Abstract

This study explored the intersecting forms of stigma experienced by HIV-serodifferent couples with unmet reproductive goals in rural Uganda. The parent mixed-methods study, which included 131 HIV-exposed women with plans for pregnancy, offered comprehensive HIV prevention counselling and care over a nine-month period. In-depth interviews were conducted with 37 women and seven male partners to explore care experiences and the use of safer conception strategies. This secondary analysis explored how challenges conceiving informed pregnancy plans and HIV prevention behaviours. The following themes were developed (1) partnership conflicts arise from HIV- and infertility-related forms of stigma, contributing to gender-based violence, partnership dissolution and the pursuit of new partners; (2) cultural and gender norms pressure men and women to conceive and maintain partnerships, which is complicated by the stigma directed towards serodifferent couples; (3) frustration with low partner participation in safer conception strategies led to the decreased use of these methods of HIV prevention; (4) health care provider support promotes continued hope of conception and helps overcome stigma. In HIV-affected partnerships, these intersecting forms of stigma may impact HIV prevention. Seeking to fulfil their reproductive needs, partners may increase HIV transmission opportunities as they engage in condomless sex with additional partners and decrease adherence to prevention strategies. Future research programmes should consider the integration of fertility counselling with reproductive and sexual health care.

Introduction

Experiences with infertility and difficulties conceiving affect many couples and individuals around the world (Mascarenhas et al. Citation2012). In Uganda, the fertility rate is high at 4.8 births per woman (The World Bank Citation2019), and gender norms and community and familial expectations pressure married couples to bear children (Dierickx et al. Citation2018; Beyeza-Kashesy et al. Citation2010; Heys et al. Citation2012; Mindry et al. Citation2017). Infertility care is mostly limited to the private sector in Uganda, and infertility stigma limits care-seeking (Kudesia et al. Citation2018). Enacted stigma exhibited as social exclusion, verbal and physical abuse, and internalised stigma exhibited as depression and anxiety, can lead to emotional, partnership and social strain for men and women (Dierickx et al. Citation2018; Anokye et al. Citation2017). Partnership strain may lead to violence against women, which is experienced by 50% of Ugandan women aged 15–49 during their lifetime (UBOS and ICF 2018). Men and women experiencing infertility and associated stigma may pursue new or additional partners and withdraw spousal economic support (Anokye et al. Citation2017; Dhont et al. Citation2011). Among couples affected by HIV, these behaviours may increase the risk of HIV transmission (Lubega et al. Citation2015; Twa-Twa, Nakanaabi, and Sekimpi Citation1997).

The prevalence of HIV is 5.4% among people of childbearing age in Uganda (UNAIDS Citation2020). People living with HIV and their partners can face HIV-related stigma and discrimination, especially regarding reproductive goals. Many HIV-affected couples and individuals fear negative reactions from healthcare providers and community members regarding having condomless sex in an effort to conceive (Davey et al. Citation2018). Individuals who insist on regular condom use with long-term partners may experience higher levels of HIV-related stigma and distrust within their partnerships (Williamson et al. Citation2006), but the risk of HIV acquisition and transmission of other STIs is higher among those who engage in condomless sex to conceive (Grosskurth et al. Citation2000; Grosskurth et al. Citation1995; Brubaker et al. Citation2011). Despite persistent stigma surrounding childbearing among HIV-affected couples, studies show many people living with HIV want to have children (Nattabi et al. Citation2009), and advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART) as treatment and prevention can eliminate sexual HIV transmission (Matthews et al. Citation2018). Studies find that access to ART increases reproductive desires among people living with HIV (Yan, Du, and Ji Citation2021).

Stigma is a multifaceted concept experienced at multiple levels. Turan et al. describe four dimensions of individual-level stigma, which may impact health behaviours and outcomes (2017). Enacted HIV stigma refers to actual experiences of discrimination and prejudice by others because of one’s HIV status. Perceived HIV stigma refers to an individual’s perceptions of community attitudes towards people living with HIV, and anticipated stigma refers to an individual’s expectation of negative treatment based on HIV status. Internalised stigma refers to an individual’s acceptance of the negative attitudes and beliefs about people living with HIV, or another stigmatised health condition (Turan et al. Citation2017). Intersecting forms of stigma may have multiplicative effects, resulting in complex health impacts. In this sample of serodifferent couples in Uganda, individuals and couples affected by HIV- and infertility-related stigma face social, emotional and physical health challenges that may impact their health and behaviour (Turan et al. Citation2019).

Research to explore the compounding effects of infertility and HIV stigma on mental health, partnership dynamics, HIV prevention and care-seeking among couples has been limited, yet understanding this intersection is a crucial step to providing high-quality care to members of this population. In this paper, we present a secondary analysis of qualitative data collected from HIV-negative women and a subset of their partners who participated in a safer conception intervention in rural, southwestern Uganda (Matthews et al. Citation2020). The intervention provided safer conception care, inclusive of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), to HIV-negative women with personal or partner plans for pregnancy in the next year. Women reported a partner living with HIV or otherwise felt at risk for acquiring HIV and were followed for up to 9 months. Perhaps because of the focus on conception, the qualitative exit interviews with a subset of women and their partners showed multiple forms of stigma experienced by individuals trying to conceive in serodifferent partnerships. We explore how infertility experiences among individuals and couples experiencing HIV-related stigma, in the context of local cultural and gender norms, may contribute to decreased adherence to safer conception strategies and subsequent increased HIV transmission risk.

Materials and methods

Design

This study was a part of a larger mixed-methods study conducted in a rural referral hospital in southwestern Uganda, with 131 women who were over the age of 18; HIV-negative (based on onsite testing); likely to be fertile (based on reproductive history, Bunting and Boivin Citation2010); not pregnant (based on urine b-HCG testing); reported personal or partner pregnancy plans within the next year; partnered with a man living with HIV or otherwise felt at risk for acquiring HIV; lived within 60 kilometres of the referral hospital; and were able to attend quarterly clinic visits during a 9-month follow-up period. Eligible participants were fluent in English or the local language, Runyankole, and able to consent.

Participants attended quarterly study visits, which included HIV and pregnancy testing, questionnaire completion, and safer conception and adherence counselling sessions. Women could initiate PrEP (TDF/FTC) at any time during the 9-month study follow-up. Prior to February 2019, women with an incident pregnancy exited the study prior to the end of the maximum follow-up period; after February 2019, women were followed through to the end of pregnancy given concerns regarding the ethics of PrEP discontinuation during pregnancy. Female participants attended safer conception counselling sessions developed for HIV-negative women who wanted to conceive with a partner with HIV, offered at time of enrolment and at quarterly intervals during the study. Counselling included messages about encouraging partners to test and disclose their serostatus, initiate ART if eligible, delay condomless sex until viral suppression had been achieved or until the partner used ART for 6 months, use contraception to delay pregnancies until safer conception strategies had been implemented, limit condomless sex to peak fertility and/or consider donor sperm, adoption or sperm washing as alternatives to conceiving. PrEP education and adherence counselling were offered to the women during individual support sessions at the time of enrolment and thereafter at quarterly visits.

Forty-five women were invited to participate in exit in-depth interviews (IDIs) to explore barriers and promoters of safer conception strategies and PrEP use. The women were given the option to invite their male partners who were fluent in English or Runyankole and able to consent to participate in separate IDIs. The interview guide was not designed to explore infertility experiences, but as participants discussed their experiences, themes of infertility were identified.

Data collection

Demographic data, depression (Hopkins Symptom Checklist (Parloff, Kelman, and Frank Citation1954)) and number of prior pregnancies, live births and living children were collected at enrolment ( and ).

Table 1. Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of HIV-negative women who completed exit interviews.

Table 2. Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of male partners who completed in-depth interviews.

Participants who completed IDIs were selected from three samples with about 15 women per group: (1) women who chose not to initiate PrEP; (2) women who initiated PrEP and took less than 80% of their doses (measured by electronic pill cap); and (3) women who initiated PrEP and took 80% or more of their doses.

Interview guides were informed by a conceptual framework for periconception risk reduction and adherence (van der Straten et al. Citation2014; Crankshaw et al. Citation2012). The guide explored topics such as PrEP dosing behaviour and barriers to and promoters of safer conception strategy adherence over time. Male partners were invited to participate in a separate interview which covered their experiences with safer conception strategies.

Interviews were conducted in either English or Runyanokole, as preferred by the participant. Themes of challenges with conceiving were developed from interviews with both female participants and their male partners.

Data analysis

Interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and translated into English as necessary. Transcripts were reviewed by four team members and evaluated. A codebook was generated through inductive analysis and organised into themes. Once the codebook had been finalised, 14% of interviews were double-coded yielding a kappa statistic of 0.829. Transcripts were then coded by two team members (MO and MCP), analysed using inductive content analysis and organised with NVIVO 12 Plus.

Ethics

Participants provided voluntary, written informed consent at study enrolment. Ethics approvals were obtained from the Institutional Review Committee of Mbarara University of Science and Technology (Mbarara, Uganda); the Institutional Review Board of University of Alabama at Birmingham (Birmingham, AL, USA); and the Research Ethics Board of Simon Fraser University (Burnaby, Canada). Study clearance was received from the Uganda National Counselling for Science and Technology and the Research Secretariat in the Office of the President.

Results

Participant characteristics

Thirty-seven women () and seven male partners () participated in an interview. While all participants contributed to findings through discussion of HIV- and reproduction-related stigma, 13 (35%) female in-depth interview participants and three (43%) male partners specifically described challenges with conceiving, experiences with miscarriage and unfulfilled reproductive goals. All participants described how HIV- and reproduction-related stigma impacted their own identities, communication within their partnerships and their use of safer conception strategies.

Similar narratives were found across the 44 total interviews, including among those who experienced pregnancy during the study follow-up. The additive pressures of cultural and gender norms, HIV-serodifferent relationships and personal reproductive desires often strained partnerships. Some couples overcame the challenges, identifying safer conception counselling and PrEP use as promoters of communication with in their relationships. Others discussed their growing frustration with safer conception strategies and their misperceptions about the effects of PrEP, despite the support they described receiving from the study staff.

The following cross-cutting themes were developed: (1) partnership mistrust and blame arise from internalised, anticipated and enacted HIV- and infertility-related stigma, contributing to gender-based violence, partnership dissolution and the pursuit of new partners; (2) cultural and gender norms pressure both men and women to conceive and maintain partnerships, which is complicated by the stigma shown towards serodifferent couples; (3) frustrations with delayed conception and low partner participation in safer conception strategies may result in the decreased use of these methods of HIV prevention; (4) health care provider support may promote continued hope for conception and help overcome stigma. Participants have been assigned pseudonyms to protect confidentiality. Additional barriers and promoters of PrEP use among this study population are described elsewhere (Atukunda et al. Citation2021).

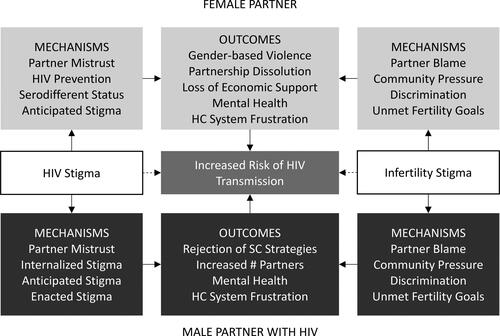

We adapted Earnshaw’s model of HIV stigma mechanisms (Earnshaw and Chaudoir Citation2009) () to reflect the intersectional HIV- and infertility-related stigma that may be experienced by some serodifferent couples, especially in the cultural context of Uganda, where expectations to bear children drive fertility desires (Dierickx et al. Citation2018; Beyeza-Kashesy et al. Citation2010; Heys et al. Citation2012; Mindry et al. Citation2017) and HIV prevalence is high (UNAIDS Citation2020).

Partnership mistrust and blame arise from internalised, anticipated and enacted HIV- and infertility-related stigma, contributing to gender-based violence, partnership dissolution and the pursuit of new partners

Participants sought identifiable reasons for their unmet reproductive goals, including biomedical (e.g. HIV, medication) or spiritual reasons (e.g. God’s will or curses cast by in-laws). Without a clinical explanation for infertility, participants struggled with internalised stigma, wondering if their infertility experiences were their fault and worried about the role of HIV in their experiences. As a result, partnership conflicts emerged from this infertility blame among serodifferent couples, driven by internalised and experienced stigma. Socio-cultural pressures to conceive and misunderstandings about the causes of infertility contributed to some couples questioning the legitimacy or sustainability of their serodifferent relationships and their ability to conceive children within them. Couples discussed their desire to have children to maintain their legacy, with some intentionally choosing their partners because they were HIV-negative. Below, couples described their experiences.

I am the one that needs the child the most because I am tired of him harassing me because I have refused to give him a child…He mistreats me because of failure to conceive. He abuses me that I do not want to give him a child intentionally because for me I already have my own children and [he thinks] I do not want him to also have children of his own. – Rose (female, age 29, HIV-negative)

At times I tell her that she is the one that never wanted to get me a child quickly in the first place, and now that she wants one it has refused to come… Maybe HIV is the reason why I have failed to impregnate my wife. I got very sick in 2016 and I got worried that I was going to die without a child so when I met her, I told her that all I wanted was having a child… I am happy that my wife is HIV-negative, and this is what is motivating me to have a child with her… In case she fails to give me a child completely I will leave her and marry another one. – John (Rose’s partner, male, age 35, living with HIV)

The members of another couple said,

Personally, I thought my wife was the one with a problem. I thought that maybe she was not able to have children. I also got worried that maybe I am the one that is not able to have children… Do you know how it feels when the rest of your friends have children and you have not yet had one, yet you are a man who is capable of looking after a family? It really makes you feel bad. – Moses (Grace’s partner, male, age 32, living with HIV)

[My husband] said, ‘Do you know that your friend told me that I am wasting time with you because you are not going to give birth… the pregnancies that you talk about are all lies’. I felt bad, that is what made him stop trying to have a child… When I went through this, I thought of stopping everything because I had a negative attitude towards [my husband]. If he would believe such lies about me… I am struggling, I have not refused to stay with him knowing he is sick [living with HIV] but for him, he trusted those lies. That is the time when we were going to separate. – Grace (female, age 27, HIV-negative)

Both men and women feared their partner might leave them when reproductive goals remained unmet.

If you marry a wife and you don’t have a child with her, she stays insecure thinking that you are not serious, but when she gets a child for you then she feels secure that the relationship is serious because she knows that you cannot leave her since you have a child together. – Richard (Mary’s partner, male, age 37, living with HIV)

Women shared anecdotes of their husbands picking fights and physically abusing them because they had not conceived. The following quote comes from a woman who was abused by her husband when she did not become pregnant according to his expectations.

He is harassing me that I have refused to get pregnant. Whenever he comes back, he asks me why he is not noticing any pregnancy signs and when I tell him that I don’t know; then he starts a fight. I am not on any family planning method, but the problem is that he does not come home during the times when I am in my peak fertility days. Even when he comes back when I am in my peak fertility days, he is tired, takes a bath and sleeps, so I wonder how he expects me to get pregnant. I have tried to explain to him, but he does not seem to understand; all he likes is quarrelling and fighting, telling me that I do not want to give him another child. Even the way he has been giving me money has changed; he now leaves money for his child alone and not for me because according to him, he thinks that I have refused to give him a child. So, he is punishing me; he thinks that I want to leave him and that I have another man… Right now, our family is not okay. I know all that is happening because I have failed to give him a child. – Sarah (female, age 26, HIV-negative)

Sarah explained how their serodifferent relationship made her husband feel insecure in the partnership and having a child might offer security. Another woman questioned the sustainability of her serodifferent partnership when she did not become pregnant. These quotes show the complicated intersection of HIV and childlessness in HIV-affected partnerships, as both men and women struggle with their serodifferent status, exacerbated by difficulties of conceiving.

It is because he has HIV and I don’t have it, so he thinks I want to leave him. He does not trust me… because I have not produced for him many children. – Sarah (female, age 26, HIV-negative)

What if the pregnancy refuses to come, can I still stay with this man and can I stay taking this medicine [PrEP] when I am not sick and not sure of my partner’s status? – Florence (female, age 40, HIV-negative)

Cultural and gender norms put pressure on men and women to conceive and maintain partnerships, which is complicated by stigma towards serodifferent couples

Cultural, community and family pressures to have children exacerbate the strain on relationships. Participants describe how family members pressured them to conceive to meet cultural expectations, adding to the strain participants faced as they navigated stigmatised serodifferent partnerships and the stigma directed towards people living with HIV having children.

His people are putting pressure on him to have a child since all his brothers have children. – Betty (female, age 29, HIV-negative, pregnant)

Gender dynamics skew reproductive decision-making power, and many participants discussed accusations of secretly using or removing family planning methods as a means of women retaining some autonomy over their reproductive goals. One participant described how she had been treated by her husband’s family when she had not conceived as expected.

His mother was bringing chaos in our marriage… [she says] that I must be using family planning, but I told her that I am not … she had even started convincing him to have another wife. – Jane (female, age 37, HIV-negative)

The following quote from a male partner describes how he sought to retain much power over the couple’s reproductive decision-making, and he did not trust his wife without a child.

As you know women can never be relied on. I cannot be sure that I will stay with her [if we don’t have a child together]. I know that maybe she will also leave me… She was on family planning, and I asked her to remove it so that she can give me a child, and she agreed to do that… When I met her, I asked her that I want a child with her because it is not good to have a wife with whom you do not have a child, so she agreed to give me one… and she became pregnant. – Fred (Agnes’s partner, male, age 36, HIV status unknown)

While cultural and gender norms put pressure on both men and women to conceive and maintain partnerships, some participants indicated they desired pregnancy later in their relationship. They explained their interest in the study was primarily to initiate PrEP, access to which is limited in the public sector in Uganda. Their individual reproductive goals evolved as they felt reassured by PrEP’s protection from HIV transmission within their serodifferent partnerships.

I mainly joined the study so that I stay healthy and then by the time I choose to give birth I may give birth to a healthy child… When I learnt that these drugs protect you, I also became more motivated to have a child because I know that the child will have no problem. But it is just that I have failed to conceive… I have not yet understood why I am not conceiving. – Harriet (female, age 31, HIV-negative)

Frustrations with delayed conception and low partner participation in safer conception strategies result in decreased use of these methods for HIV prevention

Frustration with unmet reproductive goals was often expressed as mistrust in the effectiveness of safer conception strategies. Some participants abandoned safer conception strategies when they felt the strategies were not agreeable with their partners, impeded them from conceiving or if they lived apart from their partner for a long time.

She told me about the timed condomless sex, and I had also learned about it from TASO [local AIDS service organisation, The AIDS Support Organisation]. We tried it but nothing happened, and I got tired of counting those days, so I stopped, but we are still trying though not on the days that the counsellor told her. She told me about using a condom, but I refused that. I cannot use a condom with my own wife, that can never happen. Maybe if I am sleeping with another woman but for my wife, I can never do such a thing… We tried all the methods that you told us; things did not work out. – John (Rose’s partner, male, age 35, living with HIV)

Even if he is the one that makes the decision to have children, he does not want to cooperate with me. I tell him that we should count, and we have sex during my peak fertility days, he does not want to try that, yet he is ever complaining that I do not want to give him a child. So now I don’t know what to do. – Sarah (female, age 26, HIV-negative)

Many participants described hesitation in taking daily PrEP when they considered themselves healthy. Their perceptions of PrEP’s effectiveness, side effects and impact on fertility were also skewed by their shared or individual desire to have an HIV-negative child, especially in fully disclosed partnerships.

We have spent three years [trying to conceive] … She knew that when she started [PrEP] she would have gotten pregnant by now, but she has not yet conceived. When she comes this side, she asks me, ‘They told me that when I keep taking these drugs for some months, I will have gotten pregnant, but I am not getting pregnant’. I usually tell her, ‘No, keep on taking your drugs. The pregnancy will come eventually’. … We have been trying to have a child, nothing has changed, we still want a child. – Moses (Grace’s partner, male, age 32, living with HIV)

Health care provider support may promote continued hope for conception and help overcome stigma

As illustrated above, while participants were frustrated by their unmet reproductive goals and their confusion about PrEP’s potential role in their fertility, many participants described the support of study staff as a promoter of continued hope in conceiving.

In the past I used to wonder if I will get pregnant again. [The study] taught me, and I followed what they taught me. I see that what you taught me has helped me even though I am not yet pregnant, but I now have hope that soon I will get pregnant. – Helen (female, age 19, HIV-negative)

Before I heard about this [study] I knew that giving birth had ended. Because I was not seeing any hope in future. I would ask myself, ‘My husband is sick, with a condom you cannot get pregnant’. I felt hopeless… but when I joined the study and was taught, I felt very hopeful and saw that my chances were still there, but otherwise I had given up… I have learned that even though a man is sick I can still get pregnant, and we give birth to a child… it has helped me remain in my family without leaving my husband or even my children. It has also given me hope that I will give birth to another child who is healthy even though my husband is sick. I have learned that, but there people out there who are still in the dark. But I am grateful for this study that I have been able to learn this. – Irene (female, age 32, HIV-negative)

Frustrations with safer conception strategies did not cause participants to be averse to future engagement in care. Despite not conceiving, difficulties with partnerships and the potential for increased HIV transmission driven by the pursuit of new partners, most participants considered themselves happy with the safer conception programme and the counselling they received.

Many participants discussed the benefits of the programme’s counselling, including supported serostatus disclosure, increased partnership communication and empowerment in HIV prevention.

[The programme] taught us everything and we followed it. We learned that we can live a healthy life together with my husband because of the services you gave us, and we learned to love ourselves. – Ruth (female, age 36, HIV-negative)

Because of the counselling I feel relaxed about my [HIV] status. I no longer worry a lot about my status. – Fred (Agnes’s partner, male, age 36, HIV status unknown)

Before I joined the study we used not to talk. I had separated with him, but now when I joined the study, I know that he is a person like others, and we normally discuss about his status and about having children. – Lydia (female, age 31, HIV-negative)

These findings indicate that safer conception counselling is beneficial to these serodifferent relationships.

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of qualitative data from a cohort of HIV-negative women and a subset of their male partners accessing safer conception care in rural Uganda, participants described intersecting forms of stigma linked to living with HIV, partnering with someone living with HIV, desiring a child while in a serodifferent partnership, and having unmet reproductive needs. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore these interconnected experiences from the perspective of both women and men in the context of HIV prevention. Our findings suggest that HIV and infertility-related stigma intersect in HIV-affected partnerships, and may contribute to mental health struggles, complicated relationships and abandonment of HIV prevention strategies such as timing condomless sex to peak fertility and PrEP. Couples may increase the likelihood of sexual transmission of HIV through the abandonment of risk-reduction strategies and the pursuit of new partners as pressures from family and community urge individuals to meet reproductive goals.

Numerous studies in sub-Saharan Africa examine HIV- and infertility-related stigma separately. Many find that women bear a disproportionate burden of blame for difficulties conceiving (Fledderjohann Citation2012; Dhont et al. Citation2011). As in many other studies, participants reported gender-based violence in relationships affected by unmet reproductive goals (Dierickx et al. Citation2018; Dhont et al. Citation2011; Anokye et al. Citation2017); this observation among couples affected by both unmet reproductive goals and HIV is a unique contribution to the literature. Studies have also found psychological effects like low self-esteem, distress and depression, and social effects like exclusion, verbal and physical abuse, and marriage breakdown affecting couples experiencing infertility in Ghana (Anokye et al. Citation2017) and South Africa (Dyer, Lombard, and Van der Spuy Citation2009; Dyer et al. Citation2004).

Our study explores an under-researched set of issues: separate interviews with partners reveal their individual and dyadic perspectives. Men and women both experienced internalised stigma related to infertility in the form of feelings of guilt and shame, and enacted stigma such as the pressure to bear children from friends and family (Dyer, Lombard, and Van der Spuy Citation2009; Dhont et al. Citation2010; Dyer et al. Citation2004). Both male and female participants’ experiences of childlessness are crucial to understanding the socio-cultural intersection between HIV and infertility, especially in serodifferent partnerships. The perspectives of both partners may inform avenues for stigma reduction and improved gender equity through individual and couple-based counselling and education and in other ways.

While the intersection between HIV and infertility-related stigma remains under-researched, the SARS-CoV2 pandemic has highlighted the salience of infertility stigma, as some forms of vaccine hesitancy are driven by fears of fertility impacts (Diaz et al. Citation2021). Discussion about fertility’s interactions with infectious diseases and subsequent forms of stigma are important for public health, as such intersections may drive the utilisation of prevention strategies such as safer conception strategies and vaccinations.

Our data signal the importance of broadly addressing sexual health and relationship dynamics among serodifferent couples. Alongside counselling messages about STI and HIV prevention, couples should receive counselling on partnership communication, shared decision-making, gender-based violence prevention, and causes and treatment options for infertility. Reproductive health interventions that consider the co-experience of multiple health-related forms of stigma are needed within this context to reduce health disparities among couples affected by HIV.

Limitations

This study has its limitations. Importantly, it was not designed to examine the intersecting effects of HIV- and infertility-related stigma. The interview guide was focused on relationship dynamics, HIV prevention, safer conception strategies and PrEP use, and did not include questions specifically about infertility. Participants’ fertility experiences became clear during the study, although limited in depth. As infertility is a clinical diagnosis, what we refer to may perhaps be more aptly described as unmet reproductive goals.

Additionally, the role of nondisclosure in the dynamics of serodifferent relationships was not further explored as many participants had mutually disclosed; additional studies and analyses could examine these associations with more depth. The study design may have increased pressure to conceive felt by participants during the study follow-up period of 9 months, to ensure they received quality care during and after their pregnancy.

Our study likely under-represents those experiencing fertility challenges because we recruited participants who were already accessing care and likely to fertile based on a validated screening tool (Bunting and Boivin Citation2010). The primary study was funded to provide an HIV prevention intervention for HIV-negative women owing to the high HIV incidence in this population, which then impacts mother to child transmission.

In much HIV programmatic work, women are prioritised as a ‘key population’ given their high exposure to and rates of HIV. In future work, we hope to explore these themes with a more diverse population representing diverse gender and HIV experiences. A more detailed interview examining infertility among HIV-affected couples may provide different or more in-depth insights into the experiences of people who struggle to conceive while in a safer conception programme.

Conclusion

This study found that men and women in HIV-affected partnerships experience unmet reproductive goals, and stigma related to HIV and childlessness are exacerbated by partnership mistrust, community pressures and lack of access to counselling and care for infertility experiences. Future research should examine the intersecting forms of stigma affecting HIV-serodifferent couples desiring pregnancy, including among women living with HIV, and future safer conception programmes should be designed to address the multiple and intersecting forms of stigma associated with HIV, serodifferent partnerships, childbearing within HIV-affected partnerships, and infertility, with screening and support for those experiencing gender-based violence. Future programmes should adapt counselling messages to engage with gender dynamics and relationships, promote shared decision-making in the couple, address PrEP and other safer conception strategies’ roles in fertility and conception, and provide medical and emotional support for serodifferent couples who experience delays in conception.

Data availability

The informed consent procedure for the study does not allow for us to make the qualitative data (collected from a small sample of men) publicly available. Data-access requests for elements of raw data may be sent to the UAB Center for Clinical and Translational Science via [email protected] The corresponding author may also be contacted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anokye, R., E. Acheampong, W. K. Mprah, J. O. Ope, and T. N. Barivure. 2017. “Psychosocial Effects of Infertility among Couples Attending St. Michael's Hospital, Jachie-Pramso in the Ashanti Region of Ghana.” BMC Research Notes 10 (1): 690.

- Atukunda, E. C., M. Owembabazi, M. C. Pratt, C. Psaros, W. Muyindike, P. Chitneni, M. B. Bwana, D. R. Bangsberg, J. E. Haberer, J. M. Marrazzo, et al. 2021. “A Qualitative Exploration to Understand High, Sustained Adherence to Daily Oral PrEP among HIV-Negative Women Planning for or with Pregnancy in Rural Southwestern Uganda.” Journal of the International AIDS Society. Manuscript under Review, October 22 2021, typescript.

- Beyeza-Kashesy, J., S. Neema, A. M. Ekstrom, F. Kaharuza, F. Mirembe, and A. Kulane. 2010. ““Not a Boy, Not a Child": A Qualitative Study on Young People's Views on Childbearing in Uganda.” African Journal of Reproductive Health 14 (1): 71–81.

- Brubaker, S. G., E. A. Bukusi, J. Odoyo, J. Achando, A. Okumu, and C. R. Cohen. 2011. “Pregnancy and HIV Transmission among HIV-Discordant Couples in a Clinical Trial in Kisumu, Kenya.” HIV Medicine 12 (5): 316–321.

- Bunting, L. and J. Boivin. 2010. “Development and Preliminary Validation of the Fertility Status Awareness Tool: Fertistat.” Human Reproduction 25 (7): 1722–1733.

- Crankshaw, T. L., L. T. Matthews, J. Giddy, A. Kaida, N. C. Ware, J. A. Smit, and D. R. Bangsberg. 2012. “A Conceptual Framework for Understanding HIV Risk Behavior in the Context of Supporting Fertility Goals among HIV-Serodiscordant Couples.” Reproductive Health Matters 20 (39 Suppl): 50–60.

- Davey, J. D., S. West, V. Umutoni, S. Taleghani, H. Klausner, E. Farley, R. Shah, S. Madni, S. Orewa, V. Kottamasu, et al. 2018. “A Systematic Review of the Current Status of Safer Conception Strategies for HIV Affected Heterosexual Couples in Sub-Saharan Africa.” AIDS & Behavior 22 (9): 2916–2946.

- Dhont, N., S. Luchters, W. Ombelet, J. Vyankandondera, A. Gasarabwe, J. van de Wijgert, and M. Temmerman. 2010. “Gender Differences and Factors Associated with Treatment-Seeking Behaviour for Infertility in Rwanda.” Human Reproduction 25 (8): 2024–2030.

- Dhont, N., J. van de Wijgert, G. Coene, A. Gasarabwe, and M. Temmerman. 2011. “'Mama and Papa Nothing': Living with Infertility among an Urban Population in Kigali, Rwanda.” Human Reproduction 26 (3): 623–629.

- Diaz, P., P. Reddy, R. Ramasahayam, M. Kuchakulla, and R. Ramasamy. 2021. “COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy Linked to Increased Internet Search Queries for Side Effects on Fertility Potential in the Initial Rollout Phase Following Emergency Use Authorization.” Andrologia 53 (9): e14156.

- Dierickx, S., L. Rahbari, C. Longman, F. Jaiteh, and G. Coene. 2018. “'I Am Always Crying on the Inside': A Qualitative Study on the Implications of Infertility on Women's Lives in Urban Gambia.” Reproductive Health 15 (1): 151.

- Dyer, S., C. Lombard, and Z. Van der Spuy. 2009. “Psychological Distress among Men Suffering from Couple Infertility in South Africa: A Quantitative Assessment.” Human Reproduction 24 (11): 2821–2826.

- Dyer, S. J., N. Abrahams, N. E. Mokoena, and Z. M. van der Spuy. 2004. “‘You Are a Man Because You Have Children': Experiences, Reproductive Health Knowledge and Treatment-Seeking Behaviour among Men Suffering from Couple Infertility in South Africa.” Human Reproduction 19 (4): 960–967.

- Earnshaw, V. A. and S. R. Chaudoir. 2009. “From Conceptualizing to Measuring HIV Stigma: A Review of HIV Stigma Mechanism Measures.” AIDS & Behavior 13 (6): 1160–1177.

- Fledderjohann, J. J. 2012. “'Zero Is Not Good for Me': Implications of Infertility in Ghana.” Human Reproduction 27 (5): 1383–1390.

- Grosskurth, H., R. Gray, R. Hayes, D. Mabey, and M. Wawer. 2000. “Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases for HIV-1 Prevention: Understanding the Implications of the Mwanza and Rakai Trials.” The Lancet 355 (9219): 1981–1987.

- Grosskurth, H., F. Mosha, J. Todd, K. Senkoro, J. Newell, A. Klokke, J. Changalucha, B. West, P. Mayaud, and A. Gavyole. 1995. “A Community Trial of the Impact of Improved Sexually Transmitted Disease Treatment on the HIV Epidemic in Rural Tanzania: 2. Baseline Survey Results.” AIDS 9 (8): 927–934.

- Kudesia, R., M. Muyingo, N. Tran, M. Shah, I. Merkatz, and P. Klatsky. 2018. “Infertility in Uganda: A Missed Opportunity to Improve Reproductive Knowledge and Health.” Global Reproductive Health 3 (4): e24.

- Heys, J., G. Jhangri, T. Rubaale, and W. Kipp. 2012. “Infection with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus and Fertility Desires: Results from a Qualitative Study in Rural Uganda.” World Health & Population 13 (3): 5–17.

- Lubega, M., N. Nakyaanjo, S. Nansubuga, E. Hiire, G. Kigozi, G. Nakigozi, T. Lutalo, F. Nalugoda, D. Serwadda, R. Gray, et al. 2015. “Risk Denial and Socio-Economic Factors Related to High HIV Transmission in a Fishing Community in Rakai, Uganda: A Qualitative Study.” PLoS One 10 (8): e0132740.

- Mascarenhas, M. N., S. R. Flaxman, T. Boerma, S. Vanderpoel, and G. A. Stevens. 2012. “National, Regional, and Global Trends in Infertility Prevalence Since 1990: A Systematic Analysis of 277 Health Surveys.” PLoS Medicine 9 (12): e1001356.

- Matthews, L. T., J. Beyeza-Kashesya, I. Cooke, N. Davies, R. Heffron, A. Kaida, J. Kinuthia, O. Mmeje, A. E. Semprini, and S. Weber. 2018. “Consensus Statement: Supporting Safer Conception and Pregnancy for Men and Women Living with and Affected by HIV.” AIDS & Behavior 22 (6): 1713–1724.

- Matthews, L. T., M. B. Bwana, M. Owembabazi, P. Chitneni, J. E. Haberer, K. Bennett, K. E. H. Wirth, D. R. Bangsberg, and J. M. Marrazzo. 2020. “High Prep Uptake and Adherence among HIV-Exposed Ugandan Women with Personal or Partner Plans for Pregnancy in Uganda.” Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on HIV Treatment and Prevention Adherence (Adherence 2020 Virtual), November 2-3, 2020. Virtual.

- Mindry, D., R. K. Wanyenze, J. Beyeza-Kashesya, M. A. Woldetsadik, S. Finocchario-Kessler, K. Goggin, and G. Wagner. 2017. “Safer Conception for Couples Affected by HIV: Structural and Cultural Considerations in the Delivery of Safer Conception Care in Uganda.” AIDS & Behavior 21 (8): 2488–2496.

- Nattabi, B., J. Li, S. C. Thompson, C. G. Orach, and J. Earnest. 2009. “A Systematic Review of Factors Influencing Fertility Desires and Intentions Among People Living with HIV/AIDS: Implications for Policy and Service Delivery.” AIDS & Behavior 13 (5): 949–968.

- Parloff, M. B., H. C. Kelman, and J. D. Frank. 1954. “Comfort, Effectiveness, and Self-Awareness as Criteria of Improvement in Psychotherapy.” The American Journal of Psychiatry 111 (5): 343–352.

- The World Bank. 2019. “Fertility Rate, Total (Births Per Woman) – Uganda.” https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=UG

- Turan, B., A. M. Hatcher, S. D. Weiser, M. O. Johnson, W. S. Rice, and J. M. Turan. 2017. “Framing Mechanisms Linking HIV-Related Stigma, Adherence to Treatment, and Health Outcomes.” American Journal of Public Health 107 (6): 863–869.

- Turan, J. M., M. A. Elafros, C. H. Logie, S. Banik, B. Turan, K. B. Crockett, B. Pescosolido, and S. M. Murray. 2019. “Challenges and Opportunities in Examining and Addressing Intersectional Stigma and Health.” BMC Medicine 17 (1): 7.

- Twa-Twa, J., I. Nakanaabi, and D. Sekimpi. 1997. “Underlying Factors in Female Sexual Partner Instability in Kampala.” Health Transition Review 7 Suppl (7 Suppl): 83–88.

- UBOS (Uganda Bureau of Statistics) and ICF. 2018. Uganda Demographic Health Survey 2016. Kampala, Uganda: UBOS and ICF.

- UNAIDS. 2020. “Country Factsheets: Uganda 2020.” Accessed November 20, 2021. https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/uganda

- van der Straten, A., J. Stadler, E. Montgomery, M. Hartmann, B. Magazi, F. Mathebula, K. Schwartz, N. Laborde, and L. Soto-Torres. 2014. “Women's Experiences with Oral and Vaginal Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis: The VOICE-C Qualitative Study in Johannesburg, South Africa.” PLoS One 9 (2): e89118.

- Williamson, N. E., J. Liku, K. McLoughlin, I. K. Nyamongo, and F. Nakayima. 2006. “A Qualitative Study of Condom Use among Married Couples in Kampala, Uganda.” Reproductive Health Matters 14 (28): 89–98.

- Yan, X., J. Du, and G. Ji. 2021. “Prevalence and Factors Associated with Fertility Desire Among People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” PLoS One 16 (3): e0248872.