Abstract

In early nineteenth-century German-speaking Europe, the press was a key cultural forum, in which emotions were discussed in public through newly emerging journalistic practices and discourses. The era of educational reforms created debates about the right kinds of means of cultivating the human. One of the key concepts of these debates was the concept of ‘education of the heart’ (Bildung des Herzens). The searchable collections of German-language newspapers and periodicals, such as the ANNO and digiPress repositories provided by the Austrian National Library and Bavarian State Library, open up new vistas of exploring the material across regional borders and established categories and genres, which provides new insight into the ways in which the press shaped ideas of and discourses surrounding the education of emotions in German-speaking Europe.

Introduction

The early nineteenth century was an era in which education gained importance. The cultivation and education of emotions were one of the key issues for the rising middle-classes both within and outside the early nineteenth-century German states. The expanding print culture had an important role in shaping new vocabularies and ideas on emotions in politically and geographically fragmented German-speaking Europe. However, where the previous scholarship has payed attention to literature as means of educating and learning emotions,Footnote1 the variety of the material published in the press before 1850 has received little attention.

By utilizing the two largest digital repositories of German-language newspapers and periodicals to date, provided by the Austrian National Library and Bavarian State Library,Footnote2 this article explores how one of the key concepts of the time, the ideal of ‘education of the heart’ (Bildung des Herzens) was circulated in the German-language press before 1850.Footnote3 Exploring the use of this phrase in large digitized newspaper repositories sheds new light on the ways in which the phrase became adopted from the learned educated debates of the eighteenth-century academic journals, such as Göttingische Anzeigen von gelehrten Sachen, to the more general language of the daily press and expanding popular literature.

This case study discusses the new possibilities and methodological challenges related to digitized collections of historical newspapers and periodicals in Germany and Austria. It demonstrates how the key word searchability of large German-language newspaper corpora enables a new kind of approach to large datasets, providing new insight into the ways in which concepts such as ‘education of the heart’ moved between different textual genres and publication formats, and evolved in time from the eighteenth century to the mid-1800s. This sheds new light on the entanglement of the history of the press and that of the history of emotions in German-speaking Central Europe.

The History of the German-Language Press

Up until the nineteenth century, German-speaking Europe was an important center for the spread and development of printing technology as well as the largest media market in the world in terms of number of newspapers and journals.Footnote4 Thanks to the mandatory public education system that was introduced in Austria and Prussia as well as in other German states in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the number of literates increased in German-speaking Europe. Consequently, although information of the early nineteenth-century reading habits is still fragmentary, including a great deal of regional variation in the growing literacy rates, it has been estimated that the literary rate increased from about 15% around 1800 to 40% in the 1840s.Footnote5

The various textual aspects of early nineteenth-century culture have been a subject to a body of research already since the 1970s, and scholars such as Rolf Engelsing and Robert Darnton have highlighted it as a period in which reading gained vital cultural, social and political significance as new practices of printing and reading emerged. Thanks to the invention of the high-speed printing machine, the number of printed publications increased significantly especially in the 1830s and 1840s. At the same time reading societies, lending libraries and coffee houses provided new access to newspapers and periodicals. It has been estimated that in the early nineteenth century each copy of a newspaper had about 10 readers, and it was customary that reading societies subscribed to many newspapers at the same time.Footnote6

The circulation of the newspapers and periodicals varied greatly from a relatively small circulation of regionally based intelligence sheets Intelligenzblätter with approximately 1,000 copies to the most widely read newspapers such as Allgemeine Zeitung or Vossische Zeitung that in the 1840s could reach a circulation as high as 9,000–20,000 copies.Footnote7 At the same time, the illustrated Das Pfennig-Magazin der Gesellschaft zur Verbreitung gemeinnütziger Interesse, which was published by the Weber company in Leipzig from 1835 onward, became one of the first German-language publications that reached a mass public with a circulation of 100,000 copies.Footnote8

The research tradition on the German press has emphasized the vast diversity and local character of the press before late nineteenth-century when, after the unification of Germany in 1871, first newspapers with national readership started to appear.Footnote9 The various states of the German Confederation (Deutscher Bund) all had their own regulations for the press. The German-language periodical press was thus centered in different states and free cities, but also regulated by supranational regulations such as the Carlsbad Degrees, which were established in 1819. Despite censorship and economic obstacles, the number of newspapers and periodicals increased from the eighteenth century onwards and new issues came out more regularly. In addition, newspapers and periodicals adopted an important role as mediators of information and producers of knowledge in spite of various censorship measures.Footnote10

The history of the German press has been extensively studied since the late nineteenth century. In addition to the classical general studies of the history of the press,Footnote11 there are many excellent recent studies on the German press from the point of view of media history, cultural media studies, and the German tradition of communication history (Kommunikationsgeschichte).Footnote12 In addition, the history of journalism has investigated the historical actors who worked in the press, focusing on the changing role and self-understanding of early German-language journalists, and on the social structures within which they operated.Footnote13 This includes valuable empirical studies to the social backgrounds of journalists and publishers of the major German-language newspapers.Footnote14 In addition, many specialized aspects of the nineteenth-century press have been investigated, including the history of censorship,Footnote15 individual newspapers such as the Allgemeine Zeitung.Footnote16 In the 1990s and early 2000s, especially, the research tradition of the history of the press has generally been strongly focused on regional studies. For example, the area of Hamburg and north-western Germany have been extensively covered thanks to the research carried out at the institute ‘Deutsche Presseforschung’ at the University of Bremen and the multiple volumes of the book series ‘Presse und Geschichte’ edited by Holger Böning.Footnote17 Also the southern and northern parts of GermanyFootnote18 as well as the Austrian press and the German-language press in Central Europe have attracted attention among historians, as well as linguistics and literary scholars.Footnote19

In addition to the regionally-based approaches to the history of the German press, the existing academic work has tended to focus on different categories of publication formats, such as the newspaper, periodical and intelligence sheet. Moreover, nineteenth-century periodical publications have traditionally been studied in relation to their readership, coming from different population and interest groups. This relates to the fact that in the early nineteenth century a great number of new periodicals emerged, targeting different kinds of audiences and ranging from trade journals and academic publications to youth magazines and women’s journals.Footnote20 Accordingly, for instance, the popular press and the sensational press have been studied very much apart from scholarly journals that addressed the academic readership.Footnote21

The vast volume of the nineteenth-century press explains why the existing studies have selected and framed their focus points so carefully. The breadth of the German-language historical press is overwhelming, and it has been estimated that already before 1830 as much as seven thousand titles were published in the area of present Germany alone.Footnote22 This article suggests that the digitalization of the newspaper material enables not only new access but also new insight into the material that has been under-researched due to its vast volume. This provides new opportunities for looking into the history of the press from a transnational perspective and for discovering new kinds of intertextual networks between different textual genres, conventions, and formats. However, the use of digitized newspaper archives and repositories also raises new types of methodological concerns and challenges, which are illustrated by a case study on the full-text searchable databases of ANNO and digiPress.

Digital Newspaper Archives and Research Methods

Although the German-language historical press had a massive volume in the 19th century, important archival material has also been destroyed, and the extant material is in many ways heterogeneous and fragmented.Footnote23 Because there has been no national digitized collection of German newspapers and periodicals, various libraries, such as the Bavarian State Library or the Berlin State Library, all provide only a selected and regionally biased collection of available material. In the 2010s, international collaboration between memory institutions, such as national libraries and academic communities, has increased, as the data holders are constantly seeking to advance the quality of the digitized collections and to facilitate their use in research.Footnote24 The portal of the German Digital Library, Deutsches Zeitungsportal, is a primer example of this. Launched in October 2021 it is seeking to expand in the future into a comprehensive collection that would include all digitized historical newspapers stored in German cultural and scientific collections.Footnote25 Simultaneously, computer-based methods, distant reading and quantitative methods have attracted new kind of interest among digital history and digital humanities in general.Footnote26

However, although there is an effort to increase exchange and share digitized collections to a wider audience, by creating standards such as the IIIF,Footnote27 the digitization of newspapers in Europe has taken place in various ways in different countries, depending on available technology, resources, funding and terms of collaboration with third parties, such as Google. As a result, although the Deutsches Zeitungsportal is gradually growing its volume, the German newspapers and periodicals are still for the most part available as a scattering of individual collections, provided by libraries in various federal states of Germany. Accordingly, the strong regionality that runs through the academic tradition of the study of the German-language press is interwoven with the political history of Germany and Austria and the ways in which the archives of historical newspapers in these countries have been established, organized, and finally digitized in the course of time.

This study builds on two digital collections that are very different from one another, reflecting the diversity of digital newspaper repositories and the different paces and stages of digitization projects in German-speaking countries.Footnote28 The Austrian ANNO portal of the Austrian National Library contains well over 20 million pages, of which about 90% are available for full-text search. The established ANNO is a uniquely large and supranational historical source corpus that provides a vast variety of material from the rich print culture in Central Europe before and after World War I in many languages and across national borders. The digiPress collection of the Bavarian State Library is considerably smaller, having contained approximately 7.8 million pages in the summer of 2021.Footnote29 The collections partly overlap, especially in the case of eighteenth-century and early nineteenth-century material, but ANNO comprises a substantially larger variety of late nineteenth-century and twentieth-century newspapers and periodicals in various languages. Accordingly, the results of the key word search for the exact phrasing ‘Bildung des Herzens’ showed parallel trends up until the 1830s when the lines took drastically different paths (). However, in both cases, the phrase flourished in the nineteenth century, then vanishing with only few exceptions in the second half of the twentieth century.

TABLE 1 The allocation of search results in the digiPress and ANNO collections in July 2021.

The table above is illustrative of an important methodological concern related to digitized datasets. Historians such as Tim Hitchcock have drawn attention to the fact that digitalization changes our research practices in ways of which historians should be aware. One key issue is understanding the logic of the archive, how it guides the research project.Footnote30 In the case of the Austrian National Library and the Bavarian State Library, the differing selection of sources of the digitized collections yields drastically different results for the emergence of ‘Bildung des Herzens’ after 1830. Moreover, in addition to being based on selection, the digitization always transforms the source material that should be acknowledged when using these easily accessible but inevitably edited and transformed source material corpora.Footnote31

As old, material newspaper collections are gradually digitized into the new digital format accessible through a graphical user interface, much of this process remains hidden to the users of the portals. Since the methods and accuracy of the Optical Character Recognition (OCR) of digitized newspapers and periodicals are not entirely transparent to the users, there is a risk of relying too heavily on the ‘black box’ process of digitization. This can lead to oversimplified or misleading interpretations of the search results. The effects of the quality of the OCR on the search results are drastic: the quality of the OCR underpins the entire search as the search engine is harnessed to recognize characters used in specific words, phrases, and their combinations. Historical typefaces and language variation make historical documents challenging for OCR packages.Footnote32 The periodicals published before 1850 are particularly prone to OCR errors.Footnote33 Accordingly, corrupted OCR results raise serious methodological concerns about the reliability of research findings.Footnote34

In addition to acknowledging the pitfalls of digital data, researchers have been reminded to be critical towards the research tools that they are using. This includes, especially, newly voiced concern on how search algorithms shape the research based on digitized newspaper archives.Footnote35 The full-text search technologies are a widely used but relatively under-theorized research tool. Only recently there has been discussion on the ways in which aspects such as the design of the interface guide the search process, which always contains some errors that lead to false positives and false negatives. Moreover, one major problem related to key word searchers is the losing of context, such as the textual surroundings of a given article in a newspaper.Footnote36 Historian Bob Nicholson has drawn attention to the fact that full-text search alters our access to historical sources, describing this as a shift from top-down to bottom-up access. Accordingly, as the chosen key words play a crucial role in this approach, researchers should be particularly aware of their pre-understanding projected into the chosen key words.Footnote37

Despite the issues related to the selection of data available for key word searchers and the quality of the OCR, the searchable archives also provide a new type of access to a large set of documents, that would be impossible to go through on paper or on a microfilm. In this study, the key word search has been used to gain an overview of the emergence of the phrase ‘Bildung des Herzens’. A phrase search, created by placing quotation marks around the search terms, gave 430 hits between years 1759 and 1850 in ANNO and 656 hits for 1753–1850 in digiPress.Footnote38 It should be taken noted that phrase searches, which depend not only on the word accuracy of the OCR but also on correct text segmentation, give more inaccurate results than a search for individual words. As the results both in ANNO and digiPress gave remarkably few misinterpretations due to OCR errors, there is reason to believe that the results exclude a large number of false negatives and probably reveal only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to the actual usage of the phrase in the press. On the other hand, the results also contain false positives, as in some cases the wording appeared in the anatomical sense, referring to the formation of the heart muscle.Footnote39 The physical or anatomical sense of the wording was predominantly used in medical trade journals, but general publications, such as the encyclopedic publication Isis oder enzyclopädische Zeitung, used both meanings as well.Footnote40 In other words, the numbers here should be taken with a grain of salt.

The phrase search frames the search in a highly specific manner, meaning that other search options would have provided different results. A search by proximity, for example, with ‘Bildung Herzens’∼ 10 would have given hits for the words ‘Bildung’ and ‘Herzens’ with a distance of no more than 10 words. This would have expanded the search results to include variations such as ‘Bildung des jugendlichen Herzens’[education of the juvenile heart].Footnote41 Furthermore, synonyms and varieties, such as ‘Erziehung des Herzens’ or ‘Veradelung des Herzens’, which were sometimes used in the nineteenth century, are excluded from a search focusing on the dominant form ‘Bildung des Herzens’.

In this case, a distinctive exact phrasing was selected for the key word search, due to a preunderstanding informed by research literature and previous empirical acquaintance with the primary source material. However, the quantitative results do not reveal much about the meaning of this phrase. One of the main challenges of digital media history is the quest to combine methods of close and distant reading and to apply a critical interpretative approach to the study of digital data.Footnote42 The following section aims to approach this task by examining the search engine hits in more detail and by contextualizing them through qualitative analysis.

The Changing Contexts of the Education of the Heart

The phrasing ‘Bildung des Herzens’ emerged in the digiPress and ANNO collections in the 1750s especially in relation to the book Moralische Briefe zur Bildung des Herzens (1759) by Johann Jacob Dusch (1725–1787). Dusch played an important role in introducing the new ideas of Scottish Enlightenment to the German-speaking audience, and in the preface of the book he explicitly expressed his aim of creating literature that would foster the reader’s internal development and cultivate their moral sentiments.Footnote43 The book was written in the form of letters, which was typical for the epistolary novels of the time.Footnote44 In the following decades, the phrase ‘Bildung des Herzens’ continued to be associated above all with the moral education and cultivation of moral sentiments. This was a highly debated theme that was discussed in multiple volumes published in the late eighteenth century and early 1800s.Footnote45

Here, the division between emotions (Gefühle) and passions (Leidenschaften) played an important role. The education of the heart was associated with the cultivation of religious and moral sentiments, where uncontrollable drives and passions, often associated with youth, were to be avoided and molded into more suitable feelings.Footnote46 In many cases, the debates about the cultivation of emotions were directly linked to various school reforms that took place in the German-speaking countries.Footnote47 The early 1800s represented a period in which education gained importance, as new educational conceptualizations and practices emerged. The education reforms were not only related to the changing social structures but also to the changing theories of childhood and youth, circulated and promoted by the expanding print culture.

By publishing reviews on new books and by mediating topical debates, early journals and periodicals adopted an important role in popularizing new conceptualizations and cultural evaluations of emotions for a widening audience.Footnote48 In the late eighteenth century, the phrase ‘Bildung des Herzens’ appeared predominantly in book reviews published in academic journals, such as Göttingische Anzeigen von gelehrten Sachen or Morgenblatt für gelbildete Stände. These academic journals became new forums of scholarly communication and intellectual exchange and connected academics and the educated members of society in various parts of German-speaking Europe.Footnote49

However, the interest in educational issues was not limited to academic journals. The idea of and the antagonism between the education of reason and the heart, introduced by the educational treatises, was very soon popularized by the press and the phrase ‘education of the heart’ was quickly adopted into the language of advertisements to promote and sell various things from children’s books to sheet music and dance lessons.

As a result, the phrasing ‘Bildung des Herzens’ was particularly prominent in the advertisements for children’s books. Since search engines do not make a distinction between advertisements and other content, these advertisements, which were often republished several times, produce a large number of hits in database searches. At the same time, they are able to provide new insight into the role of the press as a forum and mediator of contemporary literary culture, as also demonstrated by this study.Footnote50 As early as 1776, the Wiener Zeitung published an announcement that advertised an almanac ‘oder Neujahrsgeschenk für Kinder zur Bildung des Herzens’.Footnote51 Later, in the 1820s, the book Alwina. Eine Reihe unterhaltender Erzählungen zur Bildung des Herzens und der Sitten und Beförderung häuslicher Tugenden für Töchter von sechs bis zwölf Jahren, which was published by teacher and pedagogue Johann Heinrich Meynier (1764–1825) under the pseudonym Felix Sternau, was advertised widely within and beyond the German states, even in Switzerland, after its publication in 1825.Footnote52

Similar books for girls were also advertised with the idea that reading them would cultivate their morality and chastity.Footnote53 For boys, nature and natural history were often mentioned as means of emotional cultivation.Footnote54 In the 1840s, the phrase had become so popular that even the first widely spread mass-publication of the time, Das Pfennig-Magazin für Belehrung und Unterhaltung used it in its advertisement for the children’s book Die Natur in Bildern by J. A. Pflanz in 1843.Footnote55 This illustrates well how early mass publications were highly engaged with the aim of improving the society and the self.Footnote56 The emphasis on natural history as a means of cultivating the heart derives from the philanthropist tradition of educational thought which was heavily influenced by Rousseau and which dominated the German pedagogical discussion until the rise of neo-humanism in the first decades of the nineteenth century. However, as the advertisement in the Pfennig-Magazin shows, the philanthropist ideas continued to persist in the German debates on education.

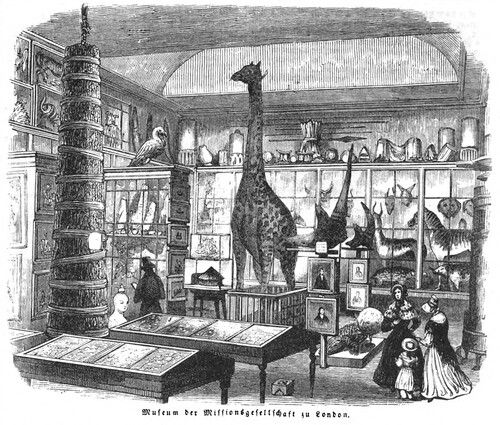

In 1845, another popular publication, the Illustrirte Zeitung, for instance, published an illustrated article on the Museum of the London Missionary Society in London (). The image portrayed a room full of exotic natural historical objects as the accompanied text emphasized the study of nature for the cultivation of the heart and religious feelings. Footnote57 This article is a good example of the ways in which the combinations of images and words were important for the press early on but using key word searches risks neglecting the visuality of newspapers and periodicals.Footnote58 In this case, the image bears special significance because it was copied from the British illustrated journals,Footnote59 providing an interesting case of early nineteenth-century journalistic practices of reprinting international material and adopting it for the German discourse on the cultivation of emotions.

FIGURE 1 Illustrirte Zeitung 29 March 1845. The image has been reproduced by the courtesy of The National Library of Finland.

As historians of emotions have shown, the emotional culture of the German middle-classes required constant care and cultivation, in which not only texts but also other bodily practices played an important role.Footnote60 The key word search for ‘Bildung des Herzens’ offers novel insight into these practices by including material not just from the news and articles, but from the notices and advertisements as well. In addition to nature, and moral tales and narratives, also music and dancing were regarded as something that cultivated the appropriate emotions and social being.Footnote61 Dance teachers could advertise their lessons to the youth by highlighting the benefits of physical training for morality and social interaction, just as Carl August Klemm did in his advertisement in the Leipziger Zeitung, the most widely read newspaper in the eastern parts of the German states, in 1828.Footnote62

The phrase ‘education of the heart’ was so popular in advertisements that the humorous-satirical journal Der Humorist, led by Moritz Gottlieb Saphir (1795–1858), one of the well-known satirist of the time, parodied the verse in the 1840s with the line ‘for the cultivation of the heart, the mind and the printing errors’.Footnote63 More importantly, in the 1840s, especially, the phrase gained new national connotations, as it was more explicitly associated with the ideas of national education (Nationalerziehung) and those of improving not just the self but society as well. For example, already in 1804 the publication Der deutsche Patriot published a book review on a book addressing the role of language in the education of the heart, which was seen as the moral backbone of society.Footnote64 The new contexts of the phrase around the 1848–1849 revolutions, and its appearances in the daily newspapers, suggest a transition to heightened political meanings, and a stronger linkage to national education and the cultivation of Bürger.Footnote65

The new political meanings of education and its linkage to growing nationalism in the early nineteenth century have been addressed from many points of view in previous research.Footnote66

Furthermore, scholars in the field of media history have emphasized the bond between media and nationalist practice in the German lands. For instance, Fichte’s speeches ‘Reden an die deutsche Nation’ gained influence after they appeared in print in 1808. Different forms of printed materials, from nationalistic journals to speeches, patriotic poems, songs and caricatures, took on an important role in strengthening and mobilizing nationalistic sentiments before and during the 1848–1849 revolutions.Footnote67

The press can be approached as an important vehicle which circulated novel ways of understanding the ideal of cultivation of emotions and spread them synchronically across a wide geographical area.Footnote68 This can be linked to the social background of early journalists. As Jörg Requarte has shown, the journalists working in the early nineteenth-century German-language periodical press had a distinctively academic background. Before journalism became professionalized in the second half of the nineteenth century, many academics, schoolteachers, and gymnasium principals worked for the press to earn some additional income on the side of their daily jobs. Because newspapers required correspondents who were educated and understood foreign languages, the social background of early journalists was highly cultivated compared to the main population.Footnote69 In addition, nineteenth-century pedagogues also used periodical publications to publish their ideas on the cultivation of emotions.Footnote70 This means that many of those who consumed the press and contributed to the new medium were also interested in educational matters. Moreover, especially before 1850, the early German-language journalists or Zeitungs-Schreiber approached the ideal of impartiality from a different angle compared to the Anglo-American journalistic tradition. In the German-language press, the ideals of political detachment and objectivity were not as poignant as in the Anglo-American tradition, but the early German journalists emphasized a certain emotional style and the ideal of dispassionate reporting in their attempt to not just observe but also improve the society.Footnote71

The early nineteenth-century German-language press thus not only had vast potential in shaping ideas and evaluations of emotions, but it was itself in many ways shaped by the emotional culture of the middle classes, which was centered around the ideals of emotional constrain and self-improvement. Moreover, the ideal of the education of the heart, which in the late eighteenth century meant above all religious and moral education, gained new secular meanings in the 1840s, as it was increasingly associated with the formation of the nation and the state, which were to be built upon shared collective virtues and emotions. The way of discussing social and political reforms and creating collective identities by emphasizing the internal development of the individual was typical of the early nineteenth-century German discourses that were influenced by the political constraint of the middle-classes in the aftermath of the French Revolution, on the one hand, and the Romantic movement, on the other. ‘Bildung des Herzens’ was thus a distinctively German interpretation of and contribution to the understanding of emotions and moral sentiments, perceived not as inherently natural but as socially learned and cultivated.Footnote72

Conclusions

This article has investigated the concept of the ‘education of the heart’ in two major German-language newspaper repositories, ANNO and digiPress Bayern, provided by the Austrian National Library and Bavarian State Library. The digitized collections that are available for a full-text search allow to trace the concept of the education of the heart in different text types, such as book reviews, articles or advertisements, as well as in various publication types, such as books, intelligence sheets, newspapers or periodicals. Accordingly, the new digital collections enable a novel look into the emotional culture of the German middle-classes, and how this was shaped and sustained by the expanding print culture.

However, the use of digitized source corpora also requires new kinds of source criticism and a pre-understanding of the development of digital newspaper repositories. By focusing on the circulation of the phrase ‘education of the heart’(Bildung des Herzens), this article has shed light on the pitfalls and benefits of key word searchability and its ability to provide the new insights into the German history of the press, which, because of the fragmentation of German collections due to specific historical context, has been strongly focused on local case studies as well as on studies that focus on certain genres or publication types such as intelligence sheets, youth magazines or moral journals.

Although digitization enables a new kind of transnational access and perspective to the under researched early nineteenth-century German-language press, the digital approach also has the danger of neglecting the regional, political, and temporal contexts of individual publications, as it highlights the textual connections between different kinds of text types and publication genres. This means that further and more extensive critical analyses are needed to understand how the textual networks and journalistic practices were involved in the on-going mediation between high and low, elite and popular, across the political and geographical borders of German-speaking Europe.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of the project ‘Blind Zeal or Cultivation of the Heart: Emotions in the Early Nineteenth-Century German-language Press’. It was partly written at the Research Center for the History of Emotions at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, Germany. I thank the members of the Research Center and the anonymous referee(s) for their invaluable feedback.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in ANNO-Austrian Newspapers Online at http://anno.onb.ac.atanddigiPressBayernat https://digipress.digitale-sammlungen.de.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Heidi Hakkarainen

Heidi Hakkarainen, Department of Cultural History, University of Turku, Turku, FIN-20014, Finland. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 See Eitler, Olsen and Jenssen, “Introduction”, 1–20.

2 In Europe, the most large-scale digitization project is the EU-funded “Europeana Newspapers” collection, which also includes German-language material: http://www.europeana-newspapers.eu/.

3 On the nineteenth-century ideal of the “education of the heart”, see further Frevert, “Herzensbildung”.

4 Yet, although the invention of book printing is associated with Gutenberg, the mechanical letterprint was invented in Asia and used in China and Korea already from the 1230s onwards. Bösch, Mass Media, 2, 13.

5 See further Engelsing, Analphabetentum und Lektüre, 61–62, 70, 85; Rintelen, Zwischen Revolution und Restauration, 15–16.

6 See Engelsing, Analphabetentum und Lektüre, 60; Darnton, “History of Reading”, 140–168.

7 Requate, Journalismus als Beruf, 129; Engelsing, Analphabetentum und Lektüre, 60.

8 Engelsing, Analphabetentum und Lektüre, 92–93; Requate, “Kennzeichen”, 38.

9 On the first newspapers with national circulation, see further, e.g. Dussel, Die Deutsche Tagespresse, 86–91; Fritzsche, Reading Berlin 1900, 47, 53.

10 On censorship and the emergence of newspapers and periodicals in German-speaking Europe, see further Stöber, Deutsche Pressegeschichte, 141–142; Dussel, Die Deutsche Tagespresse, 12–18.

11 Lindemann, Deutsche Presse bis 1815; Koszyk, Deutsche Presse.

12 See e.g. Wilke, Grundzüge der Medien- und Kommunikationsgeschichte; Stöber, Deutsche Pressegeschichte; Bösch, Mass Media.

13 Birkner, Selbstgespräch, 17, 20–24, 61–62; Schönhagen, Unparteilichkeit, 1–13.

14 Requate, Journalismus als Beruf; Fischer, Deutsche Presseverleger.

15 See e.g. Guggenbühl, “Zensur und Pressefreiheit”; Wilke, “Zensur und Pressefreiheit”.

16 Blumenauer, Journalismus, 1–2; Rintelen, Zwischen Revolution und Restauration, 377–378.

17 Böning, Periodische Presse.

18 For example, Borst, “Schwäbische Zeitungen”, 101–128; Albrecht and Böning, Historische Presse und ihre Leser.

19 Riecke and Schuster, Deutschsprachige Zeitungen.

20 Böning, Periodische Presse, 11.

21 See especially Dulinski, Sensationsjournalismus in Deutschland, 103–120; Vogel, Die populäre Presse, 31–34.

22 Bösch, Mass Media, 52.

23 Birkner, Selbstgespräch, 65; Birkner, Koenen, and Schwarzenegger, “A Century of Journalism History”, 1123–1126.

24 Kugler, “Automatisierte Volltexerschließung”, 34–35.

25 Accessed 16 November 2021. https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/content/newspaper/ueber-uns.

26 See especially the seminal study of Moretti, Distant Reading, 44–49. On the German case, see Erling and Tatlock, “Introduction”, 1–25.

27 See further the homepage of the International Image Interoperability Framework Community at https://iiif.io.

28 Birkner, Koenen, and Schwarzenegger, “A Century of Journalism History”, 1125.

29 Accessed 21 June 2021. https://digipress.digitale-sammlungen.de.

30 Hitchcock, “Confronting the Digital”, 9–23.

31 See Mussell, The Nineteenth-Century Press, 1–4; Prescott, “Searching for Dr. Johnson”, 51–71.

32 See further Prescott, “Searching for Dr. Johnson”, 51–71.

33 Ibid; Wijfjes, “Digital Humanities”, 19.

34 See Jarlbrink and Snickars,“Cultural heritage”, 1228–1243.

35 Gooding, Historic Newspapers, 1.

36 Huistra and Mellink, “Phrasing History”, 220–229.

37 Nicholson, “The Digital Turn”, 59–73.

38 The results were retrieved by summer 2021, and do change due to the ongoing digitization process.

39 See Weber anatomia comparata nervi sympathici, Heidelbergische Jahrbücher für Literatur Hauptteil 2, 1819.

40 See e.g., “Wahlverwandtschaft zwischen dem sogenannten Naturphilosophen und Supernaturalisten”, Isis oder encyclopädische Zeitung Heft 6, 1827; J.B. Wilbrand, “Vorläufiger Entwurf zu einem natürlichen Pflanzensystem”, Isis oder encyclopädische Zeitung, Heft 9, 1821.

41 Meynier, Louise, “Kinderspiele in Erzählungen und Schauspielen zur Bildung des jugendlichen Herzens”, Zeitung für die elegante Welt, 24 October, 1801.

42 See Wijfjes, “Digital Humanities”, 6–8.

43 Dusch, Moralische Briefe, 17–29.

44 See Kurz and Lange, “Der europäische Briefroman”, 363–370.

45 See e.g. “Ueber die Moral von Jesuiten”, Neueste Mannigfaltigkeiten (4)1780; “Erziehungswesen”, Allgemeiner Anzeiger und Nationalzeitung der Deutschen 4 November 1841.

46 Frevert, “Defining Emotions”, 15–17. See also Bösch, Mass Media, 51–54.

47 For example, “Was hat man von Sittengerichten in öffentlichen Schulen zu halten”, Intelligenzblatt von Salzburg 29 January 1803.

48 For example, “Auszüge aus einem zunächst für Riga geschriebenen Buche”, Berlinische Monatschrift May 1793.

49 Böning, “Deutschsprachige Presse”, 29–48; Haug, “Wisseschaftliche Literaturkritik”, 35–61.

50 Cf. Prescott, “Searching for Dr. Johnson”, 67.

51 Wiener Zeitung, 10 November 1776.

52 For example, Morgenblatt für gebildete Stände, 12 July 1826; “Wegweiser im Gebiete der Künste und Wissenschaften.” Abend-Zeitung, 17 June 1826; Der aufrichtige und wohlerfahrene Schweizer-Bote, 17 August 1826.

53 See e.g. Genersich, Wilhelmine; Senneterre Renneville, Nina.

54 “Der gute Knabe. Ein Bilderbuch für gute Kinder”. Zeitung für die elegante Welt, 29 November 1806.

55 Das Pfennig-Magazin für Belehrung und Unterhaltung (Das Pfennig-Magazin für Verbreitung gemeinnütziger Kenntnisse), 28 January 1843.

56 Requate,“Kennzeichen”, 37–39.

57 “Museum der Missionsgesellschaft in London”, Illustrirte Zeitung, 29 March 1845.

58 See Maurantonio, “Archiving the Visual”, 88–102.

59 Seton, “Reconstructing the Museum”, 98–101.

60 Frevert, “Emotional Knowledge”, 268–269.On the practice, theoretical approach to the study of emotions see Scheer, “Are Emotions”, 193–220.

61 “Ueber Nutzen und Nothwendigkeit sorgsamer Pflege der Musik an Gymnasien”. Jahrbücher des deutschen National-Vereins für Musik und Ihre Wissenschaft, 5 March 1840; “Vom Tanze in diätetischer Hinsicht”. Österreichisches Bürgerblatt für Verstand, Herz und gute Laune, 1 January 1830. See also Lempa, Beyond Gymnasium, 67–194.

62 Leipziger Zeitung, 15 September 1823.

63 “[…] Zur Bildung des Herzens, des Geistes und der Druckfehler”, Der Humorist, 18 November 1849.

64 “Der Einfluß der Sprache auf die Bildung des Herzens. Ein Bruchstück. Von Dr. G.W. Becker”, Der deutsche Patriot. Ein Volksblatt, 3 February 1804.

65 See, e.g., Österreichisches Pädagogisches Wochenblatt zur Beförderung des Erziehungs- und Volksschulwesens, 8 November 1848; Die Presse, 15 September 1848; Wiener Zeitschrift, 23 January 1849; Leipziger Zeitung, 18 Dezember 1849.

66 For example, Vierhaus, “Bildung”, 517, 524, 527.

67 Bösch, Mass Culture, 68–69, 73–76. Cf. Anderson, Imagined Communities, 1–7.

68 Frevert, “Emotional Knowledge”, 268–269.

69 Requate, Journalismus als Beruf, 117–143.

70 For example, Peter Villaume (1746–1825), who published widely on education, published a piece called “Über die Gewalt der Leidenschaften in den Jünglingsjahren” in the Berlin-based periodical Deutsche Monatsschrift in June 1790.

71 Schönhagen, Unparteilichkeit, 27–36; Birkner, Selbstgespräch, 17–22, 367–370.

72 Cf. Reddy, Navigation of Feeling, 180, 208, 155–187.

Bibliography

- Digital Newspaper Collections

- Austrian National Library, Austrian Newspapers Online ANNO.

- Bavarian State Library, digiPress.

- Contemporary literature

- Research literature

- Albrect, Peter, and Holger Böning. Historische Presse und ihre Leser: Studien zu Zeitungen, Zeitschriften, Intelligenzblättern und Kalendern in Nordwestdeutschland. Bremen: Edition Lumière, 2005.

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso, 1991.

- Birkner, Thomas. Das Selbstgespräch der Zeit. Die Geschichte des Journalismus in Deutschland 1605–1914. Cologne: Halem, 2012.

- Birkner, Thomas, Eric Koenen, and Christian Schwarzenegger. “A Century of Journalism History as Challenge. Digital Archives.” Sources and Methods. Digital Journalism 6, no. 9 (2018): 1121–1135. doi:10.1080/21670811.2018.1514271.

- Blumenauer, Elke. Journalismus zwischen Pressefreiheit und Zensur: Die Augsburger “Allgemeine Zeitung” in Karlsbader System (1818–1848). Köln: Böhlau, 2000.

- Böning, Holger. Periodische Presse. Kommunikation und Aufklärung. Hamburg und Altona als Beispiel. Bremen: Edition Lumière, 2002.

- Böning, Holger. “Deutschsprachige Presse in Mittel – und Osteuropa – das Bremer Projekt “Deutsche Presse” von den Anfängen bis 1815.” In Deutschsprachige Zeitungen in Mittel- und Osteuropa. Sprachliche Gestalt, historische Einbettung und kulturelle Traditionen, edited by Jörg Riecke, and Britt-Maria Schuster, 29–48. Berlin: Weidler Buchverlag, 2005.

- Borst, Otto. “Schwäbische Zeitungen und ihre Leser zwischen Spätaufklärung und Gründerzeit.” In Von der Pressfreiheit zur Pressefreiheit. Südwestdeutsche Zeitungsgeschichte von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart, edited by Klaus Dreher, 101–128. Stuttgart: Konrad Theiss Verlag, 1983.

- Bösch, Frank. Mass Media and Historical Change: Germany in International Perspective, 1400 to the Present. New York: Berghahn Books, 2015.

- Darnton, Robert. “History of Reading.” In New Perspectives on Historical Writing, edited by Peter Burke, 140–168. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1995.

- Dulinski, Ulrike. Sensationsjournalismus in Deutschland. Konstanz: UVK Verlagsgesellschaft, 2003.

- Dusch, Johann Jacob. Moralische Briefe zur Bildung des Herzens. Leipzig: Breitkopf, 1759. Digital edition. Accessed 2 January 2020 from Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt. http://digitale.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/vd18/content/pageview/2074754.

- Eitler, Pascal, Stephanie Olsen, Uffa Jenssen. “Introduction.” In Learning How to Feel: Children’s Literature and Emotional Socialization, edited by Ute Frevert, et al., 1–20. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Engelsing, Rolf. Analphabetentum und Lektüre: Zur Sozialgeschichte des Lesens in Deutschland zwischen feudaler und industrieller Gesellschaft. Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler, 1973.

- Erling, Matt, and Lynne Tatlock. “Introduction: ‘Distant Reading’ and the Historiography of Nineteenth-Century German Literature.” In Distant Readings: Topologies of German Culture in the Long Nineteenth Century, edited by Matt Erling, and Lynne Tatlock, 1–25. New York: Camden House, 2014.

- Fischer, Heinz-Dietrich. Deutsche Presseverleger des 18. Bis 20. Jahrhunderts. Pullach bei München: Verlag Dokumentation, 1975.

- Frevert, Ute. “Herzensbildung. Gefühle und Empfindungen. Vom Wandel der Erziehungsideale über die Jahrhunderte.” Humboldt. Eine Publikation des Goethe Institutes. Accessed 7 October 2019. http://www.goethe.de/wis/bib/prj/hmb/the/158/de10438354.htm.

- Frevert, Ute. “Emotional Knowledge: Modern Developments.” In Emotional Lexicons. Continuity and Change in the Vocabulary of Feeling 1700-2000, edited by Ute Frevert, et al., 260–273. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Fritzsche, Peter. Reading Berlin 1900. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

- Genersich, Johann. Wilhelmine. Ein Lesebuch für Mädchen von 10-15 Jahren, zur Bildung des Herzens und des Geschmacks. Doll: Wien, 1811. Accessed 4 January 2020 from ÖNB Bildarchiv und Grafiksammlung http://data.onb.ac.at/rec/AC09891781.

- Gooding, Paul. Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age: “Search All About It!”. New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Guggenbühl, Christoph. “Zensur und Pressefreiheit. Kommunikationskontrolle in Zürich an der Wende zum 19. Jahrhundert.” Dissertation. Zürich: Chronos, 1996.

- Haug, Christine. “Wissenschaftliche Literaturkritik und Aufklärungsvermittlung in Hessen um 1800. Die Zeitschriftenprojekte des Verlagsunternehmens Johann Christian Korad Krieger (1725-1825).” In Zeitung, Zeitschrift, Intelligenzblatt und Kalender. Beiträge zur historichen Presseforschung, edited by Astrid Blome, 35–61. Bremen: Edition Lumière, 2000.

- Hitchcock, Tim. “Confronting the Digital. Or How Academic History Lost the Plot.” Cultural and Social History 10, no. 1 (2013): 9–23. doi:10.2752/147800413X13515292098070.

- Huistra, Hieke, and Bram Mellink. “Phrasing History: Selecting Sources in Digital Repositories.” Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History 49, no. 4 (2016): 220–229. doi:10.1080/01615440.2016.1205964.

- Jarlbrink, Johan, and Pelle Snickars. “Cultural Heritage as Digital Noise: Nineteenth Century Newspapers in the Digital Archive.” Journal of Documentation 73, no. 6 (2017): 1228–1243. doi:10.1108/JD-09-2016-0106.

- Koszyk, Kurt. Deutsche Presse im 19. Jahrhundert. Geschichte der deutschen Presse. Teil II. Berlin: Colloquium Verlag, 1966.

- Kugler, Anna. “Automatisierte Volltexterschließung von Retrodigitalisaten am Beispiel historischer Zeitungen.” Perspektive Bibliothek 7, no. 1 (2018): 33–54. doi:10.11588/pb.2018.1.48394.

- Kurz, Stephan, and Stella Lange. “Der europäische Briefroman: Eine Auswahlbiographie von den Anfängen bis zur 19. Jahrhunderts.” In Poetik des Briefromans: Wissens- und Mediengeschichtliche Studien, edited by Gideon Stiening, and Robert Vellusig, 341–362. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012.

- Lempa, Heikki. Beyond Gymnasium. Educating the Middle-Class Bodies in Classical Germany. Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2007.

- Lindemann, Margot. Deutsche Presse bis 1815. Geschichte der deutschen Presse. Teil 1. Berlin: Colloquium Verlag, 1969.

- Maurantonio, Nicole. “Archiving the Visual: The Promises and Pitfalls of Digital Newspapers.” Media History 20, no. 1 (2014): 88–102. doi:10.1080/13688804.2013.870749.

- Moretti, Franco. Distant Reading. New York: Verso, 2013.

- Mussell, James. The Nineteenth-Century Press in the Digital Age. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Nicholson, Bob. “The Digital Turn: Exploring the Methodological Perspectives of Digital Newspaper Archives.” Media History 19, no. 1 (2013): 59–73. doi:10.1080/13688804.2012.752963.

- Prescott, Andrew. “Searching for Dr. Johnson: The Digitization of the Burney Newspaper Collection.” In Travelling Chronicles: News and Newspapers from the Early Modern Period to the Eighteenth Century, edited by Siv Gøril Brandtzæg, Paul Goring, and Christine Watson, 51–71. Leiden: Brill, 2018. doi:10.1163/9789004362871.

- Reddy, William. The Navigation of Feeling: A Framework for the History of Emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Requate, Jörg. Journalismus als Beruf. Entstehung und Entwicklung der Journalistenberufs im 19. Jahrhundert Deutchland im Internationalen Vergleich. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1995.

- Requate, Jörg. “Kennzeichen des deutschen Mediengesellschaft des 19. Jahrhunderts.” In Das 19. Jahrhundert als Mediengesellschaft, edited by Jörg Requate, 30–42. Munich: R. Oldenbourg Verlag, 2009.

- Riecke, Jörg, and Britt-Maria Schuster. Deutschsprachige Zeitungen in Mittel- und Osteuropa. Sprachliche Gestalt, historische Einbettung und kulturelle Traditionen. Berlin: Weidler Buchverlag, 2005.

- Rintelen, Michael von. Zwischen Revolution und Restauration: Die Allgemeine Zeitung 1798–1823. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1992.

- Scheer, Monique. “Are Emotions a Kind of Practice (And is That What Makes Them Have History?): A Bourdieuian Approach to Understanding Emotion.” History and Theory 51 (2012): 193–220.

- Schönhagen, Philomen. Unparteilichkeit im Journalismus. Tradition einer Qualitätsnorm. Tübingen: Niemayer, 1998.

- Senneterre Renneville, Sophie de. Nina, oder: die gute Tochter. Haas: Wien, 1817. Accessed 4 January 2020 from ÖNB Sammlung von Handschriften und alten Drucken. http://data.onb.ac.at/rep/1037AE38.

- Seton, Rosemary. “Reconstructing the Museum of the London Missionary Society.” Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art and Belief 8, no. 1 (2012): 98–101. doi:10.2752/175183412X13286288798015.

- Stöber, Rudolf. Deutsche Pressegeschichte: Von den Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart. 3. überarbeitete Auflage. Köln: Herbert von Halem Verlag, 2014.

- Vierhaus, Rudolf. “Bildung.” In Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland, edited by Otto Brunner, Werner Conze, and Reinhart Koselleck, 508–551. Stuttgart: Ernst Klett Verlag, 1972.

- Vogel, Andreas. Die populäre Presse in Deutschland. Ihre Grundlage, Strukturen und Strategien. München: Verlag Reinhard Fischer, 1998.

- Wijfjes, Huub. “Digital Humanities and Media History. A Challenge for Historical Newspaper Research.” Journal for Media History 20, no. 1 (2017): 4–24. doi:10.18146/2213-7653.2017.277.

- Wilke, Jürgen. “Zensur und Pressefreiheit.” In Europäische Geschichte Online (EGO), edited by Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte (IEG), 2013. http://ieg-ego.eu/de/threads/europaeische-medien/zensur-und-pressefreiheit-in-europa.