Abstract

The scale of newspaper digitization and emergence of computational research methods has opened new opportunities for scholarship on the history of the press–as well as a new set of problems. Those problems compound for research that spans national as well as linguistic contexts. This article offers a novel methodological approach for confronting these challenges by synthesizing computational with conventional methods and working across a collaborative multilingual team. We present a case study studying the transnational and multilingual news event of Hungarian revolutionary Lajos Kossuth’s journey to the United States in 1851–52. Our approach helps to demonstrate some of the characteristic patterns and complexities in transatlantic news circulation, including the pathways, reach, temporality, vagaries, and silences of this system. These patterns, in turn, offer some insights into how we understand the significance of this era for histories of the press.

Introduction

While it is widely established that historical news circulated transnationally, there remain many obstacles to studying this phenomenon with digitized newspaper collections.Footnote1 The scale of newspaper digitization and emergence of computational research methods has opened new opportunities for scholarship on the history of the press–as well as a new set of problems. This article explains how those problems compound for research that spans national as well as linguistic contexts. Especially when conducted at scale, research on digitized newspapers can be severely limited by nationalized digitization histories, technical interoperability, and the language restrictions of collections as well as researchers. Our article confronts these challenges of digital newspaper research by synthesizing computational with conventional methods and working across a collaborative multilingual team. We present a case study warranting such an approach with Lajos Kossuth: specifically, his trip to the United States in 1851–52 to seek support for the Hungarian Revolution. This visit became a major transatlantic and multilingual news event.Footnote2 Our approach helps to document a fuller picture of such an event, demonstrating the notable processes and patterns by which newspapers constituted it transatlantically and across languages.

Digital Obstacles of Transnational Research

In 2013, historian Bob Nicholson assessed the changing landscape of digitized scholarly resources–and newspapers in particular–as heralding a ‘“digital turn” in humanities scholarship, driven by the creative use of online archives and a willingness to imagine new kinds of research.’Footnote3 He was among numerous commentators to express such hopes not only for digitized collections but innovative methods of researching them. At the same time, Nicholson (and others) have remained rightly critical of the problems inherent in digital newspaper collections, ranging from representativeness, OCR quality, access, varying metadata standards, and the distortions of scholarship largely shaped by available online collections, keyword search, and web-based interfaces.Footnote4 Nanna Bonde Thylstrup has deepened these critiques by identifying the complex political formations that sustain mass digitization projects, yet which often remain invisible as infrastructure or as assemblages of global factors far beyond an academic user’s usual purview.Footnote5 Thus, to ‘imagine new kinds of research’ with digital newspaper collections is not simply a matter of considering the digitized content nor its novel forms of access or computational manipulation, but requires confronting the political and institutional circumstances in which those collections and scholarly researchers find themselves.

Digitized historical newspapers especially bear those traces because of the histories of their digitization, often as part of national initiatives connected to libraries, museums, and cultural heritage institutions–themselves invested in projects of sovereignty.Footnote6 While seemingly motivated to make knowledge more accessible, these projects have ironically become restricted by the circumstances of their own production: each built with bespoke standards, interfaces, and encoded platforms that limit their interoperability.Footnote7 Furthermore, digital newspaper collections are typically defined within a certain language, or otherwise privilege keyword-based searching which does not find matches in translation. The politics and infrastructure of digital collections thus remediate the kinds of national, regional, and linguistic forces already at work in newspapers and their historiography.Footnote8 Heidi J. S. Tworek points out that ‘[e]very interaction with digital sources, then, interacts with a double politics: the politics of the sources themselves and the politics of their digitization.’Footnote9

As Lara Putnam has argued, the ability to search digitized resources seems to energize a broader transnational turn in historically-minded scholarship. And yet digital collections have sometimes limited or even distorted these pursuits, siloing materials and imposing systemic blind spots based on what is available.Footnote10 Maria DiCenzo suggests that digitization has neither fundamentally changed our concept of the periodical nor our methods for studying it, calling for a ‘methodological pluralism’ as a way forward.Footnote11 Relatedly, other critics have emphasized the need ‘to escape the confines both of national markets and monolingualism’–which are as much products of infrastructure as scholarly inclination.Footnote12 But while scholarship on press history recognizes the importance of international circulation, the pursuit of that scholarship runs up against institutionalized obstacles of how digitized research materials and even scholarly practice have been segregated, often by language. Methodological pluralism needs to be complimented by multilingualism.

In what follows, we share such an approach to research on digitized newspapers. This includes blending digital search and computational pattern discovery beyond the use of keyword searches, looking across historical newspaper collections and languages, and honoring the hard work of sustained international collaboration. To produce more nuanced scholarship on media and press histories, we must also commit to identifying and then navigating the national, institutional, and technological borders that too often keep our scholarly efforts separated. Our work emerges from a larger collaborative project called Oceanic Exchanges (OcEx) that uses such methods to track information flow across a broad, international corpus of newspapers in several languages, covering more than 100 million newspaper pages published between 1840–1914.Footnote13 Our case study focuses on an exemplary news event for transnational, multilingual study: the mid-century travels of the Hungarian revolutionary, Lajos Kossuth. After fleeing Hungary following the failed uprising in 1849, Kossuth toured internationally to drum up support for Hungarian independence, including a visit to the United States in 1851–52 that captured press attention worldwide. Reports about and reactions to this visit abounded within the international and multilingual landscape of nineteenth-century newspapers. Our mixed methods and multilingual approach to researching Kossuth helps to demonstrate some of the characteristic patterns and complexities in transatlantic news circulation. In the following section, we explain some key aspects of our data and methods before turning to the analysis of Kossuth as a news event.

Text Reuse Detection, Visualizations and Transnational Collaboration

Our sources span historical digitized newspaper collections from the United States, Britain, Germany, Austria, and Finland comprising thousands of articles published in multiple languages during the nineteenth century. These sources are by no means comprehensive: they represent a subset of the collections ingested by the OcEx project. Instead, they roughly track Kossuth’s own journey to the United States, helping to chart how politically controversial news traveled through different regions with varying levels of press freedom. As we focus on events during 1851–52, our study also considers paths and obstacles for transnational news circulation just before news agencies and submarine telegraph cables began reshaping news circulation in the second half of the nineteenth century.Footnote14 Knowing that Kossuth’s journey was an international phenomenon, we began this study less with a hypothesis than an interest in developing a methodology to explore that phenomenon across digital collections.

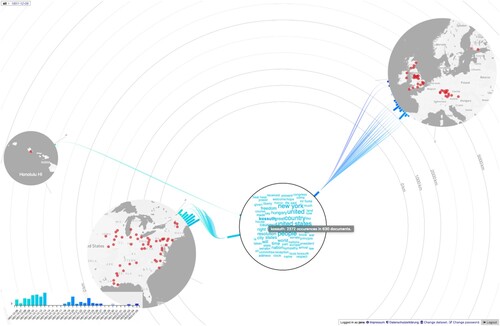

To find patterns across our data sets, we used software called passim to detect text reuse.Footnote15 But while passim works quite well for monolingual datasets, even those with messy OCR, no algorithm can currently detect textual reuse across different languages.Footnote16 We worked around this socio-technical challenge by synthesizing the project’s distant readings with our team’s own close analysis of multilingual news. Passim software provided us with ‘clusters’ of reprinted texts within our collections and timeframe; we supplemented this by creating our own smaller corpus of Kossuth news collected through keyword search in various languages. Each of these data sets included metadata about source newspapers, location, date, and article text. This allowed further exploration with Lilypads, which is an interactive visualization tool to analyze the textual, temporal, and geographical dissemination of articles (see ).Footnote17 With LilyPads, we were able to visualize and rearrange news articles according to date and place in order to see connections as well as unevenness in our dataset. Comparing the two datasets, combining close and distant reading approaches, and using text mining and information visualization techniques all allow us to study the event’s large-scale transatlantic representation as well as its granular coverage in different contexts.

FIGURE 1. The interface of LilyPads. This view shows the total temporal distribution and a word cloud of frequent words from the visualized documents, alongside the spatial distribution of the 668 articles published between December 6, 1851, and January 5, 1852. The majority of articles in this dataset were published in the United States.

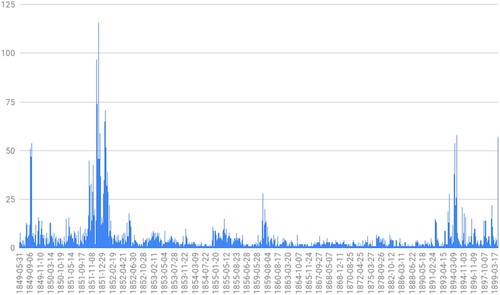

This approach revealed a massive amount of articles circulating around Kossuth’s American tour. Kossuth’s journey, arriving in New York in December 1851 and subsequently traveling to Washington, DC, prompted an explosion of coverage and reprinted texts, and signaled the highest level of reprint activity within our collections, including his mentions during the Hungarian revolution in 1848–1849 or the news of his death in 1894 (see ). These computationally-detected reprint clusters allowed us to consider chains of connections, including the approximate paths of the traveling news and the speed of flow. While we are interested in tracing a developing international press network, we also wanted to consider the disruptions and localized differences of how news variously manifested within it. The clusters tended to overrepresent English-language texts–likely caused by their prevalence in our source data, potentially also by differences in newspaper editing practices and how much text was copied verbatim by other papers.

FIGURE 2. The bar plot of the number of reprinted articles mentioning Kossuth in OcEx corpus shows that the American tour established Kossuth as an international celebrity.

To study more closely how news about Kossuth’s American tour crossed linguistic and political borders, we created a smaller, handpicked dataset by detecting the first appearance of this event in each newspaper repository and extracting all articles within seven days. Because in the early 1850s it could take weeks for a news story to travel long distances, the week for New York started on December 6th, in Vienna on December 21st, and for the Finnish newspapers on December 30th, 1851. This smaller collection (668 articles in total) let us read, compare, and discuss the reception of Kossuth as well as its changes across collections and languages.

The guiding questions of our analysis became: when and where does news about Kossuth’s arrival appear? What news propagated and why? What texts circulated not just about his arrival, but within the larger penumbra of this event? Can we find similar texts (reprints and translations) or anomalies in different languages? How, ultimately, might Kossuth’s case help illuminate the transnational patterns and problems of news circulation in the nineteenth century? In the following section, we share some of our findings about Kossuth’s American tour, reflect on which methodological steps lead to the individual findings, and speculate on their significance for histories of the press.

Patterns of Transnational News Circulation: Repetition, Alterations, and Silences

At a basic level, our findings confirm that Kossuth’s US tour and publicity campaign was indeed a major international news event. It illustrates patterns of transnational news before permanent oceanic telegraph cables, as well as how the press responded and was changed by the revolutionary movements of 1848.Footnote18 As the New York Herald declared, ‘The arrival of Kossuth on our shores will mark a political epoch’.Footnote19 In many ways it did: as Kossuth appealed to crowds, the press, and politicians to support Hungarian independence, he tapped into a mid-century zeitgeist, spurring debates in countries still reckoning with the consequences of the failed 1848 revolutions for themselves. Questions about national rights of self-determination were extremely delicate. Kossuth’s approach to the US government was watched closely for whether the US might take action in the international arena. The Senate had been debating whether to break diplomatic relations with the Austrian Empire, while many Americans, and particularly recent European immigrants having fled the suppression of the rebellions of 1848–49, were sympathetic to the Hungarian cause.Footnote20 At the same time, Kossuth was considered a dangerous rebel by Austria and Russia. Thus, the official US response to Kossuth’s visit was primed to be big news everywhere, with reaching diplomatic implications.

We found that almost every step of Kossuth’s US tour resounded through the internationalizing network of nineteenth-century newspapers. His various movements, engagements, and even physical condition were reported in detail, speeded along by a still-expanding information infrastructure of letters, telegraphs, railways, steamships, and press offices. His speeches were transcribed, translated, widely reprinted, published as books, and commented upon extensively in newspapers. His actions provoked published comment by editors, diplomats, and political operatives–often attempting to harness or distort Kossuth’s publicity for their own causes. In some cases, this turned into a disinformation campaign or even the outright censorship of any Kossuth news. His American tour thus offers a useful case study to help identify the complex patterns of news circulation at mid-century. Our research sought to illustrate the pathways, reach, temporality, vagaries, and silences of this system, at least as represented within our collections. These patterns, in turn, offer some insights into how we understand the significance of this era for histories of the press.

We offer the following observations from our case study, each explained in further detail below:

The transatlantic news network is patterned by its temporalities and path dependencies. These can each be exploited to different ends.

Reprinted news does not imply identical copies. Text often gets reframed, especially when translated across languages.

The system of news reprinting allows for a tactical supply of content to the press, sometimes aimed at manipulating public opinion or spreading disinformation.

The prevalence of reprints about a topic can also indicate censorship in places where they do not appear.

While Kossuth news was ‘international,’ a shared awareness of the topic breaks down into different, if not competing, views based on locality, language, and political context.

Some of these observations confirm what scholars already understand about the press. That understanding, in itself, may be usefully tested or affirmed with mixed digital methods and multilingual materials. But Kossuth’s case also usefully concentrates these observations into a sense of how the transatlantic press might work as a system. Though we can only begin to sketch that here, we hope that other scholars will build upon these methods and arguments in developing a more complex picture of nineteenth-century news circulation at scale and across languages.

Our computational detection and manual identification of reprinted news within our collections confirm the appeal of international news and its syncopated rhythm in the 1850s. As Rantanen explains, telegraphy ‘changed the temporality and sense of place on the news landscape, partly by making those into saleable features of news from far away.’Footnote21 Yet Kossuth appears within a news landscape not yet globally synchronized by intercontinental telegraph cables and international news agencies. Within domestic arenas connected by train and telegraph, news spread relatively quickly. Internationally, and particularly intercontinentally, it could take weeks for a specific news item to spread: the same text could be ‘the latest news’ in Washington, DC in December, and in February in Sydney. These time delays can imply a model of news diffusion based on distance, but reprint distribution and language comparison show more complicated patterns. For instance, some texts spread widely across continents while other texts, although widely copied within national borders, remained there. While Kossuth news spread almost everywhere, suggesting an internationally shared awareness of a topical news event, it also variously fell into news pockets. These are delineated by a combination of network infrastructure, language, political boundaries, and local interests, all of which affected how Kossuth’s trip was reported and interpreted.

While we endeavored to find all relevant news about Kossuth’s US visit within our collections, we were especially interested in what news propagated across the smaller corpus, whether by reprints, translation, adaptation, or otherwise.Footnote22 Reprinting reflects the perceived interest of news while it also amplifies that interest because of its wide circulation–a feedback loop that Ryan Cordell describes as virality.Footnote23 Texts that crossed the seas to be reprinted in other political and cultural contexts likewise appealed to readers across national, cultural and political boundaries. In general, Cordell suggests that certain newspaper content seem more conducive to newspaper reprinting and thus transmission: ‘the most viral media are interpretively flexible and highly adaptable rhetorically, aesthetically, politically, or otherwise.’Footnote24 Kossuth’s case exemplifies how this adaptability intersects with regional and international politics, as news of his trip followed the paths and pockets of a transatlantic network.

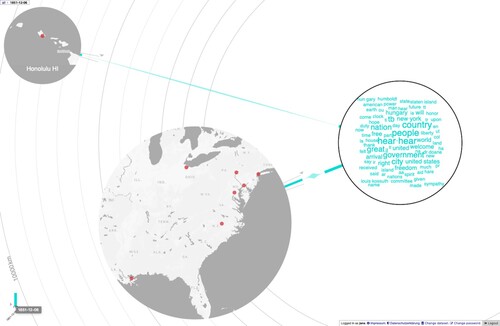

Reprints and translated versions let us trace reports of Kossuth’s trip and how they changed across contexts. The world was watching, and US newspapers supplied abundant details for readerships at home and abroad. It would be, according to the American Telegraph, ‘the greatest pageant ever witnessed since the days of Lafayette’.Footnote25 Comparing these first weeks of coverage suggests how Kossuth’s arrival was reported in different countries and how, collectively, they shaped the narrative about his potentially epochal visit. The news materially contributed to this pageantry, as most would only witness Kossuth’s visit through its reports. News publicity thus became part of the spectacle: the announcement of Kossuth’s arrival ‘spread through the country with lightning speed and is now doubtless known from Maine to the mouth of the Mississippi,’ as shows.Footnote26

FIGURE 3. This view of LilyPads shows the locations of articles about Kossuth (43) published in the United States on December 6, 1851. Close readings reveal that they range from former speeches he delivered in England, news about extensive preparations of his arrival, his appearances to the excitement of the members of the public.

We found that reprinted and translated news about his arrival was also a hot topic in Europe, though generally lacking the fulsome detail of US reports. One text in particular was widely shared among all European locations. This article reported that when Kossuth’s ship came up the bay, it was saluted by the discharge of thirty-one guns: one for each US state. In Europe, the news (from the New York Herald) started in London on December 18 (The Standard) where it within the UK and reached the German states on December 22 (Bayreuther Zeitung and Aschaffenburger Zeitung) where it was reprinted in several other German papers the following days, even once in Austria in the satirical paper Der Humorist, and finally on January 5, 1852, Grand Duchy of Finland of Russian Empire (Finlands Almänna Tidning, Helsinki). This widely reprinted article shows the fewest alterations as it circulated–yet even here, notable differences start to arise. While the American papers used phrases such as ‘the illustrious Hungarian liberator’ or ‘Governor Kossuth,’ the European papers simply called him Kossuth. Even reprints refracted the news as they traveled, differently shaping the political and public images of Kossuth that the press would construct.

We would, of course, expect such differences in the presentation of news in different papers and political contexts. We underscore those differences here as a corrective. As Huber and Osterhammel argue, ‘[g]lobal history’s tendency to emphasize connections at the expense of the ‘disconnected’ results in the triumphant pictures of worldwide interconnectedness.’Footnote27 We would add a similar caution about a bias for finding connectivity in computational studies. The automated detection of a ‘reprint,’ for instance, in no way indicates that a text was identically shared, much less how it may have been received. Computational discovery needs the counterbalance of close analysis to help identify the inflections of news in transmission. Similarities and anomalies within the news reprinting network mirror the foreign policy tensions between the Austrian Empire and Russia, on the one side, and the US, Great Britain and the German states on the other. US newspapers portrayed Kossuth as, in the words of the mayor of New York, ‘the eloquent advocate of universal freedom’ and widely reprinted Kossuth’s speeches as well as his positive reception by the American public.Footnote28 But European papers painted a different picture, emphasizing Kossuth’s physical ailments and strained family relations. Even though news traveled across the Atlantic within the first weeks of Kossuth’s arrival in the US, stories were reframed, reduced in terms of sensational and optimistic content, and even shaped by misinformation and conspicuous silences.

Counting the number of similar texts in our corpus is not enough to understand the manipulative diversity of editorial reprinting practices. Though European newspapers shared American news, they did so unevenly. Some noticed this one: ‘Kossuth arrived out on the 5th instant, was on the 6th at quarantine, till arrangements could be made to receive him. He was to make his public entry on the 6th. Great preparations had been made to receive him.'Footnote29 This timeline emphasized the preparations, but the European papers would make Kossuth’s ‘quarantine’ central to their messaging. On December 20, the Southampton Herald reprinted US news about Kossuth’s arrival, but they added that Kossuth ‘was to stay at Staten Island for a short time, until he had recovered [from] the fatigue of his voyage during which, we understand, he had suffered much ‘from sickness’.'Footnote30 This extra detail did not spread widely in Britain, but it certainly did in the German papers in Bavaria: starting on December 23 in the Bayreuther Zeitung, spreading to Regensburger ZeitungFootnote31 to Neue Passauer Zeitung (Passauer Zeitung).Footnote32

While text reuse helped us to identify and cluster similar texts from different collections, only a close analysis revealed how the insertion of a simple negation can manipulate the message. At the moment Kossuth made landfall, the US papers were already declaring that Kossuth was highly welcomed by European immigrants ‘in behalf of the adopted citizens of the United States’.Footnote33 However, as these reports traveled across Europe, they became more ambivalent. The Daily News (London) added to its reprint on December 18 that ‘[i]t is a singular fact, however, that the foreigners here, who affiliate as socialists and red republicans, have been unable to agree as to the propriety of welcoming him.'Footnote34 In its own version of the news, the German paper the Aschaffenburger Zeitung (December 24) claimed that American immigrants had agreed not to welcome him. The Allgemeine Zeitung shared the same content, citing The Globe (London), and underscoring how remarkable it was that other political refugees in America were turning their backs on Kossuth. Thus, as news of Kossuth’s reception spread across the Atlantic and into Europe, it mutated: sometimes reflecting the prejudices and preoccupations of its contexts, and sometimes having been intentionally distorted to serve a political agenda.

The agents of these changes can be difficult to identify, but in some cases, we find examples of how Kossuth and his critics each manipulated the system. As an experienced former editor,Footnote35 Kossuth knew how to use the newspaper to publicize his ideas and the Hungarian cause. For his part, Kossuth not only performed stirring speeches for crowds, he made sure to provide transcripts to the press to amplify his message.Footnote36 Reprints of those transcripts would carry the speech even further. Kossuth was also actively monitoring and responding to reports in the news.Footnote37 Kossuth’s Austrian opponents would also enter the fray by publishing their diplomatic correspondence in the international press. These included the publication of letters from Johann Georg Hülsemann,Footnote38 the Austrian Chargé d'Affaires in Washington, to the US Secretary of State Daniel Webster. As Kossuth and Hülsemann each understood, the route to diplomatic success wound through official channels as well as various gambits in the press. The Austrians had originally published Hülsemann’s letter in order to win public opinion in Austria and to undermine Kossuth’s mission in the US before he could arrive.Footnote39

Hülsemann’s letter also helps reveal the path dependencies of news in circulation.Footnote40 In the text, Hülsemann questioned the American government’s ability to represent liberty and equality considering the enslavement of African Americans and the genocide of indigenous peoples. The document concludes by claiming that the Emperor of Austria regards slavery as disgraceful and fully expects a ‘Black Kossuth’ to rise in the US. While this may sound like an endorsement of radicalism, the Austrians knew that linking Kossuth to abolition would irreparably split the American Congress. And it did. Even without Austrian prompting, American abolitionists were quick to see common cause with the ‘great liberator.’ For instance, the letter appeared in the Anti-Slavery Bugle (New-Lisbon, Ohio) where it was introduced under the title of ‘The emperor of Austria rebuking Slavery.’ This affiliation was enough for white Southern politicians to dismiss Kossuth out of hand. The Congressional acts of Kossuth’s reception became tinged by the internecine debate over slavery. Kossuth presented Americans with a question of foreign affairs, but the rhetorical adaptability of his case–an appeal for freedom–saw it shifted into different localized contexts, making it even more attractive for newspapers to circulate. In fact, when reprints of Hülsemann’s letter appeared in Britain, they had acquired this American dimension of the debate. Circulation could follow circuitous routes. Even as the same text was reprinted in several newspapers in several places, it accrued different meanings and conveyed them according to the news network’s uneven topologies.

Comparing sources across collections allows us to identify other forms of misinformation, fake news, and censorship active within this transatlantic news framework. For example, Kossuth’s family would get dragged into the fray. Kossuth left them behind when he went into exile; their fate was spun quite differently depending on where news about them appeared. On December 18, the Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh) was the first to report that Kossuth’s relatives had been arrested; his mother was put under surveillance in their home.Footnote41 On December 20, other UK papers relayed from ‘a credible source’ that a train full of prisoners–including Kossuth’s sisters and mother–had arrived in Vienna.Footnote42 Yet the Dublin-based Freeman’s Journal noticed that the German-language papers ‘are completely silent on the subject.'Footnote43 The Northern Star (Leeds) linked this silence to government censorship about Kossuth’s mission.Footnote44

German-language papers did publish news that might injure Kossuth emotionally or damage his reputation: for instance, that his poor suffering mother died in his absence. This news was completely fake. While scholarship on fake news mainly looks to the 20th and 21st centuries, scholars such as Heidi Tworek clarify that ‘fake news’ has a longer history as information warfare during political contests.Footnote45 On December 23, the Fürther Tagblatt, Fürth published a notice of her death. This was echoed on the same day by the Würzburger Stadt- und Landbote (Würzburg) citing ‘a credible source’ which turned out to be the constitutional newspaper from Bohemia (dated December 17, 1851), having published a death notice from Pest.Footnote46 This seemingly credible news was reprinted throughout the following days in several German-language newspapers, spreading especially quickly in the military district Pesth and Ofen, one of the administrative units of the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary, and even including details about the exact hour of her death and subsequent funeral. Even The Standard (London) was drawn in (December 25). The source of this misinformation is not clear. It was not long before pro-Kossuth papers uncovered the ruse. On December 26, the Bayreuther Zeitung (Bavaria) exposed the fabrication. But the correction of a rumor is far less newsy than the rumor itself and did not spread as widely.

Comparing different collections also allows us to investigate gaps: both in digitization as well as historic press coverage. The absence of news–especially where we would expect to find it, given the virality of Kossuth news–can be an equally significant marker of political interference. Consider the case of Finland.Footnote47 We found news and reprints about Kossuth in the Swedish-language newspapers in Finland, aimed primarily at the Swedish-speaking elite of the country. However, nothing about Kossuth appears in the Finnish-language newspapers that were primarily read by people in lower social classes. The reason was censorship, imposed by Russian authorities of the Grand Duchy of Finland. From 1850–60, the Finnish language press could not publish any news on political events abroad.Footnote48 The ruling elites of Europe feared another round of the 1848 revolutions, and they considered the growing press as a potential source of moral and social threats. Materials targeted more to the lower classes were in general more strongly censored than news addressed to the elites and the educated.Footnote49

Ultimately, Kossuth did not attain the commitments he had hoped for. The fireworks of Kossuth’s arrival in New York fizzled with his eventual disappointments in Washington, DC, where US officials tried to appear welcoming without signaling any policy commitment.Footnote50 That avoidance, in itself, was a resounding decision in the international sphere. It galvanized each piece of news about Kossuth’s reception in DC, circulating quickly and widely in the European newspapers.Footnote51 In response, Kossuth published an announcement that he considered his mission in the US failed, citing the opposition of US officials.Footnote52 Kossuth was likely deploying the same tactic he had used in Great Britain where he was similarly rebuffed: he publicized his disappointment with government officials in hopes of generating moral and material support from the public.Footnote53 But although Kossuth’s declaration of failure targeted the American public, it too went internationally viral, resonating differently in various political spheres. Reprints of Kossuth’s address to President Fillmore, the President’s response, and Kossuth’s reaction show this dynamic at work internationally.Footnote54 The Washington DC based Daily Union introduced the texts by complaining that the President was acting contrary to public opinion of Kossuth.Footnote55 The Times in London republished the same text on Kossuth’s and Fillmore’s meeting, but framed it instead with Kossuth’s comments that his mission had failed.Footnote56 Such published addenda, in turn, allowed other newspapers simply to reprint the report that Kossuth’s mission had failed, without including the speeches or additional context at all.

The framings of these reprints reveal how the news network simultaneously created a globally hot topic, which all the newspapers wanted to address, yet one that fractures into perspectives suitable for newspapers’ cultural and political contexts and worldview. We found that although the same texts were reprinted widely, creating a kind of common exposure to important events and texts, this did not reflect a common understanding of those events or their meaning, even within a given language.Footnote57 News was simultaneously international and domesticated. The global circulation of texts created a common awareness of significant issues, but what they signified for readers changed as reprints moved through different contexts, were manipulated, or even suppressed. Kossuth himself tailored his messages to make Hungarian independence a ‘culmination point’ for contemporary debates.Footnote58 Similarly, news about Kossuth was rhetorically adapted everywhere, driving its broad circulation and usefulness for newspapers and political operatives as they catered to readers and wrestled for public opinion. Thus, while Kossuth’s trip to the US was a non-event relative to the epochal political shifts that some commentators had forecast, it has more significance as a news event, resounding throughout our collections and suggesting some of the powerful workings of a transatlantic news network at mid-century.

Coda

Computational techniques can help identify the extent of such a news event, as in tracking reprints, but we should be careful not to mistake textual similarities as evidence for shared understanding. Transnational history has been energized by the relative availability of digitized resources and tools to discover connections across them. Digital newspaper collections and computational methods certainly afford new ways of looking at transnational press systems, but with caveats. Not only is the digitized corpus incomplete, but the internationalizing press system is just as patterned by local contexts, political wrangling, and censorship as much as it represents a network of connected information. Likewise, digital collections and computational methods each do not sufficiently address the challenges of news in multiple languages. We hope to have suggested how digital methods can be augmented with careful, collaborative, and multilingual studies to better understand the connectedness and contingencies of the historical press.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Jamie Parker for his valuable contributions at the early phases of this study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jana Keck

Jana Keck, German Historical Institute, Washington, District of Columbia 20009, United States of America. E-mail: [email protected]

Mila Oiva

Mila Oiva, Tallinn University, Tallinn 10120, Estonia. correspondence E-mail: [email protected]

Paul Fyfe

Paul Fyfe, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina 27695, United States of America. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1 Östling et al., Circulation of Knowledge; Raymond and Moxon, “News Networks”.

2 For definitions and studies of ‘news events’, see Dayan & Katz, Media Events; Ytreberg, “Towards Historical Understanding”; Schlott, “Papal Requiems”.

3 Nicholson, “The Digital Turn”.

4 Ibid.; Gooding; Milligan; Jarlbrink and Snickars, “Cultural Heritage as Digital Noise”; Hakkarainen, “The Cultivation of Emotions”.

5 Thylstrup, Politics of Mass Digitization.

6 Ibid., 21.

7 Beals and Bell, Atlas of Digitised Newspapers.

8 Raymond and Moxam, “News Networks,” 4.

9 Tworek, “Digital History and Global Publics,” 335.

10 Putnam, “The Transnational and the Text-Searchable.”

11 DiCenzo, “Remediating the Past,” 20.

12 Chapman, “Transnational Connections,” 184.

13 For other examples of OcEx research, see Cordell, “Reprinting, Circulation”; Smith, Cordell and Mullen “Computational Methods”; Vesanto et al. “A System for Identifying”; Oiva et al. “Spreading News”.

14 For studies of news networks in the wake of these changes, see Rantanen, “The Globalization of Electronic News in the 19th Century”; Müller, Wiring the World; Wenzlhuemer, Connecting the Nineteenth-Century World.

15 Smith, “Passim program”.

16 Several scholars have effectively used reprint detection on monolingual newspaper collections at scale, including Cordell, Beals, and Vesanto et al. But automating translation to detect reprints in different languages has so far proved too difficult.

17 Franke et al. “LilyPads”.

18 Bösch, Mediengeschichte, 89, 105.

19 The New York Herald, December 7, 1851.

20 Nyirady, “Libel of Not?”, 3–4; Smith, The Presidencies, 230–232.

21 Rantanen, “The Globalization of Electronic News in the 19th Century,” 615.

22 For related studies of news reprinting, see Smits “Looking for The Illustrated London News,” 85; Cordell, “Viral Textuality”; Beals, “Scissors and Paste”; Pigeon, “Steal it, Change it, Print it.”

23 Cordell, “Reprinting”, 418, 424.

24 Cordell, “Viral Textuality”, 35.

25 The American Telegraph, December 6, 1851.

26 The Republic, December 6, 1851.

27 Huber and Osterhammel, Global Publics, 32.

28 This address is widely reprinted in the US, but only twice in Europe: in London in the Morning Chronicle (December 22, 1851) and in the Manchester Times (December 24, 1851.).

29 Reprinted in Daily News, Morning Chronicle (December 18, 1851), Essex Standard (December 19, 1851), Examiner, Northern Star, Sheffield Independent (December 20, 1851), Allgemeine Zeitung, Aschaffenburger Zeitung (December 23, 1851).

30 The Southampton Herald, December 20, 1851.

31 December 24, 1851.

32 Ibid.

33 See, for instance, American Telegraph, December 6, 1851.

34 This story is reprinted in Sheffield Independent (December 20, 1851), Caledonian Mercury (December 22, 1851), and Dundee Courier (December 24, 1851).

35 Nyirady, “Libel or Not?,” 2.

36 See Kossuth’s speech in New York, New York Daily Tribune, December 8, 1851.

37 Nyirady, “Libel or Not?,” 5; See Kossuth’s corrections, for example, in clusters No 369368706902, No 1271311707957, and No 103080363485, circulating between December 9 and 29, 1851, with altogether 61 reprints.

38 Smith, The Presidencies, 231; United States Department of State. Foreign Relations, 190–191; Buchanan The Works, 174.

39 See Huelsemann and Webster, The Austro-Hungarian Question; Nyirady, “Libel or Not?,” 4; Smith, The Presidencies, 231.

40 Wenzlhuemer, Connecting the Nineteenth-Century World, discusses path dependence in relation to news technologies. See also David, “Path Dependence”.

41 As its source, the article refers to a letter from Pest (Hungary), dated December 1, 1851, which was published in the Journal of Frankfort; reprinted in the Royal Cornwall Gazette, Essex Standard, December 19, 1851, Huddersfield Chronicle and Lancaster Gazetteer, December 20, 1851. US papers like, for instance, the Wilmington Journal, reprinted it on January 9, 1852.

42 The Daily News mentioned as its source the Kreuz-Zeitung (Berlin).

43 The Freemans Journal, December 24, 1851.

44 The Northern Star, December 20, 1851.

45 Tworek, News from Germany.

46 Reprinted also in Bavaria in the Regensburger Tagblatt, Bayerische Landbötin, Bayerisches Volksblatt, Regensburger Morgenblatt, Allgemeine Zeitung, Neue Speyerer Zeitung, and Münchener Tagblatt, December 24, 1851; Baierscher Eilbote, December 25, 1851.

47 For a detailed case study, see Rantala and Hakkarainen, “The Travelling of News in 1848.”

48 Neuvonen, Sananvapauden, 113–117.

49 Goldstein, The War for the Public Mind, 5, 9; Lenman, “Germany”, 38, 49–50.

50 Smith, The Presidencies, 232.

51 Circulating predominantly between January 1 and February 1, 1852, altogether 151 reprints.

52 Circulating predominantly between January 6 and 25, 1852, altogether 56 copies.

53 Lada, “The Invention”, 7, 13.

54 Reprinted predominantly between January 1 and 28, 1852, altogether 56 times in the US and UK.

55 The Daily Union, January 1, 1852.

56 The Times, January 20, 1852.

57 For a study of how Civil War-era readers saw similar content in dramatically different political contexts, see Cordell “Reprinting.”

58 Lada, “The Invention”; Roberts, “Lajos Kossuth”.

Bibliography

Digital Newspaper Collections

- Austrian National Library Virtual Newspaper Reading Room ANNO

- Bavarian State Library

- British Newspaper Archive

- Cengage Newsvault

- Chronicling America Historic American Newspapers

- Europeana Newspapers

- Hemeroteca Nacional Digital de México

- National Library of Australia digital newspaper collection Trove

- National Library of Finland digital newspaper collection

- National Library of the Netherlands

- National Library of Wales

- New Zealand’s PapersPast

Literature

- Beals, M.H. “Scissors and Paste: The Georgian Reprints, 1800–1837.” Journal of Open Humanities Data 3, (2017): 1–5. doi:10.5334/johd.8.

- Beals, Melodee, and Emily Bell. “The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata: Reports from Oceanic Exchanges,” January 28, 2020. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11560059.v1, 2020.

- Bösch, Frank. Mediengeschichte: Vom Asiatischen Buchdruck zum Fernsehen. Frankfurt am Main: Campus-Verl, 2011.

- Buchanan, James. The Works of James Buchanan, Comprising His Speeches, State Papers, and Private Correspondence. Volume 7. Philadelphia & London: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1909.

- Chapman, Jane. “Transnational Connections.” In The Routledge Handbook to Nineteenth-Century British Periodicals and Newspapers, edited by Alexis Easley, Andrew King, and John S Morton, 175–184. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Cordell, Ryan. “Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network Author in Antebellum Newspapers.” American Literary History 27, no. 3 (2015): 417–445. doi:10.1093/alh/ajv028.

- Cordell, Ryan. “Viral Textuality in Nineteenth-Century US Newspaper Exchanges.” In Virtual Victorians: Networks, Connections, Technologies, edited by Veronica Alfano, and Andrew M Stauffer, 29–56. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- David, Paul. “Path Dependence: A Foundational Concept for Historical Social Science.” Cliometrica: The Journal of Historical Economics and Econometric History 1, no. 2 (2007): 91–114.

- Dayan, Daniel, and Elihu Katz. Media Events: The Live Broadcasting of History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

- DiCenzo, Maria. “Remediating the Past: Doing ‘Periodical Studies’ in the Digital Era.” English Studies in Canada 41, no. 1 (2015): 19–39.

- Franke, Max, Markus John, Moritz Knabben, Jana Keck, Tanja Blascheck, and Steffen Koch. “LilyPads: Exploring the Spatiotemporal Dissemination of Historical Newspaper Articles.” Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Information Visualization Theory and Applications. Valletta, Malta (2020).

- Goldstein, Robert Justin. The War for the Public Mind: Political Censorship in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 2000.

- Gooding, Paul. Historic Newspapers in the Digital Age: Search All About It!. London: Routledge, 2016. doi:10.4324/9781315586830

- Hakkarainen, Heidi. “The Cultivation of Emotions in the Press.” Media History (2021): 1–17. doi:10.1080/13688804.2021.2013182.

- Huber, Valeska, and Jürgen Osterhammel. Global Publics: Their Power and Their Limits, 1870-1990. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Huelsemann, Johann Georg, and Daniel Webster. The Austro-Hungarian Question. Correspondence Between Mr. Huelsemann and Mr. Webster. Washington: Gideon & Co, 1851.

- Jarlbrink, Johan, and Pelle Snickars. “Cultural Heritage as Digital Noise: Nineteenth Century Newspapers in the Digital Archive.” Journal of Documentation 73, no. 6 (October 4, 2017): 1228–1243. doi:10.1108/JD-09-2016-0106.

- Lada, Zsuzsanna. “The Invention of a Hero: Lajos Kossuth in England (1851).” European History Quarterly 43, no. 1 (2013): 5–26. doi:10.1177/0265691412468309.

- Lenman, Robin. “Germany.” In The War for the Public Mind: Political Censorship in Nineteenth-Century Europe, edited by Goldstein Robert Justin, 35–80. Westport: Praeger, 2000.

- Milligan, Ian. “Illusionary Order: Online Databases, Optical Character Recognition, and Canadian History, 1997–2010.” The Canadian Historical Review 94, no. 4 (2013): 540–569.

- Müller, Simone M. Wiring the World: The Social and Cultural Creation of Global Telegraph Networks. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

- Neuvonen, Riku. Sananvapauden historia Suomessa [The History of the Freedom of Speech in Finland]. Tallinna: Gaudeamus, 2018.

- Nicholson, Bob. “The Digital Turn.” Media History 19, no. 1 (2013): 59–73. doi:10.1080/13688804.2012.752963.

- Nyirady, Kenneth. “Libel or Not? The War of Words Between Lajos Kossuth and New York Editor James Watson Webb.” Hungarian Cultural Studies 11 (2018): 1–10. doi:10.5195/ahea.2018.317.

- Oceanic Exchanges Project website. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://oceanicexchanges.org/.

- Oiva, Mila, Asko Nivala, Hannu Salmi, Otto Latva, Marja Jalava, Jana Keck, Laura Martínez Domínguez, and James Parker. “Spreading News in 1904. The Media Coverage of Nikolay Bobrikov’s Shooting.” Media History 25, no. 3 (2019): 1–17. doi:10.1080/13688804.2019.1652090.

- Östling, Johan, Erling Sandmo, David Larsson Heidenblad, Anna Nilsson Hammar, and Kari H. Nordberg. In Circulation of Knowledge: Explorations in the History of Knowledge. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 2018.

- Pigeon, Stephan. “Steal It, Change It, Print It: Transatlantic Scissors-and-Paste Journalism in the Ladies’ Treasury, 1857–1895.” Journal of Victorian Culture 22, no. 1 (2017): 24–39. doi:10.1080/13555502.2016.1249393.

- Putnam, Lara. “The Transnational and the Text-Searchable: Digitized Sources and the Shadows They Cast.” American Historical Review 121, no. 2 (2016): 377–402.

- Rantala, Heli, and Heidi Hakkarainen. “The Travelling of News in 1848: The February Revolution, European News Flows, and the Finnish Press.” Journal of European Periodical Studies 7, no. 1 (2022): 13–28. doi:10.21825/jeps.81955.

- Rantanen, Terhi. “The Globalization of Electronic News in the 19th Century.” Media, Culture & Society 19, no. 4 (1997): 605–620.

- Raymond, Joad, and Noah Moxham. “Chapter 1: News Networks in Early Modern Europe.” In News Networks in Early Modern Europe, edited by Joad Raymond, and Noah Moxham, 1–16. London: Brill, 2016. doi:10.1163/9789004277199.

- Roberts, Tim. “Lajos Kossuth and the Permeable American Orient of the Mid-Nineteenth Century.” Diplomatic History 39, no. 5 (2015): 793–818. doi:10.1093/dh/dhu070.

- Schlott, René. “Papal Requiems as Political Events Since the End of the Papal State.” European Review of History: Revue Européenne D’histoire 15, no. 6 (2008): 603–614. doi:10.1080/13507480802500210.

- Smith, David, Ryan Cordell, and Abby Mullen. “Computational Methods for Uncovering Reprinted Texts in Antebellum Newspapers.” American Literary History 27, no. 3 (2015): E1–E15. doi:10.1093/alh/ajv029.

- Smith, David. “Passim program.” 2012-2017. Last visited February 8, 2021. https://github.com/dasmiq/passim.

- Smith, Elbert B. The Presidencies of Zachary Taylor & Millard Fillmore. Lawrence, Kan: University Press of Kansas, 1988. http://archive.org/details/isbn_9780700603626

- Smits, Thomas. “Looking for The Illustrated London News in Australian Digital Newspapers.” Media History 23, no. 1 (2017): 80–99. doi:10.1080/13688804.2016.1196585.

- Spencer, Donald, Louis Kossuth, and Young America. A Study of Sectionalism and Foreign Policy, 1848-1852. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1977.

- Thylstrup, Nanna Bonde. The Politics of Mass Digitization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018.

- Tworek, Heidi J. S. News from Germany: The Competition to Control World Communications, 1900–1945. News from Germany. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2019. doi:10.4159/9780674240728.

- Tworek, Heidi J.S. “Digital History and Global Publics.” In Global Publics: Their Powers and Limits, 1870–1990, edited by Valeska Huber, and Jürgen Osterhammel, 313–342. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- United States Department of State. Foreign Relations of the United States. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1965.

- Vesanto, Aleksi, Asko Nivala, Tapio Salakoski, Hannu Salmi, and Filip Ginter. “A System for Identifying and Exploring Text Repetition in Large Historical Document Corpora.” In Linköping Electronic Conference Proceedings, 330–333. Linköping: Linköping University Electronic Press, Linköpings universitet, 2017.

- Viral Texts Project Website. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://viraltexts.org/.

- Wenzlhuemer, Roland. Connecting the Nineteenth-Century World: The Telegraph and Globalization. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Ytreberg, Espen. “Towards a Historical Understanding of the Media Event.” Media, Culture & Society 39, no. 3 (2017): 309–324.