Abstract

Child marriage is associated with adverse health and social outcomes for women and girls. Among pastoralists in Kenya, child marriage is believed to be higher compared to the national average. This paper explores how social norms and contextual factors sustain child marriage in communities living in conflict-affected North Eastern Kenya. In-depth interviews were carried out with nomadic and semi-nomadic women and men of reproductive age in Wajir and Mandera counties. Participants were purposively sampled across a range of age groups and community types. Interviews were analysed thematically and guided by a social norms approach. We found changes in the way young couples meet and evidence for negative perceptions of child marriage due to its impact on the girls’ reproductive health and gender inequality. Despite this, child marriage was common amongst nomadic and semi-nomadic women. Two overarching themes explained child marriage practices: 1) gender norms, and 2) desire for large family size. Our findings complement the global literature, while contributing perspectives of pastoralist groups. Contextual factors of poverty, traditional pastoral lifestyles and limited formal education opportunities for girls, supported large family norms and gender norms that encouraged and sustained child marriage.

Introduction

Child marriage, defined as the marriage of a girl or boy before the age of 18 years, disproportionately affects girls (UNICEF Citation2019). Globally, the highest levels of child marriage are found in sub-Saharan Africa, where an estimated 35% of young women were first married before the age of 18. Child marriage is illegal in Kenya (National Council for Law Reporting Kenya Citation2010), yet remains a common experience for nomadic pastoralist girls. The risk factors, including rural residence, low levels of education, low socioeconomic status and high prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), are all characteristics of pastoralist communities living in North Eastern Kenya (Nyamongo Citation2000; Kipuri and Ridgewell Citation2008; Zakaria Maro et al. Citation2012; Rumble et al. Citation2018).

The counties of Mandera and Wajir represent some of the most resource-deprived counties in Kenya, with high levels of child marriage and its associated negative reproductive health outcomes (IRIS Citation2015; MoALF Citation2018, Citation2017; African Institute for Development Policy Citation2017b, Citation2017a). These counties have an ethnically Somali and religiously Muslim population, where the majority are nomadic (and semi-nomadic) pastoralists. These populations live in rural areas with varying degrees of sedentarism, with little access to health services and formal education (Zakaria Maro et al. Citation2012).

Data from 2015 show the median age at first marriage among women aged 25–49 in Wajir (18 years) and Mandera (19 years) is lower than the national average (20 years) (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF International Citation2015). Unequal opportunities in terms of education and employment mean that girls marry younger than boys (Nyamongo Citation2000), and many marriages in this context are arranged (Khalif Citation2010). Figures for child marriage and adolescent childbearing are likely to be higher amongst nomadic populations as census data generally provides estimates for urban populations.

Research on child marriage has become increasingly important, as it is considered a major public health concern and human rights violation (Nour Citation2009). Its prominence on the global agenda is demonstrated by its inclusion in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), with the target to eradicate child marriage entirely by 2030 (United Nations Citation2015). Girls who marry as children are at greater risk of experiencing maternal mortality and morbidity through early childbearing and grand multiparity, acquiring sexually transmitted infections, experiencing intimate partner violence, and poor mental health (Ellis Simonsen et al. Citation2005; Walker Citation2012; Petroni et al. Citation2017). In Wajir and Mandera, the birth rate among young women aged 15–19 years is higher than the national average – more than 1 in 10 babies is born to a girl aged 15–19 years and the total fertility rate is 7.8 and 5.2 respectively (African Institute for Development Policy Citation2017a, Citation2017b). In many contexts, including in Kenya, child marriage and teenage pregnancy are associated with limited educational and economic opportunities for girls (Steinhaus et al. Citation2016; Wodon et al. Citation2017), which could also be the case amongst pastoralist communities.

It is important to take account of local understandings of child marriage. A small body of literature provides an alternative to the dominant narrative portrayed by the international development sector that child marriage is forced, and girls lack autonomy. In areas of Kenya and Tanzania, child marriage has prevented the negative health and social consequences of premarital sex and childbearing (Mtengeti et al. Citation2008; Archambault Citation2011; Stark Citation2018a). In some contexts, girls take an active role in marital decision making (Schaffnit, Urassa, and Lawson Citation2019). For the Maasai, another pastoralist society in Kenya, marriage unites families and increases access to resources in the face of increasing economic hardship (Archambault Citation2011). These perspectives offer nuance to current dominant discourse, without detracting from the potential harms of child marriage. They highlight the importance of understanding local attitudes, including social norms, to improve outcomes for women and girls.

Social norms theory is one approach to exploring why harmful gender-based practices persist, including child marriage (Shell-Duncan et al. Citation2018; Cislaghi et al. Citation2019; Steinhaus et al. Citation2019). Social norms are informal rules that govern what is acceptable behaviour within a given context (Mackie et al. Citation2015). Cialdini defines two types of social norms: ‘descriptive norms’ (beliefs about what other people do) and ‘injunctive’ norms (beliefs about whether others will approve of a behaviour) (Cialdini et al. Citation2006). Norms exist within a reference group and are upheld by a network of reciprocal expectations of relevant others (Mackie et al. Citation2015), including older relatives and community and religious leaders (Jones et al. Citation2014). They are reinforced and maintained by social influence, where non-compliance results in negative sanctions (Mackie et al. Citation2015; Cislaghi, Manji, and Heise Citation2018). Importantly, norms do not exist in a vacuum but are influenced by material, individual and social domains (Cislaghi and Heise Citation2019).

Gender norms assign rules and behaviours based on gender (Marcus et al. Citation2015). In Kenya, inequitable gender norms that assign women and girls household responsibilities contribute to child marriage (Steinhaus et al. Citation2016). Norms around girls’ sexuality and chastity, for example, contribute to the practice and young girls are expected to be virgins when they marry (Boyden, Pankhurst, and Tafere Citation2013; Adamu et al. Citation2017; Cislaghi et al. Citation2019).

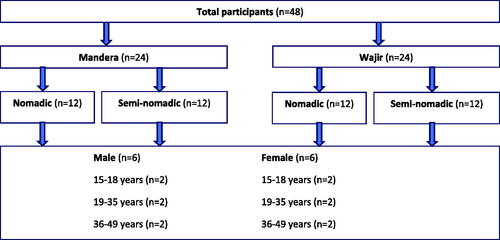

There is a dearth of literature that explores child marriage amongst pastoralist populations. This study forms part of a larger qualitative study with 203 participants across focus group discussions (n = 16), key informant interviews (including village and religious leaders and health providers) (n = 12), qualitative social network interviews (n = 23), and individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) (n = 48). The overall study explores reproductive and sexual health, including marriage practices, family planning, and fertility desires amongst nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralists in North Eastern Kenya. For this study, we analysed the 48 IDIs. We examined data pertaining to marriage practices with the aim to identify: 1) gender norms that influence child marriage; and 2) contextual factors (material, individual, and social factors) associated with child marriage that may be unique to the realities of pastoralist populations.

Methods

Study site and participants

Participants in the study were nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralist men and women (n = 48) living in Wajir and Mandera counties, North Eastern Kenya (see ). In these arid and semi-arid areas, the population is largely made up of nomadic or semi-nomadic Somali pastoralists (UNFPA 2015; Republic of Kenya Citation2017; Scharrer Citation2018). The area is characterised by poverty, marginalisation, periods of insecurity and inter-communal conflicts, often as a result of disputes over pasture, especially during the dry season (IRIS Citation2015; Lind Citation2018).

Pastoralist communities predominantly rely on livestock for their livelihoods, with varying degrees of mobility (Krätli, Swift, and Powell Citation2014; Fitzgibbon Citation2012). Following discussion with our research partner Save the Children International Kenya, we defined nomadic pastoralists as those that rely on camel and goats for their livelihoods, migrating in search of pasture and water. Semi-nomadic groups herd cattle and/or goats and settle for longer periods.

Study sites were identified by Save the Children International Kenya, who have provided services in Wajir and Mandera and were aware of pastoralist settlements and movements at the time of data collection. From each county, one nomadic and one semi-nomadic community was chosen to explore potential differences between community types. Sites were chosen based on their accessibility at the time of data collection (there was ongoing conflict in some areas). Semi-nomadic communities lived in semi-permanent structures, located close to roads and towns. One community had resettled in the last three months following conflict with a neighbouring clan, while the other had lived in their area for 12 years. Nomadic sites were harder to reach. Communities had either recently moved (two months prior) or were moving to new grazing land soon. Both community types used mobile phones. Community leaders from semi-nomadic study sites described they had little interaction with international, governmental, or local organisations, possibly explaining their positive engagement with the research team.

Participants were recruited to reflect an even spread of ages (15−18, 19−35, and 36−49 years) based on community definitions of life stages (younger, middle-aged and older). Unmarried girls and boys aged 15–18 years were also sampled. Male community leaders and/or elders were the gatekeepers to the community; they mobilised men and women present at the time of data collection to recruit participants. Male community members recruited men, while female community members recruited women. These were all individuals who were nearby at the time of data collection.

Study design and tools

Semi-structured IDIs were carried out with 48 participants. IDIs allowed us to gather detailed information, especially in a context where child marriage is a sensitive topic (Johnson Citation2001). Interview guides included questions on four themes: family formation, family size, family planning methods and the impact of conflict on reproductive health. Data on child marriage in this paper emerged from the themes on family formation and family size. To investigate the universe of norms (beliefs about what others do and approve of) related to child marriage, participants were asked about: 1) their attitudes towards marriage-related practices, and 2) what was typical and appropriate. Following recommendations in the literature on social norms (Cislaghi and Heise Citation2017; CARE Citation2017), we included vignettes to create opportunities for participants to share examples of how norms affected marriage practices (see ). Demographic information was collected during the interview.

Table 1. Example vignette to explore marriage practices.

Data collection & ethical considerations

The interviews took place in November 2018. Interviewers from Wajir and Mandera spoke Borana, Somali and English. Interview guides were translated into relevant local languages. Interviewers received a one-week training in the ethics of conducting qualitative research and social norms theory, during which interview guides, including vignettes, were piloted and translations amended. To conduct IDIs, the research team spent a full day at each study site. Participants were provided with background information, before giving their oral consent to participate and be audio recorded. Only one interview with a young woman was stopped early as the participant found the questions difficult to answer. Interviews were transcribed and translated into English by native Somali and Borana speakers. Transcripts were chosen randomly to be quality checked by a member of the research team, fluent in both local languages and English. This study received ethical approval from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (Ref: 16109) and the Africa Medical and Research Foundation in Kenya (Ref: AMREF-ESRC P542/2018) in 2018.

Data analysis

Initially, the first author (HL) read through the 48 transcripts, noting recurring themes and differences across interviews. Sections of the IDIs relevant to the objectives of this study (family formation and size), were moved to NVivo 12, where they were classified by age, gender, and community type (nomadic or semi-nomadic). This allowed for a comparison of the resulting themes by demographic characteristics.

Next, we coded the data, using inductive and deductive approaches in tandem so as not to limit the exploration of novel findings whilst using available literature to guide how we created and applied codes. The first author (HL) created codes until saturation was reached. This was followed by refinement. Codes deemed irrelevant were removed and similar codes were merged. Finally, the authors organised the codes into themes, drawing upon Braun and Clarke’s six phases of Qualitative Analysis Framework (2006), being mindful to include contradictory data where it appeared.

The final codebook contained 26 codes, which were cross-checked by the first (HL) and second author (LK). provides examples of how codes were grouped to form five themes discussed in this paper: 1) marital age and partner formation, 2) respectable women marry early, 3) girls should refrain from premarital sex, 4) women should give birth to many children and 5) support for later marriage.

Table 2. Examples of themes that emerged in the data and their corresponding codes.

Findings

Child marriage was more common among women and girls than men and boys (see ). The majority of women were married between 15 and 18 years, whereas men commonly married between 19 and 24 years. Eight participants were not married and did not have children. Among the participants in the study who had children, half had more than six (younger participants had not finished childbearing and had fewer children). Some men in this study had multiple wives and, as such, had more children than women had (more than 11 in some instances).

Table 3. Participant characteristics.

Marital age and partner formation

Men had married later than women, and participants explained that this was typical. In response to a vignette asking at what age a couple from their community married, most participants agreed that a man would marry at 20 or older, while a woman was expected to marry before 18. This was seen in responses such as 'He is 20 years' and 'She is 16 years' when participants referred to the typical ages of marriage.

To understand the power dynamics embedded in relationships around the time of marriage, we asked participants how couples met. They described two possible ways. Firstly, a small number of participants said marriages were arranged by parents, with either the girl or both spouses being pushed or forced to marry. It was mostly participants from nomadic communities that described this kind of meeting. An older woman from a nomadic community said: 'The father of the girl receives money from another family and gives his girl away, there is no courtship, that's exactly what happened to me, they just put me and him together in a hut.' A younger nomadic woman provided evidence that the practice was still happening, when she said: 'Some [couples] are forced into a house together by a relative.'

Other participants described how more recently couples met spontaneously – whilst working the land, herding or at school. In these cases, parents would typically be informed after the couple themselves had decided to get married. A smaller number of participants described how couples might elope without seeking parental approval. All participants reported this new, more spontaneous, way of meeting partners. An older man from a nomadic community said: 'During our times, the parents would bring them together, but today those who have gone to school find each other. Once a man has won a woman’s acceptance, they inform their parents.'

Semi-nomadic participants reported similar trends; an older woman said: '[A] long time ago [young people] who took care of goats, unaware of anything, would be married off. Nowadays they exchange phone numbers, talk and after they come to an agreement, they get married.'

Women and men described how the meeting of marriage partners was facilitated by increased access to mobile phones. Young couples could communicate without their parent’s involvement. This was particularly true for participants from semi-nomadic communities: 'They communicate through the phone, get to know each other and then get married,' said a young woman; 'They will use phone and Internet to know each other and relatives can also introduce them to each other' said an older man.

Despite new ways of meeting, parents (and close relatives) remained gatekeepers to formalising marriage in both semi-nomadic and nomadic communities. As two older women described: 'A friend may take the phone number and exchange this with the man, then they seduce each other and when they fall in love they go to their parents for marriage' (semi-nomadic) and, '[The couple] seduce each other and after they agree [to marry] they tell their parents that he got a woman and his parents will ask the lady’s parents for her hand in marriage' (nomadic community). This belief that couples typically seek parental approval before marrying was also held by younger participants: 'They just go the parents of the lady and ask for hand in marriage' said a young woman from a semi-nomadic community.

Gender norms sustaining child marriage

From the themes apparent in the IDIs, three gender norms sustained child marriage: 1) girls were expected to marry early; 2) girls were expected to be virgins before marriage; and 3) women should bear many children.

Respectable women marry early

When asked when women should marry, puberty, menarche and maturity were frequently mentioned as markers. A young woman linked the perfect age to maturity: '[best age to marry is 16], that’s when girls are grown, and it is time for marriage'. An older women from a nomadic community linked menarche and marriage when she said: 'They just wait until you start your menses and then you’re married off'.

The interviews revealed limited roles for pastoralist women outside of marriage and childbearing/rearing. Some participants described how women had 'nothing else to do' other than get married and have children. A middle-aged female from a semi-nomadic community commented: '[S]he needs to start her family and be busy with her children'. Child marriage facilitated girls to fulfil their prescribed gender roles.

We found evidence of a descriptive norm of child marriage for girls among both men and women: participants considered it to be extremely common and some said they did not know of any women who had married past 18. A middle-aged man and woman (semi-nomadic) said, respectively: '[T]hey [women who marry later] are not here in this community' and, '[A]ll of them get married early.' A young woman (nomadic) also described this: 'I have never seen anyone who got married late; the oldest I have seen is a girl who got married at the age of 18.'

We also found evidence of an injunctive norm in the form of women who married after 18 years being stigmatised. One younger semi-nomadic woman said of women who married late: 'Some people will say it is because of [the woman’s] bad character that they did not get married while young.' A younger nomadic man expressed a similar view: 'People say a lot of things, but the girl is a difficult person, it could also be that she is sickly'. Participants frequently used the word guumays' (a derogatory term for single women who are beyond the conventional age for marriage) to describe women who married late. Men who married older women were also stigmatised: 'Men are teased when they marry an old aged woman. He is told he is married to a guumays' said a middle-aged nomadic man. However, a small number of participants attributed late marriage to calaf (fate or luck) and the will of God – participants said there was little they could do, or say, to help these women.

The stigma surrounding marrying past the typical age for women in these communities influenced decisions to marry early. Whilst unmarried women and girls were stigmatised for not marrying before the age of 18, their families and partners also experienced negative social sanctions. Here, gender norms applied to both women and their families.

Girls should refrain from premarital sex

Girls were expected to be virgins before marriage. Participants believed that sex should only take place within marriage. Marriage soon after puberty protected girls and their families from the shame of premarital sex. An older man (nomadic) and a middle-aged man (semi-nomadic) referred to purity as a quality for brides: 'When she is young, she is pure and a virgin, but if she's older she will have had several men' and: 'It’s good she gets married when she is pure and before she gets old and starts moving around with men'.

Closely connected to the shame of premarital sex was the worry that girls might get pregnant out of wedlock, with participants anticipating negative sanctions for both the girl and her family: 'The parents are afraid that [girls] might get pregnant out of wedlock and embarrass the family. That’s why they are married off at a younger age.' That families were anticipating shame for their daughters’ behaviour is critical in understanding the strategies they put in place to accept, facilitate or force her marriage.

Women should give birth to many children

Having many children was described as both typical and desirable. Participants described women had between 8 and 12 children, a descriptive norm for large families. A young woman (semi-nomadic) said women: 'Give birth to up to 10 children', and an older man (nomadic) said: 'Most have 9′. We also found evidence for an injunctive norm: having many children increased social standing. For example, a middle-aged woman (semi-nomadic) said: 'People will recognise you when you have more children’. Women with few children faced stigma, teasing and gossip from other community members; a young woman (nomadic) said a woman who had few children 'has wasted her time, she is a guumays'.

In both community types, women were expected to marry early to begin childbearing. A young man (nomadic) said: '[Women who marry early] get children fast and can get many children when they are young, unlike a woman who is married at an older age and is running out of time'. Participants from semi-nomadic communities also acknowledged this: 'If she gets married when she is young, she will give birth to many kids.’

Having many children was important for men and women from both communities. Children helped with economic activities (for example, they worked the land). They also helped with household chores, such as washing and raising younger siblings. 'One will take care of animals, another one will go to Nairobi and work and earn a living, another one will help in taking care of the home, and others go to school and madrassa. But if you have only two then who can help you?' said an older woman (semi-nomadic). A few participants described high child mortality as a driver of high fertility. For example, a middle-aged woman (semi-nomadic) described that having many children was 'a gift from God. Others might die, and at least you will remain with some'. The desire for large families, partly motivated by the existing system of norms and partly held in place by material challenges, contributed to child marriage. Despite this normative and material context, some participants did express support for later marriage.

Support for later marriage

Generally, participants valued education and felt it was acceptable to delay marriage for it. One older woman worried about her daughter’s imminent marriage and its impact on her education if she stayed in her semi-nomadic community: 'My daughter is 15 years old and in standard seven. She has started her menstrual periods, and I am already worried for her. I sent her to [the city] so she can further her education there.'

Some participants said child marriage could lead to reproductive health 'complications' and 'difficulties' during pregnancy and childbirth. An older male (nomadic) described that, 'the one who gets married at 15 will have a difficult childbirth', while a middle-aged female (semi-nomadic) said: 'She's young and it might take a long time like 1 or 2 years before she gets pregnant because she has a weak uterus; recently [young married girls] are always taken to hospital because of pregnancy complications.'

A minority of participants voiced a personal desire to delay marriage; however, they felt this was not accepted in their community. Two older (nomadic) women voiced this concern: 'It’s good when they marry above 18 years, it’s just that [the community] are scared that they might get pregnant before marriage.' (semi-nomadic) and 'They arranged my daughter’s marriage this year, she is just 16, the grooms family said they will not wait any longer, but our family said she has not yet started her menses so they should wait.’

Discussion

Child marriage is a complex phenomenon, influenced by a range of normative and structural factors (Greene and Ellen 2019). Poverty, gender inequality and limited formal education, particularly for girls, all influence norms that encourage and sustain child marriage and high fertility (Zakaria Maro et al. Citation2012; Rumble et al. Citation2018). In this study, we found gender norms that support child marriage were held strongly by women, men, girls and boys. They encouraged the practice and imposed sanctions on those who did not. The importance of having many children also contributed to child marriage. Despite shifts in the way young couples met and the negative associations between child marriage and girls’ reproductive health and access to education, nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralist girls continued to marry young.

Marriage was common amongst girls in the study population – only two out of 24 women were married after 18. The percentage of women married before the age of 18 was higher than the national average for Kenya (DHS data indicates that 29% of 25–49-year-old women in Kenya married before 18) (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF International Citation2015). We expected that norms supporting child marriage would be more pervasive amongst older participants, reflecting downward national trends in Kenya and generational shifts in norms (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF International Citation2008, Citation2015). This was generally not the case, and participants of all ages adhered to norms in support of child marriage. We acknowledge however that while we use the term child marriage, cultural perspectives on childhood differ and girls who marry before 18 in this setting may not be seen culturally as 'children'. Many participants believed that girls were ready for marriage at the onset of menarche, rather than at a defined age threshold. They also described how many young girls participated in decisions about who they would marry. In using the term child marriage, we do not wish to detract from this agency, but rather we seek to recognise that nationally and internationally, those under 18 represent a protected population. This has implications for programming discussed later.

While we found evidence of new ways young couples met and married, this has not increased the typical age of marriage. Participants acknowledged that some couples decided to elope without parental approval. These ‘love marriages’ have been documented elsewhere as contributing to child marriage practices (McDougal et al. Citation2018; Kenny et al. Citation2019), and in this setting were linked with access to education and mobile phones for young people. Child marriage persisted as girls were married to prevent them from either eloping or transgressing gender norms and bringing shame to the family.

Gender norms sustained child marriage, similar to what has been identified in other low-and-middle-income contexts (Boyden, Pankhurst, and Tafere Citation2013; Kane et al. Citation2016; Adamu et al. Citation2017; Stark Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Cislaghi et al. Citation2019; Schaffnit, Urassa, and Lawson Citation2019). The fact that these gender norms applied to both women and their families can explain why families continue to marry their daughters early despite the potential harms identified by participants in this study (Cislaghi et al. Citation2019). Although some girls attended school, many could not expect to receive a formal education and participants described there was little for women to do outside of marriage. The pressure to marry early, coupled with limited educational and economic opportunities for women, are cited as reasons young girls drop out of school early (Wodon et al. Citation2017), while decreasing marriage trends have been associated with increased education opportunities for girls (Manda and Meyer Citation2005). Some participants in this study stated girls should delay marriage to further their education, yet it was difficult to deviate from the norm.

The desire for many children was particularly salient and influenced child marriage practices. While we anticipated this fertility preference would be associated with high maternal and child mortality, this emerged as a quieter theme in the interviews, likely due to a reluctance to discuss mortality in this context. Instead, we found that poverty, exacerbated by climate change, meant nomadic lifestyles were being abandoned and economies diversified. Having many children meant that tasks could be divided. Despite evidence of adolescent autonomy in marriage decision making, communities continued to make collectivist decisions, to increase access to resources and networks that benefit the household as a whole, which is common amongst pastoralists (Flintan Citation2008). Women were expected to bear many children early to fulfil their gender roles, but also to contribute to the economic stability of the family and community as a whole. With norms around family size held strongly, in addition to shifting realities, high fertility was a cause as well as a consequence of child marriage.

Limitations

The qualitative methodology used in this study has several limitations. Studying social norms is challenging, particularly in contexts where community norms conflict with global normative and legal structures against child marriage. As a result, social desirability may have affected participants’ answers to questions about the disadvantages of child marriage, particularly as this discourse only emerged when participants were asked directly. Limited probing and the sensitive nature of topics also meant some areas could not be explored in depth. Female genital mutilation/cutting, which is prevalent amongst these populations is associated with marriageability (UNFPA Citation2019), but was not explored due to its sensitive nature.

Prior to data collection, a number of steps were taken to minimise these limitations: we used vignettes to mitigate the challenges of measuring social norms, interviewers were from Wajir and Mandera and interview training was provided. Qualitative analysis is subject to the researcher's personal biases and preconceptions, influencing data analysis and presentation (Galdas Citation2017). To minimise the effects of this, the authors cross-checked codebooks and accounted for contradictions within the data, recognising that qualitative research is reflexive and subjective. The relatively large sample of 48 interviews ensured richness of data and representation.

Implications for future programmes

This paper contributes to the global literature on child marriage in two ways. First, it compliments what has been found in other contexts on gender norms and child marriage. Second, it provides insights into the underexplored perspective of pastoralist communities.

International policy and programmes rarely differentiate between (very) early, child and adolescent marriage. Instead, they call for an end to all child marriage (Yaya, Odusina, and Bishwajit Citation2019), often described as arranged, and/or forced (Efevbera Citation2019). Against this background, this paper offers some nuance on child marriage practices. Findings highlight the need for programmes to recognise and take account of young people’s agency (or their participation in decision-making), alongside structural and social pressure to marry.

Social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) is a method to change knowledge, beliefs, behaviours and harmful norms. SBCC strategies in this context should engage with the whole community to identify and address harmful norms, considering child marriage norms alongside norms on family size. Programmes should build on existing desires to delay marriage to design approaches that centre on the positive health and economic implications of later marriage for girls, women, their families and the wider community.

Finally, programmes need to consider broader contextual factors affecting child marriage practices, such as marginalisation, poverty and access to services. That child marriage persists, despite individual preferences to delay marriage, has important implications. The desire for large families is rooted in structural problems of poverty and economic vulnerability, further compounded by a lack of educational and economic opportunities for women outside of marriage. Without attention to these factors, programmes will be misaligned with the reality of the lives of communities in these settings and are unlikely to be impactful and sustainable.

Conclusion

Our findings show how gender and family size norms, alongside contextual factors of poverty and traditional pastoral lifestyles, sustain child marriage among nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralist communities in Kenya. Emerging realities and challenges, including livelihood diversification also contribute to the practice. In this setting, changing marital practices and the desire for large families are important in understanding why child marriage persists. However, there is evidence for personal preferences to delay marriage for girls, to improve reproductive health outcomes and access to education. Programmes should expand on existing narrow gender norms approaches to explore how locally held meanings and restrictive structures sustain child marriage.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the research participants who gave their time and shared their experiences. We also acknowledge the labour of the field interviewers who worked tirelessly, and at times in dangerous conditions, to collect data for this study. We acknowledge Save the Children International Kenya field staff members who contributed to data collection and interpretation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamu, H., A. Yusuf, K. Tunau, and M. Yahaya. 2017. “Perception and Factors Influencing Early Marriage in a Semi-Urban Community of Sokoto State, North-West Nigeria.” Annals of International Medical and Dental Research 2 (5):1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.21276/aimdr.2017.3.5.CM2

- African Institute for Development Policy. 2017a. “Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health: Mandera County. Fact Sheet.” https://www.afidep.org/download/fact-sheets/Mandera-County-fact-sheetF.pdf

- African Institute for Development Policy. 2017b. “Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health: Wajir County. Fact Sheet.” https://www.afidep.org/publication/reproductive-maternal-neonatal-and-child-health-wajir-county/

- Archambault, C. S. 2011. “Ethnographic Empathy and the Social Context of Rights: “Rescuing” Maasai Girls from Early Marriage.” American Anthropologist 113 (4):632–643. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2011.01375.x

- Boyden, J., A. Pankhurst, and Y. Tafere. 2013. Harmful Traditional Practices and Child Protection: Contested Understandings and Practices of Female Child Marriage and Circumcision in Ethiopia. Oxford: Young Lives, Oxford Department of International Development.

- CARE. 2017. Applying Theory to Practice: CARE’s Journey Piloting Social Norms Measures for Gender Programming. Atlanta: Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere Inc. (CARE)

- Cialdini, R. B., L. J. Demaine, B. J. Sagarin, D. W. Barrett, K. Rhoads, and P. L. Winter. 2006. “Managing Social Norms for Persuasive Impact.” Social Influence 1 (1):3–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15534510500181459

- Cislaghi, B., and L. Heise. 2017. “Measuring Gender-Related Social Norms”. Learning Report 1. London: Learning Group on Social Norms and Gender-Related Harmful Practices of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Cislaghi, B., and L. Heise. 2019. “Using Social Norms Theory for Health Promotion in Low-Income Countries.” Health Promotion International 34 (3):616–623. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day017

- Cislaghi, B., G. Mackie, P. Nkwi, and H. Shakya. 2019. “Social Norms and Child Marriage in Cameroon: An Application of the Theory of Normative Spectrum.” Global Public Health 14 (10):1416–1479. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2019.1594331

- Cislaghi, B., K. Manji, and L. Heise. 2018. “Social Norms and Gender Related Harmful Practices." Learning Report 2. London: Learning Group on Social Norms and Gender-related Harmful Practices of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Efevbera, Y. 2019. “Why Do Young Girls Marry? A Qualitative Study on Drivers of Girl Child Marriage in Conakry, Guinea.” Poster presented at the Women Deliver Conference, Vancouver, Canada, June 3–6.

- Ellis Simonsen, S. M., J. L. Lyon, S. C. Alder, and M. W. Varner. 2005. “Effect of Grand Multiparity on Intrapartum and Newborn Complications in Young Women.” Obstetrics & Gynecology 106 (3):454–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000175839.46609.8e

- Fitzgibbon, C. 2012. Economics of Resilience Study - Kenya Country Report. London: UK Department for International Development.

- Flintan, F. 2008. Women’s Empowerment in Pastoral Societies. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- Galdas, P. 2017. “Revisiting Bias in Qualitative Research: Reflections on Its Relationship With Funding and Impact.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1):1–2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917748992

- Greene, M. E., and S. Ellen. 2019. Social and Gender Norms and Child Marriage: A Reflection on Issues, Evidence and Areas of Inquiry in the Field. London: ALIGN.

- IRIS. 2015. North-Eastern Kenya: A Prospective Analysis. Paris: Institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégiques.

- Johnson, J. M. 2001. “In-Depth Interviewing.” In Handbook of Interview Research, edited by Jaber F. Gubrium and James A. Holstein, 103–119. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Jones, N., B. Tefera, J. Stephenson, T. Gupta, P. Pereznieto, G. Emire, B. Gebre, and K. Gezhegne. 2014. Early Marriage and Education: The Complex Role of Social Norms in Shaping Ethiopian Adolescent Girls’ Lives. London: Overseas Development Institute.

- Kane, S., M. Kok, M. Rial, A. Matere, M. Dieleman, and J. E. Broerse. 2016. “Social Norms and Family Planning Decisions in South Sudan.” BMC Public Health 16 (1):1183. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3839-6

- Kenny, L., H. Koshin, M. Sulaiman, and B. Cislaghi. 2019. “Adolescent-Led Marriage in Somaliland and Puntland: A Surprising Interaction of Agency and Social Norms.” Journal of Adolescent Research 72:101–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.02.009

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF International. 2008. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Rockville, MD: KNBS and ICF International.

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF International. 2015. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Rockville, MD: KNBS and ICF International.

- Khalif, Z. K. 2010. Pastoral Transformation: Shifta-War, Livelihood, and Gender Perspectives among the Waso Borana in Northern Kenya. Ås, Norway: Department of International Environment and Development, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences.

- Kipuri, N., and A. Ridgewell. 2008. A Double Bind: The Exclusion of Pastoralist Women in the East and Horn of Africa. London: Minority Rights Group International.

- Krätli, S., J. Swift, and A. Powell. 2014. Saharan Livelihoods - Development and Conflict. Washington, DC: Sahara Knowledge Exchange, The World Bank.

- Lind, J. 2018. “Devolution, Shifting Centre-Periphery Relationships and Conflict in Northern Kenya.” Political Geography 63:135–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.06.004

- Mackie, G., F. Moneti, H. Shakya, and E. Denny. 2015. What Are Social Norms? How Are They Measured? New York: UNICEF.

- Manda, S., and R. Meyer. 2005. “Age at First Marriage in Malawi: A Bayesian Multilevel Analysis Using a Discrete Time-to-Event Model.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society) 168 (2):439–455. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-985X.2005.00357.x

- Marcus, R., C. Harper, S. Brodbeck, and E. Page. 2015. Social Norms, Gender Norms and Adolescent Girls: A Brief Guide London: Overseas Development Institute.

- McDougal, L., E. C. Jackson, K. A. McClendon, Y. Belayneh, A. Sinha, and A. Raj. 2018. “Beyond the Statistic: Exploring the Process of Early Marriage Decision-Making Using Qualitative Findings from Ethiopia and India.” BMC Women’s Health 18 (144):1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0631-z

- MoALF. 2017. Climate Risk Profile for Wajir County: Kenya County Climate Risk Profile Series. Nairobi: The Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries.

- MoALF. 2018. Climate Risk Profile for Mandera County: Kenya County Climate Risk Profile Series. Nairobi: The Kenya Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries.

- Mtengeti, K., E. Jackson, J. Masabo, A. William, and G. Mghamba. 2008. Children’s Dignity Forum (CDF) Report on Child Marriage Survey Conducted in Dar Es Salaam, Coastal, Mwanza and Mara Regions. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: Children's Dignity Forum.

- National Council for Law Reporting kenya. 2010. “The Children Act.” http://www.childrenscouncil.go.ke/images/documents/Acts/Children-Act.pdf

- Nour, N. M. 2009. “Child Marriage: A Silent Health and Human Rights Issue.” Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology 2 (1):51–56.

- Nyamongo, I. K. 2000. “Factors Influencing Education and Age at First Marriage in an Arid Region: The Case of the Borana of Marsabit District, Kenya.” African Study Monographs 21 (2):55–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.14989/68194

- Petroni, S., M. Steinhaus, N. S. Fenn, K. Stoebenau, and A. Gregowski. 2017. “New Findings on Child Marriage in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Annals of Global Health 83 (5-6):781–790. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aogh.2017.09.001

- Republic of Kenya. 2017. Wajir County Republic of Kenya First County Integrated Development Plan 2013-2017. Nairobi: County Government of Wajir.

- Rumble, L., A. Peterman, N. Irdiana, M. Triyana, and E. Minnick. 2018. “An Empirical Exploration of Female Child Marriage Determinants in Indonesia.” BMC Public Health 18 (1):407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5313-0

- Schaffnit, S. B., M. Urassa, and D. W. Lawson. 2019. “"Child marriage" in Context: Exploring Local Attitudes towards Early Marriage in Rural Tanzania.” Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters 27 (1):1571105–1571304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09688080.2019.1571304

- Scharrer, T. 2018. “Ambiguous Citizens’: Kenyan Somalis and the Question of Belonging.” Journal of Eastern African Studies 12 (3):494–513. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17531055.2018.1483864

- Shell-Duncan, B., A. Moreau, K. Wander, and S. Smith. 2018. “The Role of Older Women in Contesting Norms Associated with Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Senegambia: A Factorial Focus Group Analysis.” PLoS ONE 13 (7):e0199217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199217

- Stark, L. 2018a. “Early Marriage and Cultural Constructions of Adulthood in Two Slums in Dar Es Salaam.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 20 (8):888–901. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1390162

- Stark, L. 2018b. “Poverty, Consent, and Choice in Early Marriage: Ethnographic Perspectives from Urban Tanzania.” Marriage & Family Review 54 (6):565–581. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2017.1403998

- Steinhaus, M., A. Gregowski, N. S. Fenn, and S. Petroni. 2016. ‘She Cannot Just Sit Around Waiting to Turn Twenty’ Understanding Why Child Marriage Persists in Kenya and Zambia. Washington, DC: International Centre for Research on Women.

- Steinhaus, M., L. Hinson, A. T. Rizzo, and A. Gregowski. 2019. “Measuring Social Norms Related to Child Marriage Among Adult Decision-Makers of Young Girls in Phalombe and Thyolo, Malawi.” The Journal of Adolescent Health 64 (4):S37–S44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.12.019

- UNFPA. 2015. Evaluation of UNFPA Support to Population and Housing Census Data to Inform Decision-Making and Policy Formulation 2005-2014, Kenya. New York: United Nations Population Fund.

- UNFPA. 2019. Beyond the Crossing: Female Genital Mutilation across Borders. New York: UNFPA.

- UNICEF. 2019. “Child Marriage.” https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-marriage/

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations.

- Walker, J.-A. 2012. “Early Marriage in Africa - Trends, Harmful Effects and Interventions.” African Journal of Reproductive Health 16 (2):231–240. doi:https://doi.org/10.1201/b13821-7

- Wodon, Q., C. Male, A. Nayihouba, A. Savadogo, A. Yedan, J. Edmeades, A. Kes, et al. 2017. Economic Impact of Child Marriage : Global Synthesis Report. Washington, DC: The World Bank and International Center for Research on Women.

- Yaya, S., E. K. Odusina, and G. Bishwajit. 2019. “Prevalence of Child Marriage and Its Impact on Fertility Outcomes in 34 Sub-Saharan African Countries.” BMC International Health and Human Rights 19 (1):1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-019-0219-1

- Zakaria Maro, G., P. N. Nguura, J. Y. Umer, A. M. Gitimu, F. S. Haile, D. K. Kawai, L. C. Leshore, et al. 2012. Beliefs and values. Understanding Nomadic Realities. Case Studies on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in Eastern Africa. edited by A. van der Kwaak, G. Baltissen, D. Plummer, K. Ferris, and J. Nduba, 21–55. Amsterdam: The African Medical Research Foundation (AMREF) and the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT).