Abstract

Printed newspapers were widely read in the Dutch Republic since their emergence around 1618. Initially, the corantos were distrusted by the urban elite because of their low price and their broad appeal. As they gradually became a part of everyday life, their reputation as credible vehicles of domestic and (mostly) foreign news increased. This article examines why and how these newspapers were being read. It distinguishes four different reading habits as strategies for early modern readers of managing the continuous and often unreliable flow of news. The analysis combines surviving collections of printed newspapers with primary sources not usually employed for this purpose by scholars of early modern media, including images, private letters, diaries, and newspaper advertisements.

Introduction

Around 1675, the Haarlem artist Adriaen van Ostade made a drawing entitled ‘The Newspaper Reader’ (). Van Ostade, a pupil of Frans Hals, specialized in tavern scenes and depictions of the domestic surroundings of the lower middle classes. In this image too, of which only a nineteenth-century reproduction has survived, the setting is simple and homely. Two men in the foreground devote their attention to a printed newspaper, a single sheet that is easily identified as such through its idiosyncratic layout with two columns of congested paragraphs. The oldest of the two men has put on spectacles to read the densely printed bulletins. He is focused on the newspaper, but at the same time, he is still wearing his apron, indicating that he is merely taking a break from work. His younger companion appears to be listening attentively, although his jaded facial expression suggests that few of the bulletins can be qualified as breaking news. Reading the newspaper is presented as a social event, in which even the woman in the background may be participating as a secondary audience.

FIGURE 1 Adrian Schleich [after Adriaen van Ostade], Der Zeitungsleser (19th c. [1675]), Courtesy of RKD, The Hague.

![FIGURE 1 Adrian Schleich [after Adriaen van Ostade], Der Zeitungsleser (19th c. [1675]), Courtesy of RKD, The Hague.](/cms/asset/1b47c60f-c2d1-4222-b6f1-fc4ca0245fdd/cmeh_a_1229121_f0001_c.jpg)

With this print, Van Ostade captured an everyday activity of thousands of people in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic, but one that has been notoriously difficult for scholars to grasp. Historians of news have so far mostly emphasized the production and dissemination rather than the reception of information.Footnote1 Brendan Dooley, in a 2001 article provided an exception by concentrating on how news readers ‘experienced what they read’, but his interest ultimately lies more in the issue of credibility than in the practice of reading.Footnote2 The flourishing field of the history of reading has focused mainly on the reading of ‘Big Books’, using tools like handwritten marginalia which are extremely rare in ephemeral publications like newspapers.Footnote3 Private diaries have been used to good effect to examine individual reading habits ever since Kevin Sharpe explored the notes of one diligent reader. Recently, Kate Loveman wrote an intriguing study of Samuel Pepys’ news consumption through reading and collecting.Footnote4 Joad Raymond has focused on the (slightly different) genre of printed newsbooks, concluding that while some readers may have considered newsbooks mere vehicles of entertainment, others read them very thoroughly—judging from the few traces they left—often with very specific individual interests.Footnote5 If newspaper reading is addressed in more general works, like Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier’s History of Reading in the West, it is usually placed in the context of eighteenth-century social transformations that broadened the scope and appeal of mundane reading matter.Footnote6

For the Dutch Golden Age, there is some good recent scholarship which can serve as an historiographical vantage point. Hannie van Goinga’s extremely thorough study of the distribution of (and demand for) books and newspapers in eighteenth-century Holland, can be used as a reference, but its findings can be extrapolated to the seventeenth century only with considerable caution.Footnote7 Jeroen Blaak, in Literacy in Everyday Life, has devoted substantial attention to reading behavior in the Dutch Golden Age by examining two private diaries that contain multiple references to reading, and even, occasionally, the reading of news.Footnote8 His observations will be used here as the main point of departure. In what follows, I will attempt to do two things. First, I want to answer the basic questions about readership: Who read printed newspapers, why, and how? These questions may seem elementary, but it is important to emphasize that unlike for early modern England (or Germany), there is no proper study of newspaper consumption in Holland.Footnote9 This is all the more remarkable because in the United Provinces there was an unrivaled openness—a so-called ‘discussion culture’ in which printed newspapers could thrive.Footnote10 The present article, then, serves as a preliminary survey of a potentially very rich topic. Secondly, I examine the relative value of the eclectic array of sources historians can employ to enter this emerging field of research. After a short introduction on printed newspapers in the Dutch Golden Age, I will discuss the iconography of newspapers, written testimonies of reading in correspondence and private diaries, and ultimately newspapers as material objects to improve our understanding of reading habits in early modern Europe.

Looking at Reading

The history of printed newspapers in the Dutch Republic begins in 1618.Footnote11 Within a few years already, the city of Amsterdam would be regarded as the newspaper hub of early modern Europe. Its two corantos, issued by Jan van Hilten and Broer Jansz, were widely considered authoritative news media, and were read and copied throughout Europe.Footnote12 Both publishers produced a weekly paper every Saturday until the early 1650s with permission of the Amsterdam city council, a privilege which served to protect the publishers against other local competitors. Their layout was identical, and by all accounts very successful because it remained unchanged for almost a century: the corantos invariably opened with foreign bulletins, where the oldest news was listed first, and reports were preceded by dates and places of correspondence. This section was followed by information from the coranto’s own sources. On the whole, Van Hilten’s Courante uyt Italien & Duytschlandt (‘Coranto from Italy & Germany’) was considered the more reliable of the two. Van Hilten checked his sources whenever he could, and gave more space to exclusive stories, whereas Jansz, in his Tijdinghen uyt verscheyde quartieren (‘Tidings from Various Quarters’), assembled European news from a wider variety of places. Jansz was also more openly patriotic than his rival, which led to accusations that he reported only good news. But both papers enjoyed a healthy readership because, as one news addict put it, ‘one can always find something in one newspaper that is not available in the other’.Footnote13

The new medium flourished as a commercial product. Although handwritten newspapers remained in demand for a while, especially in higher circles, the printed coranto quickly established its preeminence as the leading genre in the market for news.Footnote14 Both Jansz and Van Hilten published French editions of their corantos for an international readership, and the latter also issued an English version. In the late 1630s and early 1640s, two more regular Amsterdam corantos saw the light, appearing on Tuesday and Wednesday respectively. In the mid-1640s, the number of competing titles increased to five.Footnote15 Corantos also appeared in other towns in the dense urban network of the United Provinces. In Delft a newspaper that derived its name from Van Hilten’s broadsheet can be traced back to 1623, and still existed under the same heading in the early 1640s. In the province of Gelderland the Arnhemsche Courante circulated in the 1620s and 1630s, and possibly longer. In the second half of the seventeenth century, The Hague, Leiden, Rotterdam, and Haarlem emerged as newspaper hubs that would occasionally rival Amsterdam for importance. By this time, most corantos appeared two or even three times weekly to provide a digest from the overload of foreign and domestic news. Some, like the Gazette d’Amsterdam or the Gazette de Leyde, appeared only in French. These newspapers in particular would be very successful across Europe in the eighteenth century.

Success, then as now, was measured by sales figures. Quantitative evidence is few and far between, but the print runs of seventeenth-century corantos must have been considerably lower than the 6000 copies that were printed on average of each of the four large newspapers in eighteenth-century Holland.Footnote16 From the scattered evidence, however, it appears that in the 1630s already Amsterdam coranteers had a broad circulation. Dozens of copies were sold to booksellers in other towns and provinces, sometimes in exchange for advertising space.Footnote17 Several seventeenth-century corantos had standing orders from government institutions—they were certainly read and discussed (and taken very seriously) by the authorities.Footnote18 Some of the copies, in addition, went to what we might term ‘professional’ newspaper readers: Foreign diplomats and news agents purchased corantos and sent them to their patrons abroad, like the Amsterdam engraver Michel le Blon who supplied the Swedish chancellor Axel Oxenstierna with a set of copies every week. Tsar Michael I of Russia had them translated and read out to him to stay informed.Footnote19 And some people collected newspapers to create an historical record. As a true news collector, the historian and diplomat Lieuwe van Aitzema had a standing order for two different newspapers with his local bookseller in The Hague.Footnote20 For his annual supply, Van Aitzema paid the sum of six guilders, which—if we disregard any rebates he may have negotiated—amounts to just over one stuiver per issue. This exceptionally low price is key to understanding the appeal of the printed newspaper in seventeenth-century Holland. One stuiver was a reasonable price even for the lower middle classes, who in the Holland towns might earn around 15–20 stuivers daily.Footnote21 When taking into account the high literacy rates in the Low Countries—around 60% for men and 40% for womenFootnote22—and the estimate that a single copy might have been read by as many as 10 different readers,Footnote23 this brings us back to Van Ostade and his visual glimpses of everyday life. Despite the scholarly attention for professional news mongers, the majority of printed newspapers was sold to readers belonging to the middle classes.

The iconography of newspapers in the Dutch Golden Age gives some clues as to the broad appeal of the coranto in seventeenth-century Holland. In 1673, Adriaen van Ostade created a breathtaking watercolor drawing entitled ‘News Reading at the Weavers’ Cottage’ (), which—like ‘The Newspaper Reader’ discussed before—depicts reading the coranto as a social event. Once again, the scene is a modest one, with one man holding the broadsheet to the light to read the bulletins and a second man and a woman actively listening to the latest news. In Haarlem, Van Ostade’s hometown, the weaving industry had suffered in the third quarter of the seventeenth century, and the weavers who had not relocated to Brabant had seen their revenues drop dramatically. Yet even in hard times, a newspaper, cheap as it was, could provide a moment of relief on a day of hard work. Taken together, the two Van Ostade designs of the 1670s reveal a typical way of depicting (and thinking about) newspapers in the United Provinces. Corantos, the images pertain, were read for a brief moment of leisure by urban dwellers of the middle classes who did not follow the news professionally. Since the broadsheets were cheap, and a single copy could be enjoyed by several people, reading newspapers could be considered a democratization of public affairs.

FIGURE 2 Adriaen van Ostade, Reading the News at the Weavers' Cottage (c. 1673). Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Art historians have long debated the realism of Dutch genre painting,Footnote24 but it is significant that in entirely different subgenres of the same period, other painters confirm the corantos’ broad popular appeal. In a painting of a surgeon’s shop by the Amsterdam artist Egbert van Heemskerck, it is hard to distinguish the man reading the coranto who is sitting in the background, waiting for his turn for bloodletting (). But a slip of paper on the back of the painting, in contemporary handwriting, reveals not only that the man is reading a ‘courant’, but also his identity, ‘the infamous Jan Knol’.Footnote25 Knol had a bad reputation in Amsterdam because he was a member of the Socinian movement, a radical anti-Trinitarian group that paved the way for the ideas of Spinoza and was fiercely combatted by hardliners in the Reformed Church. He had even done time in the urban prison. By the end of the 1660s, however, he was free to read a newspaper in a semi-public location. So through newspapers, foreign and domestic news was available to ordinary weavers and artisans as well as to dissidents. Scholars have pointed out that the history of newspaper reading has too often contented itself with implied or assumed readers,Footnote26 and these images too are not evidence of the actual reading of newspapers. But it is safe to assume that they could only have worked for contemporary viewers, as well as in the art market, if there was some element of truth in the broad appeal of printed newspapers. This is essentially corroborated by the regular inclusion of printed newspapers in the late seventeenth-century trompe l’oeil letter racks alongside other everyday matter such as feathered quills, pen knives, combs, handwritten letters, pamphlets, and sticks of sealing wax ().Footnote27

Writing on Reading

Textual evidence, moreover, supports and complements these glimpses of reading in visual culture. The two private diaries of the schoolmaster David Beck for the years 1624 (written in The Hague) and 1627–1628 (in Arnhem) could be regarded as the written equivalents of Van Ostade’s images. They are unique documents that capture the everyday life of the middle classes. As Jeroen Blaak has demonstrated in great detail, Beck was a keen reader.Footnote28 While residing in The Hague he went to Jan van Hilten’s bookshop every time he paid a visit to Amsterdam, but he also received corantos at home through friends or through the efficient postal network. The Amsterdam newspapers were generally on sale in other Holland towns within a day of their appearance.Footnote29 One summer evening, Beck discussed news from ‘the West Indian trade’ he had read over the course of the day with his mother-in-law, his wife’s uncle, and his illiterate niece.Footnote30 Bulletins in printed newspapers hence even trickled down to those for whom reading them was not an option. After having moved to Arnhem, the pattern was no different. Beck remained interested in political news, and read the local coranto whenever he could, often at a friend’s house or at home, like in May 1628 when he read a (premature) report about the relief of La Rochelle.Footnote31 In Arnhem, Beck frequented the bookshop of Johannes Janssonius, who published the local coranto. The bookshop was another place to read the coranto, and an excellent venue to discuss the latest news with other customers.Footnote32

However egalitarian these examples may seem to modern eyes, the ubiquity of political news was precisely what antagonized some contemporaries against the new genre of printed newspapers. Since early modern journalists—focused on commercial gain—lacked the social authority of private correspondents, and personal trust for those in higher circles was the cornerstone of credibility, newspapers were habitually accused of printing hearsay and lies. The wide availability of corantos, and the fact that the poor and ill-reputed had access to the exact same information as the more privileged classes initially undermined the newspapers’ integrity. One anonymous pamphleteer in the Southern Netherlands ridiculed Protestants north of the border for their addiction to news. In a fictional dialogue from 1635, a Remonstrant, a Counter-Remonstrant, and a Mennonite in Holland were united only in their desire to be informed about the latest rumors: ‘We must read the new Tidings, or we shall not have any patience’, they agreed, before quarreling vehemently over the implications of the printed bulletins.Footnote33 That newspapers facilitated disagreement on public affairs was another reason for caution.

Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft must have been among the newspapers’ fiercest critics. Hooft was the leading playwright of the early Dutch Golden Age, and a descendant of one of the most respected Amsterdam regent families. During the summer he resided in Muiden Castle, 10 miles east of the city, where he depended for political information on the weekly newspapers his cousin forwarded to him. Hooft read multiple newspapers, compared bulletins in Dutch and foreign media, and occasionally mentioned that the papers had occupied him until late at night.Footnote34 If bad weather conditions delayed their arrival, Hooft sent a messenger to Amsterdam to satisfy his curiosity.Footnote35 But at the same time, Hooft was suspicious of the standard of journalism. Many of his letters begin with a diatribe against the printed press. ‘I return to you the newspapers, which I am afraid have become so used to lying that they report less than the truth’, he wrote when the Amsterdam corantos quoted a much lower revenue for the annual Spanish treasure fleet than Hooft had anticipated.Footnote36 Copy from the unpredictable Thirty Years’ War he distrusted almost by default, and specific criticism often served as a stepping stone for a more general dismissal of the genre: ‘Rumours from Magdeburg speak in two tongues. So it goes with the newspapers, who lose some of their feathers and add false ones instead’, or: ‘the newspapers report good news from Germany, but so flimsily that for confirmation I choose to await the arrival of a cripple messenger’.Footnote37 The people Hooft corresponded with tended to agree with him. Caspar Barlaeus, founding professor of Amsterdam’s Athenaeum Illustre, once wrote that ‘these and other things I have understood from the weekly chronicles, who print tenacious inventions alongside truthful reports’.Footnote38

Arguably the most astute follower of Dutch politics, the lawyer Hugo Grotius, was a contemporary of Hooft and Barlaeus. He had been exiled for his unorthodox religious views, and had good reason to be skeptical about the endless discussions in Dutch political circles. He corresponded about news mainly with his brother-in-law Nicolaes van Reigersberch, a judge at the High Council in The Hague who was often better informed than the leading Amsterdam journalists. Grotius mainly relied on him in the 1630s, when for personal reasons he was hoping for another Truce with Spain which might enable him to return to the Dutch Republic.Footnote39 These secret negotiations rarely made it into the newspapers, demonstrating also the limitations of publicly available information. But for other developments, mostly but not exclusively from abroad, newspapers for Grotius were a valuable source of information. In January 1642 news arrived of the Dutch capture of the Portuguese slave station in Angola—a crucial victory because it gave the West India Company a de facto monopoly over the Atlantic slave trade. The news, arriving in Amsterdam via Brazil, had long been anticipated. Van Reigersberch, as always, immediately wrote to Grotius in Paris, but this time he sent printed evidence as well: ‘The certain tidings we have received here from Africa you will see for yourself in the printed coranto I attach to this letter’, a reference to Van Hilten’s Courante which had appeared in Amsterdam two days before.Footnote40 Van Reigersberch presented the weekly newspaper as the ultimate confirmation of specific geopolitical developments, news that both he and Grotius had been waiting for ever since information of the intended campaign had first reached them a few months before.

Amidst all the sneers, then, it is important to emphasize that even highly critical people continued to read newspapers. When we consider the consumption of ‘new media’ like the coranto in early modern Europe, and think of our own strategies today of managing the flow of news, it is perhaps useful to disentangle the different opinions of different generations. Hooft, Barlaeus, and Grotius, all born in the 1580s, were already middle-aged when printed newspapers began to appear, and may have been more reluctant to embrace the new genre than younger readers for whom the corantos were a fact of everyday life. In the later seventeenth century, as newspapers grew in numbers and frequency, paintings of members of the regent class also began to depict the reading of newspapers. In the 1690s, we encounter a portrait of a magistrate, a certain Herman de Neydt, holding a copy of the Amsterdamsche Courant in his hand. The increased acceptance of reading newspapers in the upper echelons is (again) corroborated by scant written evidence, such as the diary of the aristocratic Pieter Teding van Berkhout.Footnote41 Foreigners commented on the impact of newspapers in the Dutch Republic with a mixture of disbelief and loathing. ‘Everyone reads them here’, the French ambassador Jean Antoine de Mesmes, Count d’Avaux, remarked in the 1680s.Footnote42 Diplomats occasionally protested to the States-General when newspapers published information they considered inappropriate, fueling the regents’ apprehension.Footnote43 At the end of the seventeenth century, the authorities slowly managed to reduce the number of newspaper titles to one in every town—facilitating a more effective policy of censorship. This perhaps explains why by 1700 it became acceptable for members of the higher classes to be portrayed while holding a newspaper. The frustration of some of the more traditional forces in society remained. Jacobus Hondius, an orthodox Reformed minister from Hoorn, lamented in a catalogue of sins committed by ordinary churchgoers that

Church members read the Corantos two or three times (or listen to them being read), but do not read or listen to the Word of God one single time. Such people, then, spend much more time with the newspaper than with the Bible, which is not the way of the righteous.Footnote44

Managing the News: Reading Habits

What remains is the question of how readers in the Dutch Golden Age managed the flow of news. Blaak has already pointed to the different kinds of reading in the seventeenth century, and the difficulty to establish a pattern in reading modes.Footnote45 The problem with reading newspapers, too, is that every incidental piece of evidence throws up a number of new complications. The schoolmaster David Beck, for example, wrote in his 1624 diary that with two friends he walked ‘straight to the Voorhout, in and out of the plantation, resting there on a bench beneath the cool and pleasant foliage of the green trees for a long while, until I had read the printed Courant in its entirety’.Footnote46 The latter part of Beck’s remark in particular is problematic. Apparently Beck considered the fact that he had read all of that week’s bulletins noteworthy, and the reference to the unusual tranquility implies that the schoolmaster did not always read the entire newspaper, perhaps for lack of time.Footnote47 Will Slauter has recently argued for the importance of the paragraph as the most natural unit of early modern news, and if again we briefly reflect on how we read newspapers today, then we should consider that despite the relatively small amount of text in the weekly newspapers of the Dutch Golden Age, many people must have read only certain sections.Footnote48 Which sections they preferred must have depended on their personal interest. Some readers may have been interested mainly, or exclusively, in news from Italy, Germany, or England. It is also conceivable that the horizontal line the Amsterdam coranteers printed to separate foreign and domestic news served as a textual anchor, pointing readers towards the section that for many may have been the most relevant.Footnote49

Another reading habit that is implied in the diaries of David Beck (but equally difficult to grasp) is the irregular consumption of news. The appearance of extraordinary issues whenever there was breaking news suggests that journalists knew they would sell more copies than during the regular news cycle. Only when there was important news did Beck comment on it in his private papers. There is no indication, however, that Beck read the weeklies every week, and this must have been the case for many non-professional readers. Since most printed newspapers of the seventeenth century have only survived haphazardly, modern scholars often find that based on two or three copies that may be have been published several weeks apart, it is difficult to properly understand the full background to an early modern storyline. Yet this was almost certainly different for urban residents like David Beck. The media landscape in the Dutch Republic was sufficiently well developed for him to rely on what he heard from others in the weeks or months in between to understand what the newspapers reported, even if he read only the occasional coranto. But just what determined when he read a coranto, and why then, remains unclear for now.

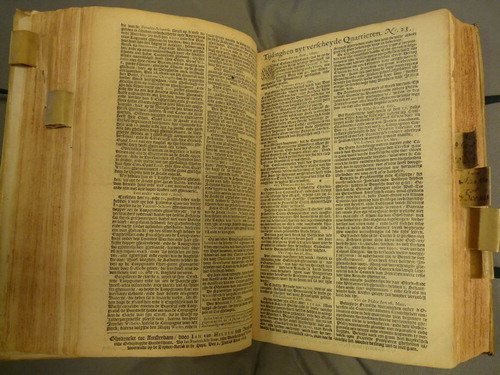

Yet another aspect of interest is the persistent attraction of news, until long after the political momentum had receded. Here the newspaper as a physical object can provide useful evidence. The National Library of the Netherlands in The Hague holds a hefty volume which contains over 500 printed newspapers, consecutive issues for the period between April 1626 and October 1635. Only in the years 1631 and 1632 does the collection show accidental gaps, but in total there are just four issues missing ().Footnote50 The volume was constructed by a contemporary reader, who not only read the newspaper every week, but also retained them, perhaps as a reference work. For that reason, presumably, he had them bound in the seventeenth century. The identity of the reader is unknown, but since the collection stops rather abruptly, it is possible that the newspapers were collected by someone who died in late October or early November 1635, but that, at this point, is purely speculative. Another possibility is that the volume was created by a professional reader, a clerk for example trusted with the task to safeguard the collective memory of an institutional body like the States of Holland or the States-General.Footnote51 What is certain is that the volume changed hands on 22 October 1698—according to handwritten notes on the inside of the cover—and was ultimately sold to the National Library in 1810.Footnote52

There are no contemporary letters, diaries, or visual images reflecting on the habit of collecting newspapers in the Dutch Golden Age. Hooft, for instance, after having read them, always returned the corantos to his supplier in Amsterdam. Advertisements in eighteenth-century periodicals, however, offer evidence that the owner of the volume now in the National Library was not the only reader who stored seventeenth-century newspapers for use at a later date. In November 1740, one bookseller announced an auction in his shop in The Hague ‘which includes an extraordinary and considerable collection of Holland newspapers from the year 1635 until today, complete from 1679 to the last day of June 1740, consisting of 28 Volumes bound in Parisian bindings and in good condition’.Footnote53 Also in the mid-eighteenth century, according to Hannie van Goinga, a paper merchant in Amsterdam requested

anyone who has old corantos, whether they are printed in Amsterdam, The Hague, Leiden, Haarlem, or elsewhere, from the years between 1680 and 1750 or from later or singular years, to let him know, because he will buy them for a good price.Footnote54

Finally, there is another reading habit that can be traced in the early seventeenth-century collection in the National Library in The Hague. A comparison between the two early Amsterdam newspaper titles it contains shows that the two journalists may well have targeted different audiences. Different readers, however, presumably looked for different things in a newspaper. What is clear from the corantos the anonymous reader assembled is that he preferred Jan van Hilten’s Courante over Broer Jansz’ Tijdinghen. This brings us to the intriguing matter of loyalty to a particular newspaper title—very common today, but never previously the subject of study in early modern times. The volume in The Hague begins in the spring of 1626 with 16 consecutive issues of the Tijdinghen, but then switches to Van Hilten’s Courante for the second half of the year. It includes four or five extraordinary issues Van Hilten printed when he wanted to be the first to bring news of certain events, and perhaps this was one of the selling points that made the reader switch to Van Hilten after initially reading Jansz. The next year, 1627, all 52 issues came from Van Hilten’s workshop. In 1628, it was again mainly Van Hilten, apart from two issues (on 5 February and 6 May) of Jansz’ Tijdinghen. One plausible interpretation would be that Van Hilten’s newspaper may have sold out, and that this reader, of whom we do not know how far away he lived from the Amsterdam printing houses, was obliged to buy a copy of Jansz’ paper instead to complete his collection. By now, however, his volume displayed a strong preference for Van Hilten’s Courante.

But then, in 1629, something fascinating happens. From January to mid-May, our reader buys Van Hilten’s paper as usual, but then he switches, by all accounts deliberately, to Jansz’ Tijdinghen. The first issue of Jansz’ coranto, from 26 May 1629, contains news that has come almost exclusively from ‘s-Hertogenbosch (Bois-Le-Duc) where the troops of stadholder Frederik Hendrik had just started their long-awaited siege of the city after a succession of victories over Spanish troops in Gelderland and in Wesel. Broer Jansz, in his imprint, fashioned himself as a ‘former Coranteer in the army of the Prince’, probably a reference to the previous stadholder Maurits, but a claim of authority that may not have been lost on newspaper readers in the early seventeenth-century United Provinces. Indeed, by the time the siege of Den Bosch reached its climax in the summer, Jansz’ bulletins are more extensive than those of Van Hilten. We can witness that our reader continues to read Jansz’ Tijdinghen throughout the summer and the fall, until 10 November, when the siege of Den Bosch had been completed successfully, and the main media event of the year was gradually being pushed to the background by the more regular news flow. The last six newspapers of the year 1629 in this collection are once again issues of Van Hilten’s Courante. It appears that the nature and the origins of the news determined which newspaper people preferred, especially people like our reader who must have had a good understanding of the different styles of reporting and—we might infer—the media landscape of the Dutch Republic in general.

For the next five years, our reader remains loyal to Jan van Hilten. These are the years when news from the Atlantic world featured very prominently in the Amsterdam newspapers, and as I have demonstrated elsewhere, Van Hilten’s bulletins on events in Brazil and the Caribbean were much more reliable than those of Jansz.Footnote56 However, almost as if to confirm the deliberate nature of the choice he made in 1629, six years later, in 1635, the reader again changes to Jansz. From 1 September, for a period of 10 weeks, he buys not only the Tijdinghen, but also continues to buy copies of Van Hilten’s newspaper (for 8 out of the 10 weeks concerned). This time, the reader’s decision to turn to Broer Jansz is again based on breaking domestic news, in this case the unexpected fall of the strategic fortress at Schenkenschans—in the Duchy of Cleves just across the Dutch border. Very soon after the Dutch had surrendered the stronghold, in the final days of July, the campaign to recapture it commenced, and, again, it is at this very moment that our reader turns to Jansz for news from the stadholder’s quarters. For 10 consecutive weeks, he must have been meticulously comparing the domestic news bulletins in Van Hilten and Jansz’ newspapers. How he assessed these complementary reports—and whether or not this would have changed his preference again—remains unclear because he stopped collecting newspapers, in this volume at least, 10 weeks after Frederik Hendrik’s siege of Schenkenschans had started, a siege that would be successful only in April of the following year.

Once again there are more questions than answers. Were readers from the (lower) middle classes also aware of the different tone of reporting in different newspaper titles? Was the difference in reporting styles significant enough for professional readers to read multiple newspapers at the same time? Did members from different political factions—or different social groups—identify with different newspapers? One thing the close reading of this particular volume implies is that while scholars generally presume that newspapers copied each other, or slavishly followed the commandments of the government they served, readers in the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic benefited from an open media landscape in which they could choose to read different media, depending on personal preference or on the nature of news and the style of reporting. Even in two newspapers that at first glance were so similar as Jan van Hilten’s Courante and Broer Jansz’ Tijdinghen, the bulletins on key domestic developments varied enough for readers to switch from one newspaper to the other for the duration of—for example—the ongoing siege of a strategic town. Finally, as an aside, the volume in the National Library serves as a warning in an age of digitization: Despite the many new possibilities that newspaper databases offer to scholars, some or our most pressing questions cannot be answered by consulting these sources online.

Conclusion

Based on a combination of visual and textual evidence from the Dutch Golden Age, it transpires that newspapers were consumed by a cross-section of society—urban and rural, rich and poor. For many, reading newspapers was a social event. Single issues were shared by multiple readers, and read together at home, at work, or in public places like bookshops. The implications of the events newspapers reported on were discussed with others who had not read them or could not read at all, increasing the scope of the genre even beyond the literate middle classes. That newspapers democratized political affairs and facilitated dissent explains why the elite, deprived of its monopoly on information, received the ‘new media’ with scepsis, although they did read them. As the authorities curtailed the freedom of the press, the reputation of newspapers gradually improved.

Studying individual testimonies of readership allows us to go beyond the usual group of implied or assumed readers. Personal accounts—in the shape of diaries, letters, or carefully crafted collections that have survived until today—reveal a variety of reading habits to manage the perceived unreliability of newspapers and, as the seventeenth century progressed, the overload of foreign and domestic bulletins. However, many questions still remain to be answered. Some readers may have been interested only in certain sections of the broadsheets, because it is unlikely that everyone had the time to read everything. Did those with an interest in news read a coranto every week, and if not, why not? What exactly made readers decide to purchase (or borrow) a copy? If given a choice, what made readers decide which newspaper to read? And why did some readers collect their newspapers and hold on to them for many decades? More research is required to answer these questions, but any future scholar of newspaper reading must take into account the wide variety of primary sources available. Especially when combined, they can offer us a better understanding of a routine that continues to play a part in everyday life even today.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCiD

Michiel van Groesen http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6421-6033

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michiel van Groesen

Michiel van Groesen, Institute for History, Leiden University, Leiden, The Netherlands.

Notes

1. For a good recent overview of the field of early modern news, see Pettegree, Invention of News.

2. Dooley, “News and Doubt.”

3. Jardine and Grafton, “Studied for Action” is the most famous, but by no means the only example. See also Arnoud Visser’s Utrecht University website Annotated Books Online: http://www.annotatedbooksonline.com/ (Accessed May 10, 2016).

4. Sharpe, Reading Revolutions; Loveman, Samuel Pepys, esp. 80–107.

5. Raymond, Invention of the Newspaper, 232–68.

6. Wittmann, “Was There a Reading Revolution,” 284–5.

7. Goinga, Alom te bekomen.

8. Blaak, Literacy.

9. In addition to Raymond, see also Frearson, “Distribution and Readership,” 1–25; Welke, “Gemeinsame Lektüre,” 29–53.

10. The notion of a Dutch ‘discussion culture’ was introduced by Frijhoff and Spies, 1650: Hard-Won Unity, 220–5.

11. The bibliographical benchmark was set by Folke Dahl in Dutch Corantos, with excellent introductions and 334 facsimiles from Swedish collections. For the period before the printed newspaper, see Stolp, Eerste couranten.

12. Pettegree, Invention of News, 188–90; Couvée, “First Coranteers,” 22–36; and Lankhorst, “Newspapers,” 151–9.

13. This remark, often quoted, is from a letter Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft wrote to his cousin Joost Baek, see Tricht, Briefwisseling, no. 474 (August 25, 1631). For scathing remarks about Jansz’ reliability, see Borst, “Broer Jansz,” 86. For a comparison between Van Hilten and Jansz, see Groesen, “(No) News,” 739–60.

14. Stolp, Eerste couranten, 83–4.

15. Dahl, Dutch Corantos, 70–82.

16. Goinga, Alom te bekomen, 36.

17. Lankhorst, “Newspapers,” 152.

18. Gelder, Getemperde vrijheid, 186–7; Stolp, Eerste couranten, 9, 83–4.

19. Keblusek, “Business of News,” 205–13; Maier, “Zeventiende-eeuwse Nederlandse couranten,” 27.

20. Keblusek, Boeken, 329–35. When Van Aitzema began to purchase three copies weekly of the Opregte Haerlemsche Courant in 1658, the price rose to just under one stuiver per issue.

21. Vries and Van der Woude, First Modern Economy, 609–21, esp. Table 12.1, p. 610. As the distribution of newspapers professionalized and print runs increased, prices dropped to ½ stuiver for a copy of the Leydse Courant in the 1770s. See Goinga, Alom te bekomen, 36.

22. Frijhoff and Spies, 1650: Hard-Won Unity, 236–7.

23. Welke, “Gemeinsame Lektüre,” 30, 45; Harris, London Newspapers, 190.

24. For the extensive iconological debate that began in the 1980s and is to some extent still ongoing, see first and foremost Alpers, Art of Describing and Jongh, Zinne- en minnebeelden.

25. See the catalogue of the Amsterdam Museum’s collection: http://am.adlibhosting.com/ (last visited 10 May 2016).

26. Raymond, Invention of the Newspaper, xiii.

27. Wahrman, Mr. Collier; Illusions: Gijsbrechts.

28. Blaak, Literacy, 41–111, with references to newspapers on pages 92, 94, 100, 104, and 110.

29. Borst, “Van Hilten,” 131–8.

30. Beck, Spiegel, 159.

31. Beck, Mijn voornaamste daden, 173.

32. Ibid., 56.

33. Geusen-gheschreeuw, [A2r]:

Mennist: ‘Siet de lieden staen op hoopen / My dunckt sy nieuwe Tijdingh coopen; Arminiaen.: Iae Maet laet ons nu wel hoepen / Hoort de nieuwe Tijdigh roepen; Gom.: De nieuwe Tijdingh moet ick lesen / Oft ick can niet gherust ghewesen’.

34. Tricht, Briefwisseling, no. 378 (Hooft to Baek, 18 August 1630): ‘Zijn geselschap ende ’t lezen van zoo veele tijdingen hebben mij te diep inden avont gevoert, om dezen [brief] te verlengen’.

35. Ibid., no. 398 (Hooft to Baek, 29 September 1630): ‘De tijdingen van eergisteren maekten mij zoo toghtigh nae ’t vervolgh, dat ick, de veerschujt door onweder met mijne brieven terug gedreven zijnde, eenen bode met dezelve afvejrdighde, om aen naeder bescheidt te geraken’.

36. Ibid., no. 388 (Hooft to Baek, 10 September 1630): ‘Ziet UE hier weder toekomen de loopmaeren, die ick vreeze dat den mondt zoo zeer tot lieghen gewent hebben, datze in ’t begrooten vande Indische schatten, ons min als de waerh zeggen’. See in greater detail: Groesen, “(No) News,” 756–7.

37. Ibid., no. 458 (Hooft to Baek, 1 June 1631):

De geruchten van Maeghdenburgh, zijn voorwaer, om eenen, de hairen te berghe te doen staen. Maer zij spreken ujt geen' eenen mondt. Dat 's een kranke troost. Want de versche tijdingen hebben 't voor een' manier. Zij wassen onderweegh: laeten ‘er van haer’ veeren, en krijghen valsche, in de steê;

38. Ibid., no. 928 (Barlaeus to Hooft, 23 August 1638): ‘Sed haec aliaque ex fastis hebdomadalibus intellexisti, chartulis tam ficti pravique tenacibus, quam veri nunciis’. For a similar analysis for early modern Italy, see Dooley, “News and Doubt,” 275–90.

39. Nellen, Lifelong Struggle, 402–3.

40. Molhuysen, Briefwisseling, no. 5555 (Van Reigersberch to Grotius, 13 January 1642): ‘De seeckere tijdynge die wij hier uyt Africa hebben, sal uEd. sien uyt de bijgaende gedruckte courante’. The reference is to the Courante uyt Italien en Duytschlandt of 11 January, with coverage of Cornelis Jol’s raid on São Paulo de Luanda in August 1641.

41. https://rkd.nl/nl/explore/images/131340 (last visited 10 May 2016). See Blaak, Literacy, 113–87.

42. Sas, “The Netherlands,” 50.

43. Weekhout, Boekencensuur, 55–6.

44. Hondius, Swart register, 71–2:

Sondigen soodanige menschen, die Ledematen zijnde, nochtans de Couranten precijs tweemael of driemael ’s weecks lesen of hooren lesen, maer Gods Woordt in een geheele weeck wel niet eenmael lesen of hooren lesen: Soo dat sulcke menschen veel meer werck maecken van de Courant, als van de Bijbel.

45. Blaak, Literacy, 99–105.

46. Beck, Spiegel, 143.

47. Blair, Too Much to Know.

48. Slauter, “Paragraph,” 253–78.

49. Couvée, “First Coranteers,” 23–6.

50. The volume is catalogued as call number 341.A.1. The missing issues are from 14 June and 23 August 1631, and 24 January and 17 April 1632.

51. This was first suggested to me during the Amsterdam conference Managing the News in Early Modern Europe by Joop Koopmans, and later also by Paul Knevel, both of whom worked extensively with documents from these political bodies.

52. I checked public auctions in October 1698 for a volume of printed newspapers of the late 1620s and early 1630s in www.bibliopolis.nl (last visited 10 May 2016), but to no avail.

53. Leydse Courant, 16 November 1740:

Jacobus van den Kieboom, boekverkoper in ’s Hage in de Spuystraat, zal op Morgen, zynde Donderdag den 17 November, ten zynen Huyze verkoopen een fraaye Versameling van wel geconditioneerde Latynsche, Fransche en Nederduytsche BOEKEN, waar onder is een extra-ordinaire en considerabele Collectie van Hollandsche Couranten zedert het Jaar 1635 tot nu toe, zynde dezelve zedert 1679 tot den laatste Juny 1740 compleet, bestaande in 28 Deelen in Parysse Banden gebonden wel geconditioneerd.

54. Goinga, Alom te bekomen, 32, n. 9, where I also found the advertisement mentioned in the previous footnote. The full quote in Dutch is:

Adam Meyer, Papierverkoper t’Amst in de Barberstraat, verzoekt een ieder indien hy oude Couran[t]en het zy Amsterdamsche, ’s Gravenhaegse, Leydsche, Haerlemsche of andere mogt hebben van de jaeren 1680 tot 1750 incluis, of eenige volgende, of aparte jaeren, gelieven zulks op te geeven aen de bovengemelde die dezelve zal kopen en daer voor een goede prys betaelen.

55. Sautijn Kluit, “’s-Gravenhaagsche Courant,” 37.

56. Groesen, “(No) News,” 739–60.

Bibliography

- Alpers, Svetlana. The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983.

- Annotated Books Online. http://www.annotatedbooksonline.com/.

- Arblaster, Paul. From Ghent to Aix: How They Brought the News in the Habsburg Netherlands, 1550–1700. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

- Beck, David. Mijn voornaamste daden en ontmoetingen: Dagboek van David Beck, Arnhem 1627–1628, ed. Jeroen Blaak. Hilversum: Verloren, 2014.

- Beck, David. Spiegel van mijn leven: Haags dagboek 1624, ed. Sv. E. Veldhuijzen. Hilversum: Verloren, 1993.

- Blaak, Jeroen. Literacy in Everyday Life: Reading and Writing in Early Modern Dutch Diaries. Leiden: Brill, 2009.

- Blair, Ann. Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information Before the Modern Age. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Borst, Henk. “Broer Jansz in Antwerpse ogen: De Amsterdamse courantier na de slag bij Kallo in 1638 neergezet als propagandist.” De zeventiende eeuw 25, no. 1 (2009): 73–89.

- Borst, Henk. “Van Hilten, Broersz en Claessen: Handel in boeken en actueel drukwerk tussen Amsterdam en Leeuwarden in 1639.” De zeventiende eeuw 8, no. 1 (1992): 131–138.

- Cavallo, Guglielmo, and Roger Chartier, eds. A History of Reading in the West. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

- Couvée, Dirk H. “The First Coranteers—The Flow of the News in the 1620s.” Gazette: International Journal for Mass Communication Studies 8 (1962): 22–36. doi: 10.1177/001654926200800102

- Dahl, Folke, ed. Dutch Corantos, 1618–1650: A Bibliography. Göteborg: Stadbibliothek, 1946.

- Dooley, Brendan. “News and Doubt in Early Modern Culture. Or, Are We Having a Public Sphere Yet?” In The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe, edited by Brendan Dooley and Sabrina Baron, 275–290. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Enno van Gelder, H. A. Getemperde vrijheid: Een verhandeling over de verhouding van kerk en staat in de Republiek der Verenigde Nederlanden en de vrijheid van meningsuiting in zake godsdienst, drukpers en onderwijs, gedurende de 17e eeuw. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff, 1972.

- Frearson, Michael. “The Distribution and Readership of London Corantos in the 1620s.” In Serials and Their Readers, 1620–1914, edited by Robin Myers and Michael Harris, 1–25. Winchester: St. Paul Bibliographies, 1993.

- Frijhoff, Willem, and Marijke Spies. 1650: Hard-Won Unity. Assen: Van Gorcum, 2004.

- van Goinga, Hannie. ‘Alom te bekomen’: Veranderingen in de boekdistributie in de Republiek, 1720–1800. Amsterdam: De Buitenkant, 1999.

- van Groesen, Michiel. “(No) News from the Western Front: The Weekly Press of the Low Countries and the Making of Atlantic News.” Sixteenth Century Journal 44, no. 3 (2013): 739–760.

- Harris, Michael. London Newspapers in the Age of Walpole: A Study in the Origins of the Modern English Press. London: Associated University Presses, 1987.

- Het Geusen-gheschreeuw: Behelsende hoe de Gommaristen, Mennisten ende Arminianen hebben gheroepen over die groote Victorie. s.l., s.a. [1635].

- Hondius, Jacobus. Swart register van duysent sonden. Amsterdam: Borstius, 1679.

- Illusions: Gijsbrechts, Royal Master of Deception. Copenhagen: Statens Museum fur Kunst, 1999.

- Jardine, Lisa, and Anthony Grafton, “‘Studied for Action’: How Gabriel Harvey Read His Livy.” Past and Present 129 (1990): 30–78. doi: 10.1093/past/129.1.30

- de Jongh, Eddy. Zinne- en minnebeelden in de schilderkunst van de zeventiende eeuw. Amsterdam: Nederlandse Stichting Openbaar Kunstbezit, 1967.

- Keblusek, Marika. Boeken in de Hofstad: Haagse boekcultuur in de Gouden Eeuw. Hilversum: Verloren, 1997.

- Keblusek, Marika. “The Business of News: Michel le Blon and the Transmission of Political Information to Sweden in the 1630s.” Scandinavian Journal of History 28, no. 3/4 (2003): 205–213. doi: 10.1080/03468750310003640

- Lankhorst, Otto. “Newspapers in the Netherlands in the Seventeenth Century.” In The Politics of Information in Early Modern Europe, edited by Brendan Dooley and Sabrina Baron, 151–159. London: Routledge, 2001.

- Loveman, Kate. Samuel Pepys and His Books: Reading, Newsgathering, and Sociability, 1660–1703. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Maier, Ingrid. “Zeventiende-eeuwse Nederlandse couranten vertaald voor de tsaar.” Tijdschrift voor Mediastudies 12 (2009): 27–49.

- Molhuysen, P. C., B. L. Meulenbroek, Paula P. Witkam, Henk J. M. Nellen, and Cornelia M. Ridderikhoff eds. Briefwisseling van Hugo Grotius, 1597–1645. 17 vols. The Hague: Nijhoff, 1928–2001.

- Nellen, Henk. A Lifelong Struggle for Peace in Church and State, 1583–1645. Leiden: Brill, 2015.

- Pettegree, Andrew. The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know about Itself. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Raymond, Joad. The Invention of the Newspaper: English Newsbooks, 1641–1649. 2nd rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, [1996] 2005.

- van Sas, Niek. “The Netherlands, 1750–1813.” In Press, Politics and the Public Sphere in Europe and North America, 1760–1820, edited by Hannah Barker and Simon Burrows, 48–68. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Sautijn Kluit, W. P. “De ‘s Gravenhaagsche Courant.” Handelingen en mededeelingen van de Maatschappij der Nederlandsche letterkunde over het jaar 1874-1875 (1875): 3–178.

- Sharpe, Kevin. Reading Revolutions: The Politics of Reading in Early Modern England. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Slauter, Will. “The Paragraph as Information Technology: How News Traveled in the Eighteenth-Century Atlantic World.” Annales H.S.S. II (2012): 253–278.

- Stolp, Annie. De eerste couranten in Holland: Bijdrage tot de geschiedenis der geschreven nieuwstijdingen. Haarlem: Enschedé, 1938.

- Tricht, H. W. van, ed. De briefwisseling van Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft. 3 vols. Culemborg: Tjeenk Willink, 1976–1979.

- de Vries, Jan, and Ad van der Woude. The First Modern Economy: Success, Failure, and Perseverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500–1815. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Weekhout, Ingrid. Boekencensuur in de Noordelijke Nederlanden. De vrijheid van drukpers in de zeventiende eeuw. The Hague: SDU, 1998.

- Welke, Martin. “Gemeinsame Lektüre und frühe Formen von Gruppenbildungen im 17. und 18. Jahrhundert: Zeitungslesen in Deutschland.” In Lesegesellschaften und bürgerliche Emanzipation: Ein europäischer Vergleich, edited by Otto Dahn, 29–53. Munich: Beck, 1981.

- Wharman, Dhor. Mr. Collier’s Letter Racks: A Tale of Art & Illusion at the Threshold of the Modern Information Age. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Wittmann, Reinhard. “Was There a Reading Revolution at the End of the Eighteenth Century?” In A History of Reading in the West, edited by Guglielmo Cavallo and Roger Chartier, 284–312. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.