Abstract

This article analyses the transnational production processes of foreign correspondence in the Cold War. It examines the double role of foreign correspondents as reporters and Cold War political agents. Recent scholarship has explored the activities of Western correspondents reporting from the Communist world. Little is known, however, about Eastern bloc correspondents in the West. Drawing on the rarely studied files on East German foreign correspondents held by the Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv, the article problematizes the image of GDR journalists as obedient intelligence officers and highlights the dilemmas of journalists deployed to defend national interests. Focusing on the Nordic countries in the mid1970s, the article provides detailed insights into the politics and practices of East German foreign correspondence before the digital revolution. The article thus shows the benefits of going beyond the traditional focus on media content to analyse the daily practices as well as the political and symbolic significance of journalism. It contributes to the growing historical research on foreign correspondents and the media in East Germany and beyond.

Introduction

Before the digital era, foreign correspondents provided a rare source of information about current affairs in faraway places. This gave the correspondents a significance that went far beyond the sphere of journalism and the media. Footnote1 Rulers, politicians, and businessmen used foreign news for political and economic gains. Foreign correspondents could serve a variety of functions in international relations ranging from government couriers to intelligence and publicity agents who projected soft power abroad.Footnote2 Modern media practice has often been at odds with the ideal of the neutral Fourth Estate, and foreign news reporting has arguably been the most politicized field of journalism.Footnote3

The Cold War era of global superpower rivalry saw an intense politicization of journalism. Foreign correspondents reporting from enemy territory were often suspected of plotting and spying in collusion with diplomats and the secret services.Footnote4 Whether the suspicions were justified or not, they frequently resulted in the expulsion and in some cases the arrest of foreign correspondents. On several occasions, and early in the Cold War in particular, disputes over foreign correspondents escalated into full-scale diplomatic crises.Footnote5 In other cases, however, foreign correspondents provided a vital line of communication between countries that did not officially recognize each other.Footnote6 In the terminology of New Diplomatic History, foreign correspondents thus belonged to the category of individual, non-state actors, who challenged orthodox notions of who was a diplomat.Footnote7

Foreign correspondents also challenge the dominant national perspective in media history. Their life and work is transnational by definition. Bernard Cohen once described the correspondent who specialized in foreign affairs as ‘a cosmopolitan among cosmopolitans’.Footnote8 He (the foreign correspondent was almost always a man) communicated across national boundaries and between media systems. Foreign news reporting thus provides an excellent example of entangled media history. Although the nation-state dictates the overarching framework, the production, dissemination, and reception of foreign news reports cannot be fully understood without a transnational perspective.Footnote9

Much research on foreign correspondents has focused on the news content rather than on the daily practices and cultural significance of foreign correspondents.Footnote10 In the context of the Communist correspondents in the Cold War, we know little about the everyday journalistic work, tools, networks of colleagues and competitors, relations with the home office, and esprit de corps.Footnote11 In other words, the transnational production processes unique to foreign news reporting in the Cold War have barely been explored.

This article examines the politics and practices of foreign correspondents who reported from the West for East German television (first DFF, then renamed DDR-FS in 1972).Footnote12 It examines the dual role of East German reporters in the West as political agents and news reporters. The aim is to problematize the image of GDR journalists as little more than obedient intelligence officers, and highlight the journalists’ professional practices as they were simultaneously deployed as reporters and agents of the state. While the article concentrates on the Nordeuropa bureau, which covered the Nordic countries in the mid-1970s, the analysis also draws on sources from other bureaus in the West to provide detailed insights into the production of news by East German foreign correspondents, showing how they navigated security issues, language barriers, production norms, and technical challenges before the digital revolution.

Recent scholarship has explored the activities of Western correspondents, and in particular West German and American correspondents, who reported from the Communist world. Julia Metger and Dina Fainberg have analyzed the efforts of Western journalists to push back boundaries and question the official image of Soviet society under difficult working conditions.Footnote13 Rósa Magnúsdóttir has studied the role of US journalists as interpreters of Soviet society for a home audience.Footnote14 The particular challenges that faced West German journalists reporting from East Germany have been the subject of several studies.Footnote15 Finally, attitudes to West German journalists across Eastern Europe have also been outlined.Footnote16

In comparison, research on foreign correspondents who reported from the West for audiences in the Eastern bloc is thin on the ground. The authoritative history of the East German flagship news programme, Aktuelle Kamera (lit. current camera), barely touches on the subject of foreign correspondents.Footnote17 The history of the East German news agency, Allgemeine Deutsche Nachrichtendienst, provides some information about the beginnings and expansion of a network of foreign correspondents, especially in the 1940s and 1950s.Footnote18 Bernhard Gißibl has recently continued this line of research by showing how foreign correspondents served as ‘diplomats in disguise’ until the Basic Treaty (Grundlagenvertrag) of 1972 finally made it possible for the GDR to establish and maintain a regular corps of diplomats in Western countries.Footnote19 A recent oral history project to interview former German correspondents reporting from the ‘other side’ has complemented the archive-based research with lively stories and idiosyncratic analyses, though these are often coloured by the time that has passed.Footnote20

None of these studies, however, has engaged with the voluminous material on foreign correspondents held by Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv (DRA) in Potsdam. Through analyses of letters, reports, and policy documents pertaining to the foreign correspondent section of Aktuelle Kamera and especially files from the Nordeuropa bureau of DDR-FS, the analysis that follows provides detailed insights into the politics and practices of East Germany’s foreign correspondents.

The Politics of GDR Foreign Correspondence

Founded in 1949, the GDR was one of the Soviet Union’s most loyal allies in the Eastern bloc. In the West, however, East Germany long fought for formal recognition as a sovereign state. Under the Hallstein Doctrine, formulated in 1955, the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) viewed recognition of the GDR by another country as an unfriendly act towards the FRG.Footnote21 Thus, the East German state could not maintain official representation in NATO member states, and visits by East Germans to the NATO countries were deliberately obstructed. The issuing of entry visas to the West was handled by the Allied Travel Office in West Berlin, a remnant of the early post-war years kept in place to frustrate East Germany.Footnote22 Under these conditions it was difficult to maintain a network of foreign correspondents in the West. Local sympathizers with the GDR provided one solution.Footnote23 For example, a West German, Horst Schäfer, served as correspondent for the Berlin Pressebüro (bpb) in Munich for seventeen years until 1972 when the two German states finally reached an agreement of mutual recognition. During this time, Schäfer was frequently sent on short trips to other NATO member states since his citizenship permitted spontaneous missions.Footnote24

The leadership of the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED), the East German Communist Party, viewed the country’s foreign correspondents as an integrated part of the Foreign Service, who should serve the interests of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA).Footnote25 This official perception of Allgemeine Deutsche Nachrichtendienst (ADN) correspondents as journalists and diplomats was also mirrored in a 1982 thesis on the history of ADN, written at the GDR media school in Leipzig. The thesis claimed that prior to 1972, ADN bureaus and trade representations had served as bridgeheads in the struggle for recognition as ‘they helped prepare the establishing of diplomatic relations’.Footnote26 The politicization of the GDR foreign correspondent network was also evident from the MFA’s repeated requests to Deba Wieland, General Director of ADN, for the posting of additional foreign correspondents. In 1968 the deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, Wolfgang Kiesewetter, asked Wieland for a second correspondent at UN headquarters in New York. Two years later, Kiesewetter proposed the posting of a Central Africa correspondent to Brazzaville and another one to Nigeria given that country’s importance for GDR’s Africa policy. Wieland, however, responded tersely that human and financial resources were limited, so ‘correspondents must be posted rationally’ and in accordance with established political priorities.Footnote27 In other words, the head of ADN, which shouldered the considerable costs of the foreign correspondent network, was not prepared to concede to the whims of the MFA.

Following recognition, East German diplomats and journalists posted to the West enjoyed better access to long-stay visas and the professional circles of the diplomatic corps and press clubs. The East German leadership jumped at the opportunity to expand its presence abroad and assert itself on the international stage. The GDR quickly established a range of new diplomatic missions in the West. ADN bureaus in Belgium, the UK, France, and Italy, hitherto staffed by Western sympathizers or travelling correspondents, could now be operated by permanently posted East German citizens. New ADN bureaus opened in Portugal (1974) and Spain (1978), helping the increase in the total number of bureaus from 27 in 1968 to 41 in 1981.Footnote28

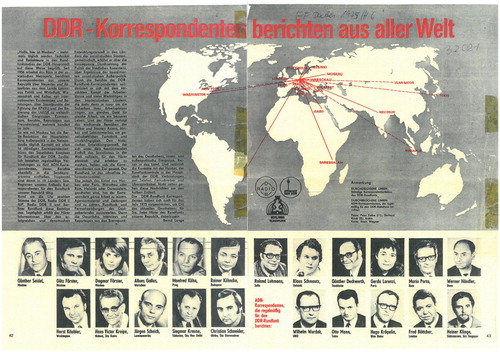

While the East German newswire had sent its first foreign correspondents abroad in the summer of 1948, DFF only started broadcasting in 1952. Its first years saw a good deal of experimentation with form and content, while it worked to overcome the myriad of technical problems that plagued early television everywhere.Footnote29 DFF opened its first studio abroad in Moscow in 1957, and in 1958 its first foreign correspondent was posted there.Footnote30 Additional bureaus soon opened in other Eastern bloc capitals, and after 1972 DDR-FS expanded its network of foreign correspondents to include Washington, Bonn, London, and Paris. According to one estimate, the number of DDR-FS foreign correspondents doubled between 1972 and 1975.Footnote31 The presence of East German reporters around the world was regularly subject to feature articles in the domestic press, illustrated to show the global reach of the GDR and the omnipresence of its media representatives ().Footnote32

The appointment of a journalist for a post abroad was a complex process that involved SED’s Central Committee, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the directors of the broadcaster.Footnote33 Only the most reliable East German journalists were posted to the West, and the screening procedure was so meticulous that throughout the Cold War no more than a dozen East German journalists defected to the West.Footnote34 The downside of the careful selection procedure, however, was the limited pool of qualified candidates to choose from. The first journalists recruited to the East German media in the late 1940s and early 1950s were mostly amateurs without formal training or practical experience. The key to a job in the media sector at that time was an impeccable anti-fascist stance, a working-class background, and no contacts with the West. Contemporary audiences and the SED-leadership often bemoaned the poor quality of early East German journalism; the strict recruitment criteria help explain the dissatisfaction.Footnote35 But by the 1960s, journalism was professionalized and the path to a career in the media was clearer: a high school diploma, military service, a media internship, and continued studies at the Leipzig media school, after which a party committee allocated the candidate a job in television, radio, or the press.Footnote36 Ideological conformism remained a key requirement for a successful career in journalism—as Michael Meyen and Anke Fiedler state in their collective biography of GDR journalists, ‘enemies of the system and people in opposition did not become journalists in the GDR’,Footnote37 and employees of the ‘Leitmedien’ (leading media) were generally conscious of working in the service of the state—and while membership of the SED was not a prerequisite for a media job, it certainly improved people’s career prospects. For aspiring foreign correspondents, it was essentially a requirement.Footnote38

Only the leading East German news media, ADN, the SED newspaper Neues Deutschland, and the Aktuelle Kamera television news programme could afford a proper network of foreign correspondents. These leading news media toed the official party line, and their editors were in daily contact with party and government officials.Footnote39 As one former Aktuelle Kamera foreign correspondent said, ‘what was broadcast by Aktuelle Kamera was to some extent also the official position of the GDR’.Footnote40 The Leitmedien signalled what was safe to report by other East German media.Footnote41 Only on marginal issues where there was no party line could journalists—foreign correspondents included—express themselves more freely. This meant that the overwhelming majority of news reports from abroad presented their content in a formulaic friend–enemy schemata.Footnote42 The overly politicized and predictable reporting of foreign affairs resulted in very low ratings for Aktuelle Kamera. Only between 5 and 10% of viewers watched it and the foreign reportage programme Objektiv.Footnote43

The history of East German foreign correspondence is however richer and more complex than the hackneyed propaganda it often resulted in. In the following analysis we thus look beyond the run-of-the-mill news content to the journalistic practices and the political work done by correspondents doubling as diplomats in disguise. As will be seen, the short-lived Nordeuropa bureau provides valuable insights into the life and work of these East–West transnational agents.

East German Correspondents and the Nordic Countries

Prior to its international recognition in 1972, the East German foreign office considered Europe’s neutral states to be the weakest links in the Western non-recognition alliance. Sweden, Finland, and Austria were therefore the preferred targets of its strategy of incrementally increasing the official character of non-state representation in the hope that the host country would implicitly end up recognizing the GDR.Footnote44 Sweden was a geographic neighbour, and a country with which the German-speaking areas had traditionally enjoyed close cultural and economic relations. Sweden had also distinguished itself by accepting East German passports early on.Footnote45 East German journalists could thus operate relatively unhindered in the country, and ADN opened a Stockholm office already in 1956.Footnote46 Sweden was also the testing ground for new East German initiatives towards the West. East Germany’s first tourist office in the West opened in Stockholm in 1956, cloaked as the information office of the East German railways.Footnote47 In February 1960, the office changed its name to Verkehrsvertretung der Deutschen Demokratischen Republik (Transport Agency of the German Democratic Republic). The new name caused West German dismay, and its ambassador in Stockholm protested that Sweden’s acceptance was a step toward official recognition of the GDR, and would set a precedent for other countries. It was not long before similarly named offices indeed opened in Copenhagen and Vienna.Footnote48 Sweden and Denmark was also chosen as primary targets when an East German radio broadcaster for international audiences, Radio Berlin International, started broadcasting in May 1959.Footnote49

The rapid expansion of the foreign correspondent network after 1972 included the opening of Aktuelle Kamera’s Nordeuropa bureau in Stockholm. The Nordic countries had hitherto been covered by the radio journalist Günter Deckwerth, but now the Aktuelle Kamera leadership made a point of intensifying contacts in the North. The bureau was established in Stockholm in January 1974. Over the course of nine days, the cameraman assigned to the new bureau and an assistant arranged furnished accommodation, obtained accreditation, and established contacts with the local press corps.

The correspondent appointed the head of the Nordeuropa bureau was Heinz Sachsenweger. Born in the early 1930s, Sachsenweger was a seasoned journalist who had spent most of the sixties working for Aktuelle Kamera’s home news desk in East Berlin. In 1968–9 he had been posted to the Warsaw bureau, of which he was head by the time of his transfer to Stockholm. Sachsenweger’s posting to Stockholm coincided with the financial crises of the mid-1970s and he revelled in the negative news. In the surviving clips from his stint in the Nordic countries, Sachsenweger appeared as a professional journalist with a firm grasp of the East German correspondent genre. In his pieces to camera, he railed against rising unemployment and soaring living costs in Denmark and Sweden. He lamented the closing of a factory when a multinational company moved abroad, and he empathized with the demonstrations and strikes against the falling standard of living of the working class.Footnote50 The camerawork underpinned the message of Western inferiority. Take one establishing shot of a public square in central Copenhagen, which was filmed early in the morning when the traffic was still light and thus comparable to the normal level of an East German city. According to an interview with Sachsenweger in the late 1990s, practical reasons dictated that they had to film this early in the morning, ‘but it’s correct, there was a lot I couldn’t show’.Footnote51

When reporting from the capitalist world there was little room for human interest stories. The entire focus was hard news about the systemic flaws of capitalism, aggressive militarism, and the occasional summit or state visit. Sachsenweger would like to have done a story about the Tivoli amusement park in Copenhagen, but he never even suggested it ‘since I already knew the answer. “No!” We couldn’t allow ourselves to do something that would stimulate wanderlust.’Footnote52 A former ADN foreign correspondent in Prague and Bonn, Ralf Bachmann, has recounted the difference in topics he covered in East and West. From Prague he could write about beer or a film, but in Bonn that was out of the question.Footnote53 At the same time, the alignment of foreign correspondence with the foreign policy objectives of the GDR could also result in less conflict-oriented news, as was the case with France. Given its status as one of the GDR’s strategic trade partners, reporting from France was far more friendly than from the West in general.Footnote54

The dual role of East Germany’s foreign correspondents as political agents and journalists meant that they did not just produce reports for broadcast. Some of the information they provided was considered so sensitive that it was only distributed to the highest-ranking ministers and party officials, the so-called ‘circle of 12’.Footnote55 The Aktuelle Kamera correspondents also submitted monthly reports for internal use answering a set list of questions about the latest developments in local politics and economics. Language could prove a barrier to the East German journalists who sometimes lacked proficiency in the local tongue. In Sachsenweger’s case, he admitted two months after his arrival that he did not yet understand much Swedish.Footnote56 When compiling his reports he thus relied not only on the local media, but drew also on his contacts among his fellow journalists, in various left-wing parties, and at the embassies. The general picture of Scandinavian society provided in the monthly reports did not deviate from the reports made for broadcast: the capitalist system was in crisis and dissatisfaction widespread. Since the monthly reports were also forwarded to the MFA and the Ministry of State Security (Stasi) they helped maintain the understanding among the party leadership and in state security circles that the East German model was superior to the crisis-ridden capitalist system.Footnote57

The monthly reports were not limited to local news. They also provided ample evidence of East Germany’s obsession with its image abroad. Considerable attention was given to the attitudes Sachsenweger encountered and people’s impressions of the GDR. Sweden in particular was a disappointment. Sachsenweger’s first monthly report described the Swedish attitude to the GDR as ‘cold’ (whereas the Finns were ‘friendly’).Footnote58 Later reports confirmed the antagonistic image of the East–West conflict. In June 1975 Sachsenweger drily noted that ‘in Sweden there are in fact still people who have not yet realized that the 1950s are over.’Footnote59 To his dismay, Swedish television broadcast the French–West German spy thriller The Defector (Lautlose Waffen/L’espion, Raoul Levy 1966) ‘reminiscent of the worst days of Cold War propaganda’.Footnote60 As Sachsenweger (correctly) pointed out, the film depicts daily life in the GDR as ‘dictated by fear, oppression, and persecution’. Given Swedes’ limited knowledge about the true state of affairs in the GDR, Sachsenweger worried that ‘many people will believe this inflammatory film of the worst kind’.Footnote61

The files from the Nordeuropa bureau also show the extent to which Sachsenweger acted as an informal diplomat. An everyday example of how journalism and the national interest could overlap was Sachsenweger’s first monthly report from Stockholm. After being denied permission to shoot a story at a state-owned Swedish steel factory, he noted that such an obstructive attitude should be kept careful track of at home. As he reckoned, it might come handy one day when dealing with a request from a Swedish journalist working in East Germany.Footnote62 Sachsenweger shared this understanding of foreign correspondence as an integral part of international diplomacy with his superiors and some of his colleagues—though not all. In 1984 the head of the Lisbon bureau complained to Berlin that his cameraman was not fully committed to the journalistic practices guiding foreign correspondence for Aktuelle Kamera. The cameraman had artistic ambitions and could not reconcile with the ‘short and to a certain extent stereotypical AK-reporting’.Footnote63 The cameraman was also accused of not sharing the work ethic central to the esprit de corps. ‘Don’t exaggerate the whole thing, we’re not at war here’, he was said to have complained.Footnote64 Whether these words were ever uttered or not, the quote indicates how the superiors in East Berlin wanted their foreign correspondents to understand their role in the world: as frontline soldiers in the cultural Cold War. The crews were expected to conduct themselves in line with the diplomatic requirements of formal GDR representatives. For instance, another employee at the Lisbon bureau was officially reprimanded for not attending the farewell ceremony of a Soviet correspondent.Footnote65

All foreign bureaus, whether East or West, were required to respect a strict security regime with multiple locks, hidden safes, and careful attention to who were allowed to visit the office.Footnote66 Burglary and theft nevertheless did occur, and the ensuing paperwork is often revealing of how the foreign correspondents practiced their craft.Footnote67 Occasionally it also reveals whether the journalists had internalized their role as combatants in the Cold War. In 1988, three employees of the Sofia bureau had completed an assignment in Greece and were driving towards Athens along the coast. It was late July and the journalists stopped to have a quick dip in the sea. While the car was out of sight, unknown burglars broke into their Lada and two other parked cars. The journalists immediately reported the incident to East Berlin and the list of stolen items indicates a relaxed approach to safety measures: a passport, a driving license, a Bulgarian ID card, accreditations for Greece and Bulgaria, 1000 DM, 250 USD, and 25,000 drachmae in cash, as well as a camera, and an expensive Seiko watch.Footnote68 The single-page report of the incident was strictly factual and without the slightest display of remorse. A week later, however, the severity of the incident had dawned on the correspondents. In a two-page letter of repentance directed to the editor in chief of Aktuelle Kamera, the cameraman admitted to having violated the code of conduct for GDR officials travelling abroad. The potential magnitude of the ‘political and moral damages’ was now clear to him. ‘If these documents end up in the wrong hands … their misuse can inflict political harm on the GDR and the People’s Republic of Bulgaria’.Footnote69 As these examples show, Sachsenweger’s concern for GDR’s international relations was not uniformly shared despite the thorough schooling of East German foreign correspondents.

When circumstances allowed, correspondents were in daily communication with an editor at home in Berlin. These telephone calls were to discuss technical and organizational issues such as news topics to be covered and broadcasting slots for produced material.Footnote70 The Aktuelle Kamera journalists sought to heighten the sense of immediacy of their stories by including temporal adverbs such as ‘yesterday’, ‘today’, and ‘tomorrow’. However, as Sachsenweger complained, this was next to impossible for the Nordeuropa bureau, as its stories were practically never broadcast on the day for which they were ordered.Footnote71 The omission of Stockholm from a feature in the media magazine FF-Dabei on the entire East German foreign correspondent network stoked the feeling of being ignored and provoked a written demand for an explanation.Footnote72 The exclusion of the Nordeuropa bureau came on top of a similar situation a few months earlier when Sachsenweger had also been kept out of the loop: an East German parliamentary delegation had visited Copenhagen, yet Sachsenweger only learned from Danish sources that a special television crew had been sent from East Berlin to cover the visit. ‘It would be better if we were to learn something like this from Berlin in the future. Then you don’t feel stupid when negotiating with the Danish embassy as Nordeuropa bureau.’Footnote73

Sachsenweger also lamented the poor logistics behind the transportation of film material to East Berlin. In the 1970s it was not yet possible to transmit material home via satellite; they had to be shipped to East Berlin before they could be broadcast. From many countries it was usually sent by airmail, preferably with the East German flag carrier Interflug to keep the price down. Unfortunately for Nordeuropa bureau, Interflug did not operate between Stockholm and East Berlin, so its film material was carried by SAS—and deliveries occasionally went missing. This cumbersome arrangement could be avoided, as Sachsenweger pointed out, because the East German railways operated a night train between Stockholm and East Berlin. If only the conductor were allowed to handle the material, this would provide a cheap and reliable solution. In fact, Sachsenweger had already proposed such an arrangement six years earlier when he was stationed in Warsaw. In August 1974 he was promised a solution, yet, as he concluded his report in January 1975, ‘to this day, nothing has happened’.Footnote74

The Cost–Benefit Balance of Foreign Correspondence

‘Foreign correspondents’, writes Ulf Hannerz, ‘are often quite costly’.Footnote75 Staff posted abroad need solid expense accounts to cover their frequent travels. The equipment and communication infrastructure required by television correspondents adds significantly to the costs. For a country like the GDR which struggled to balance its budget and secure hard currency, all expenses incurred in the West had to be monitored carefully. Since the early days of the GDR, the party leadership and the MFA were keen to enrol journalists as informal diplomats, and so expand the GDR’s presence abroad through its foreign correspondents. When new opportunities arose after the recognition of the GDR, its correspondent network grew exponentially. It was not long, however, before Aktuelle Kamera was in financial difficulties, and the Nordeuropa bureau was closed in the autumn of 1976, less than two years after Sachsenweger’s arrival in Stockholm.

The decision to cut back DDR-FS’s foreign correspondent network was not taken at random. The head of the foreign correspondent section, Siegfred Leske, kept meticulous track of each bureau’s productivity. The indicators included the number of reports produced, the number of reports broadcast, and the cost per broadcast minute. These figures, in combination with quality assessments of the reports submitted, comprised the performance data on which each bureau was evaluated. All bureaus competed in a ‘socialist competition’ that promised financial rewards for the best, most efficient journalists. Regular newsletters reminded the bureaus of their score and encouraged the utmost frugality. In 1977 the competition also began to factor in savings in the use of film stock.Footnote76 To keep expenses down, it was essential that what was shot on the costly film reels was of a quality that could be broadcast. The ADN correspondent Ralf Bachmann reminisced that in fact he too could have done a feature about beer in Bonn, ‘but it would not have been printed’.Footnote77 In television, the situation was different. The costs associated with the production of a story made it unwise to film something with questionable broadcasting potential.

It is a curious fact that the expansion of the GDR correspondent network came precisely as the Western media cut their networks of foreign correspondents. Rising prices and changing readership preferences resulted in a drop of full-time American correspondents from 797 in 1972 to 429 just three years later.Footnote78 In West Germany a small scandal erupted in 1975 when news broke of the costly foreign correspondent network maintained by the public broadcaster ARD. Analyses deemed travelling correspondents to be about 25% cheaper than permanent foreign correspondents, and ARD soon reduced their number of journalists posted long-term at foreign bureaus.Footnote79 Mirroring developments in Western foreign news reporting, the head of DDR-FS, Heinz Adameck, announced in 1979 that in the future the broadcaster would rely increasingly on ADN and Neues Deutschland correspondents. Travelling correspondents were by no means substandard reporters, Adameck was keen to stress.Footnote80 However, that very reassurance belies Adameck’s awareness of the changing circumstances in the production of foreign news, presaging subsequent decades’ parachuting of poorly prepared journalists whenever a crisis erupts in a faraway place.Footnote81

Conclusion

The aim of this article has been to open a new line of research on Eastern bloc foreign correspondents in the West. While previous scholarship primarily focused on media content and Western journalists reporting from the Eastern bloc, we argue that to trace Eastern bloc reporting from the West provides us with new knowledge about the entangled media histories, cultures, and politics of Cold War Europe. It contributes to the growing historical research on foreign correspondents and media in East Germany and beyond.

In this article, we have also indicated that a transnational media perspective can be fruitfully combined with influences from other expanding fields such as for example New Diplomatic History, which emphasizes not only the diplomatic actions of non-diplomatic agents, but also the often complex cultural contexts in which the agents were embedded. The case of the Nordeuropa bureau of Aktuelle Kamera has been highlighted to illustrate how East Germany’s foreign correspondents in the 1970s served as political agents and intelligence officers on semi-official missions while their professional work required a constant navigation of cultural, economic, logistical, and technological obstacles. The trials and tribulations of DDR-FS correspondent Heinz Sachsenweger offer an insight into the transnational production context of foreign news reporting, as he navigated national and ideological boundaries between his home office in East Berlin and the capitalist West. As a GDR foreign correspondent on television, travelling between East and West, he was both a cultural and political ‘cold warrior’, although his primary everyday frustrations were of a far more practical and mundane kind. The article thus points to the importance of materiality in journalistic practice. By looking at Sachsenweger and his work, our attention is directed not only to the media content and ideological propaganda in East German television, but also to the correspondent’s way of navigating the practical challenges of the media systems on either side of the Cold War divide.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Dr Jörg-Uwe Fischer for his invaluable help at the Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv, Rosamund Johnston, Laura Saarenmaa, and the editors of this special issue for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Sune Bechmann Pedersen http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4762-7962

Marie Cronqvist http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2340-3729

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sune Bechmann Pedersen

Sune Bechmann Pedersen, Department of Communication and Media, Lund University, Box 117, 221 00 Lund, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]

Marie Cronqvist

Marie Cronqvist, Department of Communication and Media, Lund University, Box 117, 221 00 Lund, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1. Domeier and Happel, ‘Journalismus und Politik,’ 389.

2. Birkner, ‘Correspondents and the Cold War’; Hamilton and Jenner, ‘Redefining Foreign Correspondence,’ 310.

3. Carruthers, The Media at War, 8–11.

4. Fainberg, ‘Unmasking the Wolf.’

5. Alwood, ‘The Spy Case.’

6. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg, 59–64; Thiemeyer, ‘Wandel durch Annäherung,’ 107.

7. Gram-Skjoldager, ‘Bringing the Diplomat Back’; Scott-Smith, ‘Private Diplomacy.’

8. Cohen, The Press and Foreign Policy, 17.

9. Cronqvist and Hilgert, ‘Entangled Media Histories,’ 132.

10. Hahn et al., ‘Deutsche Auslandskorrespondenten.’

11. Domeier and Happel, ‘Journalismus und Politik’; Bösch and Geppert, Journalists as Political Actors; Hannerz, Foreign News; Jarlbrink, ‘News Work.’

12. In 1972, East German television changed its name from Deutscher Fernsehfunk (DFF) to Fernsehen der DDR (DDR-FS).

13. Metger, Studio Moskau; Fainberg, ‘Cold War Expert.’

14. Magnúsdóttir, ‘Cold War Correspondents.’

15. Fengler, ‘Westdeutsche Korrespondenten’; Winters, ‘West-Korrespondenten.’

16. Thiemeyer, ‘Wandel durch Annäherung.’

17. Bösenberg, Aktuelle Kamera.

18. Minholz and Stirnberg, Allgemeine Deutsche Nachrichtendienst.

19. Gißibl, ‘Deutsch–deutsche Nachrichtenwelten.’

20. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg.

21. Kilian, Die Hallstein-Doktrin.

22. Thomas, ‘Normalisation,’ 37–41.

23. Minholz and Stirnberg, Allgemeine Deutsche Nachrichtendienst, 281–7.

24. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg, 27, 117–51.

25. Fiedler, Medienlenkung in der DDR, 116.

26. Thesis by Thomas Wolter quoted in Minholz and Stirnberg, Allgemeine Deutsche Nachrichtendienst, 287.

27. Fiedler, Medienlenkung in der DDR, 247–48.

28. Minholz and Stirnberg, Allgemeine Deutsche Nachrichtendienst, 287–8, 433–8.

29. Gumbert, Envisioning Socialism.

30. Steinmetz and Viehoff, Deutsches Fernsehen Ost, 116.

31. Das Deutsche Rundfunkarchiv (DRA), Aktuelle Kamera (AK), Korrespondentenabt. Chefred. S. Leske, vol. 1905 [Anordnung über Planung], ‘Rechenschaftsbericht,’ 10 December 1975.

32. DRA Presseklip, Medienmitarbeiter, Journalist, Auslandskorresp., b: 1985.

33. Fiedler, Medienlenkung in der DDR, 247.

34. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg, 21.

35. Meyen and Fiedler, Journalisten in der DDR, 347–48. The situation was much the same in West Germany when a new media system was constructed from the ruins of the Nazi propaganda machine. Gißibl, ‘Aufbau der Auslandsberichterstattung,’ 436.

36. Meyen and Fiedler, Journalisten in der DDR, 351.

37. Ibid., 354.

38. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg, 21.

39. Fiedler, Medienlenkung in der DDR, 104–19.

40. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg, 395.

41. Meyen and Fiedler, Journalisten in der DDR, 357.

42. Staab et al., ‘Die Darstellung des Auslands.’

43. Behling, Fernsehen aus Adlershof.

44. Kilian, Die Hallstein-Doktrin, 44–8; Berger and Laporte, Friendly Enemies, 72–3.

45. Muschik, Eine Dreiecksbeziehung, 149.

46. Linderoth, Kampen för erkännande, 78–81; 131–5.

47. Ibid. 101–09.

48. Riksarkivet (Swedish National Archives), Utrikesdepartementet (Ministry of Foreign Affairs) I7 Ct, vol. 3.

49. Cronqvist, ‘Between Scripts.’

50. See, for example, Sachsenweger’s Aktuelle Kamera reports 1 Jan 1976 (DRA FESAD prod. no. 304797), 10 April 1976 (ibid. 096070), and 15 June 1976 (ibid. 300626).

51. Weper, ‘Vor mand i Kopenhagen,’ Information, 24 June 2000.

52. Ibid.

53. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg, 188.

54. Ibid., 395–6; Herden, ‘Erfahrungen eines Auslandskorrespondenten,’ 327.

55. Fiedler, Medienlenkung in der DDR, 115.

56. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht Oktober,’ 31 October 1974.

57. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg, 95–96; Stasi sources generally reported with a heavy bias against the West which produced an ‘echo-chamber effect’. See for instance Gieseke, Die Stasi, 227.

58. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht September,’ 1 October 1974.

59. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht April - Mai,’ 3 June 1975.

60. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht März,’ 1 April 1975. It was released in Sweden as Gatlopp.

61. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht März,’ 1 April 1975.

62. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht September,’ 1 October 1974.

63. DRA, AK, Korrespondentenabt., vol. 1907, Büro Lissabon, Volker Ott to Leske, 5 February 1984, p. 2.

64. Ibid., p. 3.

65. DRA, AK, Korrespondentenabt., vol. 1907, Büro Lissabon, ‘Missbilligung,’ 10 October 1983.

66. DRA, AK, Korrespondentenabt., vol. 1906, Sicherheitsfragen.

67. See especically DRA, AK, Korrespondentenabt., vol. 1907, Büro Paris.

68. DRA, AK, Korrespondentenabt., vol. 1907, Büro Sofia, letter dated 24 July 1988.

69. DRA, AK, Korrespondentenabt., vol. 1907, Büro Sofia, letter dated 31 July 1988, p. 2.

70. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg, 393.

71. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht Januar,’ 5 January 1975.

72. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht Dezember,’ 2 January 1975.

73. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht Oktober,’ 31 October 1974.

74. DRA, SR—Schweden, vol. 48, Wichtige Berichte (Reiseberichte), ‘Monatsbericht Dezember,’ 2 January 1975.

75. Hannerz, Foreign News, 52.

76. DRA, AK, CSL, vol. 1905.

77. Mükke, Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg, 188.

78. Carmody, ‘World of the Foreign Correspondent.’

79. Evangelische Pressedienst, ‘Teure Stimmen von außen’; Nowoczyn, ‘Einige Sparangriffe wurden abgewehrt.’

80. bau, ‘Netz wird nicht erweitert.’

81. Hannerz, Foreign News, 52–3.

References

- Alwood, Edward. “The Spy Case of AP Correspondent William Oatis: A Muddled Victim/Hero Myth of the Cold War.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 87, no. 2 (2010): 263–280. doi: 10.1177/107769901008700203

- Bau. “Netz wird nicht erweitert.” Frankfurter Rundschau, 15 May 1979.

- Behling, Klaus. Fernsehen aus Adlershof: Das Fernsehen der DDR vom Start bis zum Sendeschluss. Berlin: Edition Berolina, 2016.

- Berger, Stefan, and Norman Laporte. Friendly Enemies: Britain and the GDR, 1949–1990. New York: Berghahn Books, 2010.

- Birkner, Thomas. “Correspondents and the Cold War: How Foreign Correspondents Acted During the Chancellery of Helmut Schmidt (1974–1982) in Germany and Abroad.” Sur le journalisme, About journalism, Sobre Jornalismo 5, no. 1 (2016): 16–29.

- Bösch, Frank, and Dominik Geppert, eds. Journalists as Political Actors: Transfers and Interactions Between Britain and Germany Since the Late Nineteenth Century. Augsburg: Wißner, 2008.

- Bösenberg, Jost-Arend. Die Aktuelle Kamera: Nachrichten aus einem versunkenen Land. Berlin: VVB Verlag für Berlin-Brandenburg, 2008.

- Carmody, Deidre. “World of the Foreign Correspondent Seems to Be Shrinking.” New York Times, 4 April 1977.

- Carruthers, Susan L. The Media at War. 2nd ed. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

- Cohen, Bernard Cecil. The Press and Foreign Policy. Princeton: PUP, 1963.

- Cronqvist, Marie, and Christoph Hilgert. “Entangled Media Histories: The Value of Transnational and Transmedial Approaches in Media Historiography.” Media History 23, no. 1 (2017): 130–141. doi:10.1080/13688804.2016.1270745.

- Cronqvist, Marie. “Between Scripts: Radio Berlin International (RBI) and its Swedish Audience in November 1989.” In Remapping Cold War Media: Institutions, Infrastructures, Networks, Exchanges, edited by Alice Lovejoy, and Mari Pajala. Bloomington: Indiana University Press (in press, expected November 2019).

- The Defector (Lautlose Waffen/L’espion), directed by Raoul Levy, 1966. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros., 2009.

- Domeier, Norman, and Jörn Happel. “Journalismus und Politik: Einleitende Überlegungen zur Tätigkeit von Auslandskorrespondenten 1900–1970.” Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 62, no. 5 (2014): 389–397.

- Evangelische Pressedienst (epd), “Teure Stimmen von außen.” Stuttgarter Zeitung, 19 April 1975.

- Fainberg, Dina. “A Portrait of a Journalist as a Cold War Expert.” Journalism History 41, no. 3 (2015): 153–164. doi: 10.1080/00947679.2015.12059126

- Fainberg, Dina. “Unmasking the Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing: Soviet and American Campaigns Against the Enemy’s Journalists, 1946–1953.” Cold War History 15, no. 2 (2015): 155–178. doi:10.1080/14682745.2014.978762.

- Fengler, Denis. “Westdeutsche Korrespondenten in der DDR: Vom Abschluss des Grundlagenvertrages 1972 bis zur Wiedervereinigung 1990.” In Journalisten und Journalismus in der DDR: Berufsorganisation—Westkorrespondenten—‘Der schwarze Kanal’, edited by Jürgen Wilke, 79–216. Cologne: Böhlau, 2007.

- Fiedler, Anke. Medienlenkung in der DDR. Cologne: Böhlau, 2014.

- Gieseke, Jens. Die Stasi: 1945–1990. 3rd ed. Munich: Pantheon, 2011.

- Gißibl, Bernhard. “Die Vielfalt des Neuanfangs: Zum Aufbau der Auslandsberichterstattung des öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunks nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg.” Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 62, no. 5 (2014): 425–436.

- Gißibl, Bernhard. “Deutsch–Deutsche Nachrichtenwelten: Die Mediendiplomatie von ADN und dpa im frühen Kalten Krieg.” In Kulturelle Souveränität: Politische Deutungs- und Handlungsmacht jenseits des Staates im 20. Jahrhundert, edited by Gregor Feindt, Bernhard Gißibl, and Johannes Paulmann, 227–256. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2017.

- Gram-Skjoldager, Karen. “Bringing the Diplomat Back In: Elements of a New Historical Research Agenda.” EUI Working Papers RSCAS 2011/13 (2011).

- Gumbert, Heather L. Envisioning Socialism: Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2014.

- Hahn, Oliver, Julia Lönnendonker, and Nicole Scherschun. “Forschungsstand: Deutsche Auslandskorrespondenten und -korrespondenz.” In Deutsche Auslandskorrespondenten: Ein Handbuch, edited by Oliver Hahn, Julia Lönnendonker, and Roland Schröder, 19–43. Konstanz: UVK, 2008.

- Hamilton, John Maxwell, and Eric Jenner. “Redefining Foreign Correspondence.” Journalism: Theory, Practice & Criticism 5, no. 3 (2004): 301–321. doi: 10.1177/1464884904044938

- Hannerz, Ulf. Foreign News: Exploring the World of Foreign Correspondents. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Herden, Lutz. “Erfahrungen eines Auslandskorrespondenten der ‘Aktuellen Kamera’ vor und nach der revolutionären Wende.” In DDR-Fernsehen intern: von der Honecker-Ära bis ‘Deutschland einig Fernsehland’, edited by Peter Ludes, 322–330. Berlin: Volker Spiess, 1990.

- Jarlbrink, Johan. “Mobile/Sedentary: News Work Behind and Beyond the Desk.” Media History 21, no. 3 (2015): 280–293. doi:10.1080/13688804.2015.1007858.

- Kilian, Werner. Die Hallstein-Doktrin: Der diplomatische Krieg zwischen der BRD und der DDR 1955–1973: Aus den Akten der beiden deutschen Aussenministerien. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 2001.

- Linderoth, Andreas. “Kampen för erkännande: DDR:s utrikespolitik gentemot Sverige 1949–1972.” PhD diss., Lund University, 2002.

- Magnúsdóttir, Rósa. “Cold War Correspondents and the Possibilities of Convergence: American Journalists in the Soviet Union, 1968–1979.” Soviet & Post-Soviet Review 41, no. 1 (2014): 33–56. doi: 10.1163/18763324-04101003

- Metger, Julia. Studio Moskau: Westdeutsche Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, 2016.

- Meyen, Michael, and Anke Fiedler. Die Grenze im Kopf: Journalisten in der DDR. Berlin: Panama, 2011.

- Minholz, Michael, and Uwe Stirnberg. Der Allgemeine Deutsche Nachrichtendienst (ADN): Gute Nachrichten für die SED. Munich: Saur, 1995.

- Mükke, Lutz. Korrespondenten im Kalten Krieg: Zwischen Propaganda und Selbstbehauptung. Cologne: Herbert von Halem, 2014.

- Muschik, Alexander. Die beiden deutschen Staaten und das neutrale Schweden: Eine Dreiecksbeziehung im Schatten der offenen Deutschlandfrage 1949–1972. Münster: Lit, 2005.

- Nowoczyn, Robert. “Einige Sparangriffe wurden abgewehrt.” Frankfurter Rundschau, 3 March 1976.

- Scott-Smith, Giles. “Introduction: Private Diplomacy, Making the Citizen Visible.” New Global Studies 8, no. 1 (2014): 1–7. doi: 10.1515/ngs-2014-0012

- Staab, Joachim Friedrich, Georg Schütte, and Peter Ludes. “Die Darstellung des Auslands im Spannungsfeld zwischen journalistischer Autonomie und staatlicher Anleitung: Schlüsselbilder in Tageschau und Aktueller Kamera von 1960 bis 1990.” In Deutschland im Dialog der Kulturen: Medien, Images, Verständigung, edited by Siegfried Quandt, Wolfgang Gast, and Horst Dieter Schichtel, 53–62. Konstanz: UVK Medien, 1998.

- Steinmetz, Rüdiger, and Reinhold Viehoff. In Deutsches Fernsehen Ost: Eine Programmgeschichte des DDR-Fernsehens. Berlin: VBB, 2008.

- Thiemeyer, Guido. “‘Wandel Durch Annäherung’: Westdeutsche Journalisten in Osteuropa 1956–1977.” Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 45 (2005): 101–116.

- Thomas, Merrilyn. “‘Aggression in Felt Slippers’: Normalisation and the Ideological Struggle in the Context of Détente and Ostpolitik.” In Power and Society in the GDR, 1961–1979: The ‘Normalisation of Rule’?, edited by Mary Fulbrook, 33–51. New York: Berghahn, 2009.

- Winters, Peter Jochen. “West-Korrespondenten im Visier des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit der DDR.” In Macht und Zeitkritik: Festschrift für Hans-Peter Schwarz zum 65. Geburtstag, edited by Peter Weilemann, Hanns Jürgen Küsters, and Günter Buchstab, 281–292. Paderborn: Schöningh, 1999.