Abstract

This research investigates the discourse of the so-called ‘Spanish flu’ in the national Soviet newspapers Pravda (Truth) and Izvestia (News) during the epidemic period of 1918–1919. Our analysis revealed that discourse developed in three stages, each with specific characteristics. The nature of discourse was, above all, impacted by ideological factors, while reporters and Bolshevik authorities promoting this type of discourse were primarily guided by political expediency. Lack of adequate and comprehensive information on the disease, its etiology, and its spread not only around the world but also in Soviet Russia, administrative and bureaucratic problems, and simultaneous epidemics of other infectious diseases (cholera and typhus) were also significant factors.

Introduction

The pandemic of the so-called ‘Spanish flu’ (1918–1919) is considered to be one of the most widespread and devastating pandemics in the history of humankind.Footnote1 Despite being overlooked in academia for an extended period, the topic of the Spanish flu has seen a revival over the past few decades, with interdisciplinary research shedding light on complex implications.Footnote2 Historians have identified a ‘second wave’ of historiographyFootnote3 that adopts a multifaceted approach and delves into its broad epidemiological, social, and political ramifications. As the centenary approached, scholars urged new interpretative frameworks to re-evaluate the pandemic, partly motivated by analogies with contemporary influenza epidemics and the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote4 However, research on the Spanish flu in Russia is hindered by substantial obstacles, including a lack of data and concrete evidence regarding the epidemic's progression and impact.

Throughout the Spanish flu, humanity went through a period of tectonic shocks related to World War I, the fall of empires, and the foundation of new states. After October 1917, the former Russian Empire experienced global social and political upheavals accompanied by the chaos of civil war, foreign intervention, economic collapse, hunger, and struggle with internal opposition. Studies on the Spanish flu's intersection with these events demonstrate how it was often overshadowed by other significant historical developments, leading to its marginalization in collective memory.Footnote5 However, the actual explanation of this phenomenon may be complex and multifaceted. In Russia, there is a definite lack of severe artifacts related to the ‘Spanish disease’Footnote6 as no meaningful corpus of photographs, memoirs, and literature sources exists.

Why did the Spanish flu become an inconspicuous epidemic in Russia? We endeavored to partially address this question through the analysis of publications from the national Soviet press of the period, namely the newspapers Pravda and ‘Izvestia (News) of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets of Workers, Farmers, Cossacks and Red Army Deputies’ (further referred to as Izvestia). This examination employed a specific research design rooted in Discourse-Historical Analysis (DHA).Footnote7 The chosen newspapers were the primary mouthpieces of nascent Soviet power and had a major impact on citizens residing in Soviet Russia.Footnote8

The ‘Spanish flu’ in Russia and the World

Contemporary analyses have estimated the global mortality of the Spanish flu to be between 50 and 100 million deaths.Footnote9 Early assessments show an infection rate of 500 million individuals growing to potentially over a billion individuals worldwide, exceeding half of the contemporaneous global population.Footnote10. In the case of Soviet Russia, researchers have calculated the pandemic mortality at approximately 450,000, or 2.4/1,000 populationFootnote11—a rate much lower than that in many other countries. However, this scholarly estimate contrasts sharply with the higher fatality figures posited in popular histories, with L. SpinneyFootnote12 and J. BarryFootnote13 speculating as many as 2.7 and 10 million deaths in Russia, respectively.

The origins of the pandemic are the subject of an ongoing academic debate, with various locales such as military camps in Étaples, France, and Aldershot, the United Kingdom (UK), the Midwest of the USA, particularly Kansas, and regions in China being proposed as potential ground zeros.Footnote14 The researchers distinguished three major waves of the pandemic: spring–summer in 1918, autumn–winter in 1918, and winter–spring in 1919.Footnote15

The first wave of the Spanish flu mostly spared RussiaFootnote16 as by the spring of 1918, the disease had spread to Europe due to army movements, and one of the first political decisions of the Bolsheviks was to withdraw from the war. Consequently, Russian troops were not present on European battlegrounds. The Spanish flu that spread in the country in the autumn of 1918 was connected with a foreign military intervention.Footnote17 These circumstances helped Russia avoid the first epidemic wave; however, it experienced the second and third waves.

Simultaneously, in 1918–1919 in addition to the Spanish flu, Russia was fighting epidemics of other infectious diseases, such as cholera and typhus.

Media Response to the Pandemic

The first publication covering a new unknown illness was published on May 22, 1918, in the Madrid newspaper ABC,Footnote18 which is also the reason for the term ‘Spanish flu.’ The researchers explained that such information was published in Spain through existing military censorship in warring countries, while the Spanish Kingdom was not involved in the war; thus, their reporters and publishers had greater freedom of speech.Footnote19.

Stringent censorship in Germany led to the suppression of infection statistics and the downplaying of the seriousness of the epidemic.Footnote20 In the UK, the press paid minimal attention to the pandemic, as it was overshadowed by the Great War. Coverage that did occur urged the public to ‘carry on’.Footnote21. In the United States, the press provided exhaustive accounts of influenza, earning it the classification of a ‘mass-mediated disease’.Footnote22. However, the focus was predominantly on scientific and governmental narratives, often at the expense of personal stories, eclipsed by the broader narrative that endorsed wartime stoicism.Footnote23

The response of Russian media remains an under-researched area, and this study aims to address this research gap in academic literature.

Research Design and Method

The objectives of our study necessitated an analysis that encompassed not only the discourse related to the Spanish flu but also other contemporaneous medical discourses, combined with consideration of the performance of the healthcare system and the dynamics of various infectious diseases.

The research period was restricted by the time frame of the Spanish flu epidemic, which spread from July 1918 to March 1919. Within the first stage, we analyzed all the issues of the daily newspapers Pravda and Izvestia in order to define the agenda promoted at that time by the national Soviet press; subsequently, from the corpus of materials, we selected and studied all the publications mentioning the Spanish flu (also known as ‘Spanish disease’ and ispanka by the Soviet press) (N-103) as well as those referring to other epidemics spreading at that period (240). Moreover, the analysis would have been incomplete without understanding the overall medical discourse during the spread of the pandemic. Consequently, the corpus of texts included publications describing the Bolshevik government's actions in the healthcare system (110).

Content and thematic analysisFootnote24 of the publications related to the three major epidemics of that time, namely the Spanish flu, cholera, and typhus, allowed us to determine and compare the significance of the given diseases in the context of the media agenda of the period under consideration.

Subsequently, we performed a qualitative analysis of this corpus to unearth the underlying discursive strategies and connotations pertaining to the Spanish flu. To achieve these goals, we employed DHA, one of the Critical Discourse AnalysisFootnote25 methods, which integrates sociolinguistic studies within historical contexts and intertextual connections. This approach considers the interrelatedness of texts, genres, and discourse alongside sociological factors and situation-specific frames, thereby, highlighting the evolution of discourse in relation to socio-political transformation.Footnote26 The DHA framework underlines the critical importance of grasping and reconstructing the historical backdrop of discourse, enabling a diachronic examination that extends beyond mere static representation. This method applies several analytical devices, such as fields of action, genres, discourse topics, and five discursive strategies (i.e. nomination, predication, argumentation, perspectivization, and intensification/mitigation) and is particularly attentive to how language helps forge power dynamics and identities.Footnote27

To accomplish the objectives of our study and broaden the research scope, we consulted memoirs, subsequent publications by medical staff, and government acts pertaining to the healthcare system.

Newspapers Pravda and Izvestia in the Soviet Press System in 1918–1919

Over the period researched, the newspapers Pravda and Izvestia were the leading voices of the Bolsheviks’ power. The first issue of Pravda was published on May 5, 1912, the birthday of Karl Marx; however, the newspaper became an official mouthpiece of the Central Committee of the Russian social democratic labor party (of Bolsheviks) only after the October Revolution of 1917. The first issue of Izvestia was published on March 13, 1917, and on November 9 of the same year, it became an official edition of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of Workers, Farmers, Cossacks and Red Army Deputies. In this way, these two major newspapers of Bolshevik power somehow shared their responsibilities: Pravda was to cover the ruling party life, whereas Izvestia focused on the activities of state bodies and also published official decisions and decrees of the Soviet power. In 1918, Izvestia boasted the largest circulation among all the other Soviet press, 500,000 copies, while Pravda’s circulation was almost three times less.Footnote28

‘The Disease Caused by the Imperialistic War’

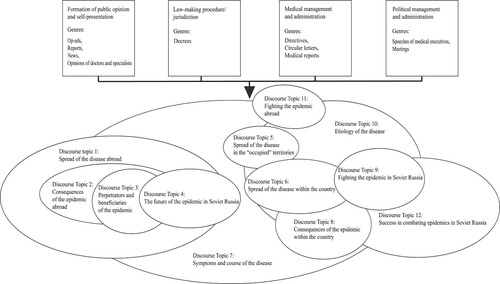

Twelve discourse topics were identified in the coverage of the Spanish flu epidemic by the Soviet press. These topics were associated with four principal Fields of Action: law-making procedures, formation of public opinion, medical management and administration, and political management and administration. illustrates the progression of these discourse topics, from the initial ‘Spread of the disease abroad’ to ‘Success in combating epidemics in Soviet Russia.’

The first news on ‘Spanish disease’ was published in Izvestia on July 14, 1918, that is, two months after the initial reports by the Spanish press. A small article in the column ‘Life abroad’ mentioned that the disease was spreading throughout Europe; however, the primary focus was on enlisting various regions of the UK and Germany, also providing a brief description of the Spanish flu’s devastating effect on different aspects of life there. One social actor, that is, ‘people’ constituting the European population suffering from hunger caused by the war and the object, that is, ‘the Spanish flu,’ which inflicted significant damage on Western economies, meet here.

Several days later, on June 16, 1918, Izvestia published a large article under the headline ‘Spanish disease’ by a deputy editor Platon Kerzhentsev (Lebedev). He interpreted this ‘new and unheard-of disease’ as a ‘symbol of disasters drawn upon the world as a result of predatory imperialism ruling’ (Izvestia, July 16, 1918). Western capitalist governments are blamed for the ‘Spanish flu’ emergence:

Capitalism civilization has come to a disreputable collapse! It ran against a bloody war and killed inhumanly millions of lives. It destroyed billions-worth of values created by many generations. It threw all the countries of the world into a state of hunger and poverty. It poisoned humanity with its shameful ideology. Now it is bringing in diseases unknown even in the dark medieval ages.

Only by fighting against war and world imperialism, we can prevent humanity from dying. Imperialism involves digging the grave for the world with the help of blood-stained bayonets, but it will be buried in this very grave.

The argumentative strategy is represented by the following claims:

‘The Spanish disease’ is a creation of war and global imperialism.

If the war drags on, even more deadly epidemics and worse social disasters will develop.

Imperialism must be destroyed.

The only solution is a socialist revolution that will free the world from the contagion of imperialism and war and save humanity from destruction.

TABLE 1. Social actors, objects and phenomena and predications in the article “Spanish Disease” (Izvesia, July 16, 1918).

During the next month, Pravda and Izvestia published short articles describing the spreading disease and its economic and social ramifications.Footnote29 According to the news, Spanish flu was approaching the borders of Soviet Russia; at first, cases were being registered in Finland and then in Kharkov. Izvestia even published this information in the front-page special section containing short announcements of the main published materials.Footnote30 In our view, this is proof that the press attached great importance to the new contemporaneous epidemic.

Nevertheless, on August 11, 1918, on the second page of Izvestia, an article by a future Soviet intelligence officer, then an assistant to the newspaper secretaryFootnote31 Ilya Herzenberg was published under the headline, ‘The Spanish disease and the Russian infection.’ The author opposes the descriptors ‘Spanish disease’ and the so-called ‘Russian infection,’ the latter implying communism ideas being spread among workers and soldiers in Europe.

‘Humanity’ here is divided into 1) ‘the working class/proletariat and soldiers in the West,’ who are apathetic, war-weary, exploited, and paralyzed by the Spanish disease, in contrast to 2) ‘the working class in Soviet Russia,’ which has breathed a sigh of relief. However, both groups still face counteractions from 1) the bourgeoisie, 2) imperialists, and 3) social betrayers (see ). In this case, along with the predicative and argumentative strategies, intensification is also employed, expressed in a tag question: ‘Who will refresh the stagnant atmosphere? Who will breathe the spirit of vitality, outrage, and revolution into the apathetic working masses of the West?’

TABLE 2. Social actors, objects, and phenomena and predications in the article ‘The Spanish disease and the Russian infection’ (Izvestia, August 11, 1918).

The given article has the following significant claims as argumentation devices:

In Europe, the working class is solely affected by ‘Spanish disease’: ‘The Spanish disease is a mass influenza of the workers quite often resulting in deaths.’

Bad living conditions of workers led to the epidemic spread: ‘Militarization of factories and workshops, 10-hour working day, an abundance of surrogate foods, population density, and unprecedented nervous shocks are the conditions in which the Spanish disease is spreading rapidly.’

The bourgeoisie uses the epidemic to suppress the discontent of the proletariat: ‘The bourgeoisie in power regards any methods contributing to delaying an inevitable outburst of spontaneous indignation quite appropriate.’

Russia will cope with the Spanish disease successfully as the Soviet power takes all measures to improve the social conditions of workers’ lives:

Workers receive extra rationing. They are moved from dark, damp basements into light-cozy premises, being freed from parasitic elements. Private property is being expropriated on a large scale. The working class started to breathe freely, and if everything had not been achieved yet, they still had an opportunity to effectively struggle for their interests.

‘All Measures Have Been Taken to Find Facts … ’

On July 9, 1918, five days prior to the first news about a new global epidemic, Izvestia published a draft decree by the Council of People’s Commissars (CPC) on establishing a single body of healthcare management: the People’s Healthcare Commissariat (Narkomzdrav). The Decree was adopted two days later, on July 11, 1918.Footnote32

The first attempt to establish such a centralized structure was made in Tsarist Russia under Emperor Nikolai II in 1916; however, it failed because of medical community opposition.Footnote33 After the October Revolution of 1917, local Deputy Councils established Medical Sanitation Services, and some People’s Commissariats had their own medical panels. In addition, from Tsarist Russia, the Soviet power inherited insurance medicine and rural (zemskaya) and municipal (gorodskaya) medicines with their own hospitals and management structures.Footnote34 Thus, Narkomzdrav, guided by a doctor and an active party member, Nikolai Semashko, faced the task of uniting all these fragmented entities into a single structure.

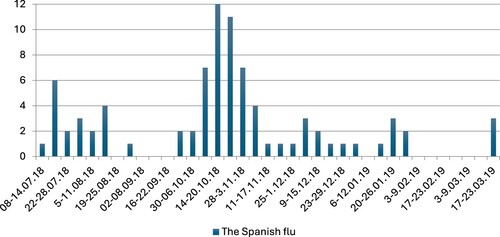

Later, Semashko recounted that this process was difficult to implement.Footnote35 Undoubtedly, fighting epidemics was at the top of the Commissariat agenda. One of its first decrees was the Resolution on vaccinating against cholera and establishing a special committee on fighting epidemics (Izvestia, August 18, 1918). Nevertheless, one could assume that during the initial months of functioning, officials were more concerned with staff and administrative problems. This was probably the cause of the unusual facts exposed in the course of our research. After the initial coverage of the Spanish flu epidemic approaching the territory controlled by Bolsheviks, Izvestia published the breaking news: ‘The Commissariat for Healthcare have been taking all measures to find facts about the Spanish disease in the nearest disease epicenters, and we guess that in the near future, it will be managed to make the public at large more aware thereof’ (August 4, 1918). However, information on the organization’s first actions regarding the epidemic was published only two months later, and until the end of September 1918, the Soviet press made practically no mention of a new disease (see ).

‘The Rest of the Day and Night was Dreadful … ’

At the beginning of the autumn of 1918, information on the Spanish flu spread only among concerned parties such as foreign countries or territories of the former Russian Empire, beyond the Bolsheviks’ control. In particular, on September 29, Izvestia informed about the disease of Fyodor Lizogub, the Head of the Council of Ministers of Ukraine. There was no mention of the spread of the epidemic in Soviet Russia.

On October 1, 1918, the first pages of Pravda and Izvestia were devoted solely to the demise of Vera Bonch-Bruevitch (Velichkina). She had occupied several administrative posts, including the position of Deputy Chairman of the Council of Medical Panels of Narkomzdrav.Footnote36 According to the memoirs of her spouse, the Secretary of CPC Vladimir Bonch-Bruevitch, at that time, she was explicitly known to have died of the Spanish flu: ‘An established doctor Mamonov came and took urgent measures but stated that it was a severe case of the Spanish disease, and he could not guarantee anything. The rest of the day and night was dreadful’.Footnote37 In that context, he mentioned that ‘in the Kremlin, people began to fall with influenza, the latter turning into pneumonia’,Footnote38 and doctors diagnosed it as the Spanish flu. The cause of her death, however, was described by the newspaper as ‘pneumonia caused by complicated influenza’ (Izvestia, October 1, 1918). Consequently, we might assume that the Bolshevik government decided not to publicly announce that a new frightening epidemic had already reached elite circles.

Nevertheless, several days later, the press began to inform that the epidemic was also raging in the Soviet Republic, with these publications setting an alarming tone. The discourse employed in these brief news articles was underscored by an intensification strategy. It made use of modal verbs such as ‘must’ and ‘should,’ directed at local authorities: ‘From Voronezh, Ryazan, Oreol, and other regions, we receive information on the so-called ‘Spanish flu.’ Local healthcare departments should take urgent measures’ (Izvestia, October 4, 1918).

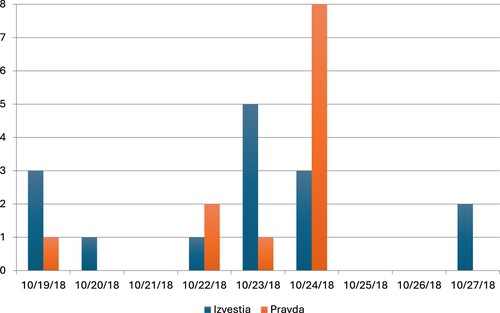

Articles were published on October 9 that admitted that the epidemic was affecting the country (Izvestia, October 9, 1918; Pravda, October 9, 1918). From that moment and throughout the next month, almost every issue of Pravda and Izvestia published information about the Spanish disease. The number of publications peaked on October 23 and 24 with five articles in Izvestia and eight in Pravda from various regions of the country (see ). However, the number of times the disease was mentioned decreased, and from mid-December, there were no articles about the Spanish flu epidemic; the disease was mentioned only along with other epidemics. In late January, the Spanish flu completely disappeared from the pages of the Soviet press (see ) up to March 18, 1919; however, during that period, the disease did not stop its spread in Soviet Russia, and in winter–spring 1919, the country experienced another epidemic wave.Footnote39

‘There are no Specific Measures of Fighting the Epidemic’

Three weeks after the death of Vera Bonch-Bruevitch, on October 20, 1918, Narkomzdrav organized ‘a large scientific meeting of doctors on the issues of studying and fighting the Spanish disease’ (further referred to as ‘Meeting’), with the announcement of the Meeting being published in Izvestia.Footnote40 Furthermore, the central press published several articles related to the Meeting, which was ‘attended by so many medical professionals, students and the public that a spacious university auditorium could not house all wanted to attend’ (Pravda, October 23, 1918). Leading scholars and medical practitioners were the speakers, and the range of topics varied widely from the disease's history of development, symptoms, and etiology to potential measures to fight the epidemic. The Meeting started at 2 pm and lasted till late evening, and ‘no opinion exchange took place due to late hour’ (Pravda, October 22, 1918). Nevertheless, in our view, the Meeting became a crucial event in shaping Soviet Russia’s medical authorities’ approaches to the problem.

Relying on these publications, as well as on the entire corpus of contemporaneous publications, we can conclude that within the first months of the epidemic, Soviet healthcare authorities faced the following problems:

Lack of Adequate Statistics on the Number of Infected

In mid-August 1918, Narkomzdrav adopted a regulation on a compulsory centralized collection of infectious disease statistics (Izvestia, August 18, 1918). At the time while this regulation was being prepared, medical authorities already knew about the Spanish disease; in addition, several days before, there was a catchy headline in the Izvestia’s front-page announcement column: ‘The Spanish disease is in Tambov governorate’ (August 14, 1918) which implied that a dangerous disease had already entered the Soviet territory. However, the long list of diseases that doctors were to inform the authorities about did not include the Spanish flu. The circular letter demanding a compulsory twice-monthly provision of information on the number of infected individuals and the death toll for the authorities was distributed by Narkmozdrav on November 2 (Izvestia, November 2, 1918).

Contradictory Data on the Death Rate

In the articles from different regions, the mortality rate varied from 10–30%. A report by leading infectiologists on the Uezds of the Moscow governorate also provides conflicting information. For instance, the Director of the Central Institute of Bacteriology in Moscow, Evgeny Martsinovsky, upon returning from Zubtsovsky Uezd, informed that the death rate reached 34.4% and was close to cholera death rate (Izvestia, October 19, 1918). However, further, in the same article, a well-known hygienist, Feodosy Kostorsky, who visited factories of Bogorodsko-Glukhovsloy Manual, speaks of a 10–15% death rate. Izvestia, following the Meeting, mentions 40%.

Simultaneously, the accuracy of these estimates has raised questions for several reasons.

Statistical Relevance

Doctor Ivanov emphasized this problem when speaking at the Meeting. As the Spanish flu symptoms coincide entirely with the flu, oftentimes ‘medics do not diagnose the Spanish flu and do not distinguish it from other types of influenza’ (Pravda, October 23, 1918), he stated, though, simultaneously, they registered a surge in the total number of those who fell with various types of colds.

Lack of Comprehensive Information on the Epidemic Spreading Abroad

Under military censorship in Europe and Soviet Russia's political isolation, the Bolshevik government might not have comprehensive information on the spread of the Spanish disease epidemic in European countries and on the measures taken by European medical authorities and their efficacy. Because of this, one of the main points of the plan proposed by the epidemiological subdivision of Narkomzdrav was as follows: ‘To send abroad a special person to get familiarized with the measures against the Spanish disease’ (Izvestia, October 27, 1918). Nevertheless, there was no further information on whether they managed to implement this mission or what results were obtained.

Still, summing up the hour-long Meeting, scholars and medics concluded that the Spanish disease was just a ‘severe form of influenza with an atypical course’ (Pravda, October 22, 1918). Moreover, the Izvestia resume made up, from the look of it by Narkomzdrav officials, sounded even more categorically: ‘There are no specific measures of fighting the epidemic’ (Izvestia, October 22, 1918).

The key argumentative assertions within these articles were as follows:

Humanity is Continually Confronted with Epidemics.

The ‘Spanish Disease’ is Simply a Severe Form of Influenza.

The Experience from Previous Similar Influenza Epidemics Indicates that the Disease Does not Discriminate by Social Status.

There are no Specific Means to Combat the Epidemic.

Probably, due to this, all the announced measures of combating ‘Spanish disease’ were limited just to administrative measures aimed at raising the number of medical staff in hospitals and enhancing hygienic propaganda among the population in the form of ‘lectures in the cinemas’ and distributing special leaflets (Izvestia, October 20, 1918).

Irrespective of the harsh measures being taken in Europe and the fact that despite informational restrictions, the world press, including the Soviet press (e.g. Izvestia, October 24, 1918), still wrote about them, such decisions seem strange and even surprising. However, to discover the reasons for this approach, Spanish disease epidemic coverage must be compared with the way the same press covered other epidemics spreading contemporaneously.

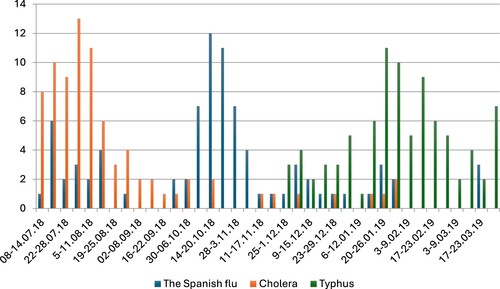

Rise in Arms Against Typhus!

Throughout the period under study, three epidemics spread throughout Soviet Russia: cholera, the Spanish flu, and typhus. At the time the initial news on the Spanish disease global spread was published, the country was fighting the cholera epidemic, which broke out in the summer of 1918 (Izvestia Narodnogo Komissariata Zdravoohranenia, 1918, №11), yet by autumn, it subsided (Izvestia, December 3, 1918). Simultaneously with the Spanish flu raging in the Soviet Republic, they published information on the onset of the typhus epidemic, and gradually the news on typhus practically replaced all the other infectious diseases on media agenda (see ). Considering publications in Pravda and Izvestia, all attention of the state apparatus was focused on fighting typhus. They took urgent measures, including building and establishing new hospitals, disinfecting public spaces with large crowds, opening baths, and providing soap and hot water. They even published the principal scheme for constructing public baths where unwashed and washed people could not mingle (Izvestia, February 5, 1919). Hence, we can assert that it was fighting the typhus epidemic, which became a primary concern for Soviet healthcare organizations.

DIAGRAM 3. The number of mentions of Spanish flu, cholera, and typhus in publications of Izvestia between July 8, 1918 and March 23, 1919 (weekly breakdown).

The first statistics on the Spanish disease epidemic were published on December 7, 1918. A small article on the last page of Izvestia mentioned that the epidemic raged through 22 governorates and ‘135,780 cases of the Spanish disease were diagnosed’ (Izvestia, December 7, 1918). However, less than a week later, the news came that the epidemic covered 31 governorates, and the number of infected from August to November was 779,323 people (Izvestia, December 12, 1918), which accounted for approximately 1% of the population residing in the territories controlled by the Bolsheviks. Simultaneously, despite initial worrisome death rate indicators, this figure was 2,43% (Izvestia, December 12, 1918). Although, compared to today, this percentage seems to be very high,Footnote41 at that time, considering the quality of Russian and then-emerging Soviet medicine, this percentage was not likely to be shocking. For instance, in late January 1919, Semashko made no secret of his joy about the fact that the typhus death rate during the ongoing epidemic did not exceed 6%; ‘this is an unprecedentedly low death rate throughout all the history of typhus,’ he stated (Izvestia, February 2, 1919). However, it is essential to note that a low fatality rate from influenza is not a relevant indicator in this context, as the high number of deaths from Spanish flu should be associated with a large number of infections.

Nevertheless, proclaiming the Spanish disease death rate allowed Semashko to argue that ‘our republic has relatively successfully done away with both cholera and the Spanish disease, which brought deaths to many more people in civilized Western Europe than we had’ (Izvestia, January 26, 1919).

To Destroy Capitalist Exploitation

As we know, the Bolsheviks considered all existing problems and ways of addressing them solely through the prism of Marxist doctrine, that is, in terms of class struggle.Footnote42 Consequently, the fight against epidemics in Soviet Russia could not be approached differently.

In his first newspaper article after taking the chair, Semashko juxtaposed the cholera-fighting measures and social-political decisions of the Bolsheviks. According to him, expropriating apartments of bourgeois elements in order to improve proletariat life should be done ‘never minding a ‘sacred’ principle of private property immunity and consequential privileges.’ He also emphasized the role of the surplus appropriation system (Prodrazverstka), implemented thanks to the ‘bread crusade’ aimed at saving the country from hunger (Izvestia, July 23, 1918).

Furthermore, fighting typhus was placed in the framework of class struggle. Semashko stated that the struggle to improve sanitation conditions for poor people was impossible without destroying capitalist exploitation (Izvestia, January 26, 1919). Even the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin, who paid almost no attention to medical issues, in his article published in Pravda (January 28, 1919), tied the problem of providing Soviet Russia with food to fighting the epidemic of typhus.

Thus, it is evident that for Bolsheviks cholera and typhus were ‘class’ diseases, primarily affecting people from lower social classes. As a result, combating such diseases was a fight for the triumph of the proletariat and a fight to implement the ideas of communism.

Meanwhile, as Izvestia wrote, the Spanish disease ‘did not discriminate a social status’ (October 22, 1918). Hence, it had a significant shortcoming in that it was not in line with an ideological war. Initially, the Bolsheviks attempted to incorporate the disease into their standard ideological patterns. However, after clarifying the etiology, it became clear that these patterns could not be applied.

Furthermore, for the Soviet government, the measures taken by the Western governments were either unacceptable or impossible for purely economic reasons.

Wearing masks

Soviet Russia was experiencing a severe economic crisis and the greatest deficit not only in food but also in manufactured goods. Gauze was not enough, even for the wounded Red Army soldiers.Footnote43

Crowded public areas closures (cinemas, theaters, etc.) and public meetings ban

The Bolshevik government had been in power for less than a year and its position was too shaky. Pravda and Izvestia regularly published announcements and further reports on numerous meetings, concerts, and congresses of the representatives of various social and professional groups. Public events of this kind were the primary means of campaigning among the Bolshevik’s target audience, that is, workers and peasants. The article by one of Narkomzdrav’s officials Alexey Sysin where he cautioned against such measures as ‘closing all entertainment places, cinema houses, concerts, theaters, etc.’ (Izvestia, March 4, 1919) could be another proof.

On March 16, 1919, Yakov Sverdlov, the Chairman of the ARCEC, the second person in the Soviet hierarchy, passed away. Pravda and Izvestia dedicated their front pages to life and death. However, only two articles of Izvestia mentioned that his unexpected death was caused by ‘some horrible disease called ‘Spanish flu,’ the consequence of the world massacre’ (Izvestia, March 18, 1919), while Pravda did not mention this fact at all. Thus, the authorities found it disadvantageous to focus on Sverdlov’s diagnoses. Consequently, it did not change the authorities’ attitudes toward the pandemic, and practically any information on the disease disappeared from the Soviet press. Only the Izvestia’ column ‘Last news,’ with a month delay, published a short, one-sentence message that a well-known actress Vera Kholodnaya died of the Spanish flu in Odessa (Izvestia, March 20, 1919). The last wave of the epidemic ended in spring.

Discussions and Conclusion

Our research revealed that ideological factors influenced the nature of the Soviet press discourse related to the Spanish flu, while reporters and Bolshevik authorities were primarily guided by political expediency. The Spanish flu discourse can be conceptualized as a spiral, characterized by 1) an initial attempt to assimilate the novel, unknown disease into the ideological framework, 2) mounting concerns amid the rapidly escalating epidemic, and 3) its reintegration into the narrative of the Soviet authorities’ successful combat against infectious diseases.

Undoubtedly, the Spanish flu epidemic in Soviet Russia was overshadowed by contemporaneous political, geopolitical, and social issues, as well as by other concurrent epidemics. Initially, the development of the medical system in the new Bolshevik state was geared toward creating conditions conducive to the prevention of infectious diseases, providing medical assistance to the indigent, invention of new vaccines, introduction of compulsory vaccination and disseminating hygiene education among illiterate people.Footnote44 Over the subsequent decades, vertical management structures have been established, including a system of sanitary-epidemiological stations and tuberculosis and venereal disease dispensaries, which actively control and prevent the spread of epidemics.Footnote45 Consequently, the systematic fight against and prevention of epidemics has significantly reduced the incidence of these diseases.

In the early years of Soviet power, the Bolsheviks successfully utilized the foundations as well as medical and scientific personnel prepared during the Tsarist era.Footnote46 However, many professionals and scientists who disagreed with the new regime were later repressed.Footnote47 The construction and equipment of new hospitals faced shortages in resources and qualified personnel, which led to very low levels of medical aid.Footnote48 Moreover, the provision of medical assistance in the early years of the Soviet state retained an exclusively class-based approach, according to which people were categorized based on their utility in the new order.Footnote49 The Soviet sanitation propaganda (Sanprosvet) also served as a collection of political messages that simultaneously proclaimed the achievements of socialist healthcare both inside the country and abroad.Footnote50

Therefore, the inability to fit the struggle against the Spanish flu into the ideological canvas of Bolshevik propaganda, coupled with a lack of understanding regarding how to effectively cope with it, led to its suppression in public discourse. However, media coverage of the Spanish flu in territories beyond Bolshevik control and how it differed from Bolshevik discourse requires further research and analysis.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Petr Gulenko

Petr Gulenko, Department of Sociology, Faculty of Humanities, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic

Notes

1 Berche, “The Spanish flu”.

2 Phillips and Killingray, The Spanish Influenza.

3 Phillips, “The recent wave”.

4 Beiner, Pandemic Re-Awakenings.

5 Breitnauer, The Spanish Flu.

6 Bolshakova, “The Spanish Flu”.

7 Wodak, “The semiotics”.

8 Prutkaya and Khotina, “Guidelines of Campaigning”.

9 Johnson and Mueller, “Updating the accounts”.

10 Johnson, Britain and the 1918–19 Influenza.

11 Patterson and Pyle, “The geography”.

12 Spinney, Pale rider.

13 Barry, The Great Influenza.

14 Worobey, Cox and Gill, “The Origins”.

15 Johnson and Mueller, “Updating the accounts”.

16 Vasyliev and Vasylieva, “From the history of the fight”.

17 Vasyliev and Vasylieva, “To the history”.

18 Trilla et al., “The 1918 “Spanish Flu” in Spain”.

19 Radusin, “The Spanish flu, part I”.

20 Witte, “The Plague”.

21 Johnson, “The overshadowed killer”.

22 Blakely, Mass mediated disease.

23 Spratt, “Science”.

24 Ezzy, Qualitative analysis.

25 Reisigl and Wodak, “The discourse-historical approach”

26 Wodak, “The semiotics”.

27 Wodak et al., “The discursive construction”.

28 Molchanov, Newspaper press, 51.

29 Eg., Izvestia, 20 July 1918, 31 July 1918; Pravda, 17 August 1918 among others.

30 See Izvestia, 18 July 1918, 23 July 1918.

31 Alekseev et al., The Encyclopaedia, 223-224.

32 Sorokina, The history of medicine, 62.

33 Yegorysheva, “The importance of works of the GYE”.

34 Vasyliev and Vasylieva, “From the history of the fight”.

35 Semashko, Selected Works.

36 Sorokina, 63.

37 Bonch-Bruevitch, Vospominania o Lenine, 1969, 434.

38 Ibid.

39 Spasennikov, “Spanish flu in Russia”.

40 Izvestia, 18 October 1918, 19 October 1918.

41 Johnson and Mueller, “Updating the accounts”.

42 Eg., Lenin, Polnoe sobranie sochineniy, 41.

43 Spasennikov, “Spanish flu in Russia”.

44 Zatravkin and Vishlenkova, “The principles”.

45 Chistenko and Eliashevich, The history.

46 Davis, Russia.

47 Topolianskyi, “The end”.

48 Zatravkin et al., "A radical turn”.

49 Yakovenko, “The Health”.

50 Starks, “Propagandizing”.

References

- Alekseev, M., A. Kolpakidi, and Y. Kochik. The Encyclopaedia of Military Intelligence Service. 1918-1945. Moscow: Kuchkovo pole, 2012.

- Barry, M. The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. New York: Viking Penguin, 2004.

- Beiner, G., ed. Pandemic Re-Awakenings: The Forgotten and Unforgotten ‘Spanish’ Flu of 1918–1919. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Berche, P. “The Spanish flu.” La Presse Médicale 51, no. 3 (2022): 104127.

- Blakely, D. E. Mass Mediated Disease: A Case Study Analysis of Three flu Pandemics and Public Health Policy. Lexington: Books, 2006.

- Bolshakova, O. “The Spanish Flu: Unlearned Lessons.” Trudy po Rossievedeniu 8 (2021): 82–105.

- Bonch-Bruevitch, V. Vospominania o Lenine [Memories of Lenin]. Moskva: Nauka, 1969.

- Breitnauer, J. The Spanish Flu Epidemic and its Influence on History. Yorkshire: Pen and Sword, 2020.

- Chistenko, G.N., and E.G. Eliashevich. The History of Domestic Hygiene and Epidemiology in the XX Century. Minsk: BGMU, 2011.

- Davis, J.P. Russia in the Time of Cholera: Disease Under Romanovs and Soviets. London: I.B. Tauris, 2018.

- Ezzy, D. Qualitative Analysis. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Johnson, N. “The Overshadowed Killer: Influenza in Britain in 1918–19.” In The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919, edited by D. Killingray, and H. Phillips, 132–155. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Johnson, N. Britain and the 1918–19 Influenza Pandemic: A Dark Epilogue. London: Routledge, 2006.

- Johnson, N.P., and J. Mueller. “Updating the Accounts: Global Mortality of the 1918-1920 Spanish Influenza Pandemic.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 76, no. 1 (2002): 105–115.

- Lenin, V. Polnoe Sobranie Sochineniy [The Complete Collection of Works]. Moskva: Izdatelstvo politicheskoy literatury, v. 21, 1968.

- Molchanov, L. Newspaper Press at the Times of Revolution and the Civil War (October 1917-1920). Moscow: Izdatprofpress, 2002.

- Patterson, K., and G. Pyle. “The Geography and Mortality of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic.” Bulletin of the History of Medicine 65, no. 1 (1991): 4–21.

- Phillips, H. “The Recent Wave of 'Spanish' Flu Historiography.” Social History of Medicine 27, no. 4 (2014): 789–808.

- Phillips, H., and D. Killingray. eds. The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918–19: New Perspectives. ct: Routledge, 2003.

- Prutkaya, Т., and J. Khotina. “Guidelines of Campaigning and Propaganda Work of Bolsheviks.” Research Papers of Kuban State Technological University 9 (2016): 217–226.

- Radusin, M. “The Spanish flu, Part I: The First Wave.” Vojnosanitetski Pregled 69, no. 9 (2012): 812–817.

- Reisigl, M., and R. Wodak. “The Discourse-Historical Approach.” In Methods of Critical Discourse Studies, edited by R. Wodak, and M. Meyer, 87–121. London: Sage, 2015.

- Semashko, N. Izbrannye proizvedenia. [Selected Works]. Moscow: Medicina, 1967.

- Sorokina, T. The History of Medicine. Moscow: Academia, 2008.

- Spasennikov, B. “Spanish flu in Russia (1918-1921).” Bulletin of Semashko National Research Institute of Public Health 3 (2021): 22–31.

- Spinney, L. Pale Rider: The Spanish flu of 1918 and how it Changed the World. New York: Public Affairs, 2017.

- Spratt, M. “Science, Journalism, and the Construction of News.” American Journalism 18, no. 3 (2001): 61–79.

- Starks, T.A. “Propagandizing the Healthy, Bolshevik Life in the Early USSR.” American Journal of Public Health 107 (2017): 1718–1724.

- Topolianskyi, V. “The End of the Pirogov Society.” Rossiya XXI 4 (2014): 168–191.

- Trilla, A., G. Trilla, and C. Daer. “The 1918 “Spanish Flu” in Spain.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 47, no. 5 (2008): 668–673.

- Vasyliev, K., and O. Vasylieva. “To the History of the Fight against the Spanish Pandemic: Kiev and Kharkiv.” Shidnoevropejskij zurnal vnutrisnoi ta simejnoi medicini 2 (2020): 31–37.

- Vasyliev, K., and O. Vasylieva. “From the History of the Fight with the Spanish Desease in Soviet Russia.” Bulletin of Semashko National Research Institute of Public Health 3 (2021): 10–15.

- Witte, W. “The Plague That was not Allowed to Happen: German Medicine and the Influenza Epidemic of 1918–19 in Baden.” In The Spanish Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919, edited by D. Killingray, and H. Phillips, 49–57. London: Routledge, 2003.

- Wodak, R. “The Semiotics of Racism: A Critical Discourse-Historical Analysis.” In Discourse, of Course: An Overview of Research in Discourse Studies, edited by J. Renkema, 311–326. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2009.

- Wodak, R., R. De Cillia, and M. Reisigl. “The Discursive Construction of National Identities.” Discourse & Society 10, no. 2 (1999): 149–173.

- Worobey, M., J. Cox, and D. Gill. “The Origins of the Great Pandemic.” Evolution, Medicine, and Public Health 2019 (January 2019.

- Yakovenko, V.A. “The Health of Population and Social Stratification in N.A. Semashko’s Publicistic Writing (1918–1928).” Russia and the modern world 3 (2020): 191–203.

- Yegorysheva, I. “The importance of works of the GYE. Rhein commission for public health in Russia.” Problemy social’noy gigieny, zdravoohranenia i istorii mediciny 2 (2013): 54–57.

- Zatravkin, S.N., and E.A. Vishlenkova. “The Principles of the Soviet Medicine: History of Establishment.” Problems of Social Hygiene, Public Health and History of Medicine 28, no. 3 (2020): 491–498.

- Zatravkin, S., E. Vishlenkova, and E. Sherstneva. ““A Radical Turn”: The Reform of the Soviet System of Public Healthcare.” Quaestio Rossica 8, no. 2 (2020): 652–666.