Abstract

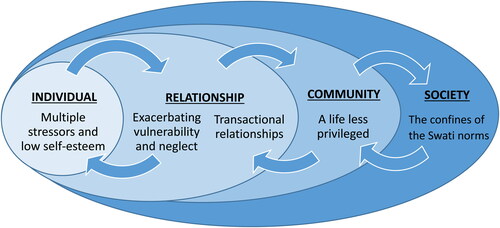

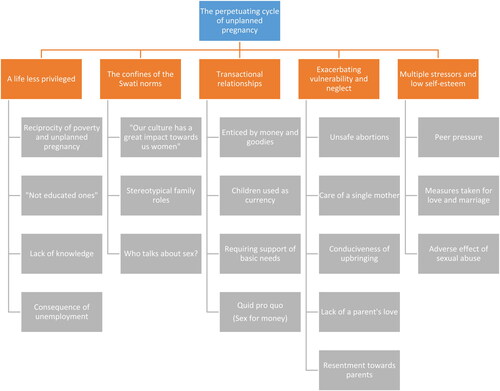

Unplanned pregnancies constitute a major health problem globally carrying negative social, economic and health consequences for individuals and families. In this study, we explored the underlying causes and implications of this phenomenon in Eswatini, a country with high rates of unplanned pregnancy. Three focus group discussions were conducted in January 2018 with female health workers called mentor mothers, chosen because they offer a twofold perspective, being both Swati women and health workers in socially and economically disadvantaged settings. Using inductive thematic analysis, we identified five sub-themes and an overarching theme called ‘the perpetuating cycle of unplanned pregnancy’ in the data. A social-ecological model was used to frame the results, describing how factors at the individual, relationship, societal and community levels interact to influence unplanned pregnancy. In this setting, factors such as perceived low self-esteem as well as poor conditions in the community drove young women to engage in transactional relationships characterised by abuse, gender inequality and unprotected sex, resulting in unplanned pregnancy. These pregnancies led to neglected and abandoned children growing up to become vulnerable, young adults at risk of becoming pregnant unintendedly, thus creating an iterative cycle of unplanned childbearing.

Introduction

Reducing the number of unplanned pregnancies is a key objective in public health to reduce the maternal mortality ratio, prevent the mother to child transmission of HIV and to empower women. Unplanned pregnancies are those that occurred when contraception is used, correctly or incorrectly, or when no contraception is used but a pregnancy was not desired (Santelli et al. Citation2003). A closely related concept is unintended pregnancies, referring to pregnancies that occurred earlier than desired (mistimed) or not wanted at all (unwanted) (Santelli et al. Citation2003).

Unplanned pregnancies carry health risks both for the mother and her offspring. Half of all unplanned pregnancies are terminated by induced abortion out of which the majority are unsafe (Sedgh, Singh, and Hussain Citation2014). Women with unwanted pregnancies are less likely to receive adequate prenatal care, more likely to suffer from postpartum depression and their babies are less likely to be breastfed and immunised (Marston and Cleland Citation2003; Cheng et al. Citation2009; Kost and Lindberg Citation2015; Amo-Adjei and Anamaale Tuoyire Citation2016). Although the risks of unplanned pregnancy are assumed to be greater in low income than in high income settings, evidence concerning their consequences in those settings is lacking (Gipson, Koenig, and Hindin Citation2008; Tsui, McDonald-Mosley, and Burke Citation2010; Pallitto, Campbell, and O'Campo Citation2005). Studies on the consequences of unplanned pregnancy have mainly been quantitative and focused on short-term health outcomes (Tsui, McDonald-Mosley, and Burke Citation2010; Gipson, Koenig, and Hindin Citation2008). Qualitative studies have identified other consequences, such as an increased risk of school-drop out, financial constraints, lack of partner support and changes in life trajectory for the mother (Levandowski et al. Citation2012; Kavanaugh et al. Citation2017). Some of these social consequences are not easily measured quantitatively and depend on the context, but they are of immense importance from a holistic health perspective, as health and social implications are intertwined.

Studies of the causes of unplanned pregnancy have mainly focused on maternal demographic and socioeconomic factors (Kost and Lindberg Citation2015). In low-income settings, unplanned pregnancies are generally associated with low socioeconomic status, younger age, being unmarried, higher parity, shorter birth-intervals and intimate partner violence (Hall et al. Citation2016; Iyun et al. Citation2018; Grace and Anderson Citation2018). Pregnancy planning is influenced by factors such as sexual behaviour, cultural values about sexuality, as well as by religious and political beliefs (Brown and Eisenberg Citation1995), many of which are context-dependent. In order to help individuals and couples achieve their desired number of children, identifying groups at risk of having an unplanned pregnancy in specific contexts is important. Qualitative methodology is needed to identify factors beyond those described in quantitative studies and may shed light on the pathways that exist between variables that often are modelled in a unidirectional way in quantitative work (Kavanaugh et al. Citation2017).

Unplanned pregnancy in Eswatini

The Kingdom of Eswatini is an absolute monarchy in Sub-Saharan Africa, known formerly as Swaziland. The dominant form of social organisation is patriarchy and the Kingdom scores high on gender inequality index (Central Statistical Office 2008; United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Citation2019). Abortion laws are restrictive, sexual violence is common and young women’s first sexual intercourse often involves coercion (Ruark et al. Citation2016; Fielding-Miller et al. Citation2019; Reza et al. Citation2009). Among eighteen countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, Eswatini has the second highest proportion of women who had exceeded their ideal parity at 52%, compared to 30% in the other countries (Van Lith, Yahner and Bakamjian Citation2013). In a study comparing thirty African countries, unwanted pregnancies were most frequent in Eswatini (Amo-Adjei and Anamaale Tuoyire Citation2016; Central Statistical Office Citation2008). In an earlier study, we found that 70% of all pregnancies among the studied population were unplanned (Niemeyer Hultstrand et al. Citation2019). Teenagers and first-time mothers were more likely to have an unplanned pregnancy and women with unplanned pregnancies were less likely to attend the recommended number of antenatal care visits.

This demographic evidence points to a context wherein Swazi women’s sexual and reproductive rights are hampered. In the light of these findings, our aim in this study was to explore the underlying causes and implications of unplanned pregnancy in a wider sense, beyond demographic determinants and short-term health effects, applying a holistic perspective on health.

Methods

Study setting and participants

The study was conducted at Siphilile Maternal and Child Health, a non-governmental organisation active in Eswatini since 2012. Siphilile educates local women to become mentor mothers according to the Philani mentor model, an evidence-based, enhanced model for community health workers (Målqvist Citation2019; le Roux et al. Citation2013). Siphilile recruits women who, despite poor conditions, have succeeded in raising healthy children, and educates these women about basic health issues such as HIV-prevention, nutrition and family planning. Mentor mothers are then assigned a geographical area where they become peer supporters for pregnant women and mothers with small children. We chose mentor mothers as informants as they offer a dual perspective on unplanned pregnancies – both as Swati women and as health workers.

At the start of 2018, Siphilile employed 53 mentor mothers active in Matsapha and Lubombo. Matsapha is an industrial suburb outside Manzini, the country’s largest city. Siphilile’s clients in Matsapha constitute a vulnerable group of women as most are unemployed, lack of food is common and the HIV-prevalence at 42% is higher than the national average (Niemeyer Hultstrand et al. Citation2019). A Siphilile office in Lubombo, a rural part of Eswatini, was started in 2016 and employed nine mentor mothers at the time of the study. One third of households in this region belong to the poorest wealth index quantile, and 30% of women have their first child before the age of 18 (Central Statistical Office and UNICEF Citation2016).

Data collection

Focus group discussions (FGDs) were chosen for data collection as they enable researchers to quickly identify a broad range of perspectives. They also enable participants to interact with each other, to clarify and expand their reasoning in light of other’s contributions (Powell and Single Citation1996). Twenty-nine mentor mothers were asked to participate face-to-face by the first author (JNH), as this number could include mentor mothers from all areas within both the Manzini and the Lubombo regions. We allowed for a 25% drop out (Powell and Single Citation1996) and scheduled nine to ten informants in each FGD. However, all mentor mothers agreed to participate; 20 from the Manzini region and nine from the Lubombo region. Three FGDs were held. The mentor mothers, hereafter referred to as the informants, answered a questionnaire about their background including own experience of contraception and pregnancy planning. The discussions were moderated in English by JNH as the informants speak it fluently. The first two FGDs were held at Siphilile’s office in Matsapha and the third FGD was held in a health facility in Lubombo, both separated from other staff.

A semi-structured discussion guide with open ended questions was developed by JNH and reviewed by the authors MM and NM. Data for the present study come from baseline FGDs conducted for a larger project in which we evaluated a reproductive health intervention. Therefore, both unplanned pregnancies and the intervention were discussed during the sessions. FGDs were audio recorded and lasted 89, 74 and 54 min each, excluding pauses.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis, ‘a method for identifying, analysing and interpreting patterns of meaning (“themes”) within qualitative data’, was used to analyse the data (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This form of analysis offers an organic approach to coding and the development of themes as well as the active roles of the researchers in these processes. It provides a systematic procedure for the generation of codes and themes, which do not simply summarise the data content but identify key features of the data, guided by the research questions.

Memos and preliminary themes were noted and recordings were transcribed verbatim starting immediately after each FGD by JNH. The transcripts were reviewed and complemented by the author KA. Pseudonyms were used for the informants. The researchers read the complete transcripts several times to gain insight into the data. JNH and KA independently generated descriptive and in vivo codes from the transcripts (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2014), labelling all segments relevant to the research question in an inductive manner. No software was used. The codes generated were then discussed and preliminary themes constructed. Negative case analysis was undertaken by searching for data elements that did not support the constructed themes. The themes were then negotiated among the authors, who have diverse experiences on the subject and different levels of familiarity with the context. Finally, the results were presented to a group of female and male Emaswati working at Siphilile, chosen because they were of different ages and had different educational backgrounds. This group gave feedback as a way to validate the results. Discussions were held continually until the authors deemed that data saturation was reached.

Ethics

The study was approved by the National Health Research Review Board in Eswatini (SHR010/2018) and the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala (2017-514). All informants were provided with oral and written information about the study and signed an informed consent form. They received no financial compensation except for lunch and money for transportation. Only JNH and the informants were present during the FGDs.

Findings

Participant characteristics are presented in . Their median age was 36 years (range 26-59 years) and median number of children was three. The results from the FGDs are presented as one over-arching theme and five sub-themes, each of which have several sub-categories ().

Figure 1. Over-arching theme, sub-themes and categories describing underlying causes and implications of unplanned pregnancy in Eswatini.

Table 1. Personal and reproductive characteristics of informants.

The perpetuating cycle of unplanned pregnancy

The central feature of all the FGDs concerned how an unplanned pregnancy led to consequences, which in turn increased the likelihood of unplanned pregnancy in the next generation, thus creating an iterative cycle of unplanned childbearing:

‘[…] most women in the house will tell you that they are afraid to talk to the husband, because the husband will tell them “I’m always busy, I’m working, what is your problem?”, such that we find the father will not be able to support the [unplanned] children. Then the children will go out there to look for love. While they are enjoying that love, they come back with all those pregnancies. And that will result in these young children dropping out from school. That is where the adversity will start.’ Luthando FGD 1

A life less privileged

The first sub-theme describes socioeconomic factors that informants connected with unplanned pregnancies, including poverty, poor or limited education as well as unemployment. Poverty bore a reciprocal relationship with unplanned pregnancy: some informants stating that poverty caused unplanned pregnancy and others that unplanned pregnancy caused poverty.

‘What I can say is that most of unplanned pregnancies often occurs to those that are less privileged. And not educated ones. So, it’s common with them.’ Tekiwe FGD 3

A reciprocal relationship was also described for education: unplanned pregnancy was more common among those less educated, and children born from unplanned pregnancies missed opportunities of education because of lack of financial resources.

‘So, from my experience of unplanned pregnancies, children most of them are unable to attend school and there’s much poverty. […] You find that there are many [children] and they are all more or less the same age, and she [the mother] begins to neglect the children, that’s all.’ Busisiwe FGD 1

The confines of Swati norms

Swati culture and its patriarchal structure was seen as playing a central role in unplanned pregnancies and affected multiple aspects of women’s lives and reproductive health. There were strong, predefined family roles in line with the Swati norm. These stereotypical family roles applied to the mother and father as well as to the gogo (the mother’s mother). One informant linked these stereotypical roles to why women gave birth to unplanned children:

‘I think it must be the cultural norms, because most of our cultural norms, when we grew up it was said that a father should work, and a mother should stay at home and the role of a mother is to give children.’ Luthando FGD 1

Informants expressed that women were viewed as entirely responsible for the unplanned pregnancy. Men could choose whether they wanted to share the responsibility of the child, and often they chose not to bear the responsibility when the child was not planned for.

‘One of my, my clients, once that girl was having the child, the boy said that “I don’t care, don’t count me at all. I didn’t say I need a child. I told you to go for family planning, what happened to you?”’ Smamile FGD 2

The lack of the father’s support altered family dynamics. As a result, the young mother looked to her own mother to provide the support that was lacking:

‘And once they find a problem, they take the baby and drop them to the gogo’s at home, old mothers at home. So, that old woman can’t even now walk, but you will find her with the baby in the back [of the house], no food, no heart, no immunisation…’ Luthando FGD 1

Informants explained that discussion about sex and family planning was uncommon in Swati culture. Couples, especially unmarried, did not discuss family planning and there were misconceptions about contraception that limited women’s use of it, resulting in unplanned pregnancy.

‘It is possible to plan the pregnancy if you are married. You can discuss that with your partner. But if you are not married, that’s not possible, because you cannot expect anybody to discuss about pregnancy with a boyfriend.’ Aviwe FGD 3

Furthermore, informants voiced that pregnancies were often not a conscious decision and individuals and couples may not have formulated intentions about reproduction prior to a pregnancy occurring:

‘I don’t think they have ever asked themselves “how many children do I want?”’ Luthando FGD 1

Informants further stated that parents do not talk to their children about sex because it is against cultural norms. Sometimes parents used myths to describe where babies come from, such as being dropped by an airplane, to avoid ‘sex talk’. Simply talking about relationships and emotions between boys and girls was perceived as a taboo in local culture:

‘Here in Swaziland we don’t talk about it even at home. Even I can say we do have crushes at grade 1, “Yeah, I like this guy”, but how can I tell my mum that I like him at school? She will say, “Hey you I will beat you! Don’t talk about this, you will be a bitch”, you know, this [sort of] thing.’ Sakhile FGD 2

The above mentioned confines of Swati norms affect teenagers’ reproductive life and health in particular: a vulnerable group who most often are unmarried, who are given few opportunities to gain own knowledge on sex and who often lack financial resources, making them easy prey to older men.

Transactional relationships

Informants described how vulnerable women entered into sexual relationships for transactional benefits. These transactions took several forms and provided teenagers with material things, such as mobile phones, in exchange for sex. After becoming pregnant, the teenagers were often left:

‘Usually, our experience is that most the unplanned pregnant are the teenagers. Because the teenagers felt trapped from those old men. And then after being pregnant they will leave them and then they will have to raise up the child alone, such that the child ends up being neglected, being left alone, not nourished because the mother does not know how to raise a child and she is still young and still wants to enjoy life.’ Luthando FGD 1

In other kinds of transactional relationships, the child might be used as a form of currency to force men to support the mother, particularly with respect to basic needs. Having children with different men was then beneficial, as that would raise more money for the woman and her offspring:

‘They [women] usually give birth to children of different fathers because they know that they will give them money for support’ Luthando FGD 1

Transactional sex and sex work were discussed by informants, who gave several reasons as to why women chose to sell sex for money. The main explanation was to maintain a living and to be able to pay bills. There was often one sex buyer for each type of commodity the woman needed. Having sex without a condom was common as buyers preferred it that way, and some paid double if no condom was used.

‘I can do sex-work at night, I can go for prostitution and come back with money and feed my children you know, while I have noticed the rule of relationship, I have money-men. When I stay in a one-room rented flat, maybe Babbe, maybe Mr. Dlamini is going to buy grocery our food. Maybe Mr. Schoka will pay the rent. Then others will pay water bills. That’s why it makes this unwanted pregnancy.’ Sakhile FGD 2

Exacerbating vulnerability and neglect

Several aspects of vulnerability and neglect were discussed. First, unplanned pregnancies may lead women to unsafe abortion procedures, as abortion laws in Eswatini are restrictive. Informants also discussed the neglect that occurred to children who were born from unplanned pregnancies. Some children were abandoned at the side of the road and informants believed parents did not love the child as much as they would have if the pregnancy had been planned. The importance of a mother’s love in particular, and the lack thereof in cases of unplanned pregnancy, was stressed by the informants in all three FGDs:

‘We understand that every child deserves love from both parents, the father and the mother. But if it is unplanned you may find that the child may end up not growing, not getting the love from the parents’ Aviwe FGD 3

‘It causes a lot of vulnerability to the children. They used to be vulnerable since in his father’s home he is not accepted. And, also, in her mothers’ home, he is still unaccepted. So, the children end up by being vulnerable.’ Simphiwe FGD 2

Mothers were often single parents raising their children on their own without enough resources to support them. This caused the children to grow up in an unhealthy home environment, with a lack of food, clothes and immunisation. Short birth spacing intervals further exacerbated the situation. Informants stressed how children from unplanned pregnancies could be psychologically affected by being neglected. Sometimes they ended up resenting their parents and looked for a means to escape, even if escaping entailed that leaving their home to live on the streets away from an abusive family setting.

‘Some people got anger towards their parents, how they were brought up, and the upbringing of the children. So, the anger can make you do anything, just to make the parents very hard. The anger makes you have to hatred and do the wrong things. You want attention, you need somebody that loves you. So, by doing that, obviously, if I’m doing something wrong, obviously I know what they will say: “Why are you doing that?”. [Because] they didn’t get love of their parents’ Smentelwe FGD 1

Overall, unplanned pregnancies were perceived as negative events with serious consequences for the children.

‘Once pregnant she accepts she is pregnant, but she won’t love the child. She won’t give the child the love that the child needs.’ Vuyokazi FGD 1

Multiple stressors and low self-esteem

The fifth and final sub-theme concerned how multiple stressors play a role in women’s reproductive decision making, or the absence of the same. Peer pressure was common among teenagers with low self-esteem and who want to fit in and make friends. Such teenagers may make decisions based on the groups they joined, even if this meant engaging in multiple sexual relationships and becoming pregnant:

‘The peer pressure it is really destroying our children. Because they know the facts and the consequences they are facing, but because of the current situation that she is in, she is definitely going to take a wrong decision.’ Busisiwe FGD 1

Informants described how some women perceived themselves to have limited self-value and disregarded their own well-being. Women who were looking for love and marriage could use pregnancy as a measure to achieve this, even if subjected to abuse.

‘I think unwanted pregnancies are because of these men or this birth right, being abusive to us [women]. Because you find that I’m pregnant, I’m not working. He is the one who is working. So I am expecting all my needs done by him. So, maybe one day he will not come back to me, you know, I will just stay because I want, I want his support. Even if he beats me, I’ll just stay because maybe I don’t have any place to go.’ Thandiwe FGD 2

Unplanned pregnancies were not infrequently caused by rape. How this affected the victim was discussed by several informants. According to one woman, the trauma of being subjected to sexual violence as a child sometimes led the victim to engage in sex with multiple partners later in life, as a way of reclaiming rights that had been violated. Sexual violence was often perpetrated by a relative, which was believed to affect the victim even more seriously since they were often not allowed to talk about it. Silence was demanded because of family ties or because the perpetrator was the breadwinner of the family.

‘There are some who are getting pregnant from relatives, because the child is being given money and the relative says “you mustn’t tell”. […] But it [the anger], it is eating the child, because she wants to speak up, [… but] she’s been threatened, “If you speak maybe I will kill you”’ Smentelwe FGD 1

Discussion

Study findings point to a complex and multi-layered picture of the underlying causes and implications of unplanned pregnancy in the studied settings in Eswatini. Findings emphasise the vulnerability of women, revealing a limited agency to plan and decide on their own reproduction in line with what has previously been reported from several sub-Saharan countries (Grilo et al. Citation2018; Harrington et al. Citation2016; Lewinsohn et al. Citation2018; Mkhwanazi Citation2010; Mkhwanazi Citation2014). The results also highlight the vulnerability of children from unplanned pregnancies who are being at risk of major health, social and psychological consequences. Being abandoned or not taken care of, not being given immunisation, clothes and enough food as well as not receiving education are imminent risks for children from unplanned pregnancies in this setting. Thus, children are deprived of their right to childhood care and development, with likely long-term consequences not only for themselves but also for the community and society they live in.

In line with findings from former studies (Pallitto, Campbell, and O'Campo Citation2005; Pallitto et al. Citation2013; Grace and Anderson Citation2018; Gee et al. Citation2009; Mkhwanazi Citation2014), we found that unplanned pregnancies were closely related to violence, both structural and gender-based. Structural violence includes social structures such as political and cultural conditions that prevent individuals from reaching their full potential and put them at harm (Farmer et al. Citation2006). Structural violence was illustrated in several ways, such as children being deprived of their early childhood care and development as described above, as well as by patriarchal norms and stereotypical gender roles. For example, gender roles influence women’s occupations, making them financially dependent on men, which in turn drive them to sell sex and give birth to unplanned children. At the same time, sex outside marriage is a cultural taboo. This illustrates a discrepancy between aspired to and lived cultural norms, which has earlier been described in this setting (Ruark et al. Citation2016; Fielding-Miller et al. Citation2016). In line with our findings, previous studies have identified poverty, food insecurity, as well as aspirations towards marriage as drivers for engaging in transactional sex in this setting (Fielding-Miller et al. Citation2014; Fielding-Miller et al. Citation2016). Gender-based violence in this study was exemplified by direct physical abuse, as well as rape and incest, which have been reported to be common in Eswatini (Reza et al. Citation2009; Fielding-Miller et al. Citation2019; Ruark et al. Citation2016).

A deeper understanding and targeting of these structures is needed if unwanted pregnancies are to be prevented. Social-ecological models are widely used within global public health and have been proposed as a framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of social issues including violence (Krug et al. Citation2002). These models point to often complex interactions and inter-dependence between different layers, from individual and relationship to community and societal factors (Krug et al. Citation2002; Glanz, Rimer, and Viswanath Citation2015). Our results fit well with such frameworks.

At the individual level, informants described how low self-esteem and being exposed to peer pressure encouraged unplanned pregnancy and how these factors were closely linked to the inter-personal family relationships characterised by vulnerability and previous neglect (). At the relationship level, a strong driver for unplanned pregnancy was a setting in which many relationships between partners was described as transactional. Pregnancy was considered something that carried value for the woman, sometimes not as a source of offspring but rather as leverage in future negotiations. This is in turn driven by community conditions, described by the informants as ‘a life less privileged’, in which poverty, unemployment and lack of education were common. These conditions encourage an opportunistic approach to everyday survival, in which sexual intercourse is one of the few assets women have. These interactions between the individual and relationship levels, as well as between the community and societal levels, are framed within a society and culture characterised by strong patriarchal norms, further exacerbating and solidifying the structures driving the cycle of unplanned pregnancy across generations.

Interventions aimed at reducing the number of unplanned or unwanted pregnancies need to acknowledge all levels of the social-ecological model. As single intervention approaches cannot hope to be successful, strategic programming and collaborations between interventions at different levels are needed (Jewkes, Flood, and Lang Citation2015). To address the individual factors identified in this study, empowering young women is essential. In two randomised control trials from sub-Saharan Africa (Kapiga et al. Citation2019; Pronyk et al. Citation2006), combining social empowerment interventions with economic empowerment through microfinance reduced women’s experience of intimate partner violence. The combined interventions were more effective than microfinance alone, emphasising the importance of social empowerment (Kapiga et al. Citation2019). Based on our findings, the Philani mentor mother model being implemented by Siphilile, offers promise as it emphasises empowerment and gender awareness. It also supports behaviour change and encourages health in multiple ways (le Roux et al. Citation2013; Målqvist Citation2019). Treating men as allies of women in preventing violence is also crucial (Jewkes, Flood, and Lang Citation2015). In the Stepping Stones intervention in South Africa, both women and men were supported to build gender equitable relationships and the intervention succeeded in reducing intimate partner violence across two years of follow-up (Jewkes et al. Citation2008).

Strengthening women’s and children’s rights is essential to reducing violence and unwanted pregnancy. The Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence Bill was first introduced in the Swati parliament in 2009 (Amnesty International Citation2018). The law finally passed in 2018, criminalising incest, marital rape and increasing the age of sexual consent to 18 years (Southern Africa Litigation Centre Citation2019). However, effective implementation of the law remains to be achieved, as well as the strengthening of other rights, such as pregnant young women’s opportunity to attend school and allowing women to sterilise without the consent of a male family member. Finally, sensitising individuals, families and communities to the importance of rights for all is key.

Methodological considerations and reflexivity

Mentor mothers are key informants about unplanned pregnancy as they encounter it every day when meeting with clients. As peer supporters, they also bring the perspective of being Swazi women, having faced similar challenges as their clients. For example, seven out of ten informants reported having had an unplanned pregnancy themselves.

Sensitive and personal experiences and perceptions were shared during the FGDs. Discussions were often lively and deviant cases presented and debated. The first two FGDs provided particularly rich data. Our results display a range of perspectives including non-normative perceptions of unplanned pregnancies in this setting. Having said this, individual interviews with mentor mothers could have added credibility to the findings as there may have been sensitive issues not talked about in the discussions. In addition, not including Swati men as informants is a limitation and we suggest future studies do so. An increased understanding of men’s perceptions of unplanned pregnancies and how they are affected by the gender norms identified in this study is needed.

People with different backgrounds and knowledge about the context participated in the analysis. This triangulation enabled the sharing of a wide range of perspectives. JNH is a female medical doctor and doctoral student from Sweden. She has earlier conducted quantitative research with Siphilile, identifying high rates of unplanned pregnancies. JNH had joined the mentor mothers in their fieldwork and held training sessions in family planning and knew most of them. Returning with an intervention aiming to improve family planning probably increased the mentor mothers’ trust in JNH and positively impacted the discussions. KA is a medical doctor from Sudan with experience of sexual and reproductive health in other African contexts and of qualitative research methodology. TT is a nurse-midwife with a special research focus on pregnancy planning. MJ is a Swedish medical doctor and senior consultant in gynaecology and obstetrics. MM is a Swedish medical doctor and the former Executive Director of Siphilile. He had lived and conducted health research in Eswatini for several years and had a prolonged engagement with the organisation. Finally, NM is a nurse-midwife from Eswatini and the current Executive Director of Siphilile. Her role in validating the results was crucial as she had many years’ experience working with family planning in this setting.

Conclusion

This study adds depth to understanding of the underlying causes and implications of unplanned pregnancy for women and children in socially and economically disadvantaged settings in Eswatini. In this context, individual factors such as perceived low self-esteem as well as poor community conditions drove young women to engage in transactional relationships characterised by abuse, gender inequality and unsafe sexual practices, often resulting in unplanned pregnancy. These pregnancies led to neglect and abandonment of children, enhancing the likelihood that they too would grow up to become vulnerable young adults at risk of unplanned pregnancy, thereby creating a perpetuating cycle of unplanned childbearing. In order to break this vicious cycle in which women’s and children’s health and rights are compromised, multi-level interventions aimed at strengthening the social position and rights of women and children are needed.

Disclosure statement

Nokuthula Maseko is the current and Mats Målqvist the former Executive Director of Siphilile Maternal and Child Health.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amnesty International. 2018. “Report 2017/18, The State of the World’s Human Rights.” London. Accessed 29 June 2020. https://www.amnesty.org/download/Documents/POL1067002018ENGLISH.PDF

- Amo-Adjei, J., and D. Anamaale Tuoyire. 2016. “Effects of Planned, Mistimed and Unwanted Pregnancies on the Use of Prenatal Health Services in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multicountry Analysis of Demographic and Health Survey Data.” Tropical Medicine & International Health: TM & IH 21 (12): 1552–1561.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Brown, S. S., and L. Eisenberg. 1995. The Best Intentions: Unintended Pregnancy and the Well-Being of Children and Families. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Unintended Pregnancy. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

- Central Statistical Office (CSO) [Swaziland], and Macro International Inc. 2008. Swaziland Demographic and Health Survey 2006-07. Mbabane, Swaziland: Central Statistical Office and Macro International Inc.

- Central Statistical Office and UNICEF. 2016. Swaziland Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2014. Final Report. Mbabane, Swaziland: Central Statistical Office and UNICEF.

- Cheng, D., E. B. Schwarz, E. Douglas, and I. Horon. 2009. “Unintended Pregnancy and Associated Maternal Preconception, Prenatal and Postpartum Behaviors.” Contraception 79 (3): 194–198.

- Farmer, P. E., B. Nizeye, S. Stulac, and S. Keshavjee. 2006. “Structural Violence and Clinical Medicine.” PLoS Medicine 3 (10): e449.

- Fielding-Miller, R., K. L. Dunkle, N. Jama-Shai, M. Windle, C. Hadley, and H. L. Cooper. 2016. “The Feminine Ideal and Transactional Sex: Navigating Respectability and Risk in Swaziland.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 158: 24–33.

- Fielding-Miller, R., Z. Mnisi, D. Adams, S. Baral, and C. Kennedy. 2014. ““There Is Hunger in My Community”: A Qualitative Study of Food Security as a Cyclical Force in Sex Work in Swaziland.” BMC Public Health 14: 79.

- Fielding-Miller, R., F. Shabalala, S. Masuku, and A. Raj. 2019. “Epidemiology of Campus Sexual Assault among University Women in Eswatini.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519888208

- Gee, R. E., N. Mitra, F. Wan, D. E. Chavkin, and J. A. Long. 2009. “Power over Parity: Intimate Partner Violence and Issues of Fertility Control.” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology 201 (2): 148.e1–e7.

- Gipson, J. D., M. A. Koenig, and M. J. Hindin. 2008. “The Effects of Unintended Pregnancy on Infant, Child, and Parental Health: A Review of the Literature.” Studies in Family Planning 39 (1): 18–38.

- Glanz, K., B. K. Rimer, and K. Viswanath. 2015. “Ecological Models of Health Behavior.” Chapter 3 in Health Behavior: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by K. Glanz, B. K. Rimer, and K. Viswanath, 43–64. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Grace, K. T., and J. C. Anderson. 2018. “Reproductive Coercion: A Systematic Review.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 19 (4): 371–390.

- Grilo, S. A., M. Catallozzi, C. J. Heck, S. Mathur, N. Nakyanjo, and J. S. Santelli. 2018. “Couple Perspectives on Unintended Pregnancy in an Area with High HIV Prevalence: A Qualitative Analysis in Rakai, Uganda.” Global Public Health 13 (8): 1114–1125.

- Hall, J. A., G. Barrett, T. Phiri, A. Copas, A. Malata, and J. Stephenson. 2016. “Prevalence and Determinants of Unintended Pregnancy in Mchinji District, Malawi; Using a Conceptual Hierarchy to Inform Analysis.” PLoS One 11 (10): e0165621.

- Harrington, E. K., S. Dworkin, M. Withers, M. Onono, Z. Kwena, and S. J. Newmann. 2016. “Gendered Power Dynamics and Women's Negotiation of Family Planning in a High HIV Prevalence Setting: A Qualitative Study of Couples in Western Kenya.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 18 (4): 453–469.

- Iyun, V., K. Brittain, T. K. Phillips, S. Le Roux, J. A. McIntyre, A. Zerbe, G. Petro, E. J. Abrams, and L. Myer. 2018. “Prevalence and Determinants of Unplanned Pregnancy in HIV-Positive and HIV-Negative Pregnant Women in Cape Town, South Africa: A Cross-Sectional Study.” BMJ Open 8 (4): e019979.

- Jewkes, R., M. Flood, and J. Lang. 2015. “From Work with Men and Boys to Changes of Social Norms and Reduction of Inequities in Gender Relations: A Conceptual Shift in Prevention of Violence against Women and Girls.” The Lancet 385 (9977): 1580–1589.

- Jewkes, R., M. Nduna, J. Levin, N. Jama, K. Dunkle, A. Puren, and N. Duvvury. 2008. “Impact of Stepping Stones on Incidence of HIV and HSV-2 and Sexual Behaviour in Rural South Africa: Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 337: a506.

- Kapiga, S., S. Harvey, G. Mshana, C. H. Hansen, G. J. Mtolela, F. Madaha, R. Hashim, et al. 2019. “A Social Empowerment Intervention to Prevent Intimate Partner Violence against Women in a Microfinance Scheme in Tanzania: Findings from the MAISHA Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial.” The Lancet Global Health 7 (10): e1423–e34.

- Kavanaugh, M. L., K. Kost, L. Frohwirth, I. Maddow-Zimet, and V. Gor. 2017. “Parents' Experience of Unintended Childbearing: A Qualitative Study of Factors That Mitigate or Exacerbate Effects.” Social Science & Medicine (1982) 174: 133–141.

- Kost, K., and L. Lindberg. 2015. “Pregnancy Intentions, Maternal Behaviors, and Infant Health: Investigating Relationships with New Measures and Propensity Score Analysis.” Demography 52 (1): 83–111.

- Krug, E. G., L. L. Dahlberg, J. A. Mercy, A. B. Zwi, and R. Lozano, eds. 2002. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Le Roux, I. M., M. Tomlinson, J. M. Harwood, M. J. O'Connor, C. M. Worthman, N. Mbewu, J. Stewart, et al. 2013. “Outcomes of Home Visits for Pregnant Mothers and Their Infants: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial.” AIDS (London, England) 27 (9): 1461–1471.

- Levandowski, B. A., L. Kalilani-Phiri, F. Kachale, P. Awah, G. Kangaude, and C. Mhango. 2012. “Investigating Social Consequences of Unwanted Pregnancy and Unsafe Abortion in Malawi: The Role of Stigma.” International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 118 (Suppl 2): S167–S71.

- Lewinsohn, R., T. Crankshaw, M. Tomlinson, A. Gibbs, L. Butler, and J. Smit. 2018. “This Baby Came Up and Then He Said, “I Give Up!”: The Interplay between Unintended Pregnancy, Sexual Partnership Dynamics and Social Support and the Impact on Women's Well-Being in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa.” Midwifery 62: 29–35.

- Målqvist, M. 2019. Proud to Be a Siphilile Woman! Mission from the Margins. Stockholm: Books on Demand.

- Marston, C., and J. Cleland. 2003. “Do Unintended Pregnancies Carried to Term Lead to Adverse Outcomes for Mother and Child? An Assessment in Five Developing Countries.” Population Studies 57 (1): 77–93.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2014. “Fundamentals of Qualitative Data Analysis.” Chap 4 in Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousands Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Mkhwanazi, N. 2010. “Understanding Teenage Pregnancy in a Post-Apartheid South African Township.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 12 (4): 347–358.

- Mkhwanazi, N. 2014. “Revisiting the Dynamics of Early Childbearing in South African Townships.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 16 (9): 1084–1096.

- Niemeyer Hultstrand, J., T. Tydén, M. Jonsson, and M. Målqvist. 2019. “Contraception Use and Unplanned Pregnancies in a Peri-Urban Area of Eswatini (Swaziland).” Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Official Journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives 20: 1–6.

- Pallitto, C. C., J. C. Campbell, and P. O'Campo. 2005. “Is Intimate Partner Violence Associated with Unintended Pregnancy? A Review of the Literature.” Trauma, Violence & Abuse 6 (3): 217–235.

- Pallitto, C. C., C. Garcia-Moreno, H. A. Jansen, L. Heise, M. Ellsberg, and C. Watts. 2013. “Intimate Partner Violence, Abortion, and Unintended Pregnancy: Results from the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women's Health and Domestic Violence.” International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 120 (1): 3–9.

- Powell, R. A., and H. M. Single. 1996. “Focus Groups.” International Journal for Quality in Health Care : Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care 8 (5): 499–504.

- Pronyk, P. M., J. R. Hargreaves, J. C. Kim, L. A. Morison, G. Phetla, C. Watts, J. Busza, and J. D. Porter. 2006. “Effect of a Structural Intervention for the Prevention of Intimate-Partner Violence and HIV in Rural South Africa: A Cluster Randomised Trial.” The Lancet 368 (9551): 1973–1983.

- Reza, A., M. J. Breiding, J. Gulaid, J. A. Mercy, C. Blanton, Z. Mthethwa, S. Bamrah, L. L. Dahlberg, and M. Anderson. 2009. “Sexual Violence and Its Health Consequences for Female Children in Swaziland: A Cluster Survey Study.” The Lancet 373 (9679): 1966–1972. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60247-6

- Ruark, A., C. E. Kennedy, N. Mazibuko, L. Dlamini, A. Nunn, E. C. Green, and P. J. Surkan. 2016. “From First Love to Marriage and Maturity: A Life-Course Perspective on HIV Risk among Young Swazi Adults.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 18 (7): 812–825.

- Santelli, J., R. Rochat, K. Hatfield-Timajchy, B. C. Gilbert, K. Curtis, R. Cabral, J. S. Hirsch, and L. Schieve. 2003. “The Measurement and Meaning of Unintended Pregnancy.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 35 (2): 94–101.

- Sedgh, G., S. Singh, and R. Hussain. 2014. “Intended and Unintended Pregnancies Worldwide in 2012 and Recent Trends.” Studies in Family Planning 45 (3): 301–314.

- Southern Africa Litigation Centre, COSPE Onlus and Foundation for Socio-Economic Justice. 2019. A Summary of Eswatini’s Sexual Offences and Domestic Violence Act. Johannesburg: Southern Africa Litigation Centre.

- Tsui, A. O., R. McDonald-Mosley, and A. E. Burke. 2010. “Family Planning and the Burden of Unintended Pregnancies.” Epidemiologic Reviews 32 (1): 152–174.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2019. “Gender Inequality Index.” Accessed 30 December 2019. http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/68606

- Van Lith, L. M., M. Yahner, and L. Bakamjian. 2013. “Women's Growing Desire to Limit Births in Sub-Saharan Africa: Meeting the Challenge.” Global Health, Science and Practice 1 (1): 97–107.