and placebo group after three months of treatment, involving a total of 317 patients (158 in the PRP group and 159 in the placebo group). As shown in , due to an I-squared value of 50% and a p value of 0.11, indicating no significant heterogeneity, a fixed-effect model was used. In our meta-analysis, the MD was 3.37 with a 95% CI of 3.29–4.35, and p < 0.00001. The results suggest a statistically significant difference in IIEF between the PRP and placebo groups, indicating that PRP therapy for ED is significantly more effective than placebo after three months of treatment.

IIEF at the sixth month

All four studies compared the differences in IIEF between the PRP group and placebo group after six months of treating ED. As shown in , with an I-squared value of 0 and a p value of 0.72, it indicates no heterogeneity among the studies, so a fixed-effects model was used. In our meta-analysis, the MD was 4.10 with a 95% CI of 3.17–5.03, and p < 0.00001. It demonstrates a statistically significant difference in IIEF between the PRP and placebo groups after six months, indicating that PRP treatment for ED is significantly more effective than placebo.

Discussion

ED is commonly believed to primarily affect middle-aged and elderly men over the age of 40, with its prevalence increasing with age [Citation18,Citation19]. However, research has found that 14.2% of sexually active men aged 18–31 in the United States also experience mild to severe ED [Citation20]. ED is the result of disruptions in the complex interplay between vascular and neural processes that are responsible for achieving and maintaining an erection. When arousal occurs, parasympathetic activity triggers the release of nitric oxide and an increase in intracellular cyclic guanosine monophosphate, leading to vascular smooth muscle relaxation, and enhanced blood flow into the corpora cavernosa [Citation21]. Any disruption in any part of the process can lead to ED. Additionally, psychological factors may also lead to ED. ED is closely associated with the presence of many diseases, such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, hyperuricemia, rheumatic diseases, etc. [Citation18,Citation22]. Additionally, medications used for these diseases may also lead to ED. Unhealthy lifestyle choices, such as smoking, sedentary behavior, and chronic alcohol consumption are also related risk factors [Citation23]. Therefore, improving lifestyle habits is often the first step in treating ED. Apart from lifestyle changes, PDE5 inhibitors are currently the most popular treatment method. However, an increasing number of patients are seeking other treatment methods due to ineffectiveness or adverse reactions [Citation24]. PRP has received a lot of attention for its potential to reverse pathology, but there is currently a lack of strong clinical evidence to support it.

In fact, as early as the 1970s, the concept of PRP was proposed, primarily for treating patients with thrombocytopenia [Citation25]. Subsequently, PRP began to be widely applied in various medical fields. Nowadays, research on PRP treatment for various diseases can be seen in fields, such as reproductive medicine, dentistry, dermatology, gynecology, and orthopedics [Citation26–30]. The use of intracavernous injection of PRP for the treatment of human ED is relatively new and has primarily focused on the past decade. Initially, experiments were conducted on rats. In 2009, Ding et al. discovered that PRP could promote cavernous nerve regeneration and restore erectile function in a rat model [Citation31]. Subsequently, Wu, Liao, and others confirmed the positive effects of intracavernous PRP injection on the restoration of erectile function in rat models [Citation32–34]. Wu’s research also demonstrated the important role played by cytokines and other bioactive factors in this process [Citation35]. Although the potential of PRP treatment for ED has been demonstrated in rat models, further considerations are needed before its clinical application. However, there are now some regions where PRP has been commercially utilized and marketed under the name “P-shot”.

We conducted this meta-analysis in the hope of providing useful information for the clinical application of PRP in treating ED. And this is the first meta-analysis studying the effectiveness of PRP treatment for ED. We evaluate the efficacy using two outcome measures: MCID and IIEF. In our analysis, we found that the differences in MCID between the PRP group and the placebo group at the first month (p = 0.03) and sixth month (p = 0.008) were statistically significant, but there was no statistical difference at the third months (p = 0.19). As for IIEF, the differences between the PRP group and the placebo group at one month (p < 0.00001), three months (p < 0.00001), and six months (p < 0.00001) were all statistically significant. Based on our results, intracavernous injection of PRP seems to be a promising treatment option for ED. Compared with placebo, it shows significant advantages in IIEF, as well as MCID at the first and sixth months. However, PRP did not demonstrate a significant advantage in terms of MCID at the third month, despite the IIEF at the third month being significantly better than the placebo. This may be attributed to several factors. MCID refers to an increase of at least 2 points in the IIEF score for patients with mild or mild to moderate ED (ED) (IIEF score: 17–25), or an increase of at least 5 points for patients with moderate ED (IIEF score: 11–16). The lack of a significant difference in MCID at the third month may be due to the improvement in IIEF not meeting the requirements for MCID. Additionally, the absence of Ruffo’s data might also contribute to the lack of a significant difference. Although the MCID results at the third month were not favorable, the overall trend is positive. Furthermore, from the forest plot of IIEF, we found that the MD values are gradually increasing at one, three, and six months. In the forest plot of MCID, the MD value at six months is also greater than at one month. This suggests that the effectiveness of PRP treatment for ED may gradually improve over time.

PRP as a regenerative therapy aims not only to treat symptoms but primarily to restore the structure and function of the diseased penile tissue. PRP is rich in various growth factors, such as nerve growth factor (NGF), which can promote the repair and regeneration of damaged nerves. This is particularly important for ED caused by nerve damage, as improving nerve function can enhance erectile response [Citation36]. And VEGF can stimulate the formation of new blood vessels, improving blood flow to penile tissue, which is crucial for achieving and maintaining an erection [Citation37]. Additionally, the growth factors in PRP can promote the proliferation and repair of penile smooth muscle cells, the health of which is vital for controlling vascular dilation and the erectile process. PRP also has natural anti-inflammatory properties, which can alleviate inflammation in penile tissue, a possible contributing factor to ED. Lastly, the growth factors in PRP can stimulate the synthesis of collagen and the proliferation of tissue cells, helping to improve the structure and function of penile tissue [Citation8,Citation11]. These potential mechanisms, combined with our meta-analysis results, offer promising prospects for PRP treatment of ED.

It is worth noting that as an autologous product, PRP does not have clear side effects. Due to the patient’s own cells are used, it will not cause an immune response, and also minimizes the chance of blood-borne contamination. The four studies we included did not report any other complications such as bleeding or pain. Additionally, in Poulios’ study, the placebo group reported more pain, while the subjects receiving PRP showed higher satisfaction. This may be related to the analgesic effect of PRP. Various pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators released by activated platelets can alleviate inflammation and pain, and the 5-HT system may also play a key role in this process [Citation27,Citation38]. The analgesic effect of PRP is also evident in other diseases [Citation39,Citation40]. However, overall, the existing evidence cannot conclusively determine the specific functions and mechanisms of action of PRP. Apart from these four RCTs, other relevant clinical studies that have been published have also not found any significant adverse reactions [Citation41,Citation42]. Although PRP itself is not problematic, some specific populations may not be suitable for PRP treatment. Research has indicated that patients with platelet functional disorders, unstable hemodynamics, anticoagulation, or sepsis are not recommended for PRP therapy [Citation10]. In short, the safety of PRP in treating ED is reassuring, and there have been no significant side effects reported so far.

Our research also faces some limitations. Firstly, the preparation of PRP is not standardized. Due to the lack of unified regulations regarding the formulation and components of the injected PRP, as well as variations in the platelet separation devices used, the consistency of PRP injected into the corpora cavernosa in different experiments cannot be guaranteed. This means that the proportions and concentrations of platelets, growth factors, and cytokines in PRP vary. Although some have proposed a classification system for PRP, it is regrettable that a consensus has not yet been reached [Citation43,Citation44]. It is difficult to determine whether this has had a significant impact on the generalizability of the conclusions. Furthermore, there are flaws in the characteristics of the patients included in the study, making it difficult to determine whether the patients have organic ED or psychogenic ED. Another limitation is the variation in RCTs regarding the injection of PRP, including dosage and interval time. The non-standardization of administration is also an urgent issue that needs to be addressed. Unfortunately, the optimal dosage for administration cannot be determined at this time. Additionally, the number of RCTs included in our study was limited, with only four studies involving a total of 343 patients. More high-quality RCTs with large sample sizes are needed. The follow-up period for all four RCTs was only 6 months, and having a longer follow-up period would be more favorable for evaluating long-term differences. Finally, the impact of loss to follow-up should also be taken into consideration.

Conclusion

In conclusion, PRP therapy for ED has shown promising efficacy and holds the potential to become a new alternative treatment option for ED patients. Furthermore, it has demonstrated good safety with no significant side effects reported. However, due to various limitations, more high-quality RCTs are needed to provide further evidence, and standardization of PRP procedures should also be a focus for future efforts.

Ethics statement

No ethics to disclose.

Author contributions statement

Conceptualization: Yuanshan Cui. Data curation: Qiancheng Mao, Yingying Yang. Formal analysis: Qiancheng Mao, Yang Liu, Gonglin Tang. Funding acquisition: Jitao Wu, Yuanshan Cui. Investigation: Qiancheng Mao Hongquan Liu. Methodology: Qiancheng Mao, Yingying Yang. Project administration: Yushan Cui. Resources: Qiancheng Mao. Software: Qiancheng Mao, Xiaofeng Wang. Supervision: Yuanshan Cui, Jitao Wu. Writing – original draft: Qiancheng Mao, Yingying Yang. Writing – review and editing: Yuanshan Cui.

Acknowledgments

None.

Disclosure statement

All authors had no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Britt D, Blankstein U, Lenardis M, et al. Availability of platelet-rich plasma for treatment of erectile dysfunction and associated costs and efficacy: a review of current publications and Canadian data. Can Urol Assoc J. 2021;15:202–206.

- Salonia A, Bettocchi C, Boeri L, et al. European association of urology guidelines on sexual and reproductive health-2021 update: male sexual dysfunction. Eur Urol. 2021;80:333–357.

- McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Lewis R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of sexual dysfunction in women and men: a consensus statement from the fourth international consultation on sexual medicine 2015. J Sex Med. 2016;13(2):144–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.034.

- Eardley I. The incidence, prevalence, and natural history of erectile dysfunction. Sex Med Rev. 2013;1(1):3–16. doi: 10.1002/smrj.2.

- Islam MM, Naveen NR, Anitha P, et al. The race to replace PDE5i: recent advances and interventions to treat or manage erectile dysfunction: evidence from patent landscape (2016-2021). J Clin Med. 2022;11(11):3140. doi: 10.3390/jcm11113140.

- Alonso-Isa M, García-Gómez B, González-Ginel I, et al. Conservative non-surgical options for erectile dysfunction. Curr Urol Rep. 2023;24(2):75–104. doi: 10.1007/s11934-022-01137-2.

- Marx RE. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP): what is PRP and what is not PRP? Implant Dent. 2001;10:225–228.

- Gupta S, Paliczak A, Delgado D. Evidence-based indications of platelet-rich plasma therapy. Expert Rev Hematol. 2021;14(1):97–108. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2021.1860002.

- Pochini AdC, Antonioli E, Bucci DZ, et al. Analysis of cytokine profile and growth factors in platelet-rich plasma obtained by open systems and commercial columns. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2016;14:391–397.

- Ramaswamy Reddy SH, Reddy R, Babu NC, et al. Stem-cell therapy and platelet-rich plasma in regenerative medicines: a review on pros and cons of the technologies. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2018;22(3):367–374. doi: 10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_93_18.

- Jain NK, Gulati M. Platelet-rich plasma: a healing virtuoso. Blood Res. 2016;51(1):3–5. doi: 10.5045/br.2016.51.1.3.

- Scott S, Roberts M, Chung E. Platelet-Rich plasma and treatment of erectile dysfunction: critical review of literature and global trends in platelet-rich plasma clinics. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(2):306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.12.006.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Ruffo A, Franco M, Illiano E, et al. Effectiveness and safety of platelet rich plasma (PrP) cavernosal injections plus external shock wave treatment for penile erectile dysfunction: first results from a prospective, randomized, controlled, interventional study. Eur Urol Suppl. 2019;18(1):e1622–e1623. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(19)31175-3.

- Shaher H, Fathi A, Elbashir S, et al. Is platelet rich plasma safe and effective in treatment of erectile dysfunction? Randomized controlled study. Urology. 2023;175:114–119. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2023.01.028.

- Poulios E, Mykoniatis I, Pyrgidis N, et al. Platelet-Rich plasma (PRP) improves erectile function: a Double-Blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Sex Med. 2021;18(5):926–935. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.03.008.

- Masterson TA, Molina M, Ledesma B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of erectile dysfunction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J Urol. 2023;210(1):154–161. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000003481.

- Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. Am J Med. 2007;120(2):151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.010.

- Yafi FA, Jenkins L, Albersen M, et al. Erectile dysfunction. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2(1):16003. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.3.

- Calzo JP, Austin SB, Charlton BM, et al. Erectile dysfunction in a sample of sexually active young adult men from a US Cohort: demographic, metabolic and mental health correlates. J Urol. 2021;205(2):539–544. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001367.

- Irwin GM. Erectile dysfunction. Prim Care. 2019;46(2):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2019.02.006.

- Seftel AD, Sun P, Swindle R. The prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus and depression in men with erectile dysfunction. J Urol. 2004;171(6 Pt 1):2341–2345. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000125198.32936.38.

- Grover SA, Lowensteyn I, Kaouache M, et al. The prevalence of erectile dysfunction in the primary care setting: importance of risk factors for diabetes and vascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(2):213–219. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.2.213.

- Wang CM, Wu BR, Xiang P, et al. Management of male erectile dysfunction: from the past to the future. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1148834. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2023.1148834.

- Alves R, Grimalt R. A review of platelet-rich plasma: history, biology, mechanism of action, and classification. Skin Appendage Disord. 2018;4(1):18–24. doi: 10.1159/000477353.

- Sharara FI, Lelea L-L, Rahman S, et al. A narrative review of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) in reproductive medicine. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;38(5):1003–1012. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02146-9.

- Everts PA, van Erp A, DeSimone A, et al. Platelet rich plasma in orthopedic surgical medicine. Platelets. 2021;32(2):163–174. doi: 10.1080/09537104.2020.1869717.

- Streit-Ciećkiewicz D, Kołodyńska A, Futyma-Gąbka K, et al. Platelet rich plasma in gynecology-discovering undiscovered-review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:5284.

- Peng GL. Platelet-Rich plasma for skin rejuvenation: facts, fiction, and pearls for practice. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2019;27(3):405–411. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2019.04.006.

- Xu J, Gou L, Zhang P, et al. Platelet-rich plasma and regenerative dentistry. Aust Dent J. 2020;65(2):131–142. doi: 10.1111/adj.12754.

- Ding XG, Li SW, Zheng XM, et al. The effect of platelet-rich plasma on cavernous nerve regeneration in a rat model. Asian J Androl. 2009;11(2):215–221. doi: 10.1038/aja.2008.37.

- Liao CH, Lee KH, Chung SD, et al. Intracavernous injection of platelet-rich plasma therapy enhances erectile function and decreases the mortality rate in Streptozotocin-Induced diabetic rats. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:3017.

- Huang YC, Wu CT, Chen MF, et al. Intracavernous injection of autologous platelet-rich plasma ameliorates Hyperlipidemia-Associated erectile dysfunction in a rat model. Sex Med. 2021;9(2):100317–100317. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2020.100317.

- Wu CC, Wu YN, Ho HO, et al. The neuroprotective effect of platelet-rich plasma on erectile function in bilateral cavernous nerve injury rat model. J Sex Med. 2012;9(11):2838–2848. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02881.x.

- Wu YN, Liao CH, Chen KC, et al. CXCL5 cytokine is a major factor in platelet-rich plasma’s preservation of erectile function in rats after bilateral cavernous nerve injury. J Sex Med. 2021;18:698–710.

- Wu YN, Liao CH, Chen KC, et al. Dual effect of chitosan activated platelet rich plasma (cPRP) improved erectile function after cavernous nerve injury. J Formos Med Assoc. 2022;121(1 Pt 1):14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2021.01.019.

- Israeli JM, Lokeshwar SD, Efimenko IV, et al. The potential of platelet-rich plasma injections and stem cell therapy for penile rejuvenation. Int J Impot Res. 2022;34(4):375–382. doi: 10.1038/s41443-021-00482-z.

- Everts PA, Devilee RJJ, Brown Mahoney C, et al. Exogenous application of platelet-leukocyte gel during open subacromial decompression contributes to improved patient outcome. A prospective randomized double-blind study. Eur Surg Res. 2008;40(2):203–210. doi: 10.1159/000110862.

- Mohammadi S, Nasiri S, Mohammadi MH, et al. Evaluation of platelet-rich plasma gel potential in acceleration of wound healing duration in patients underwent pilonidal sinus surgery: a randomized controlled parallel clinical trial. Transfus Apher Sci. 2017;56:226–232.

- Lin MT, Wei KC, Wu CH. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma injection in rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10(4):189. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10040189.

- Wong SM, Chiang BJ, Chen HC, et al. A short term follow up for intracavernosal injection of platelet rich plasma for the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Urol Sci. 2021;32(4):171–176. doi: 10.4103/UROS.UROS_22_21.

- Schirmann A, Boutin E, Faix A, et al. Pilot study of intra-cavernous injections of platelet-rich plasma (P-shot®) in the treatment of vascular erectile dysfunction. Prog Urol. 2022;32(16):1440–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.purol.2022.05.002.

- Sharun K, Pawde AM. Amarpal, null. Classification and coding systems for platelet-rich plasma (PRP): a peek into the history. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2021;21:121–123.

- Rossi LA, Murray IR, Chu CR, et al. Classification systems for platelet-rich plasma. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B(8):891–896. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.101B8.BJJ-2019-0037.R1.