Abstract

Globally, female sex workers bear a disproportionate burden of HIV, with those in sub-Saharan Africa being among the most affected. Community empowerment approaches have proven successful at preventing HIV among this population. These approaches facilitate a process whereby sex workers take collective ownership over programmes to address the barriers they face in accessing their health and human rights. Limited applications of such approaches have been documented in Africa. We describe the community empowerment process among female sex workers in Iringa, Tanzania, in the context of a randomised controlled trial of a community empowerment-based model of combination HIV prevention. We conducted 24 in-depth interviews with participants from the intervention community and 12 key informant interviews with HIV care providers, police, venue managers, community advisory board members and research staff. Content analysis was employed, and salient themes were extracted. Findings reveal that the community empowerment process was facilitated by the meaningful engagement of sex workers in programme development, encouraging sex worker ownership over the programme, providing opportunities for solidarity and capacity building, and forming partnerships with key stakeholders. Through this process, sex workers mobilised their collective agency to access their health and human rights including HIV prevention, care and treatment.

Introduction

Female sex workers are disproportionately affected by HIV globally (Baral et al. Citation2012). Community empowerment approaches for HIV prevention have proven successful in addressing social and structural determinants of HIV such as stigma, discrimination and violence and reducing HIV risk among sex workers (Kerrigan et al. Citation2015; Kerrigan et al. Citation2013). These approaches have also shown promise in improving HIV care and treatment outcomes in this key population (Kerrigan et al. Citation2016). Community empowerment approaches have been recognised as a UNAIDS Best Practice for almost two decades (Jenkins Citation2000) and remain the recommended approach for HIV prevention among sex workers by global health and development agencies (World Health Organization et al. 2013, 2012).

Informed by empowerment theory, community empowerment approaches seek to achieve social and economic inclusion by enhancing individual and collective agency to alter power relations (Kabeer 1999; Sen Citation1990; Blankenship et al. Citation2006). In this process, sex workers take collective ownership over programmes and services and work together to address the social and structural sources of their HIV vulnerability (Blanchard et al. Citation2013; Campbell Citation2000; Cornish, Shukla, and Banerji Citation2010; Cornish and Ghosh Citation2007; Kabeer 1999; Sen Citation1990). These approaches recognise sex work as work, including the right to safe work environments and access to HIV services.

Given the high levels of stigma, discrimination, and violence experienced by sex workers (Human Rights Watch Citation2013), a sense of internal social cohesion is critical in initiating the community empowerment process. This involves providing opportunities for sex workers to come together to form a collective identity and strong social bonds characterised by trust and reciprocity (Bourdieu Citation1986; Swartz Citation1997). By leveraging their internal cohesion and forming partnerships with key stakeholders, sex workers may act to promote their social participation including political decision-making forums that affect their health and well-being. They may also work to promote their social inclusion or access to material resources, such as income generating opportunities or health and social services (Hawe and Shiell Citation2000; Bourdieu Citation1986).

Drawing on this theoretical foundation, United Nations agencies and the Global Network of Sex Work Projects published the Sex Worker Implementation Tool (SWIT) in 2013 to provide guidance on the development of community empowerment programmes for HIV prevention among sex workers (World Health Organization et al. 2013). The SWIT highlights the importance of adopting a human-rights approach and encouraging the meaningful participation of sex workers in programme development. It notes the need for programmes to provide opportunities for solidarity and capacity building to facilitate collective action and leadership. It also highlights the importance of programme flexibility and forming strategic partnerships with stakeholders to create an enabling environment.

Although there is increasing evidence on the effectiveness of community empowerment approaches for HIV prevention among female sex workers, most of this research has been conducted in South Asia (Basu et al. Citation2004; Reza-Paul et al. Citation2008), Latin America (Lippman et al. Citation2012; Kerrigan et al. Citation2008), and the Caribbean (Kerrigan et al. Citation2016) with limited research in sub-Saharan Africa (Kerrigan et al. Citation2015; Kerrigan et al. Citation2013). A systematic review of community empowerment approaches to HIV prevention for female sex workers found no rigorous evaluations of such approaches in Africa (Kerrigan et al. Citation2013), despite the fact that female sex workers in this region have the highest burden of HIV globally (Shannon et al. Citation2018). Other research has documented sexual and reproductive health interventions using empowerment approaches among sex workers in Africa (Moore et al. Citation2014), and grassroots mobilisation efforts among sex workers to address HIV (Global Network of Sex Work Projects Citation2015; Mgbako Citation2016).

In response to these gaps in the literature, our team1 conducted a randomised trial of a community empowerment model of combination HIV prevention, Project Shikamana (Kiswahili for ‘Let’s Stick Together’), among female sex workers in Iringa, Tanzania (Kerrigan et al. Citation2017). The trial documented a significant difference in incident HIV infections between the intervention and the control community at 18-month follow-up, and significant differences in multiple behavioural outcomes along the HIV care continuum (Kerrigan et al. Citation2019). We conducted a qualitative sub-study including in-depth interviews (IDI) with participants in the intervention community and key informant interviews (KII) with local stakeholders to understand the community empowerment process that took place during this trial. Here, we document how a successful community empowerment approach was stimulated and operationalised in this African context, using the framework outlined by the SWIT.

Methods

Setting

This study took place in Iringa, Tanzania. Iringa is bifurcated by the Tanzanian-Zambian Highway, which brings truck drivers and migrant workers through the region, increasing the demand for sex work (Research to Prevention Citation2013). Although sex work is criminalised in Tanzania (Government of the United Republic of Tanzania Citation1981), as it is in many African countries, it is widely tolerated (Beckham Citation2013). Many sex workers seek clients in venues such as bars, where some sex workers are employed as bar maids (Beckham Citation2013).

Study overview

Project Shikamana was a community randomised controlled trial of a community empowerment-based combination HIV prevention intervention for female sex workers. Two communities were matched on demographic and HIV risk characteristics and randomised to receive the intervention or control, which was the local standard of care. Venue-based time location sampling was used to enrol a cohort of 203 HIV-infected and 293 HIV-uninfected female sex workers (total of 496 cohort members). Eligible participants were tested for HIV (with viral load assessment as relevant) and completed a baseline and 18-month follow-up survey. The main trial outcomes were HIV acquisition for those HIV-uninfected and viral suppression (<400 copies/mL) for those HIV-infected at baseline. A detailed description of the study has been published elsewhere (Kerrigan et al. Citation2017). Findings on violence and financial security have also been published (Leddy et al. Citation2018; Mantsios et al. Citation2018) and are examined here in the context of the qualitative sub-study to understand the empowerment process that took place. The intervention elements described below were first offered in October 2015 and supported by the project through December 2017.

Intervention description

Project Shikamana emerged in response to findings from formative research conducted by our team, including in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with sex workers, which revealed high levels of sex work-related stigma, discrimination and violence, and women’s desire for greater financial security to reduce their HIV risk (Research to Prevention Citation2013). This work also found that sex workers in Iringa had already naturally formed informal networks and savings groups to address issues that were important to them (Research to Prevention Citation2013). Women expressed interest in building upon these existing networks and mobilising their community to achieve their mutual goals. The project took a rights-based approach and sought to promote and protect sex workers’ right to work, access quality health care, and violence-free lives.

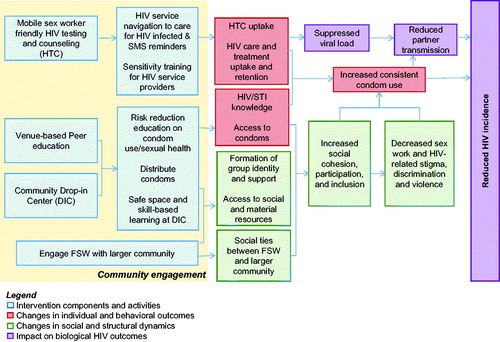

depicts the intervention model generated from this formative research. It outlines the intervention components and activities implemented, as well as the social and behaviour change processes that were stimulated by these elements including reductions in stigma, discrimination and violence through the generation of social cohesion, participation and inclusion. Shifts in these socio-structural dynamics were hypothesised to lead to improvements in health behaviours (e.g. consistent condom use and engagement in HIV care and treatment) and in turn reductions in HIV incidence and greater viral suppression.

Of critical importance were early and ongoing efforts to form relationships with local government health officials. These relationships were formed through regular meetings between the local study team and regional government health officials. Study leadership described the burden of HIV among female sex workers in the region and the need for programmes to protect their health and prevent onward HIV transmission to garner support and partnership.

Project Shikamana consisted of a set of community-driven, multi-level intervention components that sought to address HIV prevention and engagement in HIV care and treatment. The intervention reflected the principles of community empowerment interventions and the results from formative work. A community advisory board, composed of female sex workers from Iringa, provided input on each intervention component, designed to meet the needs sex workers identified in the formative work. The community advisory board raised awareness about the study within the community and participated in the randomisation process. During the study, the sex worker community further shaped the intervention, determining the specific intervention activities and services offered, and leading efforts to improve their financial security and safety (described below). Intervention components included: (1) a community-led Drop-in-Center, a safe place where women came together to mobilise around challenges to their health and human rights; (2) venue-based peer education, condom distribution and HIV testing and counselling; (3) Peer service navigation for prevention, care and treatment, and SMS reminders to promote ART adherence; and (4) sensitivity training for HIV clinical care providers and police around the unique health and safety needs of sex workers.

Project Shikamana was facilitated by a number of different actors including the local sex worker community, the community advisory board, an advisory board (including government health officials, police representatives, and HIV providers), peer navigators and educators (referred to here as peer navigators), and local intervention staff. Peer navigators were identified by community advisory board members as women with leadership capacity and were hired as project staff and trained in peer education and HIV service navigation. They conducted health education sessions, led workshops and trainings at the Drop-in-Center, and participated in sensitivity training with HIV providers and police. They also provided personalised support to HIV-infected and uninfected women in their caseload. They helped HIV-infected women navigate the health care system and stay engaged in HIV care and treatment and supported HIV-uninfected women to engage in HIV prevention behaviours including consistent condom use.

Sampling and recruitment

We conducted 24 semi-structured IDIs with individuals who participated in intervention components and 12 KIIs with members of the intervention staff (3), peer navigators (2), community advisory board members (2), an HIV provider (1), managers of venues where sex work is known to occur (2) and police (2). Key informants were sampled purposively to include individuals engaged in the Project Shikamana intervention, and from sectors where there were challenges with engagement and partnership.

Baseline data and tracking information were used to purposively sample 24 participants from the intervention cohort based on the following characteristics to facilitate analytic comparisons and ensure variation in the sample: laboratory confirmed HIV status (12 HIV-infected and 12 HIV-uninfected) and level of engagement in the intervention (12 high engagement and 12 low engagement). Participants who were living with HIV and those who were HIV negative were recruited to allow for exploration of different experiences with and perceptions of the intervention.

Participants were also stratified by level of participation in the intervention to understand factors that facilitated and prevented intervention engagement. Intervention engagement was evaluated by number of Drop-in-Center workshops attended and whether or not peer navigation services were accepted because these were the key intervention components hypothesised to facilitate community empowerment. High engagement in the intervention was defined as accepting peer navigation services and attending at least two Drop-in-Center workshops. Participants were contacted by phone and asked if they were interested in participating in this sub-study. All women were assigned pseudonyms to protect confidentiality.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted between August 2016 and August 2018 in a private location and lasted between 45 and 60 minutes. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The 24 IDIs were conducted in Kiswahili by two female interviewers. The three KIIs with intervention staff were conducted in English by the first author, while the remaining KIIs were conducted in Kiswahili by the local research team.

Interviews were conducted using semi-structured interview guides. The IDI guide consisted of broad, open-ended questions to explore women’s thoughts and perspectives on their experience participating in the intervention, including key community empowerment domains (i.e., social cohesion, social inclusion), their perception of intervention strengths and weaknesses and recommendations.

The interview guide for the KIIs consisted of open-ended questions that explored key informants’ perspectives on and experiences with the intervention and its components, including successes and challenges, as well as suggestions for project improvement and expansion.

Data analysis

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, the IDIs and KIIs conducted in Kiswahili were translated into English, and all interviews were uploaded into Atlas.ti (Proprietary Software Citation2016) for coding. Data were analysed using an inductive-deductive thematic analysis approach (Pope, Ziebland, and Mays Citation2000; Green and Thorogood Citation2006). Analysis was facilitated through multiple readings of the transcripts and memo writing to highlight emergent themes and insights. An initial coding schema was developed based on a priori codes, informed by key domains covered in the interview guides and empowerment theory. The coding schema was iteratively revised by adding new codes for additional themes that emerged.

The codes were systematically applied across all transcripts, using memos to elaborate upon the codes and their application. Data were organised hierarchically into table format, with a table for each major theme, sub-themes listed beneath the major themes, and summaries of different perspectives and experiences from several participants. This method allowed data to be compared and contrasted across different themes (horizontal analysis), and within each case (vertical analysis), to provide explanations for the findings (Green and Thorogood Citation2006).

This study received human subjects research approval from the Institutional Review Boards of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, and the National Institute for Medical Research of Tanzania. Participants received the equivalent of USD 2.50 for participation.

Findings

The following sections highlight how Project Shikamana facilitated the development of solidarity among female sex workers in Iringa, and how women subsequently mobilised to impact outside institutions and began to realise their priorities. We also reflect on challenges faced and ways to strengthen future efforts.

The initial approach of project Shikamana: rights, respect and meaningful participation

In line with the SWIT, one of the first actions taken during Project Shikamana was the establishment of a safe space, the Drop-in-Center, for sex workers in the intervention community to come together and discuss issues that affected them. Participants viewed the Drop-in-Center as a place where they could openly be ‘working women’ (the term they used to refer to themselves), share their stories and concerns, and be treated with respect and dignity, which was not how they were typically treated in other spaces.

It is beneficial when you have a problem and there is a place you can go to report and be heard. And not that you go to report and they say, ‘this is a prostitute’ … when there is a place to be heard when we get problems, like [Project Shikamana], it gives heart when they consider us as human beings. (Esther, 28 years)

Project Shikamana emphasised the importance of sex worker collective ownership by ensuring that activities were shaped and defined by women’s needs and priorities. Based on findings from the aforementioned formative research, and continued discussion with the community, a series of workshops and trainings were offered at the Drop-in-Center on issues relevant to and determined by women, including stigma and discrimination, sex worker human and labour rights, violence prevention, financial security and business development, HIV/STI prevention, reproductive health and family planning. Peer navigators were trained to conduct these sessions in a manner that facilitated open and respectful discussion amongst participants, and the workshops provided opportunities to collectively develop strategies to overcome challenges and identify additional topics for future workshops. The meaning and importance of this community-led process of defining the key components of the intervention is exemplified here:

When there are things discussed in the [Drop-in-Center workshops], I like that the [project staff] listen to us and lead us to where we want to go.…We thank you because you heard us, understood us, and led us where we wanted to go. (Grace, 25 years)

Between October 2015 and December 2018, 75-125 sex workers visited the Drop-in-Center weekly to take advantage of services such as HIV testing, condom distribution and programming and social support.

Laying the groundwork for collective action: establishing connections and building solidarity

Through these meetings, sex workers began to recognise that they shared many common experiences and started to identify with each other. They began to build solidarity around their shared identity as ‘working women’. This shared identity was described as a unifying force that allowed them to come together to address the issues they all faced.

[Project Shikamana] has been really good … because if we sit with our fellow working women, we can sit, discuss things together, and even form our own groups. We had time to be together in unity with our fellow working women and talk about something that can bring us benefits. (Peer navigator)

Starting from this sense of solidarity, women began to identify ways they could help each other.

I feel good now because we stay together and advise each other. If someone has a problem, we help her. But in the past, there was no such thing. You might get sick and you wouldn’t get any help. But now, honestly, we women stick together. If you find your fellow is sick in any way, you will take her to the hospital and get her treatment. (Neema, 32 years)

As solidarity grew within the community, women were empowered to unify around the prices for services with clients in an effort to improve condom use:

When we are working…let us unite. If it is money, let us decide on [an] amount that each one of us knows, [so] when [you] go out with this one, he will pay this much… So, when you mention that amount, and I go and mention the same amount, they will fail to play around with us. (Peer navigator)

In addition to opportunities to meet as a group at the Drop-in-Center, the bonds between sex workers were also facilitated by the peer navigators. Through their work, peer navigators developed strong relationships with women in the community and provided an example of how sex workers can support and motivate each other. Below, Joyce describes how patient peer support encouraged her to access HIV care and treatment.

In December, I was in denial [about my HIV status]. I didn’t feel like accepting this status at all. I remember the day I got my results, I was so down. [My peer navigator] said ‘you just take your time and calm your mind then come back when you are ready so that we can discuss how to help you.’ But I stayed for the whole of December…every time I remembered that I have HIV, I cried. I thought my end had come. But [my peer navigator] used to call me [and say] ‘don’t lose hope.’ She used to encourage me until I got up with my own two feet [and] I said, ‘let us meet in town.’ After January… that is when [my peer navigator] took me directly to [the health clinic]. I am thankful they received me well. I was given priority, I was attended on time…I am good, I am still using medication well. [Project Shikamana] has helped me. (Joyce, 29 years)

While Project Shikamana successfully facilitated the initial process of connecting and solidarity-building among sex workers in the intervention community, the process was not without challenges. Interviews with key informants highlighted how the process of solidarity building among sex workers takes time and requires dialogue as challenges arise. They described how at the beginning, peer navigators struggled with disagreements about clients and distribution of work. In response, the project implemented regular weekly check-ins for peer navigators where they were encouraged to discuss disagreements amongst themselves, taking turns to facilitate and resolve issues.

Another challenge was the strained relationship between some of the community advisory board members and the peer navigators. As might be expected in a limited-resource setting, some women became upset that peer navigators received a salary for their role in the project, which included venue-based outreach, managing a caseload, facilitating Drop-in-Center workshops and other activities. Some community advisory board members felt that peer navigators received too much money. Project Shikamana staff addressed this issue directly with community advisory board members and peer navigators, explaining in detail the responsibilities and workload of the peer navigators, which made other women feel more comfortable with the compensation received.

[The community advisory board members and peer navigators] were arguing a lot. In the beginning I don’t think they understood how the peer navigators worked and why they were getting a salary. They didn’t have the wider knowledge of the workload that the peer navigators have really. So, we had to explain like ‘there is this and this and this that they are doing. That is why they are getting this money.’ (Project coordinator)

Putting a community-led framework into action: ownership, leadership and sustainability

As solidarity grew, women began discussing how they could jointly address the needs of their community through collective activities and mobilisation around issues such as financial security, violence prevention and healthcare access.

Financial security

Women requested training in entrepreneurship and business management to improve their financial security. Project Shikamana partnered with a local non-governmental organisation to provide training on business development and management. Women established a community savings group to which they contributed money to save for their business. Community advisory board members and peer navigators who participated in existing savings groups held a workshop on lessons learned from their experiences to inform the development and sustainability of the Project Shikamana savings group. The group began with 25 members and elected leaders including a chairwoman, secretary, treasurer and security guard. The leaders collected money and gave loans which accrued interest, generating additional funds. As the money was saved and circulated through loans, the group decided to establish a catering business.

To formalise its activities, the sex worker-led group registered with the government as an official business. The women used the money from the savings group to purchase supplies and rent a space for their business. The savings group gained popularity as other women witnessed its success, growing to 50 female sex workers. The savings group and the catering business became completely self-sustained and continued meeting and operating after the trial’s end.

Participants described how improved financial stability allowed women to better negotiate sex with clients. Prior to Project Shikamana, women were more willing to have unprotected sex for extra money. However, with more financial stability, women were able to demand condom use regardless of the higher offer.

It is true [women involved in Shikamana] have changed to a big extent. Now [female sex workers] don’t [agree to unprotected sex] as it was in the beginning. When a man would come and you talk to him, then you [would] agree [to unprotected sex] because you needed money. But now they do small businesses of selling maandazi, others are selling clothes. Everyone is hustling however much they can. So, that temptation of going with a man without any agreements [to use a condom] or without money, isn’t there. (Community advisory board member)

Violence prevention

Women in the intervention community also drew on their collective resources and power to prevent and respond to violence. After learning about their right to a violence free life and the laws and procedures related to redress for gender-based violence in Tanzania, women from the project took action. They created a working group where they met once a week to share stories of experiences with violence and strategise ways to collectively prevent and respond to violence. The group remained intact after the trial ended, continuing to hold weekly meetings with a core of 10 members.

Some strategies the group devised include exchanging cell phone numbers and agreeing to alert colleagues to violence. Some women also tell their colleagues when they are leaving the venue with a client, so their colleagues know where to find them if they are in danger. Women have also adopted the strategy of carrying whistles to alert their colleagues to violence.

A friend of ours, a fellow [sex worker], agreed to have sex with a customer. After getting inside [the room], she found two customers [and feared being gang raped]. Because she was already educated [by Project Shikamana], she blew her whistle. After she blew the whistle, some women went to her. After knowing what had happened, we were all called through phones. After being called, we all came to the room, and the customer ran. Because she knew him, we went with her and reported it to the police station, so it was followed up…If he comes back, they will arrest him. (Linda, 23 years)

Participants revealed that they rarely report violence to the police due to fear, or experiences, of additional human rights abuses such as being made to have sex with an officer or pay a bribe for the police to investigate their case. In response, Project Shikamana held a sensitivity training event with police officers. Project Shikamana drew on relationships with government officials, including the local police chief, to conduct a training event. During the event, peer navigators shared challenges of women’s experiences trying to access justice for violence. Participants noted that this helped to increase sex workers’ reports of violence to the police.

Many [female sex workers] now understand the right place to [report gender-based violence]. Meaning that… ‘when I suffer gender-based violence, I have to go to the police’… She comes [and says] ‘this and this has been done to me, can you please give me a PF3 [form] (needed to access treatment for injuries and document forensic evidence to take legal action) so that I can go and get tested and get treatment and then I will come later to open a case?’ You know that she got this information from somewhere… and for now, there is only one project – the Shikamana project. (Police Officer)

Health care

The project also formed partnerships with HIV providers to address the barriers sex workers face in accessing health care. During formative work, women revealed that stigma and discrimination by HIV providers was a significant barrier to engagement in HIV care and treatment (Research to Prevention Citation2013). To address these barriers, Project Shikamana drew upon strong relationships with government officials, including the district health official, to conduct sensitivity trainings with HIV providers. Trainings were shaped by stories of women’s challenges accessing health care and stressed the human rights of sex workers, including their right to quality health care. They also emphasised the importance of treating sex workers in a non-judgemental manner. Crucially, the sensitivity training provided a space in which providers could acknowledge, critically examine, and challenge their attitudes about sex workers.

Peer navigators attended the end of each provider training, once providers were sensitised and ready to hear what the women had to say, to strategise how to collaborate to overcome the challenges sex workers face in accessing health care.

In the beginning [providers] were negative about sex worker issues. But we kept going and I think the most important thing was bringing the peers [into the trainings] and they were able to speak out for others. It was easy for the peers to challenge the [providers] and explain things in front of them. In the beginning, the [providers] had a negative attitude towards the peers, but in the end, it was really different. (Project coordinator)

The positive influence Project Shikamana had on providers’ attitudes towards female sex workers and providers’ willingness to prioritise sex workers’ health is further reflected in the following quote.

If it were not for [Project Shikamana] we would not have recognised [sex workers]. It is possible that we would have known about them, but not value them. So, the project has helped those women. We have recognised them, and they have also felt that they are also people in the society…The relationship has become good because of the project. There was no good relationship before…It was like a group that is somehow stigmatised. It was to the extent that when [a sex worker] came, she was harassed. She was treated so harshly such that she failed to get the appropriate service. But after the project, there has been a good relationship. (HIV provider)

Over time, these trainings went beyond sensitisation to include the formation of a substantial partnership between HIV providers and peer navigators to identify and collaboratively implement solutions to the main challenges sex workers faced in adhering to treatment and clinic visits.

Discussion

Findings from this study document the early stages of the community empowerment process among female sex workers involved in a community-driven combination HIV prevention intervention that had a significant impact on HIV incidence and care continuum outcomes in Iringa, Tanzania (Kerrigan et al. Citation2019). Community empowerment is a long, multi-stage process. This study provides evidence of the early stages of that process occurring in the context of, and being sustained beyond, an intervention trial. Findings reflect the salience of the key elements of the community empowerment framework outlined by the SWIT, including encouraging the meaningful participation of sex workers, providing opportunities for solidarity and capacity building among sex workers, and forming partnerships with key stakeholders (World Health Organization et al. 2013) such as government officials. Importantly, this study is the first to describe the community empowerment process as applied to the implementation of a combination HIV prevention among female sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa.

Findings highlight the importance of adopting a human and labour rights framework and stimulating the leadership of sex workers as a way to build trust between the sex worker community and researchers and facilitate sex worker ownership over the programme. By emphasising sex workers’ labour and human rights, treating them with dignity and respect, and giving them the space to take ownership over and drive the direction of the project, Project Shikamana was better able to meet needs and ultimately facilitated the project’s impact and sustainability as evidenced by the continued efforts of the sex worker-led working groups and business.

Furthermore, conducting formative work among sex workers in Iringa enabled Project Shikamana to design a programme that was responsive to community priorities. For example, formative work found that sex workers in Iringa had already naturally formed informal networks and savings groups to address financial and safety concerns (Research to Prevention Citation2013) suggesting that women were in the beginning stages of a community empowerment process, demonstrating the potential for the success and sustainability of a community empowerment approach to combination HIV prevention. Project Shikamana sought to build on these existing models to facilitate the community empowerment process. Future community empowerment approaches among sex workers may also benefit from trying to identify communities that are already beginning to mobilise informally so that efforts are understood as ‘of the community.’

Our findings highlight the critical role that establishing a Drop-in-Center played in solidarity building and setting the stage for collective action and community mobilisation. The Drop-in-Center offered a space for women to congregate to share challenges and problem solve. Sex workers began to form a collective identity and social cohesion that enabled them to mobilise their resources to advocate for their priorities such as improving their financial security, preventing violence and accessing health care. Prior community empowerment approaches for HIV prevention among sex workers in South East Asia and Latin American and the Caribbean have documented a similar process of community building and mobilisation through the use of Drop-in-Centers (Laga et al. Citation2010; Kerrigan et al. Citation2016). Findings build on this past work and demonstrate that a similar social process can be stimulated in sub-Saharan Africa.

Our findings also support the importance of forming partnerships with key stakeholders such as government officials, police officers and HIV providers to overcome structural barriers sex workers face in accessing their health and human rights. Engaging government stakeholders from the beginning to build relationships and support for the overall development, implementation and evaluation of the project in partnership with the sex worker community was a critical piece of this process. Given that sex work is criminalised in Tanzania, as it is in many African countries, this strategy helped ensure the safety and sustainability of the project. However, it is important to note that Tanzania’s socialist history, and its emphasis on communalism (Ibhawoh and Dibua Citation2003), may have also shaped government officials’ willingness to collaborate with the project.

Finally, our results support prior research which has found that holding training with stakeholders such as health providers to sensitise them to the realities and needs of sex workers provides an important opportunity for stakeholders to acknowledge, critically examine, and challenge the attitudes they hold (Jana et al. Citation2004; Reza-Paul et al. Citation2012). Our results also suggest the importance of providing opportunities for sex workers to come together with providers to jointly address these issues. Findings revealed that over time the sensitisation training with HIV providers, in particular, resulted in concrete changes that improved sex workers’ access to HIV care and treatment. Although the project held only one sensitisation training event with the police during the study period, members of the police were responsive to the content covered in the training and indicated their willingness to work with the project in the future. Evidence from other community empowerment approaches to HIV prevention among female sex workers in other settings have demonstrated that sensitisation training with police can effectively improve women’s access to justice and human rights (Biradavolu et al. Citation2009), indicating the importance of incorporating such efforts in future implementation.

Limitations

Study limitations included only interviewing women who were engaged in the intervention and thus not capturing if the empowerment process reached sex workers outside of the intervention community. An additional limitation was not having the opportunity to conduct interviews at a later time point to assess the project’s longer-term impact and sustainability. It is also possible that participants may not have felt comfortable providing critical feedback in relation to the intervention. To reduce this potential limitation, interviewers were trained to establish rapport with participants before beginning all interviews to help them feel comfortable sharing their honest perspectives of the intervention.

Conclusion

Findings from this study document the essential elements of a community empowerment process among female sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa as they mobilised to challenge the social and structural factors that contribute to their disproportionate risk for HIV and sub-optimal care and treatment outcomes. Core components of the community empowerment process included the meaningful engagement of sex workers in programme development, encouraging sex worker ownership over the programme, providing opportunities for solidarity and capacity building, and forming partnerships with key stakeholders. This work provides support for the use of the SWIT but also underscores the importance of engaging government officials as partners from the onset of the process, particularly in settings where sex work is criminalised.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The Project Shikamana study team included: DK, JM, SL, NG, WD, CS, AM, SWB, AM and AL

References

- Baral, S., C. Beyrer, K. Muessig, T. Poteat, A. L. Wirtz, M. R. Decker, S. G. Sherman, and D. Kerrigan. 2012. “Burden of HIV among Female Sex Workers in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The Lancet Infectious Diseases 12 (7): 538–549.

- Basu, I., S. Jana, M. J. Rotheram-Borus, D. Swendeman, S. J. Lee, P. Newman, and R. Weiss. 2004. “HIV Prevention among Sex Workers in India.” Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 36 (3): 845–852.

- Beckham, S. 2013. “Like Any Other Woman”? Pregnancy, Motherhood, and HIV among Sex Workers in Southern Tanzania.” PhD diss., Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- Biradavolu, M. R., S. Burris, A. George, A. Jena, and K. M. Blankenship. 2009. “Can Sex Workers Regulate Police? Learning from an HIV Prevention Project for Sex Workers in Southern India.” Social Science & Medicine 68 (8): 1541–1547.

- Blanchard, A. K., H. L. Mohan, M. Shahmanesh, R. Prakash, S. Isac, B. M. Ramesh, P. Bhattacharjee, V. Gurnani, S. Moses, and J. F. Blanchard. 2013. “Community Mobilization, Empowerment and HIV Prevention among Female Sex Workers in South India.” BMC Public Health 13 (1): 234.

- Blankenship, K. M., S. R. Friedman, S. Dworkin, and J. E. Mantell. 2006. “Structural Interventions: Concepts, Challenges and Opportunities for Research.” Journal of Urban Health 83 (1): 59–72.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 46–58. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

- Campbell, C. 2000. “Selling Sex in the Time of AIDS: The Psycho-Social Context of Condom Use by Sex Workers on a Southern African Mine.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 50 (4): 479–494.

- Cornish, F., and R. Ghosh. 2007. “The Necessary Contradictions of 'Community-Led' Health Promotion: A Case Study of HIV Prevention in an Indian Red Light District.” Social Science & Medicine 64 (2): 496–507.

- Cornish, F., A. Shukla, and R. Banerji. 2010. “Persuading, Protesting and Exchanging Favours: Strategies Used by Indian Sex Workers to Win Local Support for Their HIV Prevention Programmes.” AIDS Care 22 (sup2): 1670–1678.

- Global Network of Sex Work Projects. 2015. “SWIT Case Study.” Accessed April 11, 2019. https://www.nswp.org/resource/swit-case-study

- Government of the United Republic of Tanzania. 1981. “Tanzania Penal Code Chapter 16 of the Laws (Revised) (Principal Legislation).” http://www.lrct.go.tz/

- Green, J., and N. Thorogood. 2006. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Hawe, P., and A. Shiell. 2000. “Social Capital and Health Promotion: A Review.” Social Science & Medicine 51 (6): 871–885. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00067-8

- Human Rights Watch. 2013. “Treat us like Human Beings”: Discrimination against Sex Workers, Sexual and Gender Minorities, and People Who Use Drugs in Tanzania.” Washington D.C., USA: Human Rights Watch.

- Ibhawoh, B., and J. I. Dibua. 2003. “Deconstructing Ujamaa: The Legacy of Julius Nyerere in the Quest for Social and Economic Development in Africa.” African Journal of Political Science 8 (1): 59–83.

- Jana, S., I. Basu, M. J. Rotheram-Borus, and P. A. Newman. 2004. “The Sonagachi Project: A Sustainable Community Intervention Program.” AIDS Education and Prevention 16: 405–414.

- Jenkins, C. 2000. “Female Sex Worker HIV Prevention Projects: Lessons Learnt from Papua New Guinea.” India, and Bangladesh.” Geneva: UNAIDS.

- Kabeer, N. 1999. “Resources, Agency, Achievements: Reflections on the Measurement of Women's Empowerment.” In Development and Change, edited by Institute of Social Studies, 435–464. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Kerrigan, D., C. Barrington, Y. Donastorg, M. Perez, and N. Galai. 2016. “Abriendo Puertas: Feasibility and Effectiveness a Multi-Level Intervention to Improve HIV Outcomes among Female Sex Workers Living with HIV in the Dominican Republic.” AIDS & Behavior 20 (9): 1919–1927.

- Kerrigan, D., C. E. Kennedy, R. Morgan-Thomas, S. Reza-Paul, P. Mwangi, K. Thi Win, A. McFall, V. A. Fonner, and J. Butler. 2015. “A Community Empowerment Approach to the HIV Response among Sex Workers: Effectiveness, Challenges, and Considerations for Implementation and Scale-up.” The Lancet 385 (9963): 172–185.

- Kerrigan, D. L., V. A. Fonner, S. Stromdahl, and C. E. Kennedy. 2013. “Community Empowerment among Female Sex Workers Is an Effective HIV Prevention Intervention: A Systematic Review of the Peer-Reviewed Evidence from Low- and Middle-Income Countries.” AIDS & Behavior 17 (6): 1926–1940.

- Kerrigan, D., J. Mbwambo, S. Likindikoki, S. Beckham, A. Mwampashi, C. Shembilu, A. Mantsios, A. Leddy, W. Davis, and N. Galai. 2017. “Project Shikamana: Baseline Findings from a Community Empowerment-Based Combination HIV Trial of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes.” Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 74 (1): S60–S68.

- Kerrigan, D., J. Mbwambo, S. Likindikoki, W. Davis, A. Mantsios, S. W. Beckham, A. Leddy, C. Shembilu, A. Mwampashi, S. Aboud, et al. 2019. “Project Shikamana: Community Empowerment-Based Combination HIV Prevention Significantly Impacts HIV Incidence and Care Continuum Outcomes among Female Sex Workers in Iringa, Tanzania.” Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes.

- Kerrigan, D., P. Telles, H. Torres, C. Overs, and C. Castle. 2008. “Community Development and HIV/STI-Related Vulnerability among Female Sex Workers in Rio De Janeiro, Brazil.” Health Education Research 23 (1): 137–145.

- Laga, M., C. Galavotti, S. Sundaramon, and R. Moodie. 2010. “The Importance of Sex-Worker Interventions: The Case of Avahan in India.” Sexually Transmitted Infections 86 (Suppl 1): i6– i.7.

- Leddy, A. M., C. Underwood, M. R. Decker, J. Mbwambo, S. Likindikoki, N. Galai, and D. Kerrigan. 2018. “Adapting the Risk Environment Framework to Understand Substance Use, Gender-Based Violence, and HIV Risk Behaviors among Female Sex Workers in Tanzania.” AIDS & Behavior 22 (10): 3296–3306.

- Lippman, S. A., M. Chinaglia, A. A. Donini, J. Diaz, A. Reingold, and D. L. Kerrigan. 2012. “Findings from Encontros: A Multilevel STI/HIV Intervention to Increase Condom Use, Reduce STI, and Change the Social Environment among Sex Workers in Brazil.” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 39 (3): 209–216.

- Mantsios, A., N. Galai, J. Mbwambo, S. Likindikoki, C. Shembilu, A. Mwampashi, S. W. Beckham, A. Leddy, W. Davis, S. Sherman, et al. 2018. “Community Savings Groups, Financial Security, and HIV Risk among Female Sex Workers in Iringa, Tanzania.” AIDS & Behavior 22 (11): 3742–3750.

- Mgbako, C. A. 2016. To Live Freely in this World: Sex Worker Activism in Africa. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Moore, L., M. F. Chersich, R. Steen, S. Reza-Paul, A. Dhana, B. Vuylsteke, Y. Lafort, and F. Scorgie. 2014. “Community Empowerment and Involvement of Female Sex Workers in Targeted Sexual and Reproductive Health Interventions in Africa: A Systematic Review.” Globalization and Health 10 (1): 47.

- Pope, C., S. Ziebland, and N. Mays. 2000. “Qualitative Research in Health care. Analysing qualitative data.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 320 (7227): 114–116.

- Proprietary Software. 2016. “Atlas.ti.”

- Research to Prevention. 2013. “Strategic Assessment to Define a Comprehensive Response to HIV in Iringa, Tanzania Research Brief: Female Sex Workers.” USAID. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/research-to-prevention/publications/iringa/Iringa-FSW-brief-final.pdf

- Reza-Paul, S., T. Beattie, H. U. R. Syed, K. T. Venukumar, M. S. Venugopal, M. P. Fathima, H. R. Raghavendra, P. Akram, R. Manjula, M. Lakshmi, et al. 2008. “Declines in Risk Behaviour and Sexually Transmitted Infection Prevalence following a Community-Led HIV Preventive Intervention among Female Sex Workers in Mysore, India.” AIDS 22 (Suppl 5): S91–S100.

- Reza-Paul, S., N. O′Brien, J. Jain, P. F. Mary, K. N. Raviprakash, R. Steen, R. Lorway, L. Lazarus, M. Bhagya, K. T. Venukumar, et al. 2012. “Sex Worker-Led Structural Interventions in India: A Case Study on Addressing Violence in HIV Prevention through the Ashodaya Samithi Collective in Mysore.” The Indian Journal of Medical Research 135 (1): 98–106.

- Sen, A. 1990. “Gender Equality and Cooperative Conflicts.” In Persistent Inequalities: Women and World Development, 123–149. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Shannon, K., A. L. Crago, S. D. Baral, L. G. Bekker, D. Kerrigan, M. R. Decker, T. Poteat, A. L. Wirtz, B. Weir, M. C. Boily, et al. 2018. “The Global Response and Unmet Actions for HIV and Sex Workers.” Lancet 392 (10148): 698–710.

- Swartz, D. 1997. Culture and Power: The Sociology of Pierre Bourdieu. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Global Network of Sex Work Projects, and The World Bank. 2012. “Prevention and Treatment of HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Infections for Sex Workers in Low-and Middle-Income Countries: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach.” Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization, United Nations Population Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, Global Network of Sex Work Projects, and The World Bank. 2013. Implementing Comprehensive HIV/STI Programmes with Sex Workers: Practical Approaches from Collaborative Interventions. Geneva: World Health Organization.