Abstract

This article examines how The Vegetarian Review, the monthly periodical founded in Kishinev and published in Kiev from 1910–1915, and the emerging vegetarian activism, enabled, re-affirmed and empowered each other. The focus of the article is on the periodical’s emergence, logistical aspects of its production, ideological settings, form, content, rationale, (re)presentational strategies, as well as the imaginaries constructed and articulated on its pages. By bridging the fields of periodical studies with the history of social activism in Eastern Europe, the role of the advocacy journal in promoting reform agenda and its potential for forging a community of values and a shared identity formation are discovered. Vegetarianism, as the study showcases, had been defined, debated, advocated, invented and negotiated on the pages of The Vegetarian Review through interaction between scribes, editors, readers, practitioners and activists; and its genre fostered, staged and empowered these exposures.

The Vegetarian Review aims to spread humanitarian ideas in society and provide advice and explanations to everyone who wants to join the vegetarian movement.Footnote1

Introduction

The societal and political changes endorsed from above and pushed from below throughout the last decades of the nineteenth century, associated with Russia’s ‘Great Reforms’ of the 1860s and 1870s and modernization, provided the printing press with the opportunity to develop and circulate on a large scale. The press, together with the postal service and other means of communication, came to influence the public sphere. The period also witnessed ‘new journalism’: some publishers and editors sought to offer readers engagement and interaction. The October Manifesto of 1905 with its freedom of assembly and the promise of a representative parliament gave impetus to the emergence of a variety of political parties, unions, associations, and occupational groups. Further reducing the autocracy’s control over public life, the ‘freedom of speech’ provision of the October Manifesto and the subsequent relaxation of the censorship regulations by the new press laws of November 1905 heralded the legal liberation of the Russian press. Although the ‘days of liberty,’ in the words of Oleg Minin, proved to be rather short-lived, they saw the emergence of periodicals of every editorial inclination and in the many languages of the empire.Footnote2 A lively multicultural public life had been evolving in the largest cities of the empire, as new professional, entrepreneurial, artistic, and scientific elites aspired to create new public identities.Footnote3

At the same time, the end of the nineteenth century until the First World War—was ‘the first era of globalization,’Footnote4 when border crossings became a mass-scale phenomenon and the flow of commodities, foodstuffs, knowledge and information over borders became common. Vegetarianism was one of many transcultural and trans-imperial phenomena of the era. As in Britain, America, Sweden and German-speaking countries in Europe, vegetarian activism in the Russian Empire, stimulated by societal change and urbanization, was also a feature of broader reformist environments. Depending on their ideological orientation, they addressed a wide range of issues concerning hygiene and consumption habits, dietary reform and temperance, compassion for animals and anti-vivisection, and called for a return to ‘natural ways of living,’ as well as endorsing abstinence and moral self-perfection.Footnote5 Organized vegetarianism in the Russian Empire emerged at the turn of the century, several decades after the British, American or Central European vegetarian movements. In the first decade of the 1900s, a network of vegetarian circles appeared. By the 1910s, vegetarian enthusiasts had mobilized themselves into vegetarian societies and developed an infrastructure in the imperial cities of Saint Petersburg, Kiev, Moscow, Minsk, Odessa, Poltava, Ekaterinoslav and etc. They also re-launched an advocacy journal.

The core questions underpinning this article are at the intersection of these fascinating developments. I aim to analyse The Vegetarian Review, a medium of vegetarian activism in the Russian Empire, by examining its emergence, genre, form, content, rationale and (re)presentational strategies. What imaginaries were constructed and articulated on the pages of The Vegetarian Review? What message did it convey to a public, how and why? What role (if any) could it play in promoting reformist agenda? To what extent could periodicals as a publishing genre, and the fledgling vegetarian activism have enabled, empowered and affirmed each another? Furthermore, I am interested in tracking the potential for and possibilities of shared identity formation around print media. I read The Vegetarian Review as a vehicle, a medium and a dynamic agent in its own right, bridging the fields of periodical studies with collective identit(y)ies formation in Eastern Europe. However, measuring the real impact of the journal on the fledgling vegetarian activism and life-reform movement(s) is hardly feasible with available sources and beyond the scope of this enquiry.

As Margaret Beetham highlights, each article and every issue of a periodical constituted a process in which writers, editors, publishers and readers engaged in meaning-making.Footnote6 Beetham has laid the theoretical foundation for this study. Her theory of the periodical as an open and closed genre allows the interpretation of the activity of producing and reading periodicals as one of the twentieth century’s most significant tools for forging new associations. Theorizing on the Janus-like characteristics of the periodical, Beetham defines it as a self-referring (with constant references to past and future issues) and both an open-ended and end-stopped genre: open because it allows readers to choose which articles to read and in which order; closed because it appears within a regular temporal framework, and its form has ‘a deep regular structure.’ The periodical’s heterogeneity (comprising of different kinds of material), the possibility of selective reading and the blurred boundaries of the genre provided readers with diverse entry points through which to approach the text, allowing them to construct their own experience of the text by selecting what they read and engaging in the development of the content.Footnote7

One of the ‘counter-cultural’ resources of the British vegetarian movement, as James Gregory claims, were its press. The vegetarian press in Britain intended to attract new members, to create a national and international movement, to inspire its adherents through a sense of community and through the information it published. Similar to the provision of foodstuffs, the literary needs of the movement were also provided by entrepreneurs hoping to make a living out of the ‘trade of agitation’ and reform.Footnote8 Liam Young’s dissertation places the discussion on the interconnectedness of print media and vegetarian society in England.Footnote9 This is the point of reference and departure for my own study. Peter Brang, author of a pioneering study on vegetarianism in Russia, initiated a cursory discussion on vegetarian journals per se in the Russian imperial context. However, due to the focus of his inquiry, he did not go into the issue in depth.Footnote10 There is a lack of interdisciplinary studies on imperial Russian pressure-group periodicals as a medium of life-reform and social activism, as well as a space for forging new associations and collective identities. Hopefully, my examination of a dimension that has not yet received much attention in the history of the Russian Empire and Eastern Europe—the entangled space of the formation of the community of values and the role of the periodical in it—will stimulate further debate.

Not a Pioneer but a Successor

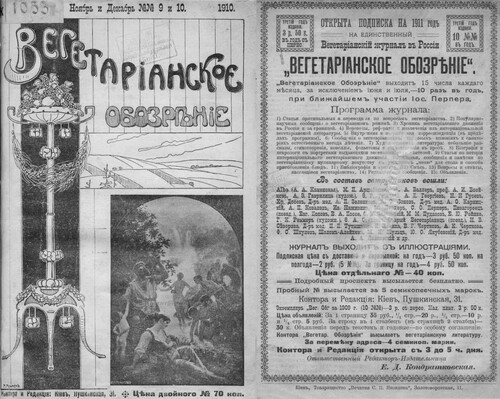

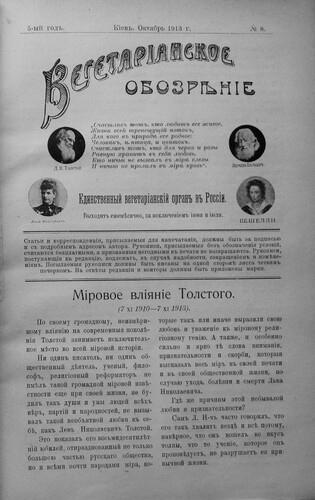

The first vegetarian journal of the Russian Empire, The Vegetarian Herald (Vegetarianskii vestnik), was published in St. Petersburg from January 1904—June 1905 under the editorship of Bronislav Doliachko. The reason for the short existence of the periodical remains unclear. According to Iosif Perper, in 1905 the journal needed funds and, due to circumstances that caused Doliachko to leave St. Petersburg, he had to close the journal, which had been causing him major losses. Footnote11 On 31 December 1908, official permission was obtained for publication of The Vegetarian Review (Vegetarianskoe obozrenie, later, VR) subtitled as the only vegetarian journal in Russia and founded by brothers Iosif and Moisei Perper. Its first issue was published in Kishinev (Chișinău) on 19 January 1909.Footnote12 From 1910, the journal was published in Kiev. At the end of 1914, the prospect of moving the journal to Moscow was discussed but not realized.Footnote13

In 1914, Iosif Perper described the closure of The Vegetarian Herald in 1905 as a great loss for the ‘vegetarian movement.’ By this point, he continued, there had been two vegetarian societies, lectures on vegetarianism were very infrequent and there had been only ten vegetarian canteens across the empire. Up to then, vegetarian circles lacked ‘an intermedium’ (sviazuiushchee zveno) and ‘vital communication’ (zhivoe obshchenie).Footnote14 He continued:

All this to me, living in the province, had to feel a lot. As I wanted to promote the idea of vegetarianism to unite like-minded people, I decided to publish a Russian vegetarian journal. The need for such a journal was strongly felt. […] With the advent of the journal, it becomes easier to trace the further history of the vegetarian movement in Russia in recent years.Footnote15

The journal was published monthly, ten issues a year, except for June and July. The size of the journal was never fixed and varied from 32 to 46 pages. The price of an annual subscription with delivery within the Russian Empire remained unchanged during the entire existence of the journal and cost 3.5 roubles: a six-month subscription cost 2 roubles; a post-pay alternative cost 4 roubles; delivery abroad cost 4.5 roubles. The retail price of the periodical ranged from 25 to 40 kopecks, for the duplex issue—70 kopecks.

The production of The VR was in the hands of the editorial team, comprising around 30 people, who were also the authors of articles or column leaders. During the journal’s existence, the main responsibility for it circulated among its chief editors—Moisei and Iosif Perper, Ekaterina Kondratkovskaia, Evgenii Sklovskii, along with publishers—Iosif Perper, Ekaterina Kondratkovskaia and Lev Fish. Moving away from his direct duties for the journal time and again, Iosif Perper always kept an eye on developments. An illustration of this is an inscription on the cover of the journal affirming that the journal was published ‘with the closest participation of Iosif Perper.’ The editorial staff comprised intellectuals; some of them operated in different parts of Europe (for example, Italy and Finland), as well as North America. The distances, however, were diminished by postage and did not appear to affect the editorial coherence. Footnote16 Not much is known so far about editors and publishers of the journal, nor is it easy to find information about them in the sources. A Bessarabia born Iosif Perper (1886–1965) was a devoted vegetarian, a journalist, and a person whose input into the propelling of the vegetarian activism is hard to overestimate. Being a Tolstoy admirer, he at the same time was an active member of Germanic Vegetarian Union, participating in its important events and publishing in its journal, The Vegetarian Watch (Vegetarische Warte). A supporter of Jewish community to which he himself belonged, Perper came close to establishing the first vegetarian journal in Yiddish and the first Jewish vegetarian publishing house in Kiev in the world in 1911.Footnote17 Notably, The VR invited to cooperation Sholem Aleichem, a prominent Yiddish cultural figure: he joined the editorial team of the journal in 1910. It is also telling that the pages of The VR also hosted for Jewish periodicals. Evgenii Sklovskii (1869–1930), Doctor of Medicine, professor of the Kiev Imperial University of Saint Vladimir, paediatrician, medical scientist, healthcare organizer, authored scientific works on organization of maternity and childhood protection, infant care, and prevention and treatment of childhood diseases .

According to Gregory, vegetarian journals in Britain were partly a typical propagandist tool ‘to win converts to a cause’. Footnote18 Nowadays, the word ‘propaganda’ suggests the biased use of information. However, in previous centuries, the term appears to have had neutral connotations synonymous with promotion. Young shows that vegetarians in Britain were not shy in describing their publications as ‘organized propaganda’ and indicates that no matter how progressive the principles they advocated were, all forms of propaganda aim to reproduce ideas, principles or practices in others.Footnote19 If we stick to this understanding, we can read The VR as both a form of propaganda and as something more than a pressure-group periodical.Footnote20 Propagating vegetarianism meant managing information to influence attitudes, as well as enlighten people on how to eat and live.

The VR was transparent about its function and called itself an ideinyi zhurnal, one that aimed at spreading vegetarianism by means of printed word and providing advice and explanations to potential activists. In an introductory parting word for the seventh year of The VR in 1915, Ivan Gorbunov-Posadov boldly declared the constant need for ‘the propaganda of natural life conducted by the journal,’ so the spiritual and physical forces of a person would develop in all their fullness and harmony. Footnote21 The editorial team and vegetarian societies saw the journal as an important tool for educating the masses. Reaching out and visibility were important milestones of this work. For the ‘purposes of propaganda’ of vegetarianism, on 4 October 1911 the Board of the Kiev Vegetarian Society decided to send 300 issues of The VR to all members of the society and the major city libraries of imperial Russia.Footnote22 From December 1913—March 1914, The VR received funds from the Poltava, Saratov and Petrograd Vegetarian Societies and someone called Engel’meier, enabling the distribution of 34 annual copies of The VR to the reading rooms of 34 public libraries in Petrograd, to Riazan and Kiev provinces, as well as 10 annual copies of The VR to the Saratov province in 1915.Footnote23 In March 1913, the Kiev Vegetarian Society, spurred by Iosif Perper, decided to buy a subscription of 200 annual copies of The VR for 200 libraries. Society members reckoned that ‘if at least 50 people in each library read the journal, then 10,000 of them would become acquainted with vegetarianism.’Footnote24 The journal was available for sale at vegetarian canteens run by vegetarian societies, Footnote25 as well as distributed by activists. In contrast to the British example, The VR was not a mouthpiece for any vegetarian society, although its editors and authors were members of various vegetarian societies. The VR branded itself as the ‘only vegetarian organ in Russia,’ the organ of ‘all Russian [rossiiskikh] vegetarians’ and the brainchild (detishche) of vegetarians in Russia.

The small scale of vegetarianism and the movement’s fragmentation meant that few vegetarian journals across Europe made a profit. The VR experienced constant financial difficulties. It was mainly supported by donations from The VR’s employees and publishers, vegetarian societies and individuals,Footnote26 as well as fees from lectures by Iosif Perper.Footnote27 In November 1913, the Odessa Vegetarian Society donated 100 roubles to The VR.Footnote28 In the same year, donations were also received from, for example, V.P. Rogacheva (Moskva)—20 roubles, 5 kopecks, V. Suliamova (Ekaterinoslav)—10 roubles, an unknown group (Iur’ev)—9 roubles, 62 kopecks. Footnote29

Constant economic concerns occasionally affected the goodwill of the editor in making the journal affordable to the population. In the ninth issue of 1913, the editor reported on the cessation of preferential subscriptions for 1914 since the journal was suffering losses. Footnote30 In an attempt to make the journal more affordable, a preferential subscription was introduced from 1915 for workers, peasants and teachers, which cost 2.5 roubles instead of 3.5 roubles.Footnote31 The financial situation of the journal suffered at the outbreak of the First World War. On 14 December 1914, the editorial office appealed to ‘like-minded people, subscribers and readers,’ explaining the dilemma of whether or not to open a subscription for 1915 or terminate the publication, thereby involving them in the problems of the journal’s future. It was stressed that The VR as an ideinyi zhurnal had experienced a deficit since it had first been launched. ‘Considering that the solution to the problem of the continued existence of The VR belongs not only to us [office], but to all like-minded people and readers,’ readers were asked to answer a questionnaire comprising 12 questions and return the answers, to be published in issue no. 10. In order for The VR to continue to exist, the office emphasised that ‘we need more subscribers and resources and only the broad promotion of the organ on the part of subscribers can help us in this respect.’ If there was no empathy and assistance from subscribers and readers, the office continued, the journal would be closed. Among the questions addressed were the following: ‘Do you consider further publication of The VR to be necessary?’ ‘Are you going to subscribe to The VR for 1915?’ ‘Are you going to buy an extra copy for 1915 (one or several) of The VR for a library or some acquaintances?’ ‘Can you promote The VR?’ ‘What do you believe are the positive and negative sides of the journal?’ ‘What articles interest you most?’ ‘How many years have you subscribed to The VR?’ ‘What in your opinion should be added?’ Footnote32

The tenth issue of the journal opened with brief information on the results of the questionnaire. Around one half of subscribers answered the questionnaire and all answers but one were positive. According to the editor, many readers decided to buy extra copies of The VR for 1915 for promotional purposes. Eight positive answers from subscribers regarding two questions from the questionnaire were published. Among these was a response from Abram Romanovskii:

Yes. I think the journal is essential, particularly for provincial people, who, not seeing sympathizers around, need moral support, which the journal gives them.Footnote33

The form of the journal was heterogeneous, encompassing articles, serialized fiction, photographs, culinary sections, letters and comments. It contained illustrations and there was a segment for advertisements. Ads in The VR cost 3 roubles a year. A Riga-based health resort for chronic patients, the Pernov health resort in the Livland province on the Baltic seashoreFootnote36 and a vegetarian guesthouse in French NizzaFootnote37 advertised in the journal. The addresses of some vegetarian canteens in the empire could occasionally be found. Advertisements by individuals rarely appeared: a ‘young vegetarian female’ from the Mogilev province was seeking a job as a housemaid or a saleswoman at a vegetarian canteen; a man from Belarusian Smoliany was seeking a job as a gardener for vegetarians.Footnote38 Unlike the British vegetarian periodicals, advertisements for vegetarian foodstuffs and commodities were absent in The VR.Footnote39 However, the last pages of The VR were extensively filled with the adverts of other periodicals such as Free Education (Svobodnoe vospitanie), Our Health (Nashe zdorov’e (Unser Gesund in Yiddish), Garden and Kaleyard (Sad i ogorod), Home Doctor (Domashnii doktor), Herald of Theosophy (Vestnik teosofii), Esperanto Wave (Volna Esperanto), Spiritual Christian (Dukhovnyi khristianin), the children’s journal Lighthouse (Maiak) and Spikes (Kolos’ia, a Jewish children’s journal in Russian).

The VR ceased publication in 1915 after its May issue. In its last message to its readers, the editorial office stated that the Interim Press Committee had arrested and confiscated the fourth issue of The VR and three articles by its scribes could not be included in the current fifth issue, although no reason was given. Footnote40 In 1913, full censorship was established in the areas of military operations and partial censorship outside these areas. Another vegetarian periodical The Vegetarian Herald (Vegetarianskii vestnik), subtitled the organ of the Kiev Vegetarian Society, had been intermittently published in Kiev from May 1914–December 1917.

By launching the periodical, the Perper brothers engaged in producing one of the commodities of Russian imperial print culture—information. Its aim was the circulation of texts on dietary regimen in order to proselytize an alternative way of eating, thinking and being. The management and circulation of information on the cause became one of the key features of vegetarian activism.

The Manifesto

Vegetarian societies founded in many of the empire’s cities in the early twentieth century had three common goals: to promote a slaughter-free diet among the population, disseminate information about the benefits of dietary reform via publications, lectures, articles in print media, and facilitate closer communication between people interested in vegetarianism. Footnote41 The ideological dispute over the issue of why a person should abstain from meat eating became the main divisive factor, as Ronald LeBlanc emphasizes. Divisions appeared not only between those who advocated a meat-free diet on scientific grounds and those who avoided meat out of moral and humanitarian convictions, but also between the adherents of this latter group who were secular vegetarians and those who abstained from eating meat because of religious or ascetic reasons. LeBlanc also speaks of influential and high-profile activists—Lev Tolstoy’s zealous disciples—who pursued a purposeful campaign of fashioning a more appealing image of their master, as a compassionate ethical and humanitarian vegetarian rather than a religious and ascetic one.Footnote42 Also, discussions regarding not only what brand of vegetarianism to propagate, but how to do so, raged between competing groups.

So, let’s look more closely at the ideological settings of the journal. The first issue of the journal opened with an introductory statement ‘Our aims,’ in which the editorial office promised to ‘meet the broad masses of people’ and provide ‘full coverage’ of the question of vegetarianism. The opening article concluded with the following line: ‘Our goal is humanity. Our slogan—‘Viva Life!’’Footnote43 Aquatic metaphors would signify the renewal ethos of the ‘movement’ and its universality. Metaphorical comparisons of vegetarianism with a stream ‘in narrow and wide streams rushing around’ appeared in other texts by Iosif Perper. Footnote44 In the second article, ‘What is vegetarianism?’, Perper provided his version of an ‘idea of vegetarianism,’ linking it to humanity, nature and naturalness. In his words, ‘vegetarianism primarily rejects slaughtered food, since it is obtained through killing, which corrupts humanitarian feelings, destroys the beauty of the world around us, and ruins the lives of both animals and people.’ Perper called vegetarianism ‘only ‘the first step’ in the ladder of human ideals,’ establishing a discursive link to Lev Tolstoy’s philosophy. Finally, Perper concluded that ‘struggling for humanity, vegetarianism does not recognize nationality, class inequalities and other frameworks established by people.’ Footnote45 With these two concise and sharp texts, the editorial office and/or Iosif Perper presented the journal’s ideological standpoints and perspectives on vegetarianism.

On 30 January 1909, the editorial office published a note ‘To Like-minded People and Readers!’ with a call to

recruit followers for us, increase the number of readers of The Vegetarian Review, love this organ, for your blood and flesh are in it, because it is the brainchild (detishche) of all Russian (rossiiskikh) vegetarians. Footnote46

By publishing the note ‘Let’s hit the road’ in the last issue of 1909, the editorial office opened a subscription for the journal for 1910. Permeated by a militant vocabulary, its message is impregnated with the rhetoric of immortal and omnipotent love, a renewed self to be found in ‘the eternal brotherhood of all mankind’ and that the journal would strive to awaken it in the reader. It concluded with the following lines:

[…] We will strive to keep our great banner as firmly and higher as possible – love and compassion for all living things, recruiting more and more warriors, for the joint struggle and work for a bright, good present and near future. Like before, we will fight and defend by all means our slogan ‘Long live life’ (da zdravstvuet zhizn’) and strive for a great, single goal – humanity. […] Footnote47

Monthly Places, Entangled Spaces

The VR’s content encompassed the publication of series of Russian and international vegetarian literature and fiction linked to ethical and religious motifs of a meatless diet, polemical articles and feuilletons, discussions on different aspects of a meatless diet, on visits to slaughterhouses, on issues of raising children and pedagogy, as well as reviews of vegetarian literature. There were articles about vegetarian diets in Central Africa or Japan or the potential of the Turkestan region and the Caucasus regarding vegetarian settlements. The editors and publishers worked on diversifying the journal’s content and expanding its sections within the continuities of format and pattern of contents. In conjunction with the opening of a subscription, Iosif Perper pursued a ‘Conversation with readers’ (Beseda s chitateliami). He announced new rubrics and innovations to come, old topics to be continued, preferential subscriptions, described the journal’s financial losses, and elaborated on the general guidelines of the editorial office’s work regarding the future content. These ‘conversations’ were permeated by an appeal to the readers to distribute The VR and to recruit subscribers, due to the common cause.Footnote48 Bridging the past and the future with the present, these ‘conversations’ conveyed a sense of editorial presence and reader involvement. The various manifestations of the journal, elaborated on the following pages, offer a rich field for examining how editors, publishers, activists and readers from across the empire were encouraged to use print and the rhythms of the periodical to create a community based on common reading, meatless eating and reformed consumption.

Forging the Community

The print media played a crucial role in the development of urban environments, in the evolution of communication networks and in the dissemination of information and ideas. This chimes with Benedict Anderson’sFootnote49 well-known claim that the ‘imagined communities’ of the modern world were catalysed by particular qualities of the print media, engendering fundamentally new forms and standards of culture and association. The illustrations from Poltava and Vologda clearly prove that the printed word is a crucial means of mobilizing vegetarians in local settings. In December 1911, the local newspaper Poltava Voice (Poltavskii golos) published a letter ‘to like-minded people’ sent by Esfir Kaplan. She proposed that Poltava people, sympathising with the idea of vegetarianism, should ‘get acquainted’ with the purpose of opening a vegetarian canteen, society etc., thereby bringing closer the practical realization of the ideal of vegetarianism. Kaplan also asked for feedback. Footnote50 Vegetarian enthusiasts in Poltava were connected. In Vologda, Iu. Svetlov asked the local newspaper to publish his appeal to all vegetarians of Vologda to send him a request to partake in activities of the planned vegetarian society. Ten people responded and formed a community, which discussed the charter of the future society and established a vegetarian library. Footnote51

Sympathizers of vegetarianism, members of vegetarian societies and employees of The VR themselves were disseminated across the large part of the empire. They didn’t always live close to other vegetarians or have the opportunity to attend lectures, meetings or eat in vegetarian canteens. Thus, The VR represented a forum for converted vegetarians. In one of the journal’s sections presented as a chronicle of the vegetarian movement in Russia, it was possible to read about new initiatives, lectures, societies that had been established, new canteens and published literature. The statistics on membership of vegetarian societies and on annual visitors to vegetarian canteens would evidence and capitalize the progress of the collective action, reassuring activists in remote corners of the empire to continue the cause. The publication of fragments of the reports of vegetarian societies concretized the vegetarian collective body in print, visualizing this community. The joint insider identity was to be strengthened by the account of the preparation and conduct of the First All-Russian Vegetarian Congress and exhibition in Moscow in 1913. Publication of the correspondence between Tolstoy and Perper, Natal'ia Nordman-Severova and Perper, articles about various vegetarian figures, their ways to a fleshless diet and activities, brought legitimization to the activism, re-affirmation of the cause in the eyes of converts and kept the initiated loyal and bound to it. Discrepancies were inevitable, as well as disputes on doctrinal issues and ideological rifts. In ‘Conversations About Vegetarianism’ (Besedy o vegetarianstve), critical discussions on the ideological grounds of vegetarianism were serially and ardently pursued.

Nevertheless, the editors had to keep a balance between communicating to vegetarians and to the readership. As Brian Harrison notes, and Liam Young reminds us, pressure-group periodicals were often caught between the necessity to enlighten the uninitiated, with the aim of making new converts to the cause, and the necessity to inspire existing readers and activists. Footnote52 Content that interested insiders—reports, finances, lectures—was incomprehensible to newcomers. On the other hand, if a periodical attempted to broaden its audience by diversifying its content, it risked alienating its base readership. The VR manoeuvred between its needs: to communicate to vegetarians and sustain a loyal community in their work for the vegetarian movement, and to address the readership and encourage it to convert to new ideals.

The press was a significant mechanism for cultivating the imagined connections of reformist communities. Thus, the vegetarians’ dissemination of their unconventional worldview, lifestyle and dietary regimen across the borders rested heavily on the media, but also inexpensive postage and other means of communication. The VR’s objective was therefore more ambitious than just cultivating a community of vegetarians in the empire. Various sections led by The VR’s correspondents portrayed the developments of issue-orientated reform movements in Europe and America, allowing imperial Russian vegetarians to imagine themselves as being part of an international progressive community. The VR also offered compilations on the histories of vegetarian movements in, for example, England, Holland, Hungary, Scandinavia and Spain. In 1912, a series of articles by brothers Iosif and Samuil PerperFootnote53 were published under the rubrics of ‘Around Germany (Vegetarian Trips)’ and ‘Travel Impressions from Southern Switzerland,’ acquainting readers with vegetarian shelters, colonies, sanatoriums and like-minded foreign people. The VR aimed for detailed coverage of ‘major events in the international vegetarian world,’ such as congresses, conventions, exhibitions, etc., and it declared its readiness to send special correspondents to the required locations. Footnote54 Starting with the last issue of 1911, the ‘Around the World’ (Po miru) section (a chronicle of the vegetarian movement in Russia and abroad) which, according to Iosif Perper, was particularly popular among the readers, was extended. For this column, Samuil Perper, The VR’s correspondent in Rome, permanently joined the Old Vegetarian (most probably a pseudonym for Aleksandr Zankovskii). The readers were asked to send clippings, articles and notes on newspapers, books and other literature dealing with vegetarianism to the Old Vegetarian and to share any information of ‘general interest to the vegetarian movement.’Footnote55 Among other things, this section encompassed announcements of and reports on events and activities of relevance to the reform agenda of vegetarianism, as well as information on vegetarian societies and canteens in the Russian Empire and other parts of Europe. In 1912, a new section ‘The International Vegetarian Press’ was introduced, providing overviews of vegetarian periodicals from around the world.Footnote56

The VR compiled information on the activities and organizations connected to animal welfare, Esperanto, sport, theosophy, pedagogy, as well as printed reviews of vegetarian literature published in Europe and America, and overviews of articles in the local press of the Russian Empire on vegetarian issues. It was not merely a fleshless diet that was advocated, a plethora of texts on nutrition, health, hygiene, temperance, dietetics, hydropathy, anti-vivisection, physiology, housekeeping, child rearing, etc. was also served. The idea was to construct and brand vegetarianism as part of a broader reform agenda in society, as well as to fashion it as part of an international, if not a global, trend. A telling illustration of this self-fashioning are the portraits of five people on the front page of the journal—Anna Kingsford, Lev Tolstoy, Eduard Baltzer, Peshelli (probably Oscar Peschel), and Élisée Reclus (joined the gallery from 1914). Texts about and by these people, as well as other well-known vegetarians, such as Howard Williams, Footnote57 found their way into The VR. The third issue of The VR with an autobiographical note by Williams, compiled by L. Perno, was sent to Williams.Footnote58 Shortly afterwards, Perno received a letter from Williams expressing his gratitude and praise. Footnote59 For the ethos of the journal, it was important to construct, visualize and uphold international references .

Each month The VR aimed to present condensed statements about vegetarian principles, collecting information for readers from diverse sources. It also produced what Teresa Goddu described as a ‘centrifugal force’Footnote60—directing its readers outwards to other texts. The VR had been systematically advertising and selling Russian and translated literature on vegetarianism and its interrelation with ethics, hygiene, medicine, physical health, temperance, as well as vegetarian cookbooks. The ‘Russian Vegetarian Literature’ section, introduced in 1913, published reviews on Russian vegetarian volumes and the ‘In the World of Printing’ section presented articles and literature on vegetarianism.Footnote61

In a literal and figurative sense, The VR had not only promoted and sold other texts, volumes, journals through its advertisements and reviews, but also through references. The editorial office encouraged its readers and ‘like-minded people’ to send information linked to vegetarianism and which appeared in the press. Footnote62 Besides encouraging readers to monitor the information on the subject matter, dispersed and otherwise hardly accessible pieces of information obtained from readers were compiled and accommodated in the movement by means of centripetal force.

Rhythms of Interaction

Periodicals as participatory mediaFootnote63 enrol their audience, albeit asymmetrically, in their own production. The blurred boundaries of the periodical genre are evident in terms of its producers,Footnote64 when each issue forms part of a complex process in which different parties engaged in a wider process of ‘negotiation and struggle over meaning.’Footnote65 The balance between prescriptive and participatory features of the periodical genre, as Young maintains, is crucial for understanding the production and dissemination of vegetarianism in the pages of the British Vegetarian Advocate and Vegetarian Messenger. While these periodicals instructed readers on how to live their lives and what to consume and how, they also depended on contributions from readers, Young continues. All periodicals depended on contributions from readers, leastwise in the form of subscriptions; but vegetarian journals maintained an existential dependence on their audience.Footnote66 Statistics and annual reports of vegetarian societies, correspondence, conversion narratives and personal revelations—all of these made up the content of the journal while also displaying the vitality of a vegetarian idea and the zeal of its enthusiasts.

The VR virtually engaged with its readership in conversations (Iosif Perper’s ‘conversations’ with readers) and constantly appealed to them to distribute the journal. It also invited readers to intervene directly—by writing letters, comments and through other contributions. On the forefront of the journal, readers learned how to contribute to its content. The articles and correspondence for publication were to be signed and include the author’s detailed address. Manuscripts deemed unfit for publication were not returned. Manuscripts would be shortened and altered, if necessary. The translators were asked to send their translations with originals, indicating the full title of the article, as well as the name of the author in the language of the original.Footnote67 Overall, the journal was presented as a great collective enterprise.

In her correspondence to Iosif Perper, fragments of which were published in The VR,Footnote68 Natal’ia Nordman-Severova (1863–1914), a close friend of the Perper family, a suffragette and a zealous promoter of vegetarianism, expressed her indignation with respect to the editorial policy. On at least a few occasions she made it a condition that her texts and texts by her husband Ilya Repin, one of the most famous painters, must be published in the original version without changing a single word, otherwise she would leave the journal. Besides other issues addressed in letters, she suggested that a ‘sectarian body’ (sektantskii organ) should not be made out of a journal.Footnote69 In her opinion:

… It is absolutely necessary for you to arrange in the journal a unity between subscribers and the editors, as in The Messenger of Knowledge. Without this unity, the ideological journal is a stillborn child. An exchange of opinions with readers is a stream of warm, living blood!!! Let them ask, argue, consult, arrange excursions … Let you be the unifier of all trends of vegetarianism. I strongly feel that The Vegetarian Review needs a fresh, hot, new streak, otherwise it will be boring. And, of course, this new form of journal – uniting a live group of people under one banner – is the only way out.Footnote70

The VR depended on ensuring that readers continued to buy each issue as it was published. There was a tendency to keep reproducing and expanding elements which had been successful, such as the ‘Around the World’ section, and to link each issue with the next, orientating the readers’ interest towards the next issue of The VR. This was achieved by running series of articles, through references to past and future issues in different sections, through advertising, through readers’ letters and serialization.Footnote72 Writing ‘To be continued’ at the end of articles on ‘the history of the vegetarian movement in Russia,’ or on foodstuffs, was intended to keep readers intrigued and willing to return.

The ‘Letters to the Editor’ (Pis’ma v redaktsiiu) ‘Questions and Answers Concerning Vegetarianism’ (Voprosy i otvety, kasaiushchiesia vegetarianstva) and ‘Readers’ Voices’ (Golosa chitatelei) sections engaged with the audience in multiple ways across time and space, inviting them to intervene directly. The content of ‘Readers’ Voices’ is diverse. Nordman-Severova stated that she was no longer able to answer letters due to health issues. Vasilii Zuev, the chair of the Odessa Vegetarian Society, asked vegetarian societies to exchange their reports right after publication and Aleksandr Voeikov, the chairman of the St. Petersburg Vegetarian Society, made factual corrections to articles previously published in the journal. Iu. Raismik wondered about how to turn straw into manure without livestock, whereas P. Indiukok asked for the addresses of ‘like-minded people’ in Taganrog and Rostov for personal acquaintance.Footnote73

The editorial office not only provided the opportunity for interaction on The VR’s pages, but also correction of its content. Ia. Chaga highlighted ‘some inaccuracies’ to the editorial board in the ‘Around the World’ column in a previous issue of The VR regarding philosopher Nikolai Chernyshevskii, providing additional information about him. Footnote74 An anonymous reader reacted to the story of an attempt to start a journal, ‘The First Step’ (Pervaia stupen’) in 1893, described by Iosif Perper.Footnote75 According to the reader, the story presented in the article was not entirely accurate and the reader’s own version was published. Footnote76 The VR published a letter from peasant Pavel Salienko to the author of a novel that deeply touched the first one.Footnote77

Informing or asking to be informed, ‘A Letter to the Editor’ came from established vegetarians, scribes of the journal, as well as from ordinary readers. One could read about the foundation, institutionalization and initial activities of the Moscow Vegetarian Society.Footnote78 Semen Poltavskii, a member of the Saratov Vegetarian Society, intending to write a ‘people’s brochure’ on vegetarianism, asked his fellow colleagues—‘extramural correspondence friends’—to share by post their experiences of communication with the ‘common people’ on the issues of vegetarianism and give him input on possible perplexities, doubts and questions, likes and dislikes, that arose during these encounters.Footnote79 Vegetarians wrote letters to debate doctrinal issues and raise practical questions, as well as pursue critical discussions on The VR’s pages. ‘A Letter to the Editor’ sometimes became a platform for these. In 1911, a letter ‘Is it necessary?’ by K. Grekov was published. Despite the editorial board itself not agreeing with the author’s view on ‘raw food,’ as it acknowledged in the footnote, by its publication it intended to stimulate discussion on the topic. The piece addressed the so-called ‘extremes of vegetarianism’ (krainosti vegetarianstva), which went to extremes in its food from hay broth to vegetable garbage cutlets, in Grekov’s words. Footnote80 The publication of this letter initiated heated debates in the subsequent issues,Footnote81 and is further proof of the editor’s openness.

In the ‘Questions and Answers Concerning Vegetarianism’ section, questions were sometimes answered by the journal’s employees or were sometimes answered in subsequent issues. The questions might have been addressed together with reflections and personal opinions about the topic in focus. This was the case for Valentin Bulgakov, who asked the office and readers the following question: ‘How should vegetarians feel about the use of animal skin (in the form of footwear, belts, etc.) and, if they feel negatively about it, what could replace animal skin, especially as a material for shoe dressing?’ Another subscriber, D. Zaludik, wondered about literature that could ‘promote humane feelings in children.’ Articles and commentaries on suggested topics followed and the discussion developed. A. Georgiev, a VR employee, with reference to Bulgakov’s letter, wrote an article in which he reflected on vegetarianism and the use of animal skin, fur, antlers, fat, feathers, ivory and offered practical advice, tips and personal experience on how to replace animal-based constituents, as well as produce vegetarian footwear. Footnote82 Samuil Perper from Rome wrote an article referring to Bulgakov’s piece and Georgiev’s article. He acquainted readers with the situation regarding the production of synthetic leather in Western Europe.Footnote83

Doctor V. Piotrovskii asked for information on waxed canvas and linoleum for vegetarian shoes. A subscriber called Tsukanov asked for detailed addresses of trading companies that sold finished rubber soles.Footnote84 Responses to Piotrovskii and Tsukanov followed. Footnote85 A I. Iarkov from Samara asked if it was possible to replace so-called carpentry glue with glue with a plant origin, without compromising the bonding strength and price. A S. Iaralova from Kizlyar asked where she could buy clover hay, nettle and strawberry tea.Footnote86 A L. Shapirshtein responded to I. Iarkov’s question.Footnote87 A P. Zhukovskii asked if there was a shop in Kiev that sold vegetarian soap, or if, where and when a second All-Russian Vegetarian Congress would take place, among other things. Footnote88

The VR created serial links between readers, editors, scribes and activists around its content. It fostered a sense of audience engagement and agency and, by extension, generated a devoted community of readers, ‘like-minded people’ and ‘friends.’ This was achieved by providing a forum for discussion and debate, a meeting place for visualization and personification of the community, a space for negotiation, invention and transformation of consumption patterns, and a platform for constructing the meaning of vegetarianism and self-creation.

Personal Rhythms

The VR collected and circulated personal narratives in which vegetarians shared their experiences, motives and paths to a slaughter-free diet, as well as their narratives of the effects of the new regimen on their lives and health. These revelation narratives complemented facts and statistics, providing personified details to the abstract content of the journal and became an evidence of the viability and credibility of vegetarian ideas, and an important element in the promotion of vegetarianism. The accumulation of individual narratives and the distribution of personal stories about dilemmas on the path to a fleshless diet and reformed lifestyle, about encountered opposition and scepticism from society enabled disseminated readers to perceive themselves as a corporate body with shared experiences. The testimonies of vegetarians created the sections ‘How I became a vegetarian,’ ‘Why I became a vegetarian,’ ‘The voice of the peasant,’ ‘An event from my life’ (the title given to one letter) and ‘Three years (How I became a vegetarian)’ (the title given to one letter). Writings came from established vegetarians, scribes and The VR employees, as well as from the general public.Footnote89 It appears that there was a particular enthusiasm for peasant narratives. A long story by a peasant called Pavel Salienko, from a Ukrainian province, about his experience and route to vegetarianism, was published, according to the editor, in full and with no changes in style, though with some spelling corrections. Footnote90 The confession of a peasant called Liapin from the Saratov province was published with a note from the editor aiming to attract particular attention to it. This narrative was enthusiastically presented as the first sign of ‘a genuine, voluntary and conscious vegetarianism’ emerging in a Russian village.Footnote91

Individual narratives, disseminated through the post and gathered on the periodical’s pages, allowed fellowship and emotional bonds between strangers, providing the opportunity for collective association and identification.

Conclusion

The early twentieth-century vegetarian enthusiasts were a subgroup of eccentrics who rarely shared an immediate companionship. As The VR showcases, the periodical press could potentiate the carving out and uniting of a flock of disseminated people living on the margins of omnivorous culture. It was an imagined community, based not so much on direct interaction, but on the circulation of information. The VR not only distributed information on diet and life-reform to its readers, it also engaged them in its production and, by extension, in the construction of vegetarianism and a vegetarian self. The periodical genre of The VR complied with the needs and aspirations of what was branded as the vegetarian movement in the Russian Empire, allowing reciprocal inventions of one another. Vegetarians used periodical rhythms to cultivate new ways of thinking, living, eating, consuming and boosting the resolve of new recruits, as well as upholding the bounds of a loyal community. Besides bringing together a flock of vegetarians across the large part of the empire, The VR aimed to cultivate in its readers a sense of belonging to an international community.

However, its readers were not passive receivers. Through their personal narratives, comments, questions and input, the consumers of vegetarian advocacy became the creators of vegetarianism and its print medium. They were essential to the invention of the everyday vegetarian lifestyle and to the symbolical and rhetorical significance of the movement. The VR disseminated information on vegetarianism and tried to control its reception; but it depended on the information from and narratives of practitioners. The serial form of the periodical offered readers a shared public space to discover, monitor, document and exchange their literal and gastronomic practice of vegetarianism. The journal, not by chance, was continuously presented by its editors as a great collective enterprise. It constituted a cultural commodity endowed with substantial symbolic capital. Vegetarianism had been defined, debated, advocated, invented and negotiated on its pages through interaction between scribes, editors, readers, practitioners and activists; and its genre fostered, staged and empowered these exposures. At the same time, it is hard to assess how restrictive the editorial policy of the journal was in practice. While the instrumental goal of The VR was to advocate a fleshless dietary regimen and life reform, it created a space for vegetarians to fashion their own tastes, habits, bodies and patterns of behaviour and, by extension, new identity(ies) and a vegetarian self.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Julia Malitska

Julia Malitska, The Centre for Baltic and East European Studies, Södertörn University, Alfred Nobels allé 7 Flemingsberg, Huddinge 141 89, Sweden. E-mail [email protected]

Notes

1 From coverage of The VR for January 1913.

2 Minin, ‘The Value of the Liberated Word,’ 218.

3 Bradley, Voluntary Associations, 5–16.

4 Lohr, Russian Citizenship, 5.

5 From the extensive literature on the history of the vegetarianism in Europe and the USA, see: Brang, Rossiia neizvestnaia; Drouard, ‘Reforming Diet’; Gregory, Of Victorians and Vegetarians; Goldstein, ‘Is Hay Only for Horses’; Shprintzen, The Vegetarian Crusade; Thoms, ‘Vegetarianism, Meat and Life Reform’ and Malitska, ‘Meat and the City.’

6 Beetham, ‘Towards a Theory,’ 20–1.

7 Beetham, ‘Open and Closed,’ 96–100; Beetham, ‘Towards a Theory,’ 26–7.

8 Gregory, Of Victorians and Vegetarians, 141.

9 Young, ‘Eating Serials.’

10 Brang, Rossiia neizvestnaia, 284–99.

11 Iosif Perper, ‘K istorii vegetarianskogo dvizheniia v Rossii,’ Vegetariankoe obozrenie [later VO], no. 4 (1914): 125.

12 Staryi Vegetarianets ‘Po miru,’ VO, no. 9 (1913): 362.

13 Redaktsiia, ‘Sed’moi god,’ VO, no. 10 (1914): 307–8.

14 Iosif Perper, ‘K istorii vegetarianskogo dvizheniia v Rossii,’ VO, no.10 (1914): 314–5.

15 Ibid., 315.

16 ‘Redaktsionnoe soobshchenie,’ VO, no. 2 (1915): 80; ‘Redaktsionnye soobshcheniia,’ VO, no. 3 (1915): 114.

17 Staryi Vegetarianets, ‘Po miru,’ VO, no. 1 (1911): 48.

18 Gregory, Of Victorians, 149.

19 Young, ‘Eating Serials,’ 24.

20 Ibid., 24–25.

21 Ivan Gorbunov-Posadov, ‘S Bogom v put’!’ VO, no. 1 (1915): 1.

22 Staryi Vegetarianets, ‘Po miru,’ VO, no. 8 (1911): 35.

23 ‘Otchet kontory,’ VO, no. 10 (1914): 326.

24 Staryi Vegetarianets, ‘Po miru,’ VO, no. 3 (1913): 126.

25 According to Peter Brang’s estimate, by the outbreak of the First World War, there were 73 vegetarian canteens (both private and run by the vegetarian societies) in 37 cities: Chita, Helsinki, Ekaterinoslav, Elisavetgrad, Essentuki, Gelendzhik, Yalta, Kaluga, Khar’kov, Kishinev, Kislovodsk, Kokand, Lipetsk, Łódź, Moscow, Mineral’nye Vody, Minsk, Nikolaev, Odessa, Poltava, Riga, Rostov, Samara, Semipalatinsk, St. Petersburg, Tashkent, Tiflis, Tiumen’, Tobol’sk, Tomsk, Tula, Uman’, Vologda, Vilnius, Saratov and Warsaw. See Rossiia neizvestnaia, 28.

26 For further about the financial problems of the journal, see: Neliubina, ‘Vegetarianstvo,’ 208–15.

27 Staryi Vegetarianets, ‘Po miru,’ VO, no. 3 (1911): 37–8.

28 Otchet za 1913, 11.

29 ‘Otchet kontory,’ VO, no. 8 (1913): 326. Between 1893–1919, Iur’ev was the official name for Tartu, city in Estonia.

30 ‘Redaktsionnye soobshcheniia,’ VO, no. 9 (1913): 364.

31 ‘Redaktsionnye soobshcheniia,’ VO, no. 10 (1914): 326.

32 K edinomyshlennikam, podpischikam i chitateliam zhurnala ‘Vegetarianskoe obozrenie,’ ‘Oprosnyi listok "Vegetarianskogo obozreniia,"’ VO, no. 6–7 (1914): 255–6.

33 Redaktsiia, ‘Sed’moi god,’ VO, no. 10 (1914): 308.

34 Ibid., 307–8.

35 Staryi Vegetarianets, ‘Po miru,’ VO, no. 1 (1910): 36–9.

36 ‘Ob’iavleniia,’ VO, no. 4–5 (1913): 206.

37 VO, no. 10 (1913): 411; ‘Ob’iavleniia,’ VO, no. 4 (1914): 122.

38 VO, no. 4 (1915): 154.

39 VO, no.10 (1913): 411.

40 ‘Redaktsionnye soobshcheniia,’ VO, no. 5 (1915): 186.

41 The Saint Petersburg Vegetarian Society, the first one in the empire, was founded in 1901. In 1903 the vegetarian society was registered in Warsaw, in 1908 – in Kiev and Kishinev, in 1909 – in Moscow, in 1910 – in Saratov, in 1912 – in Odessa and Poltava, in 1913 – in Khar’kov and etc. The goals of the vegetarian societies were identically formulated in the charters of all societies of the empire. See Ustav S.-Peterburgskago Obshchestva, 3–4; Ustav Kievskago Obschestva, 3–4.

42 On ideological divisions within imperial Russian vegetarianism, see LeBlanc, ‘Vegetarianism in Russia,’ 11, 16–7, 25. On revisionist account of Tolstoy’s conversion to the meatless diet, see LeBlanc, ‘Tolstoy’s Way of No Flesh’.

43 Redaktsiia ‘Nashi tseli,’ VO, no. 1 (1909): 1–2.

44 Iosif Perper, ‘Besedy o vegetarianstve (Otvet Evgeniiu Lozinskomu),’ VO, no. 9–10 (1910): 51–4.

45 Iosif Perper, ‘Chto takoe vegetarianstvo,’ VO, no. 1 (1909): 3–4.

46 Redaktsiia ‘K edinomyshlennikam i chitateliam!,’ VO, no. 2 (1909): 18.

47 Redaktsiia, ‘V put’-dorogu (K otkrytiiu podpiski na 1910 god),’ VO, no. 10 (1909): 1–2.

48 Iosif Perper, ‘Beseda s chitateliami,’ VO, no. 9–10 (1911): 61–2; Iosif Perper, ‘Beseda s chitateliami (K otkrytiiu podpiski na 1913 g.),’ VO, no. 8–9 (1912).

49 Anderson, Imagined Communities.

50 Staryi Vegetarianets, ‘Po miru,’ VO, no. 9–10 (1911): 52–3. Esfir Kaplan (1889–1933), Iosif Perper’s wife since 1917, was engaged in vegetarian activism in Poltava and the opening of the canteen there. She led the culinary section of The VR and was the secretary of the journal.

51 Staryi Vegetarianets, ‘Po miru,’ VO, no. 4 (1914): 155–6.

52 Cited from: Young, ‘Eating Serials,’ 161.

53 Samuil Perper (1887–1953), a brother of Iosif Perper, was a journalist and a doctor. In addition to popular scientific articles about the benefits of vegetarianism, in The Vegetarian Review he led the regular column ‘Letters from Rome.’ In Soviet times, Samuil Perper was accused of Zionism, sent to Siberia where he perished. See Perel’shtein, 183–6.

54 Iosif Perper, ‘Beseda s chitateliami,’ VO, no. 9–10 (1911): 61–2.

55 ‘Redaktsionnye soobshcheniia,’ VO, no. 9–10 (1911): 62; ‘Redaktsionnye soobshcheniia,’ VO, no. 1 (1914): 40.

56 Iosif Perper ‘Beseda s chitateliami,’ VO, no. 9–10 (1911): 61–2.

57 Howard Williams (1837–1931), an English vegetarian, was an author of the book The Ethics of Diet.

58 L. Perno, ‘Howard Williams,’ VO, no. 3 (1913): 98–100.

59 ‘Pis’mo Khauarda Uil’iamsa,’ VO, no. 4–5 (1913): 171.

60 Goddu, ‘The Antislavery Almanac,’ 143.

61 Iosif Perper, ‘Beseda s chitateliami (K otkrytiiu podpiski na 1913 g.),’ VO, no. 8–9, 1912.

62 For one of many examples, see: ‘Redaktsionnoe soobshchenie,’ VO, no. 1 (1910): 39.

63 From a vast literature, see: Ekström et al, History of Participatory Media.

64 Beetham, ‘Towards a Theory,’ 25.

65 Ibid., 20

66 Young, ‘Eating Serials,’ 23.

67 ‘Redaktsionnye soobshcheniia,’ VO, no. 9–10 (1911): 62.

68 The fragments of letters from Nordman-Severova to Iosif Perper were published serially in VO, no. 6–7, (1914): 215–8; no. 8–9 (1914): 274–7; no. 10 (1914): 315–9.

69 ‘Otryvki iz pisem N.B.N.-Severovoi k I.P. i E.K. [November 1912],’ VO, no. 8–9 (1914): 277.

70 ‘Otryvki iz pisem N.B.N.-Severovoi k I.P. i E.K. [November 1912],’ VO, no. 10 (1914): 315.

71 LeBlanc, ‘Vegetarianism in Russia.’

72 Beetham, ‘Open and Closed.’

73 ‘Golosa chitatelei,’ VO, no. 4 (1914): 154.

74 Ia. Chaga, ‘Pis’mo v redaktsiiu,’ VO, no. 1 (1910): 36.

75 Iosif Perper, ’O sovremennom polozhenii vegetarianstva v Rossii,’ VO, no. 7 (1909): 22–6.

76 ‘Pis’mo v redaktsiiu,’ VO, no. 2 (1910): 34.

77 P. Salienko, ‘Pis’mo krest’ianina k avtoru rasskaza ’Odin protiv vsekh’,’ VO, no. 10 (1909): 31–2.

78 ‘Pis’mo v redaktsiiu,’ VO, no. 4 (1909): 26–7.

79 S. Poltavskii, ‘Pis’mo v redaktsiiu,’ VO, no. 4–5 (1913): 183–5.

80 K. Grekov, ’Nuzhno li eto? (Pis’mo v redaktsiiu),’ VO, no. 5 (1911): 37–8.

81 S. Poltavskii, ‘Koe-chto o ‘krainostiakh’ (Po povodu pis’ma K. Grekova),’ VO, no. 6–7 (1911): 41–4; Ivan Nazhivin, ‘Da, nuzhno!’ VO, no. 6–7 (1911): 44–5.

82 ‘Voprosy i otvety, kasaiushchiesia vegetarianstva,’ VO, no. 4 (1909): 43; A. Georgiev, ‘O zamene kozhi drugimi materialami,’ VO, no. 5 (1909): 34–7.

83 S.O. Perper, ‘Po povodu stat’i ‘O zamene kozhi drugimi materialami’,’ VO, no. 8–9 (1909): 45–7.

84 ‘Voprosy i otvety, kasaiushchiesia vegetarianstva,’ VO, no. 3–4 (1910): 60.

85 ‘Voprosy i otvety, kasaiushchiesia vegetarianstva,’ VO, no. 5 (1910): 40.

86 ‘Golosa chitatelei (Voprosy i otvety, kasaiushchiesia vegetarianstva),’ VO, no. 4–5 (1913): 204.

87 ‘Voprosy i otvety, kasaiushchiesia vegetarianstva,’ VO, no. 9 (1913): 363.

88 ‘Voprosy i otvety, kasaiushchiesia vegetarianstva,’ VO, no. 2 (1915): 79.

89 S. Poltavskii, ‘Pochemu ia stal vegetariantsem,’ VO, no. 5 (1911): 33–5; A. Georgiev, ‘Pochemu ia stal vegetariantsem?,’ VO, no. 9–10 (1910): 57–60; K. Grekov, ‘Kak ia stal vegetariantsem,’ VO, no. 4 (1914): 148–51; L. Kharif, ‘Golosa chitatelei. Pochemu ia stal vegetariantsem,’ VO, no. 3 (1911): 37; V. Boltianskii, ‘Sluchai iz moei zhizni,’ VO, no. 9–10 (1911): 51–2; ‘Tri goda (Kak ia sdelalsia vegetariantsem),’ VO, no. 10, 1912.

90 ‘Golos krest’ianina,’ VO, no. 4 (1911): 24–30.

91 N. Liapin, ‘Pochemu ia stal vegetariantsem,’ VO, no. 3 (1913): 122–3.

Bibliography

Secondary

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1991.

- Beetham, Margaret. “Open and Closed: The Periodical as a Publishing Genre.” Victorian Periodicals Review 22, no. 3 (1989): 96–100.

- Beetham, Margaret. “Towards a Theory of the Periodical as a Publishing Genre.” In Investigating Victorian Journalism, edited by Laurel Brake, Aled Jones, and Lionel Madden, 19–32. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1990.

- Brang, Peter. Rossiia neizvestnaia: Istoriia kul’tury vegetarianskikh obrazov zhizni s nachala do nashikh dnei [Unknown Russia: A history of vegetarian lifestyles from the beginning to the present day]. Moskva: Iazyki slavianskoi kul’tury, 2006.

- Drouard, Alain. “Reforming Diet at the End of the Nineteenth Century in Europe.” In Food and the City in Europe Since 1800, edited by Peter J. Atkins, Peter Lummel, and Derek J. Oddy, 215–225. England, USA: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2007.

- Ekström, Anders, Solveig Jülich, Frans Lundgren, and Per Wisselgren, eds. History of Participatory Media: Politics and Publics, 1750–2000. New York, London: Routledge 2011.

- Goddu, Teresa. “The Antislavery Almanac and the Discourse of Numeracy.” Book History 12 (2009): 129–155.

- Goldstein, Darra. “Is Hay Only for Horses: Highlights of Russian Vegetarianism at the Turn of the Century.” In Food in Russian History and Culture, edited by Musya Glants, and Joyce Toomre, 103–123. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1997.

- Gregory, James. Of Victorians and Vegetarians. The Vegetarian Movement in Nineteenth-Century Britain. London, New York: Tauris Academic Studies, 2007.

- LeBlanc, Ronald D. “Tolstoy’s Way of No Flesh: Abstinence, Vegetarianism, and Christian Physiology.” In Food in Russian History and Culture, edited by Musya Glants and Joyce Toomre, 81–102. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1997.

- LeBlanc, Ronald D. “Vegetarianism in Russia: The Tolstoy(an) Legacy.” The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies, no. 1507 (2001): 1–39.

- Lohr, Eric. Russian Citizenship: From Empire to Soviet Union. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2012.

- Malitska, Julia. “Meat and the City in the Late Russian Empire: Dietary Reform and Vegetarian Activism in Odessa, 1890s –1910s.” Baltic Worlds, no. 2–3 (2020): 4–24.

- Minin, Oleg. “The Value of the Liberated Word: The Russian Satirical Press of 1905 and the Theory of Cultural Production.” The Russian Review 70 (2011): 215–233.

- Neliubina, E.V. “‘Vegetarianstvo est’ soznanie togo, chto zhizn’ prekrasna’ L.N. Tolstoy and I.I. Perper” [‘Vegetarianism is the realization that life is beautiful’ L.N. Tolstoy and I.I. Perper].” In Lev Tolstoy i mirovaia kul’tura. Materialy 2-go mezhdunarodnogo tolstovskogo kongressa, 208–215. Moskva: Institut iazykov i kul’tur im.L. N.Tolstogo, Gos. muzei L.N.Tolstogo, 2006.

- Perel’shtein (Rubman), Tova. Pomni o nikh, Sion [Remember them, Zion]. Ierusalim, 2003. Accessed February 12, 2021. http://www.sakharov-center.ru/asfcd/auth/?t=book&num=1186.

- Shprintzen, Adam. The Vegetarian Crusade: The Rise of an American Reform Movement 1817–1921. University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Thoms, Ulrike. “Vegetarianism, Meat and Life Reform in Early Twentieth-Century Germany and Their Fate in the ‘Third Reich’.” In Meat, Medicine and Human Health in the Twentieth Century, edited by David Cantor, Christian Bonah, and Matthias Dorries, 145–157. London and New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2015.

- Young, Liam. “Eating Serials: Pastoral Power, Print Media, and the Vegetarian Society in England, 1847–1897.” PhD diss., University of Alberta, 2017.

Primary

- Otchet Odesskago Vegetarianskago Obshchestva za 1913 [The Report of the Odessa Vegetarian Society for 1913]. Odessa: Tipografiia Aktsionernogo Iuzhno-Russkogo Obshchestva Pechatnogo Dela, 1914.

- Ustav Kievskago Vegetarianskago Obschestva [The Charter of the Kiev Vegetarian Society]. Kiev: Pechatnia S. P. Iakovleva, 1908.

- Ustav S.-Peterburgskago Vegetarianskago Obshchestva [The Charter of the St. Petersburg Vegetarian Society]. Spb: Tipografiia A.M. Mendelevicha, 1914.

- Vegetariankoe obozrenie, 1909–1915.