Abstract

This article argues that the increasing use of press images around 1900 contributed to the construction of the political persona of the British Statesman Joseph Chamberlain. These images fused scenes from his public and private life and, paradoxically, the new focus on his private characteristics reinforced his public role. His private life did not replace his public side, nor was the private unrelated to politics as celebrity scholarship suggests, but these projected private characteristics widened the scope of what it meant to be a politician in a mass mediated environment. This argument is made through an analysis of the media context in which Chamberlain matured as a politician and the press images of his public and private life. Particularly the many (re)published images of Chamberlain during the ‘media event’ of his death in 1914 are used methodologically to trace the evolution of the visual depiction of politics through time.

The year 1914 is engraved in public memory as the start of the First World War. It also marks the beginning of the ‘modern’ political use of mass media, as wartime governments for the first time employed industrial-scale propaganda.Footnote1 Yet how were the images of the leaders of such governments constructed in these media? And how had this construction of political personae developed during the expansion of mass media in Western countries since the 1880s?

While most scholarship focusses on later twentieth-century political interactions with media including radio and television, some authors have started analyzing the media-political dynamics around the turn of the twentieth century.Footnote2 More specifically, two strands of historical research come to the fore. First, studies showing how the advent of ‘New Journalism’ in the late nineteenth century meant that members of the press increasingly depicted politics in sensationalistic, simplified, and personalized formsFootnote3—yet they focus mostly on the written rather than visual press. Second, a sub literature suggests that these sensationalist and personalized styles led to a particular media focus on monarchs,Footnote4 but does not compare this royal coverage to that of other political figures. These historical studies are complemented by two conceptual and social scientific strands of scholarship. First, the notion of a ‘personalization of politics’ that distinguishes between reporting on a politician’s public and private characteristics, and holds that political coverage increasingly focusses on personalities rather than ‘content’. However, here the historical and visual dimensions remain underresearched.Footnote5 Second, a related literature on ‘celebrity politics’ that includes the idea that the personalized media focus on certain politicians has made them into celebrities.Footnote6 However, here Graeme Turner’s widely-used definition that a ‘public figure becomes a celebrity’ ‘at the point at which media interest in their activities is transferred from reporting on their public role […] to investigating the details of their private lives’Footnote7 is problematic, for it assumes that there is a dichotomy between political and non-political meaning.

This article builds on these sub literatures to show how New Journalism’s visual publications contributed to blending political and non-political meaning in the mediated construction of a non-monarchical political personality around 1900. It does so through the analysis of a media event. The concept of a media event has recently come into use to study the staging of political events. However, such case studies generally focus on the event itself and the sense of simultaneity that its participants experience. In other words, media events have been used to study one moment in time.Footnote8 By contrast, this article uses a media event as a gateway to understand a longer development in time. The chosen event took place also in 1914, but here the year served as an end rather than a beginning: the year of the start of the War also marked the death of the British Statesman Joseph Chamberlain. Chamberlain passed away at the height of the Ulster Crisis, during which Irish Unionists threatened force to resist the implementation of Irish Home Rule.Footnote9 The Irish Question had defined Chamberlain’s political life: his split of the Liberal Party in 1886, leadership of the Liberal Unionists, alliance with the Conservatives, and promotion of imperialism. No politician had done more to oppose Home Rule, and symbolically his final days were marked by his pleas to allies to maintain the fight and not shy away from the civil war he anticipated.Footnote10

Funerals are generally analyzed as media events in the first sense to show the elaborate orchestration of media coverage and how it produced widespread feelings of, for example, national identity. However, a death also creates a moment in which the media reflect on a person and look back on her or his life and career. Here the written reflections are less useful to gain insight into how Chamberlain was portrayed throughout his career, as eulogies are by nature hagiographic. While (the selection of) images can also be suggestive, the images do reflect what he looked like in earlier life and how he was presented in media back then. Thus, even though it is generally not analyzed as such, a death constitutes a specific type of media event that can methodologically shed light on the evolution of the visual depiction of politics through time—both in terms of changing technologies and editorial choices. Namely, Chamberlain’s passing away on July 2nd produced a great volume of images of him in local, regional, national, and international newspapers.Footnote11 While some of these had perhaps not been printed before, many had appeared in the press throughout his career. To emphasize this last point, press articles that were published already during Chamberlain’s career supplement the core corpus of this study.

The methodological choice for Chamberlain is four-fold. First, contemporary journalists described him as one of the most prominent persons in the press at the time,Footnote12 and accordingly there is a wealth of press source material about him. Second, these many images of Chamberlain provide hints about why he became so prominent. Third, despite his exceptional status, he was part of a broader first generation of politicians that featured in the new mass media, and thus an analysis of Chamberlain can shed light on the more general visibility of politicians in the media in his time. Finally, the visual depiction of Chamberlain remains underresearched in an otherwise expansive literature on him. While most biographies focus on his political actions,Footnote13 some already note his elaborate influencing of the press.Footnote14 However, the more specific question of what the new democratic mass public actually saw of Chamberlain is still neglected. Several scholars analyze caricature depictions of him. In interaction with portraits, cartoons—particularly those in Punch—played an important role in making politicians recognizable in the nineteenth century.Footnote15 While Punch moved from radicalism to Unionism like Chamberlain, it eventually became as critical of him as Liberal publications. The frequent depictions of Chamberlain in national satirical magazines such as Punch, Moonshine, and Judy, were in turn often based on those in local Birmingham journals like Dart, Owl, and Crier.Footnote16 However, Chamberlain’s time already constituted ‘the second great age of political caricature’.Footnote17 By contrast, widespread photography and better techniques to print sketches rapidly were new phenomena that could render a politician like Chamberlain visible in novel and more expansive ways, but how exactly?

This article argues that the increasing use of press images contributed to the construction of Chamberlain’s political persona, which fused characteristics and scenes from his public and private life. Paradoxically, a new photojournalistic focus on his private life reinforced his public role. It was not that his ‘real’ private side replaced a former ‘fake’ public side, nor was his private side unrelated to politics as celebrity scholarship might suggest, but that his projected private side widened the scope of what it meant to be a politician in a mass mediated environment. This argument will be made through an analysis of the media context in which Chamberlain matured as a politician and the press images of his public and private life.

Mass Newspapers and a new Focus on the Visual and Personal

Nineteenth-century developments in image production created a ‘visual culture’,Footnote18 including new ways of seeing and a shifting relationship between images and their audiences, particularly around the century’s end.Footnote19 The nineteenth century was also the century of ‘privacy’, yet the distinction between public and private was actually fluid and through visual culture the private became increasingly public.Footnote20 Photographs came to play an important role in this new visual culture, yet only in the late twentieth century did researchers start treating these earlier photographs as ‘historical’ documents that require careful interpretation.Footnote21 While the political role of photographs in the late nineteenth century was complex,Footnote22 photography was already used to reinforce institutional power.Footnote23 More generally, iconic press photos both reinforce and question ideologies and social identities.Footnote24 Such institutional power, ideologies, and social identities were embodied in mediated public personae. These personae already emerged in the form of ‘celebrities’ in the eighteenth century,Footnote25 and in the nineteenth century Queen Victoria and Prime Minister William Gladstone were examples of figures who gained international publicity. However, two factors caused both a quantitative and qualitative change in the reporting on political figures by the end of the nineteenth century: technological developments enabled an exponential growth in the number of (written and visual) media publications, and the commercial New Journalism focussed on personalizing news figures.

Technological improvements both increased the volume and speed of printing, and enabled the widespread distribution of photographs. Over the course of the nineteenth century, the Stanhope iron press, Koenig’s steam press, rotating cylinder press, linotype machine and eventual replacement of steam-powered presses by electrical ones all increased the ability to print newspapers on a greater scale. Stereotyped plates and webs enabled a more flexible newspaper layout in terms of different headlines and the inclusion of images. Moreover, the development of telegraphy in the second half of the nineteenth century—which connected Britain and France by 1850, Europe and America by 1865, and the world by 1903—and railways enabled a much wider collection and distribution of news. Combined with the abolition of newspaper taxes and increasing literacy rates, disposable incomes, and leisure time for reading, these technological advancements created a press revolution in the late nineteenth century. In the UK, the average circulations of the main newspapers rose from 1,800 in 1801 to 2,775 in 1850, and finally to more than 200,000 by 1900. In this year, the first mass newspaper, the Daily Mail that had been established in 1896, even reached a circulation of one million.

Meanwhile, the ability to capture and print images also improved. In 1838, the daguerreotype was invented, followed by the calotype in 1841, colour photography in 1861, dry plate photography in 1877, and celluloid photography in 1888. A crucial development in particular was George Eastman’s introduction of the Kodak hand camera in 1886, with which anyone could take photos in any circumstances—and by 1895 he produced 600 of them per day. The 1880s also marked the decade in which intermediate tones came into use in Britain to print images directly rather than drawing them first. However, the processing and printing was still time consuming and thus unsuitable for the fast distribution of daily news. Only around the turn of the twentieth century did images become more prominent in the dailies, and in 1903 the first photo newspaper, the Daily Mirror, was finally established.

During these decades, competition in this expanding press market meant that editors and journalists needed to find new ways to attract readers, which they partly achieved through a new focus on human interest. This focus of the New Journalism included a switch from a chronological to a narrative style of reporting, and the introduction of the interview format. Moreover, newspapers now included an increasing number of images, which also popularized the expanding sports and entertainment sections. Besides, images that had first appeared in news sections were later remediated by these papers in the form of advertisements or cartoons. Finally, within this environment of increasing competition for readers’ attention, newspaper objects also attempted to style themselves in increasingly mediagenic ways.Footnote26

In all, the ‘industrialization’ of the mass press in the late nineteenth century, coupled with an increasingly personalized style of reporting, presumably also had an impact on how a new mass audience ‘consumed’ politics. Political stories and images no longer solely reached elites, but wide readerships, and the improving possibilities to print photos meant that readers could see political figures ‘in action’ rather than merely statically portrayed as on the older cartes de visite. Photographs were the ultimate form of personalizing news, but rather than offering more realistic depictions of their subjects, the choice and framing of these images reinforced the formation of ‘constructed’ personae, which with such high volumes of publications could be imprinted in readers’ minds on a grand scale. Chamberlain, as a politician whose career peaked in these decades of a revolutionizing mass press, constitutes a telling example of how such a persona was constructed.

The Visualization of Chamberlain’s Public Life

While early photography and printing had allowed political figures to be portrayed only in a posed and static manner, the evolving mass press enabled politicians of Chamberlain’s generation to become present in print more dynamically and on a greater scale. The diversity of images of both public and private scenes made Chamberlain’s persona multifaceted, but even these public scenes alone enabled readers to experience the breadth of politics. The public photos portrayed him in the form of portraits, campaigning and speeching, and in office as Birmingham mayor, colonial secretary and university chancellor.

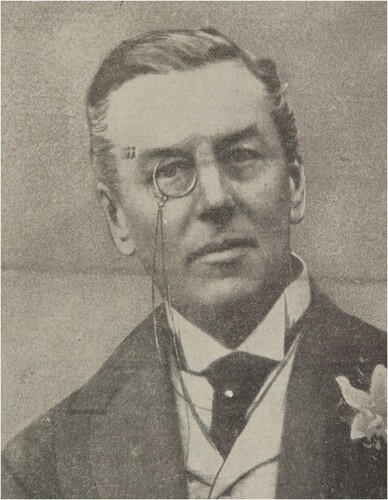

The method of portrayal that showed most continuity with past practice was the portrait. Numerous photos showed Chamberlain’s face from a slight side angle, with his characteristic monocle and orchid in his buttonhole clearly visible,Footnote27 even in the foreign press ().Footnote28 What the Daily Mail labelled as ‘the most popular portrait of Mr. Chamberlain’ was even recycled widely in the press.Footnote29 The monocle provided Chamberlain with an air of expertise and intellectualism, while the showy and exotic orchid—which symbolized virility in ancient Greece—conveyed the image that Chamberlain was special and strong. This monocle and orchid were even so important in making Chamberlain into an easily recognizable public persona that newspapers apparently felt obliged to clarify their absence in some earlier portraits. For instance, the conservative Sheffield Daily Telegraph on 4 July 1914 noted that its depiction of Chamberlain constituted ‘one of the few earlier portraits from which the familiar monocle is absent.’Footnote30 The depictions were no coincidence: Chamberlain had strategically adopted these striking props for caricaturists of Punch and other magazines to identify him for the public.Footnote31

Figure 1. Newcastle Chronicle, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/15.

More generally, the press interest in Chamberlain surpassed his years in national office and went back to his ‘earliest known portrait’ and subsequent ones in 1876, 1886, 1888 and 1891.Footnote32 The interest in Chamberlain portraits continued throughout his life and newspapers later published series of these portraits to trace his visibility through time. The Daily Mail, for example, included five images of him ‘when he first entered public life’, in ‘1871’, as ‘Mayor of Birmingham’, in ‘his favourite portrait’, and as ‘Secretary for the Colonies’.Footnote33 Chamberlain’s career had thus been captured in images over time, and was being ‘replayed’ to the public at the time of his death, which reinforced the idea that he had been a constant factor in politics over the past decades. At this time, the populist Daily Sketch also printed ‘the latest studio portrait’ of him,Footnote34 and numerous other papers reflected with images on when he had been ‘in his prime’.Footnote35 Thus, the visual was used as a cue for marking periods and successes in political work. Importantly, photography both reinforced, and was reinforced by, older forms of this visual dimension such as newspaper sketches. In fact, the Newcastle Daily Journal explicitly mentioned that its portrait of Chamberlain was a ‘sketch from a photograph’ (),Footnote36 and thus shows how media history was an interactive process rather than a linear replacement of old media by the new. The Courier once even commented that Chamberlain actually looked ‘a good deal more like his caricatures than his photographs’, particularly those in Punch rather than in the Westminster Gazette.Footnote37 The ‘original’ written press in turn recommunicated such satires of Chamberlain as appeared in Punch.Footnote38

Figure 2. Newcastle Daily Journal, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/15.

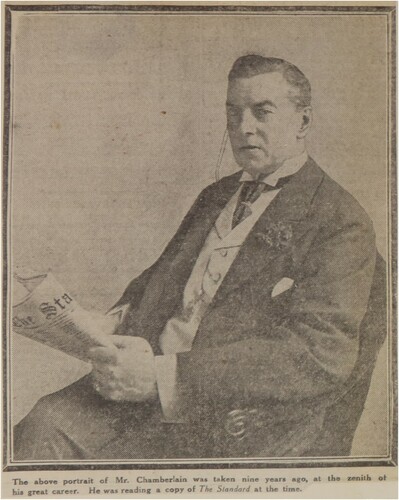

In the press portraits, Chamberlain’s persona was broadened through the inclusion of images of him in different guises, such as when the Daily Mirror included an image of him in his privy councillor’s uniform from behind, holding his arms behind him and staring into the distance.Footnote39 Moreover, headlines above the images actively framed his persona in different ways, such as ‘the fighter’, ‘world figure’ and ‘great leader, statesman and patriot’.Footnote40 Other papers included captions that described him as ‘famous’,Footnote41 which thereby already contributed to portraying him as a personality that was no longer political only in a narrow sense. However, at the same time newspapers reinforced the political meaning of Chamberlain’s persona by emphasizing his embodiment of the British Empire. This connection was partly logical, given that he had served as colonial secretary, but in the press his persona became identified with imperialism overall through titles above portraits that framed him as a ‘great imperialist’ and ‘apostle of empire’.Footnote42 This political dimension of the portraits was finally reinforced by formally referring to him as the ‘Right Hon.’ Joseph Chamberlain.Footnote43 Chamberlain of course held this title, but editors’ choices to mention it explicitly contributed to strengthening his image of a statesman. Finally, the mass press inserted itself as a player of importance in politics in its depictions of a political persona like Chamberlain. Different newspapers namely showed him with a newspaper, suggesting that news consumption constituted an important aspect of what it meant to be a politician. The Evening Standard, for example, depicted the statesman as seated with a copy of the unionist Standard in his hands, while the Manchester Courier used the same photograph but with the title of the newspaper whited out—thus trying to prevent a competitor from using a political message for commercial advertising ().Footnote44

Figure 3. Evening Standard, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/15.

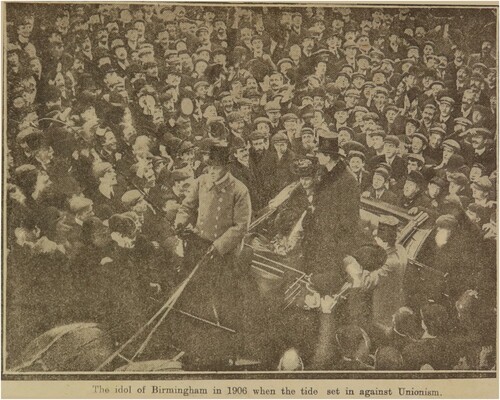

While the portraits and their framing thus already created a multifaceted persona out of Chamberlain, the new ‘action’ photography and fast printing of images of his political actions reinforced this diversity. Images of him amidst crowds, for example, promoted his reputation as a modern democrat—who reached out to the mass public—rather than a traditional aristocrat. Speeches to audiences during election times constituted the most directly ‘political’ of such visualized events. For instance, in 1900 even the German high-circulation Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung (BIZ) featured a full-page image of Chamberlain giving a campaign speech at the Carlton Theatre in London.Footnote45 Similarly, a photograph of Chamberlain speaking from a carriage to a crowd of voters encircling him during the 1906 general election was (re)published in different British newspapers ().Footnote46

Figure 4. Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/14.

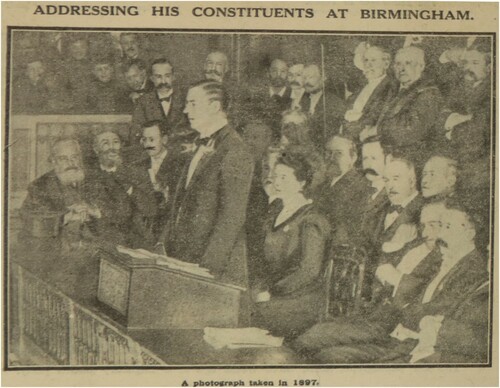

Images also captured Chamberlain at a host of other speaking events. For instance, several papers published an 1897 photo of him addressing his constituents at the Birmingham town hall, which bolstered the idea of him as a democrat who was in touch with the people, and for whom communication to these people constituted part of his political life ().Footnote47 Another photograph, taken nine years later, again reinforced this idea, as Chamberlain was shown getting into his car to tour amongst his constituents to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of his election for West Birmingham. While the Nottingham Guardian published this image with a brief subscript in hindsight, the Manchester Courier added a more elaborate subscript in which it contextualized the situation. Besides the direct event, it noted that the photograph showed ‘Mr. Chamberlain as he appeared just before the seizure which ended his political career’ and that ‘not many days afterwards he was stricken down by the illness from which he never recovered’.Footnote48 Besides showing how an image could be framed differently, this example shows how the political became infused with a private dimension in the form of the allusion to Chamberlain’s subsequent illness. Images also made the parliamentary side of Chamberlain’s persona more visible to the public. For instance, he was depicted ‘in action’ as he addressed the House of Commons as colonial secretary in 1903, and as he took the oath during his last appearance in the Commons as a member of the opposition in 1911.Footnote49 This second image again included an emotional dimension, as he was ‘supported’ by his son Austen and another colleague. It thus showed the influence of Chamberlain’s private life—his illness—on his political work, and thereby shifted his persona as one of a strong and at times divisive politician to one of a more vulnerable public figure with whom a reader might have empathy. Finally, papers showed Chamberlain giving talks that were less directly ‘political’ in that he did not address constituents or parliamentarians, but broader audiences such as at the Guildhall in London or St Andrew’s Hall in Glasgow, which at the same time showed that such presentations also constituted part of his more general political work.Footnote50

Figure 5. Daily Mail, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 3/13.

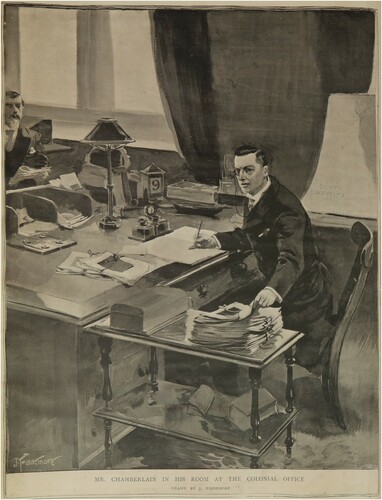

Besides Chamberlain’s public speeches, many press images show him in the functions that he held throughout his career. Already in 1874, the Bee-Hive, which called itself ‘the people’s paper and organ of industry’, featured a large sketch of Chamberlain as the mayor of Birmingham, a theme that also reappeared in the visual depictions published upon his death.Footnote51 A later press image then showed him ‘in his room at the colonial office’ ().Footnote52 This photograph also illustrates the transformation in visual representation between the times that Chamberlain was mayor and colonial secretary: the mayor images had still been of the traditional portrait style, whereas the latter image showed him while he was actively at work. The news consumer could now observe him at his heavy desk while he grabbed folders from a large pile and signed off on documents, while a civil servant was delivering additional papers. The citizen thus gained a personal insight into the functioning of the colonial office through the visualization of Chamberlain. In some images of Chamberlain’s office, he was not even present himselfFootnote53—but by giving the reader the opportunity to explore Chamberlain’s work environment, she was thus enabled to understand better the political duties of this politician. Thus even without the media figure present, the depth of his persona was reinforced by a photograph of his working life. This trend of showing a politician in his office environment was more widespread, also internationally, as illustrated by the series ‘characters of modern Berlin’ in the BIZ, which usually featured a cover image of a well-known Berlin dignitary at his working desk.Footnote54 Besides mayor and colonial secretary, Chamberlain was frequently depicted in his position of first chancellor of Birmingham University. One notable photograph included him in a ‘distinguished group’ at the university’s opening,Footnote55 while various cropped versions of another photograph of him in his university robes circulated in the press more widely.Footnote56 Even though Chamberlain had never attended university himself, these images added an ‘educated’ dimension to his persona and reemphasized that politics was about more than narrow policymaking.

Figure 6. Publication and date unknown. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/10.

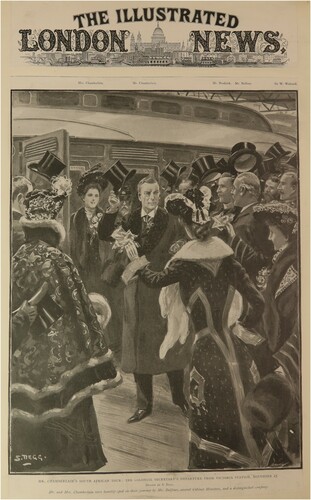

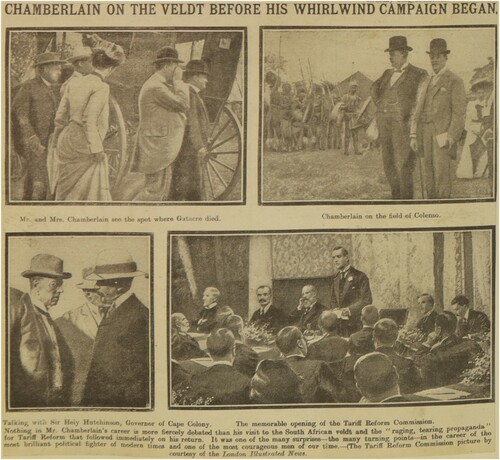

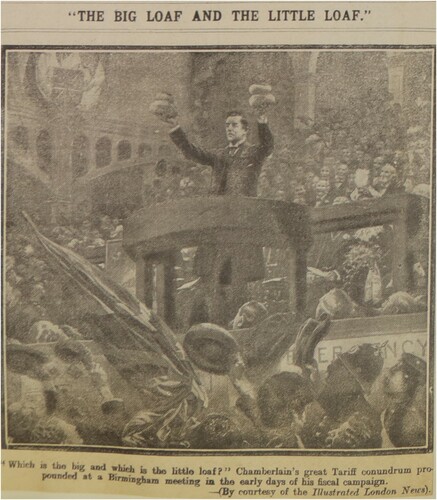

Finally, images captured the more specific policies that Chamberlain pursued, notably with regard to South Africa and tariff reform. For example, one photograph showed him addressing a crowd as he was ‘defending his conduct at Blenheim during the South African War’Footnote57—thus reinforcing the image of him as a modern democrat who sought to legitimate his policies to the new mass electorate. However, Chamberlain received the greatest personal press coverage when he travelled to South Africa for political meetings himself following this War. Through a combination of photographs and sketches, the public could follow his every move to, within, and back from South Africa. For instance, the Graphic showed ‘Birmingham’s good-bye to Mr. Chamberlain’, the Illustrated London News featured his ‘departure from Victoria Station’ on its cover () and another image of his ship ‘leaving Portsmouth Harbour’ inside, the South African News included a photo of the crowd ‘welcoming the Colonial Secretary’ at Port Elizabeth, and the BIZ printed an image of his ‘return from South Africa’.Footnote58 His appearances and meetings in South Africa itself were also widely covered, and an ‘interesting snapshot’ of him getting off a train in Ladysmith and greeting the cheering crowd by raising his hat was reprinted in different cropped versions in numerous papers.Footnote59 The idea that all the press images of Chamberlain made his persona also visually well known was reinforced by a newspaper comment that ‘the illustrious visitor […] was quickly recognised by the crowd’.Footnote60 However, there were also complaints that his new visual appearance conflicted with the image that the public had already created of him. Namely, one article argued that he looked out of place in South Africa and that when ‘one saw pictures of him in the illustrated papers wearing a sun hat and addressing groups of farmers in Bulawayo or Salisbury’ it did not fit with the image of him that had been created in British politics.Footnote61 More generally, many articles noted how scenes of Chamberlain being welcomed in different South African towns were ‘picturesque’,Footnote62 which suggests that the power of images—also in shaping the persona of a politician—was so strong that its discourse also infiltrated the traditional written press. The different types of images that appeared with respect to Chamberlain’s tariff reform campaign, in which he promoted intra-empire trade and which he started soon after returning from South Africa, continued the visualization of his political work (). Images showed the diversity of this campaign work, which included meetings of the Tariff Reform Commission and public speeches in which he emphasized his economic points by showing his audience ‘the big loaf and the little loaf’ of bread that would result from the different policies ().Footnote63 Thus, Chamberlain himself cleverly used visual props, which the press then amplified. Overall, the visualization of Chamberlain’s policy projects fused the political and the personal: through a focus on Chamberlain, the images showed both the diversity of his political persona and the policies that he pursued.

Figure 7. Illustrated London News, November 29, 1902. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 34/3/2/1.

Figure 8. Daily Sketch, July 4,1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/14.

Figure 9. Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/14.

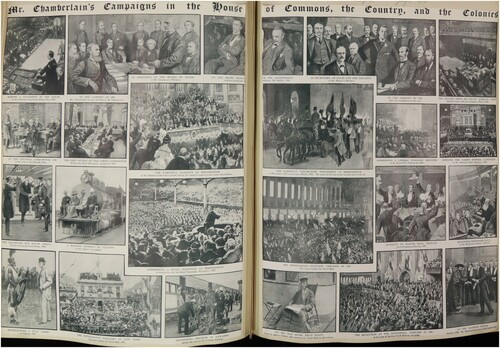

The diversity of Chamberlain’s political activities was so great that, in 1914, the Graphic published a spread on ‘Mr. Chamberlain’s Campaigns in the House of Commons, the Country, and the Colonies’, which included twenty-three ‘action’ images ().Footnote64 This publication reflected how the technical and journalistic changes around the turn of the twentieth century enabled a more varied and wide-scale depiction of a politician like Chamberlain, which shaped his political persona in public. This persona was based in first instance on the visualization of his political work, which included portraits, public speaking engagements, the representation of the various offices he held, and his endeavours in pursuing specific policies with regard to South Africa and tariff reform. The next section shows how this political representation was enhanced by the visualization of private scenes.

The Private Reinforced the Public

While Chamberlain’s portraits arguably already showed a personal dimension, the visualization that New Journalism and improved printing promoted also focussed more on politicians’ private personalities and lives. However, this private side was not separated from a politician’s political role. Journalists did not have a ‘human interest’ in just anyone: the politician’s public role was a precondition for interest in his personal life. Conversely, the personal stories enhanced this public role. The private showed where the politician came from, the familial support he enjoyed, and how he regained strength and inspiration for his political efforts. Moreover, these private images suggest a transformation in the broader political meaning of the politician’s persona from representing partisanship to embodying British politics more generally.

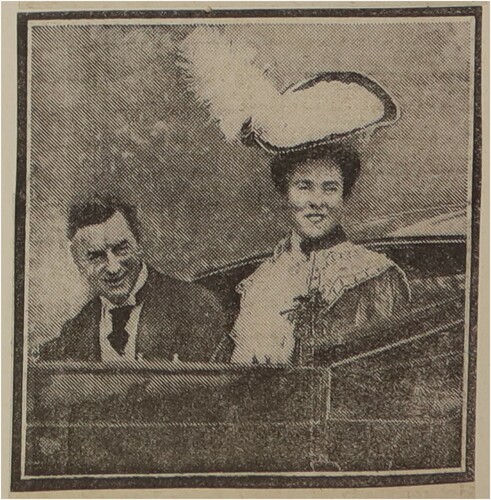

The first recurring object of press images that was both private and political was Chamberlain’s American wife, formerly Miss Mary Endicott. Many publications featured portraits of her, either beside his or alone.Footnote65 Similar to her husband, the new ability to print ‘action’ photographs in the daily press also enabled the depiction of her in different outdoor settings.Footnote66 However, his wife also appeared as his main source of support in his political endeavours. In this context, the Daily Mirror published a large image of him speaking publicly with his wife seated by his side. In the subscript, it quoted Chamberlain’s comment that his wife ‘“has sustained me by her courage and cheered me by her gracious companionship, and I have found her my best and truest counsellor”’. It added that Chamberlain’s ‘power over the audiences of Birmingham was wonderf[ul] but he confessed to his personal friends that he always felt more at home on a pla[tform] when his wife was present. Her presence leant him a splendid moral strength [and] was reflected in the power and eloquence of his speeches.’Footnote67 While this ‘supportive’ role was of course gendered, the image and accompanying text do illustrate how Chamberlain’s private life mixed with his public duties, and how his wife became part of his political persona as well. This idea was reinforced by the fact that, in the visualization of public appearances, Chamberlain was often accompanied by his wife, also in later age ().Footnote68 Finally, the American identity of Chamberlain’s wife reinforced the ‘modern’ and ‘democratic’ air of his political persona, as well as the association between Chamberlain and international politics.

Figure 11. Daily Mail, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/14.

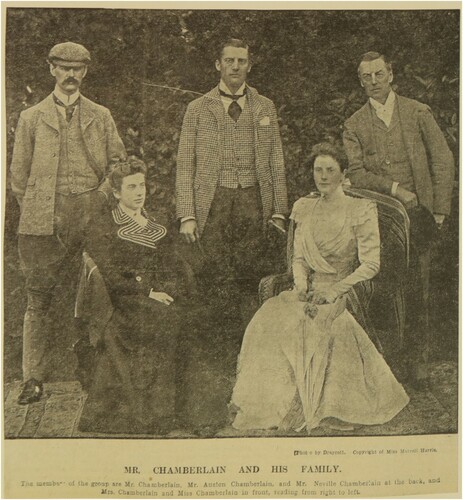

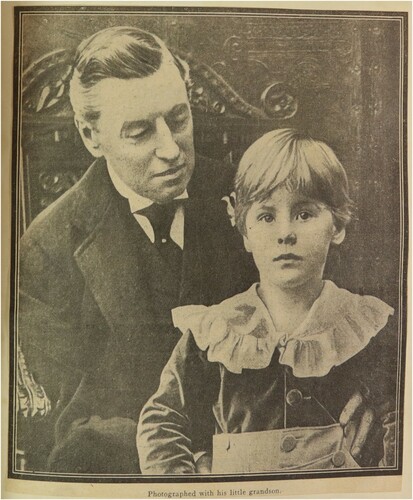

Chamberlain’s wife was not the only family member to feature in press images. Moreover, while this inclusion of relatives added a familial dimension to Chamberlain’s persona, it also popularized his role as a politician. In a 1903 article on Chamberlain, the conservative Pall Mall Gazette reflected on the importance of a politician’s personality and ‘home life’, and gave the early example of how ‘a photograph of Mr. Gladstone with a granddaughter upon his knee was worth thousands of enthusiastic votes to the Liberal Party’.Footnote69 While it is impossible to actually calculate the political impact of family photos in terms of votes, it is plausible that Chamberlain benefitted even more from this evolving media-political dynamic, given that his career peaked slightly after Gladstone’s. Numerous newspapers printed photographs of Chamberlain and his wife with their sons Neville and Austen, daughter Ida, and grandchildren Joe (‘Joey’) and Diane ().Footnote70 Some of these focussed specifically on Chamberlain with one of these family members, such as photos of him and Ida together,Footnote71 or him and his grandson ().Footnote72 Following Chamberlain’s death, the press capitalized on these family ties to dramatic effect. For example, the Daily Mirror published a photo of Chamberlain’s grandson with a little wheelbarrow, entitled ‘LOST HIS GRANDFATHER’.Footnote73 The paper thus infused the legacy of Chamberlain’s persona with a strong emotional dimension. Finally, the distinctiveness and recognizability of Chamberlain’s persona was reinforced by the fact that his son Austen also featured in sketches and photographs wearing his father’s characteristic monocle.Footnote74 Overall, many of these papers printed particular croppings of the same family images, which suggests that even though the number of different press photographs of Chamberlain’s family remained limited, they did reach a wide audience.

Figure 12. Manchester Guardian, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/14.

Figure 13. Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/13.

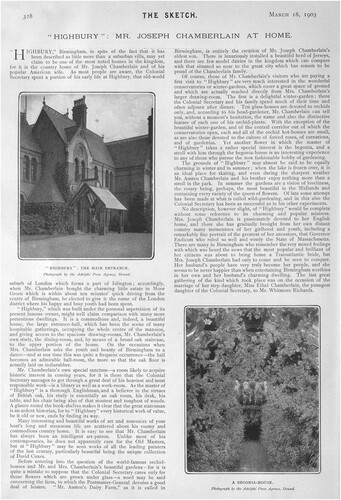

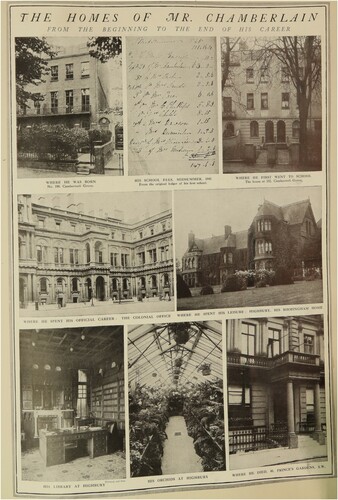

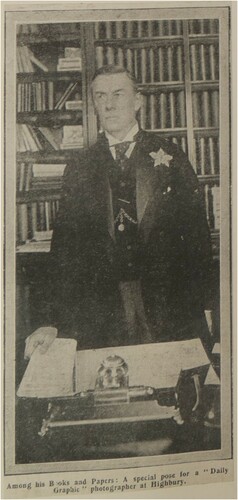

In addition to Chamberlain’s family, a prominent theme that featured in images was his Highbury home at Birmingham, his political base. Chamberlain’s association with this city, which personified the new industrial working classes of the North, already strengthened his image as a modern democratic outsider who challenged the power of the traditional elites in London. Yet his home itself also blended in with his public life, as it served as a backdrop for photographic portraits.Footnote75 Moreover, the grand mansion, which was photographed from various angles and featured across publications,Footnote76 provided Chamberlain’s persona with informal stature. The estate radiated power and influence, especially as it was usually photographed from ground level and thus bore an imposing appearance. It was like a castle from which he fought his political battles. Some publications also showed the reader the central hall inside, or even dedicated an elaborate article to Highbury itself.Footnote77 Moreover, just as sketched portraits of Chamberlain were sometimes based on a photograph, some newspapers included a ‘pen drawing from a photograph’ of Highbury, which again shows the interaction between different imaging techniques.Footnote78 An important part of Highbury that also appeared in many publications was Chamberlain’s personal study: a stately room with his home desk, lined with books.Footnote79 One photograph zoomed in on Chamberlain standing behind his desk himself, and its caption read: ‘Among his books and papers: a special pose for a “Daily Graphic” photographer at Highbury’ ().Footnote80 The comment thus also gives an insight into the interaction between politician and press itself. Photos of Chamberlain and his home were not a natural occurrence, but the outcome of a willingness of the politician and photographer to engage with each other in order to produce a certain persona of Chamberlain in public. More generally, both this personal image and the generic ones of the study conveyed—like the monocle—a sense of erudition and reflection, and thus created the image of a politician whose arguments and policies were grounded in scholarship. Finally, the fact that newspapers included additional images of Chamberlain reading in which it was not clear whether this was at his work or home,Footnote81 reinforces the idea that the distinction between public and private blurred. The images simply gave the impression that all personal learning stood in function of Chamberlain’s public service.

Figure 14. Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/13.

Yet the home also had a more indirect relationship with Chamberlain’s political work: it was presented as a place of rest and recuperation. Especially within the context of increasing leisure time and the popularization of the notion of vacation among a broader public, readers could presumably relate to newspapers’ depiction of Chamberlain’s opportunities for relaxation. These papers included photos of his begonia house and particularly his orchid house, which they described with captions like ‘Mr. Chamberlain’s play’ or ‘his hobby: one of the famous orchid houses at his home at Highbury’ ().Footnote82 The passion for gardening among the British middle classes presumably made them a receptive audience for these photos. However, Chamberlain’s gardening was not presented as mere play or hobbyism: as with the study, his garden houses were a place for reflection that would strengthen his spirit so that he could re-enter the political arena and face the burdens of public life. This leisure at home was finally reinforced by outings abroad. Press photographs showed Chamberlain ‘on holiday in Madeira’ and during ‘a visit to the Pyramids’.Footnote83 While these images promoted the idea that politicians needed to reenergize for politics, they also infused Chamberlain’s persona with a sense of ‘worldliness’. As a self-made businessman rather than an aristocrat, Chamberlain had always faced an uphill battle in proving that his sophistication was not inferior to that of traditional elites, but these photographs at least gave him the image of a man with experience abroad—a characteristic that was not unimportant for a statesman dealing with international affairs.

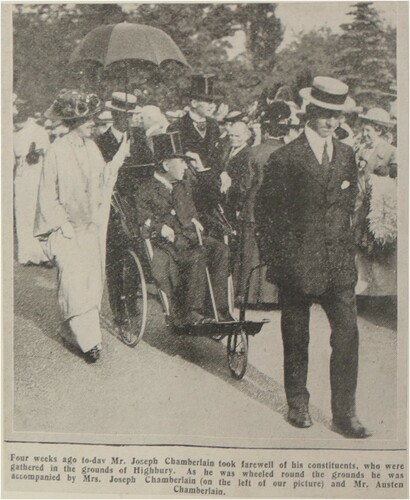

In addition to personal images of his time in office, newspapers included ones related to his early and late life, which suggests that the interest in Chamberlain went beyond his time in office. On one extreme were images of both the house where he was born in Camberwell Grove and the house where he died in Prince’s Gardens, and numerous newspapers juxtaposed these London homes of his beside each other. In addition, publications featured photos of his school.Footnote84 Yet while papers even included photos of the room in which Chamberlain was born, none of the researched newspapers provided an image of Chamberlain at any of these places himself. Thus, while the press showed a keen interest in the background of a well-known politician, it certainly did not receive unlimited access to his life. Besides, in his earlier life, technologies had not yet been as developed and there had not yet been a reason for any journalists to cover him—reinforcing the idea that press interest in a politician was always still tied to her or his political function. However, by the end of Chamberlain's active career, technologies had improved and he had become a prominent politician, and thus the press continued to follow him. Even the BIZ covered his seventieth birthday in 1906,Footnote85 and photographs emerged in the British press of his frequent visits to Cannes over the next years, where he went for his health.Footnote86 Some of the latter already showed him in a wheelchair, and additional photographs depicted how he was being assisted upon his return, as well as when he went out from his London home ‘to take the air’.Footnote87 While this coverage indeed matched New Journalism’s focus on human interest reporting, it also suggests a transformation in the political role that Chamberlain played in the press. He was no longer campaigning or governing, but precisely for that reason the photographs now had a more generic political connotation. Having left active politics, Chamberlain’s persona in a sense transcended partisanship and became a national political symbol in his old age. This idea is finally reinforced by his last public appearance at Highbury on June 6th, 1914. While the Birmingham Daily Mail still labelled this photographed event a ‘Unionist garden party’,Footnote88 other papers presented it as a more general ‘farewell to his constituents’ ().Footnote89 Chamberlain thus no longer just represented a selection of voters, but the general democratic public. More generally, all the articles relating to his youth and old age once again show how press imagery of seemingly private issues bolstered the political dimension of his mediated persona.

Figure 16. Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914. Image courtesy of the Cadbury Research Library: Special Collections, University of Birmingham. Item contained in file JC 4/13.

In all, the increasing number of images that circulated in the mass press around 1900 also contributed to giving a more personal dimension to the personae of politicians like Chamberlain. Chamberlain was depicted together with his wife, as a family man, and in the environs of his home. Moreover, these images enabled the public to get a better understanding of where the politician came from and what became of him after his active career. However, this personal dimension always maintained a connection to politics: the private aspects of Chamberlain’s life were shown as standing in function of, or resulting from, his political life.

Conclusion

‘The Right Hon. Joseph Chamberlain: His political life story told in pictures’, the Graphic announced on July 11th, 1914.Footnote90 Not only the diversity of Chamberlain’s political activities, but also the public and private dimensions of his persona were reflected in collections of press images. Such collections already appeared by 1902,Footnote91 but his death sparked a new wave of publications on the various events and places of his career ().Footnote92 All these publications that the ‘media event’ of his death produced have enabled this article to address four scholarly lacunae: (1) the visual dimension of New Journalism; (2) the impact of New Journalism’s sensationalism and personalization on politicians rather than monarchs; (3) the historical and visual dimensions of the personalization of politics; and (4) the supposed dichotomy between public figures and non-political celebrities. The article has shown that politicians like Chamberlain have a ‘persona’ that is constructed within a media ensemble. This construction did not only take place through the written press, which was the first form of mass media around the turn of the twentieth century, but also through visual publications. While earlier political figures had already been portrayed visually as well, the combination of expanding mass newspapers and improving photographic and printing technologies enabled politicians of Chamberlain’s generation to become visible to a mass audience for the first time in history. Whereas the literature generally assumes that press images have either a public or private focus, this study demonstrated that public and private cannot be separated. A public figure does not transform into a celebrity, but can receive celebrity press attention that remains interconnected with her or his public function. The press sketches and photographs of Chamberlain showed how their public and private aspects fused in their formation of his persona. Paradoxically, the more the images showed of his private side, the more public he became—though over time their precise political meaning also shifted. Given this false dichotomy between public and private in personalization and celebrity studies, it makes more sense to understand the mediated construction of figures like Chamberlain as that of ‘political personae’. It is this notion of political personae that is relevant in understanding better the styling and perception of political figures both in the past and present.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Martin Kohlrausch, as well as the editors and anonymous reviewers, for their insightful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Betto van Waarden

Betto van Waarden, Unit for Media History, Department of Communication and Media, Lund University, Box 117, Lund 221 00, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1 Nelson Ribeiro et al., World War I and the Emergence of Modern Propaganda.

2 Dominik Geppert, Pressekriege; Frank Bösch, Öffentliche Geheimnisse; Chandrika Kaul, Reporting the Raj; Simon Potter, News and the British World; Gunda Stöber, Pressepolitik als Notwendigkeit; Dwayne Winseck and Robert Pike, Communication and Empire; Betto van Waarden, Public Politics; Betto van Waarden, Demands of a Transnational Public Sphere.

3 Andrew Griffiths, The New Journalism, the New Imperialism and the Fiction of Empire, 1870-1900; Joel Wiener, Papers for the Millions; Kate Campbell, W.E. Gladstone, W.T. Stead, Matthew Arnold and a New Journalism; Kate Jackson, George Newnes and the New Journalism in Britain, 1880-1910.

4 Martin Kohlrausch, Der Monarch im Skandal; John Plunkett, Queen Victoria; Miriam Schneider, The “Sailor Prince” in the Age of Empire.

5 For a useful overview, see P. van Aelst, T. Sheafer and J. Stanyer, The Personalization of Mediated Political Communication, in particular 215; Ana Inés Langer, The Personalisation of Politics in the UK, 1–14.

6 The foundational study: P. David Marshall, Celebrity and Power; and for a useful overview: D. Marsh, P. 't Hart and K. Tindall, Celebrity Politics.

7 Graeme Turner, Understanding Celebrity, 8.

8 Daniel Dayan and Elihu Katz, Media Events; Nick Couldry, Andreas Hepp and Friedrich Krotz, Media Events in a Global Age.

9 A. T. Q. Stewart, The Ulster Crisis.

10 Peter Marsh, Joseph Chamberlain, 663–6.

11 See also Joseph Chamberlain Papers, Funeral, Etc., 1914, JC 4/13-16, University of Birmingham Library (UBL).

12 E.g. “Chamberlain,” Reichsbote, March 13, 1900; “‘Joe’,” Hull Weekly News, July 4, 1914; “Current History in Caricature,” Review of Reviews, January, 1902, 16–21, 18; “Chamberlains Abgang,” Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, 1903/39, 616.

13 There is a wealth of biographies on Chamberlain, but the classic and most extensive (though biased) is J. L. Garvin, The Life of Joseph Chamberlain; the most authoritative modern one is Peter Marsh, Joseph Chamberlain.

14 Notably Stephen Koss, The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain, 453–91; A. N. Porter, The Origins of the South African War.

15 Henry Miller, Politics Personified, 13.

16 Ian Cawood and Chris Upton, Joseph Chamberlain and the Birmingham Satirical Journals, 1876–1911, 196–7, 200, 205; P. Vervaecke, La “caricature au vinaigre,” 44; for examples of such caricatures, see also www.punch.co.uk, “Joseph Chamberlain.”

17 Ian Cawood and Chris Upton, Joseph Chamberlain and the Birmingham Satirical Journals, 1876–1911, 176.

18 Vanessa Schwartz and Jeannene Przyblyski, Visual Culture's History, 3.

19 Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer; Jonathan Crary, Suspensions of Perception.

20 Vanessa Schwartz and Jeannene Przyblyski, The Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture Reader, 339–92.

21 John Carter, The Trained Eye, 56–7.

22 See e.g. Elizabeth Edwards, Photographic Uncertainties.

23 John Tagg, The Burden of Representation.

24 Robert Hariman and John Lucaites, No Caption Needed.

25 Antoine Lilti, The Invention of Celebrity; Fred Inglis, A Short History of Celebrity.

26 Asa Briggs and Peter Burke, A Social History of the Media, 105-71, 305-9; Jane Chapman, Comparative Media History, 43–81; Theo Luykx, Evolutie van de Communicatie media, 249–316; Alan J. Lee, The Origins of the Popular Press in England, 1855-1914; C. A. Bayly, The Birth of the Modern World, 1780-1914, 451–87; Jean Chalaby, The Invention of Journalism.

27 E.g. “Mr. Joseph Chamberlain,” Leicester Mail, July 4, 1914; “Death of Mr. Joseph Chamberlain,” Midland Telegraph, July 3, 1914; “Death of Mr J. Chamberlain,” Glasgow News, July 3, 1914; “Mr. Joseph Chamberlain,” Newcastle Chronicle, July 4, 1914.

28 E.g. “Allerlei vom Tage,” Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, 1899/31, 2.

29 “The Greatest of Englishmen,” Daily Mail, July [04], [1914]; also recycled e.g. in “Mr. Joseph Chamberlain,” Glasgow Record, July 4, 1914; “The Late Mr. Joseph Chamberlain,” Western Mail, July 4, 1914; “Death of Mr. Joseph Chamberlain,” Irish Times, July 4, 1914; Liverpool Daily Post, July 4, 1914; “Death of Mr. J. Chamberlain,” Leeds Mercury, July 4, 1914; “The Late Mr Joseph Chamberlain,” Midland Evening News, July 3, 1914.

30 Sheffield Daily Telegraph, July 4, 1914; also “The Dead Statesman,” Sheffield Independent, July 4, 1914.

31 Ian Cawood, Conclusion, 240.

32 Quote in Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; “Joseph Chamberlain,” Manchester Guardian, July 4, 1914; “Our Portrait Gallery,” Men and Women: A weekly biographical and social journal, June 26, 1886/4; “The Right Hon. Joseph Chamberlain, M.P.,” Municipal Review and Local Government Gazette, July 21, 1888; “The Daily Graphic Gallery,” Daily Graphic, April 30, 1891, supplement.

33 Daily Mail, July 4, 1914; similarly: “Portraits of the Dead Statesman,” Daily Telegraph, July [illegible], [1914].

34 Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914.

35 Sheffield Daily Telegraph, July 4, 1914; “Mr. Chamberlain,” Bristol Times, July 4, 1914; “A Great Statesman's Death,” Leicester Daily Post, July 4, 1914.

36 “The Late Mr Joseph Chamberlain,” Newcastle Daily Journal, July 4, 1914.

37 “Mr. Chamberlain at Beaufort West,” Courier, February 19, 1903.

38 “‘Punch’,” Times, January 15, 1896, 10.

39 Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914.

40 “Chamberlain the Fighter,” Liverpool Echo, July 3, 1914; “A Great Leader, Statesman and Patriot,” Yorkshire Herald, July 4, 1914; “Passing of a World Figure,” South Wales Daily News, July 4, 1914.

41 “Joseph Chamberlain,” Liverpool Courier, July 4, 1914; “Joe at the Zenith of his Fame,” Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914.

42 “The Passing of a Great Imperialist,” Daily Graphic, July [illegible], 1914, 61; “The Passing of an Imperial Statesman,” African World, July 4, 1914; “The Apostle of Empire,” Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; Newcastle Illustrated Chronicle, July 4, 1914.

43 “Popular Idol,” Liverpool Evening Express, July 3, 1914; “The Right Hon. Joseph Chamberlain, M.P.,” Nottingham Guardian, July 4, 1914; “The Right Hon. J. Chamberlain,” Eastern Daily Press, July 4, 1914; “The Late Right Hon. J. Chamberlain,” Western Morning News, July 4, 1914; “‘Joe’ Chamberlain Dead,” South Wales Post, July 3, 1914; “Dublin University's Tribute,” Dublin Evening Mail, July 3, 1914; “The Late Rt. Hon. Joseph Chamberlain,” Western Daily Mercury, July 4, 1914; “Story of his Career,” Irish Independent, July 4, 1914; “A Great Englishman,” Staffordshire Sentinel, July 3, 1914.

44 “Early Life,” Evening Standard, July [4], [1914]; “Rise to Fame of a Great Statesman,” Manchester Courier, July 4, 1914.

45 “Wahltage in England,” Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, 1900/41, cover.

46 E.g. Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914; Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914.

47 “Addressing his Constituents at Birmingham,” Daily Mail, July 4, 1914; “Mr. Chamberlain Speaks, Supported by his ‘Best and Truest Counsellor’,” Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914.

48 “The Passing of a Great Statesman,” Nottingham Guardian, July 4, 1914; Manchester Courier, July 4, 1914.

49 Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914; “Mr. Chamberlain's Last Appearance in the House,” Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914.

50 “Mr. Chamberlain's Reception by the City of London,” Sphere, February 22, 1902, supplement; “A Great Meeting,” Glasgow Herald, July 4, 1914.

51 “The Bee-Hive Portrait Gallery,” Bee-Hive, July 25, 1874, 1; Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914.

52 Joseph Chamberlain Papers, Jameson Raid, 1896-1897, JC 4/10, UBL.

53 “Mr. Chamberlain's Reception by the City of London,” Sphere, February 22, 1902, supplement.

54 See e.g. the 1897 issues of the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung.

55 “The University Builder,” Birmingham Gazette, July 4, 1914.

56 Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914; Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; Sheffield Daily Telegraph, July 4, 1914.

57 Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914.

58 “Chamberlain Day,” Daily Graphic, November 19, 1902; “Mr. Chamberlain's South African Tour,” Illustrated London News, November 29, 1902, cover, 824-5; “Arrival at Port Elizabeth,” South African News, February 12, 1903; “Chamberlains Rückkehr aus Südafrika,” Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, 1903/12, 180.

59 “In his Own City,” Daily Chronicle, July 4, 1914; also Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914; “Apostle of Empire,” Daily Mail, July 4, 1914; Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; “Chamberlain on the Veldt Before his Whirlwind Campaign Began,” Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914; Joseph Chamberlain Papers, Mrs Carnegie's Albums Relating to the South African Tour, 1902-1903. (Paper 1), JC 34/3/2/1-3, UBL.

60 “Mr. Chamberlain's Arrival,” Central Watchman, January 30, 1903.

61 Joseph Chamberlain Papers, Funeral, Etc., 1914. (Paper 25), JC 4/25-4/35/18, UBL.

62 “Mr. Chamberlain,” Star, January 22, 1903.

63 “Chamberlain on the Veldt Before his Whirlwind Campaign Began,” Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914; Daily Express, July 4, 1914; “‘The Big Loaf and the Little Loaf’,” Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914.

64 “Mr. Chamberlain's Campaigns in the House of Commons, the Country, and the Colonies,” Graphic, July 11, 1914.

65 Edinburgh Dispatch, July 3, 1914; Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; “Mrs. Joseph Chamberlain,” Birmingham Daily Mail, July 3, 1914; “Mrs. Chamberlain,” Birmingham Gazette, July 4, 1914; Liverpool Echo, July 3, 1914; Liverpool Daily Post, July 4, 1914; Glasgow Record, July 4, 1914.

66 “Stories of ‘Joey’,” Newcastle Evening Mail, July 4, 1914; Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914.

67 “Mr. Chamberlain Speaks, Supported by his ‘Best and Truest Counsellor’,” Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914.

68 E.g. “Mr. Chamberlain's High Faith,” Daily Mail, July 4, 1914; “Statesman with a Rapier Tongue,” Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; Glasgow Record, July 4, 1914; Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914; “Der gefeierte Chamberlain,” Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, 1906/29, 504–5.

69 Harold Begbie, “Master Workers,” Pall Mall Magazine, November, 1903, 289–96.

70 “Chamberlain as Father and Friend,” Daily Sketch, July 4, [1914]; “Mr. Chamberlain and His Family,” Manchester Guardian, July 4, 1914; Birmingham Dispatch, July [3], 1914; Sheffield Daily Telegraph, July 4, 1914; “The Right Hon. Joseph Chamberlain,” Graphic, July 11, 1914; “Passing of a Great Personality,” Dundee Advertiser, July 4, 1914; “A Great Statesman's Death,” Leicester Daily Post, July 4, 1914.

71 Dublin Evening Mail, July 3, 1914; “Character Sketch,” Review of Reviews, February, 1914, 107–16.

72 “Statesman with a Rapier Tongue,” Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; “The People's Idol,” Daily Mail, July 4, 1914.

73 “Lost his Grandfather,” Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914.

74 Glasgow Record, July 4, 1914; “‘The Searchlight’ Commemorates Mr. Joseph Chamberlain's Silver Wedding,” Searchlight of Greater Birmingham, November 13, 1913, 10–41.

75 “The Dead Statesman 16 Years Ago,” Daily Mail, July 4, 1914.

76 Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914; “Mr. Chamberlain's High Faith,” Daily Mail, July 4, 1914; Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914; Edinburgh Dispatch, July 3, 1914; Glasgow Record, July 4, 1914.

77 “Mr. Chamberlain's Reception by the City of London,” Sphere, February 22, 1902, supplement; “‘Highbury’,” Sketch, March 18, 1903, 328.

78 “Joseph Chamberlain,” Birmingham Gazette, July 4, 1914; while it does not explicitly mention it, this sketch of Highbury also seems copied from a photograph: Manchester Guardian, July 4, 1914.

79 “Mr Chamberlain,” Daily Chronicle, July 4, 1914; “The Homes of Mr. Chamberlain,” Graphic, July 4, 1914; “Joseph Chamberlain,” Birmingham Gazette, July 4, 1914; Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914.

80 Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914.

81 “The Late Mr Joseph Chamberlain,” Glasgow Citizen, July 3, 1914; Daily Mail, July 4, 1914.

82 “‘Highbury’,” Sketch, March 18, 1903, 328; “Mr. Chamberlain's Reception by the City of London,” Sphere, February 22, 1902, supplement; Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914; “The Homes of Mr. Chamberlain,” Graphic, July 4, 1914.

83 Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914; Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914.

84 “Mr. Chamberlain's Reception by the City of London,” Sphere, February 22, 1902, supplement; “A New Force in Politics,” Daily Mail, July [4], [1914]; Manchester Evening Chronicle, July 3, 1914; Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914; “Mr. Chamberlain's Birthplace,” Manchester Guardian, July 4, 1914; “From Our London Correspondent,” Liverpool Daily Post, July 4, 1914; “Mr. Chamberlain's High Faith,” Daily Mail, July 4, 1914; “Mr. Chamberlain's Birthplace,” Evening News, July 3, 1914; “Mr. Chamberlain's London Homes,” Daily Express, July 4, 1914; “Mr. Chamberlain's Birthplace and Where He Died,” Birmingham Daily Mail, July 4, 1914; Daily Express, July 4, 1914.

85 Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, 1906.

86 “Death of Mr. Chamberlain, the Statesman of Empire,” Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; “Joseph Chamberlain,” Liverpool Courier, July 4, 1914; “The Lost Leader,” Yorkshire Daily Observer, July 4, 1914; “Passing of a Great Personality,” Dundee Advertiser, July 4, 1914; “At Cannes in 1911,” Aberdeen Daily Journal, July 4, 1914.

87 Glasgow Record, July 4, 1914; Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914; Daily Sketch, July 4, 1914; “A Great Statesman's Death,” Leicester Daily Post, July 4, 1914.

88 “Mr. Chamberlain's Last Appearance in Public,” Birmingham Daily Mail, July 3, 1914.

89 Daily Graphic, July 4, 1914; Manchester Courier, July 4, 1914; “Mrs. Joseph Chamberlain, ‘My Best and Truest Counsellor’,” Daily Mirror, July 4, 1914; East Anglian Times, July 4, 1914.

90 “The Right Hon. Joseph Chamberlain,” Graphic, July 11, 1914.

91 E.g. “Mr. Chamberlain's Reception by the City of London,” Sphere, February 22, 1902, supplement.

92 “The Homes of Mr. Chamberlain,” Graphic, July 4, 1914; “Mr Chamberlain,” Daily Chronicle, July 4, 1914; Glasgow Record, July 4, 1914; Manchester Dispatch, July 4, 1914; “Passing of a Great Personality,” Dundee Advertiser, July 4, 1914; Manchester Evening Chronicle, July 3, 1914.

Bibliography

- Bayly, C. A. The Birth of the Modern World, 1780-1914: Global Connections and Comparisons. Malden: Blackwell, 2004.

- Bösch, Frank. Öffentliche Geheimnisse: Skandale, Politik und Medien in Deutschland und Großbritannien 1880-1914. München: Oldenbourg, 2009.

- Briggs, Asa, and Peter Burke. A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet. Cambridge: Polity, 2009.

- Campbell, Kate. “W.E. Gladstone, W.T. Stead, Matthew Arnold and a New Journalism: Cultural Politics in the 1880s.” Victorian Periodicals Review 36, no. 1 (2003): 20–40.

- Carter, John. “The Trained Eye: Photographs and Historical Context.” The Public Historian 15, no. 1 (1993): 55–66.

- Cawood, Ian. “Conclusion: Joseph Chamberlain: His Reputation and Legacy.” In Joseph Chamberlain: International Statesman, National Leader, Local Icon, edited by Ian Cawood and Chris Upton, 229–43. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Cawood, Ian, and Chris Upton. “Joseph Chamberlain and the Birmingham Satirical Journals, 1876–1911.” In Joseph Chamberlain: International Statesman, National Leader, Local Icon, edited by Ian Cawood, and Chris Upton, 176–210. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

- Chalaby, Jean. The Invention of Journalism. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998.

- Chapman, Jane. Comparative Media History. Cambridge: Polity, 2005.

- Couldry, Nick, Andreas Hepp, and Friedrich Krotz, eds. Media Events in a Global Age. Abingdon: Routledge, 2010.

- Crary, Jonathan. Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990.

- Crary, Jonathan. Suspensions of Perception: Attention, Spectacle, and Modern Culture. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999.

- Dayan, Daniel, and Elihu Katz. Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1992.

- Edwards, Elizabeth. “Photographic Uncertainties: Between Evidence and Reassurance.” History and Anthropology 25, no. 2 (2014): 171–88.

- Garvin, J. L. The Life of Joseph Chamberlain. 6 [vols. 4-6 by Julian Amery]. London: Macmillan, 1933-1969.

- Geppert, Dominik. Pressekriege: Öffentlichkeit und Diplomatie in den deutsch-britischen Beziehungen (1896-1912). München: Oldenbourg, 2007.

- Griffiths, Andrew. The New Journalism, the New Imperialism and the Fiction of Empire, 1870-1900. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Hariman, Robert, and John Lucaites. No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy. Chicago: Chicago UP, 2007.

- Inglis, Fred. A Short History of Celebrity. Princeton: Princeton UP, 2010.

- Jackson, Kate. George Newnes and the New Journalism in Britain, 1880-1910: Culture and Profit. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2001.

- Kaul, Chandrika. Reporting the Raj: The British Press and India, c. 1880-1922. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2003.

- Kohlrausch, Martin. Der Monarch im Skandal: Die Logik der Massenmedien und die Transformation der Wilhelminischen Monarchie. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2005.

- Koss, Stephen. The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain. London: Fontana, 1990.

- Langer, Ana I. The Personalisation of Politics in the UK: Mediated Leadership from Attlee to Cameron. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2012.

- Lee, Alan J. The Origins of the Popular Press in England, 1855-1914. London: Croom Helm, 1976.

- Lilti, Antoine. The Invention of Celebrity: 1750-1850. Cambridge: Polity, 2017.

- Luykx, Theo. Evolutie van de Communicatiemedia. Brussels: Elsevier Sequoia, 1978.

- Marsh, Peter. Joseph Chamberlain: Entrepreneur in Politics. New Haven: Yale UP, 1994.

- Marsh, D., P. ‘t Hart, and K. Tindall. “Celebrity Politics: The Politics of the Late Modernity?” Political Studies Review 8, no. 3 (2010): 322–40.

- Marshall, P. D. Celebrity and Power: Fame in Contemporary Culture. Minneapolis: Minnesota UP, 2014 [1997].

- Miller, Henry. Politics Personified: Portraiture, Caricature and Visual Culture in Britain, c. 1830-80. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2015.

- Plunkett, John. Queen Victoria: First Media Monarch. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

- Porter, A. N. The Origins of the South African War: Joseph Chamberlain and the Diplomacy of Imperialism, 1895-99. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1980.

- Potter, Simon. News and the British World: The Emergence of an Imperial Press System, 1876-1922. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003.

- Ribeiro, Nelson, Anne Schmidt, Sian Nicholas, Olga Kruglikova, and Koenraad Du Pont. “World War I and the Emergence of Modern Propaganda.” In The Handbook of European Communication History, edited by Klaus Arnold, Paschal Preston, and Susanne Kinnebrock, 97–114. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2019.

- Schneider, Miriam. The “Sailor Prince” in the Age of Empire: Creating a Monarchical Brand in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

- Schwartz, Vanessa and Jeannene Przyblyski, eds. The Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture Reader. New York: Routledge, 2004.

- Schwartz, Vanessa, and Jeannene Przyblyski. “Visual Culture’s History: Twenty-First Century Interdisciplinarity and its Nineteenth-Century Objects.” In The Nineteenth-Century Visual Culture Reader, edited by Vanessa Schwartz, and Jeannene Przyblyski, 3–14. New York: Routledge, 2004.

- Stewart, A. T. Q. The Ulster Crisis: Resistance to Home Rule, 1912-1914. Belfast: Blackstaff Press, 1997.

- Stöber, Gunda. Pressepolitik als Notwendigkeit: Zum Verhältnis von Staat und Öffentlichkeit im Wilhelminischen Deutschland 1890-1914. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2000.

- Tagg, John. The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1988.

- Turner, Graeme. Understanding Celebrity. Los Angeles: Sage, 2014 [2004].

- van Aelst, P., T. Sheafer, and J. Stanyer. “The Personalization of Mediated Political Communication: A Review of Concepts, Operationalizations and key Findings.” Journalism 13, no. 2 (2012): 203–20.

- van Waarden, Betto. “Public Politics: The Coming of Age of the Media Politician in a Transnational Communicative Space, 1880s-1910s.” PhD Dissertation, KU Leuven, 2019.

- van Waarden, Betto. “Demands of a Transnational Public Sphere: The Diplomatic Conflict Between Joseph Chamberlain and Bernhard von Bülow and how the Mass Press Shaped Expectations for Mediatized Politics Around the Turn of the Twentieth Century.” European Review of History: Revue Européenne d’Histoire 26, no. 3 (2019): 476–504.

- Vervaecke, P. “La ‘Caricature au Vinaigre’: Francis Carruthers Gould et Joseph Chamberlain, 1895–1907.” Revue Française de Civilisation Britannique 16, no. 2 (2011): 27–47.

- Wiener, Joel, ed. Papers for the Millions: The New Journalism in Britain 1850s to 1914. New York, 1988.

- Winseck, Dwayne, and Robert Pike. Communication and Empire: Media, Markets, and Globalization, 1860-1930. Durham: Duke UP, 2007.