What Is Europe?

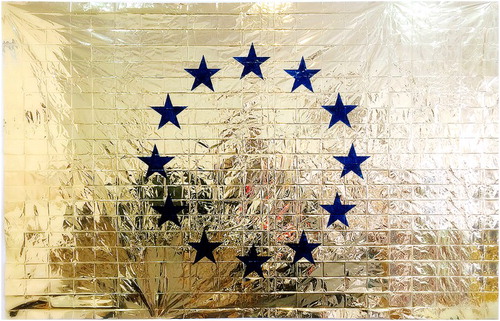

At a time when the Schengen Agreement is being reconsidered and the refugee crisis is reconfiguring Europe and its borders, the question that seems most pressing is, what is Europe? The re-elaborations of the European flag above suggest different answers.Footnote1 As one of the many contested frontiers of Europe, Southern Italy constitutes a significant starting point and internal site for interrogating the postcoloniality of Europe. The work of Calabrian artist Demetrio Giuffrè, ‘Stelle cadenti’, not only questions the internal cohesion of the European Union, it also implicitly interrogates what it means to look at Europe from Southern Italy, which has historically embodied internal subalternity (). Giuffrè’s work solicits a reflection on the extent to which a sense of belonging to Europe is feasible for Italian Southerners, whose national identity has constantly been and continues to be questioned.Footnote2 Another compelling example of a contested view of today’s Europe is Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen’s “Inverted Flag” (). The inversion in the colours of the flag—blue stars on a golden background—shows the reverse side of today’s Europe. If the European Union was founded with the idea of demolishing barriers and promoting free circulation within Europe, this purpose has been achieved through the erection and reinforcement of barriers around Europe. The survival blanket on which the flag is painted, therefore, functions as a metaphor for the inadequacy of the European Union to deal with the refugee crisis and the massive arrival of migrants.Footnote3

Figure 1. Demetrio Giuffré, ‘Stelle cadenti’, 2010, 80 × 120 cm, Silicone and acrylic on canvas, courtesy of the artist.

These reinterpretations of the European flag denounce the inability of the founding states of the European Union to form a cohesive and coherent entity and suggest the idea that Europe is an unattainable and elusive promised land for migrants, asylum-seekers, and refugees who continue to die by the thousands every year trying to cross the Mediterranean and, more recently, the Aegean.Footnote4 Is Europe, then, like the circle of falling stars in Giuffrè’s ‘Stelle cadenti’ and the survival blanket in Larsen’s ‘Inverted Flag’, only a reverse ideal of unity, a failed attempt at uniting countries that cannot really hold together? Is it a fortress whose self-protective policies kill thousands of people every year?Footnote5

Figure 2. Nilolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen, ‘Inverted Flag’, 2016, 215 cm × 140 cm, oil paint on survival blanket, courtesy of the artist.

Transnational migrations and the refugee crisis have dominated the discourse on Europe in the middle of an economic recession and the rise of international terrorism. Between 2010 and 2015, countries such as Italy, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Greece have been at risk of financial default and of exiting the European Union. The Paris terrorist attacks—first on the offices of the satirical weekly newspaper Charlie Hebdo on 7 January 2015 and subsequently on the Bataclan Theatre, the soccer stadium, and a number of cafés and restaurants on 13 November 2015—as well as the attacks on the Zaventem Airport and the Maelbeek metro station in Brussels on 22 March 2016, have brought to international attention the fact that terrorism is perpetrated mainly by European citizens, including second-generation Europeans.Footnote6 This in turn has brought the discussion back to issues of radicalization, hate, and lack of social integration. The Syrian refugee crisis, which escalated in the summer of 2015, combined with the continuing arrival of new migrants through southern Europe, has once again brought to the fore the purported urgency of defending borders against the ‘invasion’ of non-white, non-Christian subjects. Numerous barriers and walls have been erected as a consequence, but this strategy, as Wendy Brown has pointed out, is more often the staging of the failure on the part of a sovereign state to defend its borders than it is a real reinforcement of them.Footnote7

A Fractured Europe

In the immediate aftermath of the terrorist attacks, as spontaneous, civil mobilizations against terrorism mounted, it became increasingly clear that the very spatial organization of Europe’s cultural values and political borders was at stake. Europeans rallied, in the name of their shared values, against a common, internal enemy. In light of these latest events, how does a postcolonial approach to Europe illuminate the politics of European identity, at a moment when the European Union is confronted with increasing border wars, the physical and social exclusion of migrants, the exploitation of undocumented migrant workers (many from the former overseas colonies of the ex-empires), strong anti-immigration and anti-Muslim feelings, and the consolidation of the racist extreme right? In this special issue, we approach today’s Europe from different national perspectives and we suggest that one of its unifying factors is indeed its shared postcoloniality. The underlining question of the volume is whether the postcolonial condition of different European countries determines the postcolonial nature of today’s Europe as a whole. In answering this question, we identify the salient traits that contribute to shaping national and European postcolonialities in a shared colonial history and memory; in the dynamics and clashes of contemporary transnational immigrations; in the ways in which processes of ‘otherization’ are enacted through old and new forms of racism; in the political and cultural practices by postcolonial subjects, which are shaping different national cultures and creating common trajectories across Europe.

This special issue brings together the interventions of a number of scholars from different European countries (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, and Denmark) where postcolonial theory has been produced outside the ‘mainstream’ of postcolonial studies—geopolitically represented by Great Britain, France, and, to a certain extent, the Netherlands. The collection thus scrutinizes how ‘peripheral’ perspectives on the postcolonial reshape and revitalize the postcolonial paradigm as a whole. By this we do not mean to suggest that the colonial histories of Great Britain, France, and the Netherlands are the same or that they have produced the same effects. Nor do we imply that all the countries we include in this special issue are postcolonial in the same way, or that they adopt the same paradigm of postcoloniality; quite the opposite, in fact. Our methodology aims at identifying lines of continuity among different national cases that may help define a European postcoloniality, while simultaneously tracing lines of discontinuity that may bring to focus the specific postcoloniality of the national cases under consideration. With this intent in mind, each essay included in Postcolonial Europe presents the colonial history of one national case, while also examining how other specific historical events and social phenomena, at a European level, have historically contributed to the shaping of that country’s national identity. Many of the contributors in the volume also explore issues of colonial memory and legacy, tracing trajectories among different postcolonialities in the present, mainly interrogating issues of subalternity, dynamics of empires within and without Europe, processes of racialization, and the impact in today’s European societies of transnational immigrants, many (but not all) of whom are descendants of ex-colonial subjects.

The articles gathered in this special issue point to models of postcoloniality that are alternative—and complementary—to the British one. More specifically, they show how the dichotomy hegemonic/subaltern does not quite represent all postcolonial imperial histories. In ‘Between Prospero and Caliban: Colonialism, Postcolonialism, and Inter-Identity’, Boaventura De Sousa Santos criticizes the lack of comparative perspective that has pervaded postcolonial studies, which traditionally has considered the relationship of the British empire with all its colonies as homogeneous, and at the same time has disregarded the many differences existing between British and other colonialisms.Footnote8 Analysing how the British paradigm cannot be applied to the Portuguese context, Santos argues that the semiperipheral position Portugal has occupied in capitalist modernity since the seventeenth century has produced a semiperipheral colonialism and postcoloniality, as well as a semiperipheral position within the European Union. Locating Portugal on the fringe of modernity, Santos argues that the outcome of this marginality was a colonialism not quite hegemonic. It was colonialism nonetheless, but of a ‘subaltern’ kind.Footnote9 Since the position Portugal occupies shifts whether it is considered in relation to the colonized territories (hegemonic position) or to major colonial empires such as the British (subaltern position), a binary system based on the dichotomies colonizer/colonized and self/other is insufficient to represent Portugal, its colonial history, and its postcolonial contemporaneity. Processes of ‘otherization’ enacted in and by minor colonial empires—such as Portugal—are even less linear or binary than others. If the colonized was ‘the Other’ of the colonizer, the Portuguese colonizer in turn was otherized by major empires. This process produced a lesser sense of otherization in the colonized of minor empires and not quite the same sense of hegemony in the colonizer. Such theoretical framework can be applied—mutatis mutandis—to other minor colonial cultures included in this collection and to their postcolonialities. The notion of subalternity not only shifts in time, but it changes as a result of migrations because it intersects categories of race, class, religion, and citizenship. Migratory flows reposition and redefine subjectivity in national and intra-national contexts in today’s Europe.

As the array of chapters gathered in this special issue demonstrates, Europe as a political expression has been historically fractured within and without its nation-states. Its history is interspersed with cases of internal colonialism and intra-national or intra-regional colonial relations (as in the case of Ireland, Italy, and Denmark), as well as political and economic rivalry for expansion in overseas territories (as in the case of Portugal’s global empire). Moreover, two of the countries included here—Ireland and Switzerland—never established sovereignty in extra-national territories. Lines of continuity are nonetheless traceable among some of the national cases under consideration. Italy and Germany, for instance, share a relatively short colonial history; they both lost their colonies as a result of political treaties rather than decolonization movements. This particular combination of events has in turn made possible the creation and transmission of the myth of the good colonizer and the disavowal of responsibility in the postcolonial period. Ireland was not a colonizing but a colonized country, in spite of its being part of Europe, and Denmark had colonies within as well as without Europe. Switzerland, on the other hand, never had a colonial history. These particularisms of colonial relationships within Europe require a broadening of the very notion of colonialism and, consequently, of postcoloniality.

Lines of continuity also emerge in the economic and political subordination of Southern European countries (Greece, Spain, Portugal, Italy) in relation to the ‘strongest’ nations within the European Union. Such connecting links combine with the disjunctive elements present in different European postcolonialities. In the 1960s and 1970s, when England, France, and the Netherlands were receiving high numbers of economic immigrants from their former colonies, Southern Europeans—that is, citizens of ‘minor’ countries within the EU such as Portugal, Italy, Spain, and Greece—were settling as guest workers in France, Belgium, Switzerland, and Germany.Footnote10 Their social and economic subalternity within those European nations structured the relationship of power within these countries in ways that are better understood from a postcolonial perspective. However, today Southern European countries do not necessarily share all salient aspects of their contemporary postcolonial condition. Since the 1980s, as a consequence of being integrated more fully into the European Union, Portugal, Spain and Italy have all become countries of immigration without ceasing to be emigrant nations. Yet, unlike Italy, Spain’s immigrants are predominantly from its former colonies (Morocco, Equatorial Guinea, Spanish-speaking Latin America). Differently from the Spanish and Italian contexts, Muslim populations are not a significant factor of Portugal’s contemporary immigrations. Like Italy, Portugal has been recently receiving migrants from Eastern Europe, South East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and China—yet, like Spain, the majority of immigrants are from the former colonies, namely Brazil, Cape Verde, and Angola. Most interestingly, Portugal has also seen a significant wave of return migrations to Brazil and Angola, as Portugal is experiencing an economic recession. Despite this fragmentation, European postcolonial countries share, if not a common history of colonial expansion, a shared imperial history reinforced by sedimented myths, images, discourses, and cultural practices. The case of Switzerland—a nation-state without colonies and thus allegedly immune from racism and discriminatory practices—aptly illustrates how the historical formation of a sense of Europeanness from the late nineteenth century onward relied, among other things, on a shared European colonial and modern consciousness. A diffuse colonial imaginary—disseminated transnationally through commodity culture, household products, and positivist theories—produced a series of implicit notions of ‘blackness’ and ‘Africanness’ and, by contrast, established and stabilized a European male, middle-class, and white sense of selfhood, steeped in privilege, sophistication, and modernity, what Noémi Michel defines as ‘the white subject of the European imperial space’ (see Michel in this volume).

History and Memory in the Post-empires

Commenting on Europe’s colonial crimes, Paul Gilroy has recently argued that ‘comparable instances of conflict over colonial history, social memory and national identity have lately been evident in many locations both inside and beyond Europe’s battlements’.Footnote11 Conflicts and negotiations over the colonial past reveal that Europe has often conceived of itself as having multiple and fractioned identities. As Etienne Balibar argues,

In all its points, Europe is multiple; it is always home to tensions between numerous religious, cultural, linguistic, and political affiliations, numerous readings of history, numerous modes of relations with the rest of the world, whether it is Americanism or Orientalism, the possessive individualism of ‘Nordic’ legal systems or the ‘tribalism’ of Mediterranean familial traditions.Footnote12

Such identities have been a reflection of uneven relations of power within Europe as well as within its imperial territories, despite the claim of universalism and cultural cosmopolitanism that imperialism has put forward as its overarching mission.Footnote13 Imperialist politics imposed cultural imperialism—colonized subjects were incorporated through cultural assimilation—yet today postcolonial citizens are differentially included on the basis of a conception of European citizenship predicated on difference. While European citizenship transcends national borders, ‘most postcolonials continue to live as citizens within nation-states’ and are only ‘conditionally citizens of nation-states’.Footnote14 This is part of the legacy of European colonial history, which rearticulates today the dichotomy colonizer/colonized by reproducing the distinction between citizens and illegal immigrants. Processes of otherization and differential citizenship reproduce in contemporary Europe systems of power implemented and enforced in colonial times.

The colonial legacy permeates today’s societies in most of the national cases included in the issue. Belgium has a very ambivalent attitude towards its colonial history in the Congo, a territory brutally exploited by King Leopold II and administered as his private domain before it became an official colony of Belgium. This ambivalence is also instrumental in resisting Flemish nationalist opposition to the Belgian crown. In the case of Portugal, the dichotomy of hegemonic/subaltern generally associated with colonizer/colonized—which, as stated before in Boaventura De Sousa Santos’s words, does not accurately represent Portugal’s colonial history—has been reversed in contemporary times. Portugal, whose inclusion in the European Union has often been questioned, has been surpassed by its main colony, Brazil, which now occupies a much more central position than the former colonizer in a global context, both at an economic and at a cultural level. Finally Switzerland, the only country in this collection that is not part of the European Union, has recently been conceptualized as a postcolonial country in spite of the fact that it never had a colonial history.Footnote15 This is part of a larger theoretical trajectory that considers ‘colonialism without colonies’ as an imperialistic system in which countries such as Switzerland, Sweden, and Iceland ‘had an explicit self-understanding as being outside the realm of colonialism, but nevertheless engaged in the colonial project in a variety of ways and benefitted from these interactions’.Footnote16

If the centrality of the British paradigm is historically determined, part of this centrality is also dependent on the language in which the postcolonial discourse is produced and articulated.Footnote17 Including minor empires and their languages in the debate on colonialism and postcolonialism means decentring British cultural and linguistic imperialism in the field of postcolonial studies and beyond. Although English is the language in this collection, scholarship in a number of other languages is at the base of the essays included. This brings to the fore not only new perspectives and articulations, but also new structures of thought, epistemological genealogies, and critical formulations. The question of language does not only affect the production of theory, but also the circulation of cultural production in languages other than English, which generally remains very much on the outskirts of the ‘postcolonial cultural industry’.Footnote18 To this aim, some of the essays in this collection—specifically the ones on Portugal, Italy, and Denmark—include an analysis of the literary, artistic, and cinematic production in the national languages of these countries, which generally remains invisible in postcolonial analyses at large.

Alongside the question of language, the way in which the past is continually reconstructed has been another major concern in the field of postcolonial studies.Footnote19 A postcolonial approach to Europe entails a constant vigilance towards the past, which means exercising a comparative perspective in the analysis of diverse historical phenomena. However, postcolonial studies has not until recently been attentive to a comparative historical approach to empires.Footnote20 This is particularly true for the ‘minor’ empires—such as the Italian, the German, the Belgian, and the Danish ones—included in this volume. In considering the state of the art of the field of postcolonial history, Graham Huggan urges postcolonial scholars to undertake further historical comparative studies that would take seriously the fact that empires are plural, yet they are also global and interconnected.Footnote21 Moreover, postcolonial studies has also had a ‘paradoxical’ relation to cultural memory. While many of the foundational texts of postcolonial theory written in English have dedicated little space to the question of cultural memory, memory studies has avoided confronting the issue of colonialism and its legacy. In trying to fill this gap, in his critical overview of the role of cultural memory in postcolonial studies, Michael Rothberg reminds us how postcolonial temporality, rather than marking a violent break with the past, stands in a disjunctive relation to colonialism. By its insistence on providing a long view on the lingering presence of the colonial past into the present, postcolonial studies reveals the tenacity of colonial cultural memory and its persistence beyond former colonization and even in the absence of it.Footnote22 This is certainly the case with many of the countries included in this special issue.

Many of the contributors in this volume illustrate how, in postcolonial Europe, the re-elaboration of an imperial memory has not necessarily stemmed from deliberate and structured efforts through political initiatives. On the contrary, ‘systemic forms of forgetting’Footnote23 are at work in contemporary European political life, as well as in the daily life of Europeans. Europe’s unresolved relationship with its imperial past, which Paul Gilroy has defined in terms of a ‘melancholic cycle of guilty evasion, filtering, refusal and blockage’,Footnote24 is often mystified as unapologetic patriotism (as, for instance, in Switzerland and Belgium). The memory of colonialism is indeed contested. Such contestation shapes the perception and fruition of postcolonial memory politics and its attendant spaces, as different places are inhabited differently on the basis of one’s cultural memory. In Belgium, for instance, the lines of intra-national differentiation between the French- and Flemish-speaking populations fracture even further language divisions, urban and suburban spaces, racial existences, and cultural legacies. In contemporary Belgium, as Goodeeris argues in this volume, the colonial past speaks through monuments that function as political embodiments of colonialism’s current vitality. All in all, the limited number of Congolese people and the varied experiences of other Sub-Saharan migrants that constitute the African diaspora in Belgium do not succeed in occupying much space in its postcolonial memory. In Denmark, as Lars Jensen states in his contribution, contemporary disavowal of colonial responsibility is possible due to a lack of comparative perspective that has kept the analysis of Danish colonialism in the tropics and in the North Atlantic separate. This disjunction has produced narratives of benevolence and exceptionalism and overlooked the connections existing between the two colonial zones within a more general colonial paradigm. This disavowal of colonial responsibility in the present has translated into a lack of recognition of Danish neocolonial politics as such. These politics have been articulated through the direct exertion of power in the overseas autonomous territories in the North Atlantic, and through the involvement of Denmark in development projects in the tropical colonies that promote tourism—and colonial nostalgia—in ex-colonial territories such as the Virgin Islands and the Faroe Islands. Britta Schilling argues that Germany has never been affected by colonial amnesia and that the memory and legacy of colonialism have always been part of German history and culture. If, soon after decolonization, Germany created a narrative of a good colonialism and of an unjust expropriation that fostered nostalgia for the lost colonies, in postcolonial Germany the legacy of colonialism combines with the memory of the Holocaust, the experiences of Germans of African descent, and the presence of contemporary migrants. For Germany, the consolidation of its colonial memory is a process that reveals the complexity of its postcoloniality.

European Postcoloniality Against Racism

In many of the countries included in the volume, the act of facing the past is prompted by the presence of postcolonial subjects who are re-linking the often lost connections between different European colonialities. As a result, they create networks of cultural affiliations and shared solidarity, networks that transcend nationality and that are rooted in a common history of migration, cultural domination, subalternity, and racialization. In this regard, the case of Switzerland is a telling example of how European postcolonial voices are at most successful when they take the form of reverse-narratives that utilize the logic and signifying strategies of the state for their own ends. In this collection, Noémi Michel documents that the reactions by Swiss citizens and residents of African descent to a racist, right-wing political campaign was to incorporate the language of Swiss exceptionalism in order to subvert hegemonic conceptions of a racially homogeneous ‘Swissness’. Similarly, as Goddeeris indicates, the reactions against Belgium’s unflinching attachment to its colonial past have been most effective when they managed to connect their own particular claims to a larger political issue, thus enlarging their scope and rendering such claims familiar to the Belgian public opinion. In both countries, postcolonial activism has targeted racism as one of the most salient features of the colonial legacies, but the reactions in these two national cases have been different. Belgium has insisted on the alleged neutrality of its colonial memory, kept alive by the toponomastic and colonial monuments. Nonetheless, the unilateral themes of Belgian national monumentality (all of the colonial monuments are dedicated to white colonialists, missionaries, or King Leopold II, none to Patrick Lumumba or any other Congolese) attest to the country’s refusal to acknowledge the Congolese as agents within the postcolonial public space of remembrance. Yet Belgian citizens of Congolese descent, joined by Africa diasporic migrants, despite lack of political support, have mobilized around the issue of collective memory by identifying violence and racism as universal themes within Europe, rather than as Belgian particularities (see Goddeeris in this volume). Differently from Belgium, Switzerland has appealed to the exceptionalism of the Swiss context, characterized by the post-war internal balance between linguistic and religious differences and achieved in virtue of the institutionalization of federalism, neutrality, and direct democracy. In Switzerland, mobilization against right-wing racism by a multiparty coalition of candidates of African descent has taken the form of a visual performance that intended to name the unnameable, by explicitly and visibly referencing race and blackness (see Michel in this volume).

A postcolonial approach to the question of race within a European context points to the fact that Europe’s racial identity has not completed its process of social formation with the end of the age of empire, nor is it simply limited to the historical and geographical context of the European ex-colonies, and therefore to the spaces outside of Europe. As David Theo Golberg has argued, the formation of Europe’s modern states has been determined by racial terms and conditions, as race has been embedded within the European liberal social contract tradition, pervading the everyday material practices of modern political consciousness. Whiteness has shaped Europeans’ definition of the modern self, while the identification of Europeanness and whiteness has gradually turned into ‘a state of being, desiderable habits and customs, projected patterns of thinking and living, governance and self-governance’.Footnote25 Constantly altered, readapted and renegotiated, after the turn of the 19th century ‘whiteness became not a racial but a national identity’.Footnote26 Goldberg aptly takes the Royal Belgian Museum for Central Africa—established by Leopold II in the wake of the successful International Exposition he sponsored in 1887—as an example of that ‘racial manifacture’ materialized in the ‘spectacle of racial contrast of Europeanness and Africanity’.Footnote27 Such contrast presided over the consolidation and maintenance of whiteness in terms of a European racial homogeneity. Today, in the face of the increasing heterogeneity of European societies, race has (at least) a twofold dimension. On the one hand, the European identity is, subtly and not so subtly, invoked in terms of racial homogeneity and identification with whiteness. Race is implicitly or explicitly implicated in what it means to be European, as immigration, and the increasing demographic diversity of European countries, constitutes a tangible threat to the sense of their homogeneity. On the other hand, there exists a new transnational, diasporic configuration that transcends the direct relationship of identification between the colonial periphery and the centre and contributes to a shared black European condition. Participation in the civil and cultural life of Europe is what constitutes belonging for all new Europeans, not the abstract belonging to the territory of the nation-state.

The participation in a pan-European postcolonial citizenship is most evident in the way postcolonial subjects are presently creating a cosmopolitan community identified by a shared sense of blackness. In a country such as Switzerland which, together with Ireland and yet differently from it, has been included in this special issue as an example of postcoloniality in the absence of former colonies, racism takes the explicit form of a discourse centred around the process of racialization, rather than racism tout court. Indeed, the example of the black sheep poster created by the right-wing Swiss People’s Party (SVP) illustrates Goldberg’s insightful formula of ‘the racial Europeanization’ by which, in today’s Europe, race is a muted sociality, ‘silenced but assumed, always already returned and haunting’.Footnote28 Yet it also exemplifies what happens in the attempt at counteracting racism in the absence of a racist colonial past. As Michel argues, the political activism born in reaction to the sheep poster reframed racism by making race visible and internal to the political and subjective life of contemporary Switzerland. Its defenders, instead, activated rhetorical devises that make race ‘evaporate’Footnote29 by reverting to the universal concept of a raceless foreignness so much engrained within Swiss collective imaginary. Most tellingly, the image of the sheep, as an object of political encoding of hegemonic discourses, embodies a commodified form (the sheep transformed into a poster) that puts back into circulation a colonial commodity system on which European imperial culture has long thrived. In Italy, the question of the racial identity of the country, historically constructed as white, Catholic, and Mediterranean, takes centre stage in the cultural memory and production of postcolonial Italian artists and writers who are replying to the unwillingness of Italian institutions to consider the intersection of blackness, ‘Muslimness’ and Italianness as desirable or even possible. In postcolonial Italy, black bodies are hardly positioned—both materially and symbolically—within the national space. To this state of affairs, writers and activists of African descent are responding by questioning the very principle on which Italianness is constituted both in the conception of citizenship and in everyday practices. Notably, Southern Italian artists, activists, and scholars are also contributing to the debates on Europe’s border wars with a reverse discourse that reclaims ‘Southerness’ and its specific counter-hegemonic affective relations as a response to the perceived attempt at European Northern hegemony (see Lombardi-Diop and Romeo in this volume). Portugal’s stratified imperial history weighs on the country’s contemporary ‘intercultural model’, understood in terms of an identity of ‘fusion’ and ‘hybridity’ that differentiates Portugal’s postcolonial model from British ‘multiculturalism’ and French ‘Republican assimilationism’. As Arenas convincingly argues in this volume, such myth of cultural exceptionalism, often referred to as ‘Lusotropicalism’, tends nonetheless to downplay and render invisible the presence of multiple generations of citizens of African descent, pigeonholed into the categories of ‘blacks’ or ‘Africans’, and therefore ‘othered’ by the majority of the white Portuguese population. Notwithstanding this predicament, the city of Lisbon, inflected with a black diasporic sensibility, represents today an important source of cultural capital as many Portuguese of African descent have established there a global Afro-diasporic urban culture through urban commercial sites and venues, and a thriving musical scene. Germany has developed a discourse on both historical racism in the past and on processes of racialization in the present (see Schilling in this volume). ‘Continuationists’ in Germany read the extermination of the Herero in Namibia and the enacting of state racism in the colonies as a prelude to National Socialism’s politics. In present time, voices of African Germans (descendants of Africans who have been in the countries for many decades, mostly since colonial times and World War II), have spoken both inside the academia and in extra-academic organizations and networks, contributing to the shaping of a German Black identity in a country so strongly characterized by a history of white supremacy and superiority. The voices of Black Germans also intersect those of contemporary migrants and second generations of African descent and their desire to keep a sense of continuity with the past, while at the same time constructing a German identity in the present. In Ireland, a country of mass emigration whose population abroad has been strongly racialized and whose whiteness in British imperial discourse was always questioned, has applied very restrictive policies when it comes to attributing citizenship to people of non-Irish descent, while the belonging to the Irish Republic is predicated upon racial difference (see Laird in this volume).

Volume Presentation

Fernando Arenas’ chapter on postcolonial Portugal opens this special issue, offering a conceptual map of Portuguese postcoloniality by taking into account the stratified history of bi-directional migrant movements within the Lusophone world and the rise of an Afro-Portuguese culture, a phenomenon that highlights the centrality of African immigration in the life of contemporary Portuguese society. The particularity of postcolonial Portugal is the stratified history, starting from the 1960s, of different waves of immigration from the African colonies, including repatriations of Portuguese settlers and their children, the so-called Luso-Africans or Afro-Portuguese. In reclaiming the centrality of African culture for contemporary Portugal, Arenas investigates the vibrant urban scene of African Lisbon, concentrating on the work of world-renowned film director Pedro Costa, whose ‘empathetic gaze’ and cinematic poetic of ‘distant proximity’ produce a combination of spatial disorientation while simultaneously establishing a complicit pact with the audience in relationship to the integrity of the ‘other’—mostly marginalized black women and men—represented on screen.

Starting from the consideration that Italian cultural roots and national identity are currently shifting as the result of contemporary transnational migrations and globalization, in Chapter Two Cristina Lombardi-Diop and Caterina Romeo analyse how the paradigm emerging from the Italian national case contributes to a redefinition of the postcolonial canon centred on British history and culture and to the notion of a ‘European’ postcolonial as a whole. To this aim, the authors identify in colonial history and contemporary immigration the threads that connect the postcoloniality of Italy to that of other European countries. At the same time, they locate the specificity of the Italian postcolonial in the intersection between these factors and other events in Italian history that have strongly influenced the process of shaping an Italian national identity: the Southern question, intra-national and international mass emigrations, new mobilities, the subaltern position of Italy within the European Union, and the geopolitical dislocation of Italy as one of the Southern frontiers of Europe. The authors close their essay by presenting a Mediterranean Southern perspective grounded in new forms of knowledge and aesthetic sensibilities that counteract Europe’s sense of encroaching and its politics of border protection.

Ireland occupies a unique position in this collection, as it features as a colonized rather than a colonizing country. In Chapter Three, Heather Laird reconstructs how, over the past 35 years, prominent Irish scholars have read the history of their country as characterized by imperialism and anti-colonial nationalism, conceptualizing the country as a former British colony to all effects. If the geographical position of Ireland as an intra-European country and the inclusion of European white Christian population in the ranks of the formerly colonized have been the main arguments put forward by detractors of Irish postcolonial studies, these factors have been adopted by former ‘Second World’ countries—especially Poland—whose postcolonial condition has been predicated on its relationship with Russia/the Soviet Union and with Western Europe. This broadening of the postcolonial paradigm, Laird argues, raises important questions in the European context regarding what countries can and cannot be deemed as postcolonial and on what basis.

Chapter Four, by Idesbald Goddeeris, explores the contested status of postcolonial public spaces and monuments as Belgium—and, more specifically, postcolonial Flanders—negotiates its inability to engage in a meaningful and long-lasting re-elaboration of its colonial past. The article focuses on a number of significant public controversies of the very recent past in which the political establishment and public opinion, and in particular individuals and collective bodies comprising migrants and second-generation Belgian citizens of Congolese origin, have been most divided. The author convincingly demonstrates that a number of attempts to publicly address the crimes of Belgian colonialism and bring the political forces of the country to take a stance in the face of its enduring colonial legacy have been met with a persistent resistance. Goddeeris’ painstaking analysis of debates surrounding the status of street names, monuments, and public places, none of which yet dedicated to a Congolese, illuminates the ‘Belgian particularity’ of the country’s postcoloniality, that is, its persistent affirmation of a one-sided view of colonial history that continues to fracture its present civic life.

In her analysis of Swiss postcoloniality included in Chapter Five, Noémi Michel applies the recent theoretical findings by David Theo Goldberg and Fatima El-Tayeb on raceless racism to Switzerland and, more specifically, to the debate on the 2007 sheep campaign issued by the far right-wing SVP. The sheep campaign represents one of the most controversial political debates on racism, ‘difference’, and inclusiveness in today’s Europe. The SVP poster depicts white sheep drawn in a cartoonish and simplistic style—differentiated by means of a white/black chromatic contrast—kicking a black sheep out of a territory designated by the Swiss national flag. As a country without colonies, Michel reminds us, Switzerland was nonetheless enmeshed in a transnational web of markets during the age of empire. The poster image, accompanied by the slogan ‘For More Security’, was reminiscent of the style of advertisement used to publicize colonial commodities in the increasingly globalized markets of imperial Europe. In analysing the mobilization of different political actors against or in defence of the sheep poster, Michel aptly demonstrates that the sheep campaign controversy consisted of a struggle between three antagonistic positions: an antiracist discourse, an anti-exclusionary discourse, and a defensive discourse, all of which were more or less complicit with the logic of raceless racism.

In Chapter Six, Britta Schilling interrogates the term ‘postcolonial’ and analyses the ‘four dimensions’ in which it is articulated when related to the history of Germany, the first European country to decolonize in 1919. Determined to anchor German postcolonialism to the country’s earlier history—rather than to cultural and social processes of globalization and contemporary transnational immigration—Schilling includes in the multiple dimensions of German postcolonialism colonial nostalgia and colonial memories of white Germans, the intersection with the paradigm of the Holocaust, and the narrations and experiences of Black Germans. Starting from Adorno’s admonishment to Germans in 1959 on the necessity to come to terms with their National Socialist past, Schilling identifies the common ground of German and other European postcolonialisms not in transnational migrations and processes of racialization and racism (which, in her view, constitute only a marginal dimension), but rather in the necessity of different European countries and Europe as a whole to work through their colonial past and come to terms with it.

In Chapter Seven, Lars Jensen presents another case of intra-European colonization. He draws connections between Danish colonialism—which extended from the Arctic Circle to the ‘tropics’ and was protracted in time—and a Nordic colonial history on the one hand, and on the other a more general European colonial history. Jensen laments the lack of a comparative perspective in the analysis of the two fronts of Danish colonization (the North Atlantic and the tropics). This is due mainly to the fact that, until recently, the Danish domination in the Arctic and Sub-Arctic region has not been defined as ‘colonial’; indeed, in the Danish national imaginary, this phenomenon has not been perceived as colonial expansion but rather as an extension of the nation-state. The fact that Danish colonialism in the tropics is now distant in time and that domination in the North Atlantic is not considered as real colonization has historically produced a process of disavowed responsibility. On the other hand, the disconnection from colonial history is coupled in contemporary times with a re-enforcement of different kinds of relations with former colonies. Jensen also observes how contemporary immigrations complicate the notion of national identity, and he explores the (post)colonial archive through an analysis of contemporary literary production.

The essays gathered in Postcolonial Europe contribute to re-defining Europe as a collective geopolitical space, highlighting the fact that Europe’s unity is found, most paradoxically, in the experience of its social and historical fractures. As the European nation-states are still expressing the long duration of their coloniality, Europe’s very borders are again being contested while the continent is most divided on its internal and external identity. In adopting a postcolonial lens and in linking national cases hardly considered in connection to one another, the volume identifies continuous lines in the very fractures produced by the colonial and imperial legacy, such as the controversies over a collectively agreed upon national identity; the contested re-elaboration of a colonial memory; the insistence on Europe’s racial and religious homogeneity in the face of its increased heterogeneity; the divisive and violent processes of otherization and racism and the political and cultural forms of resistance against their lethal effects; the past and current forms of intra-European colonization. Moreover, the essays indicate that a contested and reactive postcolonial Europeanness is to be found most strongly at the geographical and socio-economic peripheries of Europe, rather than at its centre. Hence, the volume contributes to provincializing and decentralizing not only Europe as a unitary, geopolitical entity, but also postcolonial studies as such. In the face of the tragic deaths at the hands of both terrorist extremisms and repressive border politics, a postcolonial approach to the continent points to one of the possible ways by which to examine Europe’s deep-seated fractures in order to begin the work of acknowledging and contesting its divisive unity.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jenna Severson, the Assistant Editor of this special issue, for her invaluable help in organizing the work and her assistance in the editing process. A warm thank to the blind reviewers for their generous work and to Demetrio Giuffrè and Nikolaj Larsen for granting us permission to reproduce their work.

Although the authors conceived and developed this essay together and wrote the section titled ‘Volume Presentation’ jointly, Caterina Romeo wrote the sections titled ‘What is Europe?’ and ‘A Fractured Europe’, while Cristina Lombardi-Diop wrote the sections titled ‘History and Memory in the Post-Empires’ and ‘European Postcoloniality against Racism’.

Notes on editors

Cristina Lombardi-Diop is Director of the Rome Studies Program at Loyola University Chicago, where she holds a joint appointment in Modern Languages and Literatures and Women’s Studies and Gender Studies. She is the editor and translator of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Moving the Center, recipient of the 2001 Nonino Prize. She is also the editor, with Caterina Romeo, of Postcolonial Italy: Challenging National Homogeneity (Palgrave 2012, published in Italian as L’Italia postcoloniale by Le Monnier-Mondadori in 2014) and the author, with Gaia Giuliani, of Bianco e nero. Storia dell’identità razziale degli italiani (Le Monnier-Mondadori 2013, Winner of the 2014 Prize of the American Association for Italian Studies). Her essays on white femininity, Fascism, and colonialism, Mediterranean migrations, and African Italian diasporic literature, have appeared in a variety of edited volumes and journals. Most recently, she has published on the need for a postcolonial and race theory approach to Italian American Studies, and on the visual grammar of Fascist colonial comics strips.

Caterina Romeo is Assistant Professor of Literary Theory and Gender Studies at the University of Rome ‘Sapienza’. She is the author of Narrative tra due sponde: Memoir di italiane d’America (2005) and the coeditor (with Cristina Lombardi-Diop) of Postcolonial Italy: Challenging National Homogeneity (Palgrave Macmillan 2012) and L’Italia postcoloniale (Le Monnier-Mondadori 2014). She has co-edited a double monographic issue of Dialectical Anthropology on contemporary migrations in Europe and a monographic issue of tutteStorie on Italian American women. She has translated into Italian the work of numerous Italian American women writers, among them prize-winning Louise DeSalvo’s Vertigo (Vertigo 2006, Special Acerbi Prize for Women’s Writing in 2008) and Kym Ragusa’s The Skin between Us (La pelle che ci separa 2008, John Fante Prize in 2009). Her essays on Italian American literature and culture, Italian postcolonial literature, postcolonial feminism, and constructions and representations of blackness in contemporary Italy have been published in international journals and edited volumes. She is currently completing a book-length manuscript on postcolonial literature in contemporary Italy.

Notes

1 Other re-elaborations of the European flag include the work of Italian street artist Blu, who painted a mural in 2011 near the surveilled border fences that separate Morocco from the Spanish city of Melilla (in Morocco). In the mural, the circle of stars in the European flag is made of barbed wire, which prevents the masses of people pressing at the border from entering the circle and, by extension, Europe (see http://www.blublu.org/sito/walls/2012/big/001.jpg, accessed 20 March 2016). See also the image on the Twitter account of the Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado (CEAR), employed to launch the petition #UErfanos, in which the blue background of the European flag is represented by the Mediterranean, while the 12 stars are replaced by the corpses of people who drowned at sea. See http://uerfanos.org/ (accessed 30 March 2016).

2 As it has often been argued, the solidity of the Italian position in Europe depends on Italy’s capacity to reduce the difference between its North and South. See Mario B. Mignone, Italy Today: Facing the Challenges of the New Millennium (Revised Edition), New York: Peter Lang, 2008. See also Lombardi-Diop and Romeo in this collection.

3 The theme of death in the Mediterranean as the result of migrants' attempt to access Fortress Europe from its Southern Frontier is the main theme in Danish artist Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen’s artistic work. See in particular ‘Ode to the Perished’ (2011) and ‘End of Dreams’ (2015), and in general his entire production on his website http://www.nbsl.info/ (accessed 30 March 2016). As we have argued elsewhere, Larsen’s aim in his work—similarly to our aim in our work on the postcolonial—is to keep alive the memory of those who perish trying to cross the Mediterranean. See Cristina Lombardi-Diop and Caterina Romeo, ‘Oltre l’Italia. Riflessioni sul presente e il futuro del postcoloniale’, From the European South—A Transdisciplinary Journal of Postcolonial Humanities 1, 2016, forthcoming.

4 The responsibility of the European Union in the drowning of so many people trying to access Europe has been at the centre of major representations by other European artists. In addition to the work of Nikolaj Bendix Skyum Larsen, see, among others, British sculptor Jason deCaires Taylor’s ‘The Raft of Lampedusa’, intended, as the artist himself wrote, not ‘as a tribute or memorial to the many lives lost but as a stark reminder of the collective responsibility of our now global community’ (posted on 4 February 2016 on deCaires Taylor’s Facebook page, available at: https://www.facebook.com/150479558321853/photos/a.693596164010187.1073741858.150479558321853/693597400676730/?type=3&permPage=1 (accessed 20 March 2016). See also Italian director Gianfranco Rosi’s Fuocoammare (Fire at Sea), a docufilm on people’s lives in Lampedusa and the landing of migrants from Africa on the island, which was awarded the Golden Bear at the Berlinale (Berlin Film Festival) on 21 February 2016. In an interview released after winning the prestigious prize, the director suggested to award the Nobel Peace Prize to the people of Lampedusa and Lesbos (Greece), for their invaluable humanitarian contribution in saving migrants' lives. See http://www.repubblica.it/spettacoli/cinema/2016/02/22/news/rosi_date_il_nobel_ai_pescatori_della_mia_lampedusa_-133944490/ (accessed 20 March 2016). For a discussion of Southern Italian artists' work on the Mediterranean crossings, see Lombardi-Diop and Romeo in this issue.

5 That migrations have been treated by the European Union increasingly as a matter of European security is also underlined, according to Lorenzo Rinelli, by the transition from Operation Mare Nostrum to Operation Triton in the Sicilian Channel. This transition has also had important repercussions on the lives of the Lampedusans. See Lorenzo Rinelli, ‘Translating Erratic Struggles: Reflections on Political Agency and Irregularity in Lampedusa’, in Luciano Baracco (ed.), Cultural Studies—Reimagining Europe’s Borderlands: The Social and Cultural Impact of Undocumented Migrants on Lampedusa, special issue of Italian Studies 70(4), 2015, pp 487–505. For a cinematic representation of Lampedusa and the ambivalent position the island occupies as a land of dreams for migrants and the internal other vis-à-vis the rest of the peninsula (and Sicily), see Ethiopian Italian film director Dagmawi Yimer’s Soltanto il mare (Only the Sea), 2011.

6 See, among others, “Paris Attacks: Who Were the Attackers”, BBC News, 2016. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34832512 (accessed 18 March 2016).

7 See Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty, New York: Zone Books, 2010.

8 Boaventura de Sousa Santos, ‘Between Prospero and Caliban: Colonialism, Postcolonialism, and Inter-Identity’, in Luzo-Brazilian Review 39(2), 2002, pp 9–43.

9 Santos, ‘Between Prospero and Caliban’, p 9.

10 While Stephen Castles and Mark Miller’s seminal work on global migrations offers a considerable amount of data, a consistent body of recent scholarship has included this particular case of intra-European migrations within larger studies on postcolonial migrations. See Stephen Castles and Mark J. Miller (eds), The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World, New York: Palgrave, 1998; Andrea L. Smith, Europe’s Invisible Migrants, Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2003; Ulbe Bosma, Jan Lucassen, and Gert Oostindie, Postcolonial Migrants and Identity Politics: Europe, Russia, Japan, and the United States in Comparison, New York: Berghahn Books, 2012.

11 Paul Gilroy, ‘Postcolonialism and Cosmopolitanism: Towards a Worldly Understanding of Fascism and Europe’s Colonial Crimes’, in Rosi Braidotti, Patrick Hanafin, and Bolette Blaagaard (eds), After Cosmopolitanism, New York: Routledge, 2013, pp 111–131.

12 Étienne Balibar, We, the People of Europe? Reflections on Transnational Citizenship, translated by James Swenson, Princeton, N.J. and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2004, p 5. For a detailed reconstruction of the political history of European citizenship, refer to Peo Hansen and Sandy Brian Hager (eds), The Politics of European Citizenship: Deeping Contradictions in Social Rights & Migration Policy, New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010.

13 Balibar 2004, pp 56–58.

14 Jean Comaroff, ‘The End of History, Again? Pursuing the Past in the Postcolony’, in Ania Loomba, Suvir Kaul, Matti Bunzl, Antoinette Burton, Jed Esty (eds), Postcolonial Studies and Beyond, Durham, N.C. and London: Duke University Press, 2005, pp 125–144, p 131, emphasis in the original.

15 See Patricia Purtschert, Barbara Lüthi, and Francesca Falk (eds), Postkoloniale Schweiz: Formen und Folgen eines Kolonialismus ohne Kolonien, Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2012. For an English version of the introduction to this volume, see Patricia Purtschert, Francesca Falk, and Barbara Lüthi, ‘Switzerland and “Colonialism Without Colonies”: Reflections on the Status of Colonial Outsiders', in Sandra Ponzanesi (ed), The Point of Europe: Postcolonial Entanglements, special issue of Interventions 18(2), 2016, pp 286–302. Available at: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1369801X.2015.1042395 (accessed 18 March 2016).

16 Barbara Lüthi, Francesca Falk, and Patricia Purtschert, ‘Colonialism Without Colonies: Examining Blank Spaces in Colonial Studies’, in Barbara Lüthi, Francesca Falk, and Patricia Purtschert (eds), Colonialism Without Colonies: Examining Blank Spaces in Colonial Studies, special issue of National Identities 18(1), 2015, pp 1–9, p 1.

17 See Sandra Ponzanesi, Paradoxes of Postcolonial Culture: Contemporary Women Writers of the Indian and Afro-Italian Diaspora, Albany: SUNY Press, 2004.

18 Cfr. Sandra Ponzanesi, The Postcolonial Cultural Industry: Icons, Markets, Mythologies, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

19 For a critical reading of postcolonial memory and the Charlie Hebdo events, see Cristine Quinan, ‘Hidden Memories: October 17, 1961, Charlie Hebdo, and Postcolonial Forgetting’, in Sandra Ponzanesi and Gianmaria Colpani (eds), Postcolonial Transitions in Europe: Contexts, Practices, and Politics, London and New York: Rowman & Littlefield International, 2016, pp 99–118.

20 One notable exception is Robert J.C. Young’s Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction, Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2001, a comparative historical analysis of postcolonialisms around the globe. For an historically informed European comparative perspective, see Prem Poddar, Rajeev Patke, and Lars Jensen (eds), A Historical Companion to Postcolonial Literatures: Continental Europe and Its Empires, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008.

21 Graham G. Huggan, ‘Introduction—Section One: The Imperial Past’, in Graham G. Huggan (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Postcolonial Studies, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp 28–37.

22 Michael Rothberg, ‘Remembering Back: Cultural Memory, Colonial Legacies, and Postcolonial Studies’, in Graham G. Huggan (ed), The Oxford Handbook of Postcolonial Studies, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp 359–379.

23 Gilroy 2013, p 112.

24 Gilroy 2013, p 116. Paul Gilroy has extensively re-elaborated the Freudian notion of melancholia in relation to Britain’s inability to come to terms with its imperial past in the second part of his After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture? London and New York: Routledge, 2004.

25 David Theo Goldberg, The Racial State, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2002, p 171.

26 Goldberg 2002, p 177.

27 Goldberg 2002, p 178.

28 David Theo Goldberg, The Threat of Race: Reflections on Racial Neo Liberalism, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2009, p 152.

29 Goldberg 2009, pp 151–160.