Abstract

Good sexual health requires navigating intimate relationships within diverse power dynamics and sexual cultures, coupled with the complexities of increasing biomedicalisation of sexual health. Understanding this is important for the implementation of biomedical HIV prevention. We propose a socially nuanced conceptual framework for sexual health literacy developed through a consensus building workshop with experts in the field. We use rigorous qualitative data analysis to illustrate the functionality of the framework by reference to two complementary studies. The first collected data from five focus groups (FGs) in 2012 (n = 22), with gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men aged 18–75 years and 20 in-depth interviews in 2013 with men aged 19–60 years. The second included 12 FGs in 2014/15 with 55 patients/service providers involved in the use/implementation of HIV self-testing or HIV prevention/care. Sexual health literacy goes well beyond individual health literacy and is enabled through complex community practices and multi-sectoral services. It is affected by emerging (and older) technologies and demands tailored approaches for specific groups and needs. The framework serves as a starting point for how sexual health literacy should be understood in the evaluation of sustainable and equitable implementation of biomedical sexual healthcare and prevention internationally.

Introduction

Sexual encounters comprise multiple, interacting interpersonal and social elements. Applying learned information to make sexual health decisions requires a myriad of multi-levelled interpersonal skills to negotiate with sexual partners about complex risk information in dynamic circumstances. These socially acquired skills require the navigation of diverse power dynamics, verbal and non-verbal communication, and multiple, sexual scripts (Gagnon and Simon Citation1973), which are in turn modified within specific sexual cultures (Parker, Herdt, and Carballo Citation1991).

Changes in sexual cultures, practices and norms include the development of new, varied and often digitalised ways to connect sexually (Davis et al. Citation2016). Moreover, the biomedicalisation of sexual health and HIV, which includes the use of antiretroviral medications for HIV prevention (e.g. pre-exposure prophylaxis [Young, Flowers, and McDaid Citation2016]) as well as new technologies for self-testing and individual risk management (Flowers, Riddell, et al. Citation2017; Flowers, Estcourt, et al. Citation2017), presents challenges for gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men to interpret and manage (Prestage et al. Citation2019; Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019; Malone et al. Citation2018; Young et al. Citation2019). Enhancing health literacy could contribute to improving health by supporting men to navigate these increasingly complex sexual information landscapes.

A number of different health literacy frameworks have been suggested (Sørensen et al. Citation2012; American Medical Association Citation1999; Nutbeam Citation2000, Citation2008; Peerson and Saunders Citation2009). Nutbeam’s health literacy model in particular has been influential, describing how individuals require functional literacy to understand health information, interactive literacy to interpret and use information and to communicate with others and critical literacy to analyse and question information to exercise more control over health decisions and behaviours (Nutbeam Citation2000). This and other broad definitions recognise that health literacy extends beyond the individual to the healthcare system and wider society, and is shaped by changing individual-level and social, structural and cultural determinants (Sørensen et al. Citation2012; Rootman and Gordon-El-Bihbety Citation2008; Zarcadoolas, Pleasant, and Greer Citation2005; Nutbeam Citation2008).

Something of this complexity is highlighted in the development of specific sub-concepts such as ‘oral health literacy’, ‘environmental health literacy’, and ‘mental health literacy’ (Brijnath et al. Citation2016; Pleasant et al. Citation2016). Sexual literacy as a concept was introduced when Reinisch and Beasley (Citation1990) suggested accurate knowledge of sexual and reproductive health, along with attitudes towards sexuality and fertility were important parts of this. Other studies have recognised the importance of individuals’ skills development in managing sexual health and wellbeing, as well as the need to focus on broader contextual and structural influences (McMichael and Gifford Citation2009; Jones and Norton Citation2007; Manduley et al. Citation2018).

Some studies have applied (existing and tailored) health literacy measures to our understanding of treatment adherence and health outcomes among people living with HIV (Perazzo, Reyes, and Webel Citation2017; Reynolds et al. Citation2019). Much of this research has focused on young people and/or the individual-level (Haruna et al. Citation2019; Freeman et al. Citation2018; Vamos et al. Citation2018; Lin, Zhang, and Cao Citation2018; Kaczkowski and Swartout Citation2019) and while a few studies have begun to examine health literacy inequities among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (Rosenberger et al. Citation2011; Manduley et al. Citation2018; Gilbert et al. Citation2019; Brookfield et al. Citation2019; Rucker et al. Citation2018; Eliason, Robinson, and Balsam Citation2018; Oliffe et al. Citation2019), sexual health literacy as a concept remains under-developed.

Sexual health literacy for gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men is critical given they continue to bear a disproportionate burden of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (Beyrer et al. Citation2016). As new information about HIV transmission risk has emerged, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men have historically developed and adopted new prevention strategies (Flowers Citation2001; Rönn et al. Citation2014; Kippax and Race Citation2003). The addition of biomedical prevention demands that men navigate increasingly complex information (Young et al. Citation2019; Young, Flowers, and McDaid Citation2016; Prestage et al. Citation2019; Jin et al. Citation2015; Martinez-Lacabe Citation2019) as must their healthcare providers, in order effectively to communicate up-to-date information. All of this takes place within the context of profound systemic factors that affect the health of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, including stigma and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and HIV, as well as inadequate access to appropriate healthcare services (Beyrer et al. Citation2012). Fully realising the benefits of and implementing biomedical HIV prevention at scale requires that the communities most affected are made aware, educated and empowered to access it, while at the same time challenging the many entrenched forms of stigma preventing this (Young et al. Citation2019; Young, Flowers, and McDaid Citation2016; Brookfield et al. Citation2019). It is for this reason that we argue that gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men’s sexual health literacy should capture the individual as always embedded within multiple, intersectional social contexts. We define sexual health literacy as comprised of the skills and capacity to understand and employ health information in a sexual environment which considers more than the individual and is shaped by historical context, complex community practices, diverse health services and existing and emerging testing technologies. Supporting sexual health literacy requires a tailored approach to address the specific social, cultural and biomedical needs of diverse communities.

In this paper, we propose a comprehensive framework for gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men’s sexual health literacy, which can be used in future research to inform sustainable and equitable implementation of biomedical sexual healthcare and prevention. Our framework is dynamic, comprehensive and grounded in the complex social structures that determine it, building on the models proposed by pre-existing and well tested frameworks for broader health literacy (e.g. Sørensen et al. Citation2012; Nutbeam Citation2008), while incorporating consensus from experts in sexual health. We illustrate the framework and the current complexity of sexual healthcare and HIV prevention that has to be reflected within it through a rigorous secondary analysis of complementary data from two UK studies related to gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, HIV, testing and prevention.

Methods

Consensus building workshop

The 2014 British Columbia Gay Men’s Health Summit (http://cbrc.net/summit) in Vancouver, Canada focused on health literacy and its application to sexual health. Following the Summit, we held a one-day consensus building workshop with 38 researchers, service providers, policy makers and knowledge users working in HIV prevention, sexual health and health literacy. The majority of participants identified as gay. We used World Café methodology, involving concurrent multi-layered small group discussions of a set of critical, topic-specific questions (Brown and Isaacs Citation2005). This method allows multiple perspectives and the building of consensus around a topic as participants move between groups and build on the discussions of others. Our World Café was structured around three rounds of discussion, each relating to a different aspect of sexual health literacy adapted from frameworks linking health literacy to health outcomes (Paasche-Orlow and Wolf Citation2007): users, providers, and systems. Following the last round, participants were divided into three groups to review discussion notes and summarise key themes to inform development of the conceptual framework (Gilbert et al. 2015).

Secondary data analysis

We draw on secondary data analysis to illustrate framework themes from two UK studies which reflect the views of the range of stakeholders, including gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men and their sexual health providers, for whom sexual health literacy is a concern. These studies included diverse participants in terms of lifecourse, serostatus, geography and experience of health care and/or provision. While each study did not explicitly look at sexual health literacy, both identified it as a key issue.

HIV and the biomedical

We draw on data with gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men across Scotland from a study on the acceptability of biomedical HIV prevention (Young, Flowers, and McDaid Citation2016; Young et al. Citation2019). These data included five exploratory focus groups (FGs) in 2012 (n = 22), with men aged 18–75 years and 20 in-depth interviews (IDIs) in 2013 with men aged 19–60 years. Participants were recruited through advertisements in sexual health centres, community organisations and commercial venues. FGs and IDIs were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were anonymised and coded in NVIVO V.10 (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2012). Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Glasgow, College of Social Sciences Ethics Committee (Ref. No: CSS2012/0193; CSS2012/0264).

Exploring transformative technologies in sexual health (ETTISH)

Data are drawn from 12 FGs in 2014/15 with 55 multi-professional, patients and providers who were involved in HIV self-testing and/or prevention and care (Flowers, Estcourt, et al. Citation2017). Participants were recruited through existing connections with organisations across a range of urban and rural areas. Three FGs were conducted with heterogeneous gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, six included health professionals/providers, and three included varied staff from community organisations, activist groups and commercial businesses with vested interests (i.e. sex shop and saunas). Data were transcribed and analysed thematically using NVIVO V.10. Ethical approval was given by Glasgow Caledonian University and NHS R&D approval for NHS Project ID: 164239; R&D2014AA089.

Synthesis and integration of findings with the sexual health literacy framework

Using a data synthesis approach (Dixon-Woods et al. Citation2005), the key thematic findings related to sexual health literacy from each of the above studies were identified and combined within a single matrix across the five levels of our conceptual framework. These findings illustrate where and when sexual health literacy issues were evident. Rigour throughout the integrative analysis was achieved by the matrix being interpreted by the first and last authors, with a consensus reached via iterative analysis and discussion across all authors.

Results

Conceptual framework for sexual health literacy

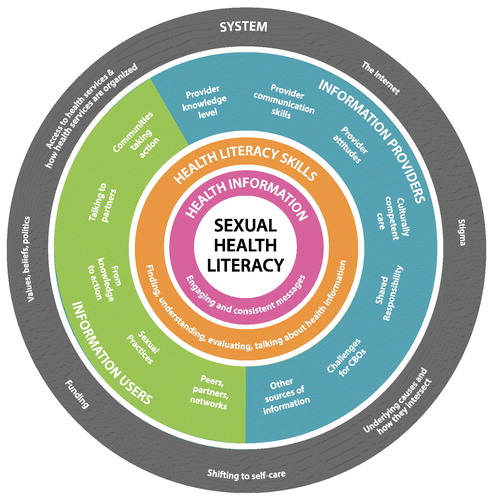

Our conceptual framework for sexual health literacy emerged from the consensus building workshop (). Drawing on the socio-ecological framework (McLaren and Hawe Citation2005), it identifies five interrelated components, which together offer a comprehensive conceptualisation of sexual health literacy, beyond individual attitudes and behaviours:

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men’s sexual health literacy.

Health information: The provision of health information to individuals is central to and affected by the consistency of messages across multiple information sources, and how messages engage people (both in terms of content and delivery).

Health literacy skills: A full range of health literacy skills, including how individuals find, understand, evaluate and discuss health information, are needed in order to apply new (and existing) information in practice.

Information users: Peers, sexual partners, sexual practice within wider sexual networks, and community mobilisation influence when and why people find, understand and evaluate sexual health information. Translating sexual health knowledge into action is contingent on this, alongside social context, motivation and lived experience.

Information providers: Healthcare providers and community-based organisations (CBOs) are critical in improving and supporting health literacy. This requires providers to possess effective communication skills and sufficient knowledge on the specific sexual health concerns of different sub-populations. It also requires them to be adequately prepared to share information relevant to the community in question, and have an awareness of the influence of their own attitudes towards sexuality on health literacy and information delivery. Health literacy is a shared responsibility between providers and users, with users acting as co-creators of knowledge.

Systems: There are a number of underlying social and structural drivers of sexual health and it is important to consider what role they play and how they interact. The health system is a key determinant of health literacy, both in terms of access to and organisation of health services. This is affected by programme and policy priorities, economic constraints, and the variety of services provided, as well as shifts towards self-care. Digital and social media across all aspects of life (including access to commercial and peer sources of information) plays an important role by facilitating timely access to relevant information in engaging and interactive formats. Structural drivers of inequalities and wider social factors – our values, beliefs, and political systems – can drive stigma and discrimination, and intersect with oppressions such as racism, and classism.

The five interrelated levels draw on individual, interpersonal, social and systemic factors associated with sexual health, and operate in conjunction with one another to shape sexual health literacy and the environment within which it operates.

The matrix of the integrated qualitative synthesis of themes across the five levels of our conceptual framework is shown in , which notes the thematic findings of each study as they relate to the five framework levels. Below we provide exemplar quotes that illustrate these findings.

Table 1. Integration of thematic findings from the HIV and the Biomedical and Exploring Transformative Technologies in Sexual Health studies against the conceptual framework for gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men’s sexual health literacy.

Health information

Awareness, content, consistency and how information and messages are delivered are central to sexual health literacy. Our research demonstrated that participants were conscious of inconsistent messaging relating to HIV prevention, treatment and care, and that conflicting or multiple messages lead to uncertainty:

I think again the risk is by giving too many instructions, that people get blinded by words so they can't actually, they would look at that and think phew, and they’ll not bother, I’ll put it away and do it another day. (ETTISH Project, NHS staff, Rural Health board)

Barriers to the use of self-testing include failure to communicate information and reliance upon written language and voluminous text:

I'm looking at this instructions thing and they might as well be asking me to build a rocket. That is, you know, Ikea have better instructions than this. […] Because there’s so much, so many steps at each bit, that's what it’s like seven or eight steps in each (ETTISH Project, Gay men, urban area)

While the clinical effectiveness of biomedical HIV prevention and self-testing is well established, actual and effective use by individuals requires increasing levels of HIV knowledge (clinical and otherwise) and combining HIV prevention with the everyday realities of having sex and managing health. Biomedical prevention can challenge existing, deeply engrained, socially embedded understandings of HIV and has the potential to disrupt existing prevention strategies. Using biomedical prevention requires ongoing, regular engagement with clinical services and an understanding of complicated information concerning treatment adherence, viral activity and suppression and risks of onwards transmission. These factors raise critical issues relating to inequalities and access. Although biomedical prevention may be accessed and work best for those already engaged in regular healthcare, their uptake and use of this prevention method should not be taken for granted. In our studies, some of those who had been actively engaging with HIV care and treatment for years were unaware of the implications of an undetectable viral load on transmission: ‘I mean if I’m not infectious there may not be anything to worry about, why have I been in hibernation?’ (HIV and the Biomedical Project, HIV-positive gay man).

Health literacy skills

Awareness must be accompanied by skills to understand, evaluate and communicate health information for individuals to put knowledge into practice. The functional health literacy demands of using biomedical HIV prevention and self-testing correctly can be offset by the use of visual aids, such as video or pictorial guides, which describe the process in a step by step format. However, they often require both numeracy and reading comprehension, as well as manual dexterity and the cognitive capacity to read, follow and implement test instructions. Information on how interventions work is also important. For instance, knowing how to interpret the effectiveness of an undetectable HIV viral load in combination with other prevention strategies will require a set of particular skills in risk calculation. A HIV-negative participant in one of our studies jokingly explained:

But there's obviously still a 10% risk but, as you said, there's the same risk with condoms. So it's either you take the 10% risk or you say 'well, I'll use condoms and we'll use TASP' which makes 180%. (Laugh) (HIV and the Biomedical Project, HIV-negative gay man).

This suggests individuals need a critical understanding of new HIV testing and treatment options, especially in the context of, or combined with, other existing prevention practices (e.g. condom use) in order to action and benefit from these.

Information users

How to negotiate and communicate complex and combined HIV prevention with others was raised as a concern. Negotiating HIV prevention requires communication of relevant information (e.g. viral loads, ARVs) to sexual partners who may have less knowledge of these. One participant living with HIV explained his hesitancy:

… this guy I'm seeing now, you know, I'd like to have bareback [condomless] sex wi' him. But thinking how do I bring that issue up with him? And how would he… what would he think of me then? Would he be thinking… you're willing to put my life at risk,' you know? Because he wouldn't know anything about… I feel, I sometimes feel like saying to him ‘I've printed all this off for you, go and read it’. But that's forcing somebody into something… (HIV and the Biomedical Project, HIV-positive gay man)

Unequal power relations in intimate relationships may prevent open discussions and such inequalities can be marked by gender, age, income or, as above, HIV status. However, the advent of biomedical prevention could also facilitate more open discussion within sero-discordant relationships (Persson Citation2008).

Information providers

Healthcare providers are critical in improving and supporting health literacy, but the politics and pace of change can lead to inconsistencies in the messages being relayed. We found service providers doubted users’ abilities to understand and interpret complex health information:

Participant 2: I was going to say if they're doing it at home, do they know their risks with their incubation periods? So, are they actually getting an accurate test? Is it a good sample? Same as this issue with this is are they going to make good samples?

Participant 5: Are they going to be falsely reassured by a negative, when they're actually still within the period or they have not held on to the urine for long enough before they pee?

Participant 4: Or swabbed properly. (ETTISH Project, NHS staff, Rural Health board)

The quote above suggests that service providers could fail to see men as potential co-creators of knowledge or having the competence to understand sexual health risk; a significant barrier to effective engagement. In contrast, there is evidence of the co-creation of safer sex practices among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, where the boundary between expert and lay knowledge has been blurred (Kippax and Race Citation2003, Race Citation2017).

System factors

Sexual health is affected by profound health systems and social change, driven by several factors including diminishing public spending. Equally, wider sociocultural and technological changes are increasingly mediated across remote and digital platforms. In the extract below, the health professional details the economic rationale behind the move to self-testing:

A kit like this available through the post, I think that this is a cost cutting device, because you're not having to have people to come in and see a nurse and then a consultant and have all this set up for everyone getting tested. I mean how expensive can it be to create a swab, how expensive is it to post a kit as opposed to half an hour of a consultant’s time? (ETTISH project, Community Pharmacy Advisor, Rural Health Board)

While increasing access to self-testing was viewed as a potential means of decreasing stigma (Flowers, Riddell, et al. Citation2017), our studies also suggested that HIV stigma and existing social barriers continue to prevent open discussion of HIV. One participant describes how he negotiated non-disclosure of his HIV-status in an encounter with another, younger HIV-negative gay man:

I mean I bumped into an eighteen year old, so young, somewhere down the line through nothing I said brought up sort of HIV with some level of awareness but you know, ‘not that I’ve got HIV or anything or what is it, AIDS, I haven’t got the AIDS’. You know, that’s still what people are talking about and when you start to say even in similar term- ‘well, HIV’s not AIDS babe’. ‘Oh how do you know, have you got it?’ … sort of thing. It kinda puts you into- and when I could start saying all about CD4 counts and viral loads and medications and it’s a chronic illness, you know, it’s no longer considered fatal… it does, I think it starts to expose you a little. (HIV and the Biomedical Project, HIV-positive gay man)

Despite recent activist campaigns around U = U (i.e. undetectable = untransmittable, which is a recent campaign to highlight that people on effective treatment cannot transmit HIV) and the potential for biomedical HIV prevention, gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men living with HIV will continue to be faced with the outdated knowledge of their peers and wider society (Young et al. Citation2019). Consequentially, for some men, having too much HIV knowledge in an environment where openly talking about HIV is not the norm, poses a potential and significant social risk. It is important, then, to consider not only the sexual health literacy of people affected by HIV, but also that of their peers, their community and the wider social context in which they are required to deploy this knowledge.

Discussion

Our conceptual framework for gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men’s sexual health literacy engages with the socially situated nature of sexual health: it explicitly recognises the importance of focusing on providers of information as well as individuals as users of information; and acknowledges the structural and systemic factors that impact on health. In doing so, it combines the social situatedness of sexual health practices with the complexities of health literacy for men. Applying specifically to sexual health, it builds on Nutbeam’s three-part model of functional, interactive and critical health literacy (Nutbeam Citation2000), and the broader definitions of health literacy that recognise dynamic and societal influences (Sørensen et al. Citation2012; Nutbeam Citation2000; Rootman and Gordon-El-Bihbety Citation2008; Zarcadoolas, Pleasant, and Greer Citation2005; Nutbeam Citation2008). It extends the existing and limited field of sexual health literacy research (Freeman et al. Citation2018; Vamos et al. Citation2018; Lin, Zhang, and Cao Citation2018; Haruna et al. Citation2019; Kaczkowski and Swartout Citation2019), particularly among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (Rosenberger et al. Citation2011; Eliason, Robinson, and Balsam Citation2018; Oliffe et al. Citation2019; Manduley et al. Citation2018; Gilbert et al. Citation2019; Brookfield et al. Citation2019; Rucker et al. Citation2018), by advocating a multi-level approach to enable men to attain sexual health literacy in the context of social and cultural practices and forces that shape it. There is a challenge for communities to manage sexual health within the wider context of social stigma and shrinking healthcare services, while increasingly being asked to become (bio)medical experts in their own sexual healthcare. As such, the framework could allow for more nuance in studies of awareness and uptake of biomedical sexual healthcare and prevention (e.g. going beyond measures of knowledge and use) to look at underlying determinants suggested by it. We propose it as a starting point for this purpose and suggest avenues for future research in the discussion that follows.

To achieve sustainable and equitable implementation of biomedical sexual healthcare and prevention, further research is required to examine how to reach men with diverse sexual health literacy needs (Frankis et al. Citation2016; Flowers, Estcourt, et al. Citation2017; Flowers, Riddell, et al. Citation2017), and to assess how to present clear and consistent messages across multiple communities within a rapidly changing scientific and politically charged environment that may lack interpretative agreement. For instance, while the efficacy of biomedical HIV prevention is now without question, there are ongoing issues in translating these clinical understandings into and within community practice (Witzel, Nutland, and Bourne Citation2019). Accounting for the complexity of prevention, testing and treatment science, and making developments accessible across a range of health literacy skills, is a key challenge in policy and practice.

We also need to better understand how to influence moving from knowledge to action and explore what strategies would be effective in enhancing communication with partners. Information sharing about sexual health between peers, partners, and in networks is both common and important to gay and bisexual men, although indirect methods might be used (e.g. code words such as ‘needs discussion’ to negotiate sero-adaptive strategies) (Race Citation2015). There is mixed evidence of the success of peer and community engagement in facilitating sexual health improvement and HIV prevention (Trapence et al. Citation2012; Krishnaratne et al. Citation2016), and future research could explore how to develop this approach to improve sexual health literacy at the community-level.

Our framework has reflected on how cultural competency to work with gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men is critical in policy and practice. Actioning this requires that we learn from examples of best practice internationally where cultural competency has been well established (Mayer et al. Citation2008). It requires provision of training, but also efforts to address the power imbalance to enable providers (from all sectors) to work with users as co-creators to generate new knowledge. Face-to-face, interpersonal interaction with health care is diminishing in some settings, but our research has demonstrated that an unintended consequence could be the loss of linkage to holistic health care (Flowers, Estcourt, et al. Citation2017), reducing the opportunities for broader, syndemic health inequities to be addressed. It is important to recognise that whilst the Internet and social media represent opportunities to improve provision and engagement with information and services, there are also concerns that such a focus could fuel health inequalities and adversely influence sexual behaviours and practices (Elwick et al. Citation2013; Aicken et al. Citation2016; Horvath et al. Citation2013). Further work is required to counter the impact of HIV-related stigma and discrimination and to ensure health service equity (regardless of health literacy skills), as is research to address heterogeneity and intersectionalities among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in relation to health literacy (Mackenzie Citation2019; Semlyen, Ali, and Flowers Citation2018).

In considering sexual health literacy in five dimensions there is scope for compensating problems at one level with intensifying solutions at others. A uni-dimensional understanding of sexual health literacy cannot lever such agility. Instead our framework incorporates broad systemic sectors (such as education or legal systems), which generate and reinforce many of the structural drivers of sexual health inequities and is therefore well aligned with current theoretical models (such as syndemic theory, social determinants of health, as well as more traditional individualised approaches) for improving sexual health. It emphasises the need to address social, syndemic and systemic factors associated with ill health (Mendenhall Citation2017; Rutter et al. Citation2017).

Limitations

Our qualitative research studies are subject to the usual limitations on generalisability and were conducted before new biomedical prevention and self-testing technologies were widely available. It is critical to consider the anticipation, and potential barriers to implementation, of biomedical prevention and self-testing technologies within communities and health systems.

The absence of lived experience with these technologies can still uncover much, such as how access to new technologies may be affected by existing inequalities such as urbanicity, or proximity to gay communities/health services. Even with increased access, new users will likely be unfamiliar with existing interventions/services. The heterogeneity of the data enables critical engagement with sexual health literacy with geographic, life course and professional/lay input.

It should also be noted that the components of our theoretical framework were identified by workshop participants and thus, do not represent a fully comprehensive representation of all aspects that could be part of this framework.

Additionally, our theoretical framework has been developed in the context of gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men’s health in high income countries (and state-funded health systems) and will need to be further refined for use with men in low- and middle-income countries and with other populations more broadly.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have advanced a new theoretical framework to understand sexual health literacy in action, one that is grounded and enabled through complex community practices, multi-sectoral services, affected by emerging (and older) technologies and demands tailored approaches for specific groups and needs. We propose using it as a starting point for future research, which in turn could inform policy and practice through the design of effective multilevel interventions to enhance sexual health literacy. This could ultimately support sustainable and equitable implementation of biomedical sexual healthcare and prevention internationally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aicken, C. R., C. S. Estcourt, A. M. Johnson, P. Sonnenberg, K. Wellings, and C. H. Mercer. 2016. “Use of the Internet for Sexual Health among Sexually Experienced Persons Aged 16 to 44 Years: Evidence from a Nationally Representative Survey of the British Population.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 18 (1): e14.

- American Medical Association. 1999. “Health Literacy: Report of the Council on Scientific Affairs.” JAMA 281 (6): 552–557.

- Beyrer, C., S. D. Baral, C. Collins, E. T. Richardson, P. S. Sullivan, J. Sanchez, G. Trapence, et al. 2016. “The Global Response to HIV in Men Who Have Sex with Men.” The Lancet 388 (10040): 198–206.

- Beyrer, C., P. S. Sullivan, J. Sanchez, D. Dowdy, D. Altman, G. Trapence, C. Collins, et al. 2012. “A Call to Action for Comprehensive HIV Services for Men Who Have Sex with Men.” The Lancet 380 (9839): 424–438.

- Brijnath, B., J. Protheroe, K. R. Mahtani, and J. Antoniades. 2016. “Do Web-Based Mental Health Literacy Interventions Improve the Mental Health Literacy of Adult Consumers? Results from a Systematic Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 18 (6): e165.

- Brookfield, S., J. Dean, C. Forrest, J. Jones, and L. Fitzgerald. 2019. “Barriers to Accessing Sexual Health Services for Transgender and Male Sex Workers: A Systematic Qualitative Meta-Summary.” AIDS & Behavior. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02453-4

- Brown, J., and D. Isaacs. 2005. The World Café: Shaping Our Futures through Conversations That Matter. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

- Davis, M., P. Flowers, K. Lorimer, J. Oakland, and J. Frankis. 2016. “Location, Safety and (Non) Strangers in Gay Men’s Narratives on ‘Hook-Up’ Apps.” Sexualities 19 (7): 836–852.

- Dixon-Woods, M., S. Agarwal, D. Jones, B. Young, and A. Sutton. 2005. “Synthesising Qualitative and Quantitative Evidence: A Review of Possible Methods.” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10 (1): 45–53.

- Eliason, M. J., P. Robinson, and K. Balsam. 2018. “Development of an LGB-Specific Health Literacy Scale.” Health Communication 33 (12): 1531–1538.

- Elwick, A., K. Libao, J. Nutt, and A. Simon. 2013. Beyond the Digital Divide: Young People and ICT. Reading: CfBT Trust.

- Flowers, P. 2001. “Gay Men and HIV/AIDS Risk Management.” Health 5 (1): 50–75.

- Flowers, P., C. Estcourt, P. Sonnenberg, and F. Burns. 2017. “HIV Testing Intervention Development among Men Who Have Sex with Men in the Developed World.” Sexual Health 14 (1): 80–88.

- Flowers, P., J. Riddell, C. Park, B. Ahmed, I. Young, J. Frankis, M. Davis, et al. 2017. “Preparedness for Use of the Rapid Result HIV Self-Test by Gay Men and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM): A Mixed Methods Exploratory Study among MSM and Those Involved in HIV Prevention and Care.” HIV Medicine 18 (4): 245–255.

- Frankis, J., I. Young, P. Flowers, and L. McDaid. 2016. “Who Will Use Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Why?: Understanding PrEP Awareness and Acceptability Amongst Men Who Have Sex with Men in the UK – A Mixed Methods Study.” PLoS ONE 11 (4): e0151385.

- Freeman, J. L., P. H. Caldwell, P. A. Bennett, and K. M. Scott. 2018. “How Adolescents Search for and Appraise Online Health Information: A Systematic Review.” The Journal of Pediatrics 195: 244–255.

- Gagnon, J. H., and W. Simon. 1973. Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality. London: Hutchinson and Co. Ltd.

- Gilbert, M., W. Michelow, J. Dulai, D. Wexel, T. Hart, I. Young, S. Martin, P. Flowers, L. Donelle, and O. Ferlatte. 2019. “Provision of Online HIV-Related Information to Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Health Literacy-Informed Critical Appraisal of Canadian Agency Websites.” Sexual Health 16 (1): 39–46.

- Gilbert, M., J. Dulai, D. Wexel, O. Ferlatte, and the Health Literacy Planning Grant Team. 2015. Health Literacy, Sexual Health and Gay Men. Current Perspectives: Report from a Meeting of Researchers, Policy-Makers, Service Providers and Community Members Funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Toronto, Ontario: Ontario HIV Treatment Network.

- Haruna, H., X. Hu, S. K. W. Chu, and R. R. Mellecker. 2019. “Initial Validation of the MAKE Framework: A Comprehensive Instrument for Evaluating the Efficacy of Game-Based Learning and Gamification in Adolescent Sexual Health Literacy.” Annals of Global Health 85 (1): 19.

- Horvath, M. A. H., L. Alys, K. Massey, A. Pina, M. Scally, J. R. Adler. 2013. Basically…Porn is Everywhere. London: Office of the Children's Commissioner.

- Jin, F., G. P. Prestage, L. Mao, I. M. Poynten, D. J. Templeton, A. E. Grulich, and I. Zablotska. 2015. “‘Any Condomless Anal Intercourse’ is No Longer an Accurate Measure of HIV Sexual Risk Behavior in Gay and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men.” Frontiers in Immunology 6: 86. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2015.00086

- Jones, S., and B. Norton. 2007. “On the Limits of Sexual Health Literacy: Insight from Ugandan Schoolgirls.” Diaspora, Indigenous and Minority Education: Studies of Migration, Integration, Equity and Cultural Survival 1 (4): 285–305.

- Kaczkowski, W., and K.M. Swartout. 2019. “Exploring Gender Differences in Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy among Young People from Refugee Backgrounds.” Culture, Health & Sexuality. doi:10.1080/13691058.2019.1601772

- Kippax, S., and K. Race. 2003. “Sustaining Safe Practice: Twenty Years On.” Social Science & Medicine 57 (1): 1–12.

- Krishnaratne, S., B. Hensen, J. Corde, J. Enstone, and J.R. Hargreaves. 2016. “Interventions to Strengthen the HIV Prevention Cascade: A Systematic Review of Reviews.” The Lancet HIV 3 (7): e307–e317.

- Lin, W. Y., X. Zhang, and B. Cao. 2018. “How Do New Media Influence Youths’ Health Literacy? Exploring the Effects of Media Channel and Content on Safer Sex Literacy.” International Journal of Sexual Health 30 (4): 354–365.

- Mackenzie, S. 2019. “Reframing Masculinity: Structural Vulnerability and HIV among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men and Women.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 21 (2): 175–187.

- Malone, J., J. L. Syvertsen, B. E. Johnson, M. J. Mimiaga, K. H. Mayer, and A. R. Bazzi. 2018. “Negotiating Sexual Safety in the Era of Biomedical HIV Prevention: Relationship Dynamics among Male Couples Using Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (6): 658–672.

- Manduley, A. E., A. E. Mertens, I. Plante, and A. Sultana. 2018. “The Role of Social Media in Sex Education: Dispatches from Queer, Trans, and Racialized Communities.” Feminism & Psychology 28 (1): 152–170.

- Martinez-Lacabe, A. 2019. “The Non-Positive Antiretroviral Gay Body: The Biomedicalisation of Gay Sex in England.” Culture, Health & Sexuality. doi:10.1080/13691058.2018.1539772

- Mayer, K. H., J. B. Bradford, H. J. Makadon, R. Stall, H. Goldhammer, and S. Landers. 2008. “Sexual and Gender Minority Health: What We Know and What Needs to Be Done.” American Journal of Public Health 98 (6): 989–995.

- McLaren, L., and P. Hawe. 2005. “Ecological Perspectives in Health Research.” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 59 (1): 6–14.

- McMichael, C., S. Gifford. 2009. “It's Good to Know Now…before It's Too Late”: Promoting Sexual Health Literacy Amongst Resettled Young People with Refugee Backgrounds.” Sexuality & Culture 13 (4): 218–236.

- Mendenhall, E. 2017. “Syndemics: A New Path for Global Health Research.” The Lancet 389 (10072): 889–891.

- Nutbeam, D. 2000. “Health Literacy as a Public Health Goal: A Challenge for Contemporary Health Education and Communication Strategies into the 21st Century.” Health Promotion International 15 (3): 259–267.

- Nutbeam, D. 2008. “The Evolving Concept of Health Literacy.” Social Science & Medicine 67 (12): 2072–2078.

- Oliffe, J. L., D. R. McCreary, N. Black, R. Flannigan, and S. L. Goldenberg. 2019. “Canadian Men’s Health Literacy: A Nationally Representative Study.” Health Promotion Practice. doi:10.1177/1524839919837625

- Paasche-Orlow, M. K., and M. S. Wolf. 2007. “The Causal Pathways Linking Health Literacy to Health Outcomes.” American Journal of Health Behavior 31 (1): 19–26.

- Parker, R. G., G. Herdt, and M. Carballo. 1991. “Sexual Culture, HIV Transmission, and AIDS Research.” Journal of Sex Research 28 (1): 77–98.

- Peerson, A., and M. Saunders. 2009. “Health Literacy Revisited: What Do We Mean and Why Does It Matter?” Health Promotion International 24 (3): 285–296.

- Perazzo, J., D. Reyes, and A. Webel. 2017. “A Systematic Review of Health Literacy Interventions for People Living with HIV.” AIDS & Behavior 21 (3): 812–821.

- Persson, A. 2008. “Sero-Silence and Sero-Sharing: Managing HIV in Serodiscordant Heterosexual Relationships.” AIDS Care 20 (4): 503–506.

- Pleasant, A., R. E. Rudd, C. O'Leary, M. K. Paasche-Orlow, M. P. Allen, W. Alvarado-Little, L. Myers, K. Parson, and S. Rosen. 2016. Considerations for a New Definition of Health Literacy. Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine.

- Prestage, G., L. Maher, A. Grulich, A. Bourne, M. Hammoud, S. Vaccher, B. Bavinton, M. Holt, and F. Jin. 2019. “Brief Report: Changes in Behavior after PrEP Initiation among Australian Gay and Bisexual Men.” Journal of the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes 81 (1): 52–56.

- Race, K. 2015. “‘Party and Play’: Online Hook-up Devices and the Emergence of PNP Practices among Gay Men.” Sexualities 18 (3): 253–275.

- Race, K. 2017. The Gay Science: Intimate Experiments with the Problem of HIV. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Reinisch, J. M., and R. Beasley. 1990. The Kinsey Institute New Report on Sex. New York: Macmillan.

- Reynolds, R.,. S. Smoller, A. Allen, and P. K. Nicholas. 2019. “Health Literacy and Health Outcomes in Persons Living with HIV Disease: A Systematic Review.” AIDS & Behavior. doi:10.1007/s10461-019-02432-9

- Rönn, M., P. J. White, G. Hughes, and H. Ward. 2014. “Developing a Conceptual Framework of Seroadaptive Behaviors in HIV-Diagnosed Men Who Have Sex with Men.” Journal of Infectious Diseases 210 (Suppl 2): S586–S593.

- Rootman, I., and D. Gordon-El-Bihbety. 2008. A Vision for a Health Literate Canada. Report on the Expert Panel in Health Literacy. Ottawa: Canadian Public Health Association.

- Rosenberger, J. G., M. Reece, D. S. Novak, and K. H. Mayer. 2011. “The Internet as a Valuable Tool for Promoting a New Framework for Sexual Health among Gay Men and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men.” AIDS & Behavior 15 (1): 88–90.

- Rucker, A. J., A. Murray, Z. Gaul, M. Y. Sutton, and P. A. Wilson. 2018. “The Role of Patient–Provider Sexual Health Communication in Understanding the Uptake of HIV Prevention Services among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (7): 761–771.

- Rutter, H., N. Savona, K. Glonti, J. Bibby, S. Cummins, D. T. Finegood, F. Greaves, et al. 2017. “The Need for a Complex Systems Model of Evidence for Public Health.” The Lancet 390 (10112): 2602–2604.

- Semlyen, J., A. Ali, and P. Flowers. 2018. “Intersectional Identities and Dilemmas in Interactions with Healthcare Professionals: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis of British Muslim Gay Men.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (9): 1023–1035.

- Sørensen, K., S. Van den Broucke, J. Fullam, G. Doyle, J. Pelikan, Z. Slonska, and H. Brand. 2012. “Health Literacy and Public Health: A Systematic Review and Integration of Definitions and Models.” BMC Public Health 12 (1): 80.

- Trapence, G., C. Collins, S. Avrett, R. Carr, H. Sanchez, G. Ayala, D. Diouf, C. Beyrer, and S. D. Baral. 2012. “From Personal Survival to Public Health: Community Leadership by Men Who Have Sex with Men in the Response to HIV.” The Lancet 380 (9839): 400–410.

- Vamos, C. A., E. L. Thompson, R. G. Logan, S. B. Griner, K. M. Perrin, L. K. Merrell, and E. M. Daley. 2018. “Exploring College Students’ Sexual and Reproductive Health Literacy.” Journal of American College Health. doi:10.1080/07448481.2018.1515757

- Witzel, T. C., W. Nutland, and A. Bourne. 2019. “What Are the Motivations and Barriers to Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Use among Black Men Who Have Sex with Men Aged 18–45 in London? Results from a Qualitative Study.” Sexually Transmitted Infections 95 (4): 262–266.

- Young, I., M. Davis, P. Flowers, and L. M. McDaid. 2019. “Navigating HIV Citizenship: Identities, Risks and Biological Citizenship in the Treatment as Prevention Era.” Health, Risk & Society 21 (1–2): 1–16.

- Young, I., P. Flowers, and L. McDaid. 2016. “Can a Pill Prevent HIV? Negotiating the Biomedicalisation of HIV Prevention.” Sociology of Health & Illness 38 (3): 411–425.

- Zarcadoolas, C., A. Pleasant, and D. S. Greer. 2005. “Understanding Health Literacy: An Expanded Model.” Health Promotion International 20 (2): 195–203.