Abstract

During the nineteenth century, suicide rates rose substantially in many countries, including the geographic region of the present state of Austria. Sensational news reporting about suicides may have contributed to this rise by eliciting so-called copycat suicides, a phenomenon termed the ‘Werther effect.’ We conducted a large-scale content analysis of nineteenth-century suicide reporting (N = 14,638) to provide a descriptive account of the quality of suicide reporting back then. We found that much of the sensational reporting of the nineteenth century was characterized by presenting vivid details on the suicide method, specific location, and personal details, such as the deceased’s name, occupation, and exact address. To put these findings into context, we compared them to twenty-first-century suicide reporting (N = 300 articles). We found that the quality of reporting has improved since then, containing less Werther-effect-facilitative elements, however, the reports still fail to adhere to modern-day guidelines of responsible reporting.

Introduction

Many European countries experienced a rise in suicide rates during the nineteenth century, resulting in suicide becoming a mass phenomenon.Footnote1 In the geographical region of the present state of Austria, suicide rates drastically rose within a period of two decades, roughly between 1860 and 1880.Footnote2 This rise is assumed to be related to the societal-level processes of modernization, such as industrialization, urbanization, secularization, and the decrease in social integration due to the weakening of the bond between the individual and society, which is considered a major risk factor for suicide.Footnote3 Apart from modernization, it has been hypothesized that the press was another possible contributing factor.Footnote4 Modern-day empirical evidence suggests that irresponsible sensational reporting on suicides can elicit imitative effects and thus lead to an increase in copycat suicides. This phenomenon has been termed the Werther effect.Footnote5

As a systematic longitudinal assessment of historical suicide reporting is still pending, this lack of knowledge of the quality of suicide reporting during the nineteenth century served as the starting point of the present research. We have conducted a content analysis of nineteenth-century suicide reporting in Austria and compared it to modern-day reporting, aiming to provide a descriptive account of how the press reported on suicides in the past. Thus, this study sets out to provide a detailed description of suicide reporting in the nineteenth century and outline its similarities to and differences from present-day suicide reporting.

Reporting on Suicide

Reporting on suicides does not necessarily elicit detrimental effects.Footnote6 However, several elements of suicide reporting have been identified as facilitating imitative effects. (1) Giving undue prominence to a suicide article is one of the elements associated with a subsequent rise in suicides.Footnote7 (2) Including location-related information can create so-called suicide hotspots (e.g. bridges, cliffs, railway tracks).Footnote8 (3) Including information on the suicide method, which can easily be replicated, and details on the exact manner of death, such as the lethal dosage of the drug taken, increases the risk of copycat suicides.Footnote9 (4) Including information about the deceased that could increase identification, such as the person’s gender, age, name, or occupation, has also been shown to increase the strength of the Werther effect.Footnote10 (5) Reporting on a celebrity suicide increases the risk of suicide among the general population by 13% which is likely due to public’s strong identification with celebrities (vertical identification) and high prominence of news stories.Footnote11 Horizontal identification (e.g. the same age or gender) further augments this effect.Footnote12

Including the elements mentioned above in suicide reports would nowadays be considered sensational reporting, considering the possible detrimental effects of such news reports. Yet, back in the nineteenth century, there were no guidelines for responsible reporting on suicides in place. There are multiple factors leading to a high level of—what we would today consider—sensationalism in the nineteenth-century suicide reporting, particularly in the second half of the century. First, the (late) nineteenth century press generally tended to rely on a rather sensational and dramatic style of writing,Footnote13 including in news topics, such as crime, celebrity news, and suicide reporting. In the second half of the nineteenth century, so-called Kreuzerblätter (analogous to the penny press in the USA) increased in popularity, which relied on sensational news to achieve large distribution numbers to make up for the cheap cost. Second, several innovations in the Austrian media landscape took place in the nineteenth century,Footnote14 leading to the rise of local papers and the emerging mass press. Local papers, such as the Morgen-Post (1854; one of the first successful local papers), were published focusing on provincial affairs, which meant more coverage of local suicide news and more vivid details as well. Two decades later, the Illustrirte Wiener Extrablatt was first published, representing the emerging mass press, which focused on exciting, amusing, and shocking news, including pictures on its front pages. Third, as mentioned earlier, suicide rates rose during the nineteenth century, with an especially steep rise between 1860 and 1880,Footnote15 which provided newspapers with more suicide-related events to report on. Finally, the resultant increased coverage of suicide-related materials led to interpellations made by politicians in the parliament with regard to suicides,Footnote16 which could in turn have elicited heightened salience and prominence of suicides in the news.

Several studies provide preliminary empirical evidence for sensational suicide reporting in the nineteenth century and at the beginning of the twentieth century. For example, Wasserman, Stack, and ReevesFootnote17 found that The New York Times displayed a considerable number of front-page suicide articles in 1913 and 1914: this hyper-coverage was not attributed to a rise in suicides in the area; rather, it was due to the editor who at the time acted as a ‘moral entrepreneur.’ Similarly, ArendtFootnote18 content analyzed suicide reporting in two Austrian newspapers in 1855, 1865, 1875, and 1885 and found a significant quantity of sensational suicide reporting. RichardsonFootnote19 analyzed suicide reporting in two Canadian newspapers in 1844–1990 and found that the newspapers frequently included suicide reports, which were treated as everyday occurrences. The author also found that those articles included details on the exact manner of death (e.g. ‘swallowing 55 grains of opium’Footnote20) and reported about everyday people as everyday occurrences.

Notably, Richardson mentioned that suicide reports included the deceased’s full names and further identifying characteristics, Footnote21 which not only had detrimental consequences for the deceased’s families within society (suicide was considered ungodly and shameful) but also showed that people’s rights and privacy were not taken into account. For example, according to Article 10 of the Basic Law on the General Rights of Nationals,Footnote22 quoting, or reprinting suicide letters violated the secrecy of correspondence in Austria, and publishing defamatory statements of one’s private and family life that did not concern public interest became punishable in 1849.Footnote23 The law specifically mentioned that it applied to the living as well as the deceased.Footnote24

Moreover, although suicide is a complex, multidimensional phenomenon,Footnote25 both Richardson and ArendtFootnote26 mentioned that suicide was often attributed to a single cause, such as financial hardship, lovesickness, or chronic illness. Such monocausal explanations oversimplify the issue and can lead the public to believe that suicide is inevitable if one presents with a problem, such as stated above. This perception can prevent vulnerable individuals from seeking help and others from providing help to such individuals. Repeated exposure to such oversimplistic, monocausal explanations for suicide can consolidate these effects.

The insights of Richardson and ArendtFootnote27 served as a valuable starting point for this project as the authors’ aim to present a historical exploration of suicide reporting aligns with ours. However, their studies used very small samples, which did not allow for generalizable claims. The present project sets out to assess suicide reporting in a more systematic way, involving a large sample that encompasses multiple newspapers over almost an entire century. Thus, leaning on the existing empirical findings and the discussed reasons as to why sensational reporting could have risen in the second half of the nineteenth century, we hypothesized that sensational suicide reporting was prevalent in the nineteenth century, rising in popularity during the second half of the century (Hypothesis 1, H1).

Importantly, responsible reporting on suicides can mitigate copycat behavior. For instance, reporting about an individual who has successfully overcome their suicidal crisis and found an alternative way to cope with their suicidal thoughts (i.e. a positive role model) can be considered suicide-preventive. In fact, such stories related to hope and recovery are associated with a reduction of suicide rates, a phenomenon termed ‘Papageno effect.’Footnote28

Knowledge of the Werther effect and suicide-preventative media effects had not been available until recently. In Austria, the first guidelines on responsible reporting were introduced in 1987, amid a surge of subway suicides.Footnote29 A subsequent decrease in subway suicides by 75% was attributed to the implementation of journalistic guidelines. Currently, several national and international organizations have issued media guidelines to aid journalists in navigating this sensitive topic.Footnote30 These guidelines urge media professionals to omit Werther-effect-facilitating content elements, stressing the fact that suicide is preventable and making help more accessible, for instance, by providing the public with information on where to seek help (e.g. telephone counseling services). Due to the increased scientific knowledge of imitation effects and suicide prevention, as well as a greater salience of the topic among journalists, we argue that when comparing the nineteenth-century suicide reporting with the twenty-first-century suicide reporting, the current reporting has improved, becoming less sensational from a suicide prevention standpoint (Hypothesis 2, H2).

Method

The present study is part of a larger research project on suicide reporting in the nineteenth century, starting from 1819, when suicide statistics became available. We conducted a large-scale content analysis of suicide reporting, focusing on the content elements of suicide reporting mentioned above. The present paper presents a descriptive analysis of individual elements of suicide reporting without focusing on the study of possible detrimental Werther effects. A comparison with today's reporting allows for a more thorough understanding of the reporting style back then as it puts the historical findings into context.

Sample

In this research, we relied on the newspapers available in the Austrian National Library’s online archive (Austrian Newspaper Online, ANNO) and selected 20 newspapers that met the following requirements: (1) They were written in German, (2) published in the geographic region of the present state of Austria, representing different territories of the monarchy, (3) had a high circulation, and (4) represented different newspaper types. Melischek and Seethaler’s review of the Austrian pressFootnote31 during that time guided our selection.

Coders

We recruited 17 coders who were able to read Frakturschrift, the German typeface used in nineteenth-century newspapers. The participants were screened for increased levels of hopelessness based on the Hopelessness Scale by Beck and SteerFootnote32 prior to coder training. They underwent rigorous training to ensure high-quality standards and to learn about Werther effects, which allowed us to guard against any changes in their mental health during and after the coding process (see Ethics Statement).

Procedure

We performed four rounds of pretesting until all variables of interest’s Krippendorff’s Alphas indicated high intercoder reliability. All possible newspaper-year combinations (e.g. Neue Freie Presse, 1872) were randomly assigned to the coders, who used the given newspaper and year as a filter in the ANNO database search using the search term ‘Selbstmord’. As stated earlier, evidence suggests that the term ‘Selbstmord,’ which translates literally as ‘self-murder,’ is problematicFootnote33 and shall therefore not be used. However, this knowledge was not available to journalists in the nineteenth century. Thus, this term was the most common description for suicide.Footnote34 Utilizing a standardized randomization process, n = 30 newspaper articles were coded for each newspaper—year combination, where possible. Only one newspaper was available throughout the entire observation period: all other newspapers were only available for a limited time, some papers disappeared, then reappeared, and some were simply not available in the ANNO database. For some years, our search did not yield any codable suicide reports at all (i.e. 1826, 1827, 1829, 1831, and 1844). Therefore, our sample consisted of N = 14,638 articles published in the nineteenth century. In addition, to ensure high data quality and assess the coders’ reliability during the actual coding process, all coders independently analyzed three newspaper—year combinations, unaware that they were coded by everyone.

Comparison with the Twenty-first Century

To put the findings into context and test H2, we also content-analyzed a small sample consisting of three years of suicide articles in contemporary news reporting. Relying on the Austrian Press Agency’s online database, we searched for suicide articles within 10 newspapers with the highest distribution available online. Because the term ‘Selbstmord’ is not the only term used in suicide reporting nowadays, we added keywords to our search that paraphrase ‘suicide’, such as ‘Suizid,’ ‘Freitod,’ and ‘Selbsttötung.’ None of these terms was frequently used in the nineteenth century. We sampled n = 10 suicide articles per year per newspaper, resulting in a total of 300 articles for our comparison.

Measures

Sensational reporting was measured by assessing several elements of suicide reporting that we outlined above. In particular, we assessed whether the article appeared on the front page, used a suicide reference in the headline, and was accompanied by an illustration, or a picture. We noted whether it mentioned or cited a suicide note, analyzed the amount of suicide method- and location-related information, identified which personal details of the deceased were mentioned (e.g. their name, gender, age, occupation, and social status) and whether there was any speculation about the cause of the suicide. Lastly, we assessed whether the article mentioned that suicides are preventable, whether the report featured a positive role model who had overcome a suicidal crisis and whether the article offered any help for vulnerable individuals. A detailed list of all variables and their measurement and the respective Krippendorff’s Alphas (intercoder reliability test results) can be found in the Supplemental Online Material.

Ethics Statement

The project was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Department of Communication, University of COVERED FOR REVIEW (Number ID: 20210414_026, dated May 3, 2021). Due to the sensitivity of the topic, supervision measures included mental health check-ins and continuous monitoring before, during, and after the coding process.

Results

We hypothesized that sensational suicide reporting was prevalent in the nineteenth century, rising in the second half of the nineteenth century (H1). To test this, we assessed the change in the prevalence of each element over time. We divided the nineteenth century into four time segments: Period I, the time before the March Revolution 1848 (1819–1847); Period II, the time after the Revolution but before the sharp increase in suicide rates (1848–1859); Period III, the time of the rapid increase in suicides (1860–1880); and Period IV, the time after the increase in suicides (1881–1899).

Evidence of Sensational Reporting in the Nineteenth Century

presents the findings related to all coded variables and formal statistical tests.

TABLE 1. Change in use of content elements during the nineteenth century

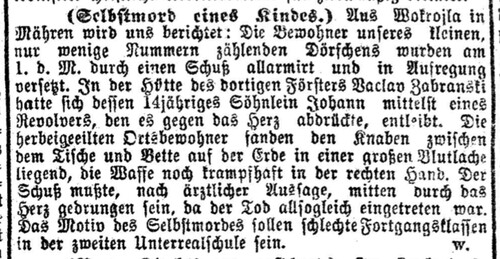

We found that the use of most elements of sensational news reporting significantly increased over time. Regarding prominence, we found that most suicide stories could be found on the inside of the paper, frequently presented in the local news or Vermischte Nachrichten [mixed news] section, between the news of severe weather, social events, or celebrity news. In most cases, these reports consisted of merely a few lines but were packed with details on the suicide. None of the reports in our sample included an illustration or picture. Thus, at first glance, the stories did not seem to receive much prominence; however, the use of the German word ‘Selbstmord’ [self-murder] or a similar reference to suicide in an article’s headline increased from 5.5% in Period I to 21.8% in Period II, and then drastically surged (60.8%) between 1860 and 1880, rising to 74.5% in Period IV (see ). Furthermore, in the second half of the century, approximately one in 10 reports included a quote from the deceased’s suicide note. Many suicides were depicted in a very vivid way, illustrating the scene in a graphic manner, as can be seen in an example in .

Figure 1 (Source: Morgen-Post, August 5, 1870, p. 3). English Translation: (Self-murder of a child.) We are told from Mokrojla in Moravia: The inhabitants of our small village, encompassing only a few numbers, were alarmed and stirred by a shot on the first of the month. In the hut of the local woodsman Vaclav Zabranski, his 14-year-old son Johann took his life using a revolver, which he shot pressing against his heart. The townspeople hurried to the hut and found the boy lying between the table and the bed on the floor, in a large pool of blood, the weapon still convulsive in his right hand. The shot must have, according to the doctor’s statement, gone straight through the heart for the death occurred immediately. The motive for this self-murder is likely to be bad grades in the second year of middle school.

The location of the suicide was reported in most articles (69.7% in Period I, rising to 84.5% in Period IV). Most nineteenth-century suicide reports (from 66.1% in Period I to 82.1% in Period IV) mentioned specific locations (a place that could be identified and found by a third person), such as a city, street, or bridge. Few reports used vague descriptions of the location, such as ‘in the woods.’ Many of the suicide articles reported on the deceased’s place of living; some of these articles even included the exact mailing address. For example, the newspaper Neue Freie Presse wrote: ‘The 54-year-old carter Franz Götz, residing in Neu Lerchenfeld, Kirchenstraße No. 31, hung himself ere-yesterday afternoon in his bedroom using a vine-cord from the window.’Footnote35 Taking a closer look at the development of this element’s use over time, we found that its use increased after 1868 and peaked in 1896, when 25.5% of all suicide news reports contained the deceased’s full address.

The suicide method was reported in 42.2% of the articles in Period I, in 78.5% in Period II, 85% in Period III, and culminating in 84.3% in the last period under investigation. In Periods II, III, and IV, most reports provided additional details on the suicide method, such as the exact height from which the person jumped, which body part was shot, or the specific drug used.

Despite the brevity of the articles, nineteenth-century suicide reports included a lot of personal details. The inclusion of identification-evoking elements (e.g. the deceased’s name, gender, age, or occupation) intensified around 1860, indicated by a rise in means (see ). Reporting on the deceased’s social status (e.g. celebrity, or aristocrat) did not increase over time. In fact, the nineteenth-century press mostly reported on common people rather than aristocrats or celebrities.

In sum, the press reported on suicides in a sensational way, and there appeared to be an increase of sensationalism, as indicated by an increased use of suicide referents in the headlines, mentioning of the suicide method, a specific address, and the deceased’s personal details, such as their name, gender, age, occupation, or place of living. Therefore, evidence supports H1.

Comparison with Modern-day Suicide Reporting

We hypothesized that contemporary suicide reporting is less sensational compared to that of the nineteenth century (H2). depicts our nineteenth-century findings compared to the twenty-first century, along with results of the formal statistical tests conducted.

TABLE 2. Testing differences between nineteenth-century and twenty-first-century suicide reporting

We found that modern-day suicide reports use a suicide referent considerably less frequently (18.5%) than in the nineteenth century (64.3%). Interestingly, the location of the suicide is still mentioned in most reports (63.7%), although less often (compared to 84.0% in the nineteenth century). Furthermore, the suicide method is still discussed in 35.3% of modern-day suicide reports, and 23% of reports provide details on the method.

In the nineteenth century, the name of the person who died by suicide was mentioned in 67.3% of the reports. Notably, 46.9% contained the full name of the deceased, 8.8% used their first name only, and 11.5% stated only their last name. Contemporary suicide reports still often include the full name of the deceased (31% of the cases), which is likely attributed to an increase in reports about celebrity suicides and a decrease in reports about common people. The deceased’s gender was included in 95.4% of the nineteenth-century articles and 84.7% of the modern-day articles. While suicides are more common among men, we found that male suicides were overrepresented in both the nineteenth century (78.4% men, 16.9% women) and modern-day reporting (68% men, 16.7% women). The deceased’s age was stated in 36.5% of the nineteenth-century reports but in 56% of the modern-day reports. Interestingly, the deceased’s occupation was predominantly reported (70.3%) in the nineteenth century, whereas only 33.7% of articles report on the individual’s profession now. Celebrity suicide reports comprise 5.3% of the nineteenth-century sample and 15% of the modern-day sample. Note that social status was often equated with aristocracy in the nineteenth century, thus, we coded any mention of aristocratic belonging as a celebrity suicide report. Despite that, the low number of celebrity suicides in the nineteenth century supports Richardson’s claim that the press used to mostly report suicides among the common public.Footnote36

The nineteenth-century findings indicate that it was common to identify one single reason that (must have) caused the suicide. About half of the reports in our sample (47.5%) stated one specific cause for the suicide, such as ‘aus Liebeskummer’ (‘out of love-sickness’), only 5.2% of reports mentioned that the suicide could be attributed to multiple risk factors. Frequently, journalists who were not able to report a single cause wrote that the cause was unknown, nevertheless implicating that there must have been a single reason that had caused the event. Interestingly, there is no significant difference between nineteenth-century and modern-day reporting when it comes to monocausal explanations (see ).

It came as no surprise that little attention was paid to possible suicide-preventative elements of reporting in the nineteenth century: suicides were hardly ever presented as avoidable (0.3%). In the few cases that we did find, reports did not imply that suicides were unnecessary deaths, Footnote37 but rather in the sense that suicides had to be avoided because it was not acceptable to die by suicide. Harsh judgments of suicidal individuals were common as people who died by suicide were presented as weak.Footnote38 However, our sample included an advertisement that pointed to a new healing method for ‘melancholy, thoughtfulness, nonsense, deliriousness and suicide’.Footnote39 Other than that, not a single article in our historical sample offered help to vulnerable readers, for instance, by providing information on self-help groups or organizations. Currently, 14.7% of the articles reporting suicide contain a reference to a helpline or similar sources. Only eight suicide articles in our entire historical sample of more than 14,000 suicide reports depicted stories of people who had overcome a suicidal crisis and found a different solution (i.e. positive role model), for instance, a news story in the Grazer Zeitung titled Zur Verhütung der Selbstmorde.Footnote40 In our modern-day sample, only 3% of articles featured a positive role model. While this presents a significant increase compared to the nineteenth century, the strength of the increase in this possibly Papageno effect evoking content element is not as big as the decrease in possibly Werther effect evoking elements.

To summarize, we found significantly less sensationalism in the twenty-first-century suicide reporting, as indicated by a smaller prevalence of using suicide referents in headlines, mentioning suicide notes, locations, or method details. Moreover, modern-day reports included significantly fewer personal details of the deceased; only the age of the deceased is stated more often now than it used to be in the nineteenth century. Twenty-first-century reporting uses significantly more elements that can elicit suicide-preventative effects. A striking finding was that there was no significant difference between nineteenth-century and modern-day reporting concerning monocausal explanations. Overall, the findings largely support H2.

Discussion

This study draws from an extensive dataset assessing more than 14,000 suicide reports covering almost an entire century. The large volume of articles under investigation adds substance to previous findings and enriches our understanding of how the press portrayed suicides in the nineteenth century. Analysis of this extensive data collection showed that nineteenth-century suicide reports used a sensational narration style, vividly depicting method- and location-related details and providing a great amount of personal information on the deceased. The press often infringed the deceased’s personal rights by quoting suicide notes and depicting details of the suicide or the deceased themselves. Journalists often included a speculative cause for the suicide, which could be problematic as the readers could perceive suicide to be the norm in such situations and, in case they found themselves in a similar life crisis, use it as a decision-making shortcut instead of seeking help or confiding in their friends and family.

Importantly, as described above, sensational elements of suicide reporting, such as giving undue prominence, disclosing the exact location, depicting the method, and providing personal details of the deceased, have been shown to be contributing factors to the imitative Werther effect. Our findings indicate that the use of elements associated with the Werther effect has decreased substantially in the twenty-first century compared to the nineteenth century, suggesting that contemporary reporting has become more responsible. However, a striking finding was that both then and now, monocausal explanations were frequently presented, despite the fact that suicide is a complex phenomenon and monocausal explanations may encourage vulnerable individuals to believe that suicide is inevitable, which may obstruct seeking and providing help.

Contemporary suicide prevention literature suggests that the use of elements facilitating the Papageno effect can evoke a suicide-preventing effect. Our analysis of nineteenth-century suicide reporting found only a negligible number of instances of journalists making use of such suicide-preventive elements. Although there is a statistically significant improvement with regard to the elements facilitating the Papageno effect since the nineteenth century, the improvement is not substantial: in the modern-day sample, only one in 10 articles referred to a suicide prevention hotline or stated that suicides were preventable, and only 3% of the articles included a role model, i.e. the story of a person who had overcome their suicidal crisis and found another way to cope with it. This observation indicates that the improvement of the Werther-effect elements (discouraging imitation) tends to be much stronger than the improvement of the Papageno-effect elements (encouraging alternative to suicide solutions). The articles in the modern-day sample did not fully adhere to the current media guidelines on responsible reporting, which suggests that there is still room for improvement.

Importantly, we want to stress the fact, that we are not to pass (contemporary) judgement upon journalists and newsrooms back in the nineteenth century. As mentioned earlier, research on Werther- or Papageno effects was not around back then. Furthermore, psychiatry had a different understanding of suicidality and mental health issues in the nineteenth century,Footnote41 which carried a multitude of religious stigmas.Footnote42 Thus, our modern-day suicide norms, morals, and attitudes simply do not reflect nineteenth-century reality. While some news reports look rather sensational to us now, journalists back then might simply have tried to report comprehensively and in great detail.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we relied on historical newspapers that were available in the ANNO database. While we are most grateful, that we were able to use the text-identification software allowing for keyword searches, there are some issues that came with its use (e.g. misidentification and illegibility). Second, by relying on the keyword search, it is possible that we missed suicide articles because journalists used different words to refer to the death. Third, despite the overall positive intercoder reliability results during the coder training pretests, we obtained a comparably low yet acceptable Krippendorff’s Alpha value for our location variables during the actual coding process (see Supplemental Online Material). Fourth, the interpretation of our data collected across the first half of the nineteenth century is limited, as we found only a small number of codable suicide articles. However, we found that there was a strong mid-century increase in the quantity of suicide reporting and analyzed more than 300 articles printed each year after 1867. This was the reason why we included more years in the first period (Period I) ensuring a solid database, even for the first half of the nineteenth century.

Conclusion

Despite its limitations, the present study’s extensive dataset presents supporting evidence for an increase in sensational suicide reporting during the nineteenth century. Comparing this nineteenth-century data with contemporary suicide reporting showed that although suicide reporting has become significantly more responsible, it still falls short of the standards prescribed by the contemporary media guidelines to ensure ethical coverage of sensitive news.

Supplemental_Online_Material.doc

Download MS Word (21.5 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Manina Mestas

Manina Mestas (author to whom correspondence should be addressed), Department of Communication, University of Vienna, Währinger Straße 29, 1090 Vienna, Austria. E-mail: [email protected]

Florian Arendt

Florian Arendt, Department of Communication, University of Vienna, Währinger Straße 29, 1090 Vienna, Austria. E-mail: [email protected]

Notes

1 Durkheim, Der Selbstmord; Ortmayr, “Selbstmord in Österreich”.

2 Kuttelwascher, “Selbstmord und Selbstmordstatistik”.

3 Stack, “Suicide in Finland”.

4 Arendt, “Reporting on Suicide”.

5 Phillips, “The Influence of Suggestion”.

6 (Citation covered for review).

7 See note 5 above.

8 Pirkis et al., “Interventions”.

9 Yip et al., “Celebrity Suicide”; Chan et al., “Charcoal-burning”.

10 Phillips and Carstensen, “Clustering of teenage suicides”.

11 Niederkrotenthaler et al., “Media and Suicide”.

12 Stack, “Celebrities and suicide”.

13 Sachsman and Bulla, Sensationalism.

14 Melischek and Seethaler, “Presse und Modernisierung”.

15 See note 2 above.

16 Leidinger, Die Bedeutung der Selbstauslöschung.

17 Wasserman, Stack and Reeves, “Suicide and the Media”.

18 Arendt, “Assessing Responsible Reporting”.

19 Richardson, “A History of Suicide Reporting”.

20 Ibid., 429.

21 Ibid., 429 and 433.

22 Staatsgrundgesetz über die allgemeinen Rechte der Staatsbürger (StGG), Dec. 21, 1867; cf. Olechowski, Die Entwicklung des Preßrechts.

23 § 32 Preßgesetz [Press Law], Mar. 13, 1849

24 § 34 Preßgesetz [Press Law], Mar. 13, 1849, cf. Olechowski, Die Entwicklung des Preßrechts.

25 Wasserman, Suicide: An Unnecessary Death.

26 See notes 18 and 19 above.

27 Ibid.

28 Niederkrotenthaler et al., “Werther v. Papageno Effects”

29 Etzersdorfer and Sonneck, “The Viennese Experience”.

30 E.g., Kriseninterventionszentrum Wien, Leitfaden; World Health Organization, Preventing Suicide.

31 See note 14 above.

32 Beck and Steer, Hopelessness Scale.

33 Arendt, “Framing Suicide”.

34 Acknowledging that the use of this word is not ideal, we believe that the translation ‘suicide’ in this paper would not do the actual word used justice, downplaying its effect on nineteenth-century readers.

35 Neue Freie Presse, March 15, 1879, 6.

36 See note 19 above.

37 See note 25 above.

38 Linzer Volksblatt, October 31, 1893, 5.

39 Linzer Tages-Post, March 12, 1890, 6.

40 Grazer Zeitung, December 30, 1865, 2–3.

41 Gnoth, Glaesmer, and Steinberg, “Suizidalität”.

42 Potter, “Is Suicide the Unforgivable Sin?”.

Bibliography

- Arendt, Florian. “Assessing Responsible Reporting on Suicide in the Nineteenth Century: Evidence for a High Quantity of Low-Quality News.” Death Studies 45, no. 4 (2021): 305–312. doi:10.1080/07481187.2019.1626952.

- Arendt, Florian. “Framing Suicide: Investigating the News Media and Public's Use of the Problematic Suicide Referents Freitod and Selbstmord in German-Speaking Countries.” Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 39, no. 1 (2018): 70–73. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000467.

- Arendt, Florian. “Reporting on Suicide Between 1819 and 1944: Suicide Rates, the Press, and Possible Long-Term Werther Effects in Austria.” Crisis: The Journal of Crisis Intervention and Suicide Prevention 39, no. 5 (2018): 344–352. doi:10.1027/02275910/a000507.

- Beck, Aaron T, and Robert A Steer. Manual for the Beck Hopelessness Scale. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation, 1988.

- Chan, Kathy P. M., Paul S. F. Yip, Jade Au, and Dominic T. S. Lee. “Charcoal-burning Suicide in Post-Transition Hong Kong.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 186, no. 1 (2005): 67–73. doi:10.1192/bjp.186.1.67.

- Durkheim, Emile. Der Selbstmord. Berlin, Germany: Suhrkamp, 1897.

- Etzersdorfer, Elmar, and Gernot Sonneck. “Preventing Suicide by Influencing Mass-Media Reporting. The Viennese Experience 1980–1996.” Archives of Suicide Research 4, no. 1 (1998): 67–74. doi:10.1080/13811119808258290.

- Gnoth, Mark, Heide Glaesmer, and Holger Steinberg. “Suizidalität in der Deutsch-Sprachigen Schulpsychiatrie.” Nervenarzt 89 (2018): 828–836. doi:10.1007/s00115-017-0425-9.

- Kriseninterventionszentrum Wien. “Leitfaden zur Berichterstattung über Suizid.” Accessed May 12, 2022 https://www.suizidforschung.at/suizidberichterstattung/.

- Kuttelwascher, Hans. “Selbstmord und Selbstmordstatistik in Österreich.” Statistische Monatsschrift 38 (1912): 267–351.

- Leidinger, H. Die Bedeutung der Selbstauslöschung: Aspekte der Suizidproblematik in Österreich von der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts bis zur Zweiten Republik. Vienna, Austria: Studien Verlag, 2012.

- “Melancholie, Tiefsinn, Blödsinn, Wahnsinn und Selbstmord infolge nervöser Zerrüttung!” [Melancholy, Thoughtfulness, Nonsense, Deliriousness, and Self-Murder Due to Nervous Breakdowns!] Linzer Tages-Post, March 12, 1890, 6.

- Melischek, Gabriele, and Josef Seethaler. “Presse und Modernisierung in der Habsburgermonarchie.” Chap., In Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918. Bd. VIII/2: Politische Öffentlichkeit und Zivilgesellschaft – Die Presse als Faktor der politischen Mobilisierung, edited by H. Rumpler, and P. Urbanitsch, 1535–1714. Vienna, Austria: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2006.

- Niederkrotenthaler, Thomas, Marlies Braun, Jane Pirkis, Benedikt Till, Steven Stack, Mark Sinyor, Ulrich S. Tran, et al. “Association Between Suicide Reporting in the Media and Suicide: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” BMJ 368 (2020): m575. doi:10.1136/bmj.m575.

- Niederkrotenthaler, Thomas, Martin Voracek, Arno Herberth, Benedikt Till, Markus Strauss, Elmar Etzersdorfer, Brigitte Eisenwort, and Gernot Sonneck. “Role of Media Reports in Completed and Prevented Suicide: Werther v. Papageno Effects.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 197, no. 3 (2010): 234–243. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.074633.

- Olechowski, Thomas. Die Entwicklung des Preßrechts in Österreich bis 1918. Vienna, Austria: Manzsche Verlags- und Universitätsbuchhandlung, 2004.

- Ortmayr, Norbert. “Selbstmord in Österreich 1819–1988.” Zeitgeschichte 17, no. 5 (1990): 209–225.

- Phillips, David P, and Lundie L Carstensen. “Clustering of Teenage Suicides After Television News Stories About Suicide.” New England Journal of Medicine 315, no. 11 (1986): 685–689. doi:10.1056/NEJM198609113151106.

- Phillips, David P. “The Influence of Suggestion on Suicide: Substantive and Theoretical Implications of the Werther Effect.” American Sociological Review 39, no. 3 (1974): 340–354. doi:10.2307/2094294.

- Pirkis, Jane, Lay San Too, Matthew J. Spittal, Karolina Krysinska, Jo Robinson, and Yee Tak Derek Cheung. “Interventions to Reduce Suicides at Suicide Hotspots: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet Psychiatry 2, no. 11 (2015): 994–1001. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00266-7.

- Potter, John. “Is Suicide the Unforgivable Sin? Understanding Suicide, Stigma, and Salvation Through Two Christian Perspectives.” Religions 12, no. 11 (2021): 987. doi:10.3390/rel12110987.

- Richardson, Gemma. “A History of Suicide Reporting in Canadian Newspapers, 1844-1990.” Canadian Journal of Communication 40, no. 3 (2015): 425–445. doi:10.22230/cjc.2015v40n3a2902.

- Sachsman, David B., and David W. Bulla. Sensationalism. Murder, Mayhem, Mudslinging, Scandals, and Disasters in 19th Century Reporting. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2015.

- “Selbstmord, Religion und Wissenschaft.” [Self-Murder, Religion and Science.] Linzer Volksblatt, October 31, 1893, 5.

- “Selbstmorde.” [Self-murders.] Neue Freie Presse, March 15, 1879, 6.

- Stack, Steven. “Celebrities and Suicide: A Taxonomy and Analysis, 1948-1983.” American Sociological Review 52, no. 3 (1987): 401–412. doi:10.2307/2095359.

- Stack, Steven. “The Effect of Modernization on Suicide in Finland: 1800–1984.” Sociological Perspectives 36, no. 2 (1993): 137–148. doi:10.2307/1389426.

- Wasserman, Danuta. Suicide: An Unnecessary Death. London: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Wasserman, Ira M., Steven Stack, and Jimmie L. Reeves. “Suicide and the Media: The New York Times's Presentation of Front-Page Suicide Stories Between 1910 and 1920.” Journal of Communication 44, no. 2 (1994): 64–83. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1994.tb00677.x.

- World Health Organization. “Preventing Suicide: A Resource for Filmmakers and Others Working on Stage and Screen.” Accessed May 11, 2022, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/preventing-suicide-a-resource-for-filmmakers-and-others-working-on-stage-and-screen.

- Yip, Paul S. F., K. W. Fu, Kris C. T. Yang, Brian Y. T. Ip, Cecilia L. W. Chan, Eric Y. H. Chen, Dominic T. S. Lee, Frances Y. W. Law, and Keith Hawton. “The Effects of a Celebrity Suicide on Suicide Rates in Hong Kong.” Journal of Affective Disorders 93, no. 1 (2006): 245–252. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.015.

- “Zur Verhütung der Selbstmorde.” [About prevention of self-murders.]. Grazer Zeitung, December 30, 1865, 2–3.