Abstract

A person diagnosed with HIV today might never experience AIDS, nor transmit HIV. Advances in treatment effectiveness and coverage has made the UN 2030 vision for the ‘end of AIDS’ thinkable. Yet drug adherence and resistance are continuing challenges, contributing to avoidable deaths in high burden African countries, especially among men. The mood of global policy rhetoric is hopeful, though cautious. The mood of people living with HIV struggling to adhere to life-saving medication is harder to capture, but vital to understand. This paper draws on ethnographic fieldwork with a high burden population in Kenya to explore specific socio-economic contexts that lead to a potent mixture of fatalism and ambition among men now in their thirties who came of age during the devastating 1990s AIDS crisis. It seeks to understand why some HIV-positive members of this bio-generation find it hard to take their life-saving medication consistently, gambling with their lives and the lives of others in pursuit of a life that counts. It argues that mood – here understood as a shared generational consciousness and collective affect created by experiencing specific historical moments – should be taken seriously as legitimate evidence in HIV programming decisions.

Introduction

Omondi and Atomic1

‘HIV has really changed’, Omondi, a hustler in his thirties living in Kisumu City, Kenya, wrote to me in 2014. ‘Back in the early 1990s it was perceived as a curse in the backwaters where I was born. My first understanding of HIV/AIDS was grim and foggy. Tales of local men of repute in diapers and the huge cost of medication that left even well-off families in poverty before the death of breadwinners was hard to imagine for 14 year old me. As the number of orphans soared, we called it ‘the life gobbler that clears all’. If you had AIDS, yours was only death. But now young people call that medicine [anti-retroviral therapy] andila - meaning it is just like swallowing kernels of corn.’

A few months after Omondi wrote passionately about changes in everyday experiences of HIV, he found himself in the city morgue. He had come to collect the body of his cousin Atomic, a lively computer-repairs freelancer, for the long drive to Atomic’s final resting place high on a hill overlooking the Great Lake and the small homes, maize farms and many graves of their relatives. Over the last five years Atomic’s life had oscillated between periods of crisis and fantastic effort towards big dreams and energetic entrepreneurial hustling. At one point he became the repair man for most of the city’s internet cafes; the next he was arrested for participating in a scheme to illegally resell national telecommunications connections. He moved house often, depending on his fortunes. He trained to become a Pentecostal pastor and developed a heavy alcohol addiction. He married, and acrimoniously separated. His mood was unpredictable.

Atomic’s eulogy, composed by Omondi, read:

Born in 1980, Atomic flourished, healthy and aggressive […] But after surviving bouts of depression mid-2013, Atomic’s life took a worrying turn. So did his hope, career and health. Several times Atomic tried unsuccessfully to pull himself up. Sometimes he would commit himself to prayer… He tried so hard to play his role as father, husband, brother, contractor and neighbour. He really tried. In the early hours of the 29th December, Atomic succumbed to TB. Atomic had his high roads and low moments. Some will praise him, others will vilify him.

In this setting a death like Atomic’s at the age of 36 is not a surprise to friends and family, mourned with sadness tempered by resignation and the refrain ‘not again. We are tired.’ Such quietened anguish is most achingly captured in the words of Atomic’s younger male relative, Bro:

Uwwwwii…the earth does not get full. Death never tires or takes a break. Death has no sympathy for youth. How long, people of our home, since we buried? Are we, the youth, not to achieve anything in life?

Atomic’s unnecessary, avoidable death, hurried along by alcohol, despair and not taking his life-saving and, by that time, widely and freely available once-a-day anti-retroviral therapy [ART] serves as a poignant reminder that even now AIDS remains, as a common refrain in East African school songs stresses, ‘a killer disease’.

This paper uses the stories of Atomic and others, gathered during ethnographic fieldwork in Western Kenya between 2008 and 2012 and followed to date, to highlight the importance of unravelling the social, economic and historical contexts of a generational mood, or affect, that influences the life-choices and chances of HIV-positive men. It offers insights as to why men like Atomic struggle to continue living with HIV despite living with the disease at the most promising time in its history. I consider the shaping of life chances beyond conventional risk factors, bringing into view both individual biographies, collective histories and wider socio-economic structures.

AIDS after ART

Atomic, Omondi and their peers were living with HIV at a time where universal treatment access has, largely, been successful. People can describe anti-retroviral drugs as corn kernels because they have access to free medication in a single tablet formulation with lowered initiation criterion and reduced journey times to clinics that were unimaginable a decade ago. Yet, there is compelling evidence that maintaining the rates of diagnosis, treatment and, crucially, suppression of viral load required to keep HIV a manageable, non-transmittable condition remains challenging. Analysis of mortuary-based HIV surveillance data in Nairobi shows that although 73.6% of adults living with HIV are on treatment, which should be leading to a palpable decrease in mortality, their risk of death is still more than four times higher than those uninfected (Young et al. Citation2017). This is somewhat unexpected given that ART has been shown to dramatically increase life-expectancy in lower-income countries (Nsanzimana et al. Citation2015). An inference can be drawn that some clients may be struggling with taking medication consistently. Another study in Kenya indicates that the rapid scale-up of treatment since 2010 is being undermined by high rates of treatment failure, with poor adherence a key factor (Ochieng-Ooko et al. Citation2010).

Men as a blind spot

HIV-positive men are particularly at risk of AIDS-related death and treatment interruptions (Ochieng-Ooko et al. Citation2010; Dovel et al. Citation2015). Reducing prevalence among young women has been the focus of global policy (UNAIDS Citation2014), with male mortality described as an ‘HIV blind spot’ (Shand et al. Citation2014). The two, of course, are intimately linked. The stories of HIV-positive men who struggle with adherence are also indirectly stories about younger women’s increased HIV risk, especially in contexts where intergenerational relationships, domestic and sexual violence are accepted cultural norms (Gust et al. Citation2017). Often studies have argued that certain constructions of masculinity are a barrier to men’s adherence and testing (Bwambale et al. Citation2008; DiCarlo et al. Citation2014), although it has been suggested that such explanations implicitly blame men and side-line more sophisticated structural explanations (Dovel et al. Citation2015).

Beyond blame and individualised risk factors

It can also be difficult to write about such things without, as has been argued, reducing complex lives to generic ‘barriers to adherence’ or individualised, decontextualised risk factors (Owczarzak Citation2009). Most work on risk has focused specifically on sets of discrete, sometimes correlated, behaviours. Here, I am interested more in the common thread that lies behind such actions - especially when seen over the course of a life - what has been described as ‘affect’ (Gregg and Seigworth Citation2010). Studies of affect explore the intuitive, hard to articulate forces or feelings beneath conscious knowing and actions. They move beyond ideas of individual emotions to think about how feelings are generated in dialogue with the world (Stewart Citation2007; Rutherford Citation2016). Within the HIV literature there has been some focus on feeling with discussions of the importance of hope and hopelessness (Bernays, Rhodes, and Barnett Citation2007; Kylmä, Vehviläinen-Julkunen, and Lähdevirta Citation2001). The causal links between poor adherence and hope is posited such that certain environments do not engender hope or long-term planning which, in turn, weakens self and community regulation of risk (Bernays and Rhodes Citation2009). But hope itself as a concept has been left relatively uninterrogated; considered simply as ‘a positive expectation of the future’ (Bernays, Rhodes, and Barnett Citation2007). For example, the study of barriers to adherence above listed ‘hopelessness’ and ‘bad feeling’ as reasons clients gave for non-adherence (Ochieng et al. Citation2015). What does this actually mean? There is a dearth of narrative between such descriptors that make it hard to extrapolate into meaningful policy action.

Furthermore, the feelings expounded in the stories of Atomic and others that I have followed over time resist simplistic bounded concepts like hope and hopelessness. Atomic could be both cheerful and ambitious, as well as driven to such pits of despair that he carried a rope to the fields thinking of hanging himself. And, although he did not envision himself living to see old age, he never stopped - in economic terms at least - planning for the future. A close examination of the specific socio-economic context can help understand such seemingly contradictory oscillating affects, and the correspondingly impact on his life chances.

In taking such an approach I am following anthropologists who have explored the social conditions of complex collective feelings or moods. For example, Scheper-Hughes unravelled the historical production of indifference to child death amongst mothers in a Brazilian shanty town, an indifference born out of social, economic and cultural logic, but one which contributed to the premature deaths of babies viewed as born ‘wanting to die’ (Scheper-Hughes Citation1993).

Anthropologists have also paid attention to collective mood among people living with HIV (Halkitis Citation2014; Morris Citation2008; Sagar Citation2013; Reynolds Whyte Citation2014). Writing about youth in pre-ART South Africa at the turn of the millennium, Morris (Citation2008) reported a collective, inflationary assumption of imminent catastrophe; namely, that everyone will die. She asked about the effect of this inflation on ‘the capacity of those who believe such statistics to orient themselves toward a future horizon’ (201), noting that economic deprivation and employment concerns were equally, if not more, pressing, and that this assumption of catastrophe was expressed not as panic, but as rush – with risk ‘now utterly internalised as the nature of life in the new South Africa’ (229).

In contrast, Reynolds Whyte (Citation2014) wrote movingly about the ‘second chance’ generation in Uganda. They draw on the work of Mannheim on the formative of generations to look at how shared historical experiences, especially events occurring at the time of coming into adulthood, ‘magnetise’ consciousness and produce a specific generational consciousness, representing a break in behaviour, feeling and thought to past generations (Mannheim Citation1952). They focus on the experiences of those people who contracted HIV before the global treatment scale-up, yet survived long enough to be initiated on ART. Describing this cohort as a ‘bio-generation’, whose consciousness was magnetised by the introduction of ART, they argue that the ‘experience of a second chance adds a dimension of intensity and reflection to many aspects of life’ (Reynolds Whyte Citation2014, 20). Such a consciousness or collective force provides this generation with a will to continue and to access treatment.

This is not necessarily the case, however, for the men aged 25–40 in Western Kenya in this ethnographic study. They experienced ART at a different time, and in a different social, political and economic context. Bringing together ideas of generational consciousness with affect theory, I now will explore the conditions that generate complex feelings among these HIV-positive men that make it hard for them to adhere to their medication. Like Reynolds Whtye (Citation2014), I trace historical events like the 1990s AIDS crisis and introduction of ART that have had a formative impact on this generation’s consciousness. I combine this with a consideration of their role models and ideas of what makes for a good life, notably the joy and promise of the successful entrepreneurial hustler. When this playful, energetic and fast lifestyle is situated against a far-reaching hangover of being part of the first post-AIDS generation in Kenya and an unshakeable feeling that their life expectancy will be curtailed, I argue this creates the context for an affect swinging between ambition, indifference and despair, and an accompanying lifetime trajectory of action oscillating between industrious and suspect. Rather than feeling ART is a second life chance, this generation’s collective heightened aspect of perception is the concept of (life) time as something experienced as always about to run out. Pinning down these feelings into one articulated emotion is difficult. Perhaps this is the reason that participants in the barriers to adherence to study mentioned above were only able to talk about ‘bad feeling’ (Ochieng et al. Citation2015). Here, the concept of affect is particularly useful as it describes feelings, moods or impulses beyond and beneath conscious thought and action (Gregg and Seigworth Citation2010). Ethnography involving following people’s everyday lives over time can help explicate the layered dimensions of collective affect.

Methodology

In 2008 I, a white British woman then in my late twenties, moved from the UK to Kisumu city, Western Kenya, to work on an anthropological study of the practices of a burgeoning HIV economy made up of HIV science and intervention workers, receivers of ‘intervention’ and others trying to make a living from flows of international funding into the area. Estimates of HIV prevalence ranged from 15% overall to 40% among men aged 30–34 years in one rural location in the province (Amornkul et al. Citation2009). Ethnographic fieldwork involved observation, conversations, individual and group interviews, first focused on the networks emanating from a HIV transnational medical research clinic in Kisumu (2008–2010) (Aellah and Geissler Citation2016) and then continuing through doctoral research in Akinda2 (2010–12), one of the rural field-sites for the transnational medical research organisation which hosted the study. In Akinda, I lived with a host family, following everyday experiences including joining youth and self-help groups. I participated in the daily routines of rural life, as well as conducting in-depth interviews and focus group discussions.

In accordance with the requirements of the ethical review boards of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the organisations involved in the transnational medical research collaboration that hosted this study in Kenya, written informed consent was obtained for interviews and focus groups, and verbal consent for participant observation. Omondi, Bro, and members of the friendship gang to which Atomic belonged reviewed this paper, giving permission to write about his life and death.

Following life trajectories

I first met Omondi, Atomic, and others with similar stories in 2009 in Kisumu City. They had moved from their villages in their twenties to attend college. In 2009, six years before his death, Atomic was unmarried and cheerful. He soon made enough from his unregistered computer repairs business to improve his mother’s rural home and construct a small, smart bachelor hut.

When I moved to rural Akinda in 2010, I met and followed several counterparts to Atomic and his peers; men mostly in their thirties who had not (yet) moved away to the city. I joined a ‘self-empowerment’ youth group which started off well. All members directly linked economic success with HIV prevention and dreamed big, talking of multi-storied chicken coups, fantasy hotels and securing government tenders. But by 2012, like Atomic, the lives of several of these men had also taken a turn for the worse, with one member chased out of the village at night on suspicion of harbouring ‘bad people’, leaving behind his girlfriend and baby. The energetic group chair, who by then had five young children, was also gone, the group’s micro-finance loan with him.

In this paper I consider these rural and urban-based men as a cohort. They are from the same tribe, generation and region, and it is not uncommon to find rural-based youth spending periods of time in the city trying to ‘make it’, or for urban-based youth to return to their rural homes when things get tough. Doing ethnographic research over a longer period of time helped me follow their life trajectories through several cycles, observing changeable fortunes and, in the case of several of the young men, their early deaths.

Generational consciousness of AIDS

The men whose stories I draw upon here were aged 25–40 in 2011. Many were born when Kenya’s average life expectancy reached its highest peak in the 1980s. Unlike people born later, some could remember funerals as relatively rare, special events. But many were also less than twenty years old in 2001 when Kenya’s life expectancy started to plummet, and AIDS was a taboo, the word rarely spoken out loud (Geissler and Prince Citation2010). A cross-sectional study in 2003 found extremely high HIV prevalence in some of Western Kenya's villages, with around 40% among men in the generation above Atomic and Omondi’s (Amornkul et al. Citation2009). This generation would have been their role models: older brothers and uncles, as well as their teachers and respected businessmen, then aged 30–34 years. Omondi recalled the first moment AIDS became a reality for him:

I was walking at home in the bush and I saw my favourite teacher passing. By then I had finished school and was just at home, farming a bit and waiting to find what to do next. This teacher, I really admired him. He let us borrow his novels and we learnt about the world outside. He was always dressed so smart; he had these nice shirts from [the capital]. But that day he was so thin and slow. I nearly did not recognise him. He had soiled himself – that uncontrollable diarrhoea. I had heard of this scaring sickness, and of AIDS, by then, but I had not thought about in relation to me.

In 2006 the roll-out of PEPFAR in Western Kenya meant that ART was suddenly more widely and freely available, although with complicated regimes, severe side-effects and rationed to only the sickest in major centres (Brown Citation2015). By 2010/11, ART had become available in once -a-day, less toxic formulation, criteria for treatment initiation was relaxed, although still at much lower CD4 counts that in the Global North (Brown Citation2010; National AIDS/STI Control Program Citation2011). Life expectancy was back to pre-AIDS crisis levels.

These men, therefore, had the dubious honour of directly experiencing, at a formative time in their younger lives, the effects of the greatest dip and then recovery in life expectancy in their community’s history. This is a truly transformative shared experience. They lost parents, siblings, aunts, uncles, friends and role models to AIDS. They were now able to refer to taking HIV drugs as something as ordinary and easy (and, perhaps, as careless) as swallowing kernels of corn. But unlike teenagers born post-ART and the future ‘AIDS Free Generation’, they could not distance themselves from knowledge that death is still there and, in Bro’s words, ‘has no sympathy for youth.’

Post ART, although the notion that everybody with HIV will die is not anymore evidentially supported, a broader acceptance of the expectedness of early death persists and affects ideas about lifetime and a necessity for speed of transition through life stages. A hangover of doubt relating to the robustness of ART provision and the unreliability of donors and government continues and affects orientation towards a lifetime spent on ART. Such expectations are situated in a context where semi-legal hustler economic action is seen as the best chance of economic success for young people in an uncertain, neo-liberal economy. The idiom ‘Get Rich or Die Tryin' popular in the rap songs listened to by Atomic and his youthful friendship gang at the turn of the millennium takes on a particular salience against their earlier experiences of HIV diagnosis as inevitable death in the 1990s and a continuing background expectation of early death today.

Expectations of early death

Throughout my fieldwork, a striking theme was an expectation of early death affecting people regardless of HIV status. In 2014, a Kenyan newspaper article stated that residents of 3 counties, including Akinda and Kisumu, – which are not the poorest, or furthest from health facilities - can ‘expect to live a mere 40 years under today’s social, economic and health conditions, a staggering 16 years shorter than [the country’s] average of 56.6 years’ (Okewo and Mungai Citation2014). My interlocutors agreed with this statement. It supported an expectation that had already been frequently expressed: that life is likely to end by 40. In 2011, I had queried one father in Akinda about the literalness of this interpretation of demographic data: ‘40? But you are 39 now and healthy. So…next year you will die?’ ‘Well,’ he laughed ruefully, ‘that is our life expectancy.’

The article also quoted a professor who said the outcome of this expectation is a thought process of ‘let me capitalise on time; I never know when this disease will strike me.’ The potential impact on decision-making among men considered ‘youth’ is shown in a conversation I observed between Dave, a rural -based 35-year-old, who earned his living from co-ordinating a network of youth groups and his father, a retired teacher in his 60s. Talking about the difference between ‘youth today’ and ‘our fathers’, Dave’s father lamented that Dave and his peers lived in a hurry - they weren’t interested in adding to their homes and building wealth slowly but surely. Their philosophy of wanting everything at once was dangerous. Dave argued life today was different. Senior ‘fathers’ (at least those who had gone to school and got the chance of government employment) looked forward to retirement as a time of growth and a chance to do business. ‘Now’, Dave explained ‘not only do we not have the chance to get those jobs, we don’t have time. We must hustle in a rush. We are not looking to our 50s to do our things. We only have now.’

The chair of the Self-Empowerment Youth group reiterated these sentiments when I asked why he and his wife had 5 children in such quick succession. He explained he wanted to get that part of his life done quickly: ‘Now, I am finished with [that], I can do my things. I have plans.’ The chair’s need to rush through life stages brought friction with his parents when he wanted to build his permanent rural home before his older brother, breaking with custom, saying ‘I don’t have time to wait for him to organise himself.’ The tension led him to destroy his bachelor hut and move his family out of his father’s compound into a rental house. This was an unusual and economically problematic move as he found himself struggling to make rent each month. It also threatened the chance for his family to seek shelter in his bachelor hut should he meet an early death.

Doubt in drugs, donors and the state

Expectations of early death are intensified for people living with HIV in their thirties; by their memories of AIDS, the side effects of HIV drugs and doubts about the dependability of international donors and the government. Although Atomic and Omondi’s generation do, sometimes, see that HIV is now liveable on ART, they also have memories of dozens of people who have died, despite going to a clinic.

Some of their older relations were initiated on ART at sub-optimal times and on drugs with more serious side-effects, when initiation criteria and regime choices were behind the gold standard of the Global North. Their bodies and faces might now have significantly changed, and they might be on second or third-line treatment regimes. Furthermore, Efavirenz, one of the drugs used in the main first line treatment combination (TDF/STC/EFV) between 2010 and 2017 has a well-documented side-effect, especially in the first month, of ‘serious mental health problems’3 including ‘feeling sad or hopeless’, ‘not being able to tell the difference between what is real or unreal’ and ‘not trusting other people.’ Niehaus has collected narratives of ‘bizarre and frightening’ intense ART-induced dreams among South Africans in a context where dreams are seen as portentous (Niehaus Citation2018). More research is needed to demonstrate the impact of this side-effect on the ability of already frightened people to maintain adherence, especially when dipping in and out of drug-taking. But anecdotally some of HIV-positive research participants talked about how taking ART was too ‘heavy’ and needed to be taken at an optimum time before ending a day’s activity and sleeping to avoid a night that blurred nightmare and reality. This challenge is especially pertinent for those working at night, wanting to socialise, drink alcohol, or concerned about the night-time security of their homes, things more often associated with men.

This feared side-effect of Efavirenz was compounded by a more generalised doubt in the quality of drugs and the motivations of donors. Doubt was not expressed directly but manifested in conversations such as with a young man in Akinda telling me about a research study paying women to deliberately expose themselves to HIV, or with an HIV activist, working with - and supportive of - a transnational medical research station who nonetheless felt there must be a parallel secret military motivation for their involvement. People often expressed the idea that a cure for HIV already existed in the West or that a cure invented by a national scientist had been deliberately shut down to increase Africa’s dependency on its donors (Ankomah Citation1996). Concerns about the quality of HIV drugs and the national supply chain circulated, validated by newspaper stories and evidenced by research studies on the prevalence of fake drugs in-country, as well as corruption of global health funds scandals.

The pressure to feel grateful

As has been demonstrated in other contexts, the projectified nature of HIV care and treatment in countries dependant on donor involvement or where HIV treatment is rationed means that there can be a tendency for HIV-positive clients to be expected to be excellent, active patients and furthermore, to feel grateful for their salvation through medication (Bernays, Rhodes, and Janković Terźić Citation2010; Reynolds Whyte Citation2014; Nguyen et al. Citation2007).

Certainly, despair followed by heart-felt gratitude was the emotional experience of many HIV-positive pregnant women I interviewed. Less so for men. A requirement of being a good patient is patience. In 2010–11 the process of obtaining medication at HIV centres was arduous, with long queues and a need to carefully ‘do as you are told’ (Prince Citation2012). Those deemed not be taking their medication properly had to undergo ‘defaulter training’, the quantity of drugs released to them reduced until they were deemed responsible patients, requiring more frequent clinic visits. For those feeling a need to rush through life to hit goals like markers of financial success and respect before death, the degree of waiting and admonishment required to obtain drugs could feel insurmountable, with visits to the clinic a painful reminder that they had already ‘messed’ their lives. In the words of one participant: ‘It makes me feel like a child back in school.’

Despite reduction in HIV stigma and discrimination in recent years, people still talked about the felt experience of stigma – especially what has become known as ‘self-stigma’. Omondi, for example, would not share his status with his family despite his elder sister already having disclosed hers with no ill consequences. ‘I just can’t. They will think of me differently. I need to be the strong one for them.’

Get rich or die trying: the lure of the hustle

Against these expectations of an early death and lack of faith in HIV care and treatment, what is seen as a good life for men like Atomic? Earlier, I indicated that for men of Atomic’s generation, a hustler lifestyle was seen as both the most accessible and as the most aspirational. During my fieldwork, most men in both the city and surrounding rural areas, were not able to access formal employment, following a period of economic and infrastructural decline in the 1980s/1990s. Now, the major sources of employment were offered by the HIV economy: NGO and research activity which limited opportunity to the few (Aellah and Geissler Citation2016). The rest relied on informal entrepreneurial hustling activities like Atomic’s semi-legal telecommunications activities in the city, or combining subsistence farming and fishing with ‘squad’ motorcycle taxi services (occasional hire of motorbikes from owner-friends for single fares) in rural areas where opportunities for hustling were reduced (Aellah and Geissler Citation2016).

Hustlers, according to a self-proclaimed one ‘live by the streets and know the streets.’ They might resell products in different locations at inflated costs, provide transport services, rent out their electrical equipment or connect suppliers to customers – probably all at the same time. What they have in common is their ability to quickly change their activities and creatively adapt. Another hustler explained ‘doctors they know how to treat people, lawyers know the law. We don’t have any skills - except we know how to hustle. And you can hustle with anything if you have that heart.’ In the case of the Self-Empowerment Youth Group this included hustling micro-financing loan organisations, leading to the Chair’s quick departure from Akinda.

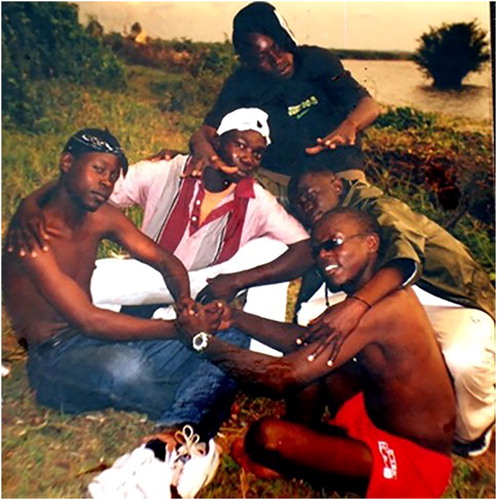

It is important to recognise that the hustle is more than an economic activity. It is lifestyle. It has a draw because of its joyful, creative energetic edge, as well as sinister capitalist drivers. above shows Atomic and Omondi with their youthful friendship gang – ‘the Starkuzzs’ – in 2002 when they were living at home by the lake, doing a bit of fishing and trying out ill-fated business schemes. They were waiting for a chance to be taken to college and dreaming of making it as hustler global rap-stars.

Their nickname was a play on ‘starkers’ (naked), and cousins (kuzz). They listened to Tu Pac and sang along to ‘Get Rich or Die Tryin’’. The picture was taken on the eve of the first free election since the country’s independence. Using pocket money gained by clerking for the election they had thrown themselves a party. In that moment, they felt unbwogable (unshakeable and indomitable), a hybrid word made popular by the song ‘Who Can Bwogo me? by musicians GidiGidi MajiMaji and adopted as the anthem of soon to be President Kibaki’s whose National Rainbow Coalition, supported by Luo opposition leader Raila Odinga, successfully challenged 24 years of de-facto single party rule. Although Starkuzz had witnessed many deaths from AIDS, none of them were – or knew they were – HIV-positive at this time. Their fathers suspected their dreams of hustling, rap and shady business would soon reshape through college and marriage and merely represented youthful rebellion. Shortly after this picture was taken Atomic was sponsored by an older sister to go to college in Kisumu city.

Five years after the Starkuzz posed together by the lake, following a tumultuous contested election at the end of 2007 and the violence and inflation that persisted into 2008, the StarKuzz’s rebellious global rap-star hustler role models began to crystallise in popular discourse into the figure of the ‘hustler’ as a more mainstream aspirational figure; an African entrepreneurial character associated with hard work, creativity and seizing opportunity, as well as shady dealings. The figure is placed in opposition to staid post-independence politicians with overseas education and impenetrable networks. The hustler as a ‘digital’ rather than ‘analogue’ caricature, with a resonance beyond East Africa (Di Nunzio Citation2012; Thieme Citation2013) offered a possible way to move forward in life when it seemed all others are blocked.

Post 2007, there have been many such hustler biographies to motivate the dreams of young men unable to access more traditional routes to success, not least vice-president Ruto, who markets himself as someone who came from ‘the village,’ as opposed to the president with his privilege and family political power. In 2013, the ‘rags to riches’ Ruto, then under suspicion at the International Criminal Court, declared himself the ultimate hustler. His ‘Hustler Jet’ grabbed a contract to transport politicians. Popular songs alternately praised the sweet VIP life of entrepreneurial hustlers and bemoaned the kigeugue or constant and unreliable ‘turn-about’ nature of people and circumstances in the current economic and political climate. Such popular self-proclaimed big hustler role-models like Ruto, Nairobi city governor Sonko, whose wealth is suspected to be amassed from illegal drugs, and musician Jaaguar, who later became an MP, and then was imprisoned, offer youth the promise of economic success and an aspirational, consumerist lifestyle that the route of formal education and formal employment cannot afford them. They also offer danger and slippage into illegality, as well as dramatic falls in fortune. Atomic’s ‘low road’ moment of illegal entrepreneurship is a demonstration of this.

The dangers of the hustle

The Self-Empowerment Group was also touched by the lure of hustler dreams. By forming a group, individuals could access micro-financing and generate capital to invest, something they would otherwise be denied. In 2013, I heard that the group’s chair had disappeared with some loan money. He had earlier confessed to me that he formed the group as part of a hustle - a way of accessing quick loans for several business schemes because he had no other avenues to generate investment capital. A combination of big dreams of successful hustling, a feeling of kigegeu (that people could never really be trusted) and a sense of a need to rush partially contributed to the collapse of activities. Youth who had started off with good-ish intentions started to cross the line between good and bad hustling. I was reminded of the experiences of Omondi, Atomic’s cousin, who had been part of a group specifically created to fight HIV after attending an HIV conference at church. They decided to grow immune-boosting vegetables to distribute freely to the needy, selling the surplus to a hospital. At first this ran well. Members farmed together and distributed money equally. But soon the group began to be offered more opportunities, including cement to build an office. Issues arose among members about who was accessing the benefits. Omondi, frustrated with being side-lined for some training events, oversaw accepting the cement. He had been saving the money from his part of the vegetable profits to buy a motorbike. His ultimate plan was to use the motorbike as a taxi to gain enough money to buy a car which he could then rent out to NGOs at a large profit. Together with another member he hatched a plan to ‘lose’ the cement but secretly sell it to a builder. With the profit he planned to buy his motorbike, reasoning this would quickly allow him to get enough money to replace the cement. But of course, the motorbike business proved slower and more precarious than in his dreams, the lost cement was never replaced, and he had to go into hiding. ‘I really believed I could do it,’ he told me wryly. ‘I had a positive attitude!’

The impact of hustling on ART adherence

These cycles of trying, collapse and trying again can have a seriously destabilising impact on the lives of those also struggling with their commitment to ART. Such oscillations in fortune create breaks in routine, often involving moving away from home for a time, which make it hard to continue consistently with HIV treatment and the commitment needed to ensure regular care at a clinic. They also damage relationships with wives and girlfriends which could otherwise have been supportive of treatment adherence. But, perhaps more importantly, they create highs and lows in fortunes leading to highs and lows in mood and producing periods of stress where motivation to continue with the everyday effort of routine treatment is threatened, as well as periods when the most important thing in life is the pursuit of a new hustle, rather than attention to health, which anyway might feel a little like a less important and lost cause.

Towards an anthropology of avoidable deaths

This paper offers an exploration of the social, economic and historical contexts that help generate a collective affect among the ‘bio-generation’ of Atomic and his peers. Memories of the devastation of the peak of the AIDS crisis, experienced as teenagers, and an expectation that even now life is likely to end at 40 is coupled with modern expectations of a fast-paced hustler life and tempered by doubts in previously trusted others like donors, governments, role models and friends.

Atomic and his friends live in a world where anything feels possible: a simple village hustler can become Vice-President and own a jet. But they also live in a world where this is not the experience for most. Experiencing the gap is painful. The affect, or force, unconsciously underlying their actions, could be described as the feeling of balancing on the edge of an abyss, below which lies alcohol, fatalism about the future, doubts in politicians, role models and international donors, as well nostalgia for the seemingly more predictable past of their elders, and the trauma and horrific deaths of the AIDS crisis experienced by their younger selves. It is not surprising that here some get lost and find it hard to believe in, and regularly take, their ‘andila.’ To describe this simply as ‘hopelessness’ does not give credit to the rich, complex depth of feeling involved. Capturing it requires writing in a way that evokes some of the flow and rhythm of life, what has been called ‘evocative ethnography’ (Skoggard and Waterston Citation2015).

It is important to take seriously complex emotions or socially and economically constructed moods, affects and bio-generational experiences into HIV policy decisions. It involves moving beyond a consideration of discrete risk factors to try to understand a common thread or impulse (here glossed as a mood or affect), that influences men’s responses to challenges and experiences over a lifetime.

There are recent innovations that offer potential for taking such things into consideration. Social network interventions perhaps offer as a way forward (Salmen et al. Citation2015). Based on a theory that ‘HIV infection too often falls solely and silently on the shoulders of infected individuals’ (Salmen et al. Citation2015, 333), there have been interventions that assume collective responsibility for care and create treatment management collectives of friends, neighbours and kin whose aim is to support the emotions of those struggling with treatment. It is also worth considering the positive effect that more actively promoting Undetectable Equals Untransmittable campaign messages could have for those who find it hard to believe that HIV is no longer death, giving them a feeling of more time to live lives compatible with good treatment adherence.

Acknowledgements

Grateful thanks to the project's institutional collaborators, especially the research staff, and the many others who gave up their time to talk to me or share their thoughts on this paper. I greatly acknowledge the contribution of the Starkuzz to the thinking that informed it, as well as my PhD supervisors. Acknowledgements to Lucy, Molly and Phili for their fieldwork expertise.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 People’s names, and some surrounding contextual information, have been changed to maintain a degree of anonymity/confidentiality in accordance with the research protocol, as approved by the ethics review boards of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the organisations involved in the transnational medical research collaboration that hosted this study in Kenya.

2 Akinda is a pseudonym used to maintain a degree of anonymity/confidentiality, in accordance with the research protocol, as approved by the ethics review boards of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and the organisations involved in the transnational medical research collaboration that hosted this study in Kenya.

3 www.aidsinfo.nih.gov (last accessed 28 September 2018).

References

- Aellah, G., and P. W. Geissler. 2016. “Seeking Exposure: Conversions of Scientific Knowledge in an African City.” The Journal of Modern African Studies 54 (3): 389–417. doi:10.1017/S0022278X16000240

- Amornkul, P. N., H. Vandenhoudt, P. Nasokho, F. Odhiambo, D. Mwaengo, A. Hightower, and A. Buvé. 2009. “HIV Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors among Individuals Aged 13-34 Years in Rural Western Kenya.” PLoS One 4 (7): e6470. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006470

- Ankomah, B. 1996. “AIDS – Why African Successes Are Scoffed.” New African 21 (344): 16–17.

- Bernays, S., and T. Rhodes. 2009. “Experiencing Uncertain HIV Treatment Delivery in a Transitional Setting.” AIDS Care 21 (3): 315–321. doi:10.1080/09540120802183495

- Bernays, S., T. Rhodes, and T. Barnett. 2007. “Hope: A New Way to Look at the HIV Epidemic.” AIDS 21 (Suppl 5): S5–S11. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000298097.64237.4b

- Bernays, S., T. Rhodes, and K. Janković Terźić. 2010. “You Should Be Grateful to Have Medicines”: Continued Dependence, Altering Stigma and the HIV Treatment Experience in Serbia.” AIDS Care 22 (sup1): 14–20. doi:10.1080/09540120903499220

- Brown, H. 2010. “Living with HIV/AIDS: An Ethnograpy of Care in Western Kenya.” PhD Diss., Manchester University.

- Brown, H. 2015. “Global Health Partnerships, Governance, and Sovereign Responsibility in Western Kenya.” American Ethnologist 42 (2): 340–355. doi:10.1111/amet.12134

- Bwambale, F. M., S. N. Ssali, S. Byaruhanga, J. N. Kalyango, and C. A. Karamagi. 2008. “Voluntary HIV Counselling and Testing among Men in Rural Western Uganda: Implications for HIV Prevention.” BMC Public Health 8 (1): 263. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-263

- Di Nunzio, M. 2012. “We Are Good at Surviving”: Street Hustling in Addis Ababa's Inner City.” Urban Forum 23 (4): 433–447. doi:10.1007/s12132-012-9156-y

- DiCarlo, A. L., J. E. Mantell, R. H. Remien, A. Zerbe, D. Morris, B. Pitt, E. J. Abrams, and W. M. El-Sadr. 2014. “Men Usually Say That HIV Testing Is for Women': Gender Dynamics and Perceptions of HIV Testing in Lesotho.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 16 (8): 867–882. doi:10.1080/13691058.2014.913812

- Dovel, K., S. Yeatman, S. Watkins, and M. Poulin. 2015. “Men's Heightened Risk of AIDS-Related Death: The Legacy of Gendered HIV Testing and Treatment Strategies.” AIDS 29 (10): 1123–1125. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000655

- Geissler, W., and R. Prince. 2010. The Land Is Dying: Contingency, Creativity and Conflict in Western Kenya. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Gregg, M., and G.J. Seigworth. 2010. The Affect Theory Reader. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Gust, D. A., Y. Pan, F. Otieno, T. Hayes, T. Omoro, P. A. Phillips-Howard, F. Odongo, and G. O. Otieno. 2017. “Factors Associated with Physical Violence by a Sexual Partner among Girls and Women in Rural Kenya.” Journal of Global Health 7 (2): 020406. doi:10.7189/jogh.07.020406

- Halkitis, P. N. 2014. The AIDS Generation: Stories of Survival and Resilience. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kylmä, J., K. Vehviläinen-Julkunen, and J. Lähdevirta. 2001. “Hope, Despair and Hopelessness in Living with HIV/AIDS: A Grounded Theory Study.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 33 (6): 764–775. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01712.x

- Mannheim, K. 1952. “The Problem of Generations.” In Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge: Collected Works, edited by Paul Kecskemeti, 276–322. New York: Routledge.

- Morris, R. C. 2008. “Rush/Panic/Rush: Speculations on the Value of Life and Death in South Africa's Age of AIDS.” Public Culture 20 (2): 199–231. doi:10.1215/08992363-2007-024

- National AIDS/STI Control Program. 2011. Guidelines for Anti-Retroviral Therapy in Kenya. 4th ed. Nairobi: Ministry of Medical Services, Republic of Kenya. https://healthservices.uonbi.ac.ke/sites/default/files/centraladmin/healthservices/Kenya%20Treatment%20Guidelines%202011.pdf

- Nguyen, V.-K., C. Y. Ako, P. Niamba, A. Sylla, and I. Tiendrébéogo. 2007. “Adherence as Therapeutic Citizenship: Impact of the History of Access to Antiretroviral Drugs on Adherence to Treatment.” AIDS 21 (Suppl 5): S31–S5. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000298100.48990.58

- Niehaus, I. 2018. AIDS in the Shadow of Biomedicine: Inside South Africa's Epidemic. London: Zed Books.

- Nsanzimana, S., E. Remera, S. Kanters, K. Chan, J. I. Forrest, N. Ford, J. Condo, A. Binagwaho, and E. J. Mills. 2015. “Life Expectancy among HIV-Positive Patients in Rwanda: A Retrospective Observational Cohort Study.” The Lancet Global Health 3 (3): e169–e177. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70364-X

- Ochieng, W., R. C. Kitawi, T. J. Nzomo, R. S. Mwatelah, M. J. Kimulwo, D. J. Ochieng, J. Kinyua, et al. 2015. “Implementation and Operational Research: Correlates of Adherence and Treatment Failure among Kenyan Patients on Long-Term Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy.” Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 69 (2): e49–e56. doi:10.1097/QAI.0000000000000580

- Ochieng-Ooko, V., D. Ochieng, J. E. Sidle, M. Holdsworth, K. Wools-Kaloustian, A. M. Siika, C. T. Yiannoutsos, M. Owiti, S. Kimaiyo, and P. Braitstein. 2010. “Influence of Gender on Loss to Follow-up in a Large HIV Treatment Programme in Western Kenya.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization 88 (9): 681–688. doi:10.2471/BLT.09.064329

- Okewo, C., and E. Mungai. 2014. “Why Life's Short in Not So Poor Kenyan Counties.” The Daily Nation. Nairobi, March 10. https://reliefweb.int/report/kenya/why-lifes-short-not-so-poor-kenyan-counties

- Owczarzak, J. 2009. “Defining HIV Risk and Determining Responsibility in Postsocialist Poland.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 23 (4): 417–435. doi:10.1111/j.1548-1387.2009.01071.x

- Prince, R. 2012. “HIV and the Moral Economy of Survival in an East African City.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 26 (4): 534–556. doi:10.1111/maq.12006

- Reynolds Whyte, S. 2014. Second Chances: Surviving AIDS in Uganda. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Rutherford, D. 2016. “Affect Theory and the Empirical.” Annual Review of Anthropology 45 (1): 285–300. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-102215-095843

- Sagar, J. M. 2013. A Forgotten Generation: Long-Term Survivors' Experiences of HIV and AIDS. Scotts Valley, CA: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Salmen, C. R., M. D. Hickey, K. J. Fiorella, D. Omollo, G. Ouma, D. Zoughbie, and M. R. Salmen. 2015. “Wan Kanyakla” (We Are Together): Community Transformations in Kenya following a Social Network Intervention for HIV Care.” Social Science & Medicine 147: 332–340. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.021

- Scheper-Hughes, N. 1993. Death without Weeping: The Violence of Everyday Life in Brazil. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Shand, T., H. Thomson-de Boor, W. van den Berg, D. Peacock, and L. Pascoe. 2014. “The HIV Blind Spot: Men and HIV Testing, Treatment and Care in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Institute of Development Studies Bulletin 45 (1): 53–60. doi:10.1111/1759-5436.12068

- Skoggard, I., and A. Waterston. 2015. “Introduction: Toward an Anthropology of Affect and Evocative Ethnography.” Anthropology of Consciousness 26 (2): 109–120. doi:10.1111/anoc.12041

- Stewart, K. 2007. Ordinary Affects. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Thieme, T. A. 2013. “The “Hustle” Amongst Youth Entrepreneurs in Mathare's Informal Waste Economy.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 7 (3): 389–412. doi:10.1080/17531055.2013.770678

- UNAIDS. 2014. “Fast-Track - Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030.” Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/JC2686_WAD2014report

- Young, P. W., A. A. Kim, J. Wamicwe, L. Nyagah, C. Kiama, J. Stover, J. Oduor, et al. 2017. “HIV-Associated Mortality in the Era of Antiretroviral Therapy Scale-Up – Nairobi, Kenya, 2015.” PLoS One 12 (8): e0181837. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181837