?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

There is limited evidence about the lives of queer Mongolian youth. This is despite mental health problems being a pressing concern among young Mongolians, and international evidence suggesting queer youth may experience more mental health challenges than their non-queer peers. We explored the experiences of queer youth in their immediate environments and navigation of their identities in Mongolian society. In this study, twelve young queer-identifying people aged 18-25 from Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia participated in photo-elicitation interviews. Visual research methods allowed participants to generate rich (visual, textual, and oral) data about their lived experiences. We analysed data using a thematic approach and identified three main themes, each with three sub-themes. Participants reported that peer bullying and gendered expectations at school, heteronormativity and gender role expectation in family settings, along with strong stereotypes about queerness in broader society, substantially impacted participants’ mental and physical wellbeing. Mongolian queer youth need strong support from their immediate environments, such as school and family. Stigma and misconception around queerness remain persistent among the public but young people are continuously resisting the prejudice expressed towards them. Understanding these challenges is crucial to increasing inclusivity in policies and programmes to enhance the wellbeing of young queer Mongolians.

Keywords:

Introduction

Sexuality and gender diversity are important aspects of social identities, as well as essential influences on an individual's life situation and health (Bränström and van der Star Citation2013; Pöge et al. Citation2020). Social contexts, such as a predominant heteronormative culture and gender binary, influence health outcomes between sexual and gender minority and general populations (Meyer Citation2001; Meyer Citation2014). Historically, queer peopleFootnote1 were not recognised by public health researchers as a population with diverse health concerns beyond mental health disorders, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections (Boehmer Citation2002; Byne Citation2021). HIV was initially believed by many to be a ‘homosexual disease’, due to its early recognition among gay men, and disproportionate impact on gay community (Merson et al. Citation2008). Individual-level behavioural change was a fundamental goal of early HIV prevention strategies (Gupta et al. Citation2008); however, structural-level interventions that address age, gender, socioeconomic status, and policy are needed to sustain progress (Coates, Richter, and Caceres Citation2008).

Subsequently, growing understanding of the psychosocial factors that contribute to health disparities between population groups has changed the public health approach (Whitfield et al. Citation2012). It is well documented in high-income countries that health disparities between queer and non-queer youth are significant, particularly regarding mental health (Miranda-Mendizábal et al. Citation2017). Thus, the importance of including sexual and gender minorities in health policies and the need to address the broader health issues faced by queer people have been stressed in recent years (Mule et al. Citation2009). Despite substantial advances, there have been limited improvements and significant unmet health needs in low and middle-income country settings where sexual and gender diversity is stigmatised, and heavily regulated or criminalised (Byne Citation2021; Scheim et al. Citation2020).

Mongolia is home to 3.2 million people in an area of 1.5 million The country has a comparatively young population: 45% of the population is under 25 years of age (NSOM 2020). Mongolian youth are under-researched in general, though existing evidence shows that mental health is a pressing concern with high rates of suicidal ideation and planning, making suicide one of the leading causes of death among youth (Davaasambuu et al. Citation2019). Youth suicide is closely associated with peer bullying and negative emotions such as fear and isolation (Altangerel, Liou, and Yeh Citation2014; Davaasambuu et al. Citation2017). Moreover, research by The LGBT Centre (Citation2017, 2) shows that queer Mongolian youth are at higher risk of developing mental health disorders, substance and alcohol dependence, and suicidal ideation due to the experience of violence and harassment reinforced by queerphobia. The social context and social and structural discrimination create an environment that is not only psychosocially challenging (Koch, Knutson, and Nyamdorj Citation2020) but also physically dangerous for queer Mongolians (Billé Citation2010; Peitzmeier et al. Citation2017). However, there is very limited research evidence published regarding the experience of queer youth in Mongolia (Koch, Knutson, and Nyamdorj Citation2020; UNDP Citation2014).

Historical shifts in sexual and gender diversity in Mongolia

In Mongolia, a nation landlocked by two of the world’s largest countries, Russia and China, sexual and gender diversity have been heavily controlled and influenced by the Government throughout history in ways similar to its powerful neighbours (Nyamdorj Citation2006; Terbish Citation2013). Prior to socialism (before 1921), same sex relationships were common practice in Mongolia, particularly among members of the clergy (Kimura and Berry Citation1990). This occurred despite same sex practices between lamas (Buddhist monks) being considered wrong from a monastic perspective, as they were viewed as a failure to resist carnal desire (Terbish Citation2013). Likewise, during the pre-socialist era, transgender was widely acknowledged by Mongolians, particularly in shamanistic culture, which was central feature of Mongolian society up until the late 17th century. Gender roles of chosen shamans were often reversed: male shamans were known to marry men and live as women through dress, doing female chores with other women, or vice versa (Devereux Citation1937). Despite this traditional acceptance, there is a limited written history of same sex relationships and practices, and gender diversity, before the 20th century (UNDP 2014), and ‘homosexuality’ was described only as an activity, not a separate identity (Terbish Citation2013).

The socialist regime assumed power for seven decades (1921-1990) in Mongolia (Bruun and Narangoa Citation2011), and non-productive sex or sexuality as desire was officially condemned by the government. Accordingly, all forms of sexual activity with no link to reproduction were referred to as ‘sexual problems’ which were not supposed to exist among residents. Homosexuality was also seen as a mental disorder and a threat to society, and homosexuals were considered enemies of socialist morals and traitors to the nation (Billé Citation2010). As part of the Soviet agenda, homosexuality was outlawed by the Government of Mongolia, defined as an act of perversion, and forbidden by Section 113 of the Criminal Code of Mongolia (Nyamdorj Citation2006). Homosexuality was defined as an act only between men, not between women; sex between women was not mentioned by the law which made it officially non-existent (Terbish Citation2013). The section prohibiting male homosexual acts was changed after similar sections had been repealed from laws of the Union of Soviet Socialist RepublicsFootnote2, early in the Perestroika and Glasnost movements (Kurvinen Citation2007).

A peaceful transition to democracy took place in Mongolia in the 1990s, with human rights and political freedoms enshrined in the new Constitution of 1992 and other legislation. However sexual orientation and gender identity remained unarticulated in most legislation (Nyamdorj Citation2006). Post-socialist, democratic Mongolia has provided an opportunity for civil rights issues to expand (UNDP 2014) but views on sexuality have not shifted substantially (Terbish Citation2013). It is also notable that the Soviet agenda has contributed to the development of strong and persistent nationalist ideology created out of fear and hatred towards, China (Billé Citation2014). Mongolian nationalism attaches great importance to the reproductive power of women to ensure national security, as well as to maintain the purity of Mongol blood (Billé Citation2015). Controlling female sexuality has therefore been a key part of nationalist rhetoric, limiting sexual relationships between Mongolian women and foreign men (Billé Citation2015). Further, Mongolia remains a patriarchal environment as a nomadic country with a proud military history. Men in Mongolia are highly valued for their masculinity, particularly their bodily strength and physical stamina (Billé Citation2010). Accordingly, it is not only a sexist and gendered practice but also heteronormative ideology that has caused ‘homosexuals’ to be viewed as national threats unable (or unwilling) to contribute to national reproduction (Billé Citation2010).

Today, consensual same sex practices between adults are legal in Mongolia, and sexual orientation and gender identity are protected characteristics in the Criminal Code (Government of Mongolia Citation2017). Yet, significant levels of stigma and discrimination persist at social and systemic levels, and the queer community remains substantially marginalised (The LGBT Centre Citation2019). For example, in a recent study most men who have sex with men reported clinical depression, and 73% of Mongolian queer people had considered suicide because of social intolerance and lack of acceptance (UNDP 2014). Furthermore, access to mental health care remains poor, with community members experiencing double discrimination due to their queer status (Koch, Knutson, and Nyamdorj Citation2020).

To our knowledge, no research in Mongolia has documented the experiences of queer youth as they navigate their identities and social environments. We aim to fill this gap by using visual research methods to explore and understand how young queer Mongolians view their identities and navigate their lives in a society that is experiencing both rapid social awareness and persistent queer discrimination.

Materials and methods

In this project, participant-generated photographs were used as the basis for photo-elicitation interviews with queer Mongolian youth. Photo-elicitation enables participants to communicate their perceptions, emotions, and experiences visually as well as orally, and encourages participatory and collaborative knowledge creation processes (Rose Citation2014). Visual methods are well recognised for their potential to engage populations who have been marginalised from research, enabling them to generate meanings on their own terms (Warr et al. Citation2016).

Participants, sampling and recruitment

Young people aged 18-23 who identified as queer (or any LGBTQ+ identity), and were currently living in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia were eligible for participation. Participants were purposively sampled based on these inclusion criteria. In studies such as this, informational power suggests that sample sufficiency, the quality of collected data, and variability of pertinent occurrences are more crucial than the number of participants. Therefore, a smaller number of participants may be adequate if the sample holds information that is relevant for the study (Malterud, Siersma, and Guassora Citation2016).

In this study, our sample is small (comprising 12 individuals in total) but provides rich information from people with diverse backgrounds. The sample includes participants with a broadly shared LGBTQ+ identity and some similarities in life history, such as growing up in the same period in Mongolia but represents sub-communities with considerable diversity of life experiences. Subsequently, the chosen methods allowed diverse participants to provide rich data through multiple techniques.

Social media, particularly Facebook, was used as the main recruitment tool with the help of a local community organisation, The LGBT Centre in Ulaanbaatar. The study recruitment flyer was posted on DG’s Facebook profile and other queer-specific groups on Facebook. The LGBT Centre also distributed research flyers via their Facebook and Instagram pages directing potential participants to the lead researcher (DG).

Data collection

Once potential participants had expressed interest in the project, they were contacted individually by DG for a one-to-one meeting (Zoom or Facebook depending on individual’s preference) with an explanation about the research project and tasks. DG is a Mongolian LGBTQ+ activist who has worked at the LGBT Centre in Ulaanbaatar. His gay identity and known history of activism helped him establish trust and rapport with participants.

Each participant was asked to complete three tasks: (1) attend an introductory meeting to discuss the research project and to provide informed consent, (2) take photographs and generate up to three photostories (photograph accompanied with short description of its significance), and (3) participate in a photo-elicitation interview. The process of the photostory activity, the ethical issues associated with photo-taking, and the appropriate use of photographs in the research project were explained to participants. These introductory meetings allowed participants to ask questions and explained to them about the privacy and confidentiality including the risk of identity exposure and how to avoid such risks. Participants were given the DG’s contact details and were encouraged to approach him for any further clarification. During the introductory meetings, each participant was provided with a plain language statement describing the study and advised to read it before signing a consent form.

Next, participants were asked to use their own devices (e.g. mobile phone) to generate up to three photographs with brief descriptions based on their everyday experience as queer youth living in Ulaanbaatar. Photostory data were collected at participants’ homes or in their local communities (as allowed under COVID-19 related restrictions in force when the photographs were taken). Finally, participants were asked to provide their photographs along with descriptions to be used as stimuli during a one-on-one interview. This method is called a photo-elicitation ‘autodriven’ interview (Clark Citation1999). Interviews took place in an open-ended style supported by a previously developed interview guide (see supplemental online Appendix 1). This style allowed the interviewer to initiate and guide the discussion using participant photographs as a prompt, while to allowing space for the interviewee to describe personal experiences (Lapenta Citation2011).

All interviews were conducted in Mongolian, audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English by DG. Relevant data generated include photographs (36 photographs), short descriptions or stories alongside each photograph (36 stories), and transcripts of 12 photo-elicitation interviews (13 h).

Data analysis

Photo descriptions and transcripts from the photo-elicitation interviews were reviewed to identify recurring concepts and experiences. This initial review process enabled us to categorise the data through preliminary coding. Transcripts were analysed thematically using an inductive approach (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Through initial and axial coding, connections were identified between the different categories and three main themes, each with three sub-themes, were developed across repeated patterns of meaning. Thematic analysis enabled us to assess the ways in which specific aspects of participants’ lives were seen as shaping their identities to navigate life in Mongolia (Liamputtong Citation2012). Common Mongolian names were used as pseudonyms in this paper to maintain participants’ confidentiality.

Findings

Fifteen young people were interested in the project and met the inclusion criteria, with data from 12 of them included in this analysis (three withdrew due to unavailability for interview due to COVID-19 restrictions). presents the sociodemographic characteristics of each participant. Of the 12 participants, seven self-identified as male including one trans male, five self-identified as female including one trans female. Eight participants identified as cisgender and four identified along the transgender spectrum. Six identified as gay, one as lesbian, two as heterosexual, two as bisexual and one as queer.

Table 1. Participants' age, sexual orientation and gender identity.

Three main themes, each with three sub-themes, were developed based on the young queer people’s experience from the analysis: (1) experience at high school; (2) experience in the family; (3) experience in broader society.

Experience at high school

Experience navigating queer identities in an unsupportive environment during high school were commonly reflected on by participants who identified (1) peer bullying; (2) gendered expectations at school; and (3) lack of support from teachers as sub-themes within this theme. Participants described how these high school experiences caused mental and emotional stress had long-term effects for some participants.

Peer bullying

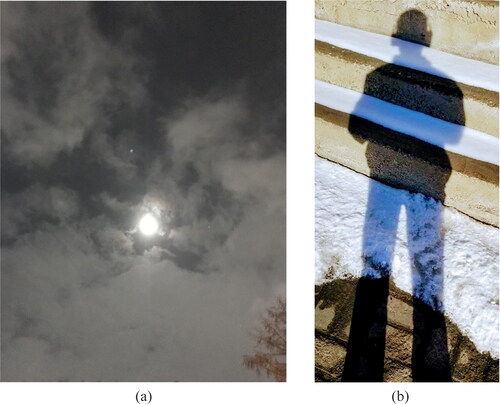

Participants had experienced different forms of peer bullying, including verbal abuse and physical violence (). Male participants reported experiencing more serious forms of verbal abuse and physical violence from their peers, compared with female participants. Participants reported that name-calling, emotional and physical abuse often led to serious psychological consequences, including feelings of fear and loneliness, loss of self-worth, denial of queer identity, and suicidal thoughts.

Figure 1. (a): It was only the moon that I used to express my true self, the fear I was afraid to tell anyone or write on any paper. (b): From an early age, I was often bullied and teased by classmates. I began to live in constant fear that if my classmates, family and loved ones somehow found out.

Physical violence was reported by gay male participants. It was a traumatic experience for several of them to recall:

More than 10 of my male classmates forcibly stripped me naked in the classroom. They joked about whether I was male or female and wanted to check if I have a penis. It is hard to think even now. I kept it a secret and never told anyone else. – Bayar, 21, gay man.

Participants reported that constant bullying put queer youth under a lot of stress, and led some of them to consider and even attempt suicide:

I felt worthless being feminine, and not being like the other boys… After a while, I started asking myself, ‘Why am I alive, what am I living for?’ so it felt more difficult, and it led me to attempt suicide. - Bold, 21, gay man.

Gendered expectations

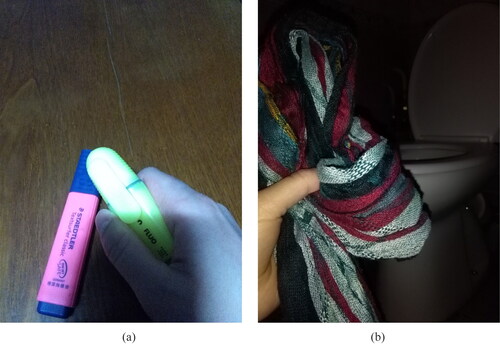

Gendered expectations were seen as strong influences on school-based bullying (). Experiences of peer bullying were perceived differently by young queer boys and girls, and the type and level of bullying differed among the latter based on their gender expression. Boys’ experiences suggest that they are bullied primarily based on effeminate traits and were targeted due to perceptions that they were not masculine enough, while masculine traits helped some boys to avoid peer bullying.

Figure 2. Photo stories depicting experiences with gendered culture. Descriptive captions are in the participants’ own words. (a): I needed a highlighter for homework, but there was only a pink one in the house. I am very afraid of using pink because if I use pink, I feel like a woman. So, I bought the yellow. (b): I stole my grandma’s scarf to bind my chest in the bathroom. Many of my memories were spent in the bathroom. Because I created my true self there.

I didn’t have that many problems other than questioning my sexuality, but what is happening to my feminine male friend seems very dangerous to me. I was afraid of him being beaten up or losing his confidence because people are making fun of his effeminacy. - Tuya, 21, queer non-binary.

Participants also reported how gender expectations led them to tolerate bullying and blame their own gender expression as being the cause of violence. Seeking support was seen as a weak and feminine thing to do, so shame and guilt prevented some young men from reaching out for support:

Even though I was gay, I always thought of myself as a man. Therefore, I thought it was such a girly thing to tell someone like my parents or teacher about what was happening. – Delger, 20, gay man.

Participants described how Mongolian schools required students to follow a strongly gendered code of dressing, including hairstyle. Gender culture in school impacted particularly on trans and gender diverse youth, with trans boys being forced to wear skirts and keep their hair long to fit dominant expectations. Gender discomfort meant some trans young people found being around their peers challenging:

I used to like playing basketball. In the beginning, I played basketball with girls but eventually the feeling of being a man increased and [I] started being uncomfortable among the girls’ team, so I distanced myself from the sport. – Turuu, 20, transman.

Lack of support

Participants stressed lack of positive and reliable information on queer issues within the school curriculum and the lack of support from teachers and school administrators regarding bullying. Same sex relationships and gender diversity were briefly mentioned (usually in health education classes), with information being delivered negatively and in line with teachers’ own prejudices.

LGBT issues were discussed according to a textbook. However, the teacher explained that women become lesbians when they start getting pleasure without the presence of men. I remember being scared of becoming a lesbian at that time. – Naraa, 22, genderqueer lesbian.

Participants reported being frustrated by the homophobic attitudes of teachers, and afraid to seek support from teachers due to a lack of trust in them. Many had to go through bullying on their own without proper support. Studying hard and being a good student was perceived as strategies to diminish the experience of peer bullying and helped some queer youth make friends with their classmates.

Experience in the family

Participants observed their families’ attitudes towards LGBT issues, whether positive or negative, over a long time period, feeling that experiences within the family had strongly influenced their overall outlook on life. Within the main theme of family experience, three sub-themes were identified: fear of homelessness; pressure of heteronormativity, and coming out to parents.

Fear of homelessness

Fear of homelessness was commonly expressed in association with identity exposure. Some young people were certain that they would be abandoned by their parents if their identities were exposed. Negative attitudes towards queer people were regularly seen by queer youth in the family home. Moreover, witnessing friends become homeless due to identity exposure contributed to the fear that the same thing would happen to them. The fear of homelessness often involved domestic violence as well.

Dad once came home drunk and beat me. Then he kicked me out for being gay. I came back home the next morning. What happened that night made me realise that if I choose this life, my family will push me away from their life eventually – Bat, 21, gay man.

Pressure of heteronormativity

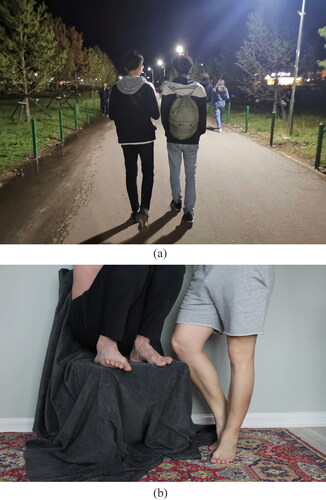

Young people reported that they were put under a lot of pressure by their family and relatives to fit into a heteronormative ideal (). Participants also described how the male child in the family was considered the one who passes the family line down to the next generation, while the female child was considered as someone who will belong to another family after marriage. Not meeting parents’ heteronormative expectations created self-conflict among participants and led them to experience shame and guilt for being queer. Furthermore, heteronormative expectations were seen not only as a source of pressure for queer youth but also for parents having to answer relatives asking, ‘why is your child still single and not getting married or giving birth?’.

Figure 3. (a): Pretending to be just friends with my boyfriend since we cannot show our love like holding hands in public without fear. (b): My boyfriend and I decided to move in together since there was no place for us. This is the only home for us to be who we are, loving and caring for each other as we wish.

Coming out to family

Half of the participants had come out to their parents as queer or had their identity exposed in some way. In most cases, they chose to come out first to their mothers, and their reactions were seen as at least partially positive though none of them actively supported their child to be who they were:

I told my mother that I was seeing a girl… She was not angry and then I received a message, ‘I didn’t like what you said yesterday but I love you’. Then I knew that my mother didn’t want to talk about it again – Saraa, 21, bisexual, woman.

Parents commonly thought queerness was a phase to be passed through and that their children could eventually choose heterosexual lives. Parents of girls, in particular, believed that giving birth would change them and lead them to a heterosexual way of life. Furthermore, parents perceived homosexuality to be an acquired or learned behaviour, and that therefore unlearning this behaviour through psychological treatment seemed logical:

My parents found out that I am gay by checking my phone. Mom wanted to see a psychiatrist and get me treated… I promised her that I will suppress this desire of mine – Delger, 20, gay man.

Experience of broader society

Participants’ experience of broader society included homophobia and transphobia driven by misconceptions and stereotypes around sexual and gender diversity. However, queer visibility among the younger generation had increased significantly as a result of improved access to information. Three sub-themes were identified: common misconceptions, responsibilities, and progress.

Common misconceptions

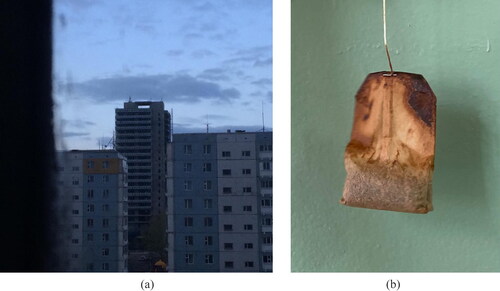

Strong misconceptions around sexual and gender diversity in Mongolian society, such as the idea that homosexuality is acquired, significantly contributed to stigma and discrimination (). It was a common experience among participants to be asked if they were born gay or had become so.

Figure 4. (a): Today I posted a picture that I took when no one noticed my homosexuality but instead they shared their love for a gloomy day. That's it, it has nothing to do with me being a homosexual. (b): The wall represents the LGBT people, and the bag of tea is portraying the mindset of this society. The mindset of this society is like this tea packed in a bag.

My aunt asked me if there was any external influence on my homosexuality. If there is no external influence, you are born gay, she said – Zorig, 20, gay man.

Another misconception was the conflation of homosexuality with paedophilia, which caused fear and strong homophobia. Both of these misconceptions were used by people to justify their homophobic and transphobic actions, and prevent queer issues being discussed in public. Furthermore, trans women are often portrayed in the media as sex workers while trans men remain invisible.

Responsibilities

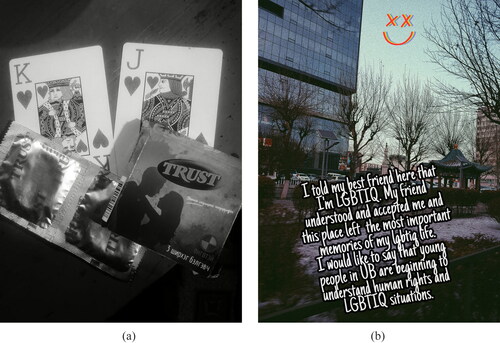

Participants reported it was easy for the public to judge the entire queer community on a single event or on one queer person’s bad behaviour (). Young peopled reported feeling enormous pressure to change negative public narratives about queer people, as they felt they lived in a society where the media and entertainment industries misled public opinion about queer issues:

Figure 5. (a): I noticed people become intimate with each other, not for love but for sexual gratification. That suggests that these people are more likely to be sexually exploited and exposed to STIs. (b): I came out to my friend here. My friend understood and accepted me. I’d say young people in UB are beginning to understand human rights and LGBTIQ situations.

Living in a society that does not fully recognise LGBT people, we feel like living with a burden to be responsible. Based on one person’s behaviour, people come up [to us] and say things like ‘Fags and Lesbos are overstepping the boundaries.’ – Saraa, 21, bisexual woman.

Moreover, a feeling of responsibility led some queer youth to be critical of their community members. They criticised other queer youth for being hypersexual and irresponsible, and for contributing to the existing stereotypes instead of fighting against them.

Progress

All participants described how Mongolian society was beginning to change (). Improved access to information through the digital media helped people to become more positive and participants described their lives as easier compared to those of the older queer generation in Mongolia. Social media and western queer culture were seen as having a significant influence over participants’ personal growth and self-acceptance:

Watching a foreign gay couple’s blog on YouTube made me feel very close to them. Then I started thinking that living as a gay person is not wrong. At first, I hated myself, but then I became proud of it – Amar, 20, gay male.

The social media allowed young queer people to be more visible and open, to access accurate information in their native language, and know more about the local queer movement. Looking at other young queer people being out and proud empowered participants to feel good about themselves and accept who they are.

Recently, a Mongolian lesbian couple started their blog videos. It was like a bomb. This is the perfect example of openly LGBT people that encourages others to live out and be proud. I hope that accepting and loving myself may inspire someone else and help them to understand themselves a little more – Tuya, 21, queer non-binary.

Discussion

In this study, we sought to understand how queer youth navigate their identities and social environments in Ulaanbaatar. Participants reported their high school years were highly stressful, and they had to live under constant fear of emotional and physical abuse due to peer bullying. The impact of peer bullying, homophobia and transphobia on stress and mental health is well established in the literature (Ahuja et al. Citation2015; Garaigordobil and Larrain Citation2020; Meyer Citation2003; Ream Citation2019; Rosenstreich Citation2013; Stone et al. Citation2014). Teachers’ attitudes at high school were perceived as prejudicial against queer students and promoted peer bullying instead of preventing it, providing a missed opportunity for community and social support.

Participants expressed how conservative gender norms and heteronormativity remained unchanged and strongly valued in Mongolia, with negative impacts on queer youth. Hypermasculinity and bodily strength in men is highly valued in Mongolian culture (Billé Citation2015), with many young queer men being bullied for being not masculine enough. Social pressure from parents and relatives to enter into heteronormative relationships contributed to young people’s fear of identity exposure and shaped the decision to keep their identity hidden.

Internationally, youth who identify as queer are overrepresented among those who experience homelessness (Forge et al. Citation2018), and queer-identified youth are more likely to experience family rejection and domestic violence compared with their non-queer peers (Liu and Mustanski Citation2012; Wilson and Kastanis Citation2015). In this study, some participants reported that their parents knew they were queer. While mothers were seen as accepting but not supportive of their child’s queer identity, fathers were described as more likely to be violent when their of their children’s queer identity. This poses a fundamental risk to queer youth navigating such identities in their home and family environments.

The local queer movement in Mongolia was appreciated by some participants, who noted that the movement actively promotes queer visibility, which can be utilised to promote the health and well-being of young queer Mongolians. Community organisations fostered a sense of belonging that made participants feel they were not alone and helped them to generate positive emotions of acceptance, pride, and hope. These positive emotions played a significant role in supporting mental well-being, being reliable indicators of a person's physical, psychological and social well-being (Fredrickson et al. Citation2008). Simultaneously, participants felt responsible for representing the queer community positively to change negative stereotypes and narratives and create a more welcoming and accepting social environment.

Limitations and strengths

It is important to recognise that participants in this study did not include young people who lived outside of Ulaanbaatar; were under 18 or over 25 years of age; and/or were members of a sexual and gender minority but did not identify as queer. In addition, the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic and some participants were interviewed during lockdown when partners or family members were home, which may have limited what they felt safe or able to discuss. Indeed, two eligible participants dropped out because of these challenges.

In terms of its strengths, the study is among the first to focus on the lived experiences of young queer people in Mongolia and use multiple data sources (photographs, photostories and interviews) to provide insights into their lives. Findings provide data on queer youth experience, which can be used by community organisations seeking to engage with members of this group. In addition, the findings may help stimulate future research and policies more inclusive of a group that has been historically marginalised. Finally, the analysis may contribute to decreasing negative attitudes and encouraging health professionals to provide more culturally sensitive, non-discriminatory services, particularly in the area of mental health.

Conclusion

This paper offers unique insights into young queer Mongolians' lived experience. Findings suggest that emotional and physical abuse are common for queer youth in school and in the family. Peer bullying was a pressing concern in the school setting, while homelessness associated with domestic violence was both experienced and feared by participants in the family setting. Heteronormativity and gender expectations alongside harmful misconceptions about queerness remain strong in Mongolian families and broader society, which reinforced the negative experiences that young people in this study faced daily. These experiences had significant impacts on mental, physical and social well-being and resulted in concerning emotions and behaviours such as fear and loneliness, identity denial, loss of self-worth and suicide attempts. However, participants narratives highlighted how growing queer visibility and progress towards queer rights in Mongolia, provide opportunities to strengthen support to LGBTQ+ Mongolians in the future.

tchs_a_1998631_sm0550.docx

Download MS Word (37.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to all queer-identified young Mongolians who participated in this study and who shared their experiences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are not publicly available due to concerns about maintaining the privacy of the research participants but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Throughout this paper, we use the term ‘queer’ interchangeably with LGBTQ+ to refer to people whose gender and/or sexuality are excluded from cultural norms (Shlasko Citation2005) because young people themselves show strong support for its use (Zosky and Alberts Citation2016). In addition, the local LGBT Centre uses the term queer to refer to members of this community, particularly in youth settings and programmes, despite the fact that the term ‘queer’ not yet widely embraced by the mainstream media and older LGBTQ+ people in Mongolia.

2 Mongolia was not part of USSR, but was a satellite state of the Soviet Union, and therefore the Criminal Code of Mongolia was substantially influenced by the laws of USSR at that time.

References

- Ahuja, A., C. Webster, N. Gibson, A. Brewer, S. Toledo, and S. Russell. 2015. “Bullying and Suicide: The Mental Health Crisis of LGBTQ Youth and How You Can Help.” Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health 19 (2): 125–144. doi:10.1080/19359705.2015.1007417

- Altangerel, U., J.-C. Liou, and P.-M. Yeh. 2014. “Prevalence and Predictors of Suicidal Behavior Among Mongolian High School Students.” Community Mental Health Journal 50 (3): 362–372. doi:10.1007/s10597-013-9657-8

- Billé, F. 2010. “Different Shades of Blue: Gay Men and Nationalist Discourse in Mongolia.” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 10 (2): 187–203.doi:10.1111/j.1754-9469.2010.01077.x.

- Billé, F. 2014. Sinophobia: Anxiety, Violence, and the Making of Mongolian Identity. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Billé, F. 2015. “Nationalism, Sexuality and Dissidence in Mongolia.” In Routledge Handbook of Sexuality Studies in East Asia, edited by Mark McLelland and Vera Mackie, 162–173. London: Routledge.

- Boehmer, U. 2002. “Twenty Years of Public Health Research: Inclusion of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Populations.” American Journal of Public Health 92 (7): 1125–1130. doi:10.2105/AJPH.92.7.1125.

- Bränström, R., and A. van der Star. 2013. “All Inclusive Public Health-what about LGBT populations?” The European Journal of Public Health 23 (3): 353–354. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckt054

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bruun, O., and L. Narangoa. 2011. Mongols from Country to City: Floating Boundaries, Pastoralism and City Life in the Mongol Lands. Copenhagen: Nias Press.

- Byne, W. 2021. “LGBTQ Health Research: Theory, Methods, and Practice.” LGBT Health 8 (1): 88–89. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2020.0388

- Clark, C. D. 1999. “The Autodriven Interview: A Photographic Viewfinder into Children’s Experience.” Visual Sociology 14 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1080/14725869908583801

- Coates, T. J., L. Richter, and C. Caceres. 2008. “Behavioural Strategies to Reduce HIV Transmission: How to Make Them Work Better.” The Lancet 372 (9639): 669–684.

- Davaasambuu, S., S. Batbaatar, S. Witte, P. Hamid, M. A. Oquendo, M. Kleinman, M. Olivares, and M. Gould. 2017. “Suicidal Plans and Attempts Among Adolescents in Mongolia: Urban Versus Rural Differences.” Crisis 38 (5): 330–343. doi:10.1027/0227-5910/a000447.

- Davaasambuu, S., H. Phillip, A. Ravindran, and P. Szatmari. 2019. “A Scoping Review of Evidence-Based Interventions for Adolescents with Depression and Suicide Related Behaviors in Low and Middle Income Countries.” Community Mental Health Journal 55 (6): 954–972. doi:10.1007/s10597-019-00420-w.

- Devereux, G. 1937. “Institutionalized Homosexuality of the Mohave Indians.” Human Biology 9 (4): 498–527.

- Forge, N., R. Hartinger-Saunders, E. Wright, and E. Ruel. 2018. “Out of the System and onto the Streets: LGBTQ-Identified Youth Experiencing Homelessness with Past Child Welfare System Involvement.” Child Welfare 96 (2): 47–74.

- Fredrickson, B. L., M. A. Cohn, K. A. Coffey, J. Pek, and S. M. Finkel. 2008. “Open Hearts Build Lives: Positive Emotions, Induced Through Loving-Kindness Meditation, Build Consequential Personal Resources.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95 (5): 1045–1062. doi:10.1037/a0013262.

- Garaigordobil, M., and E. Larrain. 2020. “Bullying and Cyberbullying in LGBT Adolescents: Prevalence and Effects on Mental Health.” Comunicar 28 (62): 79–90. doi:10.3916/C62-2020-07.

- Government of Mongolia. 2017. Criminal Law. https://www.legalinfo.mn/law/details/11634

- Gupta, G. R., J. O. Parkhurst, J. A. Ogden, P. Aggleton, and A. Mahal. 2008. “Structural Approaches to HIV Prevention.” The Lancet 372 (9640): 764–775. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9

- Kimura, H., and S. Berry. 1990. Japanese Agent in Tibet: My Ten Years of Travel in Disguise. London: Serindia Publications, Inc.

- Koch, J. M., D. Knutson, and A. Nyamdorj. 2020. “LGBT Mental Health in Mongolia: A Brief History, Current Issues, and Future Directions.” In LGBTQ Mental Health: International Perspectives and Experiences, edited by Nadine Nakamura, and Carmen H. Logie, 89–102. Washington: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/0000159-007

- Kurvinen, H. 2007. “Homosexual Representations in Estonian Printed Media During the Late 1980s and Early 1990s.” In Beyond the Pink Curtain: Everyday Life of LGBT People in Eastern Europe, edited by Jidt Takács, and Roman Kuhur, 287–301. Ljubljana: Mirovni Inšt.

- Lapenta, F. 2011. “Some Theoretical and Methodological Views on Photo-Elicitation.” In The SAGE Handbook of Visual Research Methods, edited by Eric Margolis and Luc Pauwels, 201–213. London: SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781446268278.n11

- Liamputtong. 2012. Qualitative Research Methods. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/unimelb/detail.action?docID=4882799.

- Liu, R. T., and B. Mustanski. 2012. “Suicidal Ideation and Self-Harm in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 42 (3): 221–228. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.10.023.

- Malterud, K., V. D. Siersma, and A. D. Guassora. 2016. “Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power.” Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1753–1760. doi:10.1177/1049732315617444

- Merson, M. H., J. O'Malley, D. Serwadda, and C. Apisuk. 2008. “The History and Challenge of HIV Prevention.” The Lancet 372 (9637): 475–488. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60884-3

- Meyer, H. H. 2001. “Why Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Public Health?” American Journal of Public Health 91 (6): 856–859. doi:10.2105/ajph.91.6.856

- Meyer, I. H. 2003. “Prejudice, Social Stress, and Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Populations: Conceptual Issues and Research Evidence.” Psychological Bulletin 129 (5): 674–697. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

- Meyer, I. H. 2014. “Minority Stress and Positive Psychology: Convergences and Divergences to Understanding LGBT Health.” Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 1 (4): 348–349. doi:10.1037/sgd0000070.

- Miranda-Mendizábal, A., P. Castellví, O. Parés-Badell, J. Almenara, I. Alonso, M. J. Blasco, A. Cebrià, A. Gabilondo, M. Gili, C. Lagares, et al. 2017. “Sexual Orientation and Suicidal Behaviour in Adolescents and Young Adults: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” The British Journal of Psychiatry 211 (2): 77–87. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.116.196345

- Mule, N. J., L. E. Ross, B. Deeprose, B. E. Jackson, A. Daley, A. Travers, and D. Moore. 2009. “Promoting LGBT Health and Wellbeing through Inclusive Policy Development.” International Journal for Equity in Health 8 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-8-18.

- National Statistics Office of Mongolia. 2020. Mongolian Statistical Information Services: Population. https://www.1212.mn/stat.aspx?LIST_ID=976_L03

- Nyamdorj, A. 2006. Life Denied: LGBT Human Rights in the Context of Mongolia’s Democratisation & Development. http://www.afdenver.net/documents/LGBTHRinMNG_Anaraa.pdf

- Peitzmeier, S. M., R. Stephenson, A. Delegchoimbol, M. Dorjgotov, and S. Baral. 2017. “Perceptions of Sexual Violence among Men Who Have Sex with Men and Individuals on the Trans-Feminine Spectrum in Mongolia.” Global Public Health 12 (8): 954–969. doi:10.1080/17441692.2015.1114133.

- Pöge, K., G. Dennert, U. Koppe, A. Güldenring, E. B. Matthigack, and A. Rommel. 2020. “The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex People.” Journal of Health Monitoring 5 (1): 1–27.

- Ream, G. L. 2019. “What's Unique About Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth and Young Adult Suicides? Findings From the National Violent Death Reporting System.” The Journal of Adolescent Health 64 (5): 602–607. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.10.303.

- Rose, G. 2014. “On the Relation between “visual Research Methods” and Contemporary Visual Culture.” The Sociological Review 62 (1): 24–46. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.12109.

- Rosenstreich, G. 2013. LGBTI People: Mental Health and Suicide. Sydney: National LGBTI Health Alliance.

- Scheim, A., V. Kacholia, C. Logie, V. Chakrapani, K. Ranade, and S. Gupta. 2020. “Health of Transgender Men in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review.” BMJ Global Health 5 (11): e003471–13. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003471.

- Shlasko, G. D. 2005. “Queer (v.) Pedagogy.” Equity & Excellence in Education 38 (2): 123–134. doi:10.1080/10665680590935098.

- Stone, D. M., F. Luo, L. Ouyang, C. Lippy, M. F. Hertz, and A. E. Crosby. 2014. “Sexual Orientation and Suicide Ideation, Plans, Attempts, and Medically Serious Attempts: Evidence From Local Youth Risk Behavior Surveys, 2001-2009.” American Journal of Public Health 104 (2): 262–271. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301383.

- Terbish, B. 2013. “Mongolian Sexuality: A Short History of the Flirtation of Power with Sex.” Inner Asia 15 (2): 243–271. doi:10.1163/22105018-90000069. .

- The LGBT Centre. 2017. LGBTI Children and Adolescents in Mongolia: An Overview of the Situation-2017 Report. http://lgbtcentre.mn/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/LGBTI-children-and-adolescents-in-Mongolia.pdf

- The LGBT Centre. 2019. Submission to the Human Rights Council at the Human Rights Council at the 36th Session of the Universal Periodic Review: Mongolia. http://lgbtcentre.mn/2019/10/29/submission-of-the-lgbt-centre-mongolia-for-the-36th-session/

- UNDP. 2014. Being LGBT in Asia: Mongolia Country Report. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/rbap/docs/Research%20&%20Publications/hiv_aids/rbap-hhd-2014-blia-mongolia-country-report.pdf

- Warr, D., J. Waycott, M. Guillemin, and S. Cox. 2016. “Ethical Issues in Visual Research and the Value of Stories from the Field.” In Ethics and Visual Research Methods: Theory, Methodology, and Practice, edited by Deborah Warr, Marilys Guillemin, Susan Cox, and Jenny Waycott, 1–16. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-54305-9_1

- Whitfield, K. E., L. M. Bogart, T. A. Revenson, and C. R. France. 2012. “Introduction to Special Section on Health Disparities.” Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine 43 (1): 1–3.

- Wilson, B. D. M., and A. A. Kastanis. 2015. “Sexual and Gender Minority Disproportionality and Disparities in Child Welfare: A Population-Based Study.” Children and Youth Services Review 58 (November): 11–17.

- Zosky, D. L., and R. Alberts. 2016. “What’s in a Name? Exploring Use of the Word Queer as a Term of Identification within the College-Aged LGBT Community.” Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 26 (7–8): 597–607.