Abstract

This article compares the content and quality of mid-eighteenth-century news accounts about the 1748 conclusion of peace in Aix-la-Chapelle that were published in Dutch newspapers and news digests. It also assesses the position of news digests between newspapers that included topical information and historiography. This case demonstrates that while newspapers can be considered as a first step in the writing of history, news digests offered a further step. Newspapers provided factual information ordered according to chronological principles, yet due to incorrect sources and uncertainties also included mistakes and rumors. By making better news summaries and providing commentary, news digest editors could avoid such failures and had more time and opportunity to put facts into perspective. They could also reflect on the news via artistic interpretations, such as allegorical engravings. The case shows the different ways news was managed in the Dutch Republic’s mid-eighteenth-century news media.

In August 1744, Dutch newspapers advertised a new half-year volume of the news digest Nederlandsch gedenkboek of Europische MercuriusFootnote1 (Dutch Chronicle or European Mercury), covering the period January–June 1744. Its Amsterdam publishers, Bernardus van Gerrevink and the Ratelband Heirs, recommended the edition as a work of great value because of ‘the circumstances of the time’. Their announcement also promoted the sale of previous volumes covering the period 1740–1743, by stating that those issues would provide ‘a complete history’ of the years since Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI had passed away.Footnote2 In February 1745, similar advertisements were placed in Dutch newspapers for the next half-year volume of the Europische Mercurius, concerning the period July–December 1744. In this case, the advertisement text continued with the phrase that previous volumes, dealing with the years from 1740, would give an account of all acts of war and state between the death of Emperor Charles VI and the moment his successor Charles VII had passed away.Footnote3 The last phrase should not be taken too literally since the emperor’s death, on January 20, 1745, would be reported in the succeeding volume that was still in the editor’s hands.Footnote4 However, when these advertisements were published in February 1745, potential buyers of the Europische Mercurius were already familiar with Charles VII’s death as this occurrence had been reported in Dutch newspapers at the end of January. They undoubtedly grasped the intent of the publisher’s marketing text.Footnote5

Advertisements of this kind suggest that the Europische Mercurius publishing company considered its news periodical series as a kind of reference tool presenting historical surveys about all kinds of topics, particularly if readers consulted several successive volumes dealing with those affairs. The difference between the content of news digests on the one hand and newspapers on the other was, of course, largely a consequence of their distinctive production processes. News digests differed from newspapers because the digests’ editors had far more time to prepare and compose their issues than newspapermen, who had to edit the latest news reports into short messages within a few hours or days. News digest editors, on the other hand, could collect, select and transform chains of news reports about related topics into new, coherent accounts over a period of weeks or months, depending upon the frequency of their periodicals and the publication policies of their publishers. These editors often provided their narratives with contextual information and editorial remarks, a process which was time-consuming and therefore less feasible for newspapermen. Besides, commentary was rather unusual in early modern Dutch newspapers, which were not yet regarded as media for critical observations.Footnote6

Early modern news editors—of both newspapers and news digests—did not cite their sources on a regular basis. This impedes the exploration of contemporary news networks in which various types of news suppliers and correspondents functioned. Nevertheless, research on early modern news-gathering has demonstrated that copy-and-paste practices were very common. Many newspapers included reports with almost or even exactly the same content as had been published in other newspapers, aside from small differences in spelling and printer’s errors. Translations of the same sources by different editors typically led to different versions, but even then the basic information generally remained the same.Footnote7

So far, research about the transformation of early modern newspaper items and other news sources into news digest accounts and also contemporary historiography is scarce.Footnote8 However, scholars of media history have assumed that news digest editors summarized newspaper reports into their own accounts.Footnote9 During the sixteenth century, news reports were already also being used as sources for history books, as Silvia Serena Tschopp, for example, demonstrated in her study about Georg Kölderer’s Augsburg chronicle, and Joad Raymond in his research about the relation between early English newsbooks and historiography concerning the English Civil War.Footnote10

The rarely demonstrated assumption about the subsequent lives of newspaper reports in news digests will be tested in this article by exploring the following questions: to what extent do early modern newspaper reports resemble the accounts in news digests? Furthermore, how were the digests’ accounts integrated with other news sources, such as letters, pamphlets and official documents? In other words, this article will scrutinize similarities and differences in content and quality between newspapers and news digests. Moreover, it will assess the position of those digests between news media, which included chiefly topical information, and contemporary historiography.

Employing news about the 1748 conclusion of peace in Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen) as an example, the subsequent reflections on these themes will focus on Dutch news media of the late 1740s. It can be argued that the signing of this treaty is a particularly suitable topic for this research. It took place in a period during which not only a substantial number of newspapers was published across the Dutch Republic, but also in an era in which several news periodicals appeared. Consequently, a solid comparative analysis can be made. Furthermore, since Aix-la-Chapelle was situated very close to the Dutch Republic, it can be assumed that Dutch newspapers would have used their own methods of news-gathering for the fast coverage of the peace conclusion instead of copying the news about this occurrence from foreign newspapers or other Dutch newspapers. A close comparative examination of these newspapers will lead to a better insight into their functioning.

The article will first analyze reports of the Peace in newspapers and then compare their reports with those in news periodicals. Subsequently, these news digests—and in particular the Europische Mercurius as the most established news digest of the time—will be situated between the newspapers and contemporary historiography.

The 1748 Peace in Dutch Newspapers

On October 18, 1748, in the German city of Aix-la-Chapelle, representatives of Great Britain, France and the Dutch Republic signed a treaty that marked the end of the War of the Austrian Succession. It was a joyful event for the Dutch Republic, ending an anxious period for the country after its invasion by France. The conflict had begun in 1740 when Prussia’s King Frederick II had disregarded the so-called Pragmatic Sanction by conquering the Habsburg territory of Silesia. Emperor Charles VI had issued this edict in 1713 to ensure that his daughter Maria Theresa would govern all the Austrian Habsburg hereditary lands after his death. As usual in European international politics of the time, other countries had become involved in the conflict as a result of alliances and obligations. The Dutch Republic stood on the side of Austria, together with Great Britain and Russia, fighting against France, Prussia, Spain and Bavaria. During the 1748 peace negotiations, Great Britain and France appeared to lead; they could dictate the outcomes, such as Austria’s loss of Silesia.Footnote11

In 1748, the Dutch Republic had eight long-running newspapers in the Dutch language. They were published in the Holland cities of Amsterdam, Haarlem, Leiden, The Hague, Delft and Rotterdam,Footnote12 and, outside the province of Holland, in the cities of Utrecht and Groningen.Footnote13 None of the 1748 Dutch newspapers was yet a daily. However, by taking their different publication schemes into account, it becomes clear that newspaper issues were published in the Republic on all working days. The Hague, Leiden and Utrecht newspapers appeared on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays; the Amsterdam, Haarlem, Rotterdam and Delft newspapers on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays; and the Groningen newspaper only on Tuesdays and Fridays.

Although postal services and transportation between Dutch cities functioned exceptionally well by eighteenth-century European standards, it took at least a few hours from the publication of a newspaper issue before that issue could reach the nearest competitor’s desk. This meant that it was impossible to copy news items from Dutch newspapers and publish those items in other Dutch newspapers that appeared at the same day, and on most occasions also the next day. This also implies that when, for instance, the Friday and Saturday issues of different newspapers contained almost exactly the same news content about a topic, those items were derived from the same sources or news suppliers.

Having the advantages of a Monday issue and publication nearby the Republic’s governmental bodies, the ‘s Gravenhaegse Courant (The Hague Newspaper) was the first Dutch newspaper to mention the conclusion of peace, in a ‘P[ost] S[criptum]’ in its October 21, 1748 issue. On the previous day, between 6 and 7 pm, Major-General Charles Sturier, coming from Aix-la-Chapelle, had informed the Dutch States General and Stadtholder William IV that peace had been concluded on Friday the 18th at 2 pm. The Rotterdamse Courant (Rotterdam Newspaper) published the same information in its October 22 issue, yet without the name of the major-general.

The detailed description of the courier and his entourage in the Hague newspaper, perhaps coming from an eyewitness who had seen them, suggests accuracy. However, the October 23 issue of the ‘s Gravenhaegse Courant rectified the messenger’s name. Not Sturier but Hendrik Tulleken had brought the ‘cheerful news’.Footnote14 Corrections of this kind and also the mentioning of not only dates but even hours of specific events are obvious indications that newspaper editors were aware of the fact that they had to publish precise information. This was perhaps the reason why the Rotterdam editor left out Sturier’s name, because he was not sure about it. Making too many mistakes in comparison with competitors could lead to loss of prestige and sales.Footnote15 On the other hand, newspaper readers were familiar with differences and inconsistencies between news reports. Intelligent readers knew that many news items were based on hearsay and non-official statements.Footnote16

The newspapers’ confusion about when the Peace had been signed is another example of inconsistencies as a result of editors’ hastiness or incorrect sources. Several Dutch newspapers mentioned the same time as the ‘s Gravenhaegse Courant, while a few competitors stated that the Peace had been concluded between October 17 and 18, at midnight. The October 24 Haarlem newspaper implicitly clarified the confusion about the time. Although everything had been arranged for signing the treaty during the night, the ceremony had been postponed due to the illness of the French plenipotentiary. The next afternoon the English and Dutch representatives had visited their French colleague, who had signed while lying in his bed. The Opregte Groninger Courant (Sincere Groningen Newspaper) did not yet treat the Peace in her October 22 edition, but did so in the subsequent October 25 issue. This demonstrates that it took more time to send tidings from Aix-la-Chapelle to Groningen than to the western part of the country.

Although the final treaty text of Aix-la-Chapelle was not yet known at the end of October, Dutch newspapers could by then publish an abstract of the preamble and 24 articles. The newspapers of The Hague and Leiden were the first Dutch newspapers with this information, published in their October 25 editions. The Hague editor included all articles, using for this nearly half of the edition’s two pages. The Leiden editor made a smaller selection. The Amsterdam, Haarlem, Rotterdam and Delft newspapers, however, published the same selection of articles as the ‘s Gravenhaegse Courant in their October 26 editions, as did the Groningen newspaper on October 29.Footnote17

By contrast to news digests, in which many extensive documents were included, the publication of long texts such as the provisional 1748 treaty was rather exceptional for newspapers of the time. This restricted the inclusion of many other news items, since it was unusual to extend eighteenth-century newspapers with additional pages. On some occasions long documents gave rise to an extraordinary edition published between ordinary issues, which was only possible, of course, when printers’ capacities were sufficient. The fact that most Dutch newspaper editors decided to include the provisional treaty text in their ordinary editions underlines the topic’s importance. They undoubtedly satisfied their readers’ curiosity about the agreements, which were crucial for Europe’s political future.

In addition, the author quoted in the ‘s Gravenhaegse Courant assured readers that his summary of the provisional treaty was truthful. This suggests that he had been able to obtain leaked documentation. The Hague editor published the information under the heading of the Netherlands with his own city in the dateline, which is an indication that he had acquired the treaty in his own city. The Leiden editor, however, published the articles under the heading of Germany, with Aix-la-Chapelle in the dateline. This suggests that he had received his information directly from a correspondent on the spot. It is noteworthy that the Leiden editor also introduced his selection with the affirmation that it was derived from a reliable source. All such phrases indicate that correspondents and editors thought it necessary to convince readers of the truthfulness of their news.

The exchange of the ratified final treaty documents happened earlier than the October 24 Delft newspaper had expected: on the morning of November 18, notably in silence.Footnote18 It was reported in the Dutch newspapers between November 22 and 26, 1748. In this case, the Leydse Courant was the first newspaper to mention the event, thus not The Hague’s newspaper. The author of the news message considered it truthful since it was also reported that all involved delegates would leave the city on November 19 or 20—in other words, the exchange had taken place. Most newspapers added that the meager ceremony had disappointed the city of Aix-la-Chapelle, which had decorated its city hall lavishly for this purpose, but all for nothing.Footnote19

From our present-day perspective, it is curious that several newspaper editions reporting the peace conclusion also included news items of earlier dates in which the signing of the peace was not yet at stake. Eighteenth-century newspaper readers, however, were used to such inconsistencies, which were difficult to avoid in the managing of a newspaper. Early modern newspapers were by definition collections of reports of events that had happened far away and weeks or months earlier, and of events from nearby that had happened a mere one or two days earlier.Footnote20

The 1748 Peace in Dutch News Digests

Being a monthly news digest, the Nederlandsche Jaerboeken (Dutch Annuals) was one of the first Dutch news periodicals of the time to pay attention to the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, in its November 1748 issue.Footnote21 This news digest was a project of the Amsterdam Mennonite publisher Frans Houttuyn. He had started his annals in the previous year, with the aim of focusing on domestic news.Footnote22 Although the unknown editor—perhaps Houttuyn himself—classed most of the selected news items in sections with the geographical captions of Dutch provinces, in this case he opened the issue with the peace news directly after the specification of the publication’s month and year.Footnote23 This indicates that he regarded the topic as one belonging to a national framework, even exceeding in importance compared to the other news from the States General—items that he usually classed under the section of Holland.

After a short introduction the editor prefaced his reflections on the Peace by first referring to several documents resulting from the negotiations. He quoted, for instance, a text that the envoys of France, Great Britain and the Dutch Republic had secretly signed in Aix-la-Chapelle on April 30, 1748.Footnote24 Readers of the Nederlandsche Jaerboeken—and many other news digests—could easily follow the editor’s introductory and concluding remarks since they were published in a larger font than the documents.Footnote25 Only after five documents, the publication of which required almost 10 pages (in great octavo), did the editor reach October 18, the day on which the final peace treaty had been signed. He did not present details about the procedures, the details of which had already been published in the newspapers, but immediately continued with the content of the final treaty, published over the next 18 pages. Subsequently he concluded his article, with several additional documents from other involved belligerents.Footnote26

With the publication of relevant documents the editor hoped to bring his audience to understand why the negotiations had taken so long. Furthermore, he expected that the documents could function as a model for ‘posterity’.Footnote27 This means that he considered his news digest as a medium of longer-lasting value than newspapers, and as perhaps comparable to the Europische Mercurius. He did not mention, however, that in order to survey events chronologically, posterity should combine these documents with documents that the news digest had already published earlier.Footnote28 Although the November issue gives the impression that the editor had waited with the publication of several texts in order to present an overview, his working method seems to have been less well considered and systematic than he pretended in his editorial remarks. Just as with newspaper editors, he appears to have had the journalistic attitude of publishing information as soon as possible after he had gathered it. In any event, the editor concluded his commentary with a sentence about the exchange of the ratified texts in the night of November 16 and 17, instead of on the morning of November 18, as had been mentioned in the newspapers.Footnote29

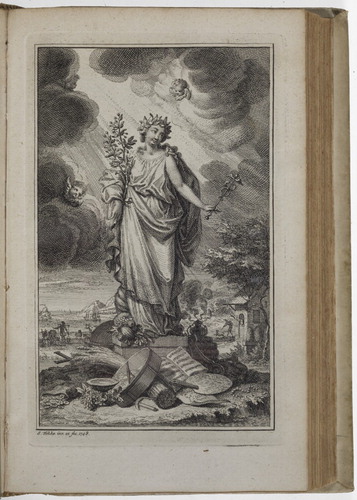

A second difference with Dutch newspapers was the insertion of a long ‘vredezang’ (peace song) and an engraving with the goddess of Peace as the central figure, made by the Amsterdam engraver Simon Fokke ().Footnote30 The editor hoped to please his audience with the anonymously published poem, which he said had been sent to him—an interesting indication of reader participation, which the Nederlandsche Jaerboeken much stimulated. Early modern Dutch newspapers sometimes included short poems related to topical events, but almost never had illustrations since their production time was too short to allow for this. The Nederlandsche Jaerboeken rarely published illustrations, which also indicates that its publisher wished to stress the importance of the news of the peace conclusion as a newsworthy event.

FIGURE 1 The Statue of Peace representing the 1748 Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, with objects below referring to a prospering economy, agriculture, arts and sciences during peace time. Engraving by Simon Fokke, published in Nederlandsche Jaerboeken 2 no. 2 (1748): between 1088–9. Copy University of Groningen Library (photograph Dirk Fennema, Haren, The Netherlands).

The information in the Nederlandsche Jaerboeken differed from the newspaper reports because this digest was mainly focused on the publication of documents with only short connecting remarks. This also applied to the monthly periodical De Groninger Nouvellist (The Groningen Chronicler), but to a lesser extent. The Groningen publisher Jacobus Sipkes and his editor Nathan Remkes had started this digest in 1745 with the aim of publishing political news and commentary that could not be printed in their Opregte Groninger Courant, since this newspaper was checked by the city government before publication.Footnote31 The result was a digest that was more critical than the Nederlandsche Jaerboeken, with more editorial information, and in which Remkes’ use of his own newspaper reports for this text was visible. The account about the conclusion of peace in the Opregte Groninger Courant of October 25, 1748, for instance, was almost identically worded in De Groninger Nouvellist of October 1748.Footnote32 In this issue, however, Remkes did not reproduce the preliminary 24 articles that had been published in his own and in other Dutch newspapers. He explained that he preferred to wait for the final treaty text. Since the articles as they had been hitherto published in the newspapers were not yet complete, he could not properly reflect on them.Footnote33 With such a remark he dissociated him from his own newspaper. Remkes kept his promise: the Groninger Nouvellist’s November issue was almost entirely filled with the text of the treaty, which, according to him, he had translated himself from the French original. In his commentary published in the following issue, he was rather skeptical of the treaty’s sustainability.Footnote34

De Europise Staats-secretaris (The European State Secretary) was another monthly periodical paying an appreciable amount of attention to the 1748 conclusion of peace. It had been published since 1741 by the Haarlem publishers Izaak and Johannes Enschede, who also managed the Oprechte Haerlemse Courant. They had started their news digest probably because they did not generate enough revenues from their newspaper in the first years after they had taken it over, in 1737.Footnote35 The combination of publishing both a newspaper and a news digest was not new in Haarlem, since the Enschedes’ predecessors Abraham Casteleyn and his wife Margaretha van Bancken had published both the Oprechte Haerlemse Courant and the Hollandsche Mercurius (Holland Mercury) in the period 1677–1690. It was, of course, attractive for publishers to generate money from collected news and documents that could not be included in their newspapers, or if they could at most in summarized forms.

In its October 1748 issue, De Europise Staats-secretaris discussed—in the section about Germany—several documents about the cumbersome diplomatic protocol that were intended to justify why the Aix-la-Chapelle negotiators had been so busy. The unknown editor commented cynically that the documents were poor excuses. Readers could find news about the announcement of the peace in The Hague in the editor’s monthly journal that he included under the heading of the United Netherlands. In the same item he described Johannes Enschede’s unconventional strategy for convincing the many incredulous Haarlem citizens that the peace had been signed on October 21. The publisher had exhibited four translucent illuminated ‘decorations’ painted by Frisian artist Taco Jelgersma at the entrance of his building, showing, among other things, symbols of liberty, peace and truth.Footnote36 He had organized this spectacle immediately after his fellow citizens had heard the peace news in their city in the morning, and thus the day before his next newspaper edition would be ready—a superb example of marketing the news locally. The paintings must already have been available, of course, probably in Enschede’s building or in the painter’s residence.

The news digest’s editor made impressive descriptions of the paintings for his readers. He explained that the mirror in one of the paintings should be seen as an allusion to ‘the diffusion of news regarding the current events by the weekly papers, and the recollection of the most important occurrences by the Monthly [sic] Europise Staats Secretaris’—an artificial interpretation that smacks of immodest self-fashioning. Unlike the Nederlandsche Jaerboeken and the Groninger Nouvellist, Enschede’s digest published both the 24 preliminary articles (in October) and the text of the final treaty (in November).Footnote37 Overall, the Haarlem digest’s style was critical and ironical; it was, at any rate, no copy of the concise newspaper accounts.

Since the Europische Mercurius was published only twice a year, readers had to wait until March 1749 before they could buy the volume in which the 1748 conclusion of peace news was reported.Footnote38 Its editor, indicated on this news digest’s title page only by the initials A. L., opened his October 1748 section with the news about Aix-la-Chapelle under the heading of Germany.Footnote39 It contains an orderly story of one page (in quarto) about what had happened in this city on October 18, without the confusion about the signature time as had been the case in the first newspaper reports. During the morning the English and Dutch representatives had deliberated with the ‘nauseous’ French representative. They had also spoken with Austria’s representative, before returning to the French envoy, who could not visit the Dutch residence because of his illness. All signatures had been obtained before 3 pm, after which couriers had been sent to the cities of Fontainebleau, Hanover, The Hague, London and Berlin. The Dutch delegation had offered a dinner to all persons involved.Footnote40

This summary was not much different from the information that the newspapers had earlier offered in fragmentary form. Nevertheless, a few differences from the newspaper reports emerge when we compare them with the European Mercury’s other pages related to the peace conclusion. The first is that the digest opens the account with an introduction in which the editor praises God extensively. The Almighty had helped the Dutch population, which had lost no grain of sand of its territory. With these words the author implicitly referred to the 1747 French invasion in the Dutch Republic that had been reversed in the peace treaty. They illustrate the digest’s reflexive character.

A second difference concerns a date mistake in the digest. Just as some newspaper reports had done before, the Mercury’s editor combined the announcement of the peace treaty with the preceding topic about the celebration of the Empress’ Name Day. However, he mentions the date of October 13. In this case, the newspapers had been correct in mentioning October 15 as Maria Theresa’s Name Day.Footnote41 This mistake makes clear that the news digests’ information was not necessarily better than the rapidly produced content of newspapers.

Also different from the newspapers is the Mercury’s continuation, with the publication of a protest against the conclusion of peace by James the Pretender, the son of the deposed King of England and Scotland James II. According to the Mercury’s editor this protest had been utterly pointless.Footnote42 A fourth difference from the newspapers is the rather logical fact that the Mercury’s editor published the final peace treaty text, instead of the provisional 24 articles, which had not yet been available for the newspapers at the end of October.Footnote43 Finally, it has to be remarked that the Europische Mercurius also presented the exchange of the ratified texts as taking place in the night of November 16 and 17.Footnote44

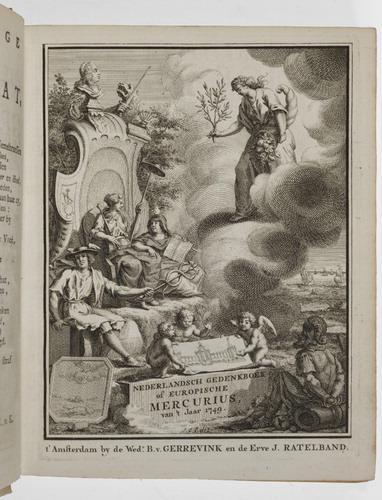

Although the Europische Mercurius often included illustrations, the second 1748 half-year volume did not have an engraving related to the conclusion of peace. Since the Mercury’s annual frontispiece was only reserved for the first half-year volumes, it was not possible to use this type of engraving for depicting the topic in the year of the peace conclusion itself. However, the Mercury’s 1749 frontispiece—made by Simon Fokke’s teacher Jan Caspar Philips—compensated for this, by showing the goddess of Peace offering bay leaves, on account of Aix-la-Chapelle (). She offered those leaves to Dutch Liberty, who had by then been sitting on her throne for a century, according to the rhyme that explained the frontispiece in the same volume. With this image the engraving also referred to the 1648 Peace of Münster, the centennial of which had been celebrated in 1748.

FIGURE 2 Frontispiece of the 1749 Europische Mercurius volume, showing Dutch Liberty, who receives bay leaves from the goddess of Peace because of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. A few putti hold a picture of the building that was used for the fireworks in The Hague that celebrated the 1748 peace. Engraving by Jan Caspar Philips. Copy University of Groningen Library (photograph Dirk Fennema, Haren, The Netherlands).

The allegorical character of the two engravings mentioned above demonstrates that early modern artists were challenged to depict abstract notions such as peace and prosperity. Educated contemporaries were familiar with the images that represented such news topics. They could also buy such news prints separately. In December 1748, for instance, publisher Pieter Schenk announced in the newspapers the sale of the imaginative engraving allegorizing on the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle made by Pieter van den Berge.Footnote45

News Digests between Newspapers and Historiography

Newspapers have always been disposable items, not easy to store in paper format. Whoever wanted to acquaint himself with recent history would need to turn to the much more convenient genre of news digests. Digests had the format of books that could be easily preserved in libraries on shelves. Because of this simple reason alone, they were more suitable than newspapers for reading old news reports. This also explains why we can retrieve advertisements for old copies of news digests—as mentioned in this article’s introduction—but never for old series of newspapers. Moreover, most digests’ editors could manage the news better than newspapermen by making good summaries without the mistakes resulting from incorrect, early rumors, and by including indices in their works, which helped readers to locate information.

In short, news digests gave a second life to old news reports, storing them for later generations. For this next life the reports were re-edited using the latest state of affairs and knowledge. The 1748 case shows that in digests, newspapers’ mistakes and false rumors were removed as far as possible, while newly available documents were added. Nevertheless, this re-editing process did not yet give news digests the status of proper history. They remained bound to the relatively short periods about which they reported. In internationally oriented Dutch digests, the news was presented in the same layout as in most newspapers: under the names of the states with which they were connected. Moreover, digests still dealt with many contemporary topics for which the outcomes were not yet clear. It is true that they reflected on the news with more distance than newspapers did, albeit with less distance than the audience could expect in historiographical material. They also had shortcomings.

The position of news digests between newspapers and historiography can be illustrated by the attitude of digests’ editors towards newspapers. Although editors must have used them extensively for making their summaries, they did not explicitly refer to newspaper reports in their accounts, and pretended to have made their own syntheses. Aside from the genre’s conventions concerning explanation of sources, a plausible reason why the editors preferred not to mention newspapers as a source might be that they wished to uphold the notion that their work was of better quality than the newspapers.

However, the results of a simple search action in the digitized Europische Mercurius volumes of the late 1740s with the Dutch words ‘courant’ and ‘couranten’ (coranto[s] or newspaper[s]) confirm that digests’ editors did not completely ignore newspapers in their accounts. In his 1747 volume, for instance, the European Mercury’s editor presents a story in which phrases from a news item in the Leydse Courant are quoted.Footnote46 Furthermore, the 1748 volume includes corrections to a false message printed in many Dutch newspapers, which the digest’s editor states had been published in the ‘s Gravenhaegse Courant by order of Stadtholder William IV.Footnote47

A date mistake in the 1749 volume of the Europische Mercurius almost surely reveals that this digest’s editor really used newspaper reports as sources for his own summaries. The inaccuracy concerns the date of the fireworks organized in The Hague to celebrate the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, in June 1749. The digest mentions the date of June 17, while the fireworks had taken place on June 13, a date that readers even could find in the caption on the engraving on the foldout next to one of the digest’s subsequent pages.Footnote48 Several Dutch newspapers—those of Amsterdam, Haarlem, Delft and Groningen—had reported on the June 13 fireworks in their issues of June 17. It seems quite reasonable that the digest’s editor confused the dates when he consulted one of those newspapers.Footnote49

It is also fairly certain that the news digest editors used foreign newspapers. The same search actions with the key words ‘courant’ and ‘couranten’ in the 1740s Europische Mercurius’ volumes, and also with the Dutch key words ‘papier’ (paper) and ‘papieren’ (papers), give rise to this idea. In his 1741 volume, for example, the digest’s editor quotes—although without presenting the exact titles—the English ‘Nieus-Papieren’ (Newspapers), which would have printed the English proverb ‘a strong attack is half the battle won’ within reports about rumors that England would be soon at war with France.Footnote50 In 1746, the editor quoted a long passage from ‘de Fransche Courant van Parys’ (the French newspaper of Paris), yet again without giving its French title.Footnote51 On a few occasions he used even more vague words such as ‘publicque buitenlandsche Nieus-Papieren’ (public foreign Newspapers) in his introductions to accounts or documents.Footnote52 Mentioning foreign newspapers as a source may have been a method to impress readers. With politically sensitive information, it could also be a way to avoid problems with the authorities. Editors implicitly defended themselves by showing that they had retrieved their information from public sources.

In his account about the course of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1743, the Europische Mercurius editor recalled that the ‘Courant der Stadt Parys’ (the Newspaper of the City of Paris) had wrongly credited a victory to the French army on orders of the French court, although the Allied Forces had been victorious.Footnote53 In this case, it is uncertain whether he had derived the news directly from the Parisian newspaper or from another source, such as a possible newsletter from a correspondent. Nevertheless, it is a nice example of contemporary reflection on the functioning of the early modern newspapers, in which governments tried to interfere for their own benefit. The clear message was: do not immediately believe what the enemy’s newspapers tell. At the same time, news digest editors positioned their digests as accurate and potential sources for historical writing.

The prominent Amsterdam historian Jan Wagenaar (1709–1773) was one of the eighteenth-century authors who frequently mentioned the Europische Mercurius in his notes. Although he did not refer to this news digest in his pages about the 1748 peace in the 20th volume of his Vaderlandsche Historie (National History),Footnote54 he cited the Mercury in the same volume concerning other topics,Footnote55 and so did the historians who published additions to this volume at the end of the eighteenth century.Footnote56 Leo Wessels counted 185 references to the Europische Mercurius in Wagenaar’s multivolumed Vaderlandsche Historie. Wagenaar would have particularly appreciated the Europische Mercurius because of its abundance of ‘real’ documents.Footnote57

Historian and numismatist Gerard van Loon (1683–1758) was another Dutch author who frequently used the Europische Mercurius as a source, citing it for instance nearly 1400 times in the fourth volume of his Beschryving der Nederlandsche historipenningen (Description of the Dutch history medals). Although Van Loon also lavishly referred to many other sources in this volume, which dealt with the period 1691–1716 and was published in 1731, this work shows that he regarded the Europische Mercurius as the most suitable source to put the medals in their—at that time, relatively recent—historical context. The jurist Pieter Boddaert (1694–1760) is an excellent example of a chronicler who referred to the Europische Mercurius because of its information about the Peace of 1748.Footnote58 He did so in a volume of his Hedendaagsche historie (Contemporary History) that was published in 1753, so, only a few years after the Mercury had been published.

Final Remarks

The 1748 case treated in this article demonstrates that newspapers can be considered as a preliminary and news digests as a subsequent step in writing history. They show the different ways news was managed in early modern news media. The first category provided factual information ordered according to chronological principles, yet also including mistakes and rumors due to uncertainties and incorrect sources. Editors of the second category could avoid such failures—in which they not completely succeeded—and had more opportunities to put facts in perspective by providing commentary or critical remarks, and by including all kinds of documents. They could also take the liberty to write cynically, ironically and humorously, at least within the permissible boundaries. As regards the four news digests discussed above, this was most visible in De Europise Staats-secretaris, but the critical Groninger Nouvellist also proved to be a digest with a unique character.

A specific style was, of course, only one of the means that news digests’ editors and publishers employed to attract readers. They also tried to make their mark by factors such as formats, layout, frequency and prices. Another distinctive feature was that news digests had the possibility to reflect on the news by including prints, which, in many occasions, were allegorical representations made by professionals, as has been demonstrated by the engravings in the Nederlandsche Jaerboeken and in the Europische Mercurius.

Since readers collected news digests in series, these media became—in contrast to newspapers and pamphlets—suitable sources for contemporary historians who wished to make references in their works to descriptions of relevant events and corresponding documents. The examples mentioned above suggest that of all the available Dutch news digests, historians considered the Europische Mercurius the most valuable or appropriate source for their references. This is not surprising, since the other digests were new in the 1740s. They lacked the Mercury’s wide circulation and its strong reputation of reliability and sustainability, features which the Mercury had acquired over a period of several decades.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joop W. Koopmans

Joop W. Koopmans, History Department, Oude Kijk in 't Jatstraat 26, 9712 EK, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Notes

1. The Europische Mercurius (EM) existed since 1690. In 1740, its name was changed to Nederlandsch gedenkboek of Europische Mercurius. As this news digest is best known under its original name, I will also use Europische Mercurius for volumes printed from 1740 onwards. On the EM: Koopmans, “Storehouses,” 262–4. For comments, I am grateful to Megan Williams.

2. Leydse Courant (LeyC; Leiden Newspaper), August 10, 1744; Amsterdamse Courant (AmC; Amsterdam Newspaper), August 13, 1744. For this article, most newspaper issues have been retrieved from the Dutch Royal Library site www.delpher.nl.

3. Oprechte Haerlemse Courant (OHC; Sincere Haarlem Newspaper), February 20, 23 and 25, 1745.

4. See EM 56, no. 1 (1745): 91–2 and 109–16.

5. E.g. AmC and OHC, January 30, 1745.

6. This was the case until the 1780s. Broersma, “Constructing”; Pettegree, The Invention, 12, 313–4.

7. Recent publications about news networks and the gathering of news are, e.g. Raymond and Moxham, News Networks; Arblaster, From Ghent.

8. Cf. Bellingradt, “Periodische Zeitung.”

9. E.g. Haks, Vaderland, 45, 156–7, 176, 196–7, 224, 294.

10. Tschopp, “Wie aus Nachrichten”; Raymond, The Invention, 269–313.

11. Duchhardt, “Die Niederlande”; Anderson, The War; and Browning, The War.

12. For this case, copies of the Rotterdamse Courant (RoC) that are present in Stadsarchief Rotterdam have been used, as they were not available via www.delpher.nl.

13. Schneider and Hemels, De Nederlandse krant, 51–4.

14. Tulleken’s (or ‘Tulkens’) name could already have been found in the October 22 issues of OHC and the city of Delft’s newspaper Hollandsche Historische Courant (HHC; Holland Historical Newspaper).

15. Cf. Michiel van Groesen’s article in this issue.

16. Broersma, “A Daily Truth.”

17. The Utrechtse Courant (UC; Utrecht Newspaper) did not publish any articles at all. The site www.delpher.nl only includes UC, October 21, 23 and 25 issues. Other October and November 1748 issues of this newspaper have been consulted in Het Utrechts Archief.

18. HHC, October 24, had expected that ratification of the peace treaty would be ready by the end of the year, when the centennial of the Peace of Westphalia (1648) would also be celebrated.

19. RoC and OHC, both November 23 and 26, 1748; UC, November 25, 1748; ’s Gravenhaegse Courant (’sGC), November 25 and 27, 1748; Opregte Groninger Courant (OGrC), AmC and HHC, November 26, 1748.

20. See, e.g. Koopmans, “Supply.”

21. I have not yet been able to find advertisements for this issue in newspapers, but the previous (October) issue was announced (in ’sGC, November 1, 1748) as available on November 4, 1748. This suggests a fast production scheme at that moment, though this was not always the case.

22. Nederlandsche Jaerboeken (NJ) 1, no. 1 (1747): “Voorbericht” (Introduction); Sprunger, “Frans Houttuyn.” Thanks to Rietje van Vliet for consulting her entry about this periodical, to be published in Encyclopedie Nederlandstalige tijdschriften (https://ent1815.wordpress.com/).

23. NJ 2, no. 2 (1748): 1055.

24. Ibid., 1055–6.

25. Quotes within the editor’s text were made visible with a quotation mark at the beginning of each line of the quote.

26. Ibid., 1065–81. Readers were not solely dependent on the news media for the Dutch version of the final peace treaty text, since this document had also been published separately by the Middelburg printer Anthony de Winter. Its Dutch title: Generale en definitive vreedetractaat gesloten tot Aaken den 18 October 1748 tussen de volgende mogentheden. Other Dutch (news) pamphlets about the conclusion of peace—except for several commemorative poems (e.g. of J. Lagendaals, G. Muyser and G. Toon)—are thus far unknown.

27. Ibid., 1058–9.

28. See, e.g. the July issue of NJ 2, no. 2 (1748): 575–83.

29. Ibid., 1081–5.

30. Ibid., 1085–9; Buijnsters-Smets, “Simon Fokke (1712–1784),” 132, 136–7; see also http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.214524. In 1749 Simon Fokke made another allegorical engraving concerning the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle: http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.214529.

31. Moes, “Politique Reflexien.”

32. OGrC, October 25, 1748; De Groninger Nouvellist (DGN) (1748): 466.

33. DGN (1748): 470.

34. Ibid., 560–96.

35. From 1743 the Haarlem newspaper seems to have been profitable again. Couvée, “The Administration,” 91–4.

36. The “Decoratien”—their fate is unclear—also showed busts of the Orange-Nassau stadtholders and the local heroine Kenau Simons Hasselaar, and the coat of arms of the belligerent countries. According to the Netherlands Institute for Art History (https://rkd.nl/explore/artists/42149), Taco Hayo (or Tako Hajo) Jelgersma (from Harlingen; 1702–1795) was active in Haarlem from 1752 (when he joined the Guild of St. Luke). This news account seems to confirm that he was already working in this city at least in 1748.

37. De Europise Staats-secretaris (1748): 1123–31, 1202, 1204–16, 1274–1307 (in octavo). Used (rare) copy: Noord-Hollands Archief in Haarlem, the Netherlands.

38. This volume was announced in AmC, March 8, 1749.

39. A. L. may have been Abraham George Luiscius, a lawyer and Dutch envoy in Prussia. Luiscius published the Algemeen historisch, geographisch en genealogisch woordenboek (8 vols.; General historical, geographical and geneaological dictionary; 1724–1737), which indicates that he was capable of also composing a news digest. Thanks to Kees van Strien for this suggestion.

40. EM 59, no. 2 (1748): 222.

41. Cf. EM 59, no. 2 (1748): 220, and, e.g. AmC, OHC and OGrC, October 22, 1748. October 15, was also reported in other Dutch newspapers, e.g. ’sGC, October 9, 1748 and LeyC, October 11, 1748.

42. EM 59, no. 2 (1748): 221. This protest had also been published in the periodical Groningen Nouvellist of 1748 (announcement of this issue in OGrC, October 1 and 4, 1748).

43. EM 59, no. 2 (1748): 222–38.

44. Ibid., 268.

45. http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.482109 (announced in, e.g. LeyC, December 18, 1748).

46. EM 58, no. 1(1747): 201. Cf. LeyC, May 1, 1747.

47. EM 59, no. 1 (1748): 282–3. Cf. ’sGC, May 24, 1748. This correction was also published in AmC, HHC and OHC, May 25, 1748, and LeyC, May 31, 1748. The Leiden newspaper is mentioned again in the digest’s 1750 volume, in this case because of an advertisement from the city of Leeuwarden concerning a competition about stimulating science and the arts in the Republic. EM 61, no. 2 (1750): 234. Cf. LeyC, July 1, 1750. Other issues in which Dutch newspapers are mentioned in EM 59, no. 1 (1748): 297–9 and ibid. 60, no. 2 (1749): 160.

48. EM 60, no. 1(1749): 285 and foldout next to 292.

49. The newspapers of The Hague and Leiden reported about the fireworks in the June 16, 1749 issue.

50. EM 52, no. 2 (1741): 101. Other references to the English newspapers: ibid. no. 2: 218–9; ibid. 53, no. 2 (1742): 100–3; ibid. 54, no. 1 (1743): 278 and no. 22, 199–200; ibid. 59, no. 2 (1748): 76.

51. Ibid. 56, no. 1(1746): 95–6.

52. See, e.g. ibid. 55, no. 2 (1744): 116; ibid. 56, no. 1 (1745): 56.

53. Ibid. 54, no. 2 (1743): 28.

54. In this case, Wagenaar referred to not indicated ‘real sources, documents and notes’, and he derived the treaty from Jean Rousset de Missy’s Recueil historique etc. Wagenaar, Vaderlandsche Historie, vol. 20: 244, 251.

55. Ibid., 12, 18. About Wagenaar and his work: Wessels, Bron.

56. Van Wijn (e.a.), Byvoegsels, 35, 39, 40, 82, 107.

57. The EM was one of 15 periodicals in Wagenaar’s library. Wessels, Bron, 169, 508.

58. [Boddaert], Hedendaagsche historie, vol. 20, 113.

Bibliography

- Anderson, M. S. The War of the Austrian Succession, 1740–1748. London: Longman, 1995.

- Arblaster, P. From Ghent to Aix: How They Brought the News in the Habsburg Netherlands, 1550–1700. Leiden: Brill, 2014.

- Bellingradt, B. “Periodische Zeitung und akzidentielle Flugpublizistik: Zu den intertextuellen, interdependenten und intermedialen Momenten des frühneuzeitlichten Medienverbundes.” In Die Entstehung des Zeitungswesen im 17. Jahrhundert: Ein neues Medium und seine Folgen für das Kommunikationssystem der Frühen Neuzeit, edited by V. Bauer and H. Böning, 55–77. Bremen: edition lumière, 2011.

- [Boddaert, P.], Hedendaagsche historie, of tegenwoordige staat van alle volkeren etc., vol. 20. Amsterdam: Isaak Tirion, 1753.

- Broersma, M. “Constructing Public Opinion: Dutch Newspapers on the Eve of a Revolution (1780–1795).” In News and Politics in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800), edited by J. W. Koopmans, 219–235. Leuven: Peeters, 2005.

- Broersma, M. “A Daily Truth: The Persuasive Power of Early Modern Newspapers.” In Commonplace Culture in Western Europe in the Early Modern Period III: Legitimation of Authority, edited by J. W. Koopmans and N. H. Petersen, 19–34. Leuven: Peeters, 2011.

- Browning, R. The War of the Austrian Succession. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1993.

- Buijnsters-Smets, L. “Simon Fokke (1712–1784) als boekillustrator.” Leids Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 4 (1985): 127–146.

- Couvée, D. H. “The Administration of the ‘Oprechte Haarlemse Courant’ 1738–1742.” Gazette: International Journal of the Science of the Press4 (1958): 91–110.

- De Europische Staats-secretaris etc. (Haarlem: Izaäk and Joh. Enschede, 1748).

- De Groninger Nouvellist (Groningen: Jacobus Sipkes, 1748).

- Duchhardt, H. “Die Niederlande und der Aachener Friede (1748).” In Tussen Munster & Aken. De Nederlandse Republiek als grote mogendheid (1648–1748), edited by S. Groenveld, M. Ebben, and R. Fagel, 67–73. Maastricht: Shaker, 2005.

- Haks, D., Vaderland en vrede 1672–1713: Publiciteit over de Nederlandse Republiek in oorlog. Hilversum: Verloren, 2013.

- Koopmans, J. W. “Supply and Speed of Foreign News to the Netherlands During the Eighteenth Century: A Comparison of Newspapers in Haarlem and Groningen.” In News and Politics in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800), edited by J. W. Koopmans, 185–201. Leuven: Peeters, 2005.

- Koopmans, J. W. “Storehouses of News: The Meaning of Early Modern News Periodicals in Western Europe.” In Not Dead Things: The Dissemination of Popular Print in England and Wales, Italy, and the Low Countries, 1500–1820, edited by R. Harms, J. Raymond, and J. Salman, 253–273. Leiden: Brill, 2013.

- Loon, G. van. Beschryving der Nederlandsche historipenningen etc. Vol. 4. The Hague: Christiaan van Lom, Pieter Gosse en Pieter de Hondt, 1731.

- Moes, H. J. “‘Politique Reflexien en vrye gedagten’ in de stad Groningen: De politieke pers in de 18e eeuw.” Historisch Jaarboek Groningen 2005, 7–25.

- Nederlandsch gedenkboek of Europische Mercurius 52–61 (Amsterdam: B. van Gerrrevink and Heirs J. Ratelband, 1741–1750 ).

- Nederlandsche Jaerboeken 2 (Amsterdam: F. Houttuyn, 1748 ).

- Pettegree, A. The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know about Itself. London: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Raymond, J. The Invention of the Newspaper: English Newsbooks 1641–1649. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2005.

- Raymond, J., and N. Moxham, eds. News Networks in Early Modern Europe. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

- Schneider, M., and J. Hemels. De Nederlandse krant: Van ‘nieuwstydinghe’ tot dagblad. 4th ed. Baarn: Het Wereldvenster, 1979.

- Sprunger, K. L., “Frans Houttuyn, Amsterdam Bookseller: Preaching, Publishing and the Mennonite Enlightenment.” Mennonite Quarterly Review 78 (2004): 165–184.

- Tschopp, S. S. “Wie aus Nachrichten Geschichte wird: Die Bedeutung publizistischer Quellen für die Augsburger Chronik des Georg Kölderer.” In Consuming News: Newspapers and Print Culture in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800), edited by G. Scholz Williams and W. Layher, 33–78. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2008 [Daphnis 37, no. 1–2 (2008)].

- Wagenaar, Jan. Vaderlandsche Historie, vervattende de Geschiedenissen der Vereenigde Nederlanden, inzonderheid die van Holland. Vol. 20, 2nd ed. Amsterdam: Wed. Isaak Tirion, 1770.

- Wessels, L. H. M. Bron, waarheid en de verandering der tijden: Jan Wagenaar (1709–1773), een historiografische studie. The Hague: Stichting Hollandse Historische Reeks, 1997.

- Wijn, H. van (e.a.). Byvoegsels en aanmerkingen voor het twintigste deel der Vaderlandsche historie van Jan Wagenaar. Amsterdam: Johannes Allart, 1796.