Abstract

Most spatially-oriented studies about health, safety and service provision among women in street sex work have taken place in large urban cities and document how the socio-legal and moral surveillance of geographical spaces constrain their daily movements and compromise their ability to care for themselves. Designed to contribute new knowledge about the broader socio-cultural and environmental landscape of sex work in smaller urban centres, we conducted qualitative interviews and social mapping activities with thirty-three women working in a medium-sized Canadian city. Our findings demonstrate a socio-spatial convergence regarding service provision, violence, and stigma, which is common in sex trading spaces that double as service landscapes for poor populations. Women in this study employ unique agential strategies to navigate these competing forces, many of which draw upon the multivalent uses of different urban spaces to optimise service access, reduce the propensity for violence, and manage their health with dignity. Their use of the spatialised term ‘everywhere’ as an idiom of distress regarding issues of power, agency and their desire to take part in wider civic discourse are also explored. These data contribute new insights about spatialised notions of health, stigma, agency, and subjectivity among women in sex work and how they manage ‘risky’ environments.

Résumé

La plupart des études orientées sur les espaces dédiés à la santé, la sécurité et la fourniture de services chez les femmes exerçant le travail du sexe dans la rue ont été conduites dans de grands centres urbains et documentent la manière dont la surveillance sociojuridique et morale des espaces géographiques restreint les mouvements quotidiens de ces femmes et compromet leur capacité à prendre soin d’elles-mêmes. En ayant pour objectif d’obtenir un nouvel éclairage sur le paysage socio-culturel et environnemental général du travail du sexe dans de plus petits centres urbains, nous avons conduit des entretiens qualitatifs et des activités de cartographie sociale avec trente-trois femmes travaillant dans une ville canadienne de taille moyenne. Nos résultats démontrent l’existence d’une convergence socio-spatiale de la fourniture de services, de la violence, et du stigma, celui-ci étant fréquemment présent dans les espaces de commerce sexuel qui servent également d’espaces de dispensation de services aux populations pauvres. Dans cette étude, les femmes utilisent des stratégies agentielles uniques pour progresser entre ces forces concurrentielles, dont beaucoup s’appuient sur les utilisations multivalentes de différents espaces urbains, pour optimiser l’accès aux services, réduire la propension à la violence et gérer leur santé avec dignité. Leur utilisation du mot spatialisé « partout » comme un idiome de la souffrance, relativement aux questions de pouvoir, de capacité d’agir et de désirs de contribuer au discours civique est également explorée. Ces données apportent de nouveaux éclairages sur les notions spatialisées de la santé, du stigma, de la capacité d’agir et de la subjectivité chez les travailleuses du sexe et sur la manière dont elles gèrent les environnements « risqués ».

Resumen

La mayoría de estudios con una orientación espacial sobre salud, seguridad y prestación de servicios a mujeres que se dedican al comercio sexual en la calle han tenido lugar en grandes ciudades urbanas y muestran el modo en que la vigilancia sociolegal y moral de los espacios geográficos limita sus movimientos diarios y compromete su capacidad para poder cuidarse de ellas mismas. Con el objetivo de contribuir con nuevos conocimientos sobre el amplio paisaje sociocultural y medioambiental del trabajo sexual en centros urbanos más pequeños, llevamos a cabo entrevistas cualitativas y actividades de localización geográfica en un ámbito social con treinta y tres mujeres que trabajan en una ciudad canadiense de tamaño medio. Nuestros resultados demuestran una convergencia socioespacial con respecto a la prestación de servicios, violencia y estigma, que es habitual en los espacios de comercio sexual que hacen las veces de paisajes de servicios para poblaciones pobres. Las mujeres en este estudio emplean estrategias funcionales únicas para gestionar estas fuerzas competitivas, muchas de las cuales se basan en usos multivalentes de los diferentes espacios urbanos con la finalidad de optimizar el acceso a los servicios, reducir la predisposición a la violencia y gestionar su salud con dignidad. También analizamos el uso del término espacializado ‘en todas partes’ como una expresión de angustia con respecto a las cuestiones de poder, capacidad de acción y deseos de contribuir al discurso cívico. Estos datos contribuyen con nuevas perspectivas sobre las nociones espacializadas de salud, estigma, capacidad de acción y subjetividad en mujeres que se dedican al trabajo sexual y sobre cómo gestionan los entornos “arriesgados”.

Introduction

Contemporary legislative and ideological discourses about sex work have shifted from a focus on labour, gender and human rights in the 1990s to a concern with risk and vulnerability in the last decade. Indeed, Canadian and global discourses often conflate sex work with human sexual trafficking (Brock Citation2009; Parent et al. Citation2013). Violence and health are predominant themes in research, community interventions and policy domains, where these concepts are framed as phenomena experienced at the individual level and relationally through intersecting socio-political and systemic forces (Dewey and St. Germain Citation2016; Ferris Citation2015; Knight Citation2015; van der Meulen, Durisin and Love Citation2013). Within this interdisciplinary setting, enquiry into how space shapes the experiences of women in sex work in relation to violence, access to health care and social services is emerging as an increasingly important field of study (Orchard et al. Citation2016).

Social geographers have long been interested in the interplay between physical spaces, the socio-political meanings attributed to them, and the ways in which people process as well as experience space/place (McDowell Citation1999; Sharp Citation2009; Wright Citation2010). These scholars also examine how gentrification and municipal safety policies collide in urban terrains that double as community spaces and sex working areas, which often produces heightened concerns about the moral standing of such neighbourhoods and the people who live within its boundaries (Boels and Verhage Citation2016; Mathieu Citation2011; Pitcher et al. Citation2006; Weitzer and Boels Citation2015). Health researchers interested in the spatialisation of sex work explore various issues, including the distribution of HIV and other embodied risks in poor urban neighbourhoods and how the spatialised behaviours of clients and police affect sex workers’ safety (Deering et al. Citation2014; Goldenberg et al. 2017; Katsulis Citation2008; Shannon et al. Citation2008). Some of these projects portray the health risks associated with sex work and drug-using areas as generalised features of the places in which these activities occur. Yet, spaces are not experienced uniformly, and they do not produce the same kinds of socio-economic, emotional, or material outcomes for all who move through or live in them. This is reflected in Lowman’s (Citation2000) landmark paper about discourses of disposability, where he finds variation in the murder rates of sex workers in Vancouver by neighbourhood. Other studies document how certain spaces are stigmatised because they are occupied primarily by marginalised groups. Such “territorial stigma” impedes these groups’ ability to access social and health services (Aral, St. Lawrence, and Uusküla 2006, Collins et al. Citation2016), increases their risk for violence, and exacerbates experiences of discrimination. However, these processes can be circumvented. Fast et al. (Citation2010) examine the spatial tactics street youth in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside use to distance themselves from the disparaging geo-social and moral characteristics associated with this neighbourhood and how they carve out places of their own to belong.

This paper builds upon these foundational sex work and social/feminist geography studies, particularly those that examine gender, health, power, and subjectivity (Draus, Roddy, and Asabigi Citation2015; Hail-Jares, Shdaimah, and Leon Citation2017; Hubbard Citation2001). We aim to contribute new knowledge about how women in sex work conceive of space within the socio-spatial confines of life in civic environments from which they are often excluded. Using qualitative interview data from thirty-three women in street-based sex work in a medium-sized Canadian city, we focus on the women’s constructions of space and explore how they exercise various forms of spatialised agency to circumvent the stigmas associated with sex work and drug-use behaviours. We also unpack the emic terms they employ to talk about the exigencies of life in a medium-sized city with few safe, women-only services that align with the needs of women in street-based sex work who struggle with addictions issues. The study participants expressed their frustrations in spatial terms, frequently asserting that negative experiences with service provision, violence, and safety-related issues take place “everywhere”. In this setting, everywhere emerges as an idiom of distress - a way of talking about lives that are spatially circumscribed, often unsafe, and where they are offered few opportunities for civic engagement. Although idioms of distress have been associated with individualised, pathological responses to socio-cultural change (Scheper-Hughes and Lock Citation1987), we frame everywhere as a communicative tool through which social and individual anxieties related to issues of power as well as socio-spatial exclusion are expressed (Kaiser et al. Citation2015).

Methodology

Study setting

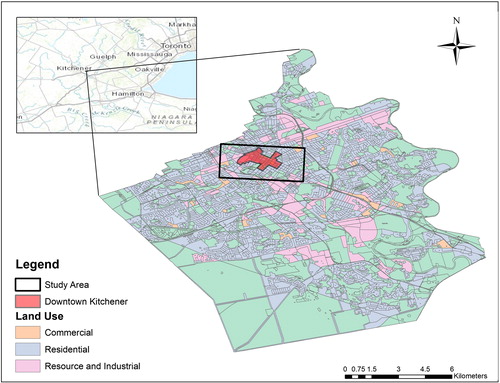

This project is set in an industrialised region in Ontario that is home to numerous automotive factories and a diverse manufacturing sector (see ). Over the last fifteen years, the economy has undergone significant change and the industrial sectors are now overshadowed by the technology market. National and international technology companies have moved into the area due to its affordable real estate, the universities in the region, and the presence of a high calibre technical workforce. This development has ushered in significant socio-economic and cultural change and is a very contentious issue, viewed as ‘revitalisation’ by some and aggressive, capital-driven gentrification by others (Macdonald Citation2017). The economic transformation is primarily occurring in the cities of Kitchener and Waterloo which are often spoken about in singular terms as ‘Kitchener-Waterloo’ and are home to approximately 460,000 people. Study participants spend most of their time in Kitchener and live primarily downtown where the street-based sex work scene is located, along King Street, Victoria Park and the low-income/transitional Cedar Hills neighbourhood.

Data collection

The primary study objective was to gather data about health care and social services, physical and sexual violence, and how space shapes the lived experiences of women in street sex work across these domains of life. We had originally aimed to include transgender women but their very small numbers in street-based settings and issues of stigma in a smaller community precluded our recruitment of this population. We employed purposive sampling techniques and placed recruitment posters at local agencies that serve women in street-based sex work. Staff members at these organisations helped spread the word about our study. Inclusion criteria were intentionally broad to ensure a robust sample (i.e. 18–60 years of age, living in the Kitchener-Waterloo area, have been or currently involved in sex work). Between March 2015 and May 2016, thirty-three individual interviews and mapping exercises were conducted with participants selected for the study. The interviews ranged from thirty to ninety minutes and took place at social service agencies and restaurants selected by participants. Prior to beginning the interviews, we described the project aims and our relative expertise in the fields of sex work research and service provision. Voluntary participation, anonymity, and on-going consent were also discussed. The women’s feedback on the research experience was very positive: “It was a learning experience… You’re teaching me that I’m not the only one out there” (Thea); “I enjoyed it, I laughed from noticing everything happens on King Street. I hope I help people” (Taylor); “It was very easy, you guys made me feel real comfortable” (Freya).

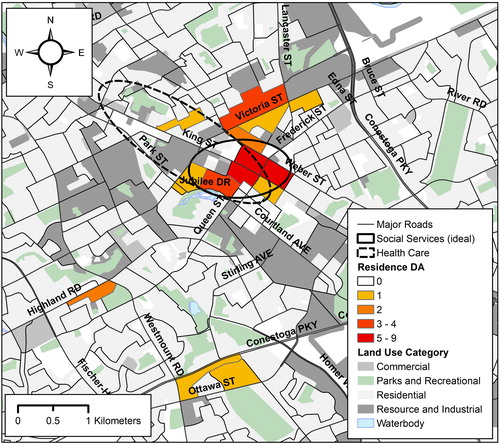

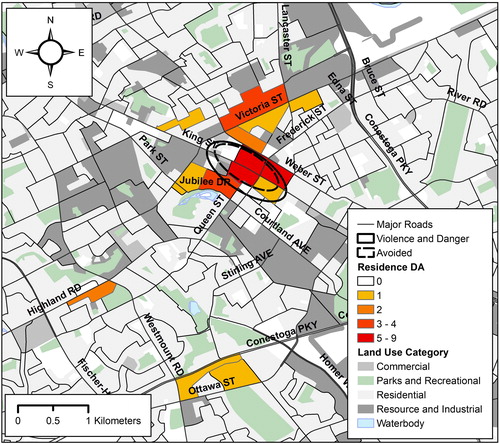

During the mapping exercises, each participant was provided with a map of downtown Kitchener-Waterloo and surrounding areas where most participants live, where most health and social services are located, and where street-based sex work tends to take place. Each participant was asked the following questions, which were designed to inform the study aim of understanding the socio-cultural and environmental organisation of sex work in Kitchener-Waterloo: (1) Can you show me where you live?; (2) Where does most street-based sex work take place?; (3) Where do you work?; (4) Where do you access health services?; (5) Where should more or better health services should be located?; (6) Where do you access social services?; (7) Where should more or better social services should be located?; (8) Have you experienced violence or dangerous experiences while working?; (9) Are there certain areas you avoid or stay away from while working?; (10) Can you mark where other aspects of street culture are concentrated; that is, drug trade, police surveillance?

Women marked their responses to each question in different coloured markers on the maps provided and these data were then analysed using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) procedures (described below). The mapping exercises took 15–20 minutes to complete and, along with the interviews, they were audio-recorded with the participant’s consent. The second author conducted the interviews and mapping exercises and the first author assisted in these activities and was the project lead. This paper features the experiences of thirty-three women with experience, past and present, in street-based sex work in our study site, which accounts for approximately one third of the total estimated number of women working in the area (n = 100). The women received CA$60 for their participation and the project received Ethics Approval from the University of Western Ontario, the lead author’s home institution.

Data analysis

In the analysis of the social mapping data, we created a set of individual layers in a geographic information system database. All mapping and spatial analyses were conducted with ArcGIS 10.2 (Esri, Redlands, CA, USA). Each layer contained geocoded location data corresponding to the questions asked during the mapping portion of interviews. To protect the privacy of participants, the locations indicated for question (1) pertaining to place of residence were linked to 2011 census boundary files for dissemination areas (DA) (Statistics Canada Citation2013). The DAs highlighted in were home to 1–3 study participants each. Standard deviational ellipses were calculated to facilitate comparisons of locations indicated in response to all other questions. These ellipses are based on calculating the standard deviation of points from the mean centre in two dimensions separately (x and y coordinates). The resulting ellipses contain approximately 68% of all locational data points used in a calculation and provide an informative representation of the area within which corresponding activities are located. Finally, the 2011 census road network file (Statistics Canada Citation2015) and land use classification data from DMTI Spatial (Markham, ON, Canada) were used to illustrate geographic features of interest.

Data analysis of the textual information stemming from the mapping activities was organised according to six principles for thematic analysis developed by Braun and Clarke (2006), beginning with familiarisation with the data by closely reading the interview transcripts and mapping information. The first, fourth, and last team members jointly coded several interviews to reach consensus regarding the relevant GIS and textual information about how space shaped participants’ perceptions of service provision, violence and avoidance behaviours. These data were then organised into master code files, which were reviewed using more refined, line-by-line coding to search for and review the emergent themes. Theoretical insights from the fields of critical feminism and medical anthropology were employed during the analysis, particularly those that focus on understanding how systemic and everyday factors shape women’s lived experiences (Scheper-Hughes and Lock Citation1987).

Findings

Socio-demographic characteristics

The women in our study were between 18 and 55 years old, with an average age of 34 years. The majority identified as White, while a minority identified as Indigenous, and two participants identified as women of colour. Most participants had finished high school, and some had taken college courses for nursing, accounting and medical technician training. One third of the sample came originally from Kitchener and most had grown up in nearby towns or small cities. Two participants were from other Canadian provinces and two immigrated from the Caribbean. Among non-locals, their time in the area varied from two months to thirty years. Their reasons for residing in the study area included: family, employment opportunities (including sex work for one participant), boyfriends, criminal justice issues (i.e. running from the law and court mandated drug treatment), social services, fleeing abusive living situations, desire to live in a smaller city and education. For others, no specific reason was provided, and one woman said: “I don’t know, I just ended up here.”

The women struggled with securing safe housing and many have experienced homelessness and emergency shelter stays at some point in their lives. At the time of the study, five participants lived in motels and these locales were also among the primary places where their sex work occurred, along with cars, clients’ homes, parks and massage parlours. The duration of participants’ time in sex work varied considerably, between two months and twenty years, with an average of five to six years. The reasons for their participation in sex work were equally diverse. While drug use was a driving force in most women’s lives, other issues like relationship break-up, poverty, the allure of making good money, and excitement also shaped their decisions to do sex work. In conjunction with sex work and other informal employment activities, most women receive government financial support. The characteristics of our sample are comparable to other Canadian street-based studies, particularly in terms of age and racial identities (Ferris Citation2015; Goldberg et al. 2017; van der Meulen, Durisin, and Love Citation2013).

Health services

Participants accessed health services in hospitals, harm reduction clinics, sexual and reproductive health services, counselling and, in several cases, their family doctors, as Cara described: “The hospital, methadone…and the Downtown Health Centre.” Similarly, Evelyn said: “Okay so the hospital…And the Y[WCA] on Frederick Street. So right across the Y was a place to give me needles and I use that.” Several women identified food as a critical health need. In Kitchener ‘The Soup Kitchen’ is an agency that offered good quality food, housing assistance and other services that made it a primary locale for our participants and other marginalised people in the city. As Lily put it, “I go to The Soup Kitchen. I also go to Roof … They have an actual nurse that comes in and she can give birth control”. These agencies were located in or near downtown, which is also where women identified a need for additional health services: “Where it’s convenient, right in the heart of downtown” (Thea); “Kitchener market. There should be a health clinic on King… because King Street is the main street” (Taylor). Pamela said health services should be “everywhere” to reduce wait times and ensure equitable access: “How about like everywhere! I think it would be so much easier and then they wouldn't be busy.”

That participants wanted more health services in the downtown areas where such services were already being offered is an important finding which reflects the need for more health services in the places sex workers live, work, and regularly frequent. Their thoughts about health and how these services were offered may have also affected their dissatisfaction with current health-specific services. Women consistently interpreted our questions about health needs and the spaces they access to manage health in biomedical terms, and their responses focus on reproductive health, needle exchange, and methadone that are accessed in hospitals and clinics. Although many social service agencies in the downtown core provided some of these health services, the women may not have been accessing them regularly because they do not expect to find health services in those locations. From their perspectives, health needs and social needs were separate issues.

Although most participants expressed a desire for more centrally located health services, this was not true for all women and all types of services. Some preferred needle exchanges and HIV/STI clinics to be located outside of the core areas: “Not right downtown but possibly right on the outskirts, you know” (Petra). This reflected a preference for accessing services associated with addictions, sex/work, and HIV away from the highly populated downtown core, where they were visible and less able to manage these aspects of life/work with discretion. This was also an example of how women sought to resist and redistribute the territorial stigma they experienced when using these services in plain sight: “You don’t want it to be on the main street because nobody wants to be seen walking into one of those, right” (Baya). Similarly, when referring to HIV-specific facilities, Alex said: “It doesn’t need to say outside because everybody doesn’t need to know everybody’s business.” Yet women balanced the need for privacy with the importance of convenience. Nina noted that sex work-specific services should be located near their work environment: “If it's for sex workers or whatever it should be close to where [they work].”

Social services

Women in this study identified twenty-two unique social services they accessed near or within downtown Kitchener. They utilised agencies that provide multiple on-site services most frequently, particularly those that helped with housing (emergency shelters, homelessness, housing placement), mental health issues, addictions, and counselling. Some agencies tailored their services for women, youth, refugees, people with disabilities, and families. A few of these organisations were faith-based. Other organisations that the women accessed regularly provided supports for sexual assault, methadone, HIV/HCV and government assistance.

Study participants wanted to see additional social services in the core areas close to The Soup Kitchen: “Near The Soup Kitchen for sure, because that’s where a lot of people go” (Thea); “Everything should be at The Soup Kitchen” (Steffanie). One woman identified a lack of safe spaces to talk about her experiences in sex work as a gap in social service provision, noting that our interview was the first time anyone had spoken with her about sex work:

King Street is a very big street…I feel they should have stuff like what you're doing right now. They should be able to have them available, like you, how you came here, and we are able to talk. I have been doing it for five years and this is the first time I talked to somebody about it (Taylor).

This need identified by Taylor might also suggest that service providers could work toward creating an atmosphere where women in sex work feel comfortable discussing their work-related concerns. This also suggested that the sex work community might benefit from the creation of a space where they could talk about their common concerns and organise as self-advocates.

Women’s preferred location for social services was driven by the desire for convenience, limited transportation options, poverty, and privacy. Some participants also indicated that they would like to have a say in where they acquire services and they want to be provided with clear accessible information about where and what services are offered. Alex reiterated the importance of offering social services in the core areas because they are most accessible to those who walk everywhere and cannot afford a bus pass1: “King Street, Duke, it needs to be accessible to people to get to on foot…Bus passes are a privilege, right.” Participants’ articulation of a need for more services in the spaces where they already exist echoed their responses about prospective health services. They want and need more service options ‘everywhere’: “I'm just gonna go with everywhere” (Petra).

Two participants recommend that social services designed for sex workers should be downtown or in Cedar Hills, a part of the city not discussed in conversations about health services. This is a lower income neighbourhood known locally as a rough place where sex work, drug use, and violence are common. One woman proposed that services are needed: “Somewhere down on King and Eby, like King and Cedar Hills or King and Eby, where they [sex workers] are” (Sage). Another mentioned the downtown Bus Terminal, which houses local bus and regional trams and is a hub of activity among street-involved people: “At the terminal because that's where a lot of low income people run to” (Freya).

Violence

In the social mapping exercise, women identified fifteen unique areas of Kitchener as places that were known to be dangerous and/or where they have experienced violence. Apart from Victoria Park and “the whole thing” these places were all located in downtown Kitchener, where most women lived and accessed health and social services. Although these discussions about violence pertained primarily to their experiences while working, this was not always the case and the prevalence of violence in the spaces where women accessed services is an important finding.

Health and social services are often offered in socio-economically depressed areas where many street-based populations live and spend time, with the intention to support them or (to use harm reduction parlance)’meet them where they are at.’ However, other studies demonstrate that this practice can exacerbate marginalised groups’ struggles for health and survival by ensuring their territorial circumscription among other poor, ill and sometimes violent people who can pose considerable risks to them (Bourgois and Schonberg Citation2009; Dewey and St. Germain Citation2016; Fast et al. Citation2010). This socio-spatial ghettoisation can lead to service aversion and compromised health and feed into entrenched stereotypes about core areas and the people who spend time there as constituent elements of the “’risky city’- where homelessness, vice, and the diseases of urban health are perceived as rampant” (Knight Citation2015, 31). Our participants experienced these discriminatory associations frequently and this is one of the reasons they suggested moving stigmatising services related to sex work and drug use from downtown to Cedar Hills or Victoria Park, where the sex trade and drug trading, as well as use, were more readily normalised. However, as areas of higher criminal activity these neighbourhoods can be dangerous for the very reasons they offer protection, which reveals additional complexities as women navigate their health and safety across competing socio-spatial terrains.

The location mentioned most frequently as a place of violence was Hall’s Lane, a laneway that runs parallel to King Street that was a key thoroughfare in the 19th century. However, due to population growth as well shifting industrial and economic developments, other streets in the core area have usurped its prominence. Although still used by many residents, present-day Hall’s Lane is a secluded space that is not visible from the main downtown streets:

A lot of the unsafe situations you’re going for, you can’t really highlight them because they are all the little alleys behind King…Those are the ones that you gotta watch out for [Hall’s Lane?] …Yeah, that’s one where girls will not willingly go and that’s the best place to put yourself in danger (Baya).

Participants employed several techniques to mitigate the violence they experienced while working. These included screening clients carefully, only going with clients known to them or others in their social circle, adopting aggressive behaviours (i.e. being pushy and rude so undesirable clients would lose interest) and having people nearby as lookouts. Women also discussed self-medicating with analgesic and/or illicit substances as a strategy to reduce the fear or anxiety that could be associated with working on the street. They also employed several spatialised strategies, such as avoiding certain tracts of the downtown core that are known to be rough, especially during the evening: “I won’t walk downtown at night. Like I am lucky to walk downtown alone during the day” (Pamela). For other women like Jocelyn, leaving the city was perceived as risky: “I don’t go anywhere out of the city.” Regina provided additional insights about the relationship between outdoor space and safety. She described herself as being “very safe when I do it, I’m very safe” because she always made sure to select an outdoor space to do sex work- often a parking lot. Similarly, Mitch said: “Yeah, to be honest I’d rather do it in a car. It’s more easier if something does go wrong.” These insights differed from other studies where outdoor sex work, that which takes place in cars specifically, is highlighted as posing the greatest risks to women’s safety (Shannon et al. Citation2009).

Working in private spaces selected by clients and doing overnight dates were more lucrative financially compared to the ‘basic’ thirty to sixty-minute encounter, but they were also described as dangerous situations that many women sought to avoid. Several participants linked safety concerns with the murder of several sex workers in Kitchener-Waterloo (four in the year 2013 alone). For Steffanie, this meant hiding the fact that she was homeless, which clients could interpret as signs of severe socio-economic and/or familial deprivation and use to justify entrapment, kidnapping, or worse. As she said: “it helps when you’re planning if they think you are not at a shelter…and it’s my rule now. I don’t go to anybody’s house due to safety issues. Like after that woman was cut up and killed.” Evelyn expressed similar fears associated with meeting at the client’s place: “I was always too afraid to meet anyone at their house because I didn’t want anybody to chop me up and kill me…So I would have them come to my house, right, where I’d feel safe.”

Places to avoid

As shows, the locations participants wanted to avoid are very similar to the places where they experienced violence. They cited the same number of locales for both queries. The spaces/places that surfaced here without being specified as violent include: near the Police Station; Cameron Parking Lot; Madison St.; the Google Building; Church St. and Peter St. The areas the women wanted to avoid fall directly within and appeared to be engulfed by the spaces associated with violence, and these overlapping spatialised settings constituted a rather antagonistic area within downtown Kitchener-Waterloo. It is also important to note that participants’ discussions about avoidance mainly concerned their movements at night and mainly, but not exclusively, in relation to sex work-related experiences.

Alleyways were among the most frequently discussed spaces the women seek to avoid. The fear such spaces evoked was palpable in the interviews: “All the alleys. I would never go through the alleys, okay. Never there, no, never in the alleys. Never, never…They are pretty scary” (Thea). Hall’s Lane was marked out as a particularly frightening place. Regina explained that her desire to avoid it was linked with pre-existing anxieties about the dark: “I won’t go near that one [Hall’s Lane]. I won’t go there. I just don’t like going in dark places. I don’t even sleep in the dark. I have to have lights on and the TV going because I’m scared.” In her colourful account of these alleyways, Baya included some interesting information about how she and others in the local street culture are perceived by ‘square’ outsiders or yuppies:

Never back streets, never, never, never. And absolutely never King Street, ever, ever, ever…Too many people gawking. Too many people that are bound to call the cops on you. Too many yuppies running up and down the street back and forth from Tim Hortons to their office job. They don’t know what you’re going through in life and they think they’re being a good citizen and patting themselves on the back.

Additional downtown areas participants sought to avoid include King Street, a main artery for seemingly every aspect of the lives of the women in our study. Freya linked this main thoroughfare with drinking and the prospect of violence: “Okay worst- King… There is a lot of drinking on the street, there is bars on the street… Drinking is hand-in-hand with violence…that's where I stayed away from.” Another place participants mentioned frequently was Weber Street: “I stay clear of Weber Street right in the core…. There are a couple of buildings that are a little too ghetto” (Laurie). Taylor indicated that it was not just the street but the kinds of men who hang out there that she wanted to avoid: “Certain areas on Weber, because that is usually where a lot of the unsanitary males would be, the ones that do needles and stuff, that are a little more, you know, rude and forceful.” The Cedar Hills area surfaced repeatedly in the women’s narratives: “I usually try to not go to Cedar Hills, anywhere near it. I would go up and around it and never through it. I would stay away from like this area here it's pretty bad” (Nina). Participants cited The Soup Kitchen and several adjacent businesses that are part of Kitchener’s ‘Tech block’ as additional places to avoid: “The Soup Kitchen, so it’s like this little block. It’s like The Tannery and the Google building” (Steffanie). More than one participant indicated that the whole downtown core should ideally be avoided. This is impossible for most women but reflected their pervasive fear of this area: “I should just circle everywhere” (Pamela).

Discussion

This paper has explored how street-based sex workers in Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario think about and navigate their socio-spatial experiences related to service provision, violence and places they avoid to protect themselves from danger or stigmatising encounters. Our data support the findings of other North American researchers who have examined space as a determinant of health and power among women in sex work. These allied findings include the need for decentralised, multi-service access points (Dewey and St. Germain Citation2016; Knight Citation2015), the ubiquity of violence in sex workers’ daily routines and spatialised networks (Draus, Roddy, and Asabigi Citation2015; McNeil et al. Citation2014; Lowman Citation2000; Orchard et al., Citation2016), a desire to access certain services regarding sex work and drug use in more discreet locales (Kim et al. Citation2014), and the socio-spatial convergence related to service provision and violence (Bourgois and Schonberg Citation2009; Fast et al. Citation2010). Our study results also contribute new insights into the ways in which women in street-based settings conceive of space and use spatialised terms to express their social location and resist stigma associated with sex work and drug use, thus extending our knowledge about the relationship between space, health, stigma, subjectivity and power in important ways.

A central finding of our research is that sex workers in Kitchener-Waterloo want to avoid the spaces they find to be violent but, paradoxically, these areas were those where most social and health services are located. Other studies have shown how gentrification and techniques of socio-political surveillance amplify sex workers’ spatial ghettoisation and compromise their physical safety and ability to access services (Hail-Jares, Shdaimah and Leon Citation2017; Dewey and St. Germain Citation2016; Katsulis Citation2008). However, unlike those settings where workers were typically pushed out into more marginal urban spaces (Deering et al. Citation2014; McNeil et al. Citation2014; Shannon et al. Citation2008), participants in our study remained in the centralised spaces they sought to avoid because services are located there, it is their primary working environment, and there are fewer places to move or escape to in a smaller city like Kitchener-Waterloo (see Fast et al. Citation2010). These ten to fifteen blocks in the downtown core are contested places and their navigation is a critical aspect of the women’s working and non-working lived experiences. This is illustrated in the different spatial practices women adopt to mitigate violence during encounters with clients, which include not walking in certain downtown areas, only working in open spaces (i.e. parking lots, cars), and not going to places selected by potential clients. It was also seen with The Soup Kitchen, the most utilised service agency that is identified as a place of violence that many women seek to avoid.

Participants also discussed the need for additional health services downtown, where many such services are already located within the social service setting. This finding suggests that a more comprehensive landscape of provision might increase health service use. However, the uptake of embedded health services is dependent upon clear and targeted messaging, something currently lacking in the study site. Thus, it is not just the existence of services that matters but rather the kind of services, where they are located, and how they align with the way the target population uses them (Goldenberg et al. 2017; Johnson et al. Citation2004). A unique finding in this regard was the importance of communicating about these issues in ways that reflect how the women think about health, which is primarily biomedical in nature and distinct from their conception of social services. As with other studies, participants also identified the lack of affordable transportation as a systemic barrier to their health management (Barker et al. Citation2015; Kim et al. Citation2014). Having access to free or reduced bus fare would create choices for women to blend health-seeking practices in peripheral cityscapes that offer protection and anonymity with those in accessible central areas where they primarily work and live.

Some participants advocated for decentralised locales for services associated with sex work and drug use, which reveals a complex relationship between health, space, stigma, and service provision (Benoit, McCarthy and Jansson Citation2015; McCarthy, Benoit and Jansson Citation2014). Navigating these competing forces requires spatialised agency, which women used to restructure the moral geography that directs their movements and how they are perceived by others. Preference for accessing stigmatised services away from the downtown core where they spend most of their time reflects the desire to maintain a sense of propriety and safety, while managing certain aspects of their health in a less visible manner. The ways that socio-legal techniques of governance dictate where and how sex workers move through urban spaces is well-documented (Boels and Verhage Citation2016; Deering et al. Citation2014; Hubbard, Matthews and Scoular Citation2008; Kunkel Citation2017). However, our discussion of the relationship between space, health services, and propriety contributes new data concerning the spatial strategies women use to mitigate the stigma associated with sex work, drug use and street-culture more generally. It also fleshes out the women’s emic constructions of space, which is another key contribution the paper makes to the sex work and geography literatures.

The repeated use of the term “everywhere” by participants during the social mapping activities reflects important insights about how sex workers in Kitchener-Waterloo conceptualise different aspects of their lives in relation to broader socio-political and civic structures. In one sense everywhere exemplifies what Lefebvre (Citation1991) calls perceived space, referring to concrete, objective physical space. It signifies the need to restructure service facilities and address the spatialised dangers this group of women experience regularly. However, everywhere also emerges as a kind of conceived space (Lefebvre Citation1991) that is socially constructed and draws upon spatial representations that the women employ to express their relative powerlessness vis-à-vis the civic and social bodies in charge of administrating services safely. Do participants really want more services everywhere and what might this crowded provision landscape look like? Would having services everywhere alleviate women’s concerns about privacy, stigma and being afraid of certain places in the city, in the light of the finding that violence and attendant avoidance practices also occur everywhere? Although not a primary study theme, a sufficient number of women use the term everywhere in this wholesale manner, signalling a need for us to consider its more figurative meanings. Exploring how women use this term as a vehicle of expression also aligns with calls from leading social geographers for more politicised analyses of space in sex work mapping research:

Locating sex work districts within wider urban contexts accordingly involves more than simply ‘mapping’ their occurrence; it requires an exploration of how their manifestation reflects, and reproduces, dominant social and spatial orders (Hubbard Citation2016, 314).

Representations of powerlessness cannot be understood in isolation from their political context and in this research setting the women’s lives are socially and spatially circumscribed in multiple ways, as borne out in our data. Study participants do not always receive empathetic and effective services, they work and live in urban spaces that are often dangerous to their health and safety, and they discussed feeling frustrated with the stereotypical ways they are represented in the media (i.e. as “drug-dependent sex workers” instead of as women with lives that matter). Considered against the backdrop of women’s lives, everywhere is not an exaggerated request for more services or an idyllic civic environment free of all harms. This mode of expression is rather a means though which they register their disdain for present circumstances, highlight the inadequacy of existing service structure and delivery and assert their social value, which is expressed in spatial terms. Women’s use of the term everywhere loudly critiques current configurations of risk and power. Unpacking this term enables us to think more deeply about the spatiality of women’s social lives (Gotham Citation2003) as well as the spatialised nature of their subjectivity and agency (Orchard and Dewey Citation2016).

The women in our study asked to be acknowledged. Our project is one of the few opportunities they have had to express what their daily lives are like and to advocate, albeit in small ways, for changes in the urban landscape they called home. These findings enrich our understanding of spatialised conceptions of health, stigma and agency, as well as subjectivity among women in street-based sex work. They also reveal participants’ emic perspectives about their compromised socio-economic position and how their broader civic participation, or lack thereof, is inexorably linked with the social relations that produce urban spaces and render them meaningful. Asking to be acknowledged and provided services with dignity is an assertion of agency and it demonstrates the degree to which space as a concrete and socially constructed representation is used in the navigation of their subjectivities as women in sex work, as service recipients, and as citizens with rightful ‘claims to the city’ (Purcell Citation2002, 103).

Our findings inform the international sex work and social geography literatures and they make a particularly important contribution to the Canadian sex work canon. As a large, ethnically diverse nation characterised by distinctive cultures and uneven economic development, there are regional and city-wide differences among women (and others) in sex work that are important to examine. This is especially true for those involved in street-based sex work in smaller cities, whose experiences have been largely overshadowed by those of sex workers based in larger metropolitan areas. This is due to the preponderance of researchers, greater numbers of sex workers, and the enhanced availability of academic and allied socio-economic supports required to facilitate such research in metropolitan centres. Shedding light on the experiences of women in smaller areas is also central to destabilising centrist notions in certain academic and social circles that the experiences of people in large urban centres are of more significance than those of individuals living in places further afield. Women in sex work everywhere, not just those in the large cities, are engaged in daily struggles to survive and negotiate competing forces of risk and resilience with those of health, survival and dignity.

Acknowledgements

A heartfelt thank you to participants, who shared their lives with us and who share with us the desire to make a difference in how people who engage in sex work are treated and thought about in the spaces they call home. We also thank the Canadian Institutes of Health Research for funding this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Bus passes are expensive (CA$86 per month) and at $3.25 a one-way ticket is also beyond the means of many women.

References

- Aral, S., J. St. Lawrence, and A. Uusküla. 2006. “Sex Work in Tallinn, Estonia: The Sociospatial Penetration of Sex Work into Society.” Sexually Transmitted Infections 8: 348–353.

- Barker, B., T. Kerr, P. Nguyen, E. Wood, and K. De Beck. 2015. “Barriers to Health and Social Services for Street-Involved Youth in a Canadian setting.” Journal of Public Health Policy 36 (3): 350–363.

- Benoit, C., B. McCarthy, and M. Jansson. 2015. “Stigma, Sex Work, and Substance Use: A Comparative Analysis.” Sociology of Health & Illness 37 (3): 437–451.

- Boels, D., and A. Verhage. 2016. “Prostitution in the Neighbourhood: Impact on Residents and Implications for Municipal Regulation.” International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice (46): 43–56.

- Bourgois, P., and J. Schonberg. 2009. Righteous Dopefiend. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101.

- Brock, D. 2009. Making Work, Making Trouble. The Social Regulation of Sexual Labour. 2nd ed. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

- Collins, A., S. Parashar, K. Closson, R. Turje, C. Strike, and R. McNeil. 2016. “Navigating Identity, Territorial Stigma, and HIV Care Services in Vancouver, Canada: A Qualitative Study.” Health & Place 40: 169–177.

- Deering, K., M. Rusch, O. Amram, J. Chettiar, P. Nguyen, C. Feng, and K. Shannon. 2014. “Piloting a ‘Spatial Isolation’ Index: The Built Environment and Sexual and Drug Use Risks to Sex Workers.” International Journal of Drug Policy 25 (3): 533–542.

- Dewey, S., and T. St. Germain. 2016. Women of the Street: How the Criminal Justice-Social Services Alliance Fails Women in Prostitution. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Draus, P., J. Roddy, and K. Asabigi. 2015. “Making Sense of the Transition from the Detroit Streets to Drug Treatment.” Qualitative Health Research 25 (2): 228–240.

- Fast, D., J. Shoveller, K. Shannon, and T. Kerr. 2010. “Safety and Danger in Downtown Vancouver: Understandings of Place Among Young People Entrenched in an Urban Drug Scene.” Health & Place 16: 51–60.

- Ferris, S. 2015. Street Sex Work and Canadian Cities: Resisting a Dangerous Order. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press.

- Goldenberg, S., K. Deering, O. Amram, S. Guillemi, P. Nguyen, J. Montaner, and K. Shannon. 2017. “Community Mapping of Sex Work Criminalization and Violence: Impacts on HIV Treatment Interruptions Among Marginalized Women Living with HIV in Vancouver, Canada.” International Journal of STD & AIDS 28 (10): 1001–1009.

- Gotham, K. 2003. “Toward an Understanding of the Spatiality of Urban Poverty: The Urban Poor as Spatial Actors.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27 (3): 723–737.

- Hail-Jares, K., C. Shdaimah, and C. Leon, eds. 2017. Challenging Perspectives on Street-Based Sex Work. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Hubbard, P. 2001. “Sex Zones: Intimacy, Citizenship and Public Space.” Sexualities 4 (1): 51–71.

- Hubbard, P. 2016. “Sex Work, Urban Governance and The Gendering of the City”, In The Routledge Research Companion to Geographies of Sex and Sexualities, edited by G. Brown and K. Browne, 313–320. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Hubbard, P., R. Matthews, and J. Scoular. 2008. “Regulating Sex Work in the EU: Prostitute Women and the New Spaces of Exclusion.” Journal of Feminist Geography 15 (2): 137–152.

- Johnson, J., L. Bottorff, A. Browne, S. Grewal, A. Hilton, and H. Clarke. 2004. “Othering and Being Othered in the Context of Health Care Services.” Health Communication 16 (2): 255–271.

- Kaiser, B., E. Haroz, B. Kohrt, P. Bolton, J. Bass, and D. Hinton. 2015. “‘Thinking too much’: A Systematic Review of a Common Idiom of Distress.” Social Science & Medicine 147: 170–183.

- Katsulis, Y. 2008. Sex Work and the City: The Social Geography of Health and Safety in Tijuana, Mexico. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

- Kim, S., S. Goldenberg, P. Duff, P. Nguyen, K. Gibson, and K. Shannon. 2014. “Uptake of a Women-Only, Sex-Work-Specific Drop-in Center and Links with Sexual and Reproductive Health Care for Sex Workers.” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 128 (3): 201–205.

- Knight, K. 2015. Addicted.pregnant.poor. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Kunkel, J. 2017. “Gentrification and the Flexibilization of Spatial Control: Policing Sex Work in Germany.” Urban Studies 54 (3): 730–746.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Blackwell: Oxford.

- Lowman, J. 2000. “Violence and Outlaw Status of Street Prostitution in Canada.” Violence Against Women 6 (9): 987–1011.

- Macdonald, J. 2017. “Downtown Gentrification Study: Why Urban Change Matters to All of Us.” Posted on The Hive-Waterloo Region. Accessed 2 September 2017. http://hivewr.ca/2017/07/24/gentrification-study/

- Mathieu, L. 2011. “Neighbors’ Anxieties Against Prostitutes’ Fears: Ambivalence and Repression in the Policing of Street Prostitution in France.” Emotion, Space and Society 4: 113–120.

- McCarthy, B., C. Benoit, and M. Jansson. 2014. “Sex Work: A Comparative Study.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 43: 1379–1390.

- McDowell, L. 1999. Gender, Identity and Place: Understanding Feminist Geographies. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- McNeil, R., K. Shannon, L. Shaver, T. Kerr, and W. Small. 2014. “Negotiating Place and Gendered Violence in Canada’s Largest Open Drug Scene.” International Journal of Drug Policy 25: 608–613.

- Orchard, T., and S. Dewey. 2016. “How Do You Like Me Now?: The Spatialization of Research Subjectivities and Fieldwork Boundaries in Research with Women in Sex Work.” Anthropologica 58 (2): 250–263.

- Orchard, T., J. Vale, S. Macphail, C. Wender, and T. Oiamo. 2016. “’You Just Have to Be Smart’”: Spatial Practices and Subjectivity among Women in Sex Work.” Gender, Place & Culture 26 (11): 1572–1585.

- Parent, C., C. Bruckert, P. Corriveau, M. Mensah, and L. Toupin. 2013. Sex Work: Rethinking the Job, Respecting the Workers. Translated by Kathe Roth. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Pitcher, J., R. Campbell, P. Hubbard, M. O’Neill, and J. Scoular. 2006. Living and Working in Areas of Street Sex Work: From Conflict to Coexistence. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Purcell, M. 2002. “Excavating Lefebvre: The Right to the City and Its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant.” GeoJournal 58: 99–108.

- Scheper-Hughes, N. and M. Lock. 1987. “The Mindful Body: A Prolegemenon to Future Work in Medical Anthropology.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1 (1): 6–41.

- Shannon, K., T. Kerr, S. Strathdee, J. Shoveller, J. Montaner, and M. Tyndall. 2009. “Prevalence and Structural Correlates of Gender-Based Violence Among a Prospective Cohort of Female Sex Workers.” BMJ 339: b2939. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2939

- Shannon, K., M. Rusch, J. Schoveller, D. Alexson, K. Gibson, and M. Tyndall. 2008. “Mapping Violence and Policing as an Environmental-Structural Barrier to Health Service and Syringe Availability among Substance-Using Women in Street-Level Sex Work.” International Journal of Drug Policy 19: 140–147.

- Sharp, J. 2009. “Geography and Gender: What belongs to feminist geography? Emotion, Power and Change.” Progress in Human Geography 33 (1): 74–80.

- Statistics Canada. 2013. Dissemination Areas, X CMA, 20Nina Census (cartographic boundary file). ArcGIS Edition. Accessed September 25, 2017. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/20Nina/geo/bound-limit/bound-limit-2011-eng.cfm

- Statistics Canada. 2015. 20Nina Census. Road Network File. ArcGIS Edition. Accessed 25 September 2017. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2011/geo/RNF-FRR/index-eng.cfm

- van der Meulen, E., E. Durisin, and V. Love, eds. 2013. Selling Sex: Experience Advocacy, and Research on Sex Work in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Weitzer, R., and D. Boels. 2015. “Ghent’s Red-Light District in Comparative Perspective.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy 12: 248–260.

- Wright, M. 2010. “Gender and Geography II: Bridging the Gap-Feminist, Queer, and the Geographical Imaginary.” Progress in Human Geography 34 (1): 56–66.